1. Introduction

Bullying is a social problem that has persisted for as long as humans have roamed the earth, and it can occur in almost every stage of human existence. We may even dare to say that it is part of our nature. Only in recent years has it become an international public health concern (

Rivara & Menestrel, 2016). UNESCO research indicates that one-third of the world’s children experience bullying (

UNESCO, 2019).

Bullying refers to repeated aggressive behavior toward a goal that harms another person in the context of a specific power imbalance (

Gredler, 2003). This definition stood the test of time, as it remains the most prominent one in the field of research on bullying. It provided the foundation for developing the Olveus Bullying/Victimization Questionnaire (OBVQ). The OBVQ has been used to analyze the prevalence of bullying among thousands of adolescents all around the world (

Currie et al., 2012). What we can see from this definition, starting from its keywords, is the repetitive nature of bullying, the power imbalance between bully and victim, and the intentionality behind the actions.

Therefore, bullying can take various forms, including physical aggression, verbal harassment, social exclusion, and cyberbullying, each with its own particularity and specific implications. None of the forms of bullying can be considered as easier/less harmful than the others: for example, although on the surface social exclusion may appear to be an easier form of bullying than physical harassment, its long-term effects can be as negative as those of physical harassment. More recent research, however, argues that bullying can also occur for entertainment purposes or because of teasing and diminishing of reputation, which does not involve a clear intention to harm (

Kerr et al., 2016).

Our study focuses on the middle school years, during which this phenomenon remains as one of the most common forms of violence in the peer context. While comprehensive research has been conducted, and the literature on this subject is extensive, a more refined understanding of its prevalence, manifestation, and effects within specific cultural structures and contexts remains crucial.

When the levels of cyberbullying increased, we had to find solutions and be creative to protect students and their parents from the potentially harmful and devastating effects of this phenomenon. It appears that bullying can erode the fragile tissue of our societal structures and spheres. Once society evolves, bullying tries to take on another, more evolved and maybe more harmful, form.

The present research is crucial in understanding how bullying occurs in Romanian middle schools. We aimed to determine the prevalence of bullying and its effects on students and their well-being from a sociodemographic perspective.

Research on bullying started almost fifty years ago. The phenomenon was defined back then as “repetitive, intentional aggressive acts” (

Espelage & Swearer, 2003;

Gredler, 2003). As research evolved, we found that bullying cannot simply be an isolated act of aggression. Currently, savants view it as a manifestation of power dynamics that are influenced by social, psychological, and cultural dimensions.

Bullying endangers children’s rights, including the right to education. It represents a higher risk factor for vulnerable groups such as children with disabilities, refugees, children affected by migration, minorities, or children that simply differ from their peers.

Bullying can occur in a multitude of places and social contexts: anywhere from the internet to school classrooms. To fully comprehend the complexity of bullying, we have to understand that it is a multi-disciplinary phenomenon. Different research domains, such as sociology, pedagogy, psychology, and law, have analyzed it from various perspectives.

In sociology, Durkheim’s (

Pope, 1975) functionalism offers a framework for understanding how social norms and structures help maintain social order, even in the deviating presence of bullying.

Bandura’s (

2001) Social Learning Theory emphasizes the importance of learning by observing and modeling behaviors.

Becker (

1963) developed the Social Labeling Theory, which states that societal labeling shapes an individual’s identity and behaviors. Psychology reveals, through Dollard’s (

Dollard et al., 1939) theory, that frustration being experienced by students, such as academic decline or hardships, can lead to aggression.

In this paper, however, we will mainly focus on the sociological and psycho-pedagogical perspectives. Looking at the existing literature, we find that the theoretical explanations of bullying can be separated into three main categories. The first is the quality and character of one’s self, which cannot be changed—“the nature of the beast”. The second is the individual’s environment. This has social, cultural, biological, and educational implications (

Anderson, 2022). The third is the interaction between the above.

The most often used definition was developed by Olweus (

Gredler, 2003), who stated that bullying is a repeated and deliberate negative act performed by a person or group of people who are perceived to have a higher status or strength than the victim.

Later, researchers defined bullying in a similar manner as an unwanted, repeated, and aggressive behavior that is intentional and takes place within the context of peer relationships (

Hicks et al., 2018). School should be a safe learning environment for children, ideally without the aggression that bullying implies. Aggression refers to the human expression of wanting to harm or control another.

During the 1970s, Olweus coordinated the first studies on bullying and developed one of the first school bullying prevention programs, known as the “Olweus Bullying Prevention Program (OBPP)”, a program that is considered highly effective and is still used in schools around the world to prevent and combat bullying (

Olweus, 1973).

This program is based on the principle that bullying can be prevented and reduced through changes at the school level by cultivating harmonious relationships between pupils and is based on the following principles: awareness and involvement of the whole school community (pupils, teachers, leaders, and parents), school-wide interventions, and continuous training of teachers in the identification and management of bullying behaviors (

Gredler, 2003).

The implementation of the Olweus Program has proven to be effective in many cases, contributing to the decrease in bullying in schools and having a positive effect on the school climate and pupils’ well-being. According to a study conducted by one study (

Ttofi & Farrington, 2011) on 44 different prevention programs, the ones driven by the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program (OBPP) seem the most effective. In addition, the Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire (OBVQ) is the most used bullying self-report measure across the globe (

Cikili-Uytun et al., 2023).

