Partnerships as Professional Learning: Early Childhood Teaching Assistants’ Role Development and Navigation of Challenges Within a Culturally Responsive Robotics Program

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Teaching Assistants and Early Care

1.2. Study Purpose

1.3. Educator Voice in Partnerships

1.4. Intersectional Perspectives

1.5. Practitioner Inquiry and Critical Reflection

1.6. Educators and RPPs

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Background of the Family–School–University Partnership

2.2. Participants

2.3. Design-Based Research

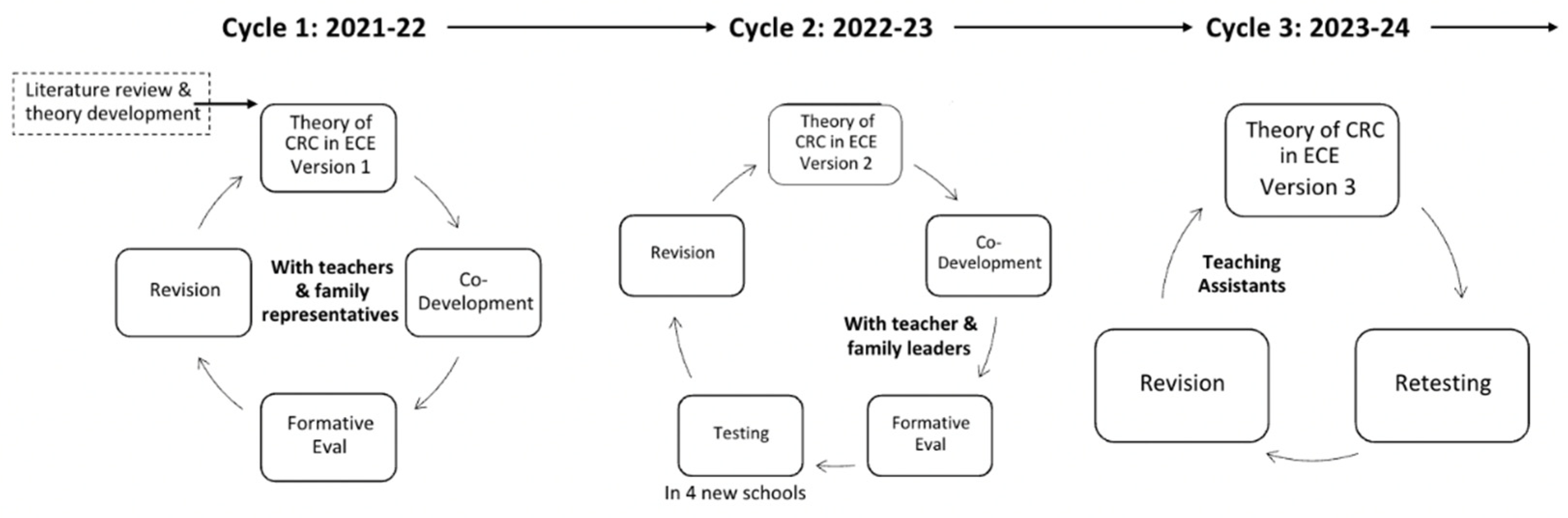

2.4. Professional Learning Opportunities

2.5. Data Collection

2.6. Professional Learning Session 1

2.7. Professional Learning Session 2

2.8. Data Analysis

3. Results

And I think that I feel like an actual teacher when I do CRRAFT. And because I had my classes at the university. I feel like when we’re learning about something, and we have to have evidence I do when I do CRRAFT. I use my CRRAFT [experiences] as my evidence practice with my students. Like, oh, we did robots today. This is what I did in my small group, all of my lab experience has been teaching CRRAFT.

