Abstract

In the past two decades, there has been an increasing interest in integrating mindfulness practices as part of the school curriculum. The aim of this study was to examine the impact of a unique intervention program, specifically designed for the study, which integrated mindfulness exercises as an integral part of the science curriculum. The study involved 460 students aged 9–11 from six elementary schools. In each school, classes were randomly assigned to either an experimental group or a control group. In the experimental group, science lessons were taught using a contemplative instruction approach that incorporated mindfulness activities, including introspective inquiry, mental training, and meditation, focused on the specific content of each science class. In the control group, science lessons were taught as usual. Students filled in questionnaires and achievements were collected before, immediately after, and six months after the intervention. Students in the mindfulness group demonstrated significantly higher levels of mindfulness, motivation, and achievement in science compared to students in the control group, and the improvement was maintained 6 months later. The program used in this study can be relatively easily integrated into the elementary school curriculum as a whole and specifically in the science discipline.

1. Introduction

Mindfulness is defined as ‘the awareness that emerges through paying attention, on purpose, in the present moment, and non-judgmentally to the unfolding of experience moment by moment’ (Kabat-Zinn, 2003, p. 145). Mindfulness involves two components: one pertains to a mental state characterized by full attention to internal and external experiences and the other describes a unique approach characterized by openness to the current experience, allowing individuals to develop the capacity to stay with the experience and observe it objectively, subsequently alleviating suffering and cultivating qualities such as awareness, self-understanding, self-acceptance, compassion, and equanimity (Greco et al., 2008).

During mindfulness practice, individuals are encouraged to focus on an anchor to stay present. This deliberate process involves shifting attention from external stimuli to internal sensations, thoughts, and emotions, all approached with self-compassion and curiosity (Ergas, 2015; Gouda et al., 2016).

Various studies have found that mindfulness practices can lead to improvements in cognitive domains, including executive functioning (Flook et al., 2010), discursive thinking, working memory (Malinowski & Shalamanova, 2017; Pattrawadee, 2022), and attentional functions such as sustained attention, selective attention, and attentional control (Baena-Extremera et al., 2021; Davidson et al., 2012; Tarrasch, 2017).

Numerous studies suggest that mindfulness training offers emotional benefits (Hoge et al., 2021). Mindfulness interventions have helped individuals recognize and regulate automatic thoughts and behaviors linked to emotional difficulties (Chambers et al., 2009; Creswell, 2017). Furthermore, mindfulness practice has been found to be effective in enhancing psychological well-being (Burke, 2010; Carmody & Baer, 2008; Chen & Jordan, 2020) and reducing anxiety (Cynthia Agrita Putri Rizwari & Nurul Kemala, 2022; Hofmann et al., 2010).

1.1. Mindfulness in Education

In recent decades, there has been growing interest in integrating contemplative interventions into public education curricula (Roeser et al., 2022). A common element in these practices is the intentional and directed inward attention that facilitates experiential, intuitive, and embodied learning, which may not rely solely on conventional cognitive abilities typically emphasized in standard classroom settings (Ergas, 2016). Conducting such practices during regular instructional hours and within the classroom settings enhances their accessibility and effectiveness for students. This creates a comfortable environment in which they can fully engage in mindfulness activities (Felver et al., 2016).

Mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) are structured programs that use mindfulness practices to enhance psychological well-being, reduce stress, and improve focus. They are commonly applied in healthcare, education, and workplace settings. MBIs in educational settings are tailored to suit children (Sciutto et al., 2021) and do not require prior knowledge, cognitive abilities, advanced linguistic skills, or high physical demands (Gu et al., 2015). The adaptation of activities aims to create developmentally appropriate methods for practicing key aspects of mindfulness. These aspects include non-judgmental awareness of moment-to-moment experiences, attention monitoring, redirecting attention when it wanders, and non-reactive observations of thoughts and personal feelings. Children’s involvement and enjoyment of mindfulness activities vary significantly. While some students participate easily and enjoy themselves (Huppert & Johnson, 2016; Schonert-Reichl & Lawlor, 2010), others face barriers such as difficulty concentrating or feeling tired (D’Alessandro et al., 2022).

Curriculum-based interventions incorporating mindfulness introduce students to a new meta-pedagogical approach that reshapes the learning process by fostering self-awareness, present-moment focus, and emotional regulation. This approach helps students engage more deeply with their learning experiences, improving attention, resilience, and overall well-being. Prioritizing time in the curriculum for activities that focus students’ attention on their breath, thoughts, and feelings may have an impact on their understanding of the subject matter (Ergas, 2019). In Kabat-Zinn’s (2003) definition, two fundamental aspects of mindfulness in education are expressed and applied in various forms. The cognitive aspect is related to attention, concentration, emotional regulation, and self-reflection, while the affective aspect is related to cultivating positive and prosocial mental states, such as compassion, generosity, openness, and friendliness. Accordingly, mindfulness provides a foundation for academic learning while also supporting the development of socio-emotional skills, making it highly significant within the education system.

Mindfulness can be integrated into education in three different roles. The first role is mindfulness in education, which involves integrating adapted practices into the school culture. The second role is mindfulness as education, which involves applying mindfulness principles to the educational curriculum, such as focusing attention on the learning experience. This approach reflects the inherent value of the practice itself. The third role is mindfulness of education, which means using insights gained from mindfulness practice to critically reflect on and constructively analyze educational practices. From this perspective, directing attention and thought toward education becomes a subject of criticism aimed at achieving personal and social liberation (Ergas, 2019).

