1. Introduction

The screening and surveillance of early infant development to identify developmental problems play a crucial role in supporting the well-being of children. These tasks are the responsibility of healthcare professionals, including psychologists, as an integral part of the medical team (

Drotar et al., 2008). Thus, psychology students must develop a strong understanding of infant development and monitoring as early detection and intervention are essential in addressing developmental concerns. Psychologists who specialize in infant care are key in assessing, intervening with, and conducting research on infants who have developmental disabilities, as well as supporting their families. Despite this, research has highlighted significant gaps in psychologists’ knowledge and practice regarding the monitoring of child development, emphasizing the need for improved training. Studies have shown deficiencies in education and practice related to developmental surveillance (

Chödrön et al., 2021;

Zeppone et al., 2012). Psychology education programs should incorporate principles of infant and early childhood developmental healthcare, including the understanding of milestones and red flags to better equip students in this essential field (

Osofsky & Lieberman, 2011). Additionally, undergraduate Thai psychology students expect skill development in their degree to align with the competencies outlined by the American Psychological Association (APA). It highlights the multifaceted nature of psychology education, from infant development to curriculum or intervention design for children and their parents, emphasizing the importance of practical developmental surveillance skills and adherence to professional guidelines in preparing students for future careers or further specialized psychology education (

Lertgrai & Rhein, 2024).

Conventional methods of teaching infant developmental psychology have been criticized for being teacher-centered and lacking active student involvement. Alternative approaches, such as anchored instruction using video-based cases, have shown promise in enhancing students’ learning and motivation (

Gunbas & Eger Aydogmus, 2022). Small-group observation of infant assessments has also been effective in teaching about child development, as already applied in pediatric and nursing education (

Bell, 2017;

Elicker et al., 2014). However, expanding its use across all psychology programs presents various challenges. Direct in-person observation of infants may be more suitable for institutions with medical schools or may have limitations due to the increased costs associated with site visits. With the growing number of students, coordinating conventional, in-person observation sessions has become increasingly difficult. Additionally, alternative methods, such as closed-circuit television, now encounter challenges related to children’s data privacy protection (

Birnhack et al., 2018). Thus, previous studies suggested that integrating active learning approaches, such as the use of educational games into psychology education, may enhance students’ understanding and improve the overall effectiveness of learning (

Connolly et al., 2012;

Saracho, 2023;

Subhash & Cudney, 2018).

Integrating creative methods such as anchored instruction using video-based cases, small-group infant assessments, and educational games into psychology education can enhance student engagement and foster a deeper understanding of infant development. These methods also address gaps in developmental surveillance training by educating professionals like psychologists, pediatricians, and other healthcare providers on monitoring and assessing the developmental progress of infants and toddlers. It could identify early signs of developmental delays or disorders so that appropriate interventions can be provided as early as possible before screening and delayed diagnosis steps. It ultimately ensures that future psychologists are well-equipped with both theoretical knowledge and practical skills necessary for early detection, intervention, and research in child development while overcoming challenges associated with traditional observation methods and ethical concerns related to personal data protection.

1.1. Designing Board Games for Developmental Psychology

Among educators, board games have increasingly been recognized as valuable educational and developmental tools for learners of all ages (

Murillo-Zamorano et al., 2021). In psychology courses, creating games for university students can build ideas by developing interactive prototypes, effectively linking imaginative ideas with practical implementation (

Corral et al., 2015). For psychology students as adult learners, board games are effective for developing skills and enhancing competencies, consistent with the principles of adult learning. Ultimately, board games provide an engaging, enjoyable, and effective way to facilitate learning and skill development across diverse educational fields (

Gonzalo-Iglesia et al., 2018;

Mangundjaya & Wicaksana, 2022), for example, in fields of psychology where brain function and intelligence are taught (

Zielinski, 2019), when teaching theoretical frameworks in counseling (

Armstrong, 2021), and when learning about the history of psychology (

Abramson et al., 2009). However, a significant gap exists in the development and validation of educational board games for developmental psychology, particularly for psychology, medical, and nursing students, as they have yet to be widely implemented or rigorously studied through formal research (

Abdulmajed et al., 2015). Developmental psychology has generated a vast amount of theory and research on the physical, cognitive, social, and emotional growth of children. However, this extensive body of knowledge has yet to be widely utilized by game developers creating content for learners (

Revelle, 2013).

