Abstract

This systematic review explores key characteristics of effective vocational education and training (VET) teachers’ professional development and the transfer of its results into educational practice. Through thematic analysis of 24 journal articles indexed in Scopus and/or Web of Science from 2014 to 2024, the review identifies ten features of effective professional development and eight attributes supporting its transfer to practice. Effective professional development and its transfer emphasise reflection, engagement in professional communities of practice, and targeted approaches that address VET teachers’ needs. While effective professional development focuses on providing relevant, active, and collaborative learning experiences, effective transfer to practice places additional emphasis on teachers’ capacity, transformative leadership, personally significant, authentic, transformative, and supportive learning experiences that ensure new knowledge and skills are effectively applied in daily professional activities. This review offers recommendations to enhance the systematic organisation of professional development, promoting more targeted approaches to improve teaching quality in VET.

1. Introduction

The education system is constantly changing in response to changes in all areas of life. Sometimes changes in education take the form of educational reforms, which have a direct impact on educational institutions, teachers, and changes in the organisation of the learning process. Educational reforms require teachers to continuously improve their practice and review their approaches to teaching. Major changes take place gradually and their impact can only be assessed in the long term. Therefore, the involvement of teachers in the process of professional development is crucial, as teachers continue to improve their knowledge and skills beyond their initial education (Boeskens et al., 2020).

Following the definitions proposed by Ciraso (2012), del Arco et al. (2023), Gil et al. (2022), Isna (2021), and Schoeb et al. (2021), transfer to practice captures both the behavioural changes that occur after training and the long-term maintenance of professional knowledge and skills. It serves as a core indicator of the effectiveness of professional development, reflecting how successfully teachers embed the outcomes of professional learning into meaningful and enduring improvements in their practice. In this study, “transfer to practice” refers to the degree to which teachers apply the knowledge, skills, and abilities acquired during professional development programmes in their everyday educational contexts. It encompasses not only the initial application of new knowledge and skills but also the sustained use and integration of these over time to enhance teaching practices and improve educational outcomes.

In vocational education and training (VET), the need for effective professional development is particularly acute. According to the European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training (Cedefop) report (2022), VET teachers and trainers play a crucial role in preparing students for the workforce by providing up-to-date knowledge and skills suited to an evolving socioeconomic environment. The report emphasises also the need to remove barriers to continuous professional development for VET teachers and trainers in both school-based and work-based settings (European Centre for Development of Vocational Training, 2022).

The scientific literature underscores the dual role of VET educators, who must remain informed about innovations in their field while also possessing strong pedagogical skills to modernise the learning experience (Andersson et al., 2018; Köpsén & Andersson, 2017). To cultivate a competitive generation, VET teachers must continually improve their expertise to meet market demands.

Koay’s (2023) study on professional development in general education indicates that negative experiences related to professional development activities can discourage teachers from ongoing learning, highlighting the importance of understanding teachers’ needs and providing varied opportunities to organise and manage professional development effectively. Sandal (2023) points out a similar idea—that effective teachers’ professional development should link to the local context and development of a culture of assessment in schools.

Professional development among VET teachers has been conceptualised through several theoretical frameworks, each offering different perspectives on how adults learn and change. A critical understanding of these frameworks is important for identifying which approaches are most relevant for VET teachers’ growth.

Both individual and organisational factors influence the implementation of pedagogical changes. At the individual level, teachers’ motivation (Canrinus et al., 2011; Kirkpatrick & Kirkpatrick, 2006), doubts and beliefs (Hall & Hord, 2011), and self-efficacy (Bandura, 1997; Day, 2002) are critical to effective change. Such factors align with the notion that the most effective change occurs as a result of the following actions: cooperation with other colleagues in creative communities of practice; collaborating, co-creating, merging personal views as well as ideas into a joint vision; and finally, dialogue, reflection, and discussions stemming from different perspectives (Sandal, 2023; Toepper et al., 2021; Zhou et al., 2022, 2024). Teachers’ belief in their ability to successfully implement new practices plays a crucial role in the effectiveness of professional development programmes.

Transformative learning theory (Mezirow, 1989, 1991) is a foundational model for understanding professional development, emphasising how critical reflection leads to profound changes in teachers’ perspectives and practices. Transformative learning is highly relevant for VET, where professional identity formation often requires deep shifts in thinking to integrate academic knowledge with industry practices. Transformative learning has been explored extensively both in VET (Sappa et al., 2016) and general education (Boylan & Woolsey, 2015), emphasising active, problem-based learning within diverse social contexts (Jarvis, 1987). Problem-based learning focuses on solving real-world problems, encouraging critical thinking, collaboration, and practical application of knowledge, making it highly relevant also for VET teachers. In prior studies (de Paor, 2018; Sandal, 2023; Zeggelaar et al., 2018), frameworks for VET teachers’ professional development largely build on Guskey’s and Kirkpatrick’s models (Guskey, 2000; Kirkpatrick, 1998; Kirkpatrick & Kirkpatrick, 2006), evaluating effectiveness through teacher satisfaction, practice change, and student outcomes.

Situated learning theory (Lave & Wenger, 1991) emphasises learning in context and through participation in communities of practice (Wenger, 1998), aligning well with the need for real-world vocational settings and highlighting the social dimension of professional growth. Learning, in this view, occurs through active engagement in professional communities where shared values, language, and practices are developed. In the VET context, situated learning explains how teachers’ engagement with industry partners and peer networks contributes to maintaining professional relevance.

Furthermore, theories from the field of organisational learning, such as Peter Senge’s concept of the learning organisation, offer additional insights into understanding VET teacher professional development. His theory emphasises the importance of ongoing professional development, innovation, continuous learning, and adaptation within organisations (Senge, 1994).

Complementing these perspectives, Ley et al. (2020) proposed the concept of knowledge appropriation, which connects scaffolded learning with knowledge maturation in workplace environments. Knowledge appropriation views professional development as a dynamic, situated process where new knowledge is actively integrated, adapted, and internalised through reflective engagement in authentic work settings. This model enriches the understanding of how VET teachers embed newly acquired skills and knowledge into their daily practices, reinforcing the role of social learning and workplace collaboration in sustaining professional growth.

In the context of evolving professional roles and pedagogical expectations, it is also essential to understand how teachers internalise and apply new knowledge in complex workplace settings. These theories collectively inform a more holistic view of professional development in VET.

Technological innovation models, such as the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) (Davis, 1989) and the Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology (UTAUT) (Maomani, 2020; Venkatesh et al., 2016) explain how perceived usefulness and ease of use affect individuals’ willingness to adopt new technologies. In VET, where digitalisation of workplaces is increasingly prevalent, TAM and UTAUT help illuminate factors influencing teachers’ technology integration into pedagogical practice. Different theoretical perspectives, such as motivational, cognitive, affective, and behavioural notions of individuals form the basis of these two models. They substantiate factors that influence users’ decisions to embrace or reject a particular technology and identify the key determinants of user acceptance. In addition, they provide insights into how technology can be designed or modified to enhance its appeal and usability, thereby encouraging broader adoption. However, these models primarily address specific domains (e.g., technology adoption) and are less comprehensive than broader learning theories in explaining professional development as a whole.

The concepts of change and adoption are also actualised in the Concerns Based Adoption Model (CBAM), which includes three components—Stages of Concern, Levels of Use, and Innovation Configurations. These three components focus on educators’ cognitive concerns and work together to describe the emotional and behavioural responses of individuals during the implementation of educational innovations (Anderson, 1997; Hall, 1974; Hall & Hord, 1987). The CBAM is well-known in the evaluation of the implementation of changes in education.

The Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK) framework developed by Mishra and Koehler (2006) outlines the teachers’ need for effective technology integration, emphasising the interplay between content, pedagogy, and technology. It has significantly influenced teacher education and professional development by providing a theoretical basis and describing the kinds of knowledge needed by a teacher for effective technology-enhanced teaching (Koehler et al., 2013, 2014; Mishra & Koehler, 2006). While TPACK is valuable for teacher training related to technology, it does not fully capture the broader processes of professional growth across all aspects of VET teachers’ roles.

In critically reflecting on above mentioned theoretical frameworks, transformative learning, situated learning, and organisational learning theories appear particularly significant for understanding professional development among VET teachers. They emphasise not only the acquisition of new skills but also the transformation of professional identities and the importance of community engagement. In contrast, models like TAM, UTAUT, CBAM, and TPACK serve important, but more supportive and specialised roles, particularly when considering the integration of digital technologies or other educational innovations.

Thus, the professional development of VET teachers should be seen as a complex, multi-dimensional process, where transformative shifts in thinking, situated learning through professional communities, and strong self-efficacy beliefs are central. Technological models contribute valuable insights into specific challenges, but broader learning theories remain more central to the design and evaluation of effective VET teacher professional development.

While the professional development of general education teachers has been discussed in the scientific literature, there is a lack of systematic analyses of effective teachers’ professional development and its practical application in VET. Our study addresses this gap by conducting a systematic literature review of effective VET teacher professional development and its transfer to practice for the purposes of exploring the following research questions:

- RQ1: What characterises and promotes effective professional development of VET teachers?