Hicks et al. (

2018) stated that there are two models and four types of bullying. The models refer to direct and indirect bullying. Naturally, direct bullying happens in the victim’s presence, while indirect bullying occurs without confrontation. The victim is therefore targeted “through indirect means such as the spreading of rumors” (

Hicks et al., 2018).

In addition, the four types of bullying are physical, verbal, relational, and damage to property. One study (

Thornberg & Delby, 2019) distinguished between intentional and unintentional bullying. Malign bullying is deliberate harm-inflicting behavior. Non-malignant bullying involves actions that unintentionally cause distress to the victim due to the bully’s lack of awareness of the negative impact.

Maunder and Crafter (

2018) explored an important approach to research on bullying. In their paper, they adopted a sociocultural perspective that allowed them to analyze predefined variables such as bullying behaviors and compare differences between predefined groups such as different genders, different age groups, students, teachers, etc. This is especially important when we observe a trend in the existing literature that adopts a more epistemological view. These studies state that it is hard to define bullying as an isolated phenomenon, but they do not offer a comprehensive understanding of bullying in the institutional and cultural contexts. That is what our study aimed to achieve.

We know from

Bandura’s (

2001) social cognitive theory that an individual’s attitude influences their individual view of their experiences in life significantly. Therefore, how students perceive their school climate is critical (

Bear et al., 2014). Interventions that aim to improve students’ perceptions of school seem to be most effective when they are focusing on individuals who face risk conditions such as bullying. This is especially important when designing programs that aim to promote a healthy learning environment and reduce bullying or other negative behaviors in schools.

A study (

UNESCO, 2019) showed that bullying can affect the victim’s physical and mental health, having been associated with low levels of self-esteem, loneliness, physical health complications, and psychological distress.

Bullying negatively affects not only the victims but, on a larger scale, the entire peer group (

Nickerson, 2019).

Erginoz et al. (

2013) showed in their study that the school climate and students’ perceptions of school are strongly associated with bullying.

The stress of academic performance has proven to have an equal impact on various aspects of mental health. In addition, students who are victims of bullying are twice as likely to engage in self-harm compared with their peers who have not been bullied (

John et al., 2023).

In the United States, one study (

Nguyen et al., 2023) found a significant correlation between bullying and an increased risk of depressive symptoms and suicidality among students. In addition, they also identified some protective factors, such as sufficient sleep and physical activity.

Bayer et al. (

2018) found that poor mental health in children can make them more vulnerable to bullying. Some say that a bullying event can be managed by social support and a strong character (

Vrajitoru et al., 2024).

1.1. On an International Scale

Research shows that bullying tops out during middle school (

Kennedy, 2020). In Australia, bullying remains a significant issue, with an alarmingly high level of bullying among Australian middle school students (

Kelly et al., 2019). The study suggests the implementation of targeted intervention programs, especially for high-risk students, who can be identified based on their personality profiles.

Garmy et al. (

2018) stated that, in Iceland, the situation is quite similar to the US and Australia. Despite anti-bullying initiatives such as the Owelus program, bullying remains a significant challenge, with 5.5% of Icelandic middle school students reporting being bullied at least twice per month. Their study also revealed that socioeconomic status has no significant correlation to bullying, but family structure and cultural background do. They identified a gap in the literature, and further research should focus on these sociodemographic factors. This is what our study aimed to analyze.

Sansait et al. (

2023) revealed that snobbery, rumors, and physical bullying are the most present in the Philippines among students. In their study, they analyzed the differences between private and public schools. They found that public school students received more extensive support than their private school colleagues. They suggested analyzing the wider context of a student’s environment, such as family and social variables.

Kennedy (

2020) also confirmed this, stating that there is no upward trend in the US regarding direct bullying. However, bullying victimization has declined among boys, while girls reported an increased level of bullying.

In contrast,

Li et al. (

2020) found that bullying in Chinese rural middle schools is much higher than the global average (50.6% to 32%). In addition, they found that boys reported higher rates of bullying and low levels of academic performance.

In Indonesia, we see a rate that is closer to the global average, with 24.4% of students reporting being bullied in school (

Devi & Yulianandra, 2023).

The inconsistencies in the research results regarding bullying underscore the need for caution when generalizing trends. Bullying is a complex and context-specific phenomenon demanding analysis within particular sociocultural frameworks. A nuanced understanding, achieved by considering these contexts, allows for more effective interventions that are tailored to students’ specific needs and ultimately contribute to healthier learning environments.

1.2. On a National Scale

In Romania, the prevalence of bullying is alarmingly high (

Robayo-Abril & Rude, 2023).

Rus et al. (

2024) conducted a study in Constanța. They emphasized the complexity of the phenomenon, which is influenced by various characteristics such as aggression, impulsivity, parenting style, and domestic violence.

Mureșan (

2020) studied Romanian middle school students in Cluj. He found that verbal aggression (24.39%), repetitive irony (20.73%), and physical aggression (18.29%) were the most prevalent forms of bullying being reported.