Although board games hold great potential as educational tools, there is a need for further research to fully integrate developmental psychology theory into their design and practical application. Studies have shown that board games enhance memory retention and support the application of various psychology-related learned concepts; however, despite the vast insights provided by developmental psychology, there has been limited application of educational game design (

Revelle, 2013). Several studies have also highlighted the difficulty of determining the optimal balance of using board games in combination with conventional teaching methods for those learning about psychology-related issues. Both methods demonstrated comparable results in terms of long-term retention of knowledge (

Limniou & Mansfield, 2018). Moreover, a recent study found no significant difference in learning outcomes between board games and quizzes (

Whitt & Haselgrove, 2023). However, how to effectively use board games still needs further research and exploration regarding the target knowledge for psychology students. Against this background, this study used the ensemble ADDIE Model concept, following the work of

Ranuharja et al. (

2021) and

Zulkifli et al. (

2023), to make a creative series of board games. These games were then applied to enhance the understanding of infant developmental milestones and surveillance among psychology students.

1.2. A Brief Overview of Infant Developmental Milestones and Surveillance with Reference to the Developmental Surveillance and Promotion Manual (DSPM)

The term “developmental milestones” refers to age-specific abilities that infants and children acquire in relation to the main motor, cognitive, and social-emotional domains across the age ranges [for details, see the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s revised checklists in (

Zubler & Whitaker, 2022)]. Motor skills follow a predictable pattern, while social-emotional development starts with caregiver bonding and progresses to emotional regulation. Healthcare providers should regularly monitor these milestones during health visits to ensure timely progress (

Thomasgard & Metz, 2004). However, previous studies found that many families and caregivers possess only moderate knowledge of these milestones, particularly in infant development, emphasizing the need for better help to identify delays at an early stage, enabling timely interventions (

Sheldrick et al., 2019;

Zubler & Whitaker, 2022).

Additionally, developmental surveillance is an ongoing process that monitors child development to identify potential delays at an early stage. In Thailand, the national developmental screening program has the goal of the early identification of developmental disorders and promoting early stimulation of child development from infancy up to 6 years old by utilizing the Developmental Surveillance and Promotion Manual (DSPM) with five developmental domains, namely gross motor (GM), fine motor (FM), expressive language (EL), receptive language (RL), and personal and social (PS) aspects (

http://thaichilddevelopment.com; accessed on: 20 January 2024). The DSPM guidelines can also be used to assess a child’s progress across each developmental domain or early signs of developmental delays or disorders aligned with their developmental age. The evaluator receives assessments based on their performance in each domain, providing parents, healthcare workers or educators with valuable insights into developmental areas that may need further stimulation or improvement. While the rates of successful surveillance and screening have increased over the last decade, a lack of understanding and poor follow-up attendance remain challenges for routine check-ups (

Morrison et al., 2018). Therefore, as primary healthcare providers, psychologists should clearly understand the screening process, exercise guidelines, and instructions according to the DSPM, irrespective of whether they work at subdistrict health-promoting hospitals or at clinics of local, provincial, or university hospitals.

2. The Present Study

To enhance surveillance practices, evidence-informed milestones have been developed and revised, focusing on achievements that most children (≥75%) reach by specific ages. Moreover, the milestone checklists were recently revised because families and healthcare professionals indicated the need for improvements to better support developmental surveillance. These reviews suggest a need for improved awareness and consistent information about developmental milestones for university students studying psychology to support future optimal child development outcomes and surveillance (

Wilkinson et al., 2019;

Zubler & Whitaker, 2022).

This study employs a creative method by integrating board games as an interactive learning tool to foster a more engaging and innovative approach to developmental surveillance education for early-stage psychology students. It hypothesizes that the time effect of these games enhances students’ understanding of infant development and surveillance according to DSPM, while also assessing the treatment effect of board games compared to conventional teaching methods, ultimately improving awareness, consistency of information, and active engagement in psychology students to better support future child development outcomes. Therefore, this study examined and hypothesized the time effect of board games on students’ understanding of infant development and surveillance and the treatment effect of playing a series of board games for the experimental group while offering a comparison control group conventional teaching methods. This study sought to answer the following research questions: (1) What are the effects of a series of board games on psychology students’ understanding of infant development and surveillance over time? (2) What are the effects of conventional teaching methods on psychology students’ understanding of infant development and surveillance? (3) What are the psychology students’ experiences of playing the series of board games?

