1. Introduction

From a classical perspective closely linked to linguistics, metaphor is conceived as a resource inherent to language itself. However, since

Lakoff and Johnson’s (

1980) seminal work, entitled

Metaphors of Everyday Life, metaphor has begun to be understood as intertwined between thought and action. According to

Gibbs (

2011), the fact that metaphors are common in various languages points to the fact that metaphors are conceptual and rooted in human action. Metaphor allows us to understand the unknown in terms of the known, enabling cognitive savings (

Banaruee et al., 2019). Sometimes, what is known is more accessible because it belongs to a representation modality more closely linked to the sensory or motor, which allows firsthand access. In these cases, in which the most well-known aspect of the metaphor is rooted in the corporeal, we are dealing with embodied metaphors. Embodied cognition is a theoretical approach that studies the situations in which humans construct concepts based on perceptual, motor, or interoceptive experiences (

de Vega, 2021;

Desai, 2022;

García & Ibañez, 2018;

Horchak et al., 2014;

Strick & Van Soolingen, 2018). In this sense,

Desai’s (

2022) review of several studies using neuroimaging techniques led to the conclusion that metaphors are based on or sourced from the sensorimotor.

In every metaphor, an unknown domain, called the target or source, is conceived in terms of another more familiar or accessible domain, called the source or base (

Colston & Gibbs, 2021). For example, there are studies that analyze how metaphor allows us to understand emotions, which constitutes a complex phenomenon, based on colors (

Fugate & Franco, 2019), although the metaphorical link between an emotion and a color is stronger or more deeply rooted in some cases than in others, as is the case with anger and red or joy and yellow, which have a stronger link than in cases such as sadness and the color blue (

Jonauskaite et al., 2020). Furthermore, interestingly, it is the dimensional aspect rather than the categorical aspect that is associated in some cases when metaphorizing an emotion with a color. For example, gray tends to be associated with negative, but weak, emotions, while black with stronger negative emotions (

Sutton & Altarriba, 2016). It is also interesting to associate good with light and bad with darkness (

Littlemore et al., 2023), both in religious and everyday contexts (

Sandford, 2021). Another example is when we use head and hand movements or upward gestures to accompany emotions such as anger, joy, or pride, and downward gestures when the emotions are sadness or shame (

Khatin-Zadeh et al., 2023). Also, when we want to express that we have been relieved of a stressful situation or the emotion of stress, we metaphorize it through body movements, such as exhaling air through the mouth, followed by a downward movement of the shoulders, another downward and frontal movement of the head and frontal movement of the hands (

Khatin-Zadeh et al., 2024). Or, simply, when we say that we face a situation with our head held high to refer to the fact that we do not have to be ashamed of something or, even, we can be proud of something we have done well. The emotion of disgust has also been used as a source domain—perhaps because it constitutes a basic emotion and, therefore, is more accessible—to metaphorize attitudes or actions morally considered unjust. This metaphor is highlighted in the study by

Chapman et al. (

2009), who asked participants to play a game in which coins were distributed. Sometimes, a study participant’s opponent took advantage of them and gave them fewer coins. Participants more often displayed facial expressions of disgust in response to these unfair distributions of money. Specifically, the levator labii muscle was activated, the same muscle that is typically activated by photographs of contaminating stimuli and unpleasant tastes. This indicates that the emotional response to disgust-inducing stimuli also appears to occur when stimuli produce this type of indignation or moral rejection. Another socio-emotional metaphor relates social exclusion to pain.

MacDonald and Leary (

2005) also found, in various languages, terms applied to situations of social exclusion, expressed in terms such as “damage”, “wound”, and “blow”, as well as their respective verbs. Similarly, another way of corporatizing social exclusion is in terms of temperature, with heat constituting an important function in social cognition (

Herranz-Hernández & Naranjo-Crespo, 2023;

Izjerman & Semin, 2009;

Semin & Garrido, 2012). Support for this metaphor has also been found from a neuroscientific perspective (

Balter, 2007;

Eisenberger et al., 2003;

Insel & Young, 2001;

Kross et al., 2007;

Meyer-Lindenberg, 2008).

