Abstract

This case study analyzes the academic emotions generated in a STEAM educational project developed in the controversial heritage of the Río Tinto and its surroundings. Twenty-five secondary education students participated in a didactic sequence that combined programming and the use of sensors for physicochemical data collection with inquiry- and modeling-based methodologies to address socio-scientific issues. Data were collected through open-ended questionnaires and field notebooks, allowing for an analysis of the emotions expressed at different stages of the project. The results show that epistemic emotions, such as curiosity and surprise, were predominant, highlighting the positive impact of experimental learning in this educational approach. Achievement emotions, such as pride and enjoyment, were linked to overcoming technological challenges, while thematic emotions, such as admiration and disgust, emerged from the heritage context, fostering critical reflection on environmental and historical issues. Negative emotions, such as frustration and anxiety, were also identified, mainly related to the technical difficulties and organizational challenges in group work. It is concluded that the proposed didactic sequence, by integrating the STEAM approach within a heritage context, mobilizes the epistemic emotions that were key in fostering analytical thinking and scientific exploration, while thematic emotions strengthened students’ connection with environmental and historical issues.

1. Introduction

The role of emotions is crucial in learning development (Lincoln & Kearney, 2019; Mellado et al., 2014; Tyng et al., 2017). In addition to improving mental health and well-being in classrooms, managing emotions enhances attention, sparks curiosity, increases motivation, fosters a positive classroom climate, and strengthens other variables that directly influence learning capacity (Sáenz-López Buñuel, 2020). Thus, education requires emotions, and little can be built among individuals insensitive to them (Santacana & Martínez, 2018). However, despite their importance, the emotional dimension has long been one of the most neglected aspects of educational reforms, which often ignore or minimize this fundamental component of teaching (Hargreaves, 1998). Even today, greater emphasis is placed on students’ cognitive learning, often overlooking the impact of their emotions in educational settings (Liang et al., 2021).

Many studies focus on determining the presence of positive and negative emotions, and tools such as the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) (Gil-Madrona et al., 2019) are commonly used in this context, yet classifying emotions solely based on their valence provides limited information (Pérez-Bueno et al., 2024). According to Pekrun (2006), academic emotions are a key factor influencing learning. Research findings show a strong connection between these emotions and students’ learning outcomes and achievements (Davis & Bellocchi, 2018; Li et al., 2020; Pekrun & Linnenbrink-Garcia, 2014; Postareff et al., 2017; Schutz & Lanehart, 2002; Wang & Hsu, 2023), although their causality has not been widely studied (Tan et al., 2021).

Regarding science education, attitudinal, affective, and emotional aspects are considered decisive, as they can significantly influence students’ career aspirations in scientific fields (Lehtamo et al., 2018; Mellado et al., 2014). Inquiry- and modeling-based science education methodologies propose activity sequences structured in phases that foster student engagement with school science (Jiménez-Liso et al., 2022), promoting meaningful learning by triggering epistemic emotions, such as curiosity and surprise (Jiménez-Liso et al., 2021), and facilitating students’ intellectual and emotional involvement in problem-solving (Retana-Alvarado et al., 2023).

In recent years, with the rise of STEAM (science, technology, engineering, arts, and mathematics) approaches in education, understanding and measuring emotions in technology-rich learning environments have been deemed crucial to fostering academic progress in various domains (Lajoie et al., 2020). Recent studies indicate that secondary students experience a significant decline in positive emotions and an increase in negative emotions toward STEAM subjects as they transition from primary to secondary education (Martínez-Borreguero et al., 2019). Therefore, identifying specific emotions and sensations that arise in the classroom allows educators to anticipate them, making students aware of these emotions so they do not become barriers (e.g., insecurity) or go unnoticed (e.g., satisfaction) (Jiménez-Liso et al., 2023).

Furthermore, context plays a crucial role in how emotions are experienced, expressed, perceived, and regulated (Greenaway et al., 2018). In recent years, the scientific literature has increasingly explored the relationship between emotions and heritage education, highlighting how heritage sites and artifacts can evoke strong emotional responses, making them highly motivating didactic resources that enhance the teaching–learning process (Palacios et al., 2023; Santacana & Martínez, 2018). Emotions play a fundamental role in all social phenomena and catalyze and sustain creative scientific work, fueling scientific and intellectual movements that drive scientific change (Parker & Hackett, 2012).

This study was conducted with secondary education (4º ESO) students in the Río Tinto region, a controversial heritage site located in Southwestern Spain, as a unique educational setting to analyze the academic emotions generated during the implementation of an interdisciplinary didactic sequence. This river, known for its red and acidic waters, is not only of great scientific interest but also connects students with their local natural and cultural heritage. Through a STEAM approach that integrates computational thinking as a problem-solving process, as required by the Spanish curriculum (Real Decreto 217/2022, 2022), and inquiry- and modeling-based methodologies recommended for engaging students in school science (Grabau & Ma, 2017), this study explores and classifies the emotions that emerged throughout the implemented didactic sequence.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Academic Emotions

An emotion is an affective experience that temporarily alters our mental and physical balance, potentially manifesting with intensity (Santacana & Martínez, 2018). Academic emotions are those related to either academic activities or outcomes, generated by learners after performing a controlled cognitive and evaluative assessment of learning scenarios (Pekrun, 2000; Pekrun et al., 2002). In other words, academic emotions encompass all emotional experiences that students feel in learning or teaching situations regarding any event, action, or circumstance occurring in an educational context (Pekrun, 2006). Emotional responses require a prior subjective appraisal of the stimulus, which explains why individuals react with different emotions to similar situations (Pérez-Bueno et al., 2024).

Pekrun and Linnenbrink-Garcia (2012) define academic emotions as influential factors in students’ engagement and academic performance, developing a classification based on the Control–Value Theory of Emotions (Pekrun, 2006). This theory posits that emotions in learning depend on the perceived level of control and the value attributed to the academic activity, which influences how students experience different emotions in the classroom.

