An Examination of the Professional Learning Needs of SENCOs as Strategic Leaders in Primary Schools in Ireland

Abstract

1. Introduction

Special Education in Ireland: Implications for SENCOs’ Professional Learning and Development

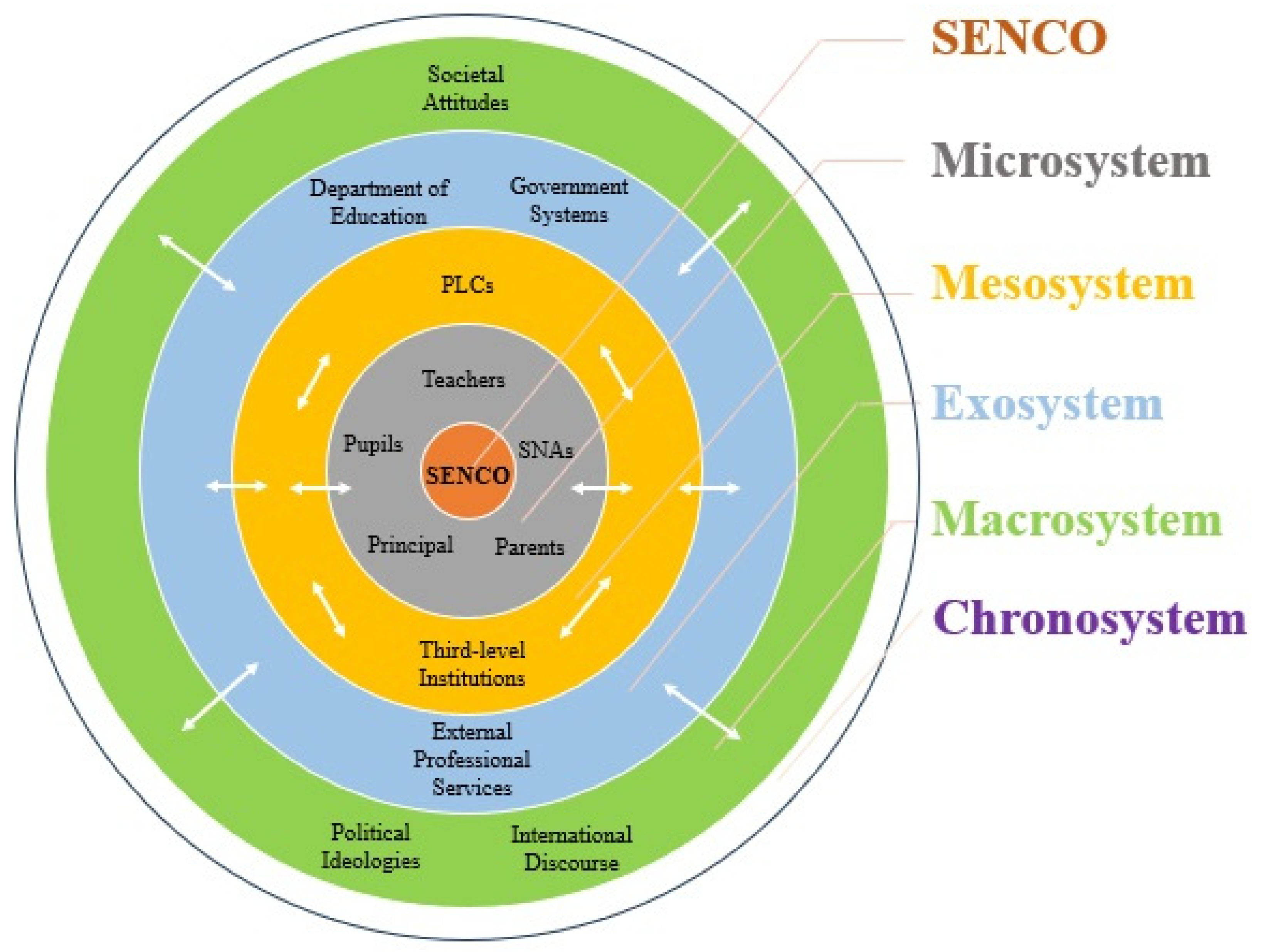

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Ecological Systems Theory

2.2. Community of Practice

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Design

3.2. Sampling

3.3. Participants

3.4. Ethics

3.5. Data Collection

3.6. Data Analysis

- Theme one: Knowledgeable SENCOs lack the opportunity for formalised SENCO-specific professional learning (48 units of meaning).