Research on the integration of meditative practices into educational frameworks and schools demonstrates positive outcomes (Ventura et al., 2023; Zenner et al., 2014). Studies indicate that educational interventions based on mindfulness have a significant influence among students on cognitive, behavioral, social, and emotional aspects underlying teaching, learning, and school life (J. L. Brown et al., 2023; Dunning et al., 2019; Schonert-Reichl & Lawlor, 2010; Semple et al., 2017). Mindfulness practices have been shown to aid in emotional regulation by reducing anxiety and strengthening students’ emotional resilience. This leads to improved mental well-being (Schonert-Reichl & Lawlor, 2010), greater adaptability, and lower levels of stress, pressure, and depression (Davidson et al., 2012; Kuyken et al., 2013; Semple et al., 2010). Through mindfulness practices, students develop the ability to focus and pay attention to meaningful occurrences in the classroom (Ojell et al., 2023; Semple et al., 2010), thereby enhancing their academic and behavioral performance in school (Verhaeghen, 2023; Weare, 2013). Improvements in cognitive abilities encompassed enhancements in executive functions (Flook et al., 2010; Mak et al., 2018), attentional control (Tarrasch, 2017), and academic improvements in various subjects, including mathematics and reading (Bakosh et al., 2018; Caballero et al., 2019; Mrazek et al., 2013). Furthermore, research shows that mindfulness practices promote the development of social skills and positive social orientation, which are reflected in behaviors such as respecting others and fostering prosocial attitudes like empathy, compassion, and ethical sensitivity. In addition, mindfulness practices enhance self-awareness, which involves monitoring one’s thoughts, actions, and emotions. Enhancing self-awareness and reflection on social issues, along with reducing behavioral disturbances, is crucial for students. This improvement positively affects learning processes and fosters ’deep learning’, characterized by intrinsic motivation and curiosity, which are key predictors of student achievement (Maynard et al., 2017; Zenner et al., 2014).

Along with these findings, some recent studies have indicated that the effects of mindfulness practices are inconsistent, showing no significant improvement in student performance across academic (Alomari, 2023; Wu, 2022), behavioral (Portele & Jansen, 2023), and emotional (Malboeuf-Hurtubise et al., 2024) domains.

1.2. Instructional Methods and Learning Programs

In recent years, a global trend of change has emerged, which involves incorporating various instructional methods based on the constructivist approach. The goal is to facilitate experiential learning where both teaching and learning occur through challenging experiences that engage learners cognitively, physically, socially, and emotionally (Kolb & Kolb, 2011; Weinberg et al., 2011). Different programs that incorporate mindfulness practices are implemented in schools worldwide (Mettler et al., 2023; Sciutto et al., 2021). These programs are designed for children and adolescents, involving educational staff and sometimes parents. Their objectives are to develop compassion, empathy, and patience; enhance student engagement; and improve the school climate, academic performance, and more (Albrecht et al., 2012). Additionally, there are other programs that integrate mindfulness activities within core subjects such as reading, language, mathematics, arts, sciences, and social sciences, alongside additional lessons such as physical education and music (Maynard et al., 2017). Many schools in England have introduced mindfulness exercises as part of their curriculum (Hemming & Hailwood, 2024). Hundreds of students in participating schools engaged in relaxation and breathing techniques as part of the mindfulness practice, aimed at regulating their emotions and fostering their mental well-being (Barr, 2019).

1.3. The Impact of Mindfulness on Academic Achievements

The introduction of mindfulness programs in schools has raised the need to examine the implications and effects of these programs on students’ academic achievements. Academic achievements and success are influenced by cognitive, behavioral, motivational, and personality factors, which sometimes outweigh academic skills (DiPerna & Elliott, 2002). Research indicates that age-appropriate mindfulness practices tailored to the student population are beneficial and have a positive impact on academic performance (Tamburrino & Levine, 2024). This impact is attributed to the fact that through mindfulness practices, students are ‘present in the moment’ and therefore less distracted. They are more focused and have self-control and personal well-being, which positively influence their academic performance (Indriaswuri et al., 2023). The improvement in academic performance as a result of mindfulness practices is reflected in enhanced mental abilities, memory, creativity, learning skills, and academic achievements (Caballero et al., 2019; Weare, 2013).

1.4. Mindfulness and Motivation

Motivation can be defined as a dynamic system of beliefs, emotions, and cognitive processes that influence and direct behavior. It shapes how individuals initiate, sustain, and regulate their actions, guiding their efforts toward achieving goals and responding to challenges (Martin, 2008; Wentzel, 1999). Motivation arises from commitment, emotional guilt, personal goals, or values and refers to behavioral processes characterized by initiative and persistence. Motivation plays a central role in academic success, promoting and maintaining academic achievements, emotional and behavioral adaptation to learning and school, classroom behavior, coping with difficulty and failure, and psychological well-being (Kaplan & Maehr, 1999; Mega et al., 2014; Schunk et al., 2014). Motivation can be classified along a continuum, ranging from a lack of motivation through controlled motivation, where the driving force is external, to autonomous motivation, where the driving force is internal. Self-Determination Theory refers to the ability to choose between behaviors that differentiate between intrinsic motivation, which develops from feelings of interest and excitement, and extrinsic motivation, which is driven by external pressures, reinforcements, or punishments. When individuals respond automatically and are unaware of their emotions and feelings, they may generate behaviors that are not based on self-determination (Deci & Ryan, 1985). Individuals with autonomous motivation, including intrinsic and integrated extrinsic motivation, experience a sense of self-determination in their behaviors and focus more on fulfilling their needs and adopted values (Ryan & Deci, 2002).

Mindfulness encompasses both attention and self-awareness, which may enable self-regulation of behavior, thereby facilitating self-directed or autonomous behaviors (K. W. Brown & Ryan, 2003). The ability to direct attention and be mindful of the internal and external experiences of the present moment through mindfulness practices highlights the close relationship between attention and self-awareness and provides a common foundation for linking attention to Self-Determination Theory. Self-directed attention accompanied by mindfulness can foster attentiveness to basic needs and values, increasing the likelihood that individuals align their behavior in a way that meets such needs. Conversely, it allows for detachment and distancing from emotions, thoughts, and behaviors to which individuals are accustomed, thus enabling new choices and adaptations to the situation (K. W. Brown et al., 2007; Levesque & Brown, 2007). According to Ryan et al. (2021), there may be individual differences in the propensity to act mindfully. An individual who is attentive is more likely to have autonomous motivation compared to someone who is less attentive, as attentive individuals are capable of being aware of and paying attention to the emotions that arise within them and accepting them (Ryan et al., 2021). They may be able to ‘look inward’ into their emotions more clearly and use the new information to guide behaviors. Therefore, attentive individuals tend to broaden their areas of interest, values, and adopted beliefs, leading to greater autonomous motivation (K. W. Brown et al., 2007). Attention allows individuals to develop heightened internal understanding while being sensitive to their internal needs and external reality, thereby enabling them to act from a high level of intrinsic and autonomous motivation and reduce the influence of externally controlled motivation (Ryan & Deci, 2008).

