Understanding the Relationship Between Educational Leadership Preparation Program Features and Graduates’ Career Intentions

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To what extent are key ELPP features directly associated with graduates’ career intentions to become school leaders?

- To what extent do some of the ELPP features indirectly influence graduates’ career intentions through other ELPP features?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Theoretical Foundation: Social Cognitive Career Theory

2.2. ELPP Features and Graduate Outcomes

2.3. ELPP Features and Graduate Career Outcomes

2.4. The Mediating Effects of Specific ELPP Features

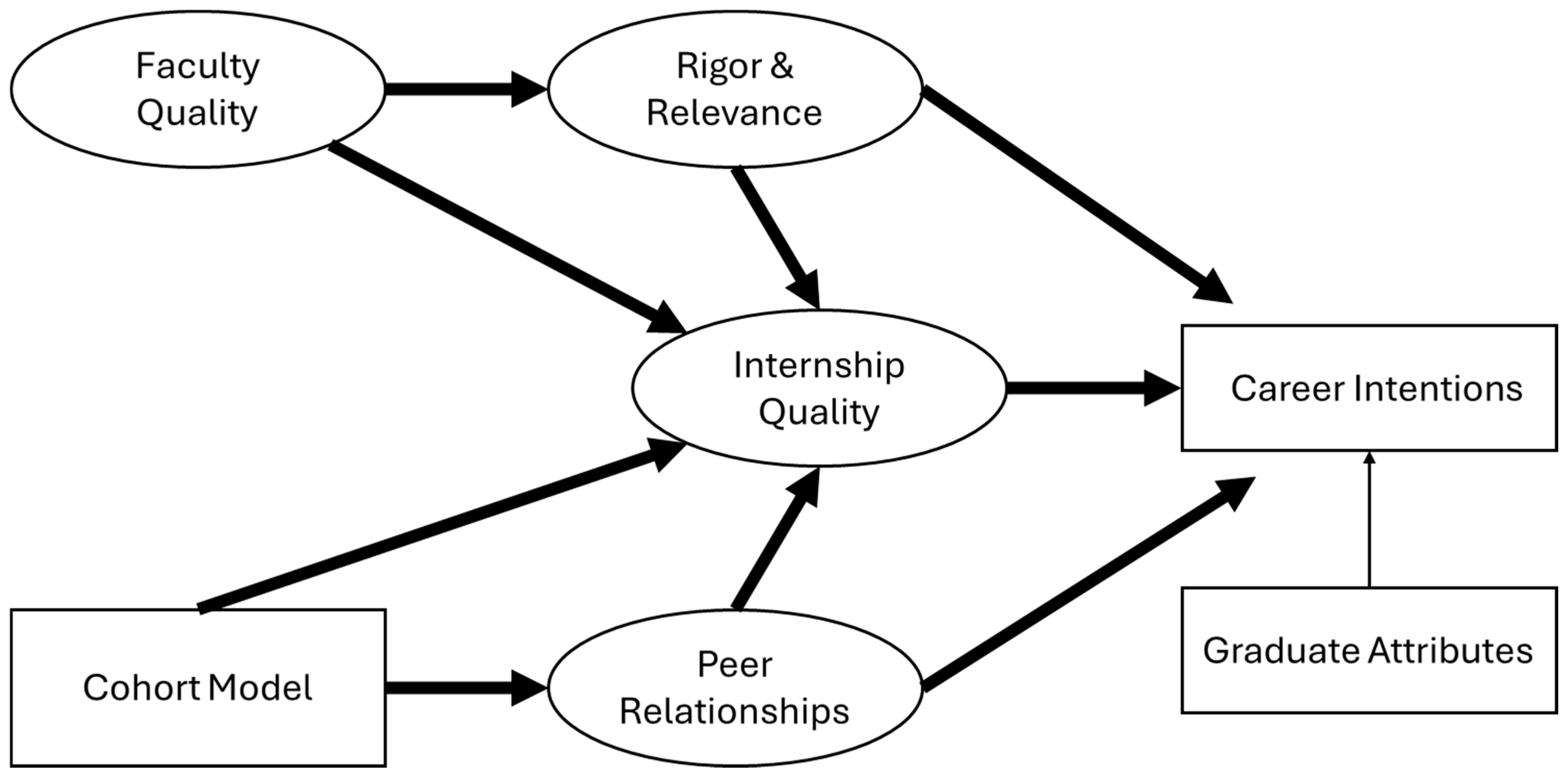

2.5. Conceptual Framework

3. Methods

3.1. Data Source and Sample

3.2. Variables and Constructs

- Faculty quality: “The faculty/instructors were knowledgeable”.