From this perspective, academic emotions are categorized into four groups:

- Achievement emotions: Related to success or failure in academic tasks. For example, joy after receiving a good grade or frustration due to a poor result;

- Epistemic emotions: Associated with the acquisition and processing of knowledge. Examples include curiosity when learning something new or confusion when encountering contradictory information;

- Social emotions: Derived from interactions with others in academic settings, such as embarrassment when speaking in public or pride in a group presentation;

- Thematic emotions: Related to the specific content of a subject, such as interest in a particular topic or rejection toward certain material.

2.2. Emotions and STEAM

STEAM education has a myriad of definitions and various interpretations of the “A” (arts), with ongoing debate regarding its true implementation (Perignat & Katz-Buonincontro, 2019; Toma & García-Carmona, 2021). In this study, STEAM is understood as an educational methodology that has been increasingly adopted and consolidated in recent years. It promotes an integrative approach that encourages analytical, critical, creative, and scientific thinking through the development of projects or work involving technological elements.

Educational research and neuroscience evidence argue that there is an inherent connection between emotion and learning, which is essential for the STEAM approach (Steele & Ashworth, 2018). The analysis of emotions has significant potential to improve students’ experiences, foster personalized learning, and enhance satisfaction in learning environments, particularly in STEAM subjects (Anwar et al., 2023).

In this context, emotions play a key role in shaping attention, motivation, and learning strategies in technology-integrated STEAM environments. Studies such as those by Loderer et al. (2020) on technology-based learning environments (TBLEs) indicate that interaction with digital tools elicits a wide range of academic emotions, including enjoyment, curiosity, anxiety, frustration, confusion, and boredom. While anxiety and frustration can hinder learning if not properly managed, enjoyment and curiosity are associated with higher motivation and performance. Additionally, they are positively linked to perceptions of control and the value of tasks, fostering greater engagement and academic achievement (Astleitner & Leutner, 2014; Pekrun & Perry, 2014). However, the use of technology in classrooms must strike a balance between autonomy and guidance, as excessive freedom or overly rigid structures can lead to negative emotions, such as frustration or boredom (Goetz & Hall, 2014).

2.3. Socio-Scientific Issues Linked to Controversial Heritage as Emotional Precursors

Authors such as Beniermann et al. (2021) and Sadler et al. (2007) highlight the importance of working with contextualized topics through socio-scientific issues (SSI). Scientific concepts emerge from real-world problematic situations where they are applied and acquire meaning (Lupión-Cobos & García-Ruiz, 2024). These problems not only enrich the understanding of scientific content but also serve as an effective tool for developing more critical and engaged citizens. Furthermore, the use of SSI in science education has a significant positive effect on learning content, decision-making skills, and reasoning (Badeo & Duque, 2022), as well as improving students’ emotional competence and ethical values, including responsibility, honesty, empathy, and integrity (Gao et al., 2019).

Thus, teaching controversial topics—defined as those that elicit strong emotions and divide public opinion—becomes essential (Huddleston & Kerr, 2016). According to Estepa and Martín-Cáceres (2018), incorporating controversial heritage into educational processes is fundamental. These are heritage elements selected for their ability to provoke dilemmas, debates, or social conflicts (Arroyo-Mora et al., 2022; Sampedro-Martín et al., 2022). By studying local heritage elements from an interdisciplinary perspective, students enhance their observation and inquiry skills, addressing current socio-environmental issues from diverse knowledge perspectives (Trabajo & Cuenca, 2022). These elements act as dynamic sources of knowledge, fostering dialogue and challenging preconceived ideas, positioning heritage as a resource for working with emotions, and contributing to a more just and equitable society (Gómez-Hurtado & Cuenca, 2022).

Emotions play a crucial role in the connection between heritage appreciation and community recognition. Studies indicate that social emotions, related to affection and belonging, significantly influence how communities perceive and legitimize their heritage identity (Gómez Villar & Canessa Vicencio, 2019).

3. Objectives

This study aims to examine the academic emotions elicited by a STEAM-based educational intervention centered on a controversial heritage site, analyzed from different perspectives, including its ecosystem and geology (Campina-López et al., 2025b), its heritage dimension (Campina-López et al., 2025a), and its physicochemical characteristics through sensors (Campina-López et al., 2025c). Accordingly, the following objectives are proposed:

- Objective 1: Analyze the academic emotions expressed by students after engaging in the didactic sequence, identifying the methodological factors that triggered them;

- Objective 2: Examine the academic emotions associated with programming and the use of microcontroller boards and sensors during the learning sequence, identifying their underlying causes;

- Objective 3: Define the academic emotions experienced by students in relation to their work on controversial heritage, as well as determine the factors that led to their emergence.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Context and Participants

This qualitative study was conducted in the context of the Río Tinto, a controversial heritage site in Southwestern Spain, involving 25 secondary education students from a public high school in Valverde del Camino (Huelva). The participants, aged 15 to 16, engaged in a STEAM-based educational project that combined classroom activities with a field trip to the Río Tinto and its surroundings. Prior to the intervention, students’ families or legal guardians were informed about the study and provided informed consent. The data were collected and processed anonymously and confidentially, in accordance with the ethical principles of educational research within the institutional framework.

4.2. Research Design

This study follows a qualitative case study design that analyzes, codes, and categorizes students’ responses in relation to the emotions expressed and their causes within the framework of a STEAM-based educational intervention contextualized in controversial heritage. It adopts a descriptive and interpretative approach, based on qualitative sources, such as open-ended questionnaires and field notebooks, to understand the emotional dimension of learning in a specific and contextualized experience. The study was part of a broader interdisciplinary project implemented in a secondary school, combining classroom activities with fieldwork and structured around inquiry, modeling, and the use of sensors. While this article focuses on students’ emotional responses, the complete educational sequence is described in detail in Campina-López et al. (2025a, 2025b, 2025c).