Building on this foundation, the present study aimed to assess the effectiveness of a “mindfulness as education” approach by integrating mindfulness practices into the science curriculum. This approach does not merely incorporate mindfulness as an auxiliary activity but embeds its principles within the learning process, emphasizing present-moment awareness, attentional control, and reflective engagement with scientific concepts. By fostering an educational environment where students actively cultivate mindfulness during science instruction, this study sought to examine its impact on cognitive engagement, intrinsic motivation, and long-term knowledge retention. Through structured mindfulness exercises interwoven with science lessons, students could develop enhanced attentional capacities and a deeper, more meaningful connection with scientific inquiry, while also gaining the benefits of “mindfulness in education”. This study explored whether this pedagogical integration can serve as a transformative educational tool, promoting both academic achievement and personal growth in learners. Despite the growing recognition of mindfulness as a valuable educational tool, research on its integration within subject-specific curricula, particularly in science education, remains scarce. While numerous studies have explored the benefits of mindfulness for general well-being and stress reduction, few have examined its direct impact on cognitive engagement, conceptual understanding, and learning outcomes in science classrooms. This gap underscores the need for empirical investigations into how mindfulness-based approaches can be meaningfully embedded within academic instruction. By addressing this limitation, the present study contributes to an emerging field of research, offering insights into the potential of mindfulness as an instructional strategy that enhances students’ attentional focus, curiosity, and conceptual retention. The findings may provide educators with evidence-based practices to foster both cognitive and emotional growth, thereby enriching science education with a holistic learning experience. Our research hypotheses were that integrated mindfulness exercises as a component of the curriculum in science education will (1) enhance students’ level of attention; (2) enhance students’ learning motivation: (a) mastery goal orientation, (b) performance-approach goal orientation, and (c) decrease performance-avoid goal orientation; (3) enhance students’ intrinsic motivation and decrease extrinsic motivation; and (4) increase motivation for science lessons and contribute to long-term knowledge retention.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

We initially recruited 512 students, but, after attrition, this study included 460 students from 4th and 5th grade classes aged 9–11 attending six elementary schools in central Israel. This study spanned two consecutive years, with different participants from the same schools taking part in each year. Five of the schools were of high socioeconomic status, while one was of low-to-medium socioeconomic status. The schools were selected for this study using convenience sampling. In total, 21 classes participated in this study, with 11 experimental classes (239 participants) and 10 control classes (221 participants). The gender distribution within each class in both the experimental and control groups showed similar proportions of boys and girls (49% and 51%, respectively).

2.2. Procedure

In each school, two classes were selected and allocated into two groups: one group served as the experimental group, while the other group served as the control group. The allocation of classes to the groups was conducted randomly. The same teacher taught both groups in each school, minimizing differences between the groups. In the experimental group, each of the ten science lessons began with a mindfulness meditation session. This was facilitated using a 5:36 min animated video titled ‘One Moment Meditation’ (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F6eFFCi12v8, accessed on 21 March 2017), which was translated into Hebrew for the purposes of this study, with permission from the creator, Martin Boroson. The video was used to guide students’ attention to the present moment and ensure consistent delivery across classrooms, even though the teachers had no formal mindfulness training. To support consistency and alignment with the intervention goals, teachers received structured and scripted lesson plans that detailed the mindfulness activities to be implemented. These included specific instructions, timing, and language prompts to facilitate student engagement and reflection during the science lessons. Following the meditation, mindfulness activities related to the lesson content were incorporated. These activities were included in one of the three weekly science lessons and involved individual, pair, or small group work. The goal was to foster a deep, reflective experience that encouraged students to share their personal thoughts and feelings at the end of each activity. All mindfulness activities were designed to align with the science curriculum and the eight study topics covered during the research period. The full intervention program included 47 lesson units (some of which extended across multiple lessons). From this set, each teacher selected 10 units that best matched their specific curriculum needs (for a detailed breakdown of the lesson units, see Table 1). These lessons incorporated mindfulness activities that focused on sensory experiences such as body awareness, bodily sensations, breath awareness, movement awareness, touch, auditory awareness, visual attention, and focused attention. Practices lasted between 5 and 10 min and were facilitated by the classroom teacher. At the end of each lesson, students were assigned a mindfulness homework task aimed at extending their observation of feelings and sensations beyond the classroom. Although teachers did not receive formal mindfulness training, the use of a fixed set of instructional materials and consistent delivery protocols was intended to minimize variation and enhance fidelity across classrooms.

Table 1.

Lesson units by study topic.

In contrast, the control group followed the standard science curriculum without any mindfulness activities. As an example, in a lesson on vertebrates and invertebrates, students were asked to cut a 2.5–3 cm diameter circle in the center of an A4 sheet and try to pass their fingers—or their whole hand—through it slowly, paying attention to hand sensations while keeping the paper intact. This activity was followed by a video of an octopus passing through a similarly sized hole (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=949eYdEz3Es&ab_channel=JamesWood, accessed on 21 March 2017). A class discussion then explored the differences between vertebrates and invertebrates, focusing on the structural factors affecting movement through tight spaces. As a follow-up homework activity, students were asked to observe their own feelings when navigating narrow spaces.

The effectiveness of incorporating mindfulness practices into science lessons was evaluated using students’ science grades, as well as questionnaires measuring their levels of mindfulness and motivation to learn. These assessments were conducted at three time points: before the intervention, immediately after its completion, and six months later. In addition, a science knowledge test covering the program’s content was administered at two time points: immediately after the intervention and at the six-month follow-up. Both the experimental and control groups completed all questionnaires and tests.

2.3. Measures

The reliabilities of the measures in the present study are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency reliabilities of the study variables as measured at pre-intervention, post-intervention, and follow-up.

Mindful Attention Awareness Scale (MAAS). This questionnaire, developed by K. W. Brown and Ryan (2003), consists of 15 items that assess levels of mindfulness. The response range for each item is on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (almost always) to 6 (almost never). Sample items include ‘I find it difficult to stay focused on what’s happening in the present’ and ‘I find myself preoccupied with the future or the past’. The internal consistency reliability of the questionnaire, as measured by Cronbach’s alpha, ranges from 0.80 to 0.87.

