The Effect of Drama Education on Enhancing Critical Thinking Through Collaboration and Communication

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Drama Education and the 5Cs

1.2. Collaboration and Communication Play a Crucial Role

1.3. Objectives of the Study

- To explore the impacts of collaboration and communication on students’ critical thinking in drama education.

- To explore potential trends based on gender, with the acknowledgment that the gender imbalance in the sample limits the ability to draw statistically significant conclusions. The analysis focus on identifying observable patterns, rather than inferring causal relationships or generalizable findings.

- To investigate the role of drama performance and role-playing experiences in shaping students’ learning outcomes, particularly in fostering critical thinking.

1.4. Significance of the Study

2. The Role of Drama Education in Promoting the Core Literacies: 5Cs

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

3.2. Study Reliability, Validity and Ethical Considerations

3.3. Data Collection and Analysis Methods

4. Questionnaire Results and Discussion

4.1. Results

4.2. Regression Analysis of Collaboration, Communication and Critical Thinking in Drama Education

- 1.

- Main Effects

- 2.

- Interaction Effects

- 3.

- Conditional Effects

- 4.

- Synergistic Impact of Collaboration and Communication on Critical Thinking

- 5.

- Conclusions

5. Interview Results and Discussion

5.1. Results

- 1.

- Collaborative Engagement Expands Cognitive Perspectives

“Working with teammates helped me see the character from different angles”.(Participant D, female)

- 2.

- Dialogic Interaction Fosters Reflective Thinking

“Through rehearsing and discussing with others, I learned to express and refine my ideas”.(Participant K, female)

- 3.

- Synergistic Learning Through Integration

“By combining our efforts and discussing ideas, we found better ways to solve script issues”.(Participant E, female)

5.2. Interplay of Collaboration, Communication and Role Experience in Developing Critical Thinking and Core Literacies

5.2.1. How Collaboration and Communication Promote Critical Thinking

- 1.

- Teamwork as a Key Contributor to the Development of Critical Thinking

“I had to thoughtfully explain the character’s change in attitude. When naysayers couldn’t convince me, I had to reevaluate my logic”.

- 2.

- Communication as a Driver of Critical Thinking

“What makes the character quiet at this part of the script?”

These instances emphasize the importance of a reflective dialog (McNatt, 2019) and performance in building analytical (Rowland, 2002) and evaluative skills (Zhang et al., 2009).“How does this moment change the whole story?”

- 3.

- Synergistic Effects of Collaboration and Communication

- 4.

- Quantitative and Qualitative Validation

- 5.

- Conclusions

5.2.2. Gender Differences in Core Literacies

5.2.3. How Role Experience Impacts Students’ Backgrounds and Characteristics

6. Conclusions and Implications

7. Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Ahmad, S., Ch, A. H., Batool, A., Sittar, K., & Malik, M. (2016). Play and cognitive development: Formal operational perspective of piaget’s theory. Journal of Education and Practice, 7(28), 72–79. [Google Scholar]

- Alfonso-Benlliure, V., Teruel, T. M., & Fields, D. L. (2021). Is it true that young drama practitioners are more creative and have a higher emotional intelligence? Thinking Skills and Creativity, 39, 100788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M. (2013). The effect of the project method on the development of creative thinking, critical thinking and emotional intelligence: A case study of secondary school students in the State of Kuwait [Ph.D. dissertation, University of Zurich]. [Google Scholar]

- Angelianawati, L. (2019). Using drama in EFL classroom. Journal of English Teaching, 5(2), 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M. (2015). Collaboration in collaborative learning. Coordination, Collaboration and Cooperation, 16(3), 451–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, P., & Fleming, K. (2003). Teaching literacy through drama: Creative approaches. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Barigai, A., & Heravdakar, L. (2024). Exploring the dynamics of learning communities in fostering collaboration and knowledge exchange. Journal of Education Review Provision, 4(1), 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bear, J. B., & Woolley, A. W. (2011). The role of gender in team collaboration and performance. Interdisciplinary Science Reviews, 36(2), 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borromeo, V. (2020). Perceived influence of an acting class on students’ verbal communication skills [Ph.D. dissertation, Walden University]. [Google Scholar]

- Chinn, C. A., & Clark, D. B. (2013). Learning through collaborative argumentation. In The international handbook of collaborative learning (pp. 314–332). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W. (1999). Mixed-method research: Introduction and application. In Handbook of educational policy (pp. 455–472). Academic press. [Google Scholar]

- Çerkez, Y., Altinay, Z., Altinay, F., & Bashirova, E. (2012). Drama and role playing in teaching practice: The role of group works. Journal of Education and Learning, 1(2), 109–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, C. E. (2006). Transformative learning through critical reflection: The relationship to emotional competence. The George Washington University. [Google Scholar]