- RQ2: What characterises and promotes the effective transfer of VET teachers’ professional development into practice?

2. Materials and Methods

Following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) framework (Page et al., 2021), a systematic review was performed by analysing the Scopus and Web of Science databases, searching articles in English published in journals from January 2014 to March 2024. Scopus and Web of Science were chosen as they are prominent academic databases with a very large collection of international journals and high-quality peer-reviewed publications. Thematic analysis was used to identify and interpret the characteristics of effective professional development of VET teachers and its transfer to their professional practice.

2.1. Selection Process

The selection of articles was carried out by two authors, considering the following aspects:

- (1)

- Seven selection criteria (both inclusion and exclusion criteria): language, type and year of publication, type of research, target group, full-text option and answers to research questions (see Table 1);

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for article selection.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for article selection. - (2)

- Three-step searching queries with the Boolean operators “AND” and “OR” conducted in Scopus and Web of Science databases:

- Article, abstracts, keywords = vet AND teachers AND professional AND development;

- Article, abstracts, keywords = vet AND teachers AND professional AND development AND transfer;

- Article, abstracts, keywords = vet AND teachers AND professional AND development AND effective OR effectiveness OR effect OR impact OR influence.

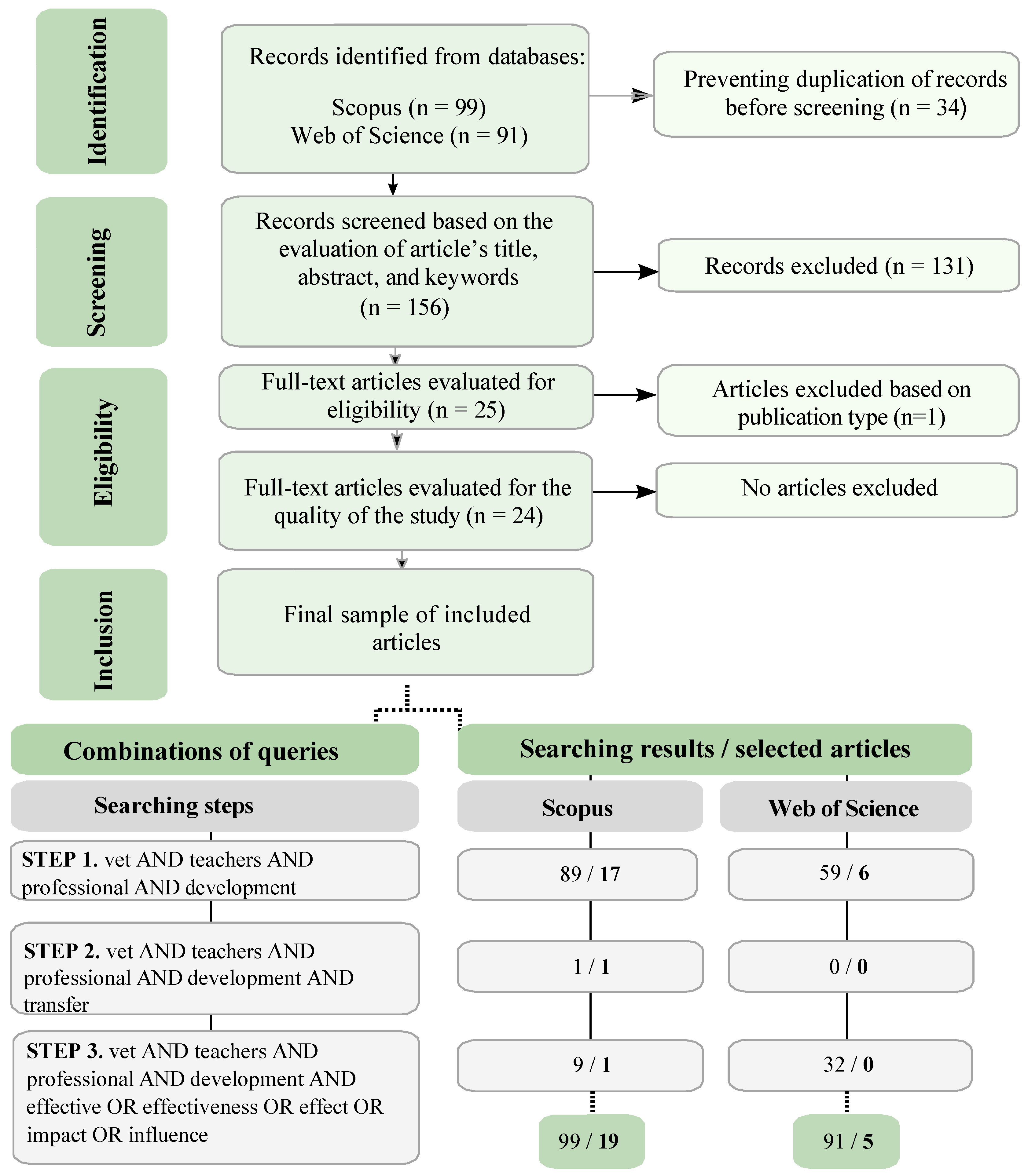

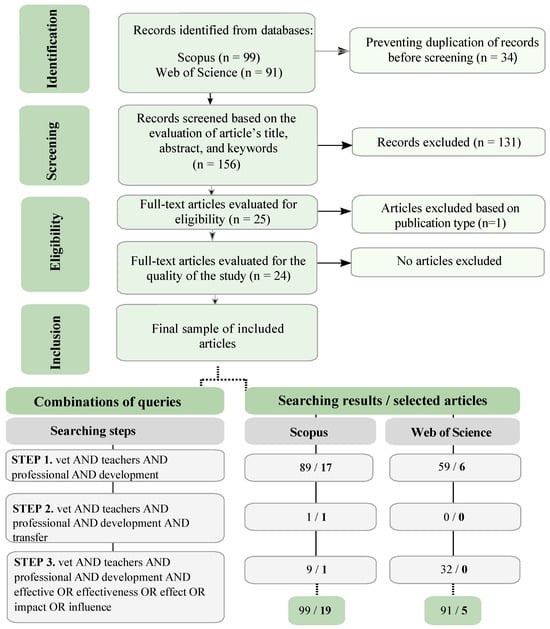

Combinations of the selected queries were searched in the titles, abstracts, and keywords of the articles available in the databases. A total of 190 articles were identified, with 34 duplicates removed. The first-step query yielded the highest number of articles (n = 148). During the screening process, titles, abstracts, and keywords of 156 articles were carefully evaluated, resulting in the exclusion of 131 articles as irrelevant. A full-text review was conducted on 25 articles, with one article excluded at this stage due to not meeting the publication-type criterion. Ultimately, 19 articles from Scopus and 5 from the Web of Science met the inclusion criteria. Thus, a total of 24 articles were selected for further analysis. The article selection process is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The selection of articles according to the PRISMA guidelines.

2.2. Quality Assessment

Nineteen criteria were used to assess the quality of the selected 24 articles. The quality was independently assessed by two authors based on guidelines for extracting data and quality assessing primary studies in educational research developed by the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information Centre (EPPI Centre, 2003) and Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Qualitative Studies Checklist (CASP, 2024). The assessment was made using the scale from 0 to 2 and each article was evaluated according to nineteen quality criteria with “relevant” (2 points), “partly relevant” (1 point), or “not relevant” (0 points), creating a potential score range of 0 to 38 points and assigning four quality levels: high (30–38 points), good (20–29 points), average (10–19 points), or low (0–9 points). The option “not applicable (N/A)” was also included.

To assess the reliability of the independent assessments by the two researchers, an inter-rater reliability (IRR) measure was performed with Cohen’s Kappa coefficient, using IBM SPSS software (version 22). Overall quality control of the selected articles by a third researcher was also provided. According to the results of IRR, there was mostly very good or excellent inter-rater agreement between the evaluators, as the IRR ranged from 0.759 to 1.000, and only in one case was the inter-rater agreement slightly lower, i.e., IRR = 0.620 (see Appendix A). In one case, Cohen’s Kappa was not calculated because one evaluator’s scorings were constant.

2.3. General Characteristics of the Selected Articles

A brief overview of selected publications is provided in Appendix B. Studies identified across both databases represent a broad geographical range. Australia (n = 8) and Sweden (n = 5) are the most represented countries, followed by the Netherlands (n = 3), Norway (n = 2), and China (n = 2). Finland, Denmark, Ireland, Canada, Germany, Switzerland, Italy, Poland, Mexico, and Kenya are also represented in the sample. Most selected articles (n = 23, 95.8%) are based on empirical research, employing various data collection methods: surveys and tests (8 articles), structured or semi-structured interviews (10 articles), focus group discussions (3 articles), and mixed methods (2 articles). While 13 studies primarily used qualitative data analysis, 10 articles applied quantitative data analysis, occasionally combined with qualitative methods. The highest number of relevant publications between 2014 and 2024 appeared in 2018 (n = 6) and 2023 (n = 5).