According to a report from the World Health Organization (

World Health Organization, 2014), Romania is in a whopping 3rd place in Europe among 42 countries in terms of the prevalence of bullying.

Tomescu (

2024) offered extensive data on the prevalence of bullying in various European countries. He found that Eastern European countries such as Lithuania, Bulgaria, and Romania report significantly higher rates of bullying than Western European countries such as Finland or Norway. He also states that bullying is a multi-faceted phenomenon, and various socioeconomic factors can influence it. He identified a need for culturally sensitive strategies in bullying prevention.

The research rationale for this study originates from the need to address and understand the prevalent issue of bullying within the Romanian educational system (

Bularca et al., 2021). Despite the extensive literature on bullying in various contexts such as sports, adulthood, and elementary schools (

Husky et al., 2020;

Melinte et al., 2023;

Nichifor et al., 2023), there is a lack of recent comprehensive research focused on the prevalence, manifestation, and effects of bullying, specifically within Romanian middle schools.

Some other small-scale studies have been elaborated on combating bullying (

Vrajitoru et al., 2024). In addition, research has been performed on forms of bullying (

Mureșan, 2020) and the social-cognitive aspects of bullying (

Rus et al., 2024), but not many studies have been conducted in recent years on specific areas of the country to determine the problems and tendencies, come up with useful solutions, and create a harmonious school environment. Bullying in school remains, therefore, a major issue. As we explored the existing literature, it became clear that bullying needs to be addressed locally, culturally, and specifically (

Andrews et al., 2023). Bullying is not an isolated phenomenon; it can vary based on multiple social and contextual factors, and it should be treated accordingly. Most teachers in Romania are not specifically trained to acquire the skills necessary to combat bullying (

Diac & Grădinariu, 2022).

The most impactful study was published in 2016 by the Save the Children Organization (

Grădinaru et al., 2016). It provides a detailed analysis of this phenomenon in Romania, providing valuable data on the frequency, forms, and consequences of bullying. The study combined qualitative and quantitative methods to capture the complexity of the bullying phenomenon.

The research assessed the bullying phenomenon through three dimensions: bully, victim, and witness. The main indicators used in the study were exclusion from the group, humiliation, destruction of others’ property, and physical violence.