- Finnegan, R. (2014). Communicating. Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forman, E. A., & Cazden, C. B. (2013). Exploring Vygotskian perspectives in education: The cognitive value of peer interaction. In Learning relationships in the classroom (pp. 189–206). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ghavifekr, S. (2020). Collaborative learning: A key to enhance students’ social interaction skills. MOJES: Malaysian Online Journal of Educational Sciences, 8(4), 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ghiasi, G., Larivière, V., & Sugimoto, C. R. (2015). On the compliance of women engineers with a gendered scientific system. PLoS ONE, 10(12), e0145931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, E., & Elhawary, D. (2018). Exploring collaborative interaction and self-direction in teacher learning teams: Case-studies from a middle-income country analysed using vygotskian theory. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 50(1), 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, W. E., & Pinard, M. R. (2015). Critically examining inquiry-based learning: John dewey in theory, history, and practice. Innovations in Higher Education Teaching and Learning, 3, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, A. C. (2001). Supporting critical thinking with group discussion on threaded bulletin boards: An analysis of group interaction. The University of Wisconsin-Madison. [Google Scholar]

- Kao, S. M., & O’Neill, C. (1998). Words into worlds: Learning a second language through process drama. Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Khozin, K., Tobroni, T., & Rozza, D. S. (2024). Implementation of albert bandura’s social learning theory in student character development. International Journal of Advanced Multidisciplinary, 3(1), 102–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, E. (2011). Critical thinking: A literature review research report. Pearson. Available online: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=b42cffa5a2ad63a31fcf99869e7cb8ef72b44374 (accessed on 12 January 2024).

- Mahama, I. (2024). The role of culture and environment in shaping creative thinking. IntechOpen. Available online: https://www.intechopen.com/chapters/1202527 (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- McNatt, D. B. (2019). Enhancing public speaking confidence, skills, and performance: An experiment of service-learning. The International Journal of Management Education, 17(2), 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, B. T., Camarda, A., Mercier, M., Burkhardt, J.-M., Morisseau, T., Bourgeois-Bougrine, S., Vinchon, F., El Hayek, S., Augereau-Landais, M., Mourey, F., Feybesse, C., Sundquist, D., & Lubart, T. (2023). Creativity, critical thinking, communication, and collaboration: Assessment, certification, and promotion of 21st century skills for the future of work and education. Journal of Intelligence, 11(3), 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miri, B., David, B.-C., & Uri, Z. (2007). Purposely teaching for the promotion of higher-order thinking skills: A case of critical thinking. Research in Science Education, 37(4), 353–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortensen, C. D. (2017). Communication theory. Google Books. Available online: https://books.google.co.jp/books?hl=zh-CN&lr=&id=pNwzDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PT6&dq=communication+theory+emphasizes+the+process+of+transferring+information+between+individuals (accessed on 3 April 2024).

- Mumford, M. D., Zaccaro, S. J., Harding, F. D., Jacobs, T. O., & Fleishman, E. A. (2000). Leadership skills for a changing world: Solving complex social problems. The Leadership Quarterly, 11(1), 11–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munin, N., & Efron, Y. (2017). Role-playing brings theory to life in a multicultural learning environment. Journal of Legal Education, 66(2), 309–331. [Google Scholar]

- Naughton, D. (2006). Cooperative strategy training and oral interaction: Enhancing small group communication in the language classroom. The Modern Language Journal, 90(2), 169–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neelands, J. (2009). Acting together: Ensemble as a democratic process in art and life. RiDE: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance, 14(2), 173–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholson, H., & Bond, E. (2017). Theatre and education. Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Nikoi, E. (Ed.). (2013). Collaborative communication processes and decision making in organizations. IGI Global. [Google Scholar]

- Pathan, H., Memon, R. A., Memon, S., Khoso, A. R., & Bux, I. (2018). A critical review of vygotsky’s socio-cultural theory in second language acquisition. International Journal of English Linguistics, 8(4), 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proudfoot, D., Kay, A. C., & Koval, C. Z. (2015). A gender bias in the attribution of creativity. Psychological Science, 26(11), 1751–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowland, G. E. (2002). Every child needs self-esteem: Creative drama builds self-confidence through self-expression. The Union Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, H. (2025). Collaborative leadership. Google Books. Available online: https://books.google.co.jp/books?hl=zh-CN&lr=&id=8HDAuVJPcB8C&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=This+teamwork+experience+enhances+their+leadership (accessed on 16 September 2024).

- Stake, R. (1995). Case study research. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Starko, A. J. (2021). Creativity in the classroom: Schools of curious delight. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Storm, W. (2016). Dramaturgy and dramatic character. Google Books. Available online: https://books.google.com.hk/books?hl=zh-CN&lr=&id=XRp-CwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR9&dq=students+become+familiar+with+the+dramaturgy+concept+through+the+literature+of+plays (accessed on 17 August 2024).