- Program rigor and relevance: “The program integrated theory and practice”.

- Internship quality: “My Internship enabled me to develop the practice of engaging peers and colleagues in shared problem solving and collaboration”.

- Peer relationships: “My interactions with fellow students have had a positive influence on my professional growth”.

3.3. Analysis Procedure

4. Results

4.1. Results of Measurement Models

4.2. Results of Correlation Analysis

4.3. Evaluation of SEM Models

4.4. Results of SEM Analysis

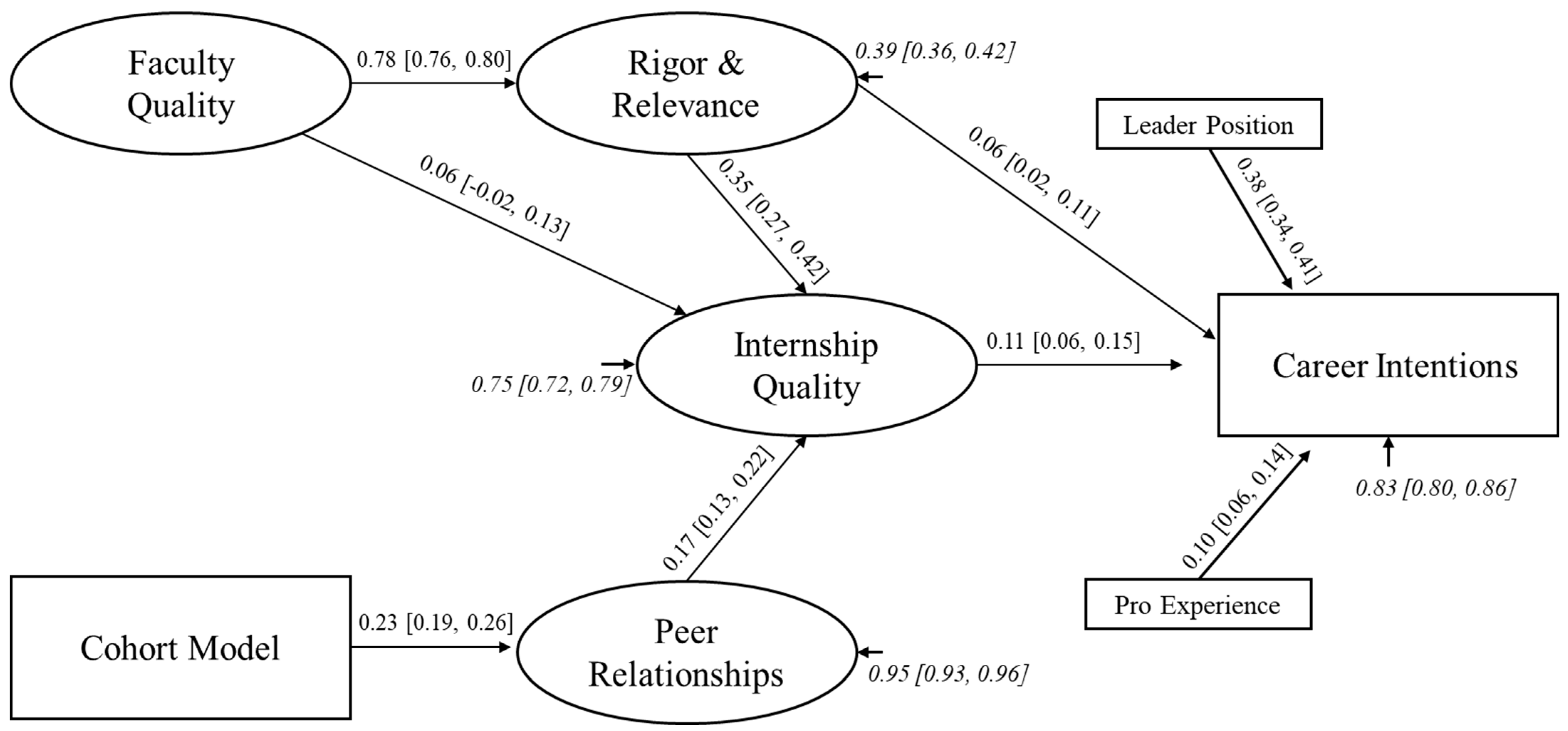

4.4.1. Faculty Quality

4.4.2. Program Rigor and Relevance

4.4.3. Cohort Model

4.4.4. Peer Relationships

4.4.5. Internship Quality

4.4.6. Control Variables

4.5. Models’ Explanatory Power–Variance Explained

5. Discussions and Conclusions

5.1. Key Findings

5.2. Connection with Existing Literature and Theory

5.3. Implications for Practice and Policy

5.4. Limitations and Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aldridge, J. M., & McLure, F. I. (2024). Preparing schools for educational change: Barriers and supports-a systematic literature review. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 23(3), 486–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barakat, M., Reames, E., & Kensler, L. A. (2019). Leadership preparation programs: Preparing culturally competent educational leaders. Journal of Research on Leadership Education, 14(3), 212–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borden, A. M., Preskill, S. L., & DeMoss, K. (2012). A new turn toward learning for leadership: Findings from an exploratory coursework pilot project. Journal of Research on Leadership Education, 7(1), 123–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne-Ferrigno, T., & Muth, R. (2009). Candidates in educational leadership graduate programs. In M. D. Young, G. M. Crow, J. Murphy, & R. T. Ogawa (Eds.), Handbook of research on the education of school leaders (pp. 195–224). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, C. (2012). From partnership formation to collaboration: Developing a state mandated university-multidistrict partnership to design a PK–12 principal preparation program in a rural service area. Planning and Changing, 43(3/4), 363–375. [Google Scholar]