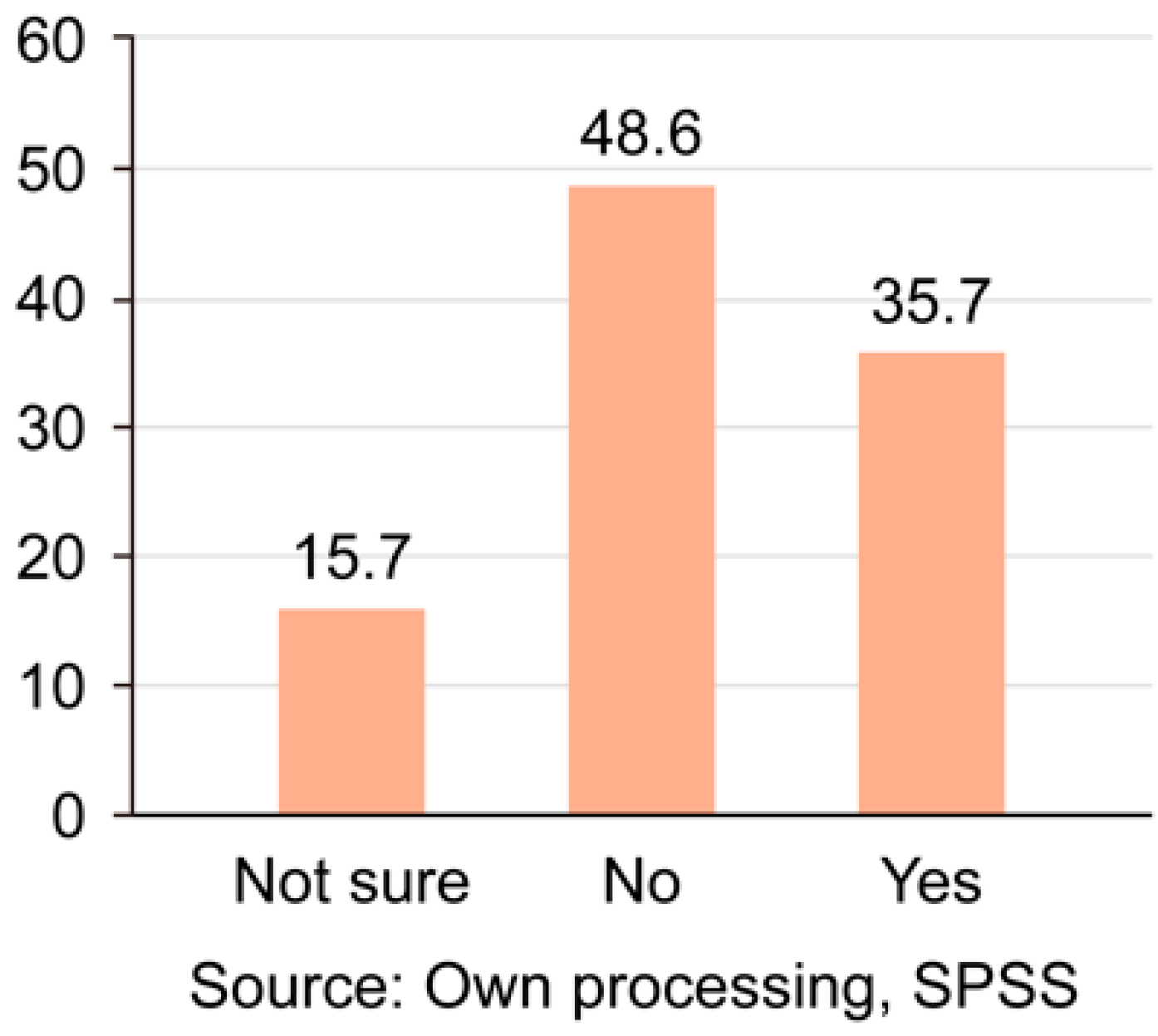

The results show that “the notoriety of the term bullying is low”, as many children and parents are not familiar with it or its implications; thus, “48% of children are familiar with the term bullying, and of these, 35% have obtained information from the internet and 30% from television” (p. 29).

At the same time, an alarming frequency of bullying incidents has been found, with significant implications for the emotional state and behavior of victims (

Grădinaru et al., 2016, pp. 29–34).

Given the high prevalence of bullying reported in Romania, as highlighted by previous studies, it is necessary to delve deeper into this phenomenon to develop targeted interventions and policies that promote a safe and school environment for all students.

Furthermore, the existing research landscape in Romania indicates a high prevalence of bullying, ranking the country among the top in Europe in terms of bullying rates. This underscores the urgency and significance of conducting localized studies to uncover the unique sociodemographic factors influencing bullying behaviors in Romanian middle schools. By exploring the complexities of bullying within the Romanian cultural and educational context, this research aims to provide insights for preventing and addressing bullying effectively.

Our research offers recommendations for policymakers and teachers to determine what aspects of the school environment and policies need to be changed, introduced, and treated to promote a positive learning environment.

The objective of our study was to determine the prevalence of bullying and its effects on students and their well-being from a sociodemographic perspective. We, the authors, would like to encourage similar research to be continuously carried out in Romania. We offer insights into understanding the complexity of bullying in the Romanian educational system with a case study in the Craiovean Region.

Based on the objective and the literature review, we identified the following hypotheses for our research:

H1. Boys will report higher rates of bullying than girls.

H2. Students with lower academic scores are more likely to be victims of bullying.

H3. Students with strong social support are less likely to become victims of bullying.

H4. The more students are victims of bullying, the lower their academic performance and emotional state will be.

2. Materials and Methods

We designed our study to be quantitative and aimed to investigate the phenomenon of bullying in middle schools in Craiova Municipality, Romania. Because our study’s design was descriptive, we were able to perform a more detailed analysis of bullying prevalence and correlations among school students. This study was conducted in 2023 and involved a sample of different middle school students from the specified area, thus ensuring representativeness.

2.1. Data Collection Method and Sample

The targeted population of this study was middle school students (fifth, sixth, seventh, and eighth graders) from the municipality of Craiova, Romania. The sampling technique we used to carry out our research was stratified convenience sampling to ensure that the results of our research are representative of middle school students in the Craiova Municipality. To respect this stratification, when we proportionally selected the students to answer our questionnaire, we selected them randomly (of different genders, from different classes, and from different socioeconomic situations). We recruited eight schools for our study based on the data we obtained from the Craiovean entity that administrates all educational institutions. Schools were selected randomly based on their results (the sample included both higher- and lower-performing schools), proximity (we selected both central and peripheric schools from Craiova Municipality), and size (we opted for smaller and bigger middle schools from the area).

Thus, we could ensure the demographic diversity of participants. The questionnaires were given in person in different schools in the municipality, both in the central area and the outskirts. In total, 673 questionnaires were completed, with an equal distribution of gender and age. This way, our research becomes more nuanced by analyzing the background of students, potential aggressors, and victims. We would like to encourage similar research to be carried out in Romania. Through this study, we offer a valuable starting point for understanding the complexity of bullying in the Romanian educational system.

The questionnaires were administered by researchers. In addition, we would like to highlight that, before data collection, informed consent was obtained from all participants and their parents. Pupils were informed that participation was entirely voluntary. All responses were anonymous, and no personally identifiable information (names, addresses, and school names) was collected.

2.2. Instruments

For data collection, we used a structured questionnaire based on the Owelus Victimization of Bullying Questionnaire and the instrument used by the “Save the Children” organization from Romania from the research entitled “Bullying among children. National sociological study” (

Grădinaru et al., 2016). The questionnaire has been validated on a national level.

Some examples of questions from our adapted questionnaire can be found below:

- -

Have you ever observed a classmate being placed in an uncomfortable situation or subjected to unpleasant behaviors by other students? If so, did you feel comfortable intervening or reporting the situation?

- -

How do you consider that the bullying incident affected your relationship with school and learning?

- -

Have you ever been involved in a bullying incident at your school?

- -

Have you ever been involved in a cyberbullying incident or witnessed one?