After defining the study’s objectives, a literature review was conducted on academic emotions (Loderer et al., 2020; Mellado et al., 2014; Pekrun et al., 2002; Pérez-Bueno et al., 2024) and their impact in educational contexts, particularly in STEAM learning environments.

According to Pekrun et al. (2002), curiosity is a fundamental epistemic emotion that enhances intrinsic motivation and experimental learning. Meanwhile, admiration is linked to the emotional impact of heritage sites, highlighting their ability to inspire respect and critical reflection (Santacana & Martínez, 2018). Pride, in turn, is classified as an achievement emotion, associated with success in academic tasks and overcoming technological challenges (Pekrun & Linnenbrink-Garcia, 2012). These three emotions broaden the scope of emotional analysis by addressing specific experiences within STEAM and heritage contexts.

4.3. First-Order Instruments

Based on this theoretical framework, two first-order instruments were designed for data collection:

- Questionnaire: Included 13 academic emotions, selected based on the studies of Pekrun and Linnenbrink-Garcia (2014) and Pérez-Bueno et al. (2024), who analyzed the impact of emotions on learning. Most of the emotions in this study, such as anxiety, curiosity, enjoyment, frustration, pride, surprise, and shame, align with these previous works. Additionally, some terminological adjustments were made, replacing rejection with disgust and interest with curiosity. The questionnaire underwent a validation process, obtaining a Fleiss’ kappa coefficient of 0.84, which, according to (Gwet, 2021), indicates substantial to almost perfect inter-rater reliability;

- Field Notebooks: During the field trip to the Río Tinto, students documented their emotions related to the activities they engaged in, such as group dynamics, interactions with the environment, and challenges related to technology use.

4.4. Second-Order Instruments

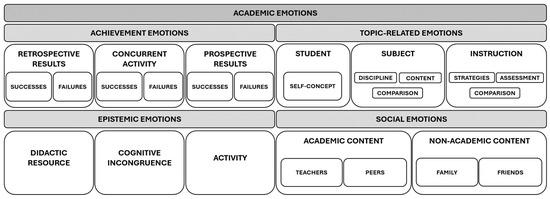

Following the work of Pérez-Bueno et al. (2024), Figure 1, which presents the hierarchical organization of the academic approaches, was used as a reference to categorize the emotions expressed by students along with their causes. To complement this analysis, Table 1 was developed based on the classification of academic emotions proposed by Pekrun and Linnenbrink-Garcia (2012). This table provides a detailed definition that enhances understanding and integrates with the information in Figure 1. These tools were essential in guiding the analysis, as they allowed for the classification of emotions into four main categories: achievement, epistemic, thematic, and social emotions. This categorization facilitated the interpretation of students’ affective experiences, providing a structured framework to analyze the emotional impact of the educational intervention.

Figure 1.

Hierarchical organization of academic approaches for grouping experienced emotions (Adapted from Pérez-Bueno et al., 2024).

Table 1.

Categorization of academic emotions according to Pekrun and Linnenbrink-Garcia (2012).

The emotions were coded based on the specific activity in which they emerged and their relationship with learning, using a deductive coding approach. This process relied on the open-ended responses provided by students in both the questionnaires and the field notebooks, which were interpreted in light of the academic emotions framework. For example, as shown in Table 1, curiosity was mostly classified as an epistemic emotion, as it was often linked to the discovery of patterns in the collected data. Pride was mostly coded as an achievement emotion, due to the satisfaction expressed after successfully completing a task. Surprise was typically identified as a thematic emotion, as it was related to the study content. Sympathy was generally categorized as a social emotion, given its frequent connection with peer interactions. The frequency of each academic emotion category was then calculated to identify the general patterns in the students’ affective responses across the different phases of the educational sequence.

To conduct the qualitative analysis, MAXQDA software was used, following these stages:

- Initial coding: The responses collected from the questionnaire and field notebooks were classified into the four categories of academic emotions using the previously mentioned second-order instruments;

- Data triangulation: Categorizations were unified, and the emotions recorded in the questionnaires and field notebooks were compared to identify consistent emotional patterns and detect possible discrepancies;

- Pattern and relationship analysis: Patterns in the expressed emotions were identified, along with their relationship to specific project activities, such as sensor programming, group dynamics, and interaction with controversial heritage.

The coding process was carried out in two rounds, with an interval of two months between them, to ensure rigor and consistency.

5. Results and Discussion

The results are organized according to the study’s objectives, aiming to better understand the emotions experienced by students. Their reactions to the didactic sequence, the use of technological devices, and the interaction with the controversial heritage were explored.

5.1. Characterization of Emotions Expressed in Relation to the Didactic Sequence

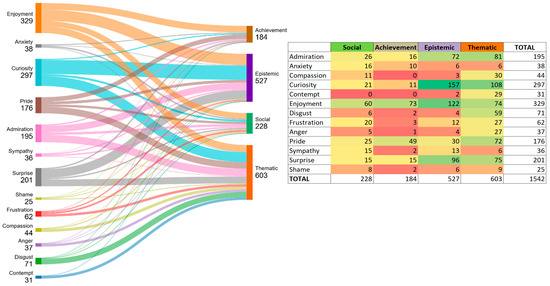

The implementation of the STEAM-based didactic sequence, contextualized in a controversial heritage setting, generated a wide variety of emotions among the students. As shown in Figure 2, epistemic and thematic emotions predominated, together accounting for over 70% of the total mentions (527 and 603, respectively). Although less frequent, achievement (184 mentions) and social emotions (228 mentions) also played a significant role, highlighting the collaborative work and the impact of the sequence on student motivation. In line with the findings of Pérez-Bueno et al. (2024), the results indicate that emotions such as interest (curiosity) and frustration (disgust) are generally thematic, while satisfaction (enjoyment) is typically categorized as an achievement emotion. In this study, compassion, sympathy, and shame were classified as social academic emotions, whereas enthusiasm was mainly identified as an epistemic emotion. The following section analyzes the main trends observed in each category, as well as the factors that led to these emotions:

Figure 2.

