Empowering Pre-Service Teachers as Enthusiastic and Knowledgeable Reading Role Models Through Engagement in Children’s Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Pre-survey: The initial planning phase involved a pre-survey assessing PSTs’ attitudes and behaviours towards reading. The results highlighted areas for development and informed the design of targeted pedagogical responses;

- Pedagogical intervention: Informed by the pre-survey data, the second phase implemented a pedagogical intervention in which children’s literature was intentionally integrated into Bachelor of Education (BEd) coursework. This integration aimed to model how literary texts can be used to engage primary students in English curriculum learning while also building PSTs’ confidence and capability in using such texts in their future classrooms. A range of RfE practices supported this approach.

2. The Current Context of Reading Instruction

3. The Need for Enthusiastic, Knowledgeable Reading Teachers

4. Initial Teacher Education Preparation

5. The Theoretical Framework

6. The Research Aims

7. Research Design

- Planning: Identifying the problem through a pre-survey of PSTs’ reading attitudes and behaviours;

- Acting: Designing and implementing a pedagogical intervention that integrates children’s literature and RfE practices into BEd coursework;

- Observing: Gathering post-intervention data through a follow-up survey and semi-structured interviews;

- Reflecting: Analysing the impact of the intervention to inform future practice, challenge assumptions, and contribute to the transformation of educational practices.

7.1. The Planning Phase

7.2. The Acting Phase

8. Preliminary Insights and Discussion

8.1. Active Engagement with Texts

8.2. Widening Reading Repertoires

9. Summary

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- AlShamsi, A. S., AlShamsi, A. K., & AlKetbi, A. N. (2022). Training teachers using action research for innovation in early childhood education literacy. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 21(11), 54–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Applegate, A., & Applegate, M. (2004). The Peter effect: Reading habits and attitudes of preservice teachers. The Reading Teacher, 57(6), 554–563. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Curriculum and Reporting Authority [ACARA]. (2022a). Australian curriculum: English. Available online: https://v9.australiancurriculum.edu.au/f-10-curriculum/learning-areas/english/foundation-year_year-1_year-2_year-3_year-4_year-5_year-6?view=quick&detailed-content-descriptions=0&hide-ccp=0&hide-gc=0&side-by-side=1&strands-start-index=0&subjects-start-index=0 (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Australian Curriculum and Reporting Authority [ACARA]. (2022b). Australian curriculum English: Understanding this learning area. Available online: https://v9.australiancurriculum.edu.au/teacher-resources/understand-this-learning-area/english (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority [ACARA]. (2023). National report on schooling in Australia 2023. Available online: https://dataandreporting.blob.core.windows.net/anrdataportal/ANR-Documents/nationalreportonschoolinginaustralia_2023.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Australian Government Department of Education. (2023). Strong beginnings: Report of the teacher education expert panel 2023. Available online: https://www.education.gov.au/download/16510/strong-beginnings-report-teacher-education-expert-panel/33698/document/pdf (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Bland, J. (2019). Teaching English to young learners: More teacher education and more children’s literature. CLELE Journal, 7(2), 79–103. [Google Scholar]

- Bottoms, S. I., Pegg, J., Adams, A., Risser, H. S., & Wu, K. (2020). Mentoring within communities of practice. In B. J. Irby, J. N. Boswell, L. J. Searby, F. Kochan, R. Garza, & N. Abdelrahman (Eds.), The Wiley international handbook of mentoring (pp. 141–166). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowers, J. S. (2020). Reconsidering the evidence that systematic phonics is more effective than alternative methods of reading instruction. Educational Psychology Review, 32(3), 681–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breeze, T., O’Dubhchair, E., & Dafydd, S. (2025). Holistic, aspirational professional standards as a boundary object between communities of practice for pre-service teachers. Oxford Review of Education, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bright, R. (2017). The lion inside (J. Field, Illus.). Orchard Books. [Google Scholar]

- Brodie, W. (2023). Review of university teaching courses: IEUA submission. Independent Education, 53(2), 16–17. [Google Scholar]

