The Perfect Storm for Teacher Education Research in English Universities: The Tensions of Workload, Expectations from Leadership and Research

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Initial Teacher Education or Training (ITE or ITT)?

1.2. The State and Status of University-Based Initial Teacher Education in England

1.3. Work of Academics in Initial Teacher Education

1.3.1. Omission

1.3.2. Trivialisation

1.3.3. Condemnation

1.4. Research Capacity and Expectations in Initial Teacher Education

2. Materials and Methods

- ○

- The ITE environment (workload, leadership roles, relationships).

- ○

- Workload challenges.

- ○

- Accreditation and Ofsted.

- ○

- The future of work in ITE.

3. Analysis

3.1. Sample Characteristics

3.2. Ethics

4. Results

4.1. Leaders’ Understanding of Teacher Education

Some went further in explaining the distinct nature of teacher education:‘It’s a great job. But very few folks in HE leadership understand ITE!’

‘SLT (Senior leadership team) try to understand, they really do—but ITE is an outlier in so many respects.’

Where leaders did have an understanding of the ITE sector, this was around requirements for Ofsted inspection and meeting DfE criteria rather than the theoretical, pedagogical, and philosophical aspects of teacher education. Where participants shared more detailed responses, they reported a complex range of misunderstandings and frustrations by leaders concerning the distinct nature of ITE.‘Leaders, I believe, know that they have to follow whatever requirements are set for ITE, and that is what seems to be the driving factor rather than a deep appreciation of what it means to be involved in teacher education.’

‘There is a relentless pressure to dumb down assignments and to standardise assignment formats. Workloads are overly burdensome. Staff autonomy is increasingly eroded. Senior management is incompetent and malicious. The relationship between research and teaching is grossly undervalued.’

Participants like the one above noted the lack of understanding at the leadership level between engaging in research and teaching student teachers, and other participants reported a similar issue with university leaders and government.‘ITT has always been, in my experience, restrictive and performative. This has only become more so in the last 2–3 years. There is an uneasy fit within traditional academic departments due to lack of a lived experience by senior leaders and comparative colleagues that impacts upon expectation and draws frustration and division. All of this simmers beneath the surface as a process of ’Keep Calm and Carry On’ for the students and, ultimately, the children continues.’

Many participants reported in text-based comments that universities (the micro level in this quote) do not understand the purpose and value of university ITE sufficiently well.‘My ambivalence about ITE is due to a) internal factors related to management not understanding the role and, consequently inbuilt sense of failure due to my lack of research output b) external factors, including hostile government’

Some participants felt very strongly about the lack of understanding from the government, and particularly the Department for Education, going as far as saying that the lack of understanding is a strategy rather than a blind spot.‘I feel very concerned for the future of the sector. The ascendancy of neo- liberal pollical intervention at the micro level has resulted in students being trained to perform a tick list of competencies that lack theoretical foundations rather than be educated- I see this as undermining professionalism. The same agenda devalues academic staff.’

‘This is the new normal, permanent revolution of a political class convinced that they know, and have always known, what ’the answers’ are to the issues the system faces, even as they change their minds about what those issues are or what should be done about them… Designed to “move quickly and break things”, ... this will be another half-baked disaster which we will have to work on.’

4.2. Workload and Its Impact

Some participants explored in further detail what might underpin over-work in the sector:‘Impossible workload, no tasks removed, only added, working evenings and weekends every week.’

The relational aspects of the role, as highlighted in work by Ellis et al. (2013), appear in many comments from participants. Pressures from other aspects of the role, such as supporting student mental health and well-being and securing school placements and training mentors, and the national context for ITE and the university sector are also reported as having an impact on workload in 2023/24.‘Because the role is so intense and so personal, it is almost impossible to switch off, and despite being part-time I still work well over my hours because it simply doesn’t fit into the workload regime that we have. We work in education with people and that doesn’t in any way fit into fixed hourly allocation.’

This includes a sense from participants that overwork has been normalised and accepted in the sector, particularly as the majority of ITE academics have worked for many years in schools, where intense workloads and overwork are also the expectation.‘The pressures are so huge. I’m constantly told I’m lucky to have a job that we need to increase numbers but are losing staff all the time. A number of my colleagues are off on long term medical leave for mental health, further exacerbating the workload for the rest of us.’