Distribution of frequencies of emotions and academic emotions manifested in the didactic sequence. Own elaboration.

- Achievement emotions (184 mentions, 12%) were less frequent but stood out in activities related to overcoming technical challenges. Emotions such as pride (49) and enjoyment (73) reflected students’ satisfaction in achieving significant milestones, such as programming sensors or creating final products like models. The results obtained show that achievement emotions, such as pride and enjoyment, not only reflect the overcoming of technical challenges but also enhance motivation, self-efficacy, and the acceptance of educational technologies (Stephan et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2024). These activities seemed to foster a sense of personal accomplishment and self-confidence, as illustrated by comments like “It was gratifying to see how our model perfectly represented what we learned in class” (student 17);

- Thematic emotions (603 mentions, 39%) revealed a strong connection between students and the project’s content. Admiration (81), enjoyment (74), and curiosity (108) were particularly prominent in the activities involving both the natural and cultural heritage of the Tinto River and its surroundings. Statements such as “It’s incredible how this place holds so much history and science at the same time” (student 4) or “Seeing that what we learned in class had real applications was exciting” (student 2) highlight how the STEAM sequence in this heritage setting effectively engaged students, helping them connect knowledge from different subject areas. It is also worth noting that negative thematic emotions, such as disgust (59) and anger (27), emerged from critical reflections on the environmental impact, historical inequalities, and social injustices related to the site. Comments like “It disgusts me to think that people allowed this river to become so polluted” (student 4) or “It’s unfair how the river’s resources benefited a few whiles harming many” (student 11) reflect students’ questioning and re-evaluation of past events, considering their consequences on the ecosystem and the local community.

- Epistemic emotions (527 mentions, 34%) were primarily represented by curiosity (157) and surprise (96), mainly triggered by inquiry-based and experimental activities. These findings highlight the importance of practical approaches, as illustrated by comments such as “The results surprised me; I didn’t expect them to be so precise” (student 5), “Each piece of data we obtained made me want to learn more” (student 20) or “I liked exploring both opposing perspectives” (student 8). These results align with Pekrun (2006), reinforcing the role of epistemic emotions in fostering analytical and creative thinking;

- Social emotions (228 mentions, 15%) underscored the relevance of group dynamics and collaboration. Positive emotions such as sympathy (15) and compassion (11) were commonly expressed during collaborative activities, such as model construction. Statements like “Working with my classmates helped me understand the topic better and enjoy it” (student 11) emphasize the positive impact of teamwork on learning. In line with Santacana and Martínez (2018), these responses suggest that the social context of learning facilitates shared reflection and collective knowledge construction. However, negative social emotions such as anxiety (16) and frustration (20) also emerged, mostly linked to group organization difficulties. Comments like “In my group, everyone did whatever they wanted whenever they wanted” (student 22) reveal challenges in coordination, indicating that structuring group activities effectively is crucial to minimizing conflict and optimizing collaboration.

These emotional patterns reflect the influence of specific pedagogical strategies. Inquiry and modeling fostered epistemic emotions like curiosity and surprise. Group work elicited social emotions, both positive and negative, depending on coordination. Achievement emotions were linked to goal-oriented tasks, such as programming sensors, while thematic emotions emerged from critical engagement with socio-environmental issues.

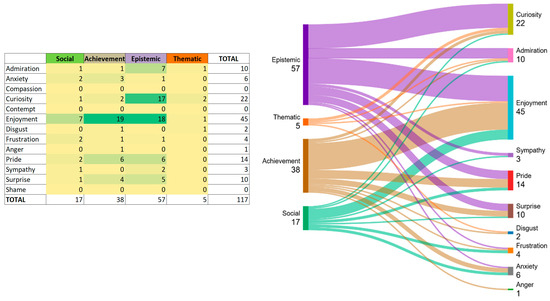

5.2. Characterization of Emotions Manifested in Relation to the Programming and Use of Electronic Controller Boards and Data Collection Devices

The programming and use of electronic controller boards and data collection devices within the STEAM project elicited a significant diversity of emotions among the students, as shown in Figure 3. Epistemic emotions accounted for 48.7% of the total, followed by achievement emotions (32.5%), social emotions (14.5%), and, to a lesser extent, thematic emotions (4.3%). These are described below:

Figure 3.

Distribution of frequency of emotions and academic emotions expressed regarding the use of technologies in the sequence.

- Achievement emotions (38 mentions, 32.5%) primarily included pride (6) and enjoyment (19) and were mainly linked to personal satisfaction in overcoming technical challenges, such as programming sensors and collecting data. Comments like “I thought I would never know how to program these devices, and I was surprised to see that I actually could” (student 5) or “In the end, I managed to get the sensor to collect data correctly, and it was very satisfying” (student 8) reflect the positive impact of these activities on students’ self-confidence. As highlighted by Martínez-Borreguero et al. (2019), success in practical tasks reinforces self-efficacy, strengthening interest in STEAM disciplines.