- -

If you had a personal experience or witnessed bullying, did you feel supported by the teaching staff or the school counselor?

- -

How do you think a victim of bullying feels?

Because of the phenomenon’s complex and nuanced nature, the questionnaire starts by defining bullying to exclude confusion with other similar concepts. Then, students are asked if they have been involved in a bullying incident or have seen others being bullied. Next, students are asked about the specific bullying behaviors that they experienced, such as sexual teasing, threats, being called names, and physical aggression. The questionnaire also addresses observational bullying (the role of the witness).

It includes both open-ended and closed questions, as well as questions with multiple answers and evaluation scales to comprehensively understand students’ perceptions of bullying. In addition, we wanted to analyze their personal experiences with bullying. Our questionnaire was tested in a pilot study, where we obtained a value of α = 0.85 for the Cronbach Coefficient.

2.3. Ethical Considerations

We want to note that informed consent has been obtained from the institution’s coordinator regarding the questionnaire’s application. All participants understood the purpose of the study, and each respondent took part in the study voluntarily, with the possibility to withdraw at any moment.

We did not collect personal data, such as name, email address, phone number, or any other information that could identify the minor’s identity. We have used age-appropriate formulations when designing our survey, questions that ensure a good understanding of the content displayed.

We have considered a well-defined and well-suited approach based on the children’s age, cognitive abilities, and the stage of their development. In addition, the ethics committee of the Faculty of Sociology and Communication in Brașov has approved our study.

The researchers initially discussed the project with the principal and identified specific survey administration dates. Questionnaires were given during coordination classes (they are held once a week in every school in Romania, where pupils are usually asked about school activities, administrative instruction, informative classes, training, events, and issue-solving). The teacher was absent during the class to ensure a calm, safe, and pressure-free environment for students to respond.

2.4. Data Collection and Analysis

The data collection stage included distributing the questionnaires and making sure that we respected each participant’s identity according to GDPR. All collected data were treated in this manner. The collected data were analyzed and processed using IBM SPSS, version 23. For the data analysis, we performed various statistical tests to analyze the collected data and better understand the phenomenon of bullying in the educational environment, including the ANOVA test, which was used to compare the differences in attitudes and perceptions regarding bullying between different groups of students, classified by criteria such as gender or class.

Also, for some questions, we calculated the Pearson correlation coefficient to verify whether there was a relationship between some variables, such as the connection between students’ self-esteem and students’ experiences of being victims of bullying. These statistical analyses were useful not only for testing the hypotheses of our research but also for identifying the factors that contribute to the prevalence and severity of the bullying phenomenon, as well as for providing evidence-based recommendations for possible intervention plans that can be outlined at the level of schools or school inspectorates.

In addition to ANOVA tests and Pearson correlations, we also used the Chi-square test to examine the relationship between certain variables, such as students’ gender or level of study and the types of bullying behaviors reported.

The Chi-square test allowed us, for example, to observe whether there is a significant link between gender and the prevalence of certain forms of bullying, such as verbal harassment or social exclusion, and to conclude whether for each of these types of bullying girls or, conversely, boys are more likely to be the victims.

Our study was conducted using ethical academic principles, including asking for permission to use the collected data and informing all participants about the study. Our project was designed to minimize the risk of possible harmful effects on participants. Therefore, all students were thoroughly informed of the study’s nature, aims, and data usage. Our research has been approved by the Faculty of Sociology and Communication Ethics Committee at the Transylvanian University of Brașov.

Data collection started in May 2023 and ended in June 2023. Participants included middle school students from the municipality of Craiova. Data collection was conducted using questionnaires and standardized methods to ensure the validity and comparability of our results. The study aimed to understand the complex phenomenon of bullying in Craiova, its prevalence, and its effects on students. In addition, it aimed to encourage efficient prevention and intervention programs.

Preliminary results revealed a significant prevalence of bullying. However, it did not significantly impact the victims’ and the aggressors’ academic performance, as we initially thought. Observational bullying, however, was linked to academic performance. This means that students who were witnesses to bullying tended to achieve lower results. The data analysis highlighted the need to implement specific intervention programs and new school policies to combat bullying.

3. Results

Our study aimed to understand the prevalence and effects of bullying among middle school students. We investigated four hypotheses about bullying in middle schools in Craiova, Romania, using a quantitative data collection method and a sample of 673 students. The data collection involved filling out the questionnaire face-to-face.

Demographic Data

A total of 50,4% of the respondents to the questionnaire were 14 years old, followed by 13-year-olds (32.6%) and 15-year-olds, who constituted 16.6% of the sample. The lowest response weights were obtained from pupils aged 15 years and over and 11-year-olds, who represented only 0.3% and 0.1%, respectively. Most of the students who participated in our research (99.3%) were students of the 7th (46.1%) and 8th (53.2%) grades, and the students who participated the least were in the 6th (0.3) and 5th (0.4) grades.

Our sample was relatively gender-balanced (50% boys; 49.8% girls), which was an advantage for our research because, in this way, we were able to make comparisons between the girls’ and boys’ experiences of bullying or to observe, for example, whether in some forms of bullying, girls are more predisposed to bullying than boys.