- Coelli, M., & Green, D. A. (2012). Leadership effects: School principals and student outcomes. Economics of Education Review, 31(1), 92–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosner, S., Tozer, S., Zavitkovsky, P., & Whalen, S. (2015). Cultivating exemplary school leadership at a research intensive university. Journal of Research on Leadership Education, 10(1), 11–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crow, G. M., & Whiteman, R. (2016). Effective preparation program features: A literature review. Journal of Research on Leadership Education, 11(1), 120–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling-Hammond, L., Meyerson, D., La Pointe, M. M., & Orr, M. T. (2009). Preparing principals for a changing world. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Darling-Hammond, L., Wechsler, M. E., Levin, S., & Tozer, S. (2022). Developing effective principals: What kind of learning matters? Learning Policy Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, S., & Darling-Hammond, L. (2012). Innovative principal preparation programs: What works and how we know. Planning and Changing, 43(1–2), 25–45. [Google Scholar]

- Donmoyer, R., Yennie-Donmoyer, J., & Galloway, F. (2012). The search for connections across principal preparation, principal performance, and student achievement in an exemplary principal preparation program. Journal of Research on Leadership Education, 7(1), 5–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, T. A., & Bastian, K. C. (2024). The geography of principal Internships in North Carolina. AERA Open, 10, 23328584231219994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, E., Reynolds, A., & O’Doherty, A. (2017). Recruitment, selection, and placement of educational leadership students. In M. Young, & G. Crow (Eds.), Handbook of research on the education of school leaders (pp. 77–117). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller, E. J., Hollingworth, L., & An, B. P. (2016). The impact of personal and program characteristics on the placement of school leadership preparation graduates in school leadership positions. Educational Administration Quarterly, 52(4), 643–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenlee, B. J., & Karanxha, Z. (2010). A study of group dynamics in educational leadership cohort and non-cohort groups. Journal of Research on Leadership Education, 5(11), 357–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grissom, J. A., Egalite, A. J., & Lindsay, C. A. (2021). How principals affect students and schools. A systematic synthesis of two decades of research. The Wallace Foundation. Available online: http://www.wallacefoundation.org/principalsynthesis (accessed on 14 February 2025).