- Theme two: SENCOs learn from engagement in communities of practice (55 units of meaning).

- Theme three: There is a need for a formalised SENCO-specific professional learning programme (49 units of meaning).

3.7. Quality

3.8. Limitations

4. Results

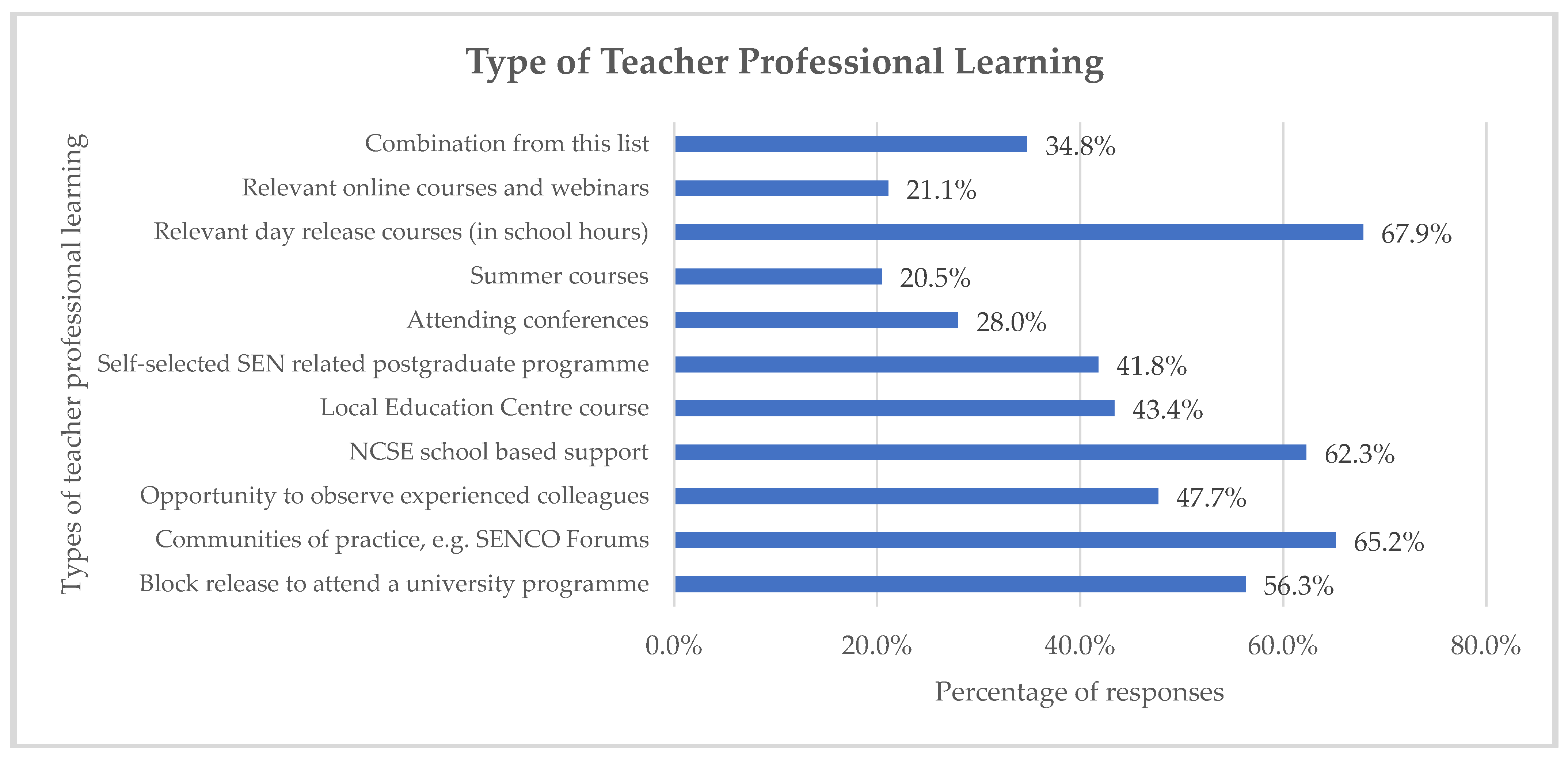

4.1. Phase One Results

4.2. Phase Two Results

4.2.1. Theme One: Knowledgeable SENCOs Lack the Opportunity for Formalised SENCO-Specific Professional Learning

I mean at any given time somebody can just pop their head in the door to say, can I just ask you? Or I have a question, or would you mind if I had a look at, that’s just constant all the time.

I think that the Department of Education needs to look at the role and identify, prioritise what the role actually is and make that specific and implement training on it.

4.2.2. Theme Two: SENCOs Learn from Engagement in Communities of Practice

I think sometimes we get the best form of learning from our colleagues, the person next door, the person who pops in for a quick piece of advice and I think the biggest challenge is offering opportunities where people can collaborate and can have those professional conversations.

There is always people to ask for help, which is great, especially with the SENCO community of practice, it’s brilliant to have other people in the same role that you can bounce ideas off or ask questions. I find that group invaluable.

Schools are so different, liaising with other SETs is really important, it is good to know how others are doing it. If you have a problem, others may have a solution or maybe they have a suggestion.

The outside speakers are brilliant, but it’s even chatting to each other and bouncing ideas off each other or asking for advice from each other because we’re all in the same boat. We all have the same kind of role, the same challenges. It’s great for ideas and for reflection for yourself.

In our group it’s what we want. It is run by teachers…it’s not imposed on us. It’s a nice way to work. It’s coming from the group, it’s intrinsic, so I think that that’s very, very good.