The recent overhaul of ITE in England, via the CCF, Market Review, and Accreditation processes, and associated rapid and wholesale redesign of courses and materials has also had an inevitable impact on academics and their attitude to the nature of their workloads.‘I answer these questions with the caveat that workload is manageable in comparison to how unmanageable it is in teaching English within secondary schools.’

Some participant comments reflected an intensification of workload because of changes in the sector, as well as an increase in work hours, and many linked this to policy reforms and implementation, such as the reaccreditation process.‘There is so much change all the time that I’ve chosen to not overthink/over prepare as it is likely whatever I do/produce will be replaced quickly. All feels a bit pointless so I’m protecting myself by disengaging slightly from the madness.’

This increase in workload was tied to its limiting impact on research in many of the text comments, with some participants identifying their perceptions on where this could be addressed and by whom.‘The persistent impact of the reaccreditation process, Ofsted, and internal university uncertainty has meant that I have felt on ’high alert’ for a very long time.’

‘Research is massively impacted by the excess expectations of ITE. I love ITE, but there is no doubt it is a time sink, and that is not recognised by management in a sufficient way to counterbalance (i.e., hire enough staff to reduce burden across all staff and allow for research time).’

4.3. Research Expectations and Opportunities

Others commented on researchers being undervalued because they specialise in ITE and identifying such attitudes as stemming from perceptions in the wider university:‘For the majority of the year, to get my own research done, I need to either start from 5 am, work into the night, or work at the weekend. So, because that has not always been possible (especially with a young family, but even if I didn’t have the kids, why should I have to do that??), my work gets pushed to the end of the year.’

Some reported low expectations of them in terms of research but had a sense of relief that little or no pressure existed in this area of their work:‘ITE staff are not seen as ’researchers’ and are not taken seriously at times. Our department is very supportive, and they try but are hidebound by the wider, bigger university.’

Some academics felt that only narrowly defined research that met the government agenda was welcomed by leaders:‘Because of finances all research hours were cut for most members of staff. I found it a relief because I didn’t need to find excuses for why I had no time whatsoever for doing research. There is never enough time to do the work allocated, and I’ve only survived by being paid part-time while working full-time.’

However, other academics reported high institutional expectations of them in terms of research that seem at odds with the rest of the role:‘Non-ITTECF research is not valued in my department- “trainees” are trained to be able to work in schools rather than engage critically with research from non-ideological perspectives that could broaden their capacity to educate children.’

Whilst expectations of research varied by institution, many responses described the tension between university narratives around the importance of being ‘research active’ and the local overwork of the ITE role, together with a lack of understanding from departmental leaders who did not have an interest in research.‘My research, my entire reason for being part of HE, is constantly pushed to second place because ’the day job’ is seen as most important. Yet, we are also being challenged to research, to write, to be part of a research culture that does not value ITE academics. Research is seen as a vanity project.’

Several participants commented on a lack of encouragement from leaders when it came to research activity, which had an impact on motivation. Four participants also reported having suspended or withdrawn from doctoral programmes due to workload and lack of support.‘Research is at the bottom of the list in ITE. Not all ITE staff are interested in writing papers or doing research, but I was very keen on this and found that little value was attached to it m. There is also resentment from other staff who, due to workload, are then burdened with your tasks if you are on conferences, writing retreats, or additional training sessions. It is a horrible environment to flourish in.’

Whilst this was not a significant theme in the overall data, with only 4 of the 167 participants commenting on this experience, it is important. ITE academics are often recruited from teaching posts, with little opportunity to engage in doctoral study beforehand; reduced opportunities to undertake high level research qualifications during their academic careers are likely to have an impact on the research capacity of the sector overall. Anecdotally, outside of the survey, whilst it is still common for those entering from schools to be expected to complete master’s degrees where necessary, there is an increasing lack of impetus for them to continue to study for doctorates, which are sometimes seen as a distraction.‘I have had to give up doing my doctorate due to workload. I do complete tasks efficiently and always meet deadlines, but this is only because I have been prepared to work at weekends and early mornings/late evenings. Other areas of my life have suffered as a result of this.’