- Grissom, J. A., Mitani, H., & Woo, D. (2019). Principal preparation programs and principal outcomes. Educational Administration Quarterly, 55(1), 73–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Black, W. C. (2018). Multivariate data analysis (8th ed.). CENGAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Hitt, D. H., & Tucker, P. D. (2016). Systematic review of key leader practices found to influence student achievement: A unified framework. Review of Educational Research, 86(2), 531–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, S., McCarthy, M., & Pounder, D. (2015). What makes a leadership preparation program exemplary? Journal of Research on Leadership Education, 10(1), 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakose, T., Leithwood, K., & Tülübaş, T. (2024). The intellectual evolution of educational leadership research: A combined bibliometric and thematic analysis using SciMAT. Education Sciences, 14(4), 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. (2005). Methodology in the social sciences: Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- LaFrance, J., & Beck, D. (2014). Mapping the terrain: Educational leadership field experiences in K-12 virtual schools. Educational Administration Quarterly, 50(1), 160–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithwood, K., Harris, A., & Hopkins, D. (2020). Seven strong claims about successful school leadership revisited. School Leadership & Management, 40(1), 5–22. [Google Scholar]

- Leithwood, K., Louis, K., Anderson, S., & Wahlstrom, K. (2004). How leadership influences student learning. The Wallace Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Hackett, G. (1994). Toward a unifying social cognitive theory of career and academic interest, choice, and performance. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 45(1), 79–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, A. (2005). Educating school leaders. (Policy Report No. 1). The Education Schools Project. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, M. (2015). Reflections on the evolution of educational leadership preparation programs in the United States and challenges ahead. Journal of Educational Administration, 53(3), 416–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Y., Hollingworth, L., Rorrer, A., & Pounder, D. (2017). The evaluation of educational leadership preparation programs. In M. Young, & G. Crow (Eds.), Handbook of research on the education of school leaders (2nd ed., pp. 285–307). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ni, Y., Rorrer, A. K., Pounder, D., Young, M., & Korach, S. (2019). Leadership matters: Preparation program quality and learning outcomes. Journal of Educational Administration, 57(2), 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Y., Rorrer, A. K., Xia, J., Pounder, D., & Young, M. (2023). Educational leadership preparation program features and graduates’ assessment of program quality. Journal of Research on Leadership Education, 18(3), 457–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, M. T. (2011). Pipeline to preparation to advancement: Graduates’ experiences in, through, and beyond leadership preparation. Educational Administration Quarterly, 47(1), 114–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, M. T. (2023). Reflections on leadership preparation research and current directions. Frontiers in Education, 8, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, M. T., & Barber, M. E. (2007). Collaborative leadership preparation: A comparative study of innovative programs and practices. Journal of School Leadership, 16, 709–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, M. T., & Orphanos, S. (2011). How graduate-level preparation influences the effectiveness of school leaders: A comparison of the outcomes of exemplary and conventional leadership preparation programs for principals. Educational Administration Quarterly, 47(1), 18–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, L., Uline, C., Johnson, F., James-Ward, C., & Basom, M. (2011). Foregrounding fieldwork in leadership preparation: The transformative capacity of authentic inquiry. Educational Administration Quarterly, 47(1), 217–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrone, F., Young, M. D., & Fuller, E. J. (2022). A call for data on the principal pipeline. Educational Researcher, 51(6), 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes, J., Rhone, R., Brock, J., & Bunch, P. (2025). An investigation of educational leaders’ cultural intelligence to influence supervision leadership: Perceptions of Ed.D. students. Journal of Educational Supervision, 8(1), 63–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Guerra, D., & Barnett, B. (2017). Clinical practice in educational leadership. In M. Young, & G. Crow (Eds.), Handbook of research on the education of school leaders (pp. 229–261). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Sahlin, S. (2025). Professional development of school principals-how do experienced school leaders make sense of their professional learning? Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 53(2), 380–397. [Google Scholar]

