Reflective Practice and Digital Technology Use in a University Context: A Qualitative Approach to Transformative Teaching

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Primary question: How do the faculty of coordinated subjects in the participating department reflect on their teaching practice with digital technologies?

- Secondary questions:

- What pedagogical configurations are reported in the reflective records of the participating faculty members?

- What types of teaching practices using digital technologies can be developed based on the faculty’s reflective practice approach?

2. Literature Review

2.1. The Role of Digital Technology in University Learning

2.2. Challenges to the Use of Digital Technology in University Teaching

2.3. Challenges to the Use of AI in University Teaching

2.4. The Role of Reflective Practice in Promoting Collaborative Academic Development

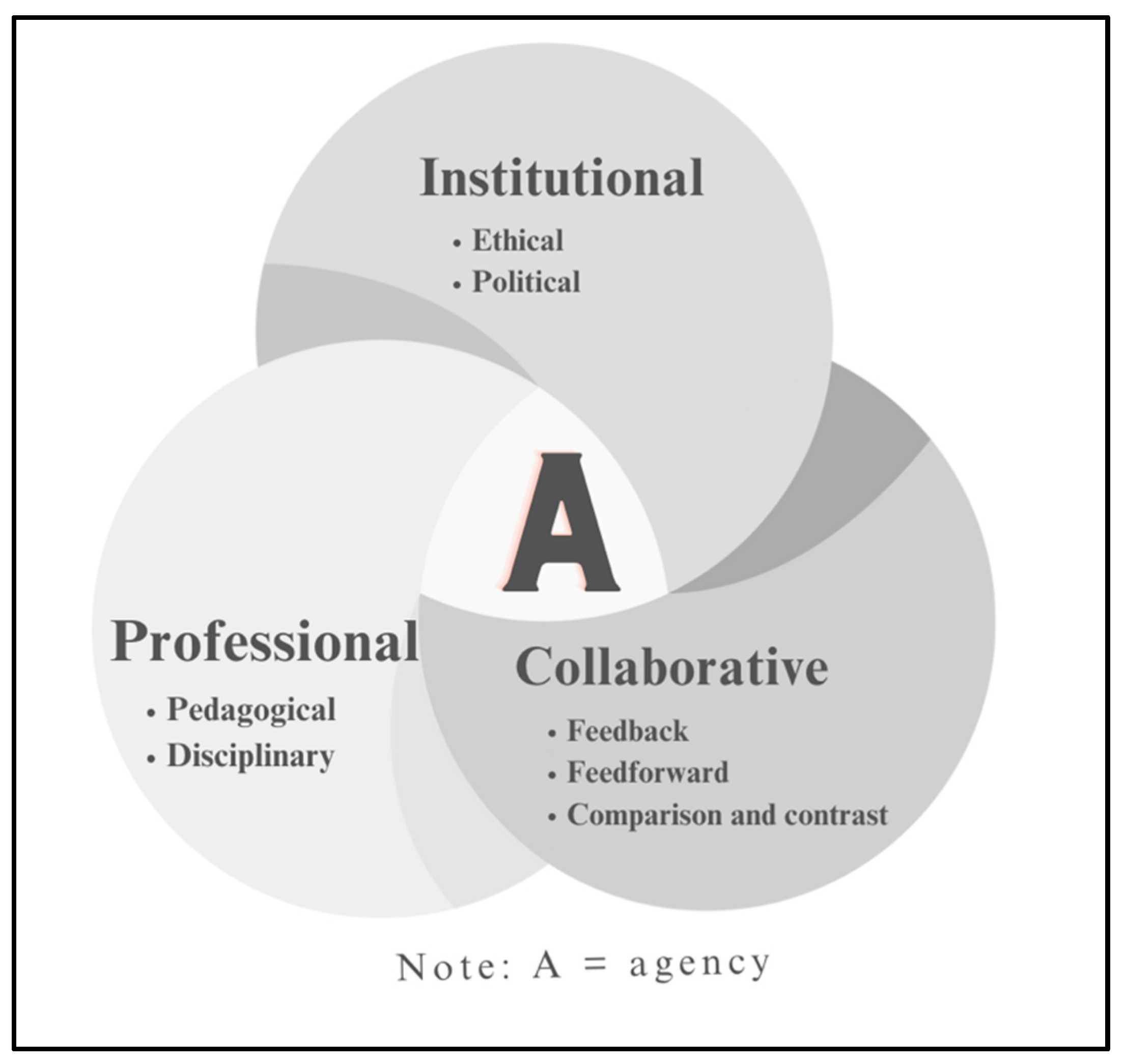

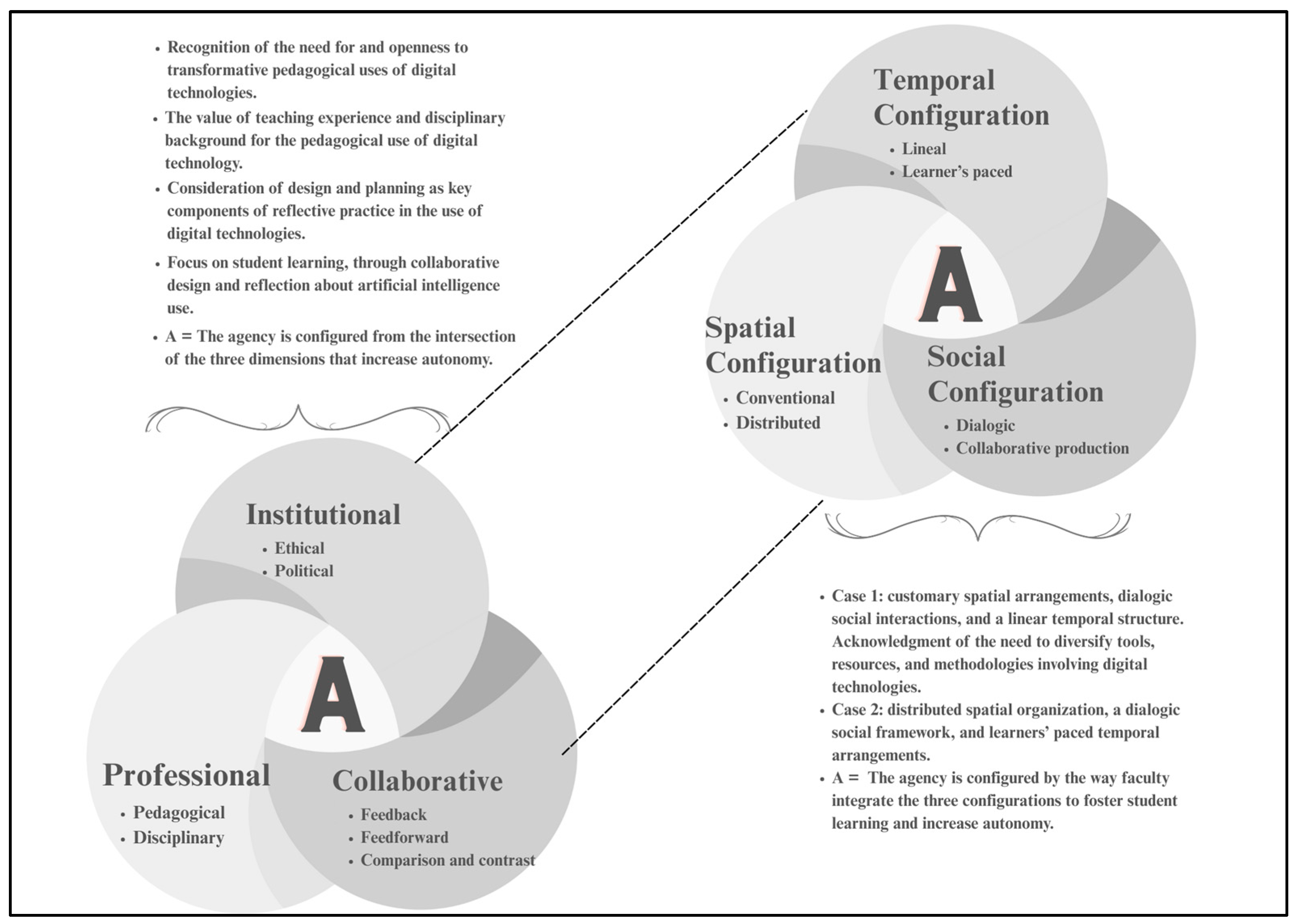

- Professional or personal: This dimension refers to an individual teacher’s ability to consider and apply their pedagogical approaches, including the unique characteristics of their discipline and the relevant pedagogical elements associated with the subject they teach.

- Collaborative: This dimension refers to engaging academic or professional peers in reflective practice. It encompasses the reception of feedback and the proposal of ideas for improvement when faced with the challenging aspects of practice to enhance the future design and implementation of their practice. It also includes comparing and contrasting one’s own practice with that of peers to promote continuous improvement.