Patterns of Adaptive Learning Scales (PALS) (Midgley et al., 2000). The Hebrew version (Levy & Kaplan, 2003) consists of 14 items that assess achievement goals. The response range for each item is from 1 (not true) to 5 (very true). The questionnaire includes three subscales: Mastery Goal Orientation (PALS-MG), composed of 5 items (e.g., ‘I complete classroom tasks to learn as much as possible’; Performance-Approach Goal Orientation (PALS-AP), composed of 5 items (e.g., ‘One of my goals is to show others that I am good at my studies’; and Performance-Avoid Goal Orientation (PALS-AV), composed of 4 items (e.g., ‘It is important to me that my teachers do not think I know less than other students’. The internal consistency reliability, as measured by Cronbach’s alpha for the three subscales, is α = 0.86, 0.90, and 0.79, respectively.

The Self-Regulation Questionnaire—Academic (SRQ-A). Students rated their level of agreement or disagreement with statements describing various motivations for learning in school. The questionnaire is based on the scale developed by Ryan and Connell (1989) and translated by Katz et al. (2010, 2012). It consists of 11 items, with response options ranging from 1 (not true at all) to 5 (very true). Six of the responses reflect intrinsic motivation (autonomous motivation—SRQ-I), for example, ‘I study in school because it’s important to me’, while five responses reflect extrinsic motivation (controlled motivation—SRQ-E), for example, ‘I study in school so that my parents won’t be ashamed of me’. The internal reliabilities of the intrinsic and extrinsic motivation scales are 0.85 and 0.61, respectively (Lahav, 2013, in Hebrew).

Science Motivation Questionnaire (MOT). Students rated their level of agreement or disagreement with statements describing various motivations for learning in science lessons. The questionnaire was developed for the purpose of the current study. It consists of 5 items, with response options ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 4 (very true). For example, ‘I want to learn more things in the field of science’.

Science grades (GRs). Actual science grades were collected from the teachers.

Science Knowledge Test (KN). This questionnaire included questions collected from the tests and exams administered to students as part of the instructional program and covered the topics learned during that period. The questionnaire comprised 11 multiple-choice questions. One example is as follows: An octopus could easily pass through a small and narrow opening due to its: (a) exceptionally flexible tissue, (b) relatively flexible bones, or (c) lack of vertebrae.

2.4. Data Analyses

To assess the impact of the intervention on the study variables, a series of hierarchical linear model (HLM) analyses were performed, using the fixed effects of measurement time (pre/post/follow-up), group (experimental/control), gender (male/female), the interaction between measurement time and group, and the interaction between measurement time, group, and gender, and the random effects of participants and classrooms nested within schools. Significant interactions were followed by Bonferroni-corrected post hoc tests.

3. Results

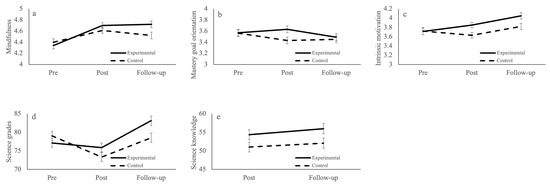

Means and standard errors of the study variables by group and time are presented in Table 3. Table 4 summarizes the effects obtained from the HLM analyses. The partial eta-squared effect sizes for the significant interactions ranged from 0.003 to 0.02. Reported mindfulness yielded a significant interaction between group and time. As can be seen in Figure 1a, Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons yielded a significant increase in both groups between the pre- and post-measures (p’s < 0.001); however, a significant group by time interaction (comparing only pre- and post-measures; F(1, 389) = 4.86, p = 0.028) demonstrated a larger effect in the intervention group. The increased mindfulness, however, was maintained among participants in the intervention group only, as the follow-up measure was significantly higher than the pre-measure among participants of the intervention group (p < 0.001), but not among controls (p = 0.168).

Table 3.

Means and standard errors (in parentheses) of study variables by group and time.

Table 4.

Effects of group, time, gender, group × time, and group × time × gender in HLM analyses of study variables.

Figure 1.

Means and standard errors by group and time of measurement for variables with significant outcomes: (a) MAAS; (b) PALS; (c) SRQ-I; (d) GRs; (e) KN.

For mastery goal orientation, no interaction between group and time was obtained. As can be seen in Figure 1b, a significant difference between the groups at post-test only was obtained (p = 0.019), but was not maintained at follow-up.

For performance-approach goal orientation, a significant main effect of time was obtained. Post-hoc analyses conducted to examine the source of the effect revealed a significant increase in performance-approach goal orientation from pre-intervention to post-intervention (p = 0.011) and between pre-intervention and follow-up (p < 0.001), without a significant difference between the post- and follow-up measures (p = 0.148). In addition, a significant main effect of gender was found, with higher avoidance goal scores among boys (M = 2.95; SE = 0.061) relative to girls (M = 2.77; SE = 0.059). For performance-avoid goal orientation, only a significant main effect of time was obtained. Post-hoc analyses indicated a significant decrease (p = 0.032) from pre- to post-intervention measures. Additionally, a significant decrease (p = 0.009) was observed between pre-intervention (M = 3.70; SE = 0.045) and follow-up (M = 3.54; SE = 0.049). No significant difference was found between post (M = 3.57; SE = 0.046) and follow-up (p = 1.00).

For intrinsic motivation, a trend for an interaction between group and time was obtained (p = 0.069). As can be seen in Figure 1c, Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons revealed a significant increase between pre- and follow-up measures in the intervention (p < 0.001) but not in the control group (p = 0.704). The two groups did not differ at baseline (p = 0.921); however, the intervention group showed higher intrinsic motivation at the post-measure (p = 0.015) and follow-up (p = 0.022). Extrinsic motivation yielded a significant main effect of time. A significant decrease (p = 0.007) was observed between the measurements before (M = 1.77; SE = 0.051) and after (M = 1.74; SE = 0.039) the intervention compared to follow-up (M = 1.61; SE = 0.039). In addition, a significant main effect of gender was obtained, with higher levels of extrinsic motivation among males (M = 1.87; SE = 0.045) compared to females (M = 1.55; SE = 0.045).

For science motivation, a three-way interaction between group, time, and gender was obtained. Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons revealed a significant increase between pre- and follow-up measures among boys in the intervention group (p = 0.016), but not in the control group (p = 0.24). In addition, a significant main effect of group was obtained.