2.4. Thematic Analysis

To analyse the selected articles, the researchers employed a qualitative thematic research methodology, following the approach outlined by Braun and Clarke (2006). Thematic analysis is a qualitative method used to uncover deeper insights from data, facilitating the exploration and interpretation of themes emerging from the selected articles. The thematic analysis was conducted through the following six steps:

- The first step—familiarisation. The researchers read through the article texts, examined titles, keywords, main theoretical concepts, findings, and other essential aspects, and extracted necessary information in a structured manner, using a MS Excel spreadsheet.

- The second step—coding. Key points and recurring ideas were highlighted in bold, enabling the researchers to identify common ideas (codes) derived from the articles.

- The third step—generating themes. The researchers grouped codes into common themes.

- The fourth step—reviewing themes. The articles were reviewed twice, with emphasis placed on two research questions. As a result, the themes were reviewed and refined to ensure data accuracy, clarity, and coherence, enabling the researchers to align the themes closely with the research questions within the VET context.

- The fifth step—defining and naming themes. This step led to the final definition of themes related to the key characteristics of effective VET teachers’ professional development and the transfer of its outcomes into educational practice (see Appendix C, Appendix D and Appendix E).

- The sixth step—producing the report. The researchers wrote up the analysis, addressing each theme in turn (for more detail, see Section 3 “Results”).

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of Effective Professional Development of VET Teachers

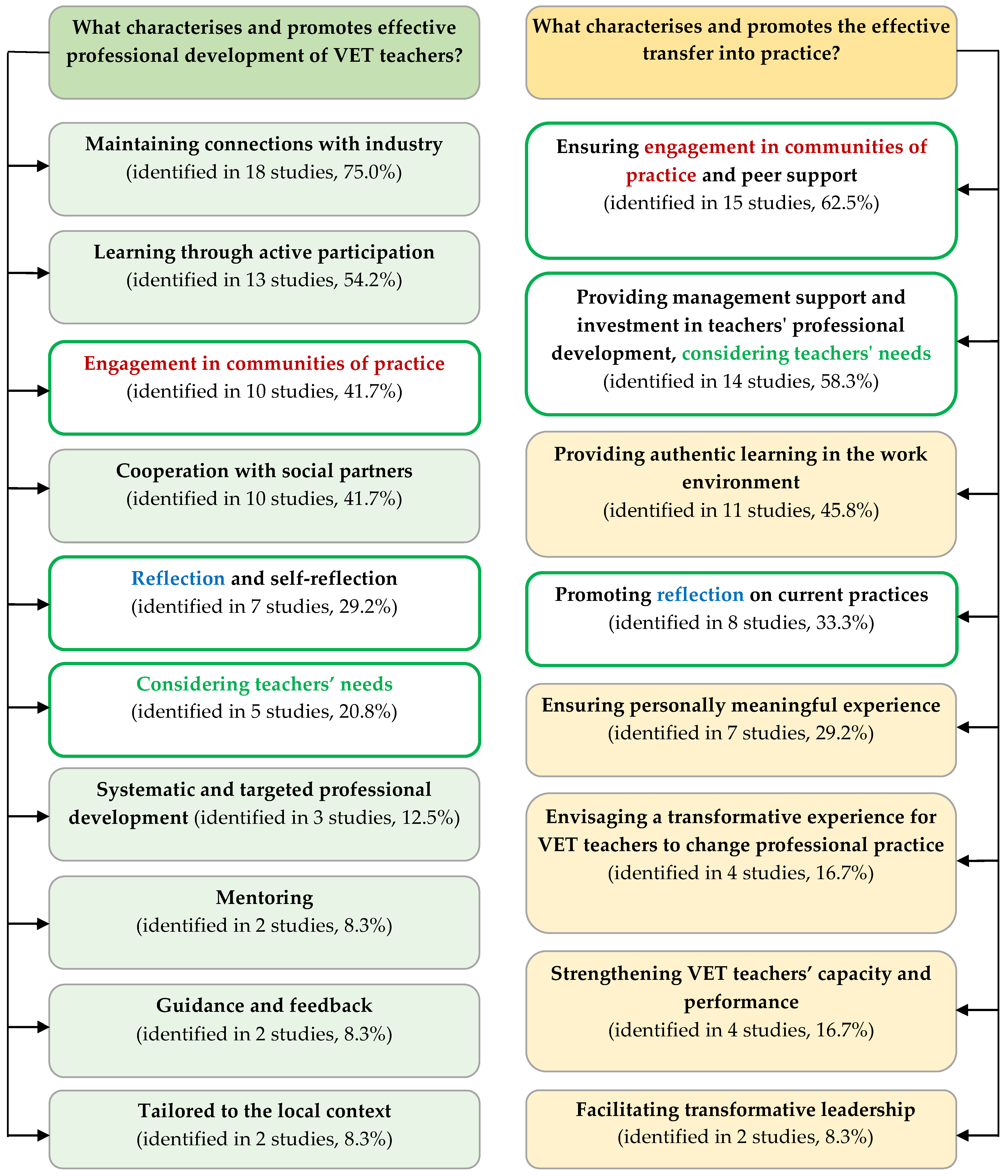

The authors of the selected articles identified several conditions necessary for effective professional development of VET teachers. Data from the selected 24 articles were synthesised using thematic analysis, resulting in the identification of 10 key characteristics of VET teachers’ effective professional development. Among these, the most referenced were maintaining connections with industry (identified in 18 articles, 75.0%), learning through active participation (identified in 13 articles, 54.2%), engagement in creative communities of practice (identified in 10 articles, 41.7%), and cooperation with social partners (identified in 10 articles, 41.7%) (see Appendix C). The themes in this section are presented in descending order based on the number of studies referencing each theme. For clarity, the main themes are bolded in the text.

As noted, maintaining connections with industry is one of the most discussed characteristics of effective professional development (identified in 18 articles). Andersson et al. (2018) emphasised that VET teachers should retain ties with the professional networks they represent. The role of a VET teacher is characterised by a ‘dual identity’, balancing roles as both practitioner and educator. Effective professional development is shaped by this duality, bridging VET institutions, workplace environments, and social life, and recognising other boundary practices where teachers actively engage in the professional development process. A key aspect of VET teachers’ professional competence is maintaining knowledge and skills from their original profession. Effective professional development occurs when VET teachers engage with professional networks and regularly improve their skills, thereby aligning with industry standards. Zhang et al. (2022) also indicated that VET teachers should engage in production and operational processes within industry settings. Zeggelaar et al. (2022) further highlighted the value of industry-based learning activities. According to their findings, teachers’ professional identities are best cultivated through workplace interaction and professional development within companies. Professional training is largely ineffective if disconnected from industry environments; thus, it is crucial that VET institutions and employers ensure robust links between industry and education.

Learning through active participation is referenced in 13 studies (Andersson et al., 2018; Andersson & Köpsén, 2018, 2019; Antera, 2022; Ballangrud & Nilsen, 2021; Beverborg et al., 2015; Gagnon & Dubeau, 2023; Jin et al., 2021; Njenga, 2023; Sandal, 2023; Schmidt, 2019; Tran & Pasura, 2021; Tyler & Dymock, 2019). These studies note a shift in the role of VET teachers from passive recipients to active learners, emphasising active involvement through observation, discussions, planning, feedback, and reflection. Various training formats such as observing colleagues, shadowing, collaborating with professional organisations, participating in educational excursions, and attending courses and seminars are frequently mentioned opportunities for VET teachers’ professional development (Andersson & Köpsén, 2018).

Another essential feature is engagement in communities of practice (mentioned in 10 articles). VET institution managers play a significant role by motivating teachers to establish and maintain active communities of practice for effective professional development (Ballangrud & Nilsen, 2021). Andersson et al. (2018) underscored the value of situated knowledge within specific communities of practice and identity formation through the interaction of different professional communities. Professional learning communities are particularly vital for early-career VET teachers (Gagnon & Dubeau, 2023). A competent VET teacher understands the objectives of the professional community and can implement activities to achieve them. Organisational changes that bridge the gap between educational and industry environments are encouraged to support VET teachers as active members of both communities.

Cooperation with social partners is crucial for effective professional development, as highlighted in 10 studies (Antera, 2022; Gagnon & Dubeau, 2023; Jin et al., 2021; Köpsén & Andersson, 2017; Njenga, 2023; Sandal, 2023; Schmidt, 2019; Tyler & Dymock, 2019; Zeggelaar et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2022). Researchers recommended developing professional development programmes in cooperation with social partners, trade unions, and employers.

Reflection and self-reflection are mentioned as essential elements for effective professional development in seven studies (Antera, 2022; Beverborg et al., 2015; Gagnon & Dubeau, 2023; Hommel et al., 2023; Jin et al., 2021; Sappa et al., 2016; Tyler & Dymock, 2019). These practices are integral to addressing the individual needs of VET teachers and exploring various ways to fulfil them. Self-reflection, viewed as an individual learning activity, allows teachers to apply and transform industry experience, creating a basis for ongoing effectiveness in VET.