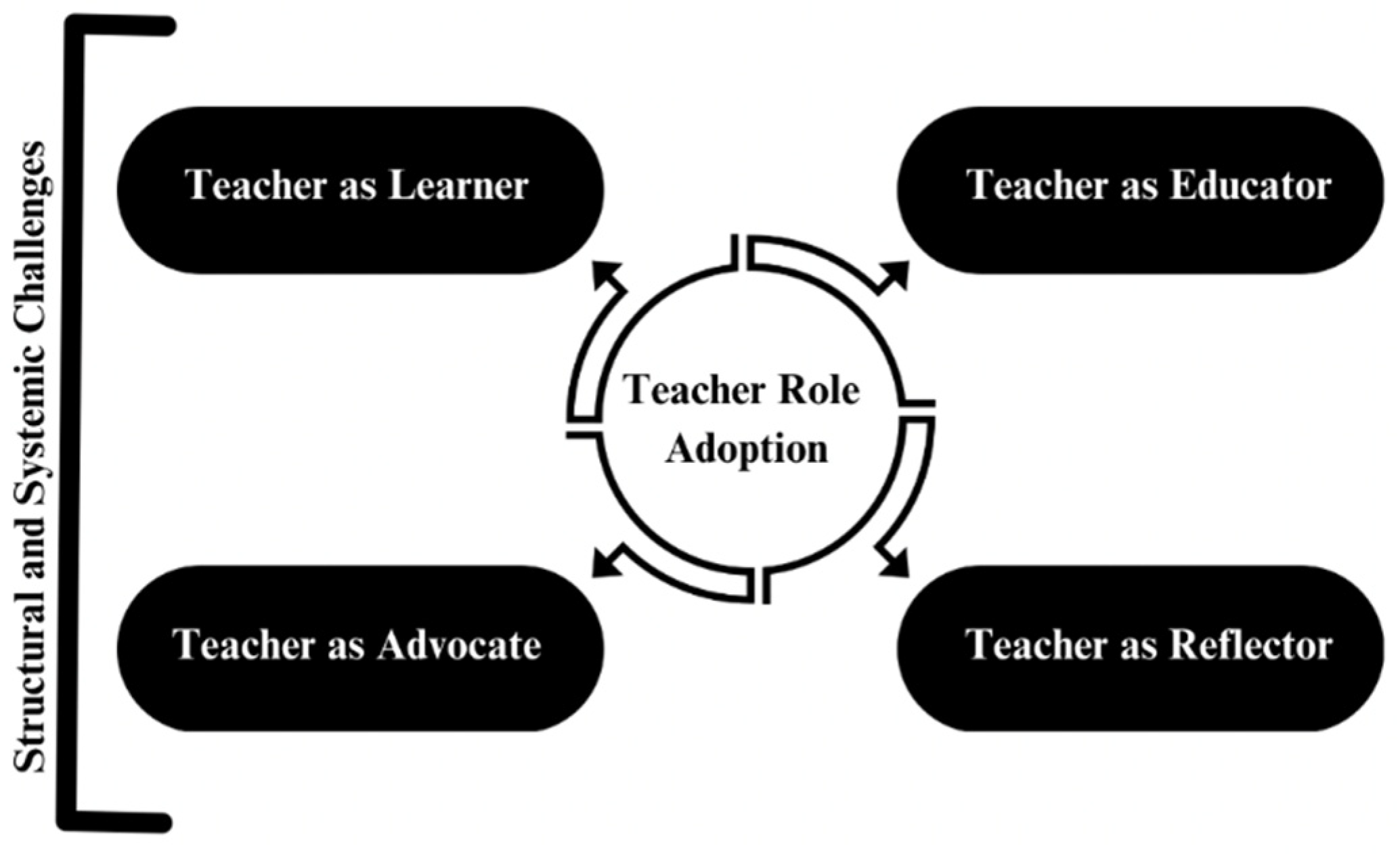

3.1. Structural and Systemic Challenges

3.2. I Don’t Want to Leave, but Something Is Pulling Me to—Mrs. Davis

3.3. Teacher as Advocate—Mrs. Davis

So I mean, I don’t want to leave [it] seems like something is just pulling at me too. Yeah, yeah, I don’t want to, but then to know too, honey it might be a whole new staff again who knows. And so, and I’m not going to go in again next year and set up a whole classroom again. I’m not going to do that.

So let’s say when I went back to work I did not have a teacher right? I had to set up the whole classroom by myself. Yeah, I had to go out and spend my own money to buy everything that I needed for the classroom, bulletin boards, everything. And I didn’t get a teacher until September the 18th. Nobody reimbursed or anything.

3.4. Teacher as Reflector—Mrs. Davis

It’s hard for young children to understand it, all right. It’s hard for them to understand...those are my husband’s caregivers. So I don’t work Mondays…I work all day Wednesdays. Thursday I will be [at school] and I work all day Friday…So they know my schedule and I’m glad, you know, because I hate to do it like this…but I couldn’t do it any other way.