- Brosseuk, D. (2020). Children’s literature as the heart of literacy teaching. In R. Ewing, S. O’Brien, K. Rushton, L. Stewart, R. Burke, & D. Brosseuk (Eds.), English and literacies (pp. 154–178). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bulut, B., & Ertem, İ. S. (2018). A think-aloud study: Listening comprehension strategies used by primary school students. Journal of Education and Training Studies, 6(5), 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervetti, G. N., Pearson, P. D., Palincsar, A. S., Afflerbach, P., Kendeou, P., Biancarosa, G., Higgs, J., Fitzgerald, M. S., & Berman, A. I. (2020). How the reading for understanding initiative’s research complicates the simple view of reading invoked in the science of reading. Reading Research Quarterly, 55(S1), S161–S172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, A. S. W., & Ghani, K. A. (2021). The use of think-aloud in assisting reading comprehension among primary school students. Journal of Cognitive Sciences and Human Development, 7(1), 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cissi, E., Kruep, R. S., & Goldsmith, C. (2024). Beyond book clubs: Establishing a network of teacher-readers through community, purpose, and joy. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 68(3), 254–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, C., & Rumbold, K. (2006). Reading for pleasure: A research overview. National Literacy Trust. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED496343 (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Cremin, T. (2019). Reading communities: Why, what and how? NATE Primary Matters. Available online: https://oro.open.ac.uk/60382/1/P4-8_Reading%20Communities%20Teresa%20Cremin_Final.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Cremin, T., Bearne, E., Mottram, M., & Goodwin, P. (2007). Teachers as readers phase 1 (2006–7) research report. Available online: https://ourfp.org/wp-content/uploads/Teachers_as_Readers_Phase_1_Research_Report-1.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Cremin, T., Bearne, E., Mottram, M., & Goodwin, P. (2008). Primary teachers as readers. English in Education, 42(1), 8–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremin, T., Hendry, H., Rodriguez Leon, L., & Kucirkova, N. (Eds.). (2022). Reading teachers: Nurturing reading for pleasure. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cremin, T., Mottram, M., Collins, F., Powell, S., & Safford, K. (2009). Teachers as readers: Building communities of readers. Literacy, 43(1), 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremin, T., Mottram, M., Collins, F., Powell, S., & Safford, K. (2014). Building communities of engaged readers: Reading for pleasure. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cremin, T., Mukherjee, S. J., Aerila, J., Kauppinen, M., Siipola, M., & Lähteelä, J. (2024). Widening teachers’ reading repertoires: Moving beyond a popular childhood canon. The Reading Teacher, 77(6), 833–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremin, T., & Scholes, L. (2024). Reading for pleasure: Scrutinising the evidence base–benefits, tensions and recommendations. Language and Education, 28(4), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawes, E. T., Cunningham, K. E., Enriquez, G., & Cappiello, M. A. (2023). Reading with purpose: Selecting and using children’s literature for inquiry and engagement. Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dengler, K. (2018). Aliterate pre-service teachers’ reading histories: An exploratory multiple case study [Doctoral dissertation, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing]. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. (1934). Art as experience. Minton, Balch and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Dorfman, L. R., & Cappelli, R. (2023). Mentor texts: Teaching writing through children’s literature, K–6 (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- English, R. (2021). Teaching and learning through children’s literature: Teaching through mentor texts. Practical Literacy, 26(1), 37–39. [Google Scholar]

- Flores, T. T., Vlach, S. K., & Lammert, C. (2019). The role of children’s literature in cultivating preservice teachers as transformative intellectuals: A literature review. Journal of Literacy Research, 51(2), 214–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, M. (2017). I’m Australian too (R. Ghosh, Illus.). Omnibus Books. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, K. (2023). Write like this: Teaching real-world writing through modeling and mentor texts. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godwin, J. (2023). Can you teach a fish to climb a tree? (T. Denton, Illus.). Hardie Grant Children’s Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin, A. P., & Jiménez, R. T. (2021). The science of reading: Supports, critiques, and questions. Reading Research Quarterly, 56(S1), S7–S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M. (2025a). What do you do with a problem? A radical autoethnographic response to the TEEP report. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 53(1), 50–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, M. (2025b, February 3). Reading: How to prioritise reading for enjoyment in classrooms. AARE EduResearch Matters. Available online: https://blog.aare.edu.au/reading-how-to-prioritise-reading-for-enjoyment-in-classrooms/ (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Green, M., Gaunt, L., & Barton, G. (2025). Using children’s picture books to teach mathematical and/or numeracy concepts: An exploration of the aesthetic value of mathematics for preservice teachers’ dispositions [Unpublished manuscript]. Faculty of Education, Southern Cross University. [Google Scholar]

- Guthrie, J. T., & Wigfield, A. (2000). Engagement and motivation in reading. In M. L. Kamil, P. B. Mosenthal, P. D. Pearson, & R. Barr (Eds.), Handbook of reading research (Vol. 3, pp. 3403–3422). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, M. A. K. (1985). An introduction to functional grammar. Edward Arnold. [Google Scholar]