In the classroom context,

Newland et al. (

2019) attempted to study how students felt in the classroom. To undertake this, they used seasonal metaphors. Specifically, they considered two common aspects in the study of emotion: arousal and affective valence. Thus, they found that emotions related to safety or satisfaction had low arousal and positive valence; those related to excitement or fun were linked to the summer metaphor, with positive valence and high arousal. In the case of the autumn metaphor, it was related to emotions such as frustration or irritation, which had low arousal and negative valence. Finally, the winter metaphor was associated with high arousal, along with negative valence, and characterized emotions such as fear, anxiety, and anger.

Therefore, the main hypothesis of this study is to consider whether the embodied metaphor that conceives guilt in terms of dirt or hygiene could influence empathy toward someone else who has committed an undesirable act. If so, this would have implications for education, especially in relation to the development of emotional and social competencies for students, but also for preservice teachers.

In the psychological literature, the McBeth effect has been popularized as the metaphorization of guilt as filth or moral indignation as disgust (

Cuetos et al., 2015). It is in honor of Lady McBeth, the protagonist of Shakespeare’s play of the same name, who, after committing murder, felt the compulsive need to continually wash her hands. In this regard,

Zhong and Liljenquist (

2006) asked their participants to copy a comic strip. This comic strip could depict morally desirable or undesirable behavior. After copying this comic strip, they were asked to judge the desirability of certain products: some were cleaning products and others were non-cleaning products. They found that when participants had to copy the comic strip that described the most immoral behavior, they rated the cleaning products as more desirable. However, in this study, participants were asked to judge this desirability after copying the comic strip. This desirability was assessed, so to speak, in the first person, on a personal level. That is, they were asked to rate how desirable they found these products (cleaning or other) to themselves. However, it is worth asking whether when other people engage in more or less morally desirable behaviors, we can project this desirability onto others. That is, whether this metaphorization of moral guilt in terms of embodied dirt can be applied when judging the behavior of others. That is, whether we apply or transfer the McBeth effect to the other person who has acted ethically wrong, implicitly attributing this need for moral cleansing to others. If so, this would imply a form of empathy or putting oneself in the other’s place in terms of embodied and moral metaphorization, or even through said metaphorization as a means of empathizing. This would imply a way of taking into account, even if only implicitly, that others must feel, so to speak, dirty when they have engaged in some morally reprehensible or outrageous behavior.

Translated to the educational level, in this sense, teachers’ ability to empathize with their students could be improved. This is essential because this skill fosters a safe learning environment (

Stunell, 2021), promotes the elimination of exclusionary attitudes and a culture of diversity (

Beasy et al., 2020;

Symeonidou, 2017), and establishes bonds based on responsibility and respect (

Borremans & Spilt, 2022). In this sense, for example,

Crispel and Kasperski (

2021) found that when preservice teachers receive instruction in skills such as empathy, among others, they are more supportive and understanding of their students and are more accepting of diversity. Furthermore, they suggest that empathy, understood as the ability to understand another person, favors the creation of environments in which students feel understood and, therefore, increases their degree of participation and well-being, which is key to inclusive education. Understanding the other better morally represents a form of socio-emotional approach that favors inclusion, given that, as

Cabrera-Vázquez et al. (

2022) point out, when levels of moral sensitivity and empathy are adequate, teachers will adopt a position of greater acceptance of diversity.

All of this would be in line with the guidelines of the

European Agency for Special Needs Education and Inclusive Education (

2011), which establish that teachers must receive training that qualifies them to work in diverse classrooms. It is also important for promoting inclusive education. In Spain, first the Organic Law on Education (LOE) (

España, 2006) and, subsequently, the Organic Law for the Improvement of Educational Quality (LOMLOE) (

España, 2020) emphasized the importance of ensuring inclusive education. These laws sought to eliminate the barriers that hinder full student participation. And although this recent legislation in Spain presented an opportunity to restructure the Spanish education system, on a day-to-day basis, in the classroom, challenges remain regarding the achievement of truly inclusive education.