[We] built a robot and they got to help me [however they wanted]. We introduced them to the recyclables in my small group after we did it as a large group. And then they kind of helped me pick the objects for certain parts of the robot. But yeah, like that’s how we kind of introduce the whole concept of building the robot. So I learned and I got cans from the cafeteria, the large vegetable and fruit cans that they have, I got those from them and we use all that kind of stuff.

3.5. I Mean You’re Just a Teaching Assistant—Callie

I started CRRAFT last year and they did a whole meeting with the [lead] teachers at the beginning of the school year. And all the [lead] teachers, especially the new teachers who started, who had never been introduced to it. And they said that the teaching assistants would go at a later date, that date never came, we never got a meeting. I never got to go and learn how to use the materials. So my teacher Autumn had to teach me, or I just read the lessons and I’ve read the book, the CRRAFT book [a binder set up for each teacher with the needed materials.

But I feel like I enjoyed [the] CRRAFT a lot more last year than I have this year. But now no one’s really come into our classroom this year to help, and it’s mostly because of our schedule and our schedule has changed. Like now. So no one schedule can work with the time we do our CRRAFT activities.

And so for a while we didn’t do it. So my kids had a huge gap where we stopped at phase three and we haven’t moved on because we were supposed to be doing only curriculum and practice only for small groups. Only when we need something extra to add there to the so I haven’t really gotten to do much, but now we’re on phase four. We just started yesterday, so I was like, I would really like to finish this. I need to finish it. They need to finish the stuff they have learned.

3.6. What I Bring Home Is Not Livable—Callie

I know that we make more than a step zero in the cafeteria, but after they reach step one, they make more than we do. Help us. And that’s in the cafeteria. They’re starting to up the cafeteria [staff]. They need to start looking at [teaching assistant] pay.

3.7. We Play All Day—That’s What Everybody Says Here—Nora

So in like the 90s, early 2000, a teaching assistant made copies, laminated, and cut stuff. That is no longer the deal. Nor has it been for the past 10, 15, maybe 20 years.

We have two or three small groups everyday. And we have days where you’re given a book with curriculum and it’s yours you’re in charge of teaching them. Those kids are tested every two weeks on the computer, and they are looked at [like] data. Like you’re responsible for it. It’s not like you can sit there and just play around for thirty minutes.

No, no [laughs]. We play all day. That’s what everybody here says. I wish we could play all day. And I’m like ya’ll have no idea. Mrs. Davis responded by sharing, it’s like either that or they’re just like, I could never do it.

3.8. Advocating for Self—Nora

These are our COVID babies. Like they were born when the world shut down. And so we have three kids whose birthdays were in March. And I was like, wow, they were all born in March of 2020. That is literally when we shut down. I couldn’t imagine being a mom at that moment.

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications

4.2. Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Code | Definition | Example Excerpt |

|---|---|---|

| Educator as reflector | When educators share about their past experiences with the CRRAFT partnership. | Educator: “You know, all the whole team. And back when I started, the teacher, my teacher partner that I was working with then, you know, we had a lot of meetings and stuff and then we had to go to over to, you know, UNIVERSITY. And I enjoyed all that because getting together with everybody that was on the team and meeting people.” |

| Structural, systemic challenges | References and reflections about known structural and systemic barriers to the early care and education workforce (i.e., working more than one job, pay inequities). | Educator: “No, no [laughs]. We play all day. That’s what everybody here says. I wish we could play all day. And I’m like ya’ll have no idea.” |

| This also includes information about their home lives—i.e., not being able to pay bills or livable wages. | Educator: “It’s like either that or they’re just like, I could never do it.” | |

| Educator: “They’re just so little. I just couldn’t do it.” | ||

| This includes statements that affect both lead teachers and educational assistants and the ECE field generally, i.e., “I feel like there was a shift in education from 1999 to 2001.” | Educator: “So I mean, I don’t want to leave [it] seems like something is just pulling at me too. Yeah, yeah, I don’t want to, but then to know too, honey it might be a whole new staff again who knows. And so, and I’m not going to go in again next year and set up a whole classroom again. I’m not going to do that.” | |

| Positive reflections | Positive reflections about the workforce. | Educator: “And I think that I feel like an actual teacher. I do CRRAFT and because I had my classes at [the] UNIVERSITY. I feel like when we’re learning about something and we have to evidence for something, when I do CRRAFT, I use my CRRAFT as evidence practice with my students. Like, oh, we did robots today. This is what I did in my small group, all of my lab experience has been teaching CRRAFT.” |