5. Discussion

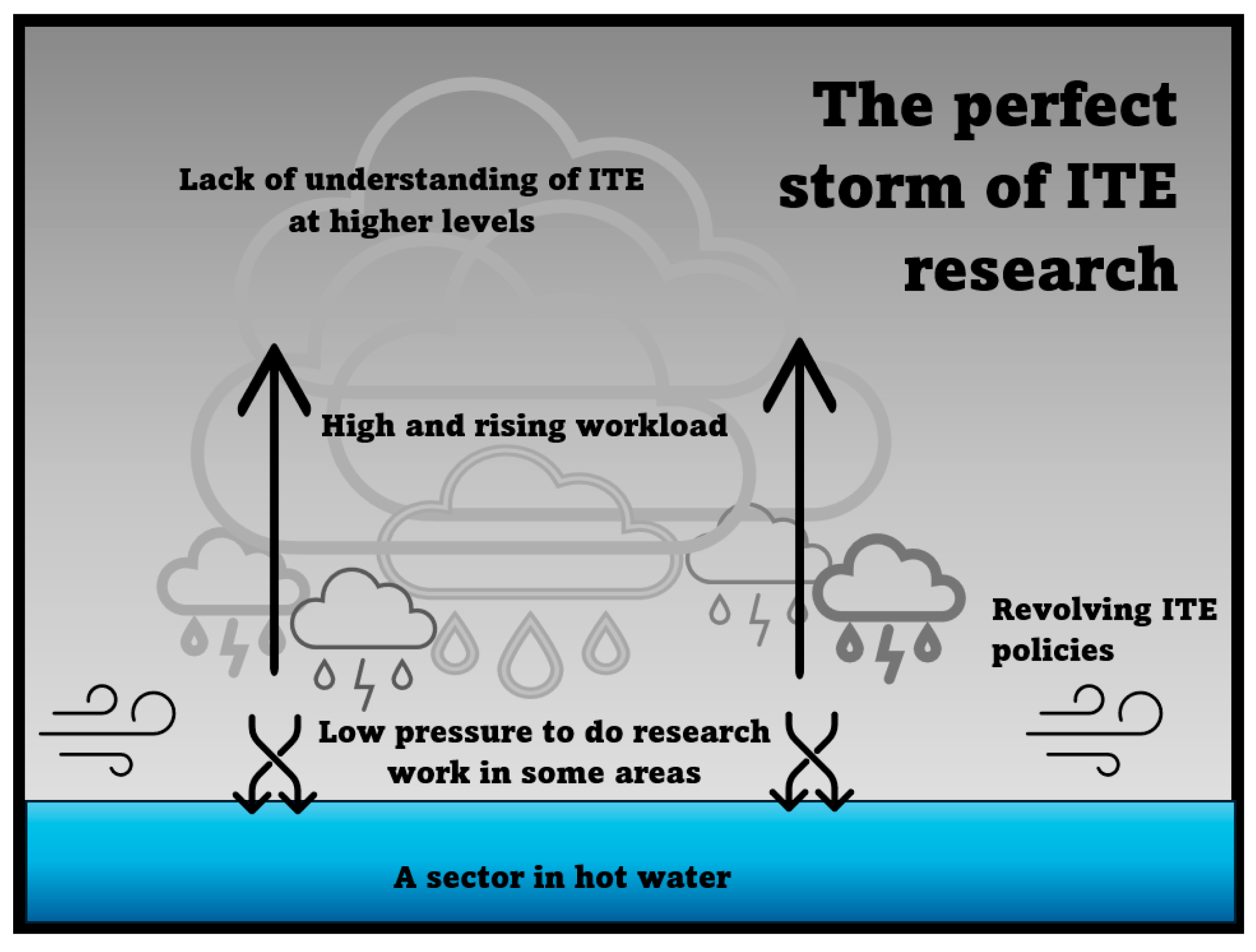

5.1. Low Pressure to Undertake Research

5.2. High and Rising Workload

5.3. Lack of Understanding of ITE at Higher Levels

5.4. Implications for the Sector

6. Recommendations

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bassey, M., & Pratt, J. (2003). How general are generalizations? In Educational research in practice, London, Continuum (pp. 164–171). Bloomsbury Publishing. Available online: http://digital.casalini.it/9780826432742 (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- BERA (British Educational Research Association). (2018). Ethical guidelines for educational research. Available online: https://www.bera.ac.uk/researchers-resources/publications/ethical-guidelines-for-educational-research-2018 (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, S. S. W., Thomas, M. A. M., & Mockler, N. (2023). Amplifying organisational discourses to the public: Media narratives of Teach for Australia, 2008–2020. British Educational Research Journal, 49(2), 231–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitty, C. (2009). Initial teacher training or education? ITT or ITE? FORUM, 51, 2. Available online: https://journals.lwbooks.co.uk/forum/vol-51-issue-2/article-3590/ (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Clapham, A., Richards, R., Lonsdale, K., & La Velle, L. (2023). Scarcely visible? Analysing initial teacher education research and the research excellence framework. London Review of Education, 21(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran-Smith, M. (2005). Researching teacher education in changing times: Politics and paradigms. In Studying teacher education: The report of the AERA panel on research and teacher education/American educational research association. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran-Smith, M. (2021). Rethinking teacher education: The trouble with accountability. Oxford Review of Education, 47(1), 8–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cochran-Smith, M., Villegas, A. M., Abrams, L., Chavez-Moreno, L., Mills, T., & Stern, R. (2015). Critiquing teacher preparation research: An overview of the field, part II. Journal of Teacher Education, 66(2), 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czerniawski, G., Gray, D., MacPhail, A., Bain, Y., Conway, P., & Guberman, A. (2018). The professional learning needs and priorities of higher-education-based teacher educators in England, Ireland and Scotland. Journal of Education for Teaching, 44(2), 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DfE (Department for Education). (2011). Teachers’ standards. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/teachers-standards (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- DfE (Department for Education). (2019). The ITT core content framework. DfE.

- DfE (Department for Education). (2021). Initial teacher training (ITT) market review report. DfE. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/initial-teacher-training-itt-market-review-report (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- DfE (Department of Education). (2022). Initial teacher training (ITT): Accreditation. DfE. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/initial-teacher-training-itt-accreditation (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- DfE (Department for Education). (2023). Initial teacher training (ITT): Criteria and supporting advice. DfE.

- DfE (Department for Education). (2024). Initial teacher training early career framework. DfE.

- Ellis, V., & Childs, A. (2024). Introducing the crisis: The state, the market, the universities and teacher education in England. In V. Ellis (Ed.), Teacher education in crisis: The state, the market and the universities in England (pp. 1–26). Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, V., Glackin, M., Heighes, D., Norman, M., Nicol, S., Norris, K., Spencer, I., & McNicholl, J. (2013). A difficult realisation: The proletarianisation of higher education-based teacher educators. Journal of Education for Teaching, 39(3), 266–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geerdink, G., Boei, F., Willemse, M., Kools, Q., & Van Vlokhoven, H. (2016). Fostering teacher educators’ professional development in research and in supervising student teachers’ research. Teachers and Teaching, 22(8), 965–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibb, N. (2014, April 23). Teaching unions aren’t the problem—Universities are. The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2014/apr/23/teaching-unions-arent-problem-universities-schools-minister (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Gill, J. (2024, April 11). Lessons to be learned. Times Higher Education. Available online: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/opinion/lessons-be-learned (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Hordern, J., & Brooks, C. (2023). The core content framework and the ‘new science’ of educational research. Oxford Review of Education, 49(6), 800–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoult, E. C., Durrant, J., Holme, R., Lewis, C., Littlefair, D., McCloskey-Martinez, M., & Oberholzer, L. (2024). The contribution of Teacher education to universities: A case study for international teacher educators. Teachers and Teaching, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- la Velle, L. (2023). The teacher educator: Pedagogue, researcher, role model, administrator, traveller, counsellor, collaborator, technologist, academic, thinker ………. Compliance or autonomy? Journal of Education for Teaching, 49(1), 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- la Velle, L., Newman, S., Montgomery, C., & Hyatt, D. (2020). Initial teacher education in England and the COVID-19 pandemic: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of Education for Teaching, 46(4), 596–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leahy, K., Calderón, A., O’Meara, N., MacPhail, A., & O’Flaherty, J. (2025). Navigating times of change through communities of practice: A focus on teacher educators’ realities and professional learning. Teaching and Teacher Education, 156, 104925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malm, B. (2020). On the complexities of educating student teachers: Teacher educators’ views on contemporary challenges to their profession. Journal of Education for Teaching, 46(3), 351–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLean, D., Worth, J., & Smith, A. (2024). Teacher labour market in England: Annual report 2024. NFER. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, R., Perry, T., Smith, E., & Pilgrim-Brown, J. (2023). Education: The state of the discipline. A survey of education researchers’ work, experiences and identities. British Educational Research Association. Available online: https://www.bera.ac.uk/publication/education-the-state-of-the-discipline-survey-of-education-researchers (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Murray, J., & Kosnik, C. (2011). Academic work and identities in teacher education. Journal of Education for Teaching, 37(3), 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutton, T., & Burn, K. (2024). Does initial teacher education (in England) have a future? Journal of Education for Teaching, 50(2), 214–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oancea, A., Fancourt, N., Robson, J., Thompson, I., Childs, A., & Nuseibeh, N. (2021). Research capacity-building in teacher education. Oxford Review of Education, 47(1), 98–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, I. (2013). Doing the ‘Second Shift’: Gendered labour and the symbolic annihilation of teacher educators’ work. Journal of Education for Teaching, 39(3), 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spendlove, D. (2024). The state of exception: How policies created the crisis of ITE in England. In V. Ellis (Ed.), Teacher education in crisis: The state, the market and the universities in England (pp. 43–61). Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swennen, A., Jones, K., & Volman, M. (2010). Teacher educators: Their identities, sub-identities and implications for professional development. Professional Development in Education, 36(1–2), 131–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, K., & Garvis, S. (2023). Teacher educator wellbeing, stress and burnout: A scoping review. Education Sciences, 13(4), 351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Universities’ Council for the Education of Teachers (UCET). (2020). The intellectual base of teacher education. UCET. Available online: https://www.ucet.ac.uk/downloads/11676%2DIntellectual%2DBase%2Dof%2DTeacher%2DEducation%2Dreport%2D%28updated%2DFeb%2D2020%29.docx (accessed on 10 October 2024).