- Thematic emotions (5 mentions, 4.3%): These emotions were less representative compared to other categories. One example related to admiration included comments such as “the data reflect a serious environmental problem” (student 19). The lower prevalence of thematic emotions could be due to the fact that technological activities were more focused on developing practical skills and data analysis rather than on the conceptual content of heritage or natural sciences. This result differs from other studies where inquiry-based and model-based methodologies using technology, such as those by Jiménez-Liso et al. (2021), reported a greater connection between thematic emotions and inquiry activities, possibly due to a more balanced approach between practical skills and conceptual content in their instructional design. Authors such as Martínez-Borreguero et al. (2019) emphasize the need to design activities that integrate practical skills with an explicit focus on conceptual content to foster a stronger emotional connection and more meaningful learning;

- Epistemic emotions (57 mentions, 48.7%) were the most frequent during technological activities, with enjoyment (18), curiosity (17), admiration (7), and surprise (5) standing out. These emotions mainly emerged from the discovery and analysis of the data obtained through sensors. Comments such as “I was surprised by the precision of the data” (student 2) or “We wanted to keep testing to learn more about how the sensors worked” (student 8) highlight the positive impact of the experimental activities on students’ interest and motivation. The results align with other studies, such as those by Jiménez-Liso et al. (2021), which report that inquiry-based activities, supported by technologies such as modeling or practical tools, promote epistemic emotions by fostering curiosity and enhancing analytical understanding. These results are also consistent with Loderer et al. (2020), who indicate that, in technology-based learning environments, emotions such as curiosity/interest and enjoyment emerge when students perceive they have control over the technological task and consider it valuable. Additionally, these authors suggest that surprise is a key epistemic emotion, but its occurrence depends on the task structure and the level of expectation. According to Loderer et al. (2020), surprise arises when a student encounters unexpected or challenging information, which can generate curiosity and motivation to continue exploring. However, in our case, surprise had a lower representation (five), possibly because activities focused more on procedural aspects rather than the exploration of novel concepts or unexpected discoveries. This finding is also consistent with previous studies indicating that surprise is more common when learning involves unexpected findings, while in highly structured tasks, its occurrence tends to be lower;

- Social emotions (17 mentions, 14.5%) reflected group interactions during technological activities. Positive emotions such as enjoyment (seven) and sympathy (one) were common in collaborative dynamics, with comments like “It was fun working in a group to program the sensors” (student 6). According to Loderer et al. (2020), the social evaluation of the task and the technology used play important roles in generating emotions, as an environment that promotes teamwork and appreciation of group effort can enhance enjoyment and motivation, as recorded in this study. However, negative emotions such as frustration (two) and anxiety (two) were also present, mainly due to coordination problems and technical difficulties, as reflected in comments like “it was frustrating because we couldn’t agree on how to solve the errors” (student 9). This reinforces the need to better structure group dynamics and provide greater support during technological activities. These results align with those of Jiménez-Liso et al. (2021), who also highlight that group activities in technological environments can foster both collaboration and conflict, depending on the level of teacher guidance and task design.

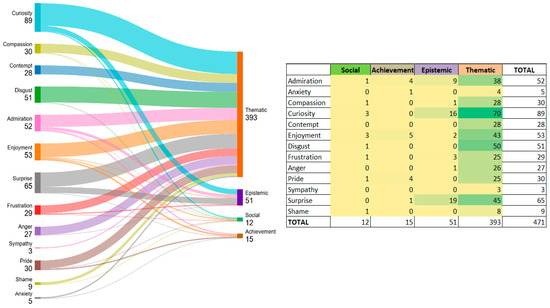

5.3. Characterization of Academic Emotions Expressed in Relation to the Controversial Heritage

Regarding the emotions associated with the heritage of the Río Tinto and its surroundings, a wide and balanced diversity of emotions was mobilized among students, as observed in Figure 4. After categorization, thematic emotions were predominant (83%), followed by epistemic emotions (11%), while achievement (3%) and social emotions (3%) were less frequent.

Figure 4.

Distribution of frequencies of emotions and academic emotions expressed in relation to controversial heritage.

- Achievement emotions (15 mentions, 3%) were minimally represented. However, emotions such as pride (four) and enjoyment (five) emerged in activities involving the overcoming of technical and argumentative challenges, such as debates on the cultural significance of heritage. Comments like “I felt proud of being able to argue my stance on the value of the river in the debate” (student 19) highlight how these activities fostered personal satisfaction and self-confidence. Nevertheless, the low frequency of these emotions suggests the need to design activities that more effectively enhance these positive experiences.

- Thematic emotions (393 mentions, 83%) were the most predominant in this category, with curiosity (70), enjoyment (43), and admiration (38) standing out. According to the results, these emotions reflect students’ interest in exploring the historical, cultural, and environmental impact of the Río Tinto. Comments like “I found it interesting to see how heritage reflects our history” (student 5) or “I discovered how English society significantly influenced our heritage and culture” (student 3) illustrate how heritage learning fosters cultural appreciation and content engagement. However, negative emotions such as disgust (50) and anger (26) also emerged, mainly from critical reflections on historical inequalities and environmental issues: “It disgusts me to think how the exploitation of resources near the river was allowed” (student 9), “It is not right that in the 21st century, we continue to justify these actions” (student 19) or “I felt disgust because it reflects a classist behaviour that should not occur.” (student 4) These emotions, although negative, highlight the ability of heritage to generate critical analysis, awareness, identity-related sentiments, and, ultimately, to provoke debate, dilemmas, and social conflict, aligning with authors such as Estepa and Martín-Cáceres (2018) and Gómez Villar and Canessa Vicencio (2019);

- Epistemic emotions (51 mentions, 11%) were mainly expressed as surprise (19) and curiosity (16). These emotions were linked to activities such as a scavenger hunt and a field trip, where students showed fascination over the processes and content related to heritage. Comments such as “I was surprised by how elements of local culture and heritage were transformed into an English-style town” (student 7) illustrate this. These epistemic emotions, particularly curiosity and surprise, support the development of analytical thinking and discovery, as previously highlighted by Pekrun (2006);

- Social emotions (12 mentions, 3%) were associated with group interactions. Despite the varied representation, social emotions were generally limited and scarce. Enjoyment (three) was linked to comments such as “It was interesting to hear my classmates’ perspectives on whether to conserve or restore the heritage” (student 24). These results suggest the need to improve heritage-related activities, as there may have been an unequal level of group participation. Additionally, designing activities that encourage more balanced interaction and collaboration on the content could be beneficial.