We opted to administer questionnaires to all four classes at the middle school level because bullying occurs at each of these levels and because, in this way, we were able to correlate the answers to certain questions according to the class in which the students were learning. Besides the students of the 6th (0.3%) and 5th (0.4%) grades, most of the students who participated in our research (99.3%) were students of 7th (46.1%) and 8th (53.2%) grades.

In the present study, we aimed to understand whether or not gender was a significant predictor of bullying victimization. Moreover, we were curious to find out if students with lower academic scores were more likely to be victims of aggression. In addition, we aimed to analyze if social support can be a protective factor in bullying prevention. Consequently, we examined the relationships between gender, academic performance, well-being, and bullying.

Question 21 from our questionnaire addressed students’ involvement in bullying incidents. In

Table 1, we report a Pearson correlation of 0.041, which leads us to the conclusion that there is a weak relationship between gender and involvement in bullying incidents, meaning that gender is not a significant factor in determining a person’s likelihood of being involved in a bullying incident.

While this applies to our sample, it does not mean that in other social or cultural contexts, the results will coincide. We observed during our examination of the existing literature that, when it comes to bullying, results can be inconsistent because of the nuanced nature of this phenomenon.

The data in

Table 2 and

Table 3 highlight that bullying is a prevalent problem in Romanian schools (when compared with the HBSC average). At age 13, both bullying and the victimization peak, 16% of boys and 14% of girls reported that they have been victims of bullying. We can also see that 16% of boys and 13% of girls of the same age admit to having bullied their peers. Gender differences are evident, with boys reporting slightly higher rates of involvement in bullying behaviors than girls, which can be explained by the different social and behavioral norms that are imposed on boys and girls, where boys may be more encouraged to display aggressive behaviors.

This observation offers valuable detail to the context of bullying in our sample, but it is not enough to confirm Hypothesis 1.

In

Table 4 we examined the relationship between students’ involvement in bullying and their relationship with their parents. In calculating the correlation between the two variables—a student’s relationship with parents and involvement in bullying incidents—a negative correlation of −0.148 (and a sig.

p-value = 0.000) was found, which led us to conclude that there is a moderate negative correlation between these two variables. The statistical calculation that we performed revealed that, where there is a better relationship with parents, children’s involvement in bullying incidents decreases. This confirms our third hypothesis.

Question 13 of our questionnaire aimed to obtain information on students’ social integration levels, starting from the indication of who they considered friends. The answers to this question indicated that 75.4% of the pupils had friends of the same age as themselves. In our view, this can be an extremely important supporting factor in the case of bullying, because, when friends are of the same age, the coping strategies of the victims (one of them would be sharing their experiences with friends) are more effective.

Question 12 aimed to understand the correlation between bullying and academic performance (−0.068). Although not significantly statistically significant (

p = 0.079), this finding exhibited a weak negative correlation (

Table 5). This means that students who have been involved in a bullying incident tend to have slightly lower academic performance than those who have not been victims or aggressors.

Items 31.1–31.17 from our questionnaire aimed to analyze the relationship between observational bullying and academic performance (

Appendix A). These questions addressed students who were witnesses to bullying incidents. Contrary to our initial hypotheses (see H2), we found a significant correlation between witnesses to bullying incidents and academic performance: Q31.1 (

p = 0.002); Q31.2 (

p = 0.004); and Q31.12 (

p = 0.003). These findings indicate a consistent negative correlation, meaning that students who witnessed bullying victims or aggressors tend to have lower academic scores.

This is an interesting and unexpected result that partially confirms our fourth hypothesis. It also demonstrates that bullying can have a significant impact on the entire school environment, not only on those who are directly involved in the phenomenon. Thus, promoting a healthy and positive learning environment must be a prime objective in the Romanian educational system.

The statistical calculation for the Pearson correlation in

Table 6 showed a value of −0.186 between involvement in bullying incidents and perceptions of school safety: when students’ involvement in bullying incidents increases, their perceptions of general safety in the school that they attend decrease. Furthermore, we can observe a sig. (two-tailed) of 0.000 in

Table 4, which means that this correlation is strong and statistically significant.

Even though the studies that we consulted in the background research for this article have shown that there is a relationship between bullying and school performance, 59.7% of the students who responded to our questionnaire indicated that the bullying incident in which they were involved did not significantly affect their relationship with school and learning (

Table 7). For 9.6% of the pupils, the bullying incident made them not want to go to school as much. For this reason, we consider that some of the strategies for identifying cases of bullying should be based on an analysis of absenteeism and dropout. Hypothesis 2 is rejected.

This percentage of 9.6% also correlates with the 10.7% of the respondents who indicated that, after the bullying incident that they were involved in, they started to see school as an unsafe environment, while the other respondents stated that this did not significantly impact their concentration and performance at school or made them less willing to go to school and feel less safe in the school environment (

Figure 1).

Further, 156 (6.1%) respondents indicated that, following the bullying incident, they had difficulty concentrating at school and had poor school performance.

Consequently, we found that gender did not have a significant impact on bullying, students with strong social support were less likely to engage in bullying incidents, and observational bullying is a predictor of lower academic scores. However, for the role of aggressors and victims, bullying did not significantly impact their academic performance.