- Halliday, M. A. K. (2009). The essential Halliday. Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Hanford, E. (2018, September 10). Hard words: Why aren’t kids being taught to read? APM Reports. Available online: https://www.apmreports.org/episode/2018/09/10/hard-words-why-american-kids-arent-being-taught-to-read (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Hikida, M., Chamberlain, K., Tily, S., Daly-Lesch, A., Warner, J. R., & Schallert, D. L. (2019). Reviewing how preservice teachers are prepared to teach reading processes: What the literature suggests and overlooks. Journal of Literacy Research, 51(2), 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hindman, A. H., Morrison, F. J., Connor, C. M., & Connor, J. A. (2020). Bringing the science of reading to preservice elementary teachers: Tools that bridge research and practice. Reading Research Quarterly, 55, S197–S206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, K. S., & Roop, T. D. (2021). Missing pieces and voices: Steps for teachers to engage in science of reading policy and practice. Michigan Reading Journal, 54(1), 9. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, J., Stobart, A., & Haywood, A. (2024). The reading guarantee: How to give every child the best chance of success. Available online: https://grattan.edu.au/report/reading-guarantee/ (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Jackson, D., Johnson, W. F., Frankel, K. K., & Houston-King, A. (2025). Preserving integrative and humanizing literacies: A commentary on the current literacy debates and the narrowing of literacy instruction. Reading Research Quarterly, 60(1), e594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez-Silva, M., & Olson, K. (2012). A community of practice in teacher education: Insights and perceptions. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 24(3), 335–348. [Google Scholar]

- Kemmis, S., & McTaggart, R. (1988). The action research planner. Deakin University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kemmis, S., McTaggart, R., & Nixon, R. (2014). The action research planner: Doing critical participatory action research. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- King, C. U., Boyd, M. P., & Reid, S. D. (2024). Creating dialogic space around purposeful selection for reading and teaching diverse children’s literature. Theory into Practice, 63(2), 170–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konza, D. (2014). Teaching reading: Why the “fab five” should be the “big six”. The Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 39(12), 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laminack, L. (2017). Mentors and mentor texts: What, why, and how? The Reading Teacher, 70(6), 753–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- la Velle, L. (2020). Professional knowledge communities of practice: Building teacher self-efficacy. Journal of Education for Teaching, 46(5), 613–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leahy, M. A., & Foley, B. C. (2018). Diversity in children’s literature. World Journal of Educational Research, 5(2), 172–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledger, S., & Merga, M. (2018). Reading aloud: Children’s attitudes toward being read to at home and at school. The Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 43(3), 124–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leland, C. H., Lewison, M., & Harste, J. C. (2022). Teaching children’s literature: It’s critical! Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Likert, R. (1932). A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Archives of Psychology, 140, 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- MacPhee, D., & Sanden, S. (2016). Motivated to engage: Learning from the literacy stories of preservice teachers. Reading Horizons, 55(1), 16. Available online: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3179&context=reading_horizons (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Martin, A. D., & Spencer, T. (2020). Children’s literature, culturally responsive teaching, and teacher identity: An action research inquiry in teacher education. Action in Teacher Education, 42(4), 387–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrane, J., Stiff, J., Baird, J.-A., Lenkeit, J., & Hopfenbeck, T. (2017). Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS): National report for England. UK Department for Education. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/pirls-2016-reading-literacy-performance-in-england (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Meeks, L., & Stephenson, J. (2020). Australian preservice teachers and early reading instruction. Australian Journal of Learning Difficulties, 25(1), 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milne, J. (2024). Developing volitional readers requires breadth and balance: Skills alone won’t do it. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 59(1), 289–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moody, S., Hu, X., Kuo, L.-J., Jouhar, M., Xu, Z., & Lee, S. (2018). Vocabulary instruction: A critical analysis of theories, research, and practice. Education Sciences, 8(4), 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muela, D., Tabernero, R., & Hernández, L. (2024). Investigating primary pre-service teachers’ perceptions of nonfiction picturebooks. The Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 47(2), 281–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz, C., Arriaza, V., Acuña Luongo, N., & Valenzuela, J. (2022). Chilean preservice teachers and reading: A first look of a complex relationship. The Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 45(2), 265–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathanson, S., Pruslow, J., & Levitt, R. (2008). The reading habits and literacy attitudes of inservice and prospective teachers: Results of a questionnaire survey. Journal of Teacher Education, 59(4), 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nel, C., Dieker, L., & Marais, E. (2024). The integration of mixed reality simulation into reading literacy modules. Education Sciences, 14(10), 1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, M. (2023). Teachers’ scaffolding roles during picturebook read-alouds in the primary English language classroom. Children’s Literature in English Language Education, 11(1), 43–67. [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development [OECD]. (2023). PISA 2022 results (Volume I): The state of learning and equity in education. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/pisa-2022-results-volume-i_53f23881-en/full-report.html (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- O’Sullivan, O., & McGonigle, S. (2010). Transforming readers: Teachers and children in the centre for literacy in primary education power of reading project. Literacy, 44(2), 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxley, E., & McGeown, S. (2023). Reading for pleasure practices in school: Children’s perspectives and experiences. Educational Research, 65(3), 375–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parliament of Victoria. (2024). The state education system in Victoria. Available online: https://www.parliament.vic.gov.au/4ae944/contentassets/93438d4b371d406bb3935e4c226317a5/lclsic-60-03-inquiry-into-the-state-education-system-in-victoria.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Powell, S. (2014). Influencing children’s attitudes, motivation and achievements. In T. Cremin, M. Mottram, F. M. Collins, S. Powell, & K. Safford (Eds.), Building communities of engaged readers: Reading for pleasure (pp. 128–146). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Price-Mohr, R., & Price, C. (2020). A comparison of children aged 4–5 years learning to read through instructional texts containing either a high or a low proportion of phonically-decodable words. Early Childhood Education Journal, 48(1), 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Queensland Government Department of Education. (2023a). Effective teaching of reading: Overview of the literature. Department of Education, Queensland Government. Available online: https://education.qld.gov.au/curriculums/Documents/literature-review.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Queensland Government Department of Education. (2023b). Reading position statement. Available online: https://education.qld.gov.au/curriculums/Documents/reading-position-statement.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Rand, P., & Snyder, C. (2021). Bridge over troubled water: A teacher education program’s emergent methods for constructing an online community of practice during a global pandemic. Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice, 21(11), 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinking, D., Hruby, G. G., & Risko, V. J. (2023). Legislating phonics: Settled science or political polemics? Teachers College Record, 125(1), 104–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, P. H. (2018). The word collector (P. H. Reynolds, Illus.). Scholastic. [Google Scholar]