- Institutional: This dimension pertains to integrating regulations, expectations, and conditions for the use of digital technologies in education. It embodies a political and ethical perspective, emphasizing these aspects to enhance student learning.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Sampling

- The faculty must be engaged in the designated department, specifically in a subject with established coordination, as it is taught across multiple programs within the department. This criterion ensures that they can collaboratively contribute to the design of curricula and syllabi and observe and reflect on teaching practices.

- Alternatively, educators teaching subjects with comparable attributes were invited to form a discussion group for reflection.

- Additionally, the participating faculty must regularly incorporate digital technologies in their instructional practices.

3.2. Participants’ Background

3.3. Data Collection and Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Faculty Reflections About Their Teaching Practices with Digital Technologies

“I would suggest diversifying materials to stimulate students’ learning. The teacher can design more interactive resources, such as online quizzes, among others”.(feedback provided by faculty member 4 for faculty member 1, Case 1)

“To enhance the effectiveness of PowerPoint presentations, it would be valuable to integrate a more significant use of whiteboards or other materials. This approach can help maintain students’ attention and improve their understanding of the content. Additionally, it may be valuable to explore the integration of supplementary technological tools beyond those typically found in a conventional classroom”.(feedback by faculty member 3 for faculty member 2, Case 1)

“The AI tool we designed was intended to enhance student engagement with the history of Chilean medicine by encouraging exploration and more profound comprehension of relevant topics. It offers supplementary resources and emphasizes intriguing facts about the museum’s exhibitions. We helped students craft the prompts to fulfill these objectives with specific characteristics that foster inquiry and critical thinking”.(faculty member 1, Case 2)

“The wide range of knowledge and applications that faculty member 3 demonstrates in various topics sometimes leads him to delve into aspects that, although enriching, are not always directly covered in the program syllabus. I find it difficult to express this in less than entirely positive terms, as I consider these additional contributions to be of great value”.(feedback provided by faculty member 3 for faculty member 2, Case 1)

“[The faculty member observed] effectively plans and organizes course content, uses a variety of teaching and assessment strategies”.(feedback provided by faculty member 1 for faculty member 3)

“Items evaluated:1. Knowledge and mastery of the subject: 4 points/5pts.2. Planning and organization: 3.8/5pts.3. Ability to teach: 3/5pts.4. Communication: 4.5/5pts.5. Ability to motivate and stimulate learning: 2/5pts.6. Classroom management: 3.5/5pts.7. Evaluation and feedback: 2/5pts”.(criteria for colleague observations and feedback within Case 1; also see Appendix B)

“Feedback is a common observation among students and applies to all teachers, including myself. If we don’t provide it, it is wrong; but when we provide it on an ongoing basis, it often becomes an opportunity for the student to try to raise their grade, rather than learning from the assessment. This comment is relevant to teacher 2, although I consider it a situation shared by the entire teaching team”.(feedback from faculty member 1 for faculty member 3, Case 1)

4.2. Pedagogical Configurations and Types of Teaching Practices Using Digital Technologies

“Through activities such as educational trivia, students feel challenged and motivated to learn more about topics such as historical medical instruments, advances in anesthesia and gynecology, or the implementation of technologies such as X-rays”.(faculty member 1, Case 2)

“Also, it would be valuable to integrate other technological tools, in addition to those of a conventional classroom, to increase student comprehension”.(feedback from faculty member 2 for faculty member 4, Case 1)

“The chatbot includes an interactive trivia function, allowing students to assess their knowledge of the museum’s exhibition. The questions are multiple-choice, true/false, and open-ended, all based on the uploaded documents and information on the museum’s website (…) After each question, it provides educational feedback that expands the information on the topic, motivating students to review the documents and delve deeper into the content”.(faculty member 1’s personal reflection, Case 2)

“We developed a strategy to support students on their visit to the National Museum of Medicine (www.museomedicina.cl; accessed on 2 December 2024). This activity offered the possibility of designing a customized AI chatbot as a student support tool for the museum visit, that is, serving as an educational assistant and guide for students”.(faculty member 1’s personal reflection, Case 2)

| a. “What pedagogical configurations are reported in the reflective records of the participating faculty members?” b. “What types of teaching practices using digital technologies can be developed based on the faculty’s reflective practice approach” | |

| Category | Number of Recurrences |

| 7. The faculty members focus on student learning while participating in collaborative reflection. | 5 |

| 8.Collaborative and interdisciplinary reflective endeavors foster personalized learning activities. | 6 |

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- (a)

- Institutional Structures

- (b)

- Design of Reflective Processes

- (c)