For science grades, a significant interaction between group and time was obtained. As can be seen in Figure 1d, Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons revealed a significant increase at follow-up as compared to pre- and post-test (p’s < 0.001), but not between pre- and post-measure (p = 0.847), among participants in the experimental group. Among participants in the control group, a significant decrease in science grades was observed between pre- and post-measures (p < 0.001), followed by an increase that did not yield a significant difference between pre- and follow-up measures (p = 1). In addition, a significant main effect of time was obtained. Data from the science knowledge test were available for the post- and follow-up measures only. The analysis yielded a significant main effect of group (see Figure 1e).

4. Discussion

The aim of the present study was to examine the impact of an intervention program that integrated mindfulness activities into science lessons on cognitive and behavioral variables among fourth- and fifth-grade elementary school students. Our findings indicate that the gains obtained as a result of participating in the mindfulness program were maintained over time compared to the control group in terms of mindfulness abilities, intrinsic motivation, motivation for science lessons among boys, and science grades. These findings suggest the long-term positive influence of the intervention program.

This study adds to previous research based on a new meta-pedagogical approach that belongs to contemplative teaching focused on training mindfulness and focused attention in the ‘here and now’. Other studies have already shown that incorporating meditative practices into educational frameworks yields positive results (Ergas, 2019; Semple et al., 2017; Stapleton et al., 2024; Zenner et al., 2014). Thus, it appears that allocating resources beyond the traditional science curriculum significantly contributes to enhancing mindfulness, motivation for learning in general and in science in particular, and improving academic achievements. Allocating time in the curriculum for science instruction accompanied by experiential activities with a focus on emerging feelings and providing feedback on them in practice contributes to improving the functioning of the learner in the field of science. These findings provide empirical support for the argument made by Fortus and Touitou (2021) that motivation for learning and academic achievements, in general and in science in particular, is related to educational resource allocation in education as a whole and to the student individually. The finding that boys in the mindfulness intervention group showed increased science motivation, while girls did not, contrasts with existing research on gender differences in mindfulness outcomes (Kang et al., 2018). Future studies should explore this discrepancy.

Maintaining a stable level of motivation among participants in the mindfulness group throughout the implementation of the intervention program may indicate that the intervention program had a positive impact and served as a protective factor against a decline in motivation related to achievement goals (Meece et al., 2006). These findings support previous research that demonstrated the contribution of mindfulness to motivation, learning, and the broadening of interests through improved awareness and attention to emotions (K. W. Brown et al., 2007; Li et al., 2023; Ryan & Deci, 2008).

The increase in motivation for science lessons among students in the mindfulness group, compared to the pre-intervention measurement and in relation to students in the control group, may be attributed to the change in the contemplative instructional method used in these lessons. The science lessons in this study included experiential, diverse, and sensory activities, such as spatial movement, video watching, and sensory integration with some emotional elements. It is possible that mindfulness activities allowed students to experience the lessons in a more focused, attentive, deep, and engaging manner. However, possible mediating factors should be assessed in future studies.

Our findings align with previous studies showing that the learning and academic achievements of students are influenced by motivation and emotional factors (Mega et al., 2014; Schunk et al., 2014; Skinner et al., 2016). These improvements lead to an increase in self-efficacy and also assist in focusing cognitive efforts on learning (Ames, 1992; Anderman et al., 2002; Midgley et al., 2001). Additionally, studies indicate that teachers play a central and relevant role in students’ academic outcomes (Maulana et al., 2016). The teachers implemented the intervention program in the classrooms and taught the lesson content while integrating mindfulness activities and explicit learning materials. The significance of the teachers lay in their continuous support of the students throughout the school day, familiarizing themselves with their abilities, and successfully arousing interest and active involvement in learning. All of these factors most probably contributed to promoting the motivation of the study participants, leading to high academic achievements in science.

The effect of mindfulness practices on students’ academic achievements is inconsistent. While many studies have found a positive impact (Indriaswuri et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2022), others have not (Alomari, 2023; Wu, 2022). In the present study, students in the mindfulness group demonstrated better attitudes toward science, as reflected in their enhanced knowledge and mastery of the subject compared to the control group. Participation in mindfulness activities helped prevent the decline in science grades observed in the control group. Furthermore, the mindfulness group outperformed the control group in science test scores, with the gains remaining stable over time. These findings suggest that participation in the intervention program, tailored to the age and student population, contributed to the long-term preservation of knowledge.

4.1. Study Limitations

The teachers who implemented the program in the classrooms did not receive formal training for program delivery, except for detailed lesson plans in science incorporating mindfulness and brief oral explanations. Additionally, teachers did not practice mindfulness themselves nor did they deliver practice sessions to their students beforehand. These factors may have diminished the teachers’ confidence in the way they delivered the program in their classrooms, thus reducing its potential positive impact.

While detailed lesson plans and standardized materials were provided, the absence of formal training may have resulted in variability in how teachers interpreted and delivered the mindfulness components. This potential lack of implementation fidelity limits the ability to draw firm conclusions about the direct effects of the intervention. Future studies should consider incorporating structured training and ongoing support for teachers to enhance consistency and ensure the intervention is delivered as intended.

The intervention program was designed to span ten consecutive weeks to maintain the continuity of practice. However, in practice, the dynamics in schools did not allow for a ten-week sequence due to numerous class cancellations, such as field trips, teacher illnesses, and school activities. As a result, the implementation period of the intervention program exceeded the planned duration.

The research questionnaires were completed during a school day by the students in the context of a regular lesson while sitting alongside their peers, rather than in a neutral location. It is possible that this influenced their responses. Additionally, not all children expressed willingness to collaborate and invest effort in completing the questionnaires. Another limitation is the self-report nature of mindfulness questionnaires. Future studies could incorporate more ecological measures.

Another potential limitation is the influence of the program on teachers’ approaches and instructional methods, which they employed while teaching both groups. It can be assumed that due to their exposure to and familiarity with mindfulness, their approach became more inclusive and attentive to students. Additionally, it is possible that elements of mindfulness were incorporated into other lessons, including those delivered to the control group. However, such leakage would only reduce the differences between the experimental and control groups.

4.2. Recommendations for Further Research

Future studies should encompass the need for teacher training and implement an alternative program for the control group. In addition, the duration of the intervention program should be extended throughout the school week and year, and be integrated into additional subjects to become part of the school curriculum. Accordingly, mindfulness principles could become a way of life and have a positive influence on academic, social, and emotional aspects of students and teachers, as well as the culture and climate of schools. Since the teachers who deliver the program play a significant role in its success, it is also recommended that more in-depth training be conducted for teachers, including theoretical and practical aspects of mindfulness. Future studies are encouraged to use more reliable measures, as the Hebrew version of the performance-avoid goal orientation used in this study showed relatively low values across the three time points. Finally, future research could examine whether MBIs differentially impact students with varying baseline levels of attentional control or emotional regulation.