- Rudge, L. (2016). Gary. Walker Books Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Sagor, R. D., & Williams, C. (2016). The action research guidebook: A process for pursuing equity and excellence in education (3rd ed.). Corwin. [Google Scholar]

- Scheffel, T.-L., Cameron, C., Dolmage, L., Johnston, M., Lapensee, J., Solymar, K., Speedie, E., & Wills, M. (2018). A collaborative children’s literature book club for teacher candidates. Reading Horizons, 57(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, A. (2016). The use of children’s literature in teaching: A study of politics and professionalism within teacher education. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Sönmez, Y., & Süleyman, E. S. (2018). The effect of the thinking-aloud strategy on the reading comprehension skills of 4th grade primary school students. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 6(1), 168–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.-J., Sahakian, B. J., Langley, C., Yang, A., Jiang, Y., Kang, J., Zhao, X., Li, C., Cheng, W., & Feng, J. (2023). Early-initiated childhood reading for pleasure: Associations with better cognitive performance, mental well-being and brain structure in young adolescence. Psychological Medicine, 54(2), 359–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavsancıl, E., Yıldırım, O., & Demır, S. B. (2019). Direct and indirect effects of learning strategies and reading enjoyment on PISA 2009 reading performance. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research, 19(82), 169–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temple, K., & Temple, J. (2019). Room on our rock (T. R. Baynton, Illus.). Scholastic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, M., Yao, Y., Wright, K. L., & Kreiner, D. (2023). Teachers as readers: Baseline profile types with regard to skills, habits, and dispositions. Reading Psychology, 44(8), 1005–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, I. (2025). Tackling social disadvantage through teacher education. Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Tompkins, G., Smith, C., Campbell, R., & Green, D. (2019). Literacy for the 21st Century: A balanced approach (3rd ed.). Pearson Education Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Tovey, S. (2022). Engaging the reluctant preservice teacher reader: Exploring possible selves with literature featuring teachers. Action in Teacher Education, 44(4), 271–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truscott, D., & Barker, K. S. (2020). Developing teacher identities as in situ teacher educators through communities of practice. The New Educator, 16(4), 333–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization [UNESCO]. (2021). Futures of education: Reimagining how knowledge and learning can shape the future of humanity and the planet. UNESCO. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000379707 (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Van Bergen, P., Ryan, M., Cliff, K., Ledger, S., Simons, M., Zundans-Fraser, L., Gregory, S., Adlington, R., Youdell, D., Andrews, R., Monteleone, C., & Little, C. (2024). Preliminary report: Who says what about initial teacher education and whose perspectives are heard? NSW Council of Deans of Education. Available online: http://nswcde.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/nswcde-strategic-teep-mapping-project_preliminary-report.pdf (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Walsh, K., & Bracken, M. (2023). The reading aloud resource book: A practical guide for developing language using picture books. Taylor and Francis. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanamaker, K., & Bestwick, A. (2022). Using book tasting in the academic library: A tale of children’s literature, collaboration, and an increased appetite for books. Collection Management, 47(2–3), 179–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waugh, R., & Waugh, D. (2022). Integrating children’s literature in the classroom: Insights for the primary and early years educator. McGraw-Hill Education. [Google Scholar]

- Webber, C., Wilkinson, K., Duncan, L., & McGeown, S. (2023). Approaches for supporting adolescents’ reading motivation: Existing research and future priorities. In Frontiers in education (Vol. 8, p. 1254048). Frontiers Media SA. [Google Scholar]

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, A. (2015). Exploring the perceptions and motivations of pre-service elementary teachers towards aesthetic reading in an undergraduate course in literature for children. Available online: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/honorstheses1990-2015/606/ (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Wyse, D., & Hacking, C. (2024). The balancing act: An evidence-based approach to teaching phonics, reading and writing. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