- Salazar, M., Pazey, B., & Zembik, M. (2013). What we’ve learned and how we’ve used it: Learning experiences from the cohort of a high-quality principalship program. Journal of Research on Leadership Education, 8(3), 304–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Wallace Foundation. (2016). Improving university principal preparation programs: Five themes from the field. The Wallace Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Tingle, E., Corrales, A., & Peters, M. L. (2019). Leadership development programs: Investing in school principals. Educational Studies, 45(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Winn, K. M., Anderson, E., Groth, C., Korach, S., Pounder, D., Rorrer, A., & Young, M. D. (2016). A deeper look: INSPIRE data demonstrates quality in educational leadership preparation. UCEA. [Google Scholar]

- Yeagley, E. E., Subich, L. M., & Tokar, D. M. (2010). Modeling college women’s perceptions of elite leadership positions with Social Cognitive Career Theory. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 77(1), 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ylimaki, R. M., & Henderson, J. G. (2016). Reconceptualizing curriculum in leadership preparation. In M. Young, & G. Crow (Eds.), Handbook of research on the education of school leaders (pp. 148–172). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Young, M. D., & Crow, G. M. (Eds.). (2017). Handbook of research on the education of school leaders: Historical, political, economic, and global influences. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

| 2015–2016 | 2016–2017 | 2017–2018 | 2018–2019 | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 1110 | 834 | 736 | 314 | 2667 | |||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Gender | ||||||||||

| Female | 606 | 64.1 | 531 | 70.1 | 470 | 69.7 | 187 | 64.5 | 1794 | 67.3 |

| Male | 340 | 35.9 | 226 | 29.9 | 204 | 30.3 | 103 | 35.5 | 873 | 32.7 |

| Race | ||||||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 742 | 66.8 | 548 | 65.7 | 494 | 67.1 | 233 | 74.2 | 2022 | 76.1 |

| Other | 201 | 21.3 | 204 | 27.1 | 174 | 25.9 | 57 | 19.7 | 636 | 23.9 |

| Teacher Leader Position | ||||||||||

| teacher or other | 298 | 30.5 | 131 | 17.2 | 115 | 16.9 | 44 | 21.7 | 588 | 21.7 |

| teacher leader | 300 | 30.7 | 370 | 48.5 | 399 | 58.7 | 198 | 46.8 | 1267 | 46.8 |

| assistant principal | 378 | 38.7 | 262 | 34.3 | 166 | 24.4 | 49 | 31.5 | 855 | 31.5 |

| M | STD | M | STD | M | STD | M | STD | M | STD | |

| Total professional experience (years) | 13.88 | 6.34 | 12.45 | 6.32 | 12.43 | 6.68 | 12.10 | 6.09 | 12.90 | 6.44 |

| Program Feature | Indicator | N | Mean | ST.D. | Factor Loading | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 95% CI | |||||

| Faculty Quality (FQ) | FQ1 | 2624 | 4.59 | 0.621 | 0.86 | [0.84, 0.88] |

| FQ2 | 2622 | 4.53 | 0.665 | 0.88 | [0.86, 0.89] | |

| FQ3 | 2623 | 4.49 | 0.723 | 0.81 | [0.79, 0.83] | |

| FQ4 | 2623 | 4.58 | 0.689 | 0.74 | [0.72, 0.76] | |

| Rigor and Relevance (RR) | RR1 | 2626 | 4.39 | 0.805 | 0.85 | [0.83, 0.86] |

| RR2 | 2626 | 4.45 | 0.796 | 0.86 | [0.85, 0.88] | |

| RR3 | 2624 | 4.56 | 0.709 | 0.78 | [0.76, 0.79] | |

| RR4 | 2621 | 4.47 | 0.739 | 0.81 | [0.79, 0.83] | |

| RR5 | 2623 | 4.43 | 0.823 | 0.85 | [0.83, 0.86] | |

| Internship Quality (Intern) | Intern1 | 2273 | 4.22 | 0.902 | 0.88 | [0.87, 0.89] |