5. Conclusions

One of the advantages of integrating mindfulness activities into the school curriculum, as supported by the current research, is that activities based on the reflective pedagogy approach are easy to implement and apply, requiring minimal time allocation. Moreover, research findings show that even a brief experience of two or three minutes, week after week, has the potential to increase student engagement in the lesson.

The findings of this study provide meaningful evidence for the long-term benefits of mindfulness-based practices when integrated into formal education. Specifically, improvements in students’ mindfulness abilities and motivation—particularly among boys—as well as their academic performance in science suggest that even simple and low-resource interventions can yield significant cognitive and emotional benefits. The incorporation of experiential and sensory activities within science instruction appears to offer a promising pedagogical approach that enhances not only content mastery but also attentional and emotional engagement. Importantly, this study demonstrates that classroom teachers, even without formal mindfulness training, can successfully facilitate mindfulness-based practices when provided with structured guidance and lesson plans. This reinforces the practicality and scalability of integrating such interventions in a variety of educational contexts.

However, for these benefits to be sustained and maximized, future implementations should consider systemic support, including professional development for teachers, consistent scheduling, and integration across subjects. Additionally, the gender-related differences observed in motivational outcomes highlight the need for further exploration into how mindfulness interventions may affect subgroups differently.

In conclusion, the present study supports the inclusion of mindfulness practices as a valuable complement to traditional teaching methods. By cultivating awareness, emotional regulation, and motivation, mindfulness contributes not only to academic achievement but also to the holistic development of students. Expanding this approach to more classrooms and diversifying its application across subjects and age groups may further enhance its positive impact on students’ learning experiences and well-being.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.S.I. and R.T.; methodology, O.S.I. and R.T.; software, R.T.; validation, R.T.; formal analysis, R.T.; investigation, O.S.I.; resources, O.S.I. and R.T.; data curation, O.S.I. and R.T.; writing—original draft preparation, O.S.I. and R.T.; writing—review and editing, R.T.; visualization, R.T.; supervision, R.T.; project administration, O.S.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Tel Aviv University and the Chief Scientist of the Israeli Ministry of Education (protocol codes 9058-504 and 9194-555, 5 May 2016).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in Mendeley data at DOI 10.17632/sjdfr9c3mr.1.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| MAAS | Mindfulness (original scale reversed) |

| PALS-MG | PALS: mastery goal orientation |

| PALS-AP | PALS: performance-approach goal orientation |

| PALS-AV | PALS: performance-avoid goal orientation |

| SRQ-I | SRQ-A: intrinsic motivation |

| SRQ-E | SRQ-A: extrinsic motivation |

| MOT | Science motivation |

| GRs | Science grades |

| KN | Science knowledge test |

References

- Albrecht, N. J., Albrecht, P. M., & Cohen, M. (2012). Mindfully teaching in the classroom: A literature review. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 37(12), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alomari, H. (2023). Mindfulness and its relationship to academic achievement among university students. Frontiers in Education, 8, 1179584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ames, C. (1992). Classrooms: Goals, structures, and student motivation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 84(3), 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderman, L. H., Patrick, H., Hruda, L. Z., & Linnenbrink, E. A. (2002). Observing classroom goal structures to clarify and expand goal theory. In C. Midgley (Ed.), Goals, goal structures, and patterns of adaptive learning (pp. 243–278). Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Baena-Extremera, A., Ortiz-Camacho, M. D. M., Marfil-Sánchez, A. M., & Granero-Gallegos, A. (2021). Improvement of attention and stress levels in students through a Mindfulness intervention program. Revista de Psicodidáctica (English Edition), 26(2), 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakosh, L. S., Mortlock, J. M. T., Querstret, D., & Morison, L. (2018). Audio-guided mindfulness training in schools and its effect on academic attainment: Contributing to theory and practice. Learning and Instruction, 58, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barr, S. (2019). Children to be taught mindfulness as mental helth trails launch in 370 english schools. Available online: https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/health-and-families/mental-health-schools-mindfulness-relaxation-breathing-children-pupils-a8761801.html (accessed on 3 October 2023).

- Brown, J. L., Jennings, P. A., Rasheed, D. S., Cham, H., Doyle, S. L., Frank, J. L., Davis, R., & Greenberg, M. T. (2023). Direct and moderating impacts of the CARE mindfulness-based professional learning program for teachers on children’s academic and social-emotional outcomes. Applied Developmental Science, 29(1), 14–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K. W., Ryan, R. M., & Creswell, J. D. (2007). Mindfulness: Theoretical foundations and evidence for its salutary effects. Psychological Inquiry, 18(4), 211–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, C. A. (2010). Mindfulness-based approaches with children and adolescents: A preliminary review of current research in an emergent field. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19(2), 133–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, C., Scherer, E., West, M. R., Mrazek, M. D., Gabrieli, C. F. O., & Gabrieli, J. D. E. (2019). Greater mindfulness is associated with better academic achievement in middle school. Mind, Brain, and Education, 13(3), 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmody, J., & Baer, R. A. (2008). Relationships between mindfulness practice and levels of mindfulness, medical and psychological symptoms and well-being in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 31(1), 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, R., Gullone, E., & Allen, N. B. (2009). Mindful emotion regulation: An integrative review. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(6), 560–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, S., & Jordan, C. H. (2020). Incorporating ethics Into brief mindfulness practice: Effects on well-being and prosocial behavior. Mindfulness, 11(1), 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. D. (2017). Mindfulness interventions. Annual Review of Psychology, 6, 491–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cynthia Agrita Putri Rizwari, M., & Nurul Kemala, C. (2022). Mindfulness based intervention to overcome anxiety in adolescents. ANALITIKA, 14(2), 154–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Alessandro, A. M., Butterfield, K. M., Hanceroglu, L., & Roberts, K. P. (2022). Listen to the children: Elementary school students’ perspectives on a mindfulness intervention. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 31(8), 2108–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, R. J., Dunne, J., Eccles, J. S., Engle, A., Greenberg, M., Jennings, P., Jha, A. P., Jinpa, T., Lantieri, L., Meyer, D., Roeser, R. W., & Vago, D. (2012). Contemplative practices and mental training: Prospects for American education. Child Development Perspectives, 6(2), 146–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. Plenum. [Google Scholar]