3. Method

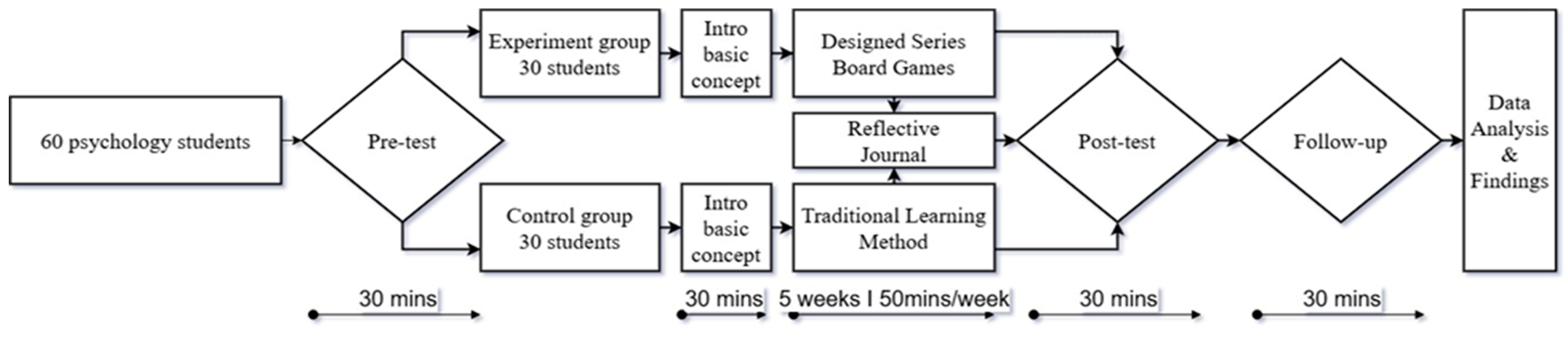

A convergent mixed-method approach was applied in this study. The experimental study was conducted using a randomized matched control-group pretest/posttest design, which included a follow-up phase. The variables of pretest score and gender were matched between the groups (

Stuart & Rubin, 2008). To obtain a comprehensive understanding of the learning experiences, the students were asked to fill in a journal on their reflections to complement the quantitative findings, describing the effectiveness and perceptions of the series of board games.

3.1. Participants

The participants in this study were 60 psychology students enrolled on second- and third-year courses at a large public university in Thailand. Following the experimental design using matched group assignment, 30 students were allocated to the control group (9 males, 21 females) and the other 30 to the experimental group (9 males, 21 females). A Chi-squared test showed no significant difference between these two groups when classified by gender, number of development-related courses being taken, and Grade Point Average (GPA), as shown in

Table 1.

3.2. Experimental Tools

The experimental group played a series of board games. In these games, they adopted and learned about revised infant developmental milestones (aged 0–2 years old) according to the recommendation of the CDC’s Revised Developmental Milestone Checklists (accessed at

https://www.cdc.gov/ActEarly/Materials; accessed on: 26 January 2024) and to ensure coverage of the five developmental domains of the DSPM concepts. The board games were as follows: Board Game 1 (GM covered):

Let’s move together! (infants and GM development: the essence of movement), Board Game 2 (FM covered):

Help me catch it! (infants and FM development: the key for catching), Board Game 3 (PS covered):

Come closer and win my heart! (infants and socioemotional development: the foundation of bonding), Board Game 4 (EL & RL covered):

Let’s understand my language! (language and comprehension: predictors of infant intelligence), and Board Game 5 (DSPM surveillance guidelines covered):

Keep an eye on me! (monitoring infant development: a critical focus area). The members of the group played each game in line with their assigned role and the rules of the game in groups of approximately 5–6 people. The students in each group were not required to compete to win the game but instead needed to work collaboratively to complete it. Each student was allocated a role in advance and took on different roles when playing each game three to four times within 50 minutes. This strategy involved methods for assigning students to participate in scaffolding activities within the game, incorporating additional knowledge from different roles in the game. Descriptions of the games are presented in

Table 2.