Considering VET teachers’ needs when designing professional development programmes is highlighted in five articles (Ballangrud & Nilsen, 2021; Beverborg et al., 2015; Sandal, 2023; Sappa et al., 2016; Serafini, 2018). Identifying and listening to teachers’ needs during programme planning is crucial to effective professional development. Negative experiences can lead to resistance towards further professional development. Thus, meaningful engagement with ideas, resources, and materials, along with autonomy in selecting programme content, helps ensure a successful professional development process (Dymock & Tyler, 2018).

Three studies emphasise the importance of systematic and targeted professional development (Dymock & Tyler, 2018; Smith & Tuck, 2023; Tran & Pasura, 2021). Evaluating the effectiveness of professional development requires a clear purpose, an understanding of conditions, and a context in which it is to be delivered (Zeggelaar et al., 2018).

Mentoring within the workplace is highlighted by Gagnon and Dubeau (2023) and Jin et al. (2021). Expert mentorship is seen as an effective tool, enhancing motivation and guiding novice teachers towards improved performance. Such an approach makes it possible to increase motivation and encourage novice teachers to improve their work through providing proper guidance and feedback (Jin et al., 2021). Specific, detailed feedback is beneficial, especially for early-career educators (Beverborg et al., 2015; Sandal, 2023).

Lastly, contextual factors must be considered, as noted in two articles (Serafini, 2018; Zeggelaar et al., 2018). Models or practices should be tailored to the local context, considering infrastructure, economic factors, and regulatory frameworks to ensure compatibility with the professional education system and industry priorities.

3.2. Characteristics That Support the Effective Transfer of VET Teachers’ Professional Development

The systematic analysis of publications in the Scopus and Web of Science databases enabled the identification of eight critical characteristics that support the effective transfer of VET teachers’ professional development. These characteristics are summarised in Appendix D. The themes in this section are presented in descending order based on the number of studies referencing each theme. For clarity, the main themes are bolded in the text.

Among the most crucial factors for the successful transfer of professional development outcomes were engagement in communities of practice and peer support, as highlighted in 15 studies (Andersson et al., 2018; Andersson & Köpsén, 2018, 2019; Antera, 2022; Ballangrud & Nilsen, 2021; Beverborg et al., 2015; de Paor, 2018; Gagnon & Dubeau, 2023; Njenga, 2023; Schmidt, 2019; Serafini, 2018; Tyler & Dymock, 2019; Zeggelaar et al., 2018, 2022; Zhang et al., 2022). A strong community of practice provides teachers with a support network that enhances their confidence and reinforces their professional knowledge, facilitating continuous engagement with learning. Through collaboration, teachers deepen their understanding of shared resources, language, symbols, values, and traditions, treating these as assets for the collective. Communities of practice also encourage collaboration and discussion among teachers, allowing them to exchange insights, address challenges, and refine their practices through joint problem solving. This collaborative approach activates cognitive engagement, promotes goal clarity, and aligns professional development with teachers’ satisfaction, enhancing the likelihood of transferring newly acquired knowledge to their teaching. A supportive organisational climate is also essential for successful knowledge transfer. Teachers benefit from peer support when implementing new knowledge, for instance, through lesson observations and feedback, which positively influences their competence and practice while also benefiting students’ achievements (Hommel et al., 2023).

Management support at the VET institution, coupled with targeted investment in teachers’ professional development that considers teachers’ needs, is another key factor in facilitating learning transfer, as noted in 14 studies. Sandal (2023) argues that cultural changes within schools and alignment of professional development with teachers’ needs are largely driven by management involvement. Professional development should be embedded in the local context and contribute to cultivating a positive learning culture within the institution.

Authentic learning in the work environment, as mentioned in 11 studies (Andersson et al., 2018; Andersson & Köpsén, 2019; Antera, 2022; Ballangrud & Nilsen, 2021; de Paor, 2018; Dymock & Tyler, 2018; Gagnon & Dubeau, 2023; Köpsén & Andersson, 2017; Njenga, 2023; Smith & Yasukawa, 2017; Tyler & Dymock, 2019), are essential for maintaining and improving on teachers’ professional identities and competencies. Effective transfer of professional development requires regular communication and collaboration among practitioners across different organisations. Communication between social stakeholders, such as government, private enterprises, trade unions, educational institutions, and educators, should be facilitated to support consistent knowledge exchange. Andersson and Köpsén (2019) stress the importance of authentic learning within workplace settings. The digital age necessitates that employers offer professional development whereby VET teachers engage in authentic tasks. In the future, digital solutions may play a critical role in supporting interregional communication, further enhancing the transfer of knowledge by enabling cross-industry collaboration and real-world application of skills in the workplace (Antera, 2022).

Reflection on current practices is another vital component in the transfer process, as emphasised in eight studies. The ability to critically assess and evaluate one’s own practice enables teachers to discern which aspects of new knowledge are most valuable for enhancing existing approaches. Hommel et al. (2023) outlined three perspectives for effective reflection: (1) an individual action-process perspective, considering motivation, knowledge, and emotions; (2) a critical perspective, which involves assessing areas for content improvement; and (3) a collaborative perspective, which supports shared vision-building and leadership that promotes change.

The transfer of professional development is much more successful if a personally meaningful experience has been provided. The individual assigns significant value and meaning to both professional development and the implementation of change after the acquisition of new knowledge, as mentioned in seven studies (Andersson et al., 2018; Antera, 2022; Ballangrud & Nilsen, 2021; Dymock & Tyler, 2018; Njenga, 2023; Serafini, 2018; Tran & Pasura, 2021). Accordingly, the offer of training programmes must be designed by taking into account the specific professional development needs of different subgroups even within the same occupational group, as they differ in terms of purpose, content, and required scope of training (Dymock & Tyler, 2018).

The effectiveness of transferring professional development into practice is largely dependent on whether the development programme prompts transformations in existing practices or introduces new perspectives, providing transformative experience to change practice. Transformational impacts on teachers’ practice, as a result of professional development, are discussed in four studies (Beverborg et al., 2015; Dymock & Tyler, 2018; Hommel et al., 2023; Jin et al., 2021). The more tailored the professional development is to the needs of different teacher groups within the VET sector, the more effectively it embeds into practice.

Strengthening teachers’ capacity and performance also plays a significant role in the transfer process, as indicated in four studies (Hommel et al., 2023; Njenga, 2023; Serafini, 2018; Zeggelaar et al., 2018). A teachers’ ability to dedicate time and energy towards the application of new knowledge is crucial. The availability of resources, such as time, tools, and institutional support, further determines how effectively teachers can integrate their professional learning into daily practice (Njenga, 2023).

Transformative leadership, as mentioned in two studies (Beverborg et al., 2015; Hommel et al., 2023), is an essential factor in supporting teacher learning through teamwork. Transformational leadership fosters teachers’ capacity and commitment to extend beyond current capabilities, prompting teachers to make extra efforts and apply constructive changes in pedagogical practice. Through active participation in professional learning activities, teachers not only drive their own professional growth but also contribute significantly to the improvement of educational practices and, ultimately, to students’ learning outcomes.