- Sustainability and Institutional Alignment

7. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| TPACK | Technology, pedagogy, and content knowledge |

| SAMR | Substitution, augmentation, modification, and redefinition |

| CFD | Continuous faculty development |

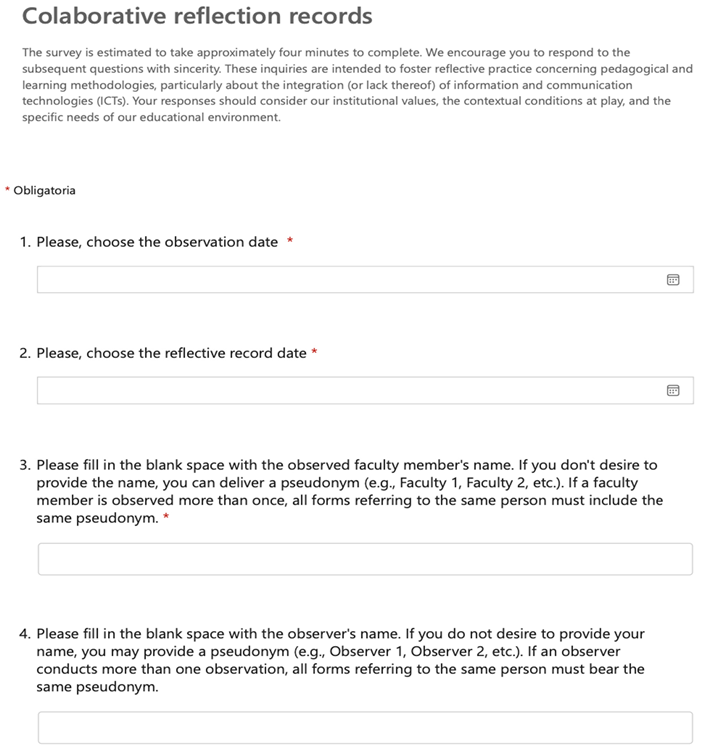

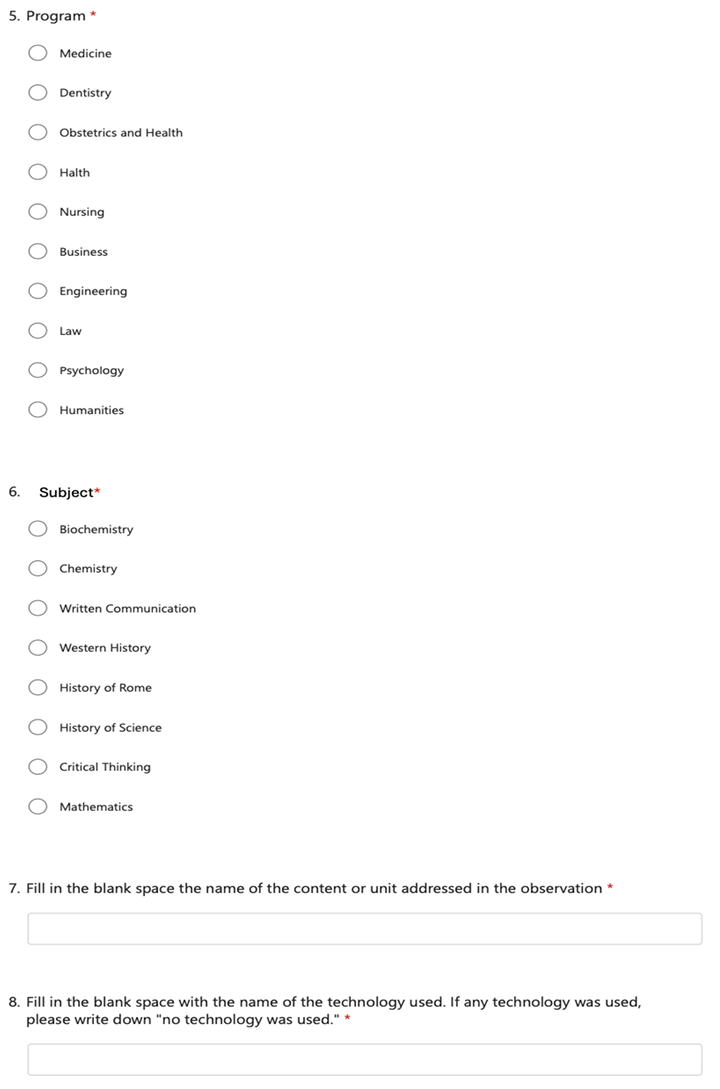

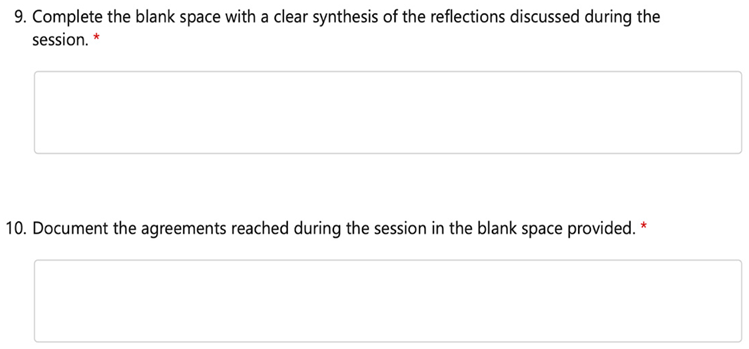

Appendix A. Institutional Reflective Record Sample

Appendix B. Case 1’s Own Reflective Instrument

| Evaluation Criteria | Excellent 5 | Good 4 | Fair 3 | Sufficient 2 | Needs Improvement 1s |

| Knowledge and Subject Mastery | Demonstrates in-depth knowledge and comprehensive understanding of the subject; uses multiple resources and tools to enrich teaching. | Demonstrates solid knowledge and adequate understanding of the subject; uses some resources and tools to support teaching. | Demonstrates basic knowledge and limited understanding of the subject; uses few resources and tools. | Demonstrates insufficient knowledge of the subject; does not use resources or tools to support teaching. | Demonstrates a total lack of knowledge and understanding of the subject; does not use any resources or tools. |

| Planning and Organization | Effectively plans and organizes course content; uses a variety of teaching and assessment strategies. | Adequately plans and organizes course content; uses some teaching and assessment strategies. | Plans and organizes course content in a basic manner; uses few teaching and assessment strategies. | Insufficiently plans and organizes course content; does not use teaching or assessment strategies. | Does not plan or organize course content; does not use teaching or assessment strategies. |

| Teaching Ability | Demonstrates exceptional teaching skills and explains complex concepts effectively. | Is a good teacher, capable of explaining concepts clearly. | Sometimes struggles to explain certain concepts. | Frequently struggles to teach and explain concepts. | Has significant difficulty teaching and explaining concepts. |