The ADDIE Model, consisting of five steps (i.e., analysis, design, development, implementation, and evaluation), was employed to develop a learning model using board games (

Trust & Pektas, 2018), along with the creation of storyboards for the 5 board games. During the analysis phase, learning needs, objectives, and the target audience were identified to ensure the games addressed key developmental domains through expert consultation, senior students’ feedback, and iterative design. The design phase involved structuring the card game mechanics and content through mainstream games with interaction between peers. A mnemonic device (such as rhymes, visual images, or acronyms) was partially applied as a helping tool for students to receive information during the card games. They were adapted for their engaging mechanics to known board games as an exemplary recommendation from the studies of

Nordin and Omar (

2022) and

Revelle (

2013). Game construction involved prototype development, pilot testing, and refinement informed by the literature and expert insights for improving the quality of the games. The outcomes of the design of these games included dimensions, visuals, colors, text, and gameplay. The quality of the developed model, comprising five board games, was then assessed by three experts in psychology and two experts in board game development. The assessment focused on content validity using a 5-point Likert-type scale, the variance of which was found to be appropriate (M = 4.40, SD = 0.03). Notably, the control and experimental groups used different learning strategies. A self-paced game learning approach was applied in the experimental group, while a textbook on infant developmental milestones/surveillance and PowerPoint presentations were provided with conventional teaching but no activities in the control group.

3.3. Measuring Tools

In this study, pretests and posttests were administered to assess the students’ understanding of infant developmental milestones and surveillance. The tests covered four developmental milestone concepts and one screening and surveillance concept, adopting the concepts from DSPM. The test pool of 80 items, originally developed in the areas of infants’ GM development, FM development, socio-emotional development, receptive and expressive language, and infant surveillance (aged 0–24 months), was validated by three learning and psychology experts using an Index of Item-Objective Congruence (IOC). In this study, all experts confirmed the accuracy of items, ensuring alignment with infant developmental milestones and the adoption of DSPM screening and surveillance guidelines.

The difficulty index (p) was accepted, and the Kuder–Richardson reliability coefficient (KR-20) was tested with 30 non-sample graduate students in the psychology program, yielding a KR-20 value of 0.78. Subsequently, the final 50 usable items, consisting of 10 questions related to each concept, were selected using four multiple-choice items (maximum score of 10 points for each concept). The posttest and the follow-up test aimed to evaluate students’ improvement after participating in the unplugged series of board game activities. All of the tests featured the same questions but differed in the sequence of the available answers, similar to the pretest. The average score out of 50 was applied in the subsequent analysis.

The participants were also provided with a journal in which to write their reflections as in response to three open-ended questions. These questions were designed to capture the learning experiences and thoughts as qualitative outcomes related to the newly developed learning model. This technique can offer a valuable opportunity to enhance the depth of understanding of the designed model. The journal has already been validated by three experts and was developed in accordance with suggestions from

Jamieson et al. (

2023).

3.4. Experimental Procedure and Data Analysis

The experimental procedure is presented in

Figure 1. All participants were enrolled in an 8-week experimental course, followed by 5 weeks of game-based learning activities for the experimental group or conventional teaching activities for the control group, along with 1 week for the follow-up phase. During the experimental procedure, there were two free weeks before the follow-up week to examine learning retention to determine whether the learned knowledge or skills had been maintained or if there had been any decline. Notably, conventional teaching, where the learner is a passive listener, involves delivering a sequential lecture on each developmental domain, similar to the experimental group. However, there was no interactive game or practical activity for monitoring engagement.