6. Conclusions

Following the implementation of the didactic sequence, the importance of considering the emotional dimension in motivating students and helping them connect with the content they engage with is highlighted. This approach allows for identifying strengths and areas for improvement. Integrating active methodologies into STEAM education within a controversial heritage context not only enhances meaningful learning but also stimulates epistemic and thematic emotions that foster curiosity, reflection, and critical thinking. For these experiences to have a positive impact, it is essential to provide students with autonomy and sufficient time for the development and application of technological activities. Additionally, promoting teamwork and ensuring that scientific content is not addressed in isolation, but rather connected to students’ emotions and experiences with their peers, could lead to a more engaging learning process.

The use of data collection sensors to analyze the physicochemical characteristics of the river primarily triggered epistemic emotions, such as curiosity and surprise, related to discovery and scientific exploration. These emotions encouraged interest in experimental learning and connection with real data, generating enthusiasm for scientific processes. However, negative emotions like frustration and anxiety also emerged, mainly due to technical difficulties and coordination issues in group work. This underscores the need for more structured technological activities, providing additional time and better instructional support to balance autonomy, guidance, and unfamiliar technological tools. Indeed, time constraints during the implementation of the sequence represented a limitation, reducing students’ opportunities to fully engage with and consolidate the technological components of the project. As noted by Stephan et al. (2019), a successful implementation of educational technologies requires not only technical fluency but also emotional support, particularly when students face novel or complex digital tasks.

On the other hand, the Río Tinto heritage stood out for its ability to elicit thematic emotions, such as admiration, enjoyment, and compassion. These emotions reflect how heritage can connect students with history, culture, and socio-environmental issues in their surroundings. Student comments on historical injustice and the river’s environmental impact suggest that this context fosters emotions linked to ethical reflection on the studied content. However, social emotions were notably scarce, indicating the need for improved and more collaborative heritage-related activities that encourage dialogue and student interaction.

Group work, whether in technological or heritage-related activities, yielded mixed results. While some students appreciated collaboration and learned from their peers, others experienced frustration due to tensions or a lack of group cohesion. This reinforces the importance of structuring collaborative work effectively, with clearly defined roles and objectives, to optimize the overall learning experience.

Compared to previous studies, such as those by Jiménez-Liso et al. (2021), Loderer et al. (2020), and Wang et al. (2024), the results suggest that active methodologies like inquiry and modeling, along with the use of technologies in the classroom, can generate significant epistemic emotions when students perceive a high level of control and value in their tasks. Wang et al. (2024) emphasize that combining inquiry-based learning with model-based reasoning in STEAM contexts fosters conceptual change and promotes positive emotional trajectories, such as curiosity, enjoyment, and pride. However, unlike these studies, the technology-related activities in this study showed a weaker connection to conceptual content, limiting the emergence of thematic emotions in some cases. This finding underscores the need to design activities that more effectively integrate practical skills while also eliciting emotions and motivations tied to conceptual understanding, maximizing both emotional and cognitive learning. Future research could further investigate gender-based differences in students’ emotional responses, particularly in relation to technological activities, collaborative work, or engagement with controversial heritage. Exploring this dimension would provide a deeper understanding of affective experiences in STEAM education and contribute to the design of more inclusive and equitable learning environments.

Author Contributions

Main conceptualization and original draft writing, A.C.C.-L.; methodological design, A.C.C.-L. with guidance from M.d.l.H.-P.; software and data curation, A.A.L.-M.; formal analysis and interpretation, A.C.C.-L.; supervision and critical review, M.d.l.H.-P. and A.A.L.-M.; project coordination, M.d.l.H.-P.; funding acquisition, M.d.l.H.-P. and A.A.L.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This article is part of the project “The socio-scientific controversy of the Río Tinto as a resource for identity development in students: Conserve or restore?”, approved in the 2022/2023 call for teaching innovation and educational research projects at the University of Huelva. It is also framed within the official inter-university PhD program in Teaching and Learning of Experimental Sciences, Social Sciences, Mathematics, and Physical and Sports Education. The research is linked to the R&D projects EPITEC2, “Controversial Heritage for Eco-Social Education” [(PID2020-116662GB-100)], funded by the MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033, and “Specialized Knowledge in Teacher Education for Mathematics, Experimental Sciences, and Social Sciences (MTSK-STSK-SCTSK)” [(ProyExcel_00297)], supported by the Regional Government of Andalusia. It is also connected to COIDESO (Research Center for Contemporary Thought and Innovation for Social Development) and the DESYM Research Group (Didactics of Experimental, Social and Mathematical Sciences).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to its observational nature, as it did not involve sensitive data, medical interventions, or risks to the participants.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to the teaching staff of the María Auxiliadora Charter School in Valverde del Camino, especially to Juanma Gemio for his unwavering support and dedication, as well as to all the coordinators involved in this project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Anwar, A., Rehman, I., Nasralla, M. M., Khattak, S. B. A., & Khilji, N. (2023). Emotions matter: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the detection and classification of students’ emotions in stem during online learning. Education Sciences, 13(9), 914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo-Mora, E., Sampedro-Martín, S., Martín-Cáceres, M. J., & Cuenca-López, J. M. (2022). Controversial heritage, ecosocial education and citizenship. connections for the development of heritage education in formal education. In D. Ortega-Sánchez (Ed.), Controversial issues and social problems for an integrated disciplinary teaching (pp. 35–52). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astleitner, H., & Leutner, D. (2014). Designing instructional technology from an emotional perspective. Journal of Research on Computing in Education, 32(4), 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badeo, J. M., & Duque, D. A. (2022). The effect of Socio-Scientific Issues (SSI) in teaching science: A meta-analysis study. Journal of Technology and Science Education, 12(2), 291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beniermann, A., Mecklenburg, L., & zu Belzen, A. U. (2021). Reasoning on controversial science issues in science education and science communication. Education Sciences, 11(9), 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campina-López, A. C., Arroyo-Mora, E., & Sampedro-Martín, S. (2025a). ¿Cómo ha sido el río Tinto y su entorno?: Patrimonios controversiales y pensamiento histórico en educación secundaria. In A. A. Lorca-Marín (Ed.), Huelva: Situaciones De Aprendizaje. Ediciones Octaedro. [Google Scholar]