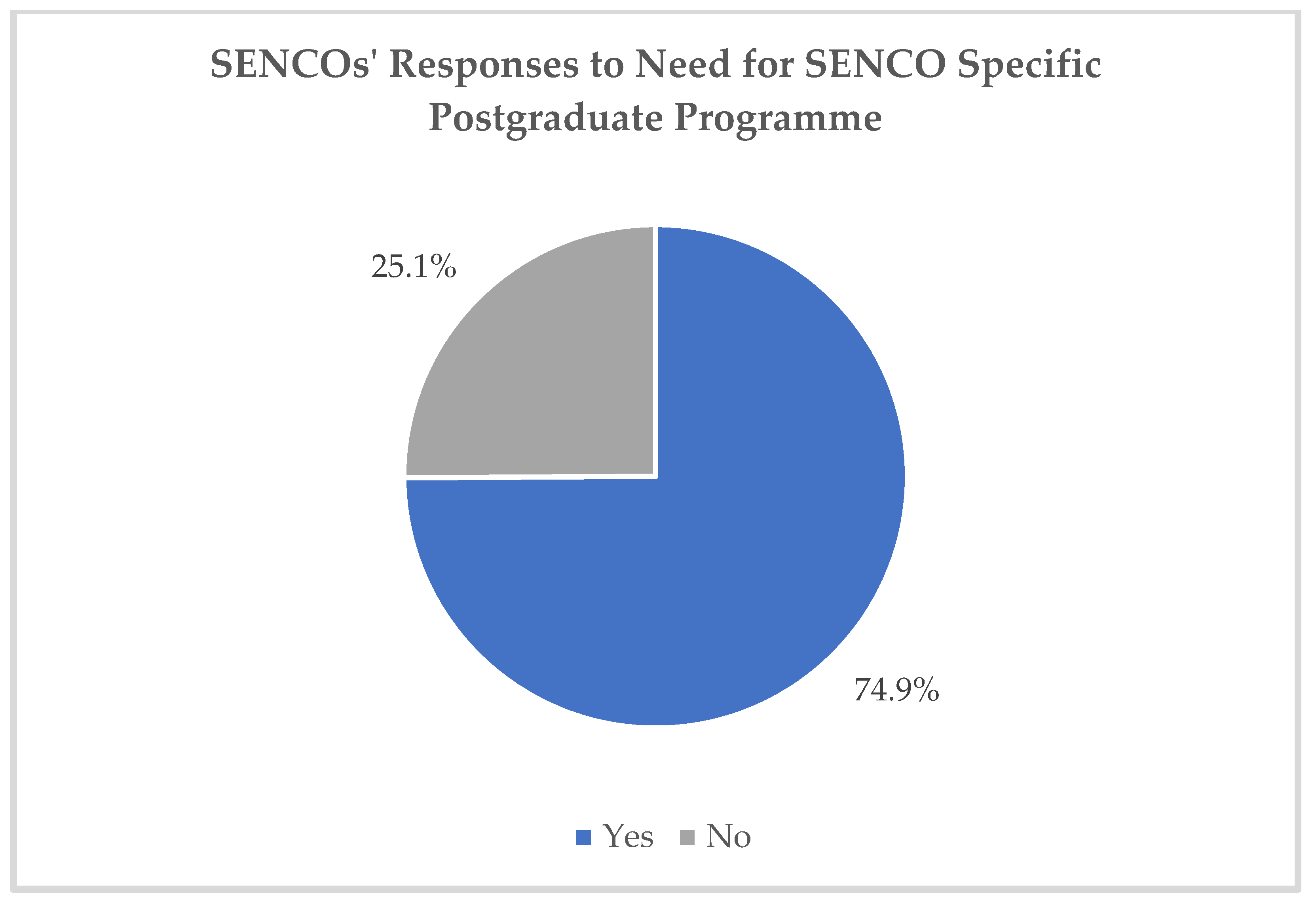

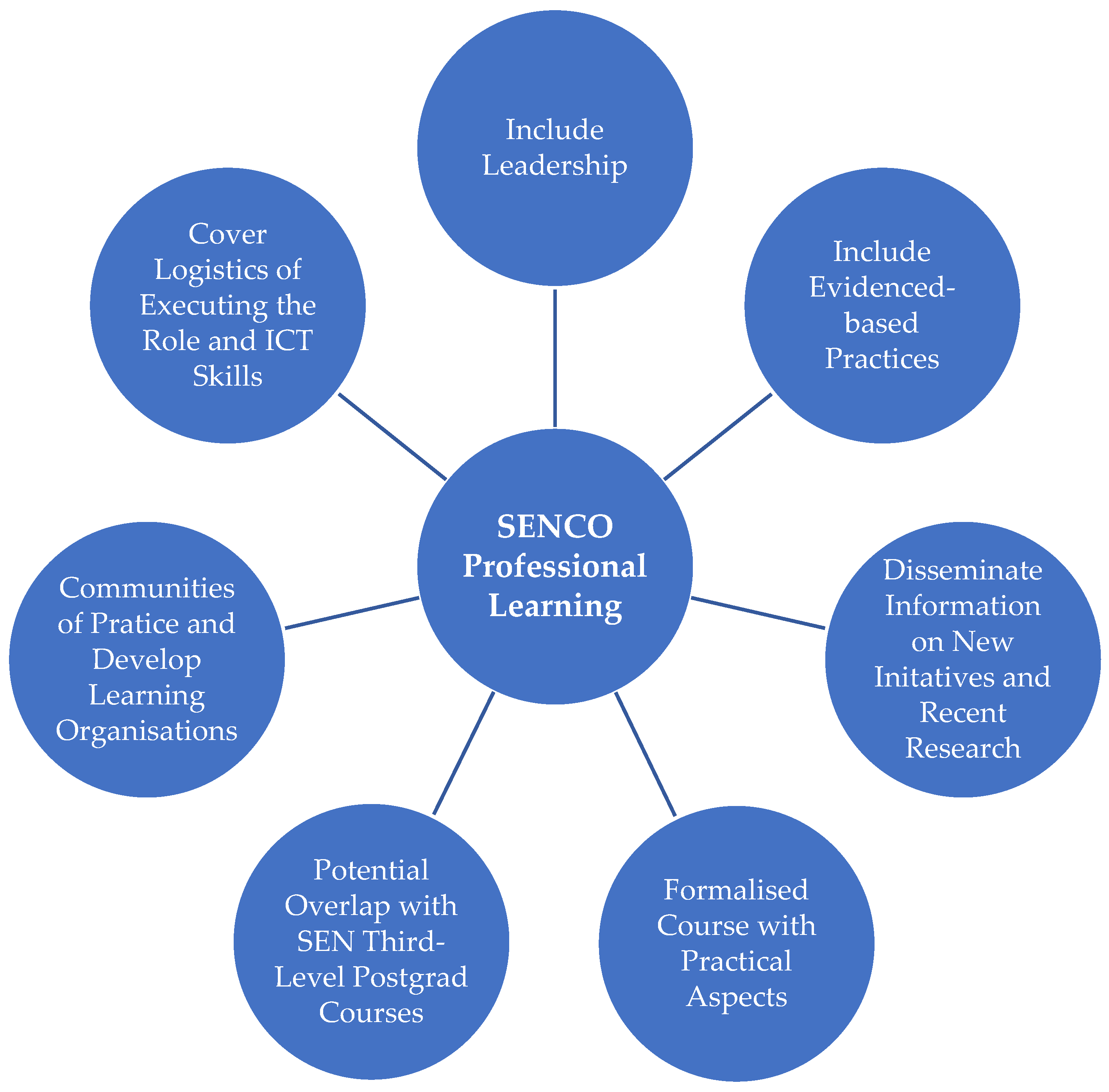

4.2.3. Theme Three: There Is a Need for a Formalised SENCO-Specific Professional Learning Programme

I think the role is very specific and it is ever changing…The SENCO has a big leadership role, they are convincing other people, they are leading in the area of SEN and they are working on best practice. I think that would be very important.

You are getting the best of the best in them (third-level institutions), the newest initiatives that are on stream. You are getting best practice. You are getting things that are evidence based, so I think that is so important to know. It’s coming from the experts, these people that are reading the research, and then it’s the only way to disseminate it into schools by doing a course on this.

There is definitely a need for some type of course for SENCO duties, definitely. It has to be specific for SENCOs and be aligned with the Irish curriculum and all the inclusiveness that is out there. Also look at the whole logistics of carrying out the role, you need a huge skill set. And also in the area of ICT as well of streaming timetables and coordinating hours.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agaliotis, I., & Kalyva, E. (2011). A survey of Greek general and special education teachers’ perceptions regarding the role of the special needs coordinator: Implications for educational policy on inclusion and teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(3), 543–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1969). Social-learning theory of identificatory processes. In D. A. Goslin (Ed.), Handbook of socialization theory and research (pp. 213–262). Rand McNally. [Google Scholar]

- Birt, L., Scott, S., Cavers, D., Campbell, C., & Walter, F. (2016). Member checking: A tool to enhance trustworthiness or merely a nod to validation? Qualitative Health Research, 26(13), 1802–1811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research: A practical guide for beginners. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2020). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 328–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., Hayfield, N., & Terry, G. (n.d.). Doing reflexive TA. Available online: http://www.thematicanalysis.net/doing-reflexive-ta/ (accessed on 16 October 2023).

- Brennan, A. (2017). Exploring the impact of a professional learning community on teacher professional learning for inclusive practice [Unpublished doctoral thesis, Dublin City University]. Available online: https://doras.dcu.ie/21956/ (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Brennan, A., King, F., & Travers, J. (2021). Supporting the enactment of inclusive pedagogy in a primary school. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 25(13), 1540–1557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments in nature and design. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, J., & Doveston, M. (2014). Short sprint or an endurance test: The perceived impact of the National Award for Special Educational Needs Coordination. Teacher Development, 18(4), 495–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, A. L., & Done, E. J. (2021). Balancing pressures for SENCos as managers, leaders and advocates in the emerging context of the COVID-19 pandemic. British Journal of Special Education, 48(2), 157–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colum, M., & Mac Ruairc, G. (2023). “No one knows where we fit in really”: The role of the Special Education Needs Coordinator (SENCO) in primary school settings in Ireland—The case for a distributed model of leadership to support inclusion. Irish Educational Studies, 42(4), 543–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conway, P., Murphy, R., Rath, A., & Hall, K. (2009). Learning to teach and its implications for the continuum of teacher education: A nine-country cross-national study. The Teaching Council. Available online: https://www.teachingcouncil.ie/en/publications/research/documents/learning-to-teach-and-its-implications-for-the-continuum-of-teacher-education.pdf (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed-methods research (3rd ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Crowther, D., Dyson, A., & Millward, A. (2001). Supporting pupils with special educational needs: Issues and dilemmas for special needs coordinators in English primary schools. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 16(2), 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Paor, C., & Murphy, T. (2017). Teachers’ views on research as a model of CPD: Implications for policy. European Journal of Teacher Education, 41(2), 169–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Education. (2021). Data on individual schools. Available online: https://www.gov.ie/en/collection/63363b-data-on-individual-schools/ (accessed on 10 October 2022).

- Department of Education. (2024). Circular 0002/2024: The Special Education Teacher (SET) allocation model and the calculation of the SET allocation for each school from the 2024/25 school year until further notice. Department of Education. Available online: https://www.gov.ie/pdf/?file=https://assets.gov.ie/282686/7944731c-b15e-4a98-b76a-b06d899e4789.pdf#page=null (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Department of Education and Skills. (2017). Guidelines for primary schools: Supporting pupils with special educational needs in mainstream schools. Department of Education and Skills. Available online: https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/edf64-guidelines-for-primary-schools-supporting-pupils-with-special-educational-needs-in-mainstream-schools/ (accessed on 9 May 2024).

- Department of Education Inspectorate. (2022a). Looking at our school 2022: A quality framework for primary schools and special schools. Department of Education Inspectorate. Available online: https://www.gov.ie/pdf/?file=https://assets.gov.ie/232720/c8357d7a-dd03-416b-83dc-9847b99b025f.pdf#page=null (accessed on 11 December 2024).

- Department of Education Inspectorate. (2022b). School self-evaluation: Next steps September 2022–June 2026. Department of Education Inspectorate. [Google Scholar]

- Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education. Macmillan/Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dobson, G. J. (2019). Understanding the SENCo workforce: Re-examination of selected studies through the lens of an accurate national dataset. British Journal of Special Education, 46(4), 445–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson, G. J., & Douglas, G. (2018). Who would do that role? Understanding why teachers become SENCos through an ecological systems theory. Educational Review, 72(3), 298–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Done, E. J., Knowler, H., Richards, H., & Brewster, S. (2023). Advocacy leadership and the deprofessionalising of the special educational needs co-ordinator role. British Journal of Special Education, 50(2), 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Easton, L. B. (2008). From professional development to professional learning. The Phi Delta Kappan, 89(10), 755–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Agency for Special Needs and Inclusive Education. (2019). Teacher professional learning for inclusion: Literature review. Available online: https://www.european-agency.org/resources/publications/TPL4I-literature-review (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- Fitzgerald, J., & Radford, J. (2017). The SENCO role in post-primary schools in Ireland: Victims or agents of change? European Journal of Special Needs Education, 32(3), 452–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, S. (2024). Leadership for inclusive special education in Irish primary schools: An exploration of the role of the special educational needs coordinator [Doctoral Dissertation, Mary Immaculate College]. Available online: https://dspace.mic.ul.ie/handle/10395/3433 (accessed on 6 January 2025).

- Girelli, C., Bevilacqua, A., & Acquaro, D. (2019). Spotlight on the special education needs coordinator (SENCO): Why are SENCOs indispensable in today’s schools and how to support their middle level leadership. International Studies in Educational Administration (ISEA), 47(3), 88–106. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Ireland. (2025). Programme for government 2025—Securing Ireland’s future. Government of Ireland. Available online: https://www.gov.ie/pdf/?file=https://assets.gov.ie/318303/2cc6ac77-8487-45dd-9ffe-c08df9f54269.pdf#page=null (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Hallett, F. (2022). Can SENCOs do their job in a bubble? The impact of Covid-19 on the ways in which we conceptualise provision for learners with special educational needs. Oxford Review of Education, 48(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallett, F., & Hallett, G. (2010). Transforming the role of the SENCO. McGraw-Hill Education. [Google Scholar]

- Hallett, F., & Hallett, G. (2017). Transforming the role of the SENCO (2nd ed.). Open University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hornby, G. (2015). Inclusive special education: Development of a new theory for the education of children with special educational needs and disabilities. British Journal of Special Education, 42(3), 234–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearns, H. (2005). Exploring the experiential learning of special educational needs co-ordinators. Journal of In-Service Education, 31(1), 131–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, A. (2014). Understanding continuing professional development: The need for theory to impact on policy and practice. Professional Development in Education, 40(5), 688–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, F. (2014). Evaluating the impact of teacher professional development: An evidence-based framework. Professional Development in Education, 40(1), 89–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- McElearney, A., Murphy, C., & Radcliffe, D. (2018). Identifying teacher needs and preferences in accessing professional learning and support. Professional Development in Education, 45(3), 433–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mertens, D. M. (2019). Research and evaluation in education and psychology: Integrating diversity with quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-methods (5th ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Mockler, N. (2005). Trans/Forming teachers: New professional learning and transformative teacher professionalism. Journal of In-service Education, 31(4), 733–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mockler, N. (2013). Teacher professional learning in a neoliberal age: Audit, professionalism and identity. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 38(10), 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Council for Special Education. (2024). An inclusive education for an inclusive society. NCSE. Available online: https://ncse.ie/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/NCSE-An-Inclusive-Education-A5-Proof-07WEB.pdf (accessed on 25 November 2024).

- O’Gorman, E., & Drudy, S. (2011). Professional development for teachers working in the area of special education/inclusion in mainstream schools: The views of teachers and other stakeholders. National Council for Special Education. Available online: http://ncse.ie/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Professional_Development_of_Teachers.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2023).

- Qualtrics. (2022). Sample size calculator and complete guide. Available online: https://www.qualtrics.com/blog/calculating-sample-size/ (accessed on 12 August 2022).

- Raftery, A. (2021). Leading the special education teacher allocation model: Examining the perspectives and experiences of school leaders in supporting special and inclusive education in Irish primary schools. Journal of Inclusive Education in Ireland, 34(2), 2–20. [Google Scholar]

- Richards, H. (2023). SENCo professional identity and development. In H. Knowler, H. Richards, & S. Brewster (Eds.), Developing your expertise as a SENCo: Leading inclusive practice. Critical Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Robson, C. (2011). Real world research: A resource for social-scientists and practitioner-researchers (3rd ed.). Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Schön, D. A. (2017). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Senge, P. M., Cambron-McCabe, N., Lucas, T., Smith, B., Dutton, J., & Kleiner, A. (2000). Schools that learn: A fifth discipline fieldbook for educators, parents and everyone who cares about education. Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- Swaffield, S., & MacBeath, J. (2009). Leadership for learning. In J. MacBeath, & N. Dempster (Eds.), Connecting leadership and learning: Principles for practice (pp. 32–53). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- The Teaching Council. (2016). Cosán: Framework for teachers’ learning, Kildare: The teaching council. Available online: https://www.teachingcouncil.ie/en/publications/teacher-education/cosan-framework-for-teachers-learning.pdf (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- Timperley, H. (2011). Realizing the power of professional learning. McGraw-Hill Education. [Google Scholar]

- Timperley, H., Wilson, A., Barrar, H., & Fung, I. (2007). Teacher professional learning and development: Best evidence synthesis iteration. New Zealand Ministry of Education. [Google Scholar]

- Vermunt, J. D., Vrikki, M., van Halem, N., Warwick, P., & Mercer, N. (2019). The impact of lesson study professional development on the quality of teacher learning. Teaching and Teacher Education, 81, 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vygotsky, L. S., & Cole, M. (1978). Mind in society: Development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, C. (2023). Creating opportunities for professional learning in SEN. Learn, 44, 45–66. [Google Scholar]

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning and identity. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Winwood, J. (2013). Policy into practice: The changing role of the special educational needs coordinator in England [Unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Birmingham]. Available online: https://etheses.bham.ac.uk/id/eprint/3981/1/Winwood13EdD.pdf (accessed on 17 October 2024).

| Programme Components | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|

| Teaching strategies for students with SEN | 1.26 | 0.49 |

| Developing alternative curriculum for students with SEN, e.g., evidence-based strategies | 1.29 | 0.53 |

| Identifying pupils whose needs require support at level 2 or 3 on the continuum of support | 1.31 | 0.53 |

| Co-ordinating SEN teams and school supports, e.g., SNAs | 1.36 | 0.60 |

| Inclusion of pupils with SEN into mainstream classes | 1.36 | 0.61 |

| Monitoring of pupil progress | 1.36 | 0.54 |

| Learning difficulties: types, characteristics and assessment | 1.36 | 0.60 |

| Effective allocation and timetabling of SEN provision | 1.37 | 0.61 |

| Developing skills in collaborating with others, e.g., teachers and the senior leadership team | 1.38 | 0.59 |

| Working with parents of children with SEN | 1.39 | 0.58 |

| Psychological assessments: types, characteristics and assessment | 1.41 | 0.63 |

| School policy and planning in SEN | 1.42 | 0.61 |

| Working with external agencies/ support services for SEN, e.g., OT | 1.42 | 0.60 |

| Inclusive policies | 1.47 | 0.65 |

| Mentoring and coaching of SEN staff | 1.48 | 0.66 |

| Co-teaching: types and effective implementation | 1.51 | 0.71 |

| Standardised tests, diagnostic tests, and cognitive assessments (paper-based and online) | 1.54 | 0.70 |

| Administration, record-keeping, and digital literacy skills | 1.58 | 0.72 |

| Contemporary issues in inclusive and special education | 1.61 | 0.73 |

| Supporting pupils’ transitions to and from primary school | 1.63 | 0.72 |

| Leadership and management in education | 1.64 | 0.83 |

| The law and special education needs | 1.68 | 0.80 |

| Information, communication and assistive technology | 1.72 | 0.75 |

| Establishing and coordinating special classes | 1.80 | 0.96 |

| Identifying relevant CPD and providing CPD to staff | 1.83 | 0.79 |

| Theoretical concepts relating to inclusive and special education | 1.86 | 0.82 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gallagher, S.; Fitzgerald, J. An Examination of the Professional Learning Needs of SENCOs as Strategic Leaders in Primary Schools in Ireland. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 564. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050564

Gallagher S, Fitzgerald J. An Examination of the Professional Learning Needs of SENCOs as Strategic Leaders in Primary Schools in Ireland. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(5):564. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050564

Chicago/Turabian StyleGallagher, Sarah, and Johanna Fitzgerald. 2025. "An Examination of the Professional Learning Needs of SENCOs as Strategic Leaders in Primary Schools in Ireland" Education Sciences 15, no. 5: 564. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050564

APA StyleGallagher, S., & Fitzgerald, J. (2025). An Examination of the Professional Learning Needs of SENCOs as Strategic Leaders in Primary Schools in Ireland. Education Sciences, 15(5), 564. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15050564