Before the experiment and only in the first week, all students completed a 30 minutes pretest before being allocated to groups. An experimenter then explained the rules and introduced the procedure depending on allocation to the experimental or control group. Subjects in the experimental group engaged in game-based learning, with their progress in each concept of infant development being recorded throughout the process, while the control group underwent conventional learning. Each week, students participated in a 50 minutes session playing one board game each week as follows: Week 1: infants and GM development; Week 2: infants and FM development; Week 3: infants and socio-emotional development; Week 4: language and comprehension; and Week 5: monitoring infant development. After each game, the participants in both the experimental and the control groups were required to write a reflective journal to reflect on what they had learned and experienced immediately to prevent forgetting for up to 10 minutes. At the conclusion of learning, the students took the 30 minutes posttest after the board game in Week 5 to assess their knowledge and understanding of infant development and surveillance. The follow-up phase required a 30 minutes test to be completed at Week 8, and then the answers to the test were provided to all students after the follow-up test.

As a quantitative analysis, the effectiveness of the model was statistically evaluated. To compare the knowledge and understanding of test scores related to infant development and surveillance among undergraduate psychology students in the experimental group, a one-way repeated measures ANOVA was applied among the three phases of pretest, posttest, and follow-up test. To confirm the main effect of the model, time, and their interaction, comparisons were conducted among these three phases. The differences between the experimental and control groups were analyzed using mixed-design ANOVA. Partial eta-squared was applied to declare the effect side as recommended by

Richardson (

2011).

In terms of qualitative analysis, the reflective journals were analyzed using content analysis. To ensure trustworthiness in this study, multiple strategies were employed, addressing credibility, transferability, dependability, confirmability, and reflexivity. Credibility was established through prolonged engagement, persistent observation from the researcher and assistants, triangulation of qualitative data sources, and member checking. The analysis involved two coders, including the researcher and trained assistants, who independently reviewed the data and assigned codes based on emerging themes. Pre-defined categories and coding instructions were created to ensure inter-coder reliability, and the coders were trained to maintain consistency. A reliability test was then conducted to compare the coders’ results and assess their level of agreement. Transferability was supported by providing detailed descriptions of each game’s features, the participants, and their learning experiences, which can inform psychologists' use or recommendations. Dependability was reinforced by maintaining an audit trail documenting the research process in each game each week. Confirmability was ensured through the researcher and assistants’ reflexivity, peer debriefing, and maintaining a reflective journal to track biases and decisions. Continuous reflexivity was practiced through self-reflection and engagement to contextualize findings. These measures collectively strengthened the study’s qualitative reliability and validity in exploring board games as a learning tool for infant developmental psychology.

4. Findings

The distribution of the data was examined by considering skewness and kurtosis values in conjunction with the Shapiro–Wilk test, in which nonsignificant results indicated that the data were normally distributed. The analysis revealed that the dependent variables at each phase, namely pretest, posttest, and follow-up, had skewness and kurtosis values within the acceptable range of +1 to 1 (

Bulmer, 1979;

Field, 2024). Additionally, the Shapiro–Wilk statistic showed no significant deviation from normality (

p > 0.05), indicating that the variables were normally distributed. To test for homogeneity of variance, Levene’s test was performed, which showed no significant results, indicating that the variables under study did not differ in variance across the pretest, posttest, and follow-up phases, as shown in

Table 3. As descriptions of the three-phase test scores, each board game score and average score are presented in

Table 4.

5. Results of the Quantitative Analysis

To assess the significance of differences in the three-phase testing scores throughout the designed series of board games or conventional learning related to infants’ develop-mental milestones and surveillance, a 2 × 3 mixed-design ANOVA of scores was performed, which revealed a significant interaction effect between groups and the three testing phases [F(2,56) = 30.27,

p < 0.01, partial η

2 = 0.34]. Additionally, both the main effects of groups and testing phase were significant [F(1,28) = 42.92,

p =< 0.01, partial η

2 = 0.42 and F(2,56) = 1058.28,

p < 0.01, partial η

2 = 0.94, respectively]. These findings demonstrated a significant difference between the groups as well as a significant difference within the groups across timepoints, as shown in

Table 5. The post hoc analysis indicated that the experimental group exhibited significantly higher scores than the control group at both posttest and follow-up phases, suggesting that this group’s scores were consistently higher [F(1,58) = 50.36,

p < 0.01, partial η

2 = 0.46; F(1,58) = 55.10,

p < 0.01, partial η

2 = 0.12, respectively], as presented in

Table 6.