| Communication | Communicates clearly and effectively with students, fostering an environment of respect and collaboration. | Communicates adequately with students, fostering respect and collaboration. | Communicates in a limited manner, not always fostering respect and collaboration. | Communicates unclearly and inconsistently; does not foster respect and collaboration. | Does not communicate effectively; does not foster respect or collaboration. |

| Ability to Motivate and Stimulate Learning | Actively motivates and stimulates student learning; fosters active participation and collaboration in class. | Adequately motivates and stimulates student learning; encourages participation and collaboration. | Limited motivation and stimulation of student learning; fosters limited participation. | Insufficiently motivates and stimulates learning; does not foster participation or collaboration. | Does not motivate or stimulate learning; does not foster participation or collaboration. |

| Classroom Management | Effectively manages the class and creates a safe and respectful learning environment. | Effectively manages the class and creates a safe and respectful learning environment. | Adequately manages the class but could improve in fostering a safe and respectful environment. | Limited classroom management; struggles to create a safe and respectful learning environment. | Does not manage the class effectively. |

| Assessment and Feedback | Effectively assesses student progress and provides constructive feedback. | Adequately assesses progress and provides feedback, though assessment effectiveness could improve. | Provides basic assessment and feedback; needs to improve quality of feedback. | Struggles to effectively assess progress and provide constructive feedback. | Inadequate assessment of student progress; does not provide constructive feedback. |