Thus, despite the fact that Spain committed to inclusive education three decades ago, at the Salamanca Conference (

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 1994), in order to move from mere integration to true inclusion, since then there have been contradictions and ambiguities between what the laws established and the effective reality in classrooms, so there has not been sufficient progress towards inclusion, as evidenced by the study by

Márquez and Fuentes (

2023). For example, educational centers still face difficulties, such as limited teacher training in inclusive education, a rigid curriculum, and little mutual collaboration between leaders and educational agents (

Andrews et al., 2021;

Márquez & Fuentes, 2023). Thus, in relation to the first aspect, it is highlighted that limiting conceptions persist among teachers regarding the capabilities of students with specific needs or regarding their ethnic diversity (

Mihić et al., 2022). In other words, legislative changes are not enough; they are necessary, but not sufficient. Furthermore, a transformation of teachers’ beliefs about diversity is required (

Navarro Mateos et al., 2021). However, this is not enough; teachers’ socio-emotional skills must also be strengthened, since these skills can be taught and the progress of inclusive education requires teachers to acquire social skills (

Stamatović et al., 2019). These skills promote the development of prosocial behavior that fosters respect for diversity and acceptance of others (

Hassanein et al., 2021).

On the other hand, in the school setting, there are relationships between the emotional competence of teachers and students and improvements in the classroom climate (

Iglesias-Díaz & Romero-Pérez, 2021). When this environment is positive, it improves children’s emotional well-being (

Aldridge et al., 2018;

Kurt, 2017;

Simmons et al., 2015). The interaction between students’ well-being and the school climate occurs in both directions, influencing each other (

Lawler et al., 2017). Therefore, it would be expected that work dedicated to improving emotional competence would improve the school climate. In fact, emotional intervention programs provide advantages such as reducing conflict and violence, helping to cope with depression or stress, and improving social participation and self-esteem, in addition to academic performance and development (

Araque, 2017).

For all these reasons, if the metaphor that links guilt with dirt or hygiene encourages putting oneself in the other’s shoes, in this case by projecting their desire to clear their guilt, we will be fostering empathic competence in future teachers, which is essential for an inclusive attitude, given that, as has been shown, the most common approach in the training programs initially received by future teachers does not guarantee that aspects such as empathy, among others, are sufficiently worked on (

Márquez & Moya, 2024). In short, if the metaphor allows us to understand the most inaccessible, difficult concepts in terms of something more accessible and firsthand, and if we consider that knowing the other, empathizing with them, etc., is more inaccessible to us than accessing ourselves, our own self, we would expect that the metaphor, as a bridge that allows us to access the unknown in terms of the known, also allows us to access the other, who is more unknown to us than ourselves, and empathize with them. Thus, metaphor could serve to bring us emotionally closer to others from within our own selves. By metaphorizing an emotion like guilt or indignation with disgust or hygiene, we can project ourselves onto others, facilitating our understanding of their emotions and their personalities, and thus fostering a more inclusive environment.