- Syukri, M. Y., Widyasari, E., & Fuadi, D. (2024). Communication-based classrooms: A new approach to inclusive education. Indonesian Journal of Education (INJOE), 4(2), 568–581. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, V. D. (2013). Theoretical perspectives underlying the application of cooperative learning in classrooms. International Journal of Higher Education, 2(4), 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavrus, M. J. (2002). Transforming the multicultural education of teachers: Theory, research, and practice (Vol. 12). Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C., & Huang, L. (2021). A systematic review of serious games for collaborative learning: Theoretical framework, game mechanic and efficiency assessment. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning, 16(6), 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, R., Liu, J., Bai, X., Ma, X., Liu, Y., Ma, L., Gan, Q., Kang, C., & Xu, G. (2020). The research design of the 5cs framework for twenty-first century key competences. Journal of East China Normal University (Educational Sciences), 38(2), 20. [Google Scholar]

- West, T. (2021). Drama education: Towards building peer relationships between culturally diverse adolescents [Ph.D. dissertation, Murdoch University]. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L., Gillies, M., Dhaliwal, K., Gower, A., Robertson, D., & Crabtree, B. (2009). E-Drama: Facilitating online role-play using an AI actor and emotionally expressive characters. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 19(1), 5–38. [Google Scholar]

| b | se | t | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 0.170 | 1.989 | 0.086 | 0.932 |