Additionally, one-way repeated-measures ANOVA was performed to define differences among the three-phase testing scores throughout the studied groups. The assumption of sphericity was met, as assessed by Mauchly’s test of sphericity. The results showed significant differences over time in the experimental group [F(1,29) = 700.18, p < 0.01, partial η2 = 0.96]. Regarding the results in the repeated tests, post hoc analysis using the Wilcoxon rank test revealed a significant increase from the pretest score to the posttest score, from 18.63 ± 2.97 to 36.83 ± 1.96 (z = −4.78, p < 0.01), and from the pretest score to the follow-up score, from 18.63 ± 2.97 to 35.80 ± 2.21 (z = −4.79, p < 0.01), although no significant difference was found between posttest and follow-up (z = −1.82, p > 0.05). Conversely, the results for the control group also showed significant differences over time [F(1,29) = 149.20, p < 0.01, partial η2 = 0.83]. Post hoc analysis using the Wilcoxon rank test revealed a significant increase from pretest score to posttest score, from 19.93 ± 2.91 to 30.66 ± 4.33 (z = −4.78, p < 0.01), and from pretest score to follow-up score, from 19.93 ± 2.91 to 32.13 ± 1.54 (z = −4.78, p < 0.01), although no significant difference was found between posttest and follow-up (z = −1.87, p > 0.05).

6. Results of Qualitative Exploration

All reflective journal entries from the 30 participants in the control group were transcribed verbatim and analysed using content analysis, with the process guided by the principle of data saturation to ensure comprehensive coverage. The analysis revealed key dimensions of learning experiences under conventional instructional methods in developmental psychology. Firstly, many participants noted that the 50-minute instructional sessions felt rushed and insufficient for addressing complex developmental topics in depth, suggesting that extending the duration could enhance both understanding and engagement. Secondly, students reported experiencing cognitive fatigue due to the demand to memorise extensive developmental milestones, particularly those related to gross motor development within the first two years of life. The use of the DSPM (Developmental Surveillance and Promotion Manual), while recognised as essential for future psychological practice, was also cited as a significant source of mental strain. Lastly, participants expressed a strong desire for more engaging and supportive learning approaches, such as experiential activities, field visits, and the incorporation of educational games. These methods were perceived as potentially effective in reducing academic stress and improving knowledge retention, highlighting the limitations of traditional pedagogy and the need for more student-centred learning strategies in the context of developmental psychology education.

All text in the reflective journals of the 30 subjects in the experimental group were transcribed verbatim, producing 150 single-spaced pages of text. Using evidence of data saturation, content analysis of these transcripts identified three key dimensions of learning experiences with the designed series of board games: (a) design of the games, (b) reflection on the learning process, and (c) recommendations for improvement. Selected quotes are provided as evidence of the key dimensions, as shown in

Table 7.

Design of the games: The design format significantly supports the deepening of the understanding of various aspects of infant development. The format facilitates the easy recall of key terms and aids in synthesizing information regarding developmental stages across different domains. It also assists in reviewing content, allowing more rapid retrieval of previously learned knowledge. The use of board game designs already available on the market, such as the

Timeline board game,

Snakes and Ladders, and

Exploding Kittens (see

www.explodingkittens.com; accessed on: 25 January 2024), contributes to more rapid comprehension of the material without the need to learn complex rules, enabling more focus to be placed directly on the content.

Reflection on the learning process: Board games create an engaging learning environment by promoting the acquisition of knowledge in a fun and interactive way. The developed game format enhances the classroom atmosphere by fostering enjoyment, collaboration, and the freedom to choose responses while learning through play. It helps reduce the stress of memorizing large amounts of content, as playing the game reduces the burden of rote learning, encourages knowledge sharing, and increases the interaction among learners. Additionally, it is suitable for content review. However, some game designs may not allow players to cover all aspects of the content, which could lead to gaps in learning.

Recommendations: Board games can inspire students in their pursuit of the role of a psychologist by serving as a tool to enhance the understanding of key concepts. Psychologists can use board games to communicate important topics, such as mental and physical healthcare, regardless of their field—whether they work in schools, hospitals, or child-supported organizations. The flexibility of board games also allows them to be adapted to various settings. Additionally, psychology interns in the fourth year of a Thai psychology degree can use board games to foster understanding and create an engaging learning atmosphere during internships, especially when the challenges that they encounter align with educational objectives.