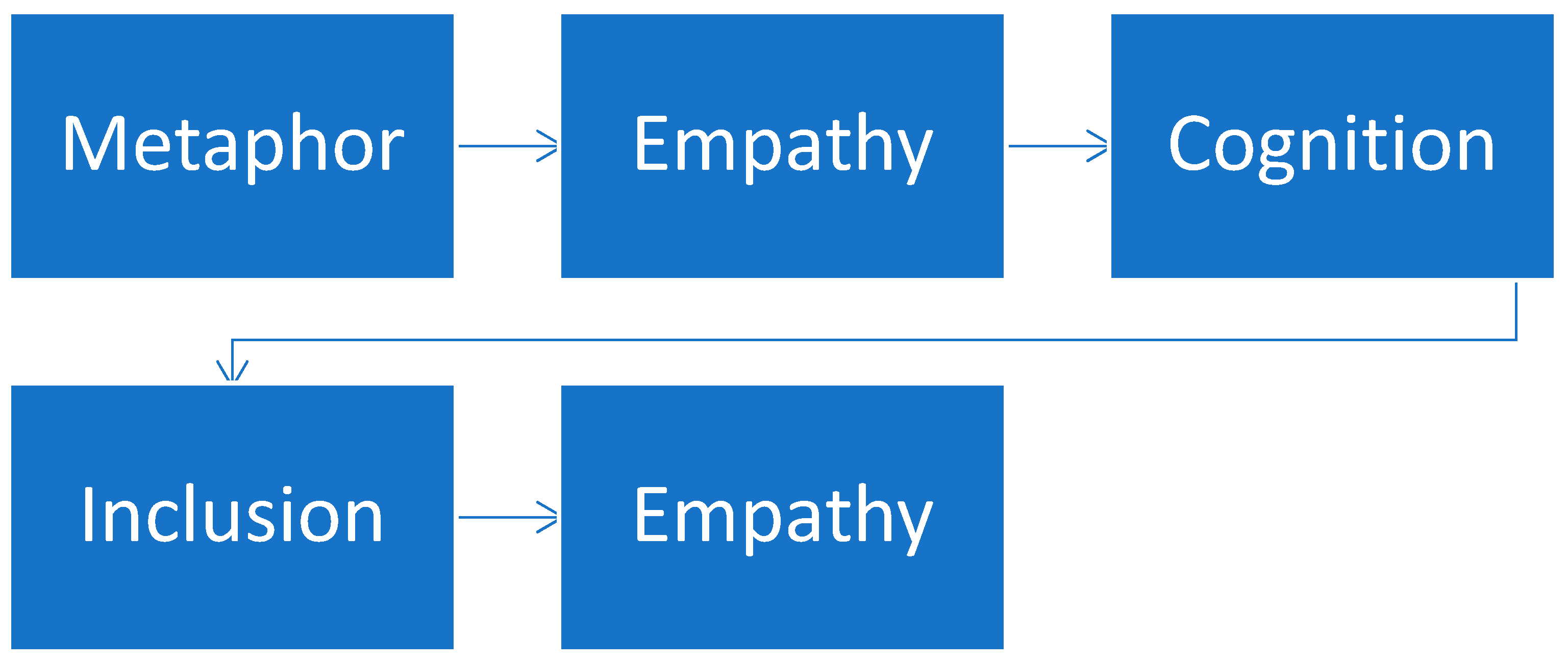

If so, this would have educational implications by allowing metaphor to enter the network of relationships between empathy, cognition, and inclusion. The latter could recursively reverse empathy, once again, by fostering an inclusive climate of emotional well-being and empathy, as noted above. Not all influences would necessarily have to go in the same direction. For example, cognition could also influence empathy (

Figure 1).

For all these reasons, the present study aims to examine this possible socio-moral projection of the metaphor that relates guilt with dirt or hygiene, but applied or projected to other agents and not to oneself, in order to examine the possible educational implications of said projection. To this end, a paradigm based on that of

Zhong and Liljenquist (

2006) will be used, but with some modifications in order to be able to examine this aspect of metaphorization projected towards others rather than oneself. Thus, as described in the procedure, the task was contextualized through a text in which participants had to assess the desirability of cleaning products or other products towards another protagonist who, in some cases, was engaging in prosocial behavior, and in others was rather selfish.

2. Materials and Methods

Fifty-seven students from the Faculty of Education at the Complutense University of Madrid participated in the study. Of these, 50 were women and 7 were men, ranging in age from 18 to 26 years (M = 20.37; SD = 1.87). Of the participants, 26 (45.61%) were students of the Degree in Teaching in Early Childhood Education, 25 (43.86%) of the Degree in Teaching in Primary Education, and 6 were studying the Double Degree in Teaching in Early Childhood and Primary Education (10.53%). Their collaboration was requested in faculty classrooms, and those interested in participating were convened in a large classroom. Therefore, their participation was voluntary. For this reason, mainly, a larger sample size, which would have been desirable, was not available. Furthermore, due to the higher prevalence of female than male students in the Faculty of Education at the aforementioned university, there was a significant difference in the number of men and women who participated. As this was a non-interventional study, involving the administration of a questionnaire with questions about a text describing a hypothetical situation involving a character, participants were informed that their participation in the study was completely anonymous and that the results would be processed solely for statistical purposes, preserving the privacy of their data. However, no personal information was requested, except for age, sex, and education. Participants signed an informed consent form. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This research is a non-interventional study that guarantees the anonymity of the participants in accordance with the Spanish Organic Law 3/2018 of 5 December on Data Protection and Guarantee of Digital Rights.