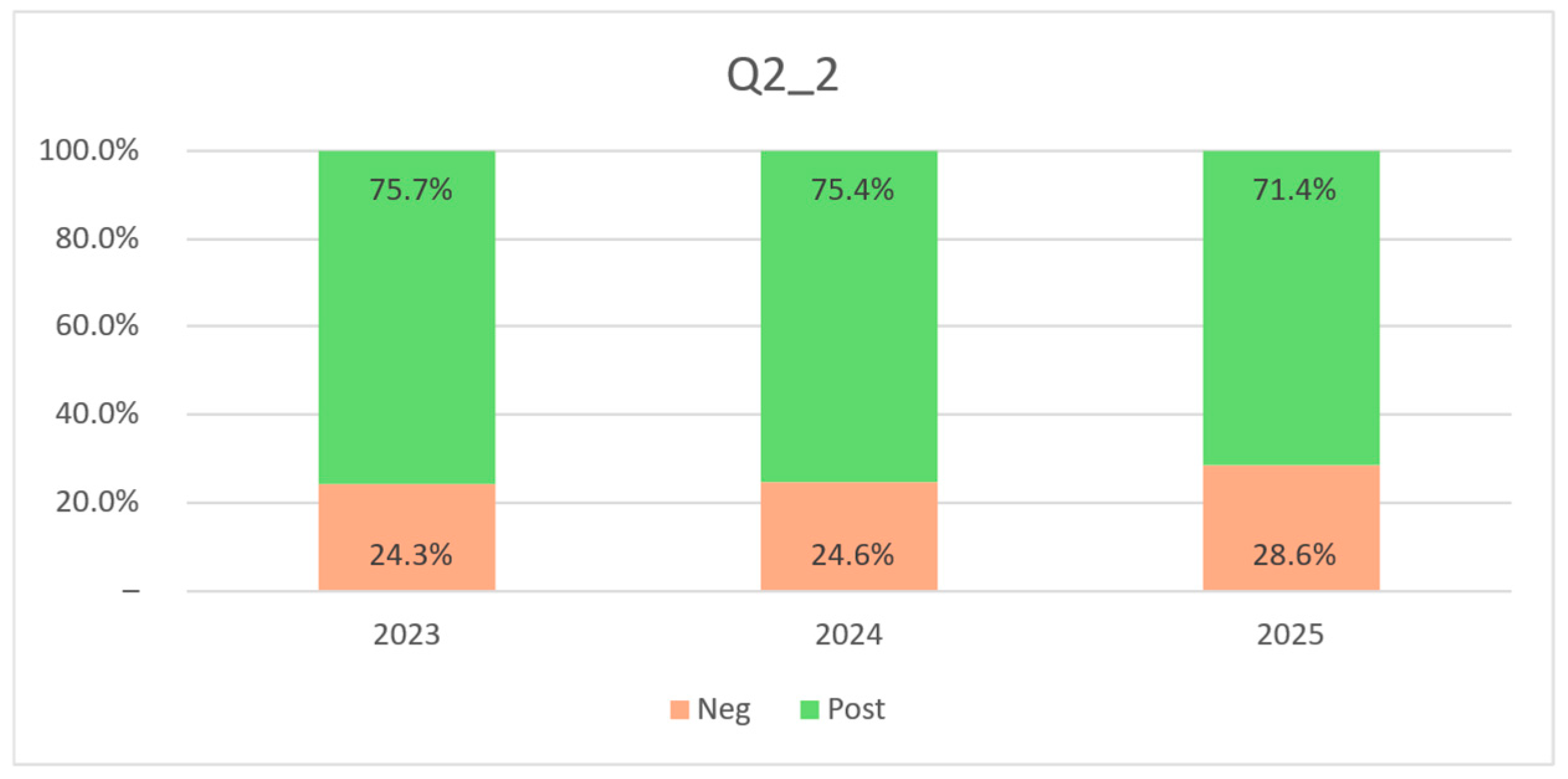

| Q2.2 | Year | Strongly Disagree | Somewhat Disagree | Not Applicable to My Life | Somewhat Agree | Strongly Agree | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I pay close attention to and actively engage in books I personally choose. | 2023 | 2 (5.4%) | 4 (10.8%) | 3 (8.1%) | 14 (37.8%) | 14 (37.8%) | 37 |

| 2024 | 1 (1.6%) | 7 (11.5%) | 7 (11.5%) | 23 (37.7%) | 23 (37.7%) | 61 | |

| 2025 | 2 (3.6%) | 6 (10.7%) | 8 (14.3%) | 19 (33.9%) | 21 (37.5%) | 56 |

| Children’s Book: Reynolds, P. H. (2018). The Word Collector (P. H. Reynolds, Illus.). Scholastic. | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Australian Curriculum: English content | Children’s Book Features | ITE University Coursework Topics/Concepts/Content for Discussion | |