| Comments | |||||

References

- Akram, H., Abdelrady, A. H., Al-Adwan, A. S., & Ramzan, M. (2022). Teachers’ perceptions of technology integration in teaching-learning practices: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 920317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albion, P. R., & Tondeur, J. (2018). Information and communication technology and education: Meaningful change through teacher agency. In J. Voogt, G. Knezek, R. Christensen, & K.-W. Lai (Eds.), Second handbook of information technology in primary and secondary education springer international handbooks of education. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amhag, L., Hellström, L., & Stigmar, M. (2019). Teacher educators’ use of digital tools and needs for digital competence in higher education. Journal of Digital Learning in Teacher Education, 35(4), 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, B. A. (2023). The AI literacy imperative: Empowering instructors and students. Sovorel Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bearman, M., Ryan, J., & Ajjawi, R. (2022). Discourses of artificial intelligence in higher education: A critical literature review. Higher Education, 86, 369–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, H. J. (2000). Findings from the teaching, learning, and computing survey: Is larry cuban right? Education Policy Analysis Archives, 8(51), 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleakley. (2006). From reflective practice to holistic reflexivity. Studies in Higher Education, 24, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdan, R., & Biklen, S. (2006). Qualitative research for education. An introduction to theories and methods. Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Bond, M., Khorsavi, H., Da Laat, M., Bergdhal, N., Negrea, V., Oxley, E., Pham, P., Wan Chong, S., & Siemens, G. (2024). A meta systematic review of artificial intelligence in higher education: A call for increased ethics, collaboration, and rigour. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 21(4), 9–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Bruggeman, B., Garone, A., Struyven, K., Pynoo, B., & Toundeur, J. (2022). Exploring university teachers’ online education during COVID-19: Tensions between enthusiasm and stress. Computers & Education Open, 3, 10095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckingham, D. (2019). The media education manifesto. Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z., & Chen, R. (2022). Exploring the key influencing factors on teachers’ reflective practice skill for sustainable learning: A mixed methods study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(18), 11630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claro, M., Salinas, A., Cabello-Hutt, T., San Martín, E., Preiss, D., Valenzuela, S., & Jara, I. (2018). Teaching in a Digital Environment (TIDE): Defining and measuring teachers’ capacity to develop students’ digital information and communication skills. Computers & Education, 121, 162–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colomer, J., Serra, T., Cañabate, D., & Bubnys, R. (2020). Reflective learning in higher education: Active methodologies for transformative practices. Sustainability, 12(9), 3827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, H., & Burke, D. (2020). Mobile learning and pedagogical opportunities. Computers & Education, 156, 103945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuban, L. (2001). Oversold and underused: Computers in the classroom. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Damşa, C., Langford, M., Uehara, D., & Scherer, R. (2021). Teachers’ agency and online education in times of crisis. Computers in Human Behavior, 121, 106793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demzky, D., Liu, J., Hill, H. C., & Piech, D. J. C. (2024). Can automated feedback improve teachers’ uptake of student ideas? Evidence from a randomized controlled trial in a large-scale online course. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 46(3), 483–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, J. (1910). How we think. D.C. Heath. [Google Scholar]

- Dourish, P. (2017). The stuff of bits. An essay on the materialities of information. MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Eicken, H., Danielsen, F., Sam, J.-M., Fidel, M., Samarakou, N., Poulsen, M. K., Lee, O. A., Spellman, K. V., Iversen, L., Pulsifer, P., & Enghoff, M. (2021). Connecting top-down and bottom-up approaches in environmental observing. BioScience, 71(5), 467–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elder, L., & Paul, R. (2005). Asking essential questions. The Foundation of Critical Thinking. Available online: https://www.criticalthinking.org/files/SAM-Questions2005.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Fernández-Batanero, J. M., Román-Graván, P., Montenegro-Rueda, M., López-Meneses, E., & Fernández-Cerero, J. (2021). Digital teaching competence in higher education: A systematic review. Education Sciences, 11(11), 689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, P. (1998). Pedagogy of freedom. Ethics, democracy and civic courage. Littlefield Publichers. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. (2005). Pedagogy of indignation. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. (2014). Pedagogy of commitment. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ibieta, A., Hinostroza, J. E., Labbé, C., & Claro, M. (2017). The role of the Internet in teachers’ professional practice: Activities and factors associated with teacher use of ICT inside and outside the classroom. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 26(4), 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilomäki, L., & Lakkala, M. (2018). Digital technology and practices for school improvement: Innovative digital school model. Research and Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning, 13, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaarakainen, M. T., & Saikkonen, L. (2021). Multilevel analysis of the educational use of technology: Quantity and versatility of digital technology usage in Finnish basic education schools. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 37(4), 953–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamoun, F., El Ayeb, W., Jabri, I., Sifi, S., & Iqbal, F. (2024). Exploring students’ and faculty’s knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions towards ChatGPT: A cross-sectional empirical study. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 23(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, E., & Laurillard, D. (2024). Online learning futures. An evidence-based vision for global professional collaboration and sustainability. Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Koehler, M. J., Mishra, P., & Cain, W. (2017). What is TPACK? Journal of Education, 193(3), 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurillard, D. (2012). Teaching as a design science. Building pedagogical patterns for learning and technology. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Laurillard, D., Kennedy, E. T., Charlton, P., Wild, J., & Dimakopoulos, D. (2018). Using technology to develop teachers as designers of TEL: Evaluating the learning designer. British Journal of Educational Technology, 49(6), 1044–1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavonen, J. (2020). Curriculum and teacher education reforms in Finland that support the development of competences for the twenty-first century. In F. M. Reimers (Ed.), Audacious education purposes: How governments transform the goals of education systems (pp. 65–80). Springer Open. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, C.-P., Zhao, Y., Tondeur, J., Chai, C.-S., & Tsai, C.-C. (2013). Bridging the gap: Technology trends and use of technology in schools. Educational Technology & Society, 16(2), 59–68. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/jeductechsoci.16.2.59 (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Livingstone, S. (2012). Critical reflections on the benefits of ICT in education. Oxford Review of Education, 38(1), 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lomos, C., Luyten, J. W., & Tieck, S. (2023). Implementing ICT in classroom practice: What else matters besides the ICT infrastructure? Large-Scale Assessments in Education, 11, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughran, J. (2002). Effective reflective practice: In search of meaning in learning about teaching. Journal of Teacher Education, 53(1), 33–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luckin, R. (Ed.). (2018). Enhancing learning and teaching with technology. What the research says. UCL Institute of Education Press. [Google Scholar]