| Intern2 | 2270 | 4.31 | 0.796 | 0.85 | [0.84, 0.86] | |

| Intern3 | 2270 | 4.21 | 0.885 | 0.86 | [0.85, 0.87] | |

| Intern4 | 2270 | 4.13 | 0.973 | 0.8 | [0.78, 0.82] | |

| Intern5 | 2268 | 4.38 | 0.84 | 0.71 | [0.69, 0.74] | |

| Intern6 | 2266 | 4.12 | 0.959 | 0.66 | [0.63, 0.68] | |

| Peer Relationships (PR) | PR1 | 2615 | 4.39 | 0.829 | 0.91 | [0.9, 0.92] |

| PR2 | 2617 | 4.4 | 0.821 | 0.91 | [0.9, 0.92] | |

| PR3 | 2617 | 4.1 | 1.094 | 0.78 | [0.76, 0.8] | |

| Cohort Model | 2564 | 0.73 | 0.443 | |||

| Career Intention | 2642 | 4.18 | 0.925 | |||

| Chi-Square | df | RMSEA 90% CI | SRMR | TLI | CFI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Faculty Quality | 15.240 | 1 | 0.073 [0.044, 0.108] | 0.007 | 0.973 | 0.995 |

| Rigor and Relevance | 53.349 | 5 | 0.061 [0.046, 0.076] | 0.016 | 0.988 | 0.976 |

| Internship Quality | 96.620 | 9 | 0.064 [0.052, 0.076] | 0.020 | 0.962 | 0.977 |

| FQ | RR | COH | PR | Intern | White | Female | ProExp | Leader | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | 0.75 | ||||||||

| [0.71, 0.80] | |||||||||

| COH | 0.01 | 0.09 | |||||||

| [−0.03, 0.06] | [0.05, 0.13] | ||||||||

| PR | 0.42 | 0.49 | 0.26 | ||||||

| [0.37, 0.47] | [0.44, 0.54] | [0.21, 0.30] | |||||||

| Intern | 0.4 | 0.48 | 0.05 | 0.37 | |||||

| [0.34, 0.45] | [0.42, 0.53] | [0.00, 0.09] | [0.32, 0.42] | ||||||

| Intention | 0.08 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.04 | −0.03 | 0.10 | 0.38 |

| [0.04, 0.12] | [0.07, 0.15] | [0.03, 0.10] | [0.05, 0.13] | [0.09, 0.18] | [0.00, 0.07] | [−0.07, 0.00] | [0.06, 0.14] | [0.35, 0.42] |

| Model | Chi-Square (χ2) | df | p | AIC | BIC | RMSEA | CFI | TLI | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1553.030 | 160 | 0.000 | 81,015.181 | 81,413.253 | 0.058 [0.056, 0.061] | 0.958 | 0.950 | 0.127 |

| 2 | 1719.250 | 232 | 0.000 | 79,539.006 | 79,959.706 | 0.050 [0.048, 0.052] | 0.955 | 0.949 | 0.107 |

| 3 | 1147.928 | 232 | 0.000 | 78,967.683 | 79,388.384 | 0.039 [0.037, 0.042] | 0.973 | 0.969 | 0.033 |

| Predictor | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI | β | 95% CI | p | |

| Direct Effects on Rigor & Relevance | |||||||

| Faculty Quality | 0.78 | [0.76, 0.80] | 0.78 | [0.76, 0.80] | 0.78 | [0.76, 0.8] | 0.00 |

| Direct Effects on Peer Relationship | |||||||

| Cohort Model | 0.26 | [0.22, 0.30] | 0.26 | [0.22, 0.30] | 0.23 | [0.19, 0.26] | 0.00 |

| Direct Effects on Internship Quality | |||||||

| Faculty Quality | 0.06 | [−0.02, 0.14] | 0.06 | [−0.02, 0.14] | 0.06 | [−0.02, 0.13] | 0.14 |

| Rigor and Relevance | 0.36 | [0.28, 0.44] | 0.36 | [0.28, 0.44] | 0.35 | [0.27, 0.42] | 0.00 |

| Peer Relationships | 0.20 | [0.15, 0.25] | 0.20 | [0.15, 0.25] | 0.17 | [0.13, 0.22] | 0.00 |