The design was experimental, with two experimental conditions (help condition versus exploitative condition), following a between-subjects design. The dependent variable was the mean scores given by participants for each gift category (gifts related to cleaning and hygiene versus gifts belonging to the “other” category). The reason why an experimental design was carried out is because we intended to analyze the possible relationships of causal influence between the blame attributed to others and the possible need to clean up, compared to situations in which that blame would not be attributed to others, but rather the opposite.

Once the participants were in the classroom, they were told that the study they were about to participate in was experimental. They were also informed that their task consisted of reading a text and answering written questions related to the text they had read. After being informed that their data would be treated statistically and confidentially, each participant was given a sheet of paper containing the study material. The sheet had writing on both sides. Since the study consisted of two experimental conditions, participants were randomly assigned one type of sheet or the other depending on the experimental condition. To undertake this random assignment, the booklets or packets of paper were mixed together and presented face down so that participants saw only the last blank sheet when they chose the booklet they wanted. Thus, each participant did not know which experimental condition they had been assigned to. All sheets, regardless of the experimental condition, contained a first section containing brief instructions. These instructions stated that they had to read a text and then answer a question. They were also informed in writing that their data would be treated confidentially for statistical purposes only. They were also thanked for their cooperation in writing in this brief paragraph.

Just below this paragraph was a section for participants to fill in the following personal information: sex, age, education, and grade level. Below this was a short paragraph consisting of two sentences, indicating that participants should first read the following text, which they could read as many times as they liked. The text appeared directly below this information. Depending on the experimental condition, one text or the other could appear of the two possible conditions. One experimental condition was the help condition, and the other the exploitative condition. In the help condition, the text began by telling participants to imagine working in an office with several colleagues. Pedro, a new colleague who is not yet fully familiar with his duties, has just joined the company. Luis, another colleague, although under no obligation to do so, helps Pedro get through his work to facilitate his integration and adaptation to the position. In another paragraph, the text said that next week is Luis’s birthday, and that among his colleagues, it is customary to pool money and buy low-cost gifts for colleagues celebrating their birthdays. The text also indicated that the participants would each receive a list of 10 possible gifts, and that they would rate each gift based on its suitability or appropriateness. It also stated that after each participant had rated each gift, the gifts that were most highly valued by all participants would be purchased. A brief paragraph later stated that participants should keep in mind that each of the possible gifts costs approximately the same amount of money.

In the experimental exploitation condition, the text was similar in length and grammatical and semantic complexity, although some aspects were modified in the first paragraph. For example, the text also began by instructing the participant to imagine working in an office with several coworkers and that Pedro, who is not yet familiar with his duties, has also joined. Luis is also mentioned, but this time with the difference that Luis takes advantage of Pedro. He tricks him into getting ahead in his own work, thus making it appear that Luis is very productive and allowing him to advance in his career. The following paragraph, which discusses the birthday, the custom of giving gifts, and the list of possible gift ratings, remained identical to the other experimental condition.

In both experimental conditions, the same written information also appeared below, as follows. First, another paragraph indicated that the participant had to rate the degree to which each gift seemed inappropriate or appropriate. To undertake this, they had to select the value on the scale that they considered best reflected the inappropriateness or appropriateness of the gift, circling the value or level they considered for each gift on the corresponding scale. Directly below this paragraph, the name of each gift appeared, and below each name, a table with one row and seven cells. Each cell indicated a qualitative description of each level, and directly below it, the number that recorded the numerical value of that level. From left to right, the cells contained the following:

The gifts that appeared, each with its own rating scale table below the name of each gift, were the following, in this order:

Post-it note pad

Bath soap

Juice

Toothpaste

Batteries

Window cleaner

CD-ROMs for burning

Disinfectant spray

Chocolates

Detergent

Once the participants circled their rating for each potential gift, they returned the sheet, thus completing their participation in the study. When they had submitted the materials, they were asked whether they had received any explicit training at the faculty on metaphors and their role in learning, cognition, etc. If they indicated that they had received it, their materials would be excluded from the analysis.