- Luckin, R., Clark, W., Garnett, F., Withworth, A., Akass, J., Cook, J., Day, P., Ecclesfield, N., Hamilton, T., & Robertson, J. (2011). Learner generated contexts: A framework to support the effective use of technology to support learning. In M. Lee, & C. McLoughlin (Eds.), Web 2.0-based E-learning: Applying social informatics for tertiary teaching (pp. 70–84). IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J., Chen, B., & Liu, J. C. (2024). Generative artificial intelligence in education and its implications for assessment. TechTrends, 68, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, N. G. (2012). Reflective classroom practice for effective classroom instruction. International Education Studies, 5(3), 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michos, K., Hernández-Leo, D., & Albo, L. (2018). Teacher-led inquiry in technology-supported school communities. British Journal of Educational Technology, 49(6), 1077–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M., Rashid, R. A., & Alqaryouti, M. H. (2022). Conceptualizing the complexity of reflective practice in education. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1008234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero-Mesa, L., Fraga-Varela, F., Vila-Couñago, E., & Rodríguez-Groba, A. (2023). Digital technology and teacher professional development: Challenges and contradictions in compulsory education. Education Sciences, 13(10), 1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Msafiri, M. M., Kangwa, D., & Cai, L. (2023). A systematic literature review of ICT integration in secondary education: What works, what does not, and what next? Discover Education, 2(44), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoa Echaurren, Á. (2022). Towards a model of ICT reflexive practice: Investigating teachers’ user-generated contexts and agency in a K-12 chilean school [Doctoral dissertation, UCL (University College London)]. Available online: https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10152943/ (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Novoa-Echaurren, Á. (2024). Teacher agency in the pedagogical uses of ICT: A holistic perspective emanating from reflexive practice. Education Sciences, 14(3), 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novoa-Echaurren, Á., Canales-Tapia, A., & Molin-Karakoç, L. (2025). Pedagogical uses of ICT in Finnish and Chilean schools: A systematic review. Contemporary Educational Technology, 17(1), ep561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osterman, K. F., & Kottkamp, R. (1993). Reflective practice for educators: Improving schooling through professional development. Corwin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ostinelli, G., & Crescentini, A. (2021). Policy, culture and practice in teacher professional development in five European countries: A comparative analysis. Professional Development in Education, 50(1), 74–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrotta, C., & Selwyn, N. (2019). Deep learning goes to school: Toward a relational understanding of AI in education. Learning, Media and Technology, 45(3), 251–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philipsen, B., Tondeur, J., Pynoo, B., Vanslambrouck, S., & Zhu, C. (2019). Examining lived experiences in a professional development program for online teaching: A hermeneutic phenomenological approach. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 35(5), 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popenici, S. A. D., & Kerr, S. (2017). Exploring the impact of artificial intelligence on teaching and learning in higher education. Research and Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning, 12, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Potter, J., & McDougall, J. (2017). Digital media, culture and education: Theorising third space literacies. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puentedura, R. (2015). Learning, technology, and the SAMR model: Goals, processes, and practice. Available online: http://www.hippasus.com/rrpweblog/archives/2014/06/29/LearningTechnologySAMRModel.pdf (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Rivera-Vargas, P., & Cobo, C. (2020). Digital learning: Distraction or default for the future. Digital Education Review, 37. Available online: https://revistes.ub.edu/index.php/der/article/view/31813/pdf (accessed on 2 December 2024).