| Communication | 0.127 | 0.125 | 1.011 | 0.315 |

| Collaboration | 0.436 | 0.105 | 4.143 | 0.000 |

| Communication x collaboration | 0.236 | 0.068 | 3.451 | 0.001 |

| Age | −0.004 | 0.096 | −0.044 | 0.965 |

| Gender | 0.087 | 0.278 | 0.314 | 0.755 |

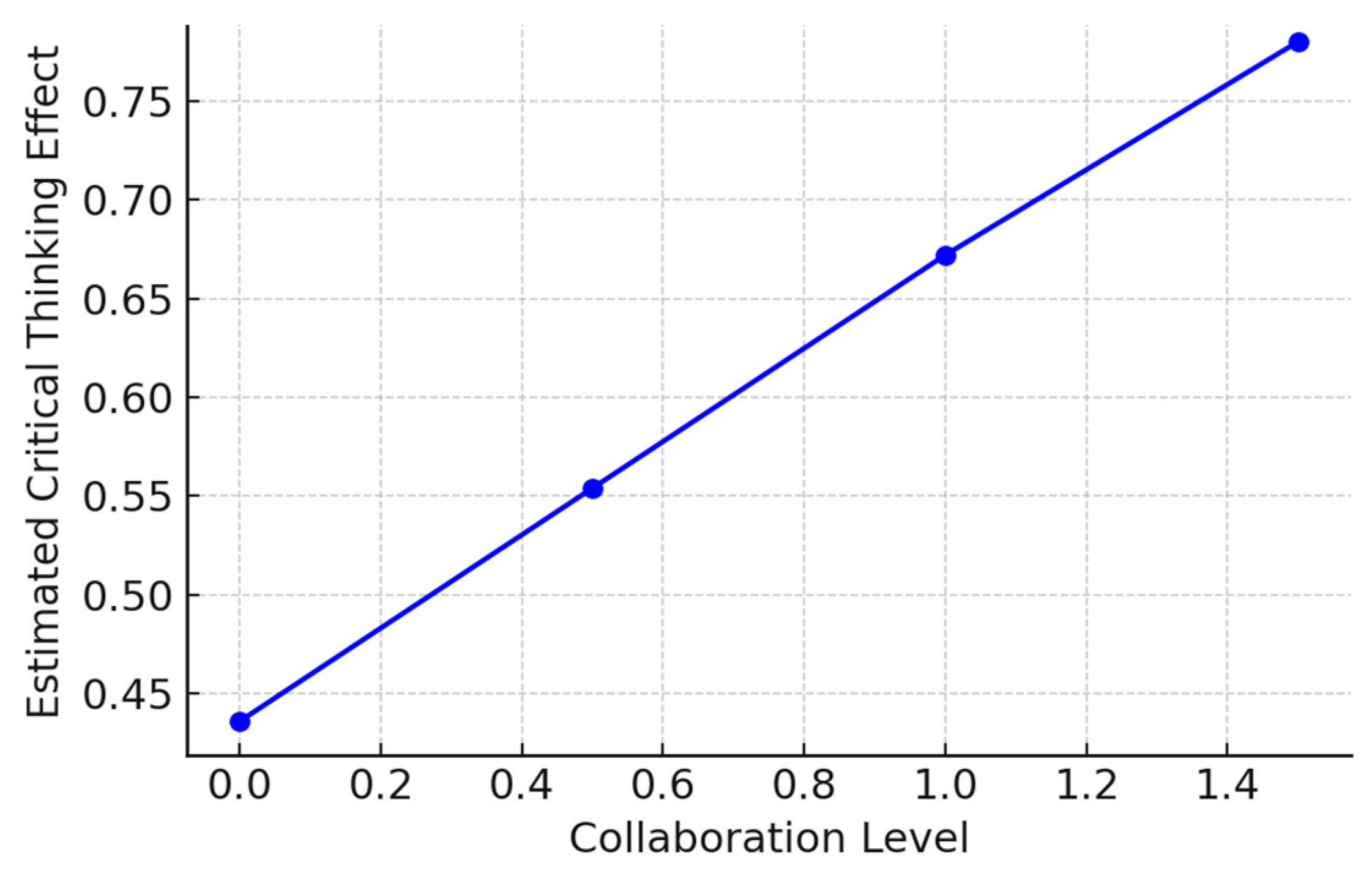

| Conditional effects | b | se | LLCI | ULCI |

| Collaboration | ||||

| 0.00 | 0.127 | 0.125 | −0.122 | 0.376 |

| 0.50 | 0.245 | 0.116 | 0.015 | 0.474 |

| 1.50 | 0.480 | 0.125 | 0.232 | 0.729 |

| Communication | ||||

| 0.00 | 0.436 | 0.105 | 0.227 | 0.645 |

| 0.50 | 0.554 | 0.106 | 0.342 | 0.765 |

| 1.00 | 0.672 | 0.118 | 0.437 | 0.906 |

| Theme | Example Quote | Role | Gender | Observed Behavior Supporting Claim |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collaboration and Perspective Taking | “Helped me evaluate from multiple views.” | Director | Female | Initiated alternative character readings and revised narrative to integrate peer input |

| Communication and Reflection | “Rehearsing with peers improved my clarity.” | Actress | Female | Shifted from vague to specific expressions after peer dialog during rehearsal |

| Synergistic Learning | “We co-created and refined ideas.” | Scriptwriter | Male | Jointly revised scenes through dialog, gestures and feedback during ensemble rehearsal |

| Student | Gender | Job | Experience and Feelings |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | M | Main actor | Emotional expression, character empathy. |

| B | F | PPT producer | Effective communication. Working closely with teammates allowed me to critically analyze how to best present ideas visually. |

| C | F | Main actress | Body language, facial expressions and voice convey emotions. Through team discussions, I refined my understanding of the script critically. |

| D | F | Scriptwriter | Co-creation of scenarios. Collaboration with the team helped me evaluate and improve the storyline effectively. |

| E | F | Director | Coordinated division of labor and joint problem solving. By leading group discussions, I critically evaluated others’ ideas and proposed solutions. |

| F | M | Director | Unique understanding of characters and plots. Collaboration enabled me to view the story from multiple perspectives, sharpening my critical thinking. |

| G | F | Voice actor | Adding creative elements for individualized performances. |

| H | F | Main actress | Teaching drama offers a significant cognitive expansion in creative problem-solving. |

| I | F | Assistant director | Creativity develops through metacognitive engagement, experimenting and using your imagination. |

| J | F | Main actress | Self-confidence develops with continued practice and performance. |

| K | F | PPT producer | Identify and evaluate information, dare to express and present your views. |

| L | F | Supporting actress | Understand characters and think deeply about their motivations, emotional changes. Group collaboration helped me refine my interpretation of these emotions critically. |

| M | F | Supporting actress | The increased depth of thought prompted me to focus on the details of the characters. Team discussions allowed me to explore the nuances of the characters’ actions critically. |

| N | F | Prop maker | In character analysis and script reading, I learned how to ask insightful questions. Collaborative script reading enhanced my critical thinking about character development. |

| O | F | Choreographer | Think about character behavior and plot development from multiple perspectives. Communicating with performers deepened my ability to critically evaluate choreography choices. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hu, Y.; Shu, J. The Effect of Drama Education on Enhancing Critical Thinking Through Collaboration and Communication. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 565. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050565

Hu Y, Shu J. The Effect of Drama Education on Enhancing Critical Thinking Through Collaboration and Communication. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(5):565. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050565

Chicago/Turabian StyleHu, Yaxin, and Jack Shu. 2025. "The Effect of Drama Education on Enhancing Critical Thinking Through Collaboration and Communication" Education Sciences 15, no. 5: 565. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050565

APA StyleHu, Y., & Shu, J. (2025). The Effect of Drama Education on Enhancing Critical Thinking Through Collaboration and Communication. Education Sciences, 15(5), 565. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050565