4. Discussion

Our study aimed to evaluate the prevalence and effects of bullying among middle school students from Craiova Municipality, Romania, and produced key takeaways that teachers and policymakers can apply in designing effective prevention programs.

We found that, contrary to our initial hypotheses, the correlation between gender and bullying victimization was weak. This highlights that, in the Craiovean area, gender is not a significant factor in understanding bullying.

The results challenge our initial expectations regarding academic performance and bullying. In opposition to prior studies consulted, our collected data showed that academic performance did not significantly predict bullying victimization or aggression.

The unexpected finding was that observational bullying predicted lower academic scores. This could potentially point to the far-reaching effects of bullying on the wider learning environment. Its impact can extend beyond the individuals directly involved, and it can also influence witnesses.

Boys reported higher victimization rates than girls, as presented in

Table 2 and

Table 3. Thus, Hypothesis 1 is confirmed. Nonetheless, our study results report a weak connection between bullying victimization and gender. Contrary to the studies we have consulted in the literature review, gender did not significantly influence bullying prevalence in our sample. This does not intend to contradict our previous finding but rather provides additional context and detail to understanding the complex phenomenon of bullying. These gender differences could be influenced by various behavioral and social norms that are pushed on boys and girls. Analyzing the connections between gender and bullying more in depth could be an interesting topic for future research.

When it comes to Hypothesis 2, we found a weak negative link between bullying and academic performance, both for victims and aggressors. The unexpected finding, however, was a significant correlation between bullying witnesses and academic performance.

For example, the results for Question 31.15 suggested a significant link between the two variables. Moreover, linking academic performance to questions 31.1, 31.2, 31.5, 31.7, and 31.12 indicated that students who witnessed bullying were likelier to have lower academic scores (

Appendix A).

Lacey and Cornell (

2013) argued that witnesses are just as affected by bullying as aggressors and victims. Their study analyzed 286 high schools in Virginia, USA. They found that a negative learning environment causes lower academic scores, which can explain our research results. Witnessing such incidents can cause distress, anxiety, a feeling of being unsafe, and lower academic scores. Other researchers also argue that this negative impact is not limited to victims; those who witness bullying also experience detrimental effects on their academic performance (

Rusteholz et al., 2021;

Zequinão et al., 2017).

When analyzing Hypothesis 3, we found that 75.4% of students reported having friends of the same age. This indicates that strong social support can be effective when combating bullying. This was also confirmed by

Ringdal et al. (

2020). Their study used a large survey comprising Norwegian adolescents. In addition, they argued that, without the protection of social support, adolescents are more likely to develop symptoms of stress and anxiety.

Collected data also showed that social support from parents and friends can act as a safety barrier for combating and preventing bullying. Students with stronger social support were less likely to engage in bullying behaviors. In addition, developing prevention programs would be more effective when relevant stakeholders, such as parents, guardians, teachers, and friends, are included. Therefore, H3 is confirmed.

Al-Smadi et al. (

2024) also claimed that social support partially eased students’ depressive symptoms.

Shaheen et al. (

2019) carried out a study in Jordan. They had a sample of 436 students and analyzed bullying victimization and the role of social support in this phenomenon. The authors reported that social support acts as a protective variable regarding bullying. In addition, they claimed that gender, age, social media, and support from family can all forecast bullying victimization. Moreover, adolescents who perceive higher levels of support from loved ones are less likely to experience bullying (

Cuesta et al., 2021;

Lee et al., 2022;

Shaheen et al., 2019).

Our study, however, showed that only 10.7% of students reported that bullying made them feel unsafe in the school environment, and 9.6% declared that they did not want to go to school anymore because of bullying. In contrast, 59.7% claimed that bullying did not affect their relationship with the school and learning environments. Only 6.1% reported difficulties focusing and performing well after a bullying incident. These data partially validate our fourth hypothesis (H4).

Kim and Chun (

2020) claimed that a positive school environment on an individual level reduces bullying and suicidal tendencies. In contrast,

Fleming and Jacobsen (

2010) argues that victims of bullying report higher levels of sadness, hopelessness, loneliness, insomnia, and suicidal ideation.

We found a moderate negative correlation between a student’s relationship with their family and bullying. A better relationship with parents was associated with less involvement in bullying actions. In addition, we report a strong negative correlation between bullying and students’ perception of school safety. This means that, if students consider the school environment to be unsafe, they are more likely to become involved with bullying. The existing literature supports this argument by stating that students who feel unsafe at school are more likely to be victims, bullies, or both. This is linked to feelings of sadness and a lack of belonging (

Glew et al., 2008;

Goldweber et al., 2013).

Our study highlights the multidimensionality and complexity of the bullying phenomenon and underscores the importance of social factors such as family, friends, and social support. At the same time, a good perception of the school environment is imperative in preventing bullying. Gender did not seem to be a significant factor in our sample; however, a deeper analysis of its implications is still necessary in other contexts.