- Van Katwijk, L., Jansen, E., & Van Veen, K. (2023). Pre-service teacher research: A way to future-proof teachers? European Journal of Teacher Education, 46(3), 435–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Nuland, S., Dinitsa-Schmidt, S., Assunção Flores, M., Hordatt Gentles, C., la Velle, L., & Ruttenberg-Rozen, R. (2024). Changes in teacher education provision: Comparative experiences internationally. Journal of Education for Teaching, 50(2), 341–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, A. (2022, December 8). ITT review: DfE rejects all accreditation appeals. Schools Week. Available online: https://schoolsweek.co.uk/itt-review-dfe-rejects-all-accreditation-appeals/#:~:text=All%20appeals%20made%20by%20teacher,operating%20in%20England%20last%20year (accessed on 8 December 2022).

- Wood, P., & Quickfall, A. (2024). Was 2021–2022 an Annus Horribilis for teacher educators? Reflections on a survey of teacher educators. British Educational Research Journal, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A. M., Ní Dhuinn, M., Mitchell, E., Ó Conaill, N., & Uí Choistealbha, J. (2022). Disorienting dilemmas and transformative learning for school placement teacher educators during COVID-19: Challenges and possibilities. Journal of Education for Teaching, 48(4), 459–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Question | 2021/22 (n = 159) | 2022/23 (n = 142) | 2023/24 (n = 166) |

|---|---|---|---|

| I enjoy working in a university ITE role | 85% | 83% | 87% |

| I have supportive colleagues to work with | 90% | 94% | 93% |

| I enjoy working with ITE students | 97% | 99% | 99% |

| The leaders of my institution are supportive of ITE | 65% | 46% | 31% |

| The leaders of my department are supportive of ITE | n/a | 81% | 81% |

| The leaders of my institution understand ITE | 53% | 28% | 51% |

| 2021/22 | 2022/23 | 2023/24 |

|---|---|---|

| 159 participants | 142 participants | 167 participants |

| Question | 2021/22 (n = 159) | 2022/23 (n = 142) | 2023/24 (n = 166) |

|---|---|---|---|

| The leader of my institution understand ITE | 53% | 28% | 51% |

| Question | 2021/22 (n = 159) | 2022/23 (n = 142) | 2023/24 (n = 166) |

|---|---|---|---|

| My workload has been manageable this year | 29% | 25% | 25% |

| I can easily ‘switch off’ from work, outside of my work hours | 18% | 18% | 26% |

|

I have enough time to get my work done this year, to a standard acceptable to me | 25% | 29% | 28% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Quickfall, A.; Wood, P. The Perfect Storm for Teacher Education Research in English Universities: The Tensions of Workload, Expectations from Leadership and Research. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 434. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040434

Quickfall A, Wood P. The Perfect Storm for Teacher Education Research in English Universities: The Tensions of Workload, Expectations