- DiPerna, J. C., & Elliott, S. N. (2002). Promoting academic enablers to improve student achievement: An introduction to the mini-series. School Psychology Review, 31(3), 293–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, D. L., Griffiths, K., Kuyken, W., Crane, C., Foulkes, L., Parker, J., & Dalgleish, T. (2019). Research review: The effects of mindfulness-based interventions on cognition and mental health in children and adolescents—A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 60(3), 244–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergas, O. (2015). The deeper teaching of mindfulness “interventions” as a reconstruction of “education”. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 49(2), 203–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergas, O. (2016). Educating the wandering mind: Pedagogical mechanisms of mindfulness for a curricular blind spot. Journal of Transformative Education, 14(2), 98–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergas, O. (2019). Mindfulness in, as and of education: Three roles of mindfulness in education. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 53(2), 340–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felver, J. C., Celis-de Hoyos, C. E., Tezanos, K., & Singh, N. N. (2016). A systematic review of mindfulness-based interventions for youth in school settings. Mindfulness, 7(1), 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flook, L., Smalley, S. L., Kitil, M. J., Galla, B. M., Kaiser-Greenland, S., Locke, J., Ishijima, E., & Kasari, C. (2010). Effects of mindful awareness practices on executive functions in elementary school children. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 26(1), 70–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortus, D., & Touitou, I. (2021). Changes to students’ motivation to learn science. Disciplinary and Interdisciplinary Science Education Research, 3(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouda, S., Luong, M. T., Schmidt, S., & Bauer, J. (2016). Students and teachers benefit from mindfulness-based stress reduction in a school-embedded pilot study. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Greco, L. A., Lambert, W., & Baer, R. A. (2008). Psychological inflexibility in childhood and adolescence: Development and evaluation of the Avoidance and Fusion Questionnaire for Youth. Psychological Assessment, 20(2), 93–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, J., Strauss, C., Bond, R., & Cavanagh, K. (2015). How do mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and mindfulness-based stress reduction improve mental health and wellbeing? A systematic review and meta-analysis of mediation studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 37, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemming, P. J., & Hailwood, E. (2024). Mindfulness in schools: Issues of equality and diversity. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 45(5), 675–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, S. G., Sawyer, A. T., Witt, A. A., & Oh, D. (2010). The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: A meta-analytic review. Journal Consulting Clinical Psychology, 78(2), 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoge, E. A., Acabchuk, R. L., Kimmel, H., Moitra, E., Britton, W. B., Dumais, T., Ferrer, R. A., Lazar, S. W., Vago, D., Lipsky, J., Schuman-Olivier, Z., Cheaito, A., Sager, L., Peters, S., Rahrig, H., Acero, P., Scharf, J., Loucks, E. B., & Fulwiler, C. (2021). Emotion-related constructs engaged by mindfulness-based interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mindfulness, 12(5), 1041–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huppert, F. A., & Johnson, D. M. (2016). A controlled trial of mindfulness training in schools: The importance of practice for an impact on well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 5(4), 264–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Indriaswuri, R., Gading, I. K., Suranata, K., & Suarni, N. K. (2023). Mindfulness and academic performance: A literature review. Migration Letters, 20(9), 341–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Y., Rahrig, H., Eichel, K., Niles, H. F., Rocha, T., Lepp, N. E., Gold, J., & Britton, W. B. (2018). Gender differences in response to a school-based mindfulness training intervention for early adolescents. Journal of School Psychology, 68, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, A., & Maehr, M. L. (1999). Achievement goals and student well-being. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 24(2), 330–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, I., Buzukashvili, T., & Feingold, L. (2012). Homework stress: Construct validation of a measure. The Journal of Experimental Education, 80(4), 405–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, I., Kaplan, A., & Gueta, G. (2010). Students’ needs, teachers’ support, and motivation for doing homework: A cross-sectional study. The Journal of Experimental Education, 78(2), 246–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, A. Y., & Kolb, D. A. (2011). Experiential learning theory: A dynamic, holistic approach to management learning, education and development. In S. J. Armstrong, & C. V. Fukami (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of management learning, education and development (pp. 42–68). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Kuyken, W., Weare, K., Ukoumunne, O. C., Vicary, R., Motton, N., Burnett, R., Cullen, C., Hennelly, S., & Huppert, F. A. (2013). Effectiveness of the mindfulness in schools programme: Non-randomised controlled feasibility study. British Journal of Psychiatry, 203(2), 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahav, Y. (2013). In the eye of the beholder–gender differences in students’ perceptions of their teachers [Master’s thesis, Department of Education, Ben-Gurion University of the Negev]. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Levesque, C., & Brown, K. W. (2007). Mindfulness as a moderator of the effect of implicit motivational self-concept on day-to-day behavioral motivation. Motivation and Emotion, 31(4), 284–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, I., & Kaplan, A. (2003, April 13–16). Achievement goals and young adolescents? Prefernces for peers as cooperation partners: A longitudinal study. Poster Session Presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Chicago, IL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L., Meng, X., Hu, W., Geng, J., Cheng, T., Luo, J., Hu, M., Li, H., Wang, Y., & Wang, Y. (2023). A meta-analysis of the association between mindfulness and motivation. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1159902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Liu, Y., & Wang, C. (2022, December 24–26). The effect of mindfulness meditation on academic performance of students. 2021 International Conference on Public Art and Human Development (ICPAHD 2021), Kunming, China. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mak, C., Whittingham, K., Cunnington, R., & Boyd, R. N. (2018). Efficacy of mindfulness-based interventions for attention and executive function in children and adolescents—A systematic review. Mindfulness, 9(1), 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malboeuf-Hurtubise, C., Taylor, G., Lambert, D., Paradis, P.-O., Léger-Goodes, T., Mageau, G. A., Labbé, G., Smith, J., & Joussemet, M. (2024). Impact of a mindfulness-based intervention on well-being and mental health of elementary school children: Results from a randomized cluster trial. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 15894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinowski, P., & Shalamanova, L. (2017). Meditation and cognitive ageing: The role of mindfulness meditation in building cognitive reserve. Journal of Cognitive Enhancement, 1(2), 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A. J. (2008). Enhancing student motivation and engagement: The effects of a multidimensional intervention. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 33(2), 239–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maulana, R., Opdenakker, M.-C., & Bosker, R. (2016). Teachers’ instructional behaviors as important predictors of academic motivation: Changes and links across the school year. Learning and Individual Differences, 50, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard, B. R., Solis, M. R., Miller, V. L., & Brendel, K. E. (2017). Mindfulness-based interventions for improving cognition, academic achievement, behavior and socio-emotional functioning of primary and secondary students. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 13(1), 1–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meece, J. L., Anderman, E. M., & Anderman, L. H. (2006). Classroom goal structure, student motivation, and academic achievement. Annual Review of Psychology, 57, 487–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mega, C., Ronconi, L., & De Beni, R. (2014). What makes a good student? How emotions, self-regulated learning, and motivation contribute to academic achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 106(1), 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mettler, J., Khoury, B., Zito, S., Sadowski, I., & Heath, N. L. (2023). Mindfulness-based programs and school adjustment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of School Psychology, 97, 43–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midgley, C., Kaplan, A., & Middleton, M. (2001). Performance-approach goals: Good for what, for whom, under what circumstances, and at what cost? Journal of Educational Psychology, 93(1), 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Midgley, C., Maehr, M. L., Hruda, L. Z., Anderman, E., Anderman, L., Freeman, K. E., Gheen, M., Kaplan, A., Kumar, R., Middleton, M. J., Nelson, J., Roeser, R., & Urdan, T. (2000). Manual for the patterns of adaptive learning scales. University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mrazek, M. D., Franklin, M. S., Phillips, D. T., Baird, B., & Schooler, J. W. (2013). Mindfulness training improves working memory capacity and GRE performance while reducing mind wandering. Psychological Science, 24(5), 776–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ojell, H., Palohuhta, M., & Ferreira, J. M. (2023). A qualitative microanalysis of the immediate behavioural effects of mindfulness practices on students’ self-regulation and attention. Trends in Psychology, 31(4), 641–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattrawadee, M. (2022). Increasing attention and working memory in elementary students using mindfulness training programs. FWU Journal of Social Sciences, 16, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portele, C., & Jansen, P. (2023). The effects of a mindfulness-based training in an elementary school in Germany. Mindfulness, 14(4), 830–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeser, R. W., Galla, B., & Baelen, R. N. (2022). Mindfulness in schools: Evidence on the impacts of school-based mindfulness programs on student outcomes in P–12 educational settings. Available online: https://prevention.psu.edu/sel/issue-briefs/mindfulness-in-schools-evidence-on-the-impacts-of-school-based-mindfulness-programs-on-student-outcomes-in-p-12-educational-settings/ (accessed on 3 October 2023). [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Connell, J. P. (1989). Perceived locus of causality and internalization: Examining reasons for acting in two domains. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(5), 749–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2002). An overview of self-determination theory: An organismic-dialectical perspective. In E. L. Deci, & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of self-determination research (pp. 3–33). The University of Rochester Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2008). Self-determination theory and the role of basic psychological needs in personality and the organization of behavior. In O. P. John, R. W. Robins, & L. A. Pervin (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (3rd ed., pp. 654–678). The Guilford Press. Available online: http://psycnet.apa.org/psycinfo/2008-11667-026 (accessed on 3 October 2023).