| Understand how to apply knowledge of phoneme–grapheme (sound–letter) relationships, syllables, and blending and segmenting to fluently read and write multisyllabic words with more complex letter patterns AC9E3LY09 | Bohemian Brilliance Effervescent Geometry Guacamole Kaleidoscope Onomatopoeia Symphony Torrential Vociferous | Metalinguistic awareness: Subject-specific terminology E.g., define phonemes and graphemes of English and process of decoding: Grapheme Phonemes Blending Segmenting Complex letter patterns | |

| Understand how to apply knowledge of common base words, prefixes, suffixes, and generalisations for adding a suffix to a base word to read and comprehend new multimorphemic words AC9E3LY10 | Wonderful Powerful Attention Collection Infinite Favourite | Collect Collected Collecting Collection Aromatic Poetic Electric | Key definitions of literacy according to: UNESCO ILA ALEA ACARA NSW Department of Education QLD Department of Education |

| Understand that verbs are anchored in time through tense AC9E3LA08 | Collect Did collect Collected Saw Caught Began organising Began stringing Had not imagined Was thinking | Study strategies: Reading comprehension Academic reading Professional reading Using English curriculum/syllabus glossaries | |

| Understand how verbs represent different processes for doing, feeling, thinking, saying, and relating AC9E3LA07 | Caught Jumped Popped Moved Knew Imagined Understand Noticed | Were Become Being Describe | Preparing for assessments: Academic writing competencies Professional writing competencies Spelling Punctuation Grammar Cohesion |

| Understand that a clause is a unit of grammar usually containing a subject and a verb that need to agree AC9E3LA06 |

| Grammatical competence: Phrase structure. Simple sentence structure. Compound sentence structure. Complex sentence structure. | |