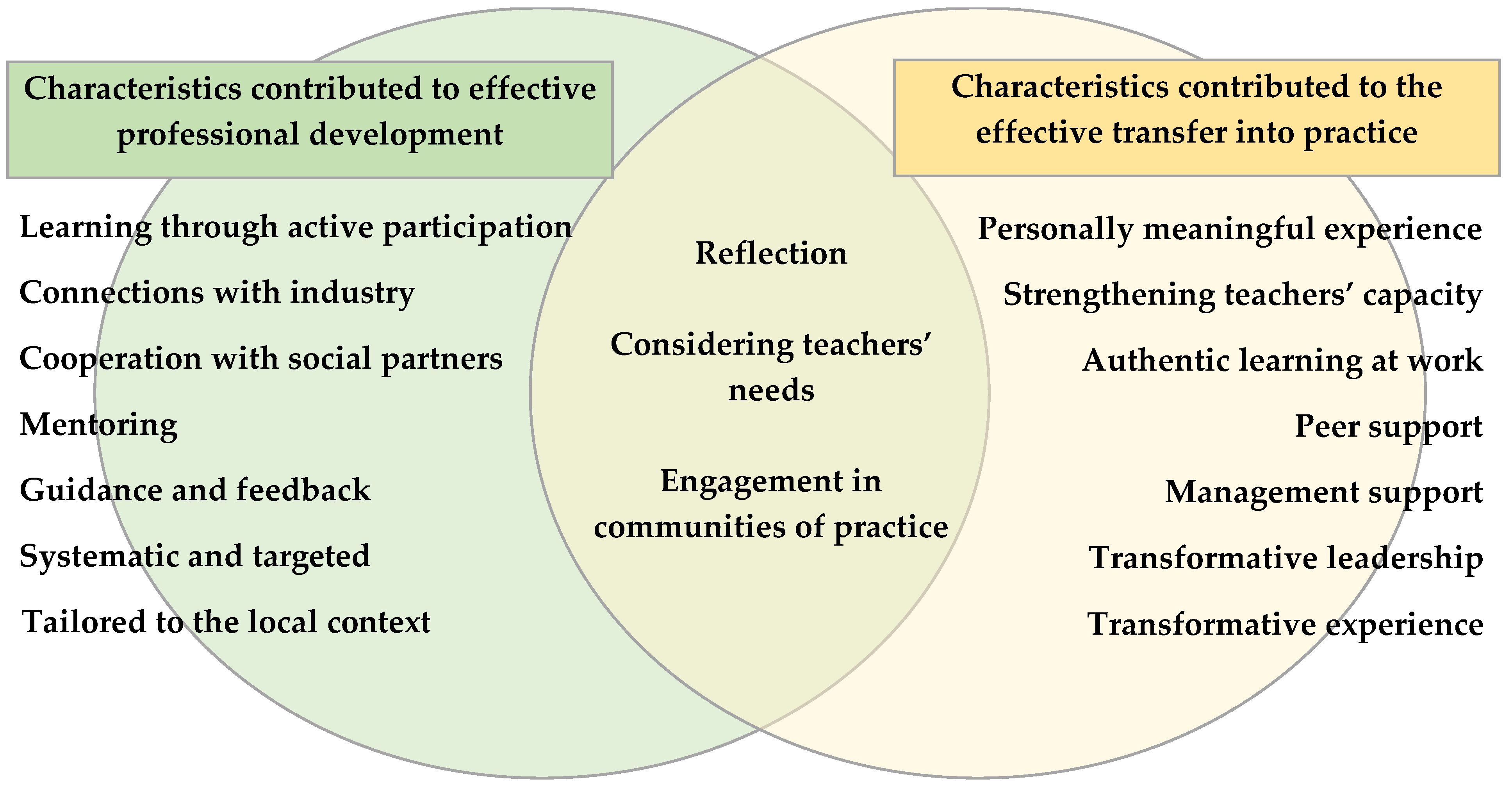

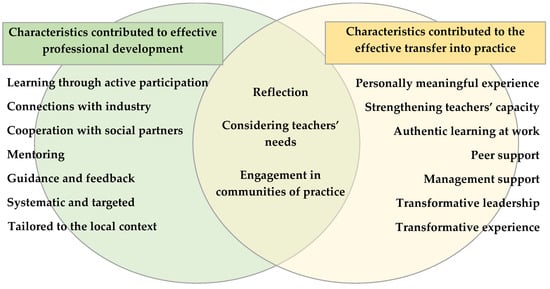

To summarise, the characteristics of effective professional development for VET teachers and those supporting its transfer into practice share several common elements but also have distinct emphases (see Figure 2 and Appendix E). Themes such as reflection, engagement in communities of practice, and consideration of teachers’ needs are prominent in both sections, highlighting their foundational role. Professional development is particularly characterised by themes such as maintaining connections with industry, learning through active participation, cooperation with social partners, and systematic and targeted approaches that offer relevant, collaborative, and practical learning opportunities. In contrast, the transfer of professional development into practice is strongly supported by authentic learning at work, strengthening teacher capacity, personally meaningful experiences, transformative leadership, and transformative experiences—all of which enable the sustained integration of new knowledge and skills into everyday teaching.

Figure 2.

The main results of thematic analysis.

Both effective professional development and effective transfer emphasise reflection, engagement in professional communities of practice, and targeted approaches that consider VET teachers’ needs. While effective professional development, potentially oriented on practical application of its results in practice, focuses on delivering relevant, active, and collaborative learning experiences, effective transfer to practice places emphasis on teachers’ capacity, transformative leadership, personally meaningful, authentic, transformative, and supportive learning experiences that ensure new knowledge and skills are embedded and sustained in day-to-day professional activities.

4. Discussion

This study provides a review of the attributes essential for effective VET teachers’ professional development and its transfer into practice. This review underscores that effective VET teacher professional development should integrate industry-relevant content with pedagogical skills, acknowledging the dual role of VET teachers as both educators and industry professionals. These findings align with an earlier systematic review by Zhou et al. (2022), who highlighted the importance of industry connections and real-world applications for VET teachers. This connection to industry reinforces teachers’ professional identity and practical skills, particularly through industry-based learning, with reflective practices serving as a core component of effective professional development.

Another significant finding is the importance of communities of practice and collaboration, where VET teachers benefit from shared experiences and a support network that strengthens their professional identity and confidence. Zhou et al. (2022) and the Cedefop report (2022) also stress the value of peer learning within communities of practice, where mutual sharing and support are crucial for VET teachers’ professional growth and the practical application of acquired knowledge and skills. Additionally, a holistic framework for effective professional development should consider both individual and institutional factors. This includes addressing the specific needs of VET teachers by fostering a safe space for critical reflection and feedback within professional communities, establishing a supportive learning environment, and promoting transformative leadership in VET institutions as learning communities (Siliņa-Jasjukeviča et al., 2024).

Providing VET teachers with greater autonomy in defining their professional development needs and actively engaging in new learning experiences further supports the effective transfer of learning to practice. Increased autonomy reinforces teachers’ responsibility to apply the knowledge and skills acquired through professional development, thereby enhancing the quality of their teaching. Beyond autonomy, teacher agency plays a crucial role in professional development and its effective transfer to practice. Agency refers to teachers’ ability to make intentional choices and take actions to influence their learning environments and professional growth, even within externally imposed constraints (Priestley et al., 2015). Exercising agency enables VET teachers not only to participate in professional learning but also to actively shape the way they integrate new knowledge and practices into their teaching, ensuring that professional development outcomes are meaningful and sustainable.

For professional training to be truly effective, all aspects of formal, informal, and non-formal education should be considered, ensuring that teachers find both personal and professional value in their professional development. According to Siliņa-Jasjukeviča et al. (2024), VET teachers’ professional development should be seen more broadly, encompassing relationships with students, colleagues, administration, social partners, and their role within the school as a learning organisation. In such a learning organisation, teachers see themselves as part of a wider system where the success of the organisation relies on the professional performance of each member. Thus, creating and supporting continuous learning opportunities, promoting team learning and collaboration, and learning with and from the external environment within communities of practice are all integral to fostering a culture of mutual learning and support in these learning organisations.

A recent systematic literature review on the experiences of VET teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic highlights the importance of teachers’ compassion, humanity, innovation, and resilience, which are necessary qualities in times of crisis (Nakar & Trevarthen, 2024). The personality traits such as resilience, creativity, collaboration, and friendship are essential for quickly and flexibly acquiring new competences to meet the needs of students in times of uncertainty.

In relation to existing research on teachers’ professional development more broadly, the findings confirm several well-established features of effective professional development, such as the importance of reflection, collaboration within communities of practice, alignment with teachers’ needs, as emphasised in previous studies (Sims & Fletcher-Wood, 2021; Sims et al., 2021; Sims et al., 2025). However, this study also offers a more nuanced understanding of how these characteristics manifest specifically within the context of VET. For instance, the dual professional identity of VET teachers—as both educators and occupational practitioners—creates distinct demands for professional development that supports not only pedagogical enhancement but also the maintenance of occupational expertise. Professional development in VET is more effective when it acknowledges and supports this dual identity, as VET teachers are motivated not solely by pedagogical improvement but also by the need to remain relevant and credible within their industry. While peer collaboration within teachers’ learning communities is widely recognised as valuable in the general professional development literature, VET teachers particularly benefit from collaboration with social partners and industry professionals. This expands the traditional notion of internal professional learning communities into broader, cross-sectoral networks. Furthermore, the effective transfer of learning into practice within the VET context requires targeted support mechanisms that reflect the complexities of teaching in dual-context environments (educational and industry).

5. Conclusions

Effective professional development (PD) for vocational education and training (VET) teachers is a complex, multidimensional process that must be tailored to the specific needs, contexts, and resources of different institutions. A uniform approach is impractical, as VET teachers require distinct educational support compared to general subject teachers, including a focus on industry relevance, hands-on expertise, and connections with sector experts. For optimal impact, professional development should empower VET teachers with autonomy in decision making, foster collaboration through communities of practice, and strengthen ties with industry to enhance educational quality and teacher professionalism.

Professional development in VET must balance educational priorities with industry needs, helping teachers cultivate a “dual identity” as both educators and field specialists. This dual role enables VET teachers to bridge academic content with real-world applications, ensuring their skills and knowledge remain current and industry relevant. Managers in VET institutions should adopt a flexible, nuanced approach to supporting professional growth, offering resources, time, and opportunities for reflection, collaboration, and problem-solving aligned with these dual responsibilities.

The quality of professional development also depends significantly on the calibre of training providers and the relevance of programme content. Trainers must possess expertise in both pedagogy and their respective industries, delivering training that equips VET teachers with contemporary skills and insights into sector innovations. This demand aligns with the need for a flexible, balanced, and continuous approach to professional development that covers not only technical competencies but also fosters a culture of lifelong learning.

Professional development programmes should address needs at the micro (individual), meso (institutional), and macro (policy) levels. At the micro level, personalised training that directly aligns with VET teachers’ roles and motivations can enhance engagement and learning outcomes. At the meso level, institutional support—such as fostering a strong organisational learning culture—is essential to reinforce continuous professional growth. At the macro level, policy frameworks can provide the infrastructure and standards necessary to sustain professional development across the sector.