| Reflections structural barriers to teaching assistants | These are structural or social barriers within school systems that affect educational assistants’ experiences or abilities to advocate for themselves. | Educator: “I know that we make more than a step zero in the cafeteria, but after they reach step one, they make more than we do. Help us. And that’s in the cafeteria. They’re starting to up the cafeteria. They need to start looking at [educational assistant] pay.” |

| Teacher as advocate | When educators are revoicing and encouraging peers to advocate for themselves, peers, and children. Or the educators are advocating for themselves and their experiences in the partnership. | Educator: “Again, your admin needs to be advocating for your parents to come pick up on time.” |

| Teacher as educator | Teacher provides practical strategies/instruction about program to others; this also includes when they share about how children engage in the program activities (e.g., “the children were intrigued to see how the mouse would move if they clicked the right arrow button twice.”) | Educator: “And I introduced it to a small group. That’s where I’d sit on the floor, you know, with each group, everybody had a chance to program it out of [this] many blocks, you know, use that one to start. I use one blue, one red, and one yellow. And in the end, everyone got a chance to program and do what they did with the blocks, you know, mix them up or whatever.” |

| Teacher as co-designer | Teacher as co-designer with university partners; provides input from practice on re-design; adapts design to fit local context. | Educator: “Like along with everything’s a little bit different video because all everybody is all over and its big you know it’s just a mess. So, you would like to meet more often than just once per phase?” |

| Teacher as decision maker | Teacher shares decisions or choices regarding CRR program participation or implementation that supports development of epistemic agency and authority; typically focused on self or self in relation to others (e.g., “I haven’t really explored the code-a-pillar at all, but I have been using the robot mice often.”) OR (i.e., “And I enjoyed all that because getting together with everybody that was on the team and meeting people but now, I mean, it’s like, I don’t know, we didn’t have that kind of connection anymore to me.” | Educator: “And so for a while we didn’t do it. So, my kids had a huge hap where we stopped at phase three, and we haven’t moved on because it was [when] we were supposed to be doing only curriculum and practice only for small groups. Only when we need something extra to add there to and so I haven’t gotten to do much, but now we’re on phase four. We just started yesterday, so I was like, I would really like to finish it. They need to finish the stud they have learned.” |

| Teacher as advisor for design/implementation | Teacher provides direct feedback about program design/implementation that may or may not include suggestions. (“is there a way to integrate the suggested plans into the lesson plans already being used and connect to standards?”) | Educator: “I also wanted to say that I know all of the [lead] teachers got to do like a big [training] at the beginning of the year, but it would have been nice to have one. So, I knew what was happening. Like we could, it would be more beneficial for us to have one to if we’ve going to help [lead] small groups.” |

| Teacher as leader | Teacher engages as leader in formal or informal contexts (e.g., “T06 suggests it would still be helpful to break into smaller groups to plan out sequences rather than completing as a single group. T06 states “it would lead to richer discussions” when we return as a large group and discuss differences between groups’ sequences”). | Educator: “No, no, no, lord, no. So, let’s say when I went back to work, I did not have a teacher right? I had to set up the whole classroom by myself. Yeah, I had to go out and spend my own money to buy everything that I needed for the classroom, bulletin boards, and everything. And I didn’t get a teacher until September the 18th. Nobody reimbursed, or anything.” |

| Teacher as learner | Teacher engages as learner in formal or informal contexts. | Educator: “I started the CRRAFT last year and they did a whole meeting with the teachers at the beginning of the school year. And all the teachers especially the new teachers who started, who had never been introduced to it. And they said that the teaching assistants would go at a later date, that day never came, we never got a meeting. I never got to go and learn how to use the materials. So my teacher Autumn had to teach me, or I just read the lessons and I’ve read the book, the CRRAFT book [a binder set up for each teacher with the needed materials].” |