- Campina-López, A. C., González Castanedo, Y., & Romero Fernández, R. (2025b). ¿Cómo es el río Tinto y su entorno?: Ecosistema y su geología en educación secundaria. In A. A. Lorca-Marín (Ed.), Huelva: Situaciones de aprendizaje. Ediciones Octaedro. [Google Scholar]

- Campina-López, A. C., Lorca-Marín, A. A., & de las Heras Pérez, M. (2025c). ¿Qué importancia tiene el río Tinto y su entorno?: Características fisicoquímicas y programación de sensores en Educación Secundaria. In A. A. Lorca-Marín (Ed.), Huelva: Situaciones de aprendizaje. Ediciones Octaedro. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, J. P., & Bellocchi, A. (2018). Emotions in learning science. Brill. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estepa, J., & Martín-Cáceres, M. J. (2018). Competencia en conciencia y expresiones culturales y educación histórica: Patrimonios en conflicto y pensamiento crítico. La educación histórica ante el reto de las competencias: Métodos, recursos y enfoques de enseñanza (pp. 75–86). ISBN 978-84-17219-85-7. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=6620208 (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Gao, L., Mun, K., & Kim, S. (2019). Using socioscientific issues to enhance students’ emotional competence. Research in Science Education, 51, 935–956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Madrona, P., Cejudo, J., Martínez-González, J. M., & López-Sánchez, G. F. (2019). Impact of the body mass index on affective development in physical education. Sustainability, 11(9), 2459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, T., & Hall, N. C. (2014). Academic boredom. In International handbook of emotions in education (pp. 311–330). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Hurtado, I., & Cuenca, J. M. (2022). Heritage education and special education: Working on emotions with differently abled people through heritage. Heritage & Society, 16, 22–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Villar, J., & Canessa Vicencio, F. (2019). Social emotions, heritage and recognition. The struggle of colina stonemasons in Santiago, Chile. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 25(12), 1263–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabau, L. J., & Ma, X. (2017). Science engagement and science achievement in the context of science instruction: A multilevel analysis of U.S. students and schools. International Journal of Science Education, 39(8), 1045–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenaway, K. H., Kalokerinos, E. K., & Williams, L. A. (2018). Context is Everything (in Emotion Research). Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 12(6), e12393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwet, K. L. (2021). Large-sample variance of fleiss generalized kappa. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 81(4), 781–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hargreaves, A. (1998). The emotions of teaching and educational change. In A. Hargreaves, A. Lieberman, M. Fullan, & D. Hopkins (Eds.), International handbook of educational change: Part one (pp. 558–575). Springer Netherlands. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huddleston, T., & Kerr, D. (2016). Vivir con la controversia: Cómo enseñar temas controvertidos mediante la Educación para la ciudadanía y los derechos humanos (EDC/HRE) Módulo de formación para el profesorado. GCED Clearinghouse. Available online: https://www.gcedclearinghouse.org/es/resources/vivir-con-la-controversia-c%C3%B3mo-ense%C3%B1ar-temas-controvertidos-mediante-la-educaci%C3%B3n-para-la?language=ar (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Jiménez-Liso, M. R., Bellocchi, A., Martinez-Chico, M., & Lopez-Gay, R. (2022). A model-based inquiry sequence as a heuristic to evaluate students’ emotional, behavioural, and cognitive engagement. Research in Science Education, 52(4), 1313–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Liso, M. R., Chico, M. M., & Lucio-Villegas, R. L.-G. (2023). Cómo enseñar a diseñar Secuencias de Actividades de Ciencias: Principios, elementos y herramientas de diseño. Revista Eureka sobre Enseñanza y Divulgación de las Ciencias, 20(3), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Liso, M. R., Delgado, L., Castillo-Hernández, F. J., & Baños, I. (2021). Contexto, indagación y modelización para movilizar explicaciones del alumnado de secundaria. Enseñanza de las Ciencias. Revista de Investigación y Experiencias Didácticas, 39(1), 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lajoie, S. P., Pekrun, R., Azevedo, R., & Leighton, J. P. (2020). Understanding and measuring emotions in technology-rich learning environments. Learning and Instruction, 70, 101272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtamo, S., Juuti, K., Inkinen, J., & Lavonen, J. (2018). Connection between academic emotions in situ and retention in the physics track: Applying experience sampling method. International Journal of STEM Education, 5(1), 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L., Gow, A. D. I., & Zhou, J. (2020). The role of positive emotions in education: A neuroscience perspective. Mind, Brain, and Education, 14(3), 220–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.-C., Lin, K. H.-C., & Li, C.-T. (2021). Employing STEAM 6E teaching methods to analyze the academic emotions of the digital video practice course. In Y.-M. Huang, C.-F. Lai, & T. Rocha (Eds.), Innovative technologies and learning (pp. 584–592). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, D., & Kearney, M.-L. (2019). The role of emotions in higher education teaching and learning processes. Studies in Higher Education, 44(10), 1707–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loderer, K., Pekrun, R., & Lester, J. C. (2020). Beyond cold technology: A systematic review and meta-analysis on emotions in technology-based learning environments. Learning and Instruction, 70, 101162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupión-Cobos, T., & García-Ruiz, C. (2024). Indagación científica escolar y educación STEAM: Formación del profesorado y enseñanza para la transferencia a las aulas (Vol. 81). ISBN/EAN: 9788412872392. Especialistas en educación. Graó. Available online: https://www.grao.com/libros/indagacion-cientifica-escolar-y-educacion-steam-78773 (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Martínez-Borreguero, G., Mateos-Nuñez, M., & Naranjo-Correa, F. L. (2019, July 1–3). Analysis of the emotions of secondary school students in stem areas [Edulearn 19 Proceedings]. 11th International Conference on Education and New Learning Technologies (pp. 724–733), Palma de Mallorca, Spain. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellado, V., Borrachero, A. B., Brígido, M., Melo, L. V., Dávila, M. A., & Cañada, F. (2014). Las emociones en la enseñanza de las ciencias. Enseñanza de las Ciencias. Revista de Investigación y Experiencias Didácticas, 32(3), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, L. L., Rite, M. T., & Soto, N. A. R. (2023). Patrimonio y emociones en el alumnado de ESO: Análisis de una experiencia en el museo. REIDICS. Revista de Investigación en Didáctica de las Ciencias Sociales, 12, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, J. N., & Hackett, E. J. (2012). Hot spots and hot moments in scientific collaborations and social movements. American Sociological Review, 77(1), 21–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R. (2000). 7—A social-cognitive, control-value theory of achievement emotions. In J. Heckhausen (Ed.), Advances in psychology (Vol. 131, pp. 143–163). North-Holland. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R. (2006). The control-value theory of achievement emotions: Assumptions, corollaries, and implications for educational research and practice. Educational Psychology Review, 18(4), 315–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., Titz, W., & Perry, R. P. (2002). Academic emotions in students’ self-regulated learning and achievement: A program of qualitative and quantitative research. Educational Psychologist, 37(2), 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R., & Linnenbrink-Garcia, L. (2012). Academic emotions and student engagement. In S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 259–282). Springer US. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R., & Linnenbrink-Garcia, L. (Eds.). (2014). International handbook of emotions in education. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R., & Perry, R. P. (2014). Control-value theory of achievement emotions. In International handbook of emotions in education (pp. 120–141). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Perignat, E., & Katz-Buonincontro, J. (2019). STEAM in practice and research: An integrative literature review. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 31, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Bueno, B., Pérez, M. Á. d. l. H., & Jiménez-Pérez, R. (2024). Enfoques académicos de las emociones hacia la Física en maestros en formación inicial. Enseñanza de las Ciencias. Revista de Investigación y Experiencias Didácticas, 42(2), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postareff, L., Mattsson, M., Lindblom-Ylänne, S., & Hailikari, T. (2017). The complex relationship between emotions, approaches to learning, study success and study progress during the transition to university. Higher Education, 73(3), 441–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Real Decreto 217/2022. (2022). De 29 de marzo, por el que se establece la ordenación y las enseñanzas mínimas de la Educación Secundaria Obligatoria. (s. f.). Ministerio de Educación y Formación Profesional. Available online: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2022-4975 (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- Retana-Alvarado, D., Pérez, M., Vázquez-Bernal, B., & Perez, R. (2023). El cambio en las emociones de futuros maestros en la interacción con una enseñanza de las ciencias basada en indagación. Tecné Episteme y Didaxis TED, 53, 137–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadler, T. D., Barab, S. A., & Scott, B. (2007). What do students gain by engaging in socioscientific inquiry? Research in Science Education, 37(4), 371–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampedro-Martín, S., Mora, E., Cuenca-Lopez, J., & Cáceres, M. J. (2022). Controversial heritage for eco-citizenship education in Social Science didactics. In Re-imagining the teaching of european history (pp. 68–79). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santacana, J., & Martínez, T. (2018). El patrimonio cultural y el sistema emocional: Un estado de la cuestión desde la didáctica. Arbor, 194(788), 788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sáenz-López Buñuel, P. (2020). Educar emocionando. Universidad de Huelva. [Google Scholar]