Professional development should not be limited to isolated workshops or courses but should encompass ongoing, diverse learning experiences across multiple contexts, including workplace environments. Cultivating an organisational culture that prioritises learning benefits all staff and reinforces the link between professional development and institutional success.

Currently, many studies tend to focus predominantly on the professional development needs of early-career VET teachers, often overlooking those in mid- and late-career stages. Effective professional development must cater to teachers across all career phases, providing tailored support, resources, and motivational strategies to encourage sustained engagement in professional growth. This approach ensures that teachers, regardless of experience, feel valued and empowered to contribute meaningfully to their fields.

Broadening the scope of professional development to include relational dimensions—such as collaboration with students, colleagues, and external partners—positions VET teachers more effectively within their institutions as integral members of a learning organisation. This holistic view acknowledges the multifaceted nature of VET teaching, where continuous learning, flexibility, and responsiveness are essential for professional excellence.

In summary, this review highlights that effective professional development for VET teachers must be industry-aligned, collaborative, and based on active learning processes. Reflection, engagement in communities of practice, and attention to teachers’ needs are critical to successful professional development and its transfer into practice. Facilitating the transfer of professional development outcomes requires institutional support, authentic work-based learning environments, and transformative practices. These elements enable VET teachers to meet evolving industry demands and provide students with relevant, high-quality education. Tailored, flexible approaches to professional development are essential for supporting the lifelong growth of VET teachers and ensuring their adaptability within a dynamic and changing professional landscape.

The findings of this review suggest several implications for the design and implementation of VET teacher professional development programmes. Professional development activities should be embedded within authentic, practice-based settings that reflect the realities of vocational work environments. Strengthening partnerships between educational institutions and industry stakeholders is crucial to enhancing the relevance and transferability of the knowledge and skills acquired. Moreover, fostering collaborative professional learning communities can support critical reflection, professional identity development, and sustained practice improvement. Establishing long-term mentorship structures and peer-support mechanisms is equally important to facilitate the ongoing transfer of learning into everyday teaching practices.

Building on the findings of this study, several areas merit further investigation. Future research should explore how VET teachers apply new knowledge in practice, particularly as they transition into different career stages, with case studies and practical examples offering valuable insights into the real-world impacts of professional development. Longitudinal studies are needed to examine the long-term sustainability of professional development outcomes and the durability of practice changes across varied VET contexts. Investigating the role of VET teachers’ professional agency in the transfer of learning, and how agency interacts with institutional environments, represents another promising avenue for research. Furthermore, incorporating non-English literature and cross-cultural comparisons would broaden the understanding of professional development dynamics in diverse educational systems. Finally, examining how organisational cultures and leadership practices within VET institutions influence the effectiveness and transferability of professional development initiatives would provide important contributions to the field.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, G.S.-J. and S.S.; methodology, G.S.-J. and S.S.; validation, G.S.-J. and S.S.; formal analysis, G.S.-J., I.L.-E. and D.I.; investigation, G.S.-J., D.I. and S.S.; resources, G.S.-J., I.L.-E., D.I. and S.S.; data curation, G.S.-J., I.L.-E. and S.S.; writing—original draft preparation, G.S.-J., I.L.-E., D.I. and S.S.; writing—review and editing, G.S.-J., I.L.-E. and S.S.; visualisation, I.L.-E. and S.S.; supervision, G.S.-J., I.L.-E. and S.S.; project administration, S.S.; funding acquisition, G.S.-J., I.L.-E. and S.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is funded by the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Latvia, project “Elaboration of evidence-based solutions for effective professional competence development of adults and assessment of the transfer of its results into practice in Latvia”, project No. VPP-IZM-Izglītība-2023/4-0001.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Inter-Rater Reliability Test Results (Cohen’s Kappa).

Table A1.

Inter-Rater Reliability Test Results (Cohen’s Kappa).

| Study | Cohen’s Kappa Value | Sig. | Agreement (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Andersson et al. (2018) | 1.000 | 0.000 | 100 |

| Andersson and Köpsén (2018) | No statistics are computed because is a constant. | ||

| Andersson and Köpsén (2019) | 1.000 | 0.000 | 100 |

| Antera (2022) | 1.000 | 0.000 | 100 |

| Ballangrud and Nilsen (2021) | 1.000 | 0.000 | 100 |

| Beverborg et al. (2015) | 0.771 | 0.001 | 77 |

| de Paor (2018) | 0.865 | 0.000 | 87 |

| Dymock and Tyler (2018) | 1.000 | 0.000 | 100 |

| Gagnon and Dubeau (2023) | 1.000 | 0.000 | 100 |

| Hommel et al. (2023) | 1.000 | 0.000 | 100 |

| Jin et al. (2021) | 0.759 | 0.001 | 76 |

| Köpsén and Andersson (2017) | 1.000 | 0.000 | 100 |

| Njenga (2023) | 1.000 | 0.000 | 100 |

| Sandal (2023) | 1.000 | 0.000 | 100 |

| Sappa et al. (2016) | 1.000 | 0.000 | 100 |

| Schmidt (2019) | 0.620 | 0.001 | 62 |

| Serafini (2018) | 0.779 | 0.000 | 78 |

| Smith and Tuck (2023) | 1.000 | 0.000 | 100 |

| Smith and Yasukawa (2017) | 0.822 | 0.000 | 82 |

| Tran and Pasura (2021) | 1.000 | 0.000 | 100 |

| Tyler and Dymock (2019) | 1.000 | 0.000 | 100 |

| Zeggelaar et al. (2018) | 1.000 | 0.000 | 100 |

| Zeggelaar et al. (2022) | 1.000 | 0.000 | 100 |

| Zhang et al. (2022) | 1.000 | 0.000 | 100 |

Appendix B

Table A2.

Brief Overview of Selected Publications.

Table A2.

Brief Overview of Selected Publications.

| No | Author/s, Year | Study Location | Type of Research, Research Methods | Sample | The Aim of the Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Andersson et al. (2018) | Sweden | Empirical research/survey/quantitative data analysis | 886 | To analyse the participation of VET teachers in various types of professional development activities aimed at making teachers more knowledgeable about innovations in the field. |

| 2. | Andersson and Köpsén (2018) | Sweden | Empirical research/survey/quantitative data analysis | 886 | To study the factors affecting values in relation to the professional development of VET teachers. |

| 3. | Andersson and Köpsén (2019) | Sweden | Empirical research/semi-structured interviews/qualitative data analysis | 30 | To explore the interaction between school and working life and how it relates to the renewal of VET teachers’ professional competence and identity formation. |

| 4. | Antera (2022) | Sweden | Empirical research/semi-structured interview/qualitative data analysis | 14 | To find out how the competence of VET teachers is perceived by Swedish VET teachers, while mapping the professional competence of VET teachers and its relationship with their daily learning activities. |

| 5. | Ballangrud and Nilsen (2021) | Norway | Empirical research/semi-structured interviews/qualitative data analysis | 9 | To explore interactions in various professional development activities in which VET teachers are involved in order to enrich their professional knowledge. |

| 6. | Beverborg et al. (2015) | Netherlands | Empirical research/survey/quantitative data analysis | 447 | To explore the role of organisational and psychological factors in stimulating teachers’ learning. |

| 7. | de Paor (2018) | Ireland | Empirical research/focus group discussions/qualitative data analysis | 6 | To explore the professional development needs of teachers in relation to the results of the Erasmus+ strategic partnership QUAKE, focused on the professional development of teachers and ECVET mobility of learners in several European countries. |

| 8. | Dymock and Tyler (2018) | Australia | Theoretical research/literature analysis | - | To analyse professional development approaches used in other professions and to identify key features in order to develop a more purposeful and systematic organisation of a continuous learning for the VET teachers. |

| 9. | Gagnon and Dubeau (2023) | Canada | Empirical research/semi-structured interview/qualitative data analysis | 21 | To explore how novice VET teachers develop and maintain their self-efficacy through strategies related to (1) academic work, (2) resource mobilisation, (3) professional development, and (4) attitudes and well-being at work to gain a deeper understanding of previously unexplored aspects of reality by novice VET teachers and suggest ways to design interventions that are aimed to meet their needs. |

| 10. | Hommel et al. (2023) | Germany | Empirical research/interview/qualitative data analysis | 8 | To develop a conceptual model of reflection that is appropriate for meeting the professional needs of VET teachers, deriving from different perspectives and integrating them into one model. |

| 11. | Jin et al. (2021) | China | Empirical research/semi-structured interview/qualitative data analysis | 4 | To explore the cooperation of novice teachers and teacher experts in the process of professional development. |

| 12. | Köpsén and Andersson (2017) | Sweden | Empirical study/quantitative analysis of state register data | 981 | To explore the participation of VET teachers in a new national professional development initiative in Sweden. The article specifically examines the model of repeated participation of VET teachers in the professional development offer. |

| 13. | Njenga (2023) | Kenya | Empirical research/survey/quantitative data analysis | 170 | To explore professional development practices of VET teachers in Kenya by analysing formal and informal learning methods used. |