The quantitative scores provided by participants regarding their assessment of the appropriateness or inappropriateness of the gifts on the list were collected as measures. The scores were grouped into two categories or types, depending on the nature of each gift. Gifts could be cleaning or hygiene items (shower soap, toothpaste, window cleaner, disinfectant spray, and detergent) or other items (Post-it notes, juice, batteries, recording CD-ROMs, and candy bars). Within each category, the scores were totaled for each participant. This resulted in two scores for each participant: one for the total or sum of the appropriateness of the five gifts that were cleaning or hygiene products, and another for the total or sum of the five gifts in the “other” category. For each gift category, the average of the scores for each experimental condition was calculated. To determine whether there were differences between the aid experimental condition and the exploitative experimental condition when choosing these types of gifts, Student’s t-test was performed for equality of means.

3. Results

None of the participants reported receiving explicit training about metaphor and its potential role in education or cognition, so no response protocols related to this aspect were eliminated from the analysis.

Table 1 presents the results of the statistical analyses.

For each gift category, the average of the scores for each experimental condition was calculated, yielding the following four mean scores:

Regarding the rating of potential cleaning-related gifts, the mean rating was 10.52 points in the help condition out of a total of 35 possible points (30.06%), and the mean rating was 13.86 points in the exploitative condition out of a total of 35 possible points (39.6%). Regarding the rating of potential gifts unrelated to cleaning, in the “other” category, the mean rating was 19.86 points in the help condition out of a total of 35 possible points (56.74%), and the mean rating was 20.29 points in the exploitative condition out of a total of 35 possible points (57.97%).

To determine whether or not the variances could be assumed to be equal, Levene’s test for equality of variances was performed. For the scores on cleaning and hygiene-related gifts, the variances could be assumed to be equal (F = 0.56; p = 0.46). For the scores related to the other gift category, the variances could also be assumed to be equal (F = 0.03; p = 0.86). Thus, to determine whether there were differences between the aid experimental condition and the exploitative experimental condition when choosing these types of gifts, Student’s t-test was performed for equality of means, assuming equal variance. Significant differences were found in that, in the exploitative condition, more cleaning-related gifts were chosen than in the help experimental condition (t = −2.37; p < 0.05). The effect size was calculated using Cohen’s d index and a medium or moderate value was obtained (d = 0.66). To determine whether there were differences in the decision to give these types of gifts regarding the category of other gifts between the help experimental condition and the exploitative experimental condition, Student’s t-test was also performed to determine equality of means, assuming equal variance. The results showed no differences between the help experimental condition and the exploitative experimental condition (t = −0.38; p = 0.71). The effect size, also calculated using Cohen’s d index, yielded a value of (d = 0.10). That is, participants chose gifts unrelated to cleaning equally in both the help experimental condition and the exploitative experimental condition.

4. Discussion

In light of the results of this study, participants rated gifts related to cleanliness and personal hygiene as more desirable when the recipients had committed morally reprehensible acts than when those behaviors were helpful. However, when it came to gifts unrelated to cleanliness, there were no differences in the degree of desirability or appropriateness estimated by participants for the hypothetical gifts when comparing the potential recipients of those gifts (those who helped versus those who took advantage). This was even taking into account that participants were informed that all gifts had a similar financial cost. Therefore, the results suggest that gifts related to cleanliness or personal hygiene are considered more appropriate for people whose behavior is morally reprehensible than for people whose behavior is desirable or prosocial. This suggests that the McBeth effect extends to other people and not just to oneself when one feels bad about having personally committed a socially unjust act. In other words, we metaphorize moral indignation in terms of disgust not only when it relates to our own behavior, but also when it relates to the behavior of others. However, due to the small sample size and the fact that it is not representative of the population, as it was limited to education students at a public university in Madrid, the results, conclusions, and educational implications should be interpreted with caution.