- Schutz, P. A., & Lanehart, S. L. (2002). Introduction: Emotions in education. Educational Psychologist, 37(2), 67–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, A., & Ashworth, E. L. (2018). Emotionality and STEAM integrations in teacher education. Journal of Teaching and Learning, 11(2), 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, M., Markus, S., & Gläser-Zikuda, M. (2019). Students’ achievement emotions and online learning in teacher education. Frontiers in Education, 4, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.-L., Samsudin, M. A., Ismail, M. E., Ahmad, N. J., & Abdul Talib, C. (2021). Exploring the effectiveness of STEAM integrated approach via scratch on computational thinking. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 17(12), em2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toma, R. B., & García-Carmona, A. (2021). «De STEM nos gusta todo menos STEM». Análisis crítico de una tendencia educativa de moda. Enseñanza de las Ciencias. Revista de Investigación y Experiencias Didácticas, 39(1), 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trabajo, M., & Cuenca, J. (2022). Educación patrimonial y sostenibilidad: Un estudio de caso en enseñanza secundaria obligatoria. Educação & Sociedade, 43, e255220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyng, C. M., Amin, H., Saad, M., & Malik, A. (2017). The influences of emotion on learning and memory. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., & Hsu, K.-C. (2023). How teaching quality and students’ academic emotions influence university students’ learning effecitiveness. In Communications in computer and information science (Vol. 1830, pp. 328–341). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Wang, Y., Pan, Z., & Ortega-Martín, J. L. (2024). The predicting role of efl students’ achievement emotions and technological self-efficacy in their technology acceptance. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 33(4), 771–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).