| 14. | Sandal (2023) | Norway | Empirical research/focus group discussion/qualitative data analysis | 28 | To analyse how the professional development course “Assessment in vocational education” (15 credits) contributes to a professional development of VET teachers and its transfer to practice. |

| 15. | Sappa et al. (2016) | Switzerland, Australia | Empirical research/semi-structured interview/qualitative data analysis | 15 | To explore the perceptions of students, teachers, instructors, and managers/coordinators about the interconnection of learning implemented in the school and work environment. |

| 16. | Schmidt (2019) | Australia | Empirical research/semi-structured interview/qualitative data analysis | 35 | To explore the competence of VET teachers in pedagogy. |

| 17. | Serafini (2018) | Italy, Australia, Denmark, Finland, Mexico, Poland | Empirical research/survey/quantitative data analysis | 25,300 | To quantify, qualify, and internationally compare a set of key indicators that can be used in a comparative perspective to characterise the existing professional development system of VET teachers in Italy, to report on further steps in its improvement, as well as to promote research and policy debates in this field at the national and international levels. |

| 18. | Smith and Tuck (2023) | Australia | Empirical research/survey/quantitative data analysis | 1255 | To investigate how teaching practices and teaching approaches of VET teachers change depending on their qualification level. |

| 19. | Smith and Yasukawa (2017) | Australia | Empirical research/focus group discussion/qualitative data analysis | 69 | To find out what is “good development of professional competence” and what is needed to ensure it? |

| 20. | Tran and Pasura (2021) | Australia | Empirical research/observation and semi-structured interview/qualitative data analysis | 120 | To find out how to improve the professional competence of VET teachers to match the work with international students by respecting their needs. |

| 21. | Tyler and Dymock (2019) | Australia | Empirical research/semi-structured interview/qualitative data analysis | 26 | To investigate the perceptions of VET teachers about the impact of continuous professional development on knowledge in the profession and pedagogy. |

| 22. | Zeggelaar et al. (2018) | The Netherlands | Empirical research/mixed methods/qualitative and quantitative data analysis | 39 | To explore opportunities for improving the quality of a professional development by assessing which professional development strategies are the most effective. |

| 23. | Zeggelaar et al. (2022) | The Netherlands | Empirical research/mixed methods/qualitative and quantitative data analysis | 39 | To determine the requirements for the development of effective professional development programmes for VET teachers |

| 24. | Zhang et al. (2022) | China | Empirical research/test/quantitative data analysis | 601 | To investigate the factors that affect the professional competence of VET teachers. |

Appendix C

Table A3.

Characteristics of the Effective Professional Development of VET Teachers.

Table A3.

Characteristics of the Effective Professional Development of VET Teachers.

| Characteristics | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Systematic and Targeted Professional Development | Considering VET Teachers’ Needs | Maintaining Connections with Industry | Mentoring | Reflection and Self-Reflection | Engagement in Communities of Practice | Cooperation with Social Partners | Guidance and Feedback | Learning Through Active Participation | Tailored to the Local Context | Total of References per Study |

| Andersson et al. (2018) | • | • | • | 3 | |||||||

| Andersson and Köpsén (2018) | • | • | • | 3 | |||||||

| Andersson and Köpsén (2019) | • | • | • | 3 | |||||||

| Antera (2022) | • | • | • | • | • | • | 6 | ||||

| Ballangrud and Nilsen (2021) | • | • | • | • | 4 | ||||||

| Beverborg et al. (2015) | • | • | • | • | • | 5 | |||||

| de Paor (2018) | • | • | 2 | ||||||||

| Dymock and Tyler (2018) | • | • | 2 | ||||||||

| Gagnon and Dubeau (2023) | • | • | • | • | • | 5 | |||||

| Hommel et al. (2023) | • | 1 | |||||||||

| Jin et al. (2021) | • | • | • | • | 4 | ||||||

| Köpsén and Andersson (2017) | • | • | 2 | ||||||||

| Njenga (2023) | • | • | • | 3 | |||||||

| Sandal (2023) | • | • | • | • | 4 | ||||||

| Sappa et al. (2016) | • | • | • | 2 | |||||||

| Schmidt (2019) | • | • | • | • | 4 | ||||||

| Serafini (2018) | • | • | 2 | ||||||||

| Smith and Tuck (2023) | • | • | 2 | ||||||||

| Smith and Yasukawa (2017) | • | 1 | |||||||||

| Tran and Pasura (2021) | • | • | 2 | ||||||||

| Tyler and Dymock (2019) | • | • | • | • | 4 | ||||||

| Zeggelaar et al. (2018) | • | • | • | 3 | |||||||

| Zeggelaar et al. (2022) | • | 1 | |||||||||

| Zhang et al. (2022) | • | • | • | 3 | |||||||

| Total number of studies | 3 | 5 | 18 | 2 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 2 | 13 | 2 | |

Note: The dot symbol (•) indicates that the study provided evidence or discussion relevant to the corresponding category of effective professional development of VET teachers.

Appendix D

Table A4.

Characteristics That Support the Effective Transfer of VET Teachers’ Professional Development.

Table A4.

Characteristics That Support the Effective Transfer of VET Teachers’ Professional Development.

| Characteristics | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Teachers’ Capacity and Performance | Transformative Experience to Change Practice | Engagement in Communities of Practice and Peer Support | Reflection on Current Practices | Personally Meaningful Experience | Transformative Leadership | Management Support and Investment in Teachers’ Professional Development, Considering Teachers’ Needs | Authentic Learning in the Work Environment | Total of References per Study |

| Andersson et al. (2018) | • | • | • | 3 | |||||

| Andersson and Köpsén (2018) | • | 1 | |||||||

| Andersson and Köpsén (2019) | • | • | 2 | ||||||

| Antera (2022) | • | • | • | • | 4 | ||||

| Ballangrud and Nilsen (2021) | • | • | • | • | 4 | ||||

| Beverborg et al. (2015) | • | • | • | • | • | 5 | |||

| de Paor (2018) | • | • | • | 3 | |||||

| Dymock and Tyler (2018) | • | • | • | • | 4 | ||||

| Gagnon and Dubeau (2023) | • | • | • | 2 | |||||

| Hommel et al. (2023) | • | • | • | • | 4 | ||||

| Jin et al. (2021) | • | • | • | 3 | |||||

| Köpsén and Andersson (2017) | • | • | 2 | ||||||

| Njenga (2023) | • | • | • | • | • | 5 | |||

| Sandal (2023) | • | 1 | |||||||

| Sappa et al. (2016) | • | • | 2 | ||||||

| Schmidt (2019) | • | 1 | |||||||

| Serafini (2018) | • | • | • | 3 | |||||

| Smith and Tuck (2023) | • | 1 | |||||||

| Smith and Yasukawa (2017) | • | 1 | |||||||

| Tran and Pasura (2021) | • | • | 2 | ||||||

| Tyler and Dymock (2019) | • | • | • | • | 4 | ||||

| Zeggelaar et al. (2018) | • | • | • | 3 | |||||

| Zeggelaar et al. (2022) | • | • | • | 3 | |||||

| Zhang et al. (2022) | • | 1 | |||||||

| Total number of studies | 4 | 4 | 15 | 8 | 7 | 2 | 14 | 11 | |

Note: The dot symbol (•) indicates that the study provided evidence or discussion relevant to the corresponding category related to supporting the effective transfer of VET teachers’ professional development.

Appendix E. Main Characteristics of Effective VET Teachers’ Professional Development and Its Transfer into Practice (Identified Through Thematic Analysis of 24 Studies)

References

- Anderson, S. E. (1997). Understanding teacher change: Revisiting the concerns based adoption model. Curriculum Inquiry, 27(3), 331–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, P., Hellgren, M., & Köpsén, S. (2018). Factors influencing the value of CPD activities among VET teachers. International Journal for Research in Vocational Education and Training, 5(2), 140–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, P., & Köpsén, S. (2018). Maintaining competence in the initial occupation: Activities among vocational teachers. Vocations and Learning, 11, 317–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, P., & Köpsén, S. (2019). VET teachers between school and working life: Boundary processes enabling continuing professional development. Journal of Education and Work, 32(6–7), 537–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antera, S. (2022). Being a vocational teacher in Sweden: Navigating the regime of competence for vocational teachers. International Journal for Research in Vocational Education and Training, 9(2), 269–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballangrud, B. B., & Nilsen, E. (2021). VET teachers continuing professional development—The responsibility of the school leader. Journal of Education and Work, 34(5–6), 691–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W. H. Freeman and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Beverborg, A. O., Sleegers, P. J., & van Veen, K. (2015). Fostering teacher learning in VET colleges: Do leadership and teamwork matter? Teaching and Teacher Education, 48, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeskens, L., Nusche, D., & Yurita, M. (2020). Policies to support teachers’ continuing professional learning: A conceptual framework and mapping of OECD data. OECD Education Working Papers, No. 235. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boylan, M., & Woolsey, I. (2015). Teacher education for social justice: Mapping identity spaces. Teaching and Teacher Education, 46, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canrinus, E. T., Helms-Lorenz, M., Beijaard, D., Buitink, J., & Hofman, A. (2011). Profiling teachers’ sense of professional identity. Educational Studies, 37(5), 593–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciraso, A. (2012). An evaluation of the effectiveness of teacher training: Some results from a study on the transfer factors of teacher training in Barcelona area. Procedia—Social and Behavioral Sciences, 46, 1776–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. (2024). CASP checklist for qualitative research. Available online: https://casp-uk.net/casp-checklists/CASP-checklist-qualitative-2024.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2024).