Although the present study, unlike others, analyzes evaluations of the appropriateness or desirability of gifts when said evaluation relates to more or less morally desirable behaviors that concern other people and not oneself, these results point in line with the findings of

Zhong and Liljenquist (

2006). As indicated above, these authors asked their participants to copy a comic strip. This comic strip could depict morally desirable or undesirable behavior. They found that when participants had to copy the comic strip that described the most immoral behavior, they rated the cleaning products as more desirable. In the present study, rather than judging the greater or lesser desirability of the cleaning products as a personal assessment, participants were asked to assess said desirability or appropriateness by projecting it onto another person, the person who was engaging in said moral or immoral behavior. That is, there was an assessment of the appropriateness of the gift in relation to the behavior of another person, not one’s own. However, the results point in the same direction: we rate cleaning products as more appropriate when dealing with morally reprehensible behavior. The results of the present study also fit with those of

Chapman et al. (

2009). Recall that these authors found that when faced with an unfair distribution of coins, participants more often displayed facial expressions of disgust.

Since this study found a projection of this socio-moral metaphor onto the other person, which allows us to understand guilt or moral transgression in terms of filth, this finding constitutes a bridge between empathy, moral judgment, and the understanding of emotions, allowing for a connection between social agents when it comes to understanding how the other person might feel after committing a socially reprehensible act. Thus, in line with the original proposal by Salovey and Mayer (

Mayer et al., 2016;

Mayer & Salovey, 1997), emotional understanding represents one of the four dimensions of emotional intelligence. This emotional competence enables students to empathize with others (

OECD, 2021). Therefore, the socio-emotional metaphor that links moral indignation and feelings of guilt with filth contributes, as reflected in the results of this study, to putting others in their place when they commit a moral transgression. Thus, this constitutes a way of promoting that connection and understanding of others’ emotions can be useful when working on empathy and, ultimately, in creating an inclusive climate in the classroom, given that empathy is related to higher levels of social responsibility, emotional effectiveness, and prosocial behavior (

Silke et al., 2024). In any case, it is worth continuing to investigate this educational use of metaphor, extending it to other contexts and other possible variables.

In this sense, the analyzed metaphor emerges as a possible educational strategy, both for promoting emotional competence and for promoting inclusive education. On the one hand, it is important to keep in mind that emotional intervention programs provide advantages, including, for example, reducing conflicts in the classroom or promoting cognitive development and academic performance (

Araque, 2017). On the other hand, it is important to consider that the metaphor itself is a resource that should be incorporated into the classroom, as indicated by some studies (

Andrada & Civarolo, 2020;

Molina Rodelo, 2021). Furthermore, in relation to inclusive education, the metaphor is also associated with an inclusive classroom climate (

Herranz-Hernández et al., 2024;

Newland et al., 2019) and with the teaching of inclusive thinking (

Herranz-Hernández & Naranjo-Crespo, 2023). Therefore, the educational use of this metaphor could contribute to creating more inclusive classrooms and educational environments, while also fostering the development of cognitive and socioemotional skills in students, as well as in future teachers. This is reinforced by the fact that this study involved students from the Faculty of Education and that there is evidence that training in socio-emotional and relational skills, not only for students but also for teachers, has a positive impact on children’s development (

Hatzichristou & Lianos, 2016). This is in line with the recommendations from the study by

Symeonidou (

2017), which highlights the need to promote skills in teachers that allow them to detect and minimize the barriers that hinder the participation of all students. In this sense, it is worth noting that inclusive attitudes of teachers are related to student cohesion and satisfaction in the classroom, which is linked to inclusion (

Weber & Greiner, 2019). It is also worth noting that the results of this study point in a similar direction to those of

Crispel and Kasperski (

2021), who found that when teachers were trained in skills such as empathy, acceptance of others, and sensitivity, teachers displayed more supportive, understanding, and tolerant attitudes towards their students, especially those with disabilities. They also showed that empathy favored the creation of school environments in which students feel respected and understood, which increased their level of participation, a key aspect of inclusion, which must go beyond mere presence.