- Ruggiero, D., & Mong, C. J. (2015). The teacher technology integration experience: Practice and reflection in the classroom. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 14, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabariego Puig, M. (2019). El proceso de investigación. In R. B. Alzina (Coord.), Metodología de la investigación educativa (pp. 123–160). Arco. [Google Scholar]

- Schön, D. A. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Sellars, M. (2012). Teachers and change: The role of reflective practice. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 55, 461–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selwyn, N. (2019). Should robots replace teachers? AI and the future of education. Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Selwyn, N. (2022). Education and technology: Key issues and debates. Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Smuha, N. (2023). Pitfalls and pathways for trustworthy artificial intelligence in education. In W. Y. Holmes, & K. Porayska-Pompsta (Eds.), The ethics of artificial intelligence in education. Practices, challenges and debates (pp. 113–146). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosa-Díaz, M. J., Sierra-Daza, M. C., Arriazu-Muñoz, R., Llamas-Salguero, F., & Durán-Rodríguez, N. (2022). EdTech integration framework in schools: Systematic review of the literature. Frontiers in Education, 7, 895042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tallvid, M. (2016). Understanding teachers’ reluctance to the pedagogical use of ICT in the 1:1 classroom. Education and Information Technology, 21, 503–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S., Bodman, S., & Morris, H. (2015). Politics, policy and teacher agency. In D. Wyse, D. Davis, P. R. Jones, & S. Rogers (Eds.), Exploring education and childhood (pp. 56–70). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. (2024). Global education monitoring report (GEM), 2023: Technology in education: A tool on whose terms? UNESCO. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Manen, M. (2006). On the epistemology of reflective practice. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 1(1), 33–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vires, J. A., Visscher, A. J., & Schildkamp, K. (2024). A learning theory-based exploratory analysis of teacher professional development interventions for formative assessment. Review of Education, 12, e70009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, B., Bayne, S., & Shay, S. (2020a). The datafication of teaching in higher education: Critical issues and perspectives. Teaching in Higher Education, 25(4), 351–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, B., Eynon, R., & Potter, J. (2020b). Pandemic politics, pedagogies and practices: Digital technologies and distance education during the coronavirus emergency. Learning, Media and Technology, 45(2), 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zawacki-Richter, O., Marín, V. I., Bond, M., & Gouverneur, F. (2019). Systematic review of research on artificial intelligence applications in higher education—Where are the educators? International Journal in Higher Education, 16(39), 2–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Case N° | Thematic Area | Course | Number of Faculty Members | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sciences | Biochemistry | 2 | 20 |

| 1 | Chemistry | 3 | 30 | |

| 1 | Biology | 1 | 10 | |

| 2 | Humanities | History of Science | 2 | 40 |

| 2 | Western History | 2 | ||

| Total | 10 | 43 |

| “Primary question: How do the faculty of coordinated subjects in the participating department reflect on their teaching practice with digital technologies?” | |

| Category | Number of Recurrences |

| 1. The faculty members recognize the need for and are open to transformative pedagogical uses of digital technologies. | 2 |

| 2. The faculty member’s reflective records revealed varied applications of digital technology in their teaching. | 7 |

| 3. The faculty member values teaching experience and disciplinary background for the pedagogical use of digital technology. | 8 |

| 4. The faculty member values design and planning as key components of reflective practice concerning the use of digital technologies. | 4 |

| 5. Reflection enables the faculty member to adapt decision-making to their situational needs, increasing collaborative agency. | 7 |

| 6. Reflexivity is a crucial mechanism for the continuous improvement of educational quality. | 21 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Novoa-Echaurren, Á.; Pavez, I.; Anabalón, M.E. Reflective Practice and Digital Technology Use in a University Context: A Qualitative Approach to Transformative Teaching. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 643. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060643

Novoa-Echaurren Á, Pavez I, Anabalón ME. Reflective Practice and Digital Technology Use in a University Context: A Qualitative Approach to Transformative Teaching. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(6):643. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060643

Chicago/Turabian StyleNovoa-Echaurren, Ángela, Isabel Pavez, and Marco Esteban Anabalón. 2025. "Reflective Practice and Digital Technology Use in a University Context: A Qualitative Approach to Transformative Teaching" Education Sciences 15, no. 6: 643. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060643

APA StyleNovoa-Echaurren, Á., Pavez, I., & Anabalón, M. E. (2025). Reflective Practice and Digital Technology Use in a University Context: A Qualitative Approach to Transformative Teaching. Education Sciences, 15(6), 643. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15060643