References

- Armstrong, M., Dopp, C., & Welsh, J. (2020). Design-based research. In The students’ guide to learning design and research (pp. 1–6). EdTech Books. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson, B. M., & Rosiek, J. (2008). Researching and representing teacher voice (s): A reader response approach. In Voice in qualitative inquiry (pp. 187–208). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Barenthien, J., Oppermann, E., Anders, Y., & Steffensky, M. (2020). Preschool teachers’ learning opportunities in their initial teacher education and in-service professional development–do they have an influence on preschool teachers’ science-specific professional knowledge and motivation? International Journal of Science Education, 42(5), 744–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassok, D., Latham, S., & Rorem, A. (2016). Is kindergarten the new first grade? AERA Open, 2(1), 2332858415616358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassok, D., Markowitz, A. J., Bellows, L., & Sadowski, K. (2021). New evidence on teacher turnover in early childhood. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 43(1), 172–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2022). Conceptual and design thinking for thematic analysis. Qualitative Psychology, 9(1), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, D., Yazejian, N., Jang, W., Kuhn, L., Hirschstein, M., Hong, S. L. S., Stein, A., The Educare Learning Network Investigative Team, Bingham, G., Carpenter, K., Cobo-Lewis, A., Encinger, A., Fender, J., Green, S., Greenfield, D., Harden, B. J., Horm, D., Jackson, B., Jackson, T., … Wilcox, J. (2023). Retention and turnover of teaching staff in a high-quality early childhood network. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 65, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brydon-Miller, M., & Maguire, P. (2009). Participatory action research: Contributions to the development of practitioner inquiry in education. Educational Action Research, 17(1), 79–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryk, A. S. (2017). Accelerating how we learn to improve. Education Didactique, 11(2), 11–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cane, J., O’Connor, D., & Michie, S. (2012). Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implementation Science, 7, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caudle, L. A., Harper, F. K., Quinn, M. F., & Greene, D. (2021). Co-constructing and sharing STEAM knowledge through a culturally relevant literacy-based early childhood school-university partnership. In The Organizing Committee of the 2nd International Conference of the Journal Scuola Democratica (Ed.), Proceedings of the second international conference of scuola democratica reinventing education: Learning with new technologies, equality, and inclusion (Vol. II, pp. 667–678). Associazione “Per Scuola Democratica”. Available online: https://www.scuolademocratica-conference.net/proceedings-2/ (accessed on 22 December 2024).

- Caudle, L. A., Moran, M. J., & Hobbs, M. K. (2014). The potential of communities of practice as contexts for the development of agentic teacher leaders: A three-year narrative of one early childhood teacher’s journey. Action in Teacher Education, 36(1), 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caudle, L. A., Quinn, M. F., Harper, F. K., Thompson, H. R., Rainwater, T. R., & Flowers, C. E., Jr. (2024). “Any other thoughts?”: Establishing third space in a family-school-university STEM partnership to center voices of parents and teachers. Peabody Journal of Education, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2017). Thematic analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(3), 297–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, L. (2007). Is there really a second shift, and if so, who does it? A time-diary investigation. Feminist Review, 86(1), 149–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, T., & Cappella, E. (2019). Who are they and what do they need: Characterizing and supporting the early childhood assistant teacher workforce in a large urban district. American Journal of Community Psychology, 63(3–4), 312–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, K. W. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics (pp. 139–167). University of Chicago Legal Forum. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, K. W. (1994). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color: The public nature of private violence. In M. Albertson Fineman, & R. Mykitiuk (Eds.), Women and the discovery of abuse. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- CSCCE. (2022). Child care teachers are essential workers-let’s treat them that way. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment. Available online: https://cscce.berkeley.edu/publications/infographic/child-care-teachers-are-essential-workers-lets-treat-them-that-way/ (accessed on 28 December 2024).

- Datnow, A., Guerra, A. W., Cohen, S. R., Kennedy, B. C., & Lee, J. (2023). Teacher sensemaking in an early education research–practice partnership. Teachers College Record, 125(2), 66–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Los Santos, R., Borchardt PsyD, J. N., Yousey, B., Dickson, S., Aloise, S., Butler, M., & Banker Ed D, D. (2023). A narrative review of preschool teacher burnout. Modern Psychological Studies, 29(2), 1. [Google Scholar]

- Dhamoon, R. K. (2011). Considerations on mainstreaming intersectionality. Political Research Quarterly, 64(1), 230–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, C. C., Harrison, C., & Coburn, C. E. (2019). “What the hell is this, and who the hell are you?” Role and identity negotiation in research-practice partnerships. AERA Open, 5(2), 2332858419849595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, C. C., Penuel, W. R., Allen, A., Anderson, E. R., Bohannon, A. X., Coburn, C. E., & Brown, S. L. (2022). Learning at the boundaries of research and practice: A framework for understanding research–practice partnerships. Educational Researcher, 51(3), 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrell, C. C., Singleton, C., Stamatis, K., Riedy, R., Arce-Trigatti, P., & Penuel, W. R. (2023). Conceptions and practices of equity in research-practice partnerships. Educational Policy, 37(1), 200–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall-Kenyon, K. M., Bullough, R. V., MacKay, K. L., & Marshall, E. E. (2014). Preschool teacher well-being: A review of the literature. Early Childhood Education Journal, 42(3), 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hancock, A. M. (2007). Intersectionality as a normative and empirical paradigm. Politics & Gender, 3(2), 248–254. [Google Scholar]