7. Discussion

This study aimed to assess the effectiveness of the designed series of board games for learning about infant development and surveillance among psychology students using a convergent mixed-method approach. The quantitative results showed significantly higher knowledge scores in the experimental group than in the control group. The gains were observed in the posttest and in the follow-up phase. A medium-to-high effect size in those differences was observed. Meanwhile, the qualitative phase, involving a structured reflective journal completed by all subjects in the experimental group, revealed three main themes: (a) design of the games, (b) reflection on the learning process, and (c) recommendations for improvement. The obtained qualitative insights reinforced the quantitative results, highlighting the effectiveness and positive reception of the board games. This study provides robust evidence supporting an approach that reduces the stress of rote learning and makes the learning process more enjoyable.

One key aim of the series of board games, specifically designed for Thai undergraduate psychology students, is to enhance the understanding of infant development and surveillance. The findings obtained in this study provide compelling evidence that training with a series of board games effectively enhances both the performance and the internal experiences of students, including thoughts and emotions about psychology when studying infant development and surveillance. The findings also align with and reinforce previous research in psychology on board game interventions related to developmental psychology, such as studies by

Laski and Siegler (

2014),

Prihadi et al. (

2018),

Boghian et al. (

2019),

Gasteiger and Moeller (

2021), and

Gashaj et al. (

2021) Additionally, this study offers valuable insights and practical recommendations for adding enjoyment to the learning process for successful active learning (

Murillo-Zamorano et al., 2021).

As expected in this study, the scores of tests on development and surveillance in infants improved after completing all board games. As the large effect size shows, the experimental group’s consistent improvement over time is not only statistically significant but also practically significant, with effect sizes indicating strong to moderate relationships, accounting for 94% of the variance between the intervention and the different phases of testing. The substantial differences in scores between groups across both the posttest and follow-up phases emphasize the practical importance of using this learning method to support infants’ developmental milestones and surveillance, while the effect size for the follow-up phase is medium, indicating that the difference in scores remained meaningful but less pronounced after a longer period. Future interventions should prioritize infants’ socio-emotional development, which has shown a marked decline in scores over time, as well as fine motor development, which has also experienced a significant reduction. In contrast, the control group using traditional learning methods showed less decline in these areas, indicating that their strategies merit further investigation for potential integration into future program enhancements for psychology students.

This study also highlighted certain challenges in developing an understanding that warrant further discussion. Although the knowledge of students in the experimental group was significantly higher than that of the control group after training, as found in previous studies by

Zielinski (

2019) and

Janyarat (

2023), debate remains about the extent to which practical implementation differs from conventional teaching methods. Board games can deepen understanding and improve interpersonal interactions, but their effectiveness in facilitating the construction of new knowledge has not been thoroughly examined (

Noda et al., 2019). Additionally, board games may be better suited for reinforcing previously learned material than for generating new knowledge, particularly on complex topics (

Martin et al., 2021). However, the findings of this study present the opposite view, showing that board games can be used to foster the development of new knowledge rather than being limited to retention purposes alone. Additionally, previous research may support the idea that infant development is not a particularly complex topic that cannot be developed into a board game mechanism, as it follows a chronological order, age-based developmental progression.

Effective educational board games should meet several key pedagogical and psychological criteria, including alignment with learning objectives, suitability for the target age group, inclusivity, relevance to the course content, and the integration of new concepts. Additionally, well-crafted games can promote critical thinking, problem-solving, creativity, and teamwork. These insights highlight the potential of board games as valuable tools for enriching the teaching of developmental psychology in higher education settings. The findings of this study align with previous research, confirming that games enhance enjoyment and motivation, particularly in group settings and over multiple sessions (

Mangundjaya & Wicaksana, 2022;

Revelle, 2013;

Strode, 2019). Adaptability and inclusivity ensure that educational board games cater to diverse styles of learning, abilities, and social interactions, making them more accessible (

Ranuharja et al., 2021). Additionally, integrating board games with traditional teaching methods enhances knowledge retention and application, reinforcing learning outcomes (

Gunbas & Eger Aydogmus, 2022;

Zulkifli et al., 2023). This study further highlights that well-designed educational board games can effectively support learning when they incorporate engaging mechanics, structured play patterns, enjoyment and motivational elements for longer periods, as shown in post-game and follow-up phases.