Cefai et al. (

2018) also point out that, with regard to teachers, adequate teacher training impacts quality when implementing emotional education programs.

Since educational institutions must strive for inclusive education (

Slee & Tait, 2022), any effort aimed at this goal is justified. Teachers, therefore, must possess not only cognitive skills, but also socio-emotional ones. The latter enable the creation of a positive classroom climate conducive to inclusion and fostering empathy (

Crisol-Moya et al., 2023). In this sense, the results of this study point to the usefulness of using the metaphor of moral indignation or guilt in terms of filth to encourage putting others in their shoes when they have transgressed the norm. This can be a way of developing empathy, as well as even teaching forgiveness. Forgiveness, thus considered, is a way of promoting inclusion. When someone does not forgive us, they are, in a way, excluding us, at least from their lives. Therefore, the use of this type of metaphor could be useful in the classroom, both for preservice teachers and for the students they are ultimately intended for, who are often younger. For example, potential uses could include the following: explicit instruction on metaphors and embodied metaphors; cooperative group discussions in which, for example, metaphors are generated to refer to situations of exclusion and inclusion, emotions, etc.; and including the use of metaphors related to emotions and inclusive education in the curriculum. This will be beneficial for both preservice teachers and students.

On the other hand, if we take into account that Universal Design for Learning (UDL) considers, in its basic principles, that different forms of representation must be promoted and that multiple forms of action and expression must be promoted (

CAST, n.d.), by using this metaphor, the aspects included in both principles are being worked on and the probability of this specific aspect of emotional education being accessible to more students is increased. This is mainly because, through metaphor, by enabling access to the complex or unknown in terms of the known and accessible, we foster access to complex concepts, such as, in this case, emotional concepts. Likewise, by helping students to understand emotions, we, in turn, foster an inclusive emotional climate in the classroom. The use of metaphor, in this case, while fostering an inclusive objective by placing others in their place to improve socio-emotional and inclusive competence, is also carried out in an accessible and, therefore, inclusive way. That is, both the objective and the means of achieving it would be inclusive, representing a way of leading by example when it comes to inclusion. Furthermore, this duality or splitting could also be applied both to teaching students and to teacher training, since, ultimately, an inclusive classroom requires positive attitudes favorable to diversity on the part of all stakeholders, including students and teachers. Therefore, given the rootedness of metaphor in human cognition, metaphor as a resource can be used in the training of both parties in inclusive education.

However, some limitations of this study should be noted. On the one hand, given the limited scope of the metaphor, it is worth considering, in line with the systematic review carried out on the didactic use of analogy and metaphor by

Portela et al. (

2022), whether students are aware of these limits and, if not, to make them aware. In this sense, it may be useful to discuss these limits of the metaphor in class groups. Another limitation is given by the age characteristics of the sample taken for this study. These were university students, so it could be interesting to study, from an evolutionary perspective, how this metaphor is developed or constructed in childhood, as, for example, is carried out in the study on the development of the metaphor that conceives inclusion as warmth and exclusion as cold (

Herranz-Hernández & Naranjo-Crespo, 2023). Other limitations arise from the sample size of this study. On the one hand, it is small. On the other, it is limited to students from a Faculty of Education in Madrid. It is also worth considering the prevalence of female students compared to male students at this faculty, which made it difficult to recruit a larger number of male students for the present study. The scope of the metaphor derived from the results of this study is only relative, and the degree of generalization of the applicability of this type of metaphor is also limited. This is especially true given that it constitutes only one type of embodied metaphor related to socio-emotional aspects; others could be explored.

Future research could explore these avenues in order to determine when to begin working with the metaphor of moral indignation or guilt as dirt or disgust in the classroom. Furthermore, future research could aim to replicate these results with other populations, for example, younger and more diverse ones, in order to make the results more generalizable.