- Ryan, R. M., Donald, J. N., & Bradshaw, E. L. (2021). Mindfulness and motivation: A process view using self-determination theory. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 30(4), 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schonert-Reichl, K. A., & Lawlor, M. S. (2010). The effects of a mindfulness-based education program on pre- and early adolescents’ well-being and social and emotional competence. Mindfulness, 1(3), 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, D. H., Meece, J. L., & Pintrich, P. R. (2014). Motivation in education: Theory, research, and applications (4th ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Sciutto, M. J., Veres, D. A., Marinstein, T. L., Bailey, B. F., & Cehelyk, S. K. (2021). Effects of a school-based mindfulness program for young children. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 30(6), 1516–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semple, R. J., Droutman, V., & Reid, B. A. (2017). Mindfulness goes to school: Things learned (so far) from research and real-world experiences. Psychology in the Schools, 54(1), 29–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semple, R. J., Lee, J., Rosa, D., & Miller, L. (2010). A randomized trial of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for children: Promoting mindful attention to enhance social-emotional resiliency in children. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19(2), 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, E. A., Pitzer, J. R., & Steele, J. S. (2016). Can student engagement serve as a motivational resource for academic coping, persistence, and learning during late elementary and early middle school? Developmental Psychology, 52(12), 2099–2117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stapleton, P., Dispenza, J., Douglas, A., Dao, V., Kewin, S., Le Sech, K., & Vasudevan, A. (2024). “Let’s keep calm and breathe”—A mindfulness meditation program in school and its effects on children’s behavior and emotional awareness: An Australian pilot study. Psychology in the Schools, 61(9), 3679–3698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamburrino, M., & Levine, E. (2024). Mindfulness matters. Journal of Organizational Psychology, 24(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarrasch, R. (2017). Mindful schooling: Better attention regulation among elementary school children who practice mindfulness as part of their school policy. Journal of Cognitive Enhancement, 1(2), 84–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ventura, A., Kissam, B., Chrestensen, K., Tfirn, I., Brailsford, J., & Dale, L. P. (2023). Implementation of a whole-school mindfulness curriculum in an urban elementary school: Tier 1 through tier 3. OBM Integrative and Complementary Medicine, 8(2), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhaeghen, P. (2023). Mindfulness and academic performance meta-analyses on interventions and correlations. Mindfulness, 14(6), 1305–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weare, K. (2013). Developing mindfulness with children and young people: A review of the evidence and policy context. Journal of Children’s Services, 8(2), 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, A. E., Basile, C. G., & Albright, L. (2011). The effect of an experiential learning program on middle school students. RMLE Online: Research in Middle Level Education, 35(3), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wentzel, K. R. (1999). Social-motivational processes and interpersonal relationships: Implications for understanding motivation at school. Journal of Educational Psychology, 91(1), 76–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B. (2022). Analysis of the relationship between mindfulness, personality, and academic performance. BCP Education & Psychology, 7, 423–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zenner, C., Herrnleben-Kurz, S., & Walach, H. (2014). Mindfulness-based interventions in schools—A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).