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, C. (2002). School reform and transitions in teacher professionalism and identity. International Journal of Educational Research, 37(8), 677–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Arco, I., Anabel Ramos-Pla, A., & Flores-Alarcia, Ò. (2023). Analysis of school principal training in Catalonia universities: Transfer to the practice of principals. School Leadership & Management, 43(5), 546–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Paor, C. (2018). Supporting change in VET: Teachers’ professional development and ECVET learner mobility. Empirical Research in Vocational Education and Training, 10(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dymock, D., & Tyler, M. (2018). Towards a more systematic approach to continuing professional development in vocational education and training. Studies in Continuing Education, 40(2), 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Development of Vocational Training. (2022). Teachers and trainers in a changing world: Building up competences for inclusive, green and digitalised vocational education and training (VET): Synthesis report. Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evidence for Policy and Practice Information Centre. (2003). Review guidelines for extracting data and quality assessing primary studies in educational research (Version 0.9.7). EPPI Centre, Social Science Research Unit. Available online: https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Default.aspx?tabid=184#Guidelines (accessed on 25 February 2024).

- Gagnon, N., & Dubeau, A. (2023). Building and maintaining self-efficacy beliefs: A study of entry-level vocational education and training teachers. Vocations and Learning, 15, 511–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, A. J., Mataveli, M., & Garcia-Alcaraz, J. L. (2022). Towards an analysis of the transfer of training: Empirical evidence from schools in Spain. European Journal of Training and Development, 46(5/6), 652–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guskey, T. R. (2000). Evaluating professional development. Corwin. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, G. E. (1974). The concerns-based adoption model: A developmental conceptualization of the adoption process within educational institutions. The Research and Development Center for Teacher Education, The University of Texas at Austin. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED111791.pdf (accessed on 17 February 2024).

- Hall, G. E., & Hord, S. M. (1987). Change in schools: Facilitating the process. State University of New York Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, G. E., & Hord, S. M. (2011). Implementing change: Patterns, principles and potholes (3rd ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Hommel, M., Fürstenau, B., & Mulder, R. H. (2023). Reflection at work—A conceptual model and the meaning of its components in the domain of VET teachers. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 923888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isna, N. (2021). A study of teacher development program on transfer of learning in Indonesia [Doctoral dissertation, Texas A&M University]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/docview/2668982939 (accessed on 25 February 2024).

- Jarvis, P. (1987). Adult learning in the social context. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, X., Li, T., Meirink, J., van der Want, A., & Admiraal, W. (2021). Learning from novice–expert interaction in teachers’ continuing professional development. Professional Development in Education, 47(5), 745–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, D. L. (1998). The four levels of evaluation. In S. M. Brown, & C. J. Seidner (Eds.), Evaluating corporate training: Models and issues. Evaluation in education and human services (pp. 95–112). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, D. L., & Kirkpatrick, J. D. (2006). Evaluating training programs: The four levels (3rd ed.). Berrett-Koehler Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Koay, J. (2023). Self-directed professional development activities: An autoethnography. Teaching and Teacher Education, 133, 104258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, M. J., Mishra, P., & Cain, W. (2013). What is technological pedagogical content knowledge (TPACK)? Journal of Education, 193(3), 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koehler, M. J., Mishra, P., Kereluik, K., Shin, T. S., & Graham, C. R. (2014). The technological pedagogical content knowledge framework. In J. Spector, M. Merrill, J. Elen, & M. Bishop (Eds.), Handbook of research on educational communications and technology (pp. 101–111). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köpsén, S., & Andersson, P. (2017). Reformation of VET and demands on teachers’ subject knowledge—Swedish vocational teachers’ recurrent participation in a national CPD initiative. Journal of Education and Work, 30(1), 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ley, T., Maier, R., Thalmann, S., Waizenegger, L., Pata, K., & Ruiz-Calleja, A. (2020). A knowledge appropriation model to connect scaffolded learning and knowledge maturation in workplace learning settings. Vocations and learning, 13(1), 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maomani, A. M. (2020). The unified theory of acceptance and use of technology: A new approach in technology acceptance. International Journal of Sociotechnology and Knowledge Development, 12(3), 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, J. (1989). Transformative learning and social action: A response to Collard and Law. Adult Education Quarterly, 39(3), 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezirow, J. (1991). Transformative dimensions of adult learning. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. J. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108(6), 1017–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakar, S., & Trevarthen, R. (2024). Investigating VET teachers’ experiences during and post COVID. Policy Futures in Education, 22(8), 1748–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njenga, M. (2023). How do vocational teachers learn? Formal and informal learning by vocational teachers in Kenya. International Journal for Research in Vocational Education and Training, 10(1), 24–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priestley, M., Biesta, G., & Robinson, S. (2015). Teacher agency: An ecological approach. Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Sandal, A. K. (2023). Vocational teachers’ professional development in assessment for learning. Journal of Vocational Education & Training, 75(4), 654–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sappa, V., Choy, S., & Aprea, C. (2016). Stakeholders’ conceptions of connecting learning at different sites in two national VET systems. Journal of Vocational Education & Training, 68(3), 283–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, T. (2019). Industry currency and vocational teachers in Australia: What is the impact of contemporary policy and practice on their professional development? Research in Post-Compulsory Education, 24(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoeb, G., Lafrenière-Carrier, B., Lauzier, M., & Courcy, F. (2021). Measuring transfer of training: Review and implications for future research. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences, 38(1), 17–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senge, P. M. (1994). The fifth discipline field book strategies and tools for building a learning organization. Currency Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Serafini, M. (2018). The professional development of VET teachers in Italy: Participation, needs and barriers. Statistical quantifications and benchmarking in an international perspective. Empirical Research of Vocational Education and Training, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siliņa-Jasjukeviča, G., Briška, I., Lūsēna-Ezera, I., Lastovska, A., & Linde, I. (2024). Implementation of the school as a learning organisation approach in vocational education: The case of Latvia. Acta Paedagogica Vilnensia, 52, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, S., & Fletcher-Wood, H. (2021). Identifying the characteristics of effective teacher professional development: A critical review. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 32(1), 47–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, S., Fletcher-Wood, H., O’Mara-Eves, A., Cottingham, S., Stansfield, C., Goodrich, J., Van Herwegen, J., & Anders, J. (2025). Effective teacher professional development: New theory and a meta-analytic test. Review of Educational Research, 95(2), 213–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sims, S., Fletcher-Wood, H., O’Mara-Eves, A., Cottingham, S., Stansfield, C., Van Herwegen, J., & Anders, J. (2021). What are the characteristics of effective teacher professional development? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Education Endowment Foundation. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED615914.pdf (accessed on 17 February 2024).

- Smith, E., & Tuck, J. (2023). Do the qualifications of vocational teachers make a difference to their teaching? Research in Post-Compulsory Education, 28(1), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, E., & Yasukawa, K. (2017). What makes a good VET teacher? Views of Australian VET teachers and students. International Journal of Training Research, 15(1), 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toepper, M., Zlatkin-Troitschanskaia, O., & Kühling-Thees, C. (2021). Research in international transfer of vocational education and training—A systematic literature review. International Journal for Research in Vocational Education and Training, 8(4), 138–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, L. H., & Pasura, R. (2021). The nature of teacher professional development in Australian international vocational education. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 45(1), 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, M., & Dymock, D. (2019). Maintaining industry and pedagogical currency in VET: Practitioners’ voices. International Journal of Training Research, 17(1), 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatesh, V., Thong, J. Y. L., & Xu, X. (2016). Unified theory of acceptance and use of technology: A synthesis and the road ahead. Journal of the Association for Information Systems, 17(5), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeggelaar, A., Vermeulen, M., & Jochems, W. (2018). Exploring what works in professional development: An assessment of a prototype intervention and its accompanying design principles. Professional Development in Education, 44(5), 750–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeggelaar, A., Vermeulen, M., & Jochems, W. (2022). Evaluating effective professional development. Professional Development in Education, 48(5), 806–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., Tian, J., Zhao, Z., Zhou, W., Sun, F., Que, Y., & He, X. (2022). Factors influencing vocational education and training teachers’ professional competence based on a large-scale diagnostic method: A decade of data from China. Sustainability, 14, 15871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N., Tigelaar, D., & Admiraal, W. (2022). Vocational teachers’ professional learning: A systematic literature review of the past decade. Teaching and Teacher Education, 119, 103856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, N., Tigelaar, D., Wang, J., & Admiraal, W. (2024). Factors predicting vocational teachers’ transfer of learning: A quantitative study in the context of work placement. Teaching and Teacher Education, 140, 104467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).