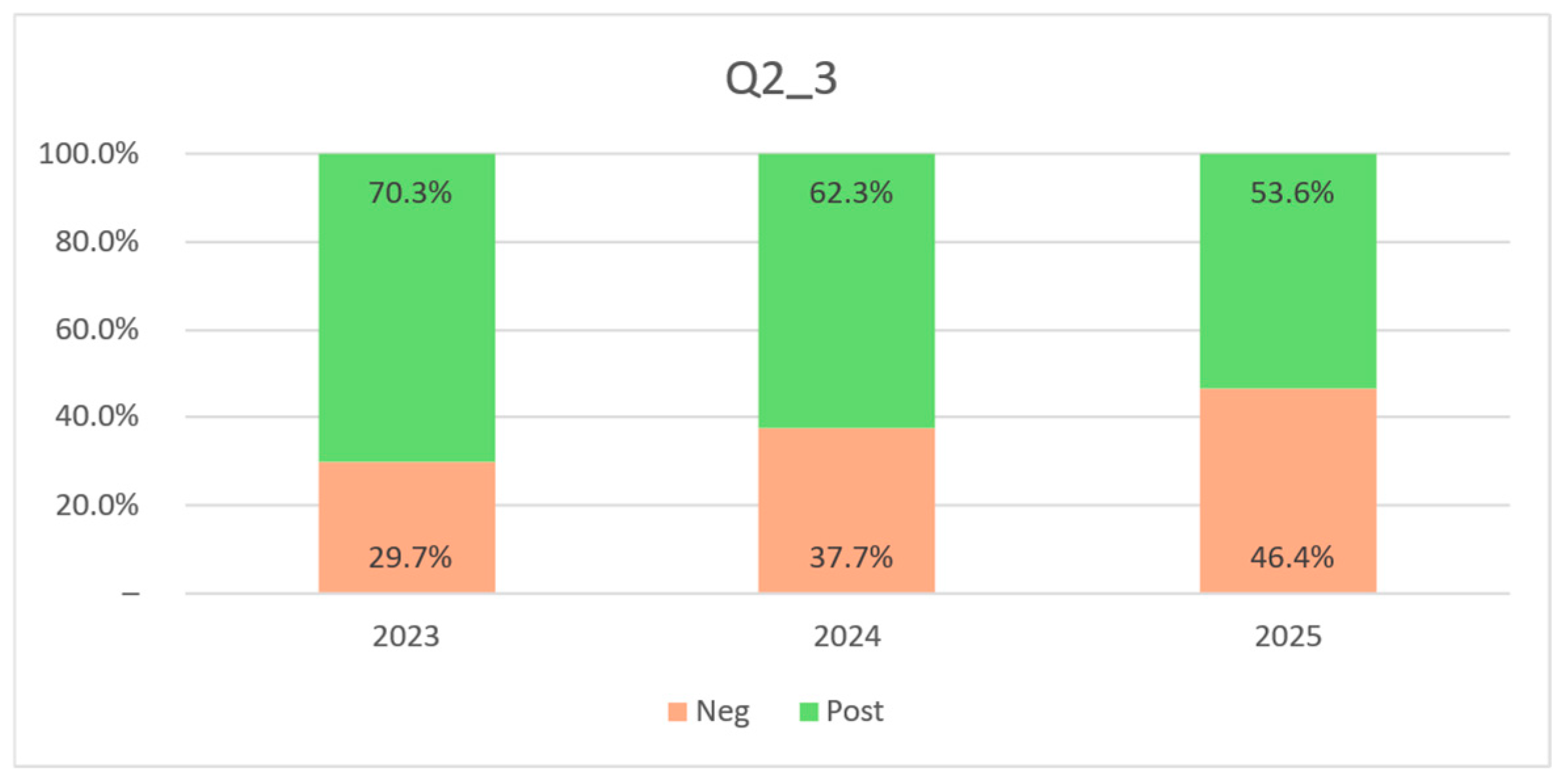

| Q2.3 | Year | Strongly Disagree | Somewhat Disagree | Not Applicable to My Life | Somewhat Agree | Strongly Agree | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I read regularly and widely to expand my knowledge and understanding. | 2023 | 1 (2.7%) | 6 (16.2%) | 4 (10.8%) | 22 (59.5%) | 4 (10.8%) | 37 |

| 2024 | 1 (1.6%) | 16 (26.2%) | 6 (9.8%) | 35 (57.4%) | 3 (4.9%) | 61 | |

| 2025 | 4 (7.1%) | 20 (35.7%) | 2 (3.6%) | 25 (44.6%) | 5 (8.9%) | 56 |

| Foundation | Year 1 | Year 2 | Year 3 | Year 4 | Year 5 | Year 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year level descriptions: Each year level has a description with an overview of the learning students should experience. This row displays excerpts from the Australian Curriculum: English v9.0 that pertain to the wide range of literary texts, structures, and features that students are entitled to learn about and from across the primary years. | Across all years: Students engage with a variety of texts for enjoyment. | ||||||

| The range of literary texts for Foundation to Year 10 comprises the oral narrative traditions and literature of First Nations Australians and classic and contemporary literature from wide-ranging Australian and world authors, including texts from and about Asia | |||||||

| Texts may include traditional oral texts, picture books, various types of stories, rhyming verse, poetry, non-fiction, film, multimodal texts, and dramatic performances. Foundation students develop their reading in a text-rich environment through engagement with a range of texts. This range includes literature that expands and reflects their world and texts that support learning in English and across the curriculum… Developing readers engage with some authentic texts that involve straightforward sequences of events and everyday happenings, some less familiar content, and a small range of language features, including simple and compound sentences, high-frequency words, and other words that can be decoded using developing phonic knowledge. | Texts may include picture books, various types of stories, rhyming verse, poetry, non-fiction, various types of information texts, short films and animations, dramatic performances, and texts used by students as models for constructing their own texts. Year 1 students develop their reading in a text-rich environment through engagement with a range of texts. This range includes literature that expands and reflects their world and texts that support learning in English and across the curriculum… Developing readers engage with authentic texts that support and extend them as independent readers. These texts include straightforward sequences of events and everyday happenings with recognisably realistic or imaginary characters… These texts use a small range of language features, including simple and compound sentences, some unfamiliar vocabulary, high-frequency words, and other words that need to be decoded using developing phonic knowledge. | Texts may include oral texts, picture books, various types of print and digital stories, simple chapter books, rhyming verse, poetry, non-fiction, various types of information texts, short films and animations, multimodal texts, dramatic performances, and texts used by students as models for constructing their own work. As Year 2 students transition to become independent readers, they continue to develop their decoding and comprehension skills using a range of texts. Literary texts may include sequences of events that span several pages, unusual happenings within a framework of familiar experiences and may include images that extend meaning. These texts include language features such as varied sentence structures, some unfamiliar vocabulary, a significant number of high-frequency words, more complex words that need to be decoded using phonic and morphemic knowledge, and a range of punctuation conventions. | Texts may include oral texts, picture books, various types of print and digital texts, chapter books, rhyming verse, poetry, non-fiction, film, multimodal texts, dramatic performances, and texts used by students as models for constructing their own work. Literary texts may describe events that extend over several pages, unusual happenings within a framework of familiar experiences and may include images that extend meaning. These texts use language features including varied sentence structures, some unfamiliar vocabulary, a significant number of high-frequency words that can be decoded using phonic and morphemic knowledge, a variety of punctuation conventions, and illustrations and diagrams that support and extend the printed text. | Texts may include oral texts, picture books, various types of print and digital texts, short novels of different genres, rhyming verse, poetry, non-fiction, film, multimodal texts, dramatic performances, and texts used by students as models for creating their own work. Literary texts that support and extend students in Year 4 as independent readers may describe sequences of events that develop over chapters and unusual happenings within a framework of familiar experiences… These texts use language features including varied sentence structures, some unfamiliar vocabulary that may include English words derived from other languages, a significant number of high-frequency words, words that need to be decoded using phonic and morphemic knowledge, a variety of punctuation conventions, and illustrations and diagrams that support and extend the printed text. | Texts may include film and digital texts, novels, poetry, non-fiction, and dramatic performances. The features of these texts may be used by students as models for creating their own work. Literary texts that support and extend students in Year 5 as independent readers may include complex sequences of events, elaborated events including flashbacks and shifts in time, and a range of characters. These texts may explore themes of interpersonal relationships and ethical dilemmas in real-world and imagined settings. Language features may include complex sentences, unfamiliar technical vocabulary, figurative language, and information presented in various types of images and graphics. Texts may reveal that the English language is dynamic and changes over time. | Texts may include film and digital texts, novels, poetry, non-fiction, and dramatic performances. The features of these texts may be used by students as models for creating their own work. Literary texts that support and extend students in Year 6 as independent readers may include elaborated events, including flashbacks and shifts in time, and a range of less predictable characters. These texts may support students’ understanding of authors’ styles. They may explore themes of interpersonal relationships and ethical dilemmas in real-world and imagined settings... Text structures may include chapters, headings and subheadings, tables of contents, indexes, and glossaries. Language features include complex sentences, unfamiliar technical vocabulary, figurative and idiomatic language, and information presented in various types of images and graphics. | |