Ciucă (

2019) claimed that bullying is a major issue in the Romanian educational system. In addition, he encouraged further research on this topic due to the existing literature focusing on violence for the most part. After comprehensively reviewing the literature, we found that specificity is the only common factor in understanding the phenomenon of bullying. What predicts bullying in one region, country, or even city may differ from other areas. Furthermore, we should expand our scope and look at other variables, such as school dropout rates or absenteeism, and adopt an analytical approach to designing prevention programs for them to be effective. This includes conducting research before implementing any new strategies in schools. More targeted interventions are needed that take into account the specific social dynamics and risk factors present in middle schools (

Monopoli et al., 2022;

Ybarra et al., 2019).

4.1. Recommendations for Policymakers and Teachers

Educational institutions should design school-wide anti-bullying policies that define bullying clearly, outline procedures rigorously, and determine consistent disciplinary measures in case of incidents.

Anti-bullying initiatives should be tailored to address bullying from different points of view, such as conflict management skills, social and emotional learning, and advocating for a positive school environment.

We highlight that creating prevention programs does not mean a one-size-fits-all approach. Our results show that programs should be adjusted to specific cultural and contextual factors.

Educational institutions should provide extensive training for teachers to combat bullying. Teachers need to learn about strategies that cultivate positive student–teacher relationships.

In addition, our study demonstrates that peers and the home environment could have a significant effect on bullying prevalence. We suggest collaborating with parents/guardians and friends to raise awareness of bullying, its effects, and methods to support victims, aggressors, and witnesses as well.

Our research provides evidence supporting that witnesses are just as much affected by this harmful phenomenon as aggressors or victims. This indicated that prevention programs should include all of the stakeholders regarding bullying.

Campaigns and community-based events could also raise awareness of the harmful influence of bullying on the school environment.

4.2. Study Limitations

It is important to highlight that our study was based on a sample from the Craiovean Municipality and region, limiting its potential to generalize the results at the national level.

In addition, a self-reporting approach to behavior can cause biases, because students can be shy or might not want to admit that they have been involved in bullying incidents, no matter if they were victims, witnesses, or aggressors.

Another important aspect to mention is that contextual factors such as the school’s characteristics or the family background of students have not been evaluated comprehensively. Future studies could include a qualitative or longitudinal approach and a more diverse sample both from urban and rural areas. This way, we could improve our understanding of the phenomenon of bullying in Craiova, Romania.

5. Conclusions

Our research generated several key findings that challenged our initial expectations and offered new insights into the nuanced relationships between bullying, academic performance, social support, and gender.

Results underscore that academic performance did not predict bullying victimization or aggression significantly. Instead, we argue that students who witness aggression (observational bullying) were more likely to have lower academic scores, suggesting the possible extensive effects of bullying on the wider academic environment, even for those students who were not directly involved.

Decisively, our data showed that support from friends and family can be a protective factor against bullying prevalence. This provides evidence for the potential of bullying prevention programs, including key parties from students’ social support networks.

When it comes to the connection between gender and bullying, our statistical analysis reported a weak connection, although we noted that boys reported higher victimization rates than girls. This observation brings nuance and context to the dynamics of bullying among Craiovean middle school students.

Some of our initial hypotheses were rejected. Our literature review suggested that gender and academic performance significantly correlate to bullying. Although boys reported higher rates of bullying, we identified only a weak link (r = 0.041) between bullying and gender. In the same way, we identified a weak correlation between bullying and academic performance for aggressors and victims (

p = 0.079;

Table 2). However, we found that observational bullying is linked significantly with academic performance.

Social support from the family had a moderate negative correlation (−0.148). This underscores the importance of having a positive and healthy home environment. Furthermore, students’ perception of the school environment is crucial when creating a positive learning environment, which can also predict involvement in bullying.

We acknowledge that the existing literature and our study findings underscore that bullying remains a major issue within the Romanian educational system. However, it is important to highlight that the current research was conducted as a case study focused on Craiova. While the results provide insights into understanding bullying in this particular context, we cannot generalize these findings at the national level without further investigation.

Based on our findings, the potential of developing bullying prevention programs is undeniable. Policymakers, teachers, and institutional leaders should focus on some key points when developing bullying prevention initiatives to elevate students’ well-being and the overall learning environment. The goal is to advocate for a positive school climate where students can cultivate both academic and personal growth while feeling safe and comfortable.

Bullying prevention programs should target all students, not only victims or aggressors. Moreover, they should include key players from students’ social networks, such as parents and friends. Teachers and educators would benefit from participating in training sessions that equip them with the knowledge and skillset to prevent and combat bullying. In addition, there should be a clear and rigorous definition of bullying aggression incidents, and they should be treated accordingly.

After comprehensively studying this phenomenon, we must highlight that bullying is culturally and contextually specific. Further research should focus on broadening our investigation to other important factors and predictors, such as mental health, dropout rates, or absenteeism. Analyzing correlations between these variables could bring us closer to the cause of the problem. In addition, we argue that there needs to be more methodological diversity. The existing literature would benefit from longitudinal or qualitative research to further deepen our understanding of bullying.

Only from a complex and contextualized approach can we design prevention programs that will truly serve Romanian students better. Bullying is a nuanced and sophisticated phenomenon. It can take on many forms and influence numerous lives. Only by continuing to carry out research in this area can we make a difference in combating bullying in the Romanian educational system.