| Cohort Model | −0.03 | [−0.07, 0.01] | −0.02 | [−0.07, 0.02] | path removed | ||

| Direct Effects on Career Intention | |||||||

| Rigor and Relevance | 0.05 | [0.00, 0.10] | 0.05 | [0.01, 0.10] | 0.06 | [0.02, 0.11] | 0.01 |

| Peer Relationships | 0.02 | [−0.03, 0.07] | 0.03 | [−0.02, 0.07] | Path removed | ||

| Internship Quality | 0.13 | [0.08, 0.19] | 0.10 | [0.05, 0.14] | 0.11 | [0.06, 0.15] | 0.00 |

| Race (White vs. Other) | 0.03 | [0.00, 0.07] | 0.03 | [0.00, 0.07] | 0.07 | ||

| Gender (Female vs. Male) | −0.04 | [−0.07, 0.00] | −0.03 | [−0.07, 0.00] | 0.06 | ||

| Experience | 0.10 | [0.07, 0.14] | 0.10 | [0.06, 0.14] | 0.00 | ||

| Leader position | 0.38 | [0.34, 0.41] | 0.38 | [0.34, 0.41] | 0.00 | ||

| R-Square | |||||||

| Dependent variable | R2 | 95% CI | R2 | 95% CI | R2 | 95% CI | p |

| Career Intention | 0.03 | [0.01, 0.04] | 0.17 | [0.14, 0.19] | 0.17 | [0.14, 0.20] | 0.00 |

| Rigor and Relevance | 0.61 | [0.58, 0.64] | 0.61 | [0.58, 0.64] | 0.61 | [0.58, 0.64] | 0.00 |

| Internship Quality | 0.20 | [0.17, 0.23] | 0.20 | [0.17, 0.23] | 0.25 | [0.21, 0.28] | 0.00 |

| Peer Relationships | 0.07 | [0.05, 0.09] | 0.07 | [0.05, 0.09] | 0.05 | [0.04, 0.07] | 0.00 |

| β | 95% CI * | SE * | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Effect of Faculty Quality (FQ) | ||||

| Faculty Quality → Rigor&Relevance → Intention | 0.05 | [0.01, 0.08] | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Faculty Quality → Internship → Intention | 0.01 | [−0.002, 0.01] | 0.00 | 0.16 |

| Faculty Quality → Rigor&Relevance → Internship → Intention | 0.03 | [0.01, 0.04] | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Total Indirect Effect of FQ | 0.08 | [0.05, 0.11] | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| Effect of Cohort | ||||

| Cohort model → Peer Relationships → Internship → Intention | 0.004 | [0.002, 0.01] | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Effect of Rigor & Relevance (RR) | ||||

| Rigor&Relevance → Internship → Intention | 0.04 | [0.02, 0.05] | 0.01 | 0.00 |

| Direct Rigor&Relevance → Intention | 0.06 | [0.02, 0.11] | 0.02 | 0.01 |

| Total Effect of RR | 0.10 | [0.06, 0.14] | 0.02 | 0.00 |

| Effect of Peer Relationships | ||||

| Peer Relationships → Internship → Intention | 0.02 | [0.01, 0.03] | 0.01 | 0.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xia, J.; Ni, Y.; Rorrer, A.K.; Xu, L.; Young, M.D. Understanding the Relationship Between Educational Leadership Preparation Program Features and Graduates’ Career Intentions. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 575. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050575

Xia J, Ni Y, Rorrer AK, Xu L, Young MD. Understanding the Relationship Between Educational Leadership Preparation Program Features and Graduates’ Career Intentions. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(5):575. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050575

Chicago/Turabian StyleXia, Jiangang, Yongmei Ni, Andrea K. Rorrer, Lu Xu, and Michelle D. Young. 2025. "Understanding the Relationship Between Educational Leadership Preparation Program Features and Graduates’ Career Intentions" Education Sciences 15, no. 5: 575. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050575

APA StyleXia, J., Ni, Y., Rorrer, A. K., Xu, L., & Young, M. D. (2025). Understanding the Relationship Between Educational Leadership Preparation Program Features and Graduates’ Career Intentions. Education Sciences, 15(5), 575. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050575