| Achievement Standards: The achievement standard describes the expected quality of learning students should typically demonstrate. This row displays two/three Achievement Standards from the Australian Curriculum: English (2022a) that pertain to reading development across the primary years from F-6 | Read, view, and comprehend texts, making connections between characters, settings, and events and to personal experiences | Read, view, and comprehend texts, monitoring meaning and making connections between the depiction of characters, settings, and events and personal experiences | Read, view, and comprehend texts, identifying literal and inferred meaning and how ideas are presented through characters and events | Read, view, and comprehend texts, recognising their purpose and audience | Read, view, and comprehend texts created to inform, influence, and/or engage audiences | Read, view, and comprehend texts created to inform, influence, and/or engage audiences | Read, view, and comprehend different texts created to inform, influence, and/or engage audiences |

| Identify the language features of texts, including connections between print and images | Identify the text structures of familiar narrative and informative texts and their language features and visual features | Describe how similar topics and information are presented through the structure of narrative and informative texts, and identify their language features and visual features | Literal meaning and explain inferred meaning | Describe how ideas are developed, including through characters and events, and how texts reflect contexts | Explain how ideas are developed, including through characters, settings, and/or events, and how texts reflect contexts | Identify similarities and differences in how ideas are presented and developed, including through characters, settings, and/or events, and how texts reflect contexts | |

| Describe how stories are developed through characters and/or events | |||||||

| Children’s Book: Temple, K., & Temple, J. (2019). Room on Our Rock (T. R. Baynton, Illus.). Scholastic Press. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Australian Curriculum: English Content | Children’s Book Features | ITE University Coursework Topics/Concepts/Content for Discussion |

| Describe the effects of text structures and language features in literary texts when responding to and sharing opinions AC9E4LE02 | Effects of hate speech v. effects of counter-speech The book’s contrasting perspectives encourage students to examine character motivations and conflicts. | The functional model of language:

|

| Discuss how authors and illustrators make stories engaging by the way they develop character, setting, and plot tensions AC9E4LE03 | A dominant speaker addressing an in-group or the broader public to reinforce bias -v.- A speaker addressing those previously excluded, offering them welcome instead of hostility. | Topics for discussion:

|

| Examine the use of literary devices and deliberate word play in literary texts, including poetry, to shape meaning AC9E4LE04 | Imperatives “Shoo! Go Away” reinforce exclusion Repeated use of negative negations strengthens the rejection -v.- Imperatives reframed as invitation—“Make our rock your home” transforms a command to leave into a call for belonging. Inclusive language—Words like “welcome”, “our rock”, and “plenty more” signal openness rather than possession. | How cultural and linguistic factors influence students’ literacy learning E.g.,

|

| Create and edit literary texts by developing storylines, characters, and settings AC9E4LE05 | Reversible Story Challenge. Have students experiment with their own short reversible texts, following Room on Our Rock’s structure. | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Green, M. Empowering Pre-Service Teachers as Enthusiastic and Knowledgeable Reading Role Models Through Engagement in Children’s Literature. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 704. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060704

Green M. Empowering Pre-Service Teachers as Enthusiastic and Knowledgeable Reading Role Models Through Engagement in Children’s Literature. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(6):704. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060704

Chicago/Turabian StyleGreen, Mel (Mellie). 2025. "Empowering Pre-Service Teachers as Enthusiastic and Knowledgeable Reading Role Models Through Engagement in Children’s Literature" Education Sciences 15, no. 6: 704. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060704

APA StyleGreen, M. (2025). Empowering Pre-Service Teachers as Enthusiastic and Knowledgeable Reading Role Models Through Engagement in Children’s Literature. Education Sciences, 15(6), 704. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060704