This study revealed a nonsignificant decline in scores at follow-up compared with the posttest measurement in the experimental group; however, a significant decline was found at the follow-up phase in the control group that underwent conventional teaching [t(29) = 3.54,

p < 0.01]. Regarding why the use of a series of board games with various structures might be more beneficial to learners, the effectiveness of educational games for learning is mainly driven by the incorporation of retrieval practice rather than the structure of the game itself (

Whitt & Haselgrove, 2023). In addition, integrating evidence-based learning principles into educational games can significantly increase their effectiveness. For example, interleaved practice in a game was reported to lead to greater efficiency in out-of-game performance compared with blocked practice, despite the latter yielding better results within the game itself (

Ben-David & Roll, 2023).

While board games are not a complete substitute for conventional teaching methods, they provide valuable support by enhancing students’ comprehension, engagement, and enjoyment of the learning process across various healthcare fields (

de Paula Uchôa et al., 2020;

Hajimoradkhani et al., 2017). Moreover, the feedback from the weekly reflective journal in this study revealed notable points about designing the games’ structure and rules. Research has shown that using simple rules and familiar board game concepts can enhance learning outcomes. Integrating board games into educational settings boosts student engagement, motivation, and knowledge retention (

Shanklin & Ehlen, 2017). Similar to the findings in previous studies, in the study by

Booker and Mltchell (

2021), playing a modified version of the game

Snakes and Ladders improved students’ grasp of qualitative research knowledge concepts, while

Shanklin and Ehlen (

2017) showed that playing

Monopoly deepened their understanding of financial accounting principles, while

Whitt and Haselgrove (

2023) presented similar findings for biological psychology. Well-designed board game-based learning experiences effectively reinforce understanding and promote active participation. Therefore, the choice of game mechanics is crucial, as it can significantly impact learning outcomes for students of psychology and related disciplines. The originality and contributions of the research are presented in

Figure 2.

8. Conclusions, Limitations, and Implications

In this study, the designed series of board games significantly deepened psychology students’ understanding of infant development and surveillance, demonstrating effective engagement and knowledge retention compared with conventional learning methods. The quantitative results showed higher scores in the experimental group, supported by qualitative insights from reflective journals, highlighting the positive impact of the interactive learning experiences.

However, there are some limitations of this study that should be considered. While the findings provide substantial insight into the efficacy of the designed board games, this study primarily focused on a specific demographic—undergraduate psychology students—limiting the generalizability of the results to other populations or educational contexts. The results may be more applicable to health-related students, such as nurses or medical students, learning about the DSPM rather than parents using it for infant development understanding and monitoring. Moreover, as in other studies involving students with a high GPA, the generalizability of our results to a broader range of lower-GPA students may be limited. Studies of a diverse range of students are needed to confirm the universal effectiveness of board games as a self-paced method of learning. In addition, the lack of an active control group in this study limits the ability to clearly determine the unique effects of the games. Introducing an active control group that participates in an alternative intervention would enhance the ability to draw definitive conclusions on the causal relationships in future research. Additionally, future research should explore the long-term efficacy of board games in diverse sequences in combination with other active teaching methods, and investigate how different game structures might influence knowledge acquisition and retention.

Despite the above limitations, the findings of this research are promising. The use of board games, rather than a single teaching method, creates a dynamic and immersive learning environment, blending creativity with engagement. This approach transforms developmental psychology concepts into experiential learning through storytelling, role-playing, and problem-solving. By incorporating scenario-based challenges and collaborative missions as a future direction for improvement, educators can design board games that foster critical reflection of delayed development and real-world application of DSPM guidelines. In addition to traditional methods like anchored instruction and small-group observation of infant assessments, board games offer a unique, interactive tool to reinforce concepts, such as those in the DSPM assessment. This innovative approach complements existing methods, enhances engagement, and improves content retention, addressing gaps in the literature.