- Harper, F. K., Caudle, L. A., Flowers, C. E., Jr., Rainwater, T., Quinn, M. F., & The CRRAFT Partnership. (2023). Centering teacher and parent voice to realize culturally relevant teaching of computational thinking in early childhood. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 64, 381–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrick, E., Cobb, P., Penuel, W. R., Jackson, K., & Clark, T. (2017). Assessing research-practice partnerships: Five dimensions of effectiveness. William T. Grant Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Henrick, E., Farrell, C. C., Singleton, C., Resnick, A. F., Penuel, W. R., Arce-Trigatti, P., Schmidt, D., Sexton, S., Stamatis, K., & Wellberg, S. (2023). Indicators of research-practice partnership health and effectiveness: Updating the five dimensions framework. National Center for Research in Policy and Practice and National Network of Education Research-Practice Partnerships. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiung, P. C. (2008). Teaching reflexivity in qualitative interviewing. Teaching Sociology, 36(3), 211–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Im, H. (2021). Kindergarten assessment policies and reading growth during the first two years: Does standardized assessment policy benefit children who are left behind? Learning and Individual Differences, 86, 101977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y., Austin, L. J. E., & Hess, H. (2024). The multilayered effects of racism on early educators in California. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment. Available online: https://cscce.berkeley.edu/publications/report/effects-of-racism-on-california-early-educators/ (accessed on 27 December 2024).

- Kim, Y., Montoya, E., Doocy, S., Austin, L. J., & Whitebook, M. (2022). Impacts of COVID-19 on the early care and education sector in California: Variations across program types. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 60, 348–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuh, L. P. (2012). Promoting communities of practice and parallel process in early childhood settings. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 33(1), 19–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laughlin, L. M. (2021). Third space, partnerships, & clinical practice: A literature review. Professional Educator, 44(1), 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Lezotte, S., Krishnamurthy, S., Tulino, D., & Zion, S. (2022). Finding the heart of a research-practice partnership: Politicized trust, mutualism, and use of research. Improving Schools, 25(2), 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, B., & Deacon, M. (2024). Teacher practitioner enquiry: A process for developing teacher learning and practice? Educational Action Research, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzei, L. A., & Jackson, A. Y. (2008). Introduction: The limit of voice. In Voice in qualitative inquiry (pp. 13–26). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- McGrath, R. (2021). Journaling and memoing: Reflexive qualitative research tools. In Handbook of qualitative research methodologies in workplace contexts (pp. 245–262). Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- McLean, C., Austin, L. J., Whitebook, M., & Olson, K. L. (2021). Early childhood workforce index 2020. Center for the Study of Child Care Employment, University of California, Berkeley. [Google Scholar]

- Mercer-Mapstone, L., Islam, M., & Reid, T. (2021). Are we just engaging ‘the usual suspects’? Challenges in and practical strategies for supporting equity and diversity in student–staff partnership initiatives. Teaching in Higher Education, 26(2), 227–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mowrey, S. C., & Farran, D. C. (2022). Teaching teams: The roles of lead teachers, teaching assistants, and curriculum demand in pre-kindergarten instruction. Early Childhood Education Journal, 50(8), 1329–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penuel, W. R., & Hill, H. C. (2019). Building a knowledge base on research-practice partnerships: Introduction to the special topic collection. AERA Open, 5(4), 2332858419891950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Press, F., Bittman, M., Harrison, L. J., Brown, J. E., Wong, S., & Gibson, M. (2024). Discovering the hidden work of commodified care: The case of early childhood educators. Social Sciences, 13, 625. [Google Scholar]

- Pugach, M. C., Gomez-Najarro, J., & Matewos, A. M. (2019). A review of identity in research on social justice in teacher education: What role for intersectionality? Journal of Teacher Education, 70(3), 206–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quinn, M. F., & Thompson, H. R. (2023, April 13–16). “Saying ‘good job’ is not enough”: ECE Administrators’ perceptions of teachers’ professional development [Conference presentation]. American Education Research Association, Chicago, IL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Razaghi, N., Abdolrahimi, M., & Salsali, M. (2015). Memo and memoing in qualitative research: A narrative review. Journal of Qualitative Research in Health Sciences, 4(2), 206–217. [Google Scholar]

- Schaack, D. D., Donovan, C. V., Adejumo, T., & Ortega, M. (2022). To stay or to leave: Factors shaping early childhood teachers’ turnover and retention decisions. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 36(2), 327–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sjölund, S., Lindvall, J., Larsson, M., & Ryve, A. (2022). Mapping roles in research-practice partnerships—A systematic literature review. Educational Review, 10(1), 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sosinsky, L. S., & Gilliam, W. S. (2011). Assistant teachers in prekindergarten programs: What roles do lead teachers feel assistants play in classroom management and teaching? Early Education & Development, 22(4), 676–706. [Google Scholar]

- Swain, J. (2018). A hybrid approach to thematic analysis in qualitative research: Using a practical example. Sage Research Methods. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, L. (2013). Lived childhood experiences: Collective storytelling for teacher professional learning and social change. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 38(3), 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, H. R., Caudle, L. A., Grist, C. L., Harper, F. K., & Quinn, M. F. (2024, March 22–23). Understanding ECE teaching assistants experiences within the context of research-practice partnerships [Conference presentation]. Texas Early Childhood Summit, College Station, TX, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Vetter, A., Faircloth, B. S., Hewitt, K. K., Gonzalez, L. M., He, Y., & Rock, M. L. (2022). Equity and social justice in research practice partnerships in the United States. Review of Educational Research, 92(5), 829–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisenfeld, G. G., Hodges, K. S., & Copeman Petig, A. (2023). Qualifications and supports for teaching teams in state-funded preschool in the United States. International Journal of Child Care and Education Policy, 17(1), 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitebook, M., Sakai, L., Kipnis, F., Lee, Y., Bellm, D., Almaraz, M., & Tran, P. (2006). California early care and education workforce study: Licensed child care centers, statewide 2006. Center for the Study of Childcare Employment. [Google Scholar]

- Whyte, K. L., & Coburn, C. E. (2022). Understanding kindergarten readiness. The Elementary School Journal, 123(2), 344–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W., & Zammit, K. (2020). Applying thematic analysis to education: A hybrid approach to interpreting data in practitioner research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 1609406920918810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Educator | Mrs. Davis | Callie | Nora |

| Age | 70–75 | 35–40 | 30–35 |

| Race/Ethnicity | Black | White | White |

| Higher Education | Some higher education credits | Associates, working towards Pre-K-3 Bachelors | Some higher education credits |

| Years in PARTNERSHIP | Three years | Two years | Two years |

| Years in ECE | 30 or more | Less than 5 | Less than 5 |

| Type of School | Pre-kindergarten classroom within a Pre-K school. | Stand-alone pre-kindergarten classroom within a Pre-K-5 school. | Stand-alone pre-kindergarten classroom within a Pre-K-5 school. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Thompson, H.R.; Caudle, L.A.; Harper, F.K.; Quinn, M.F.; Avin, M.K.; The CRRAFT Partnership. Partnerships as Professional Learning: Early Childhood Teaching Assistants’ Role Development and Navigation of Challenges Within a Culturally Responsive Robotics Program. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 514. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040514

Thompson HR, Caudle LA, Harper FK, Quinn MF, Avin MK, The CRRAFT Partnership. Partnerships as Professional Learning: Early Childhood Teaching Assistants’ Role Development and Navigation of Challenges Within a Culturally Responsive Robotics Program. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(4):514. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040514

Chicago/Turabian StyleThompson, Hannah R., Lori A. Caudle, Frances K. Harper, Margaret F. Quinn, Mary Kate Avin, and The CRRAFT Partnership. 2025. "Partnerships as Professional Learning: Early Childhood Teaching Assistants’ Role Development and Navigation of Challenges Within a Culturally Responsive Robotics Program" Education Sciences 15, no. 4: 514. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040514

APA StyleThompson, H. R., Caudle, L. A., Harper, F. K., Quinn, M. F., Avin, M. K., & The CRRAFT Partnership. (2025). Partnerships as Professional Learning: Early Childhood Teaching Assistants’ Role Development and Navigation of Challenges Within a Culturally Responsive Robotics Program. Education Sciences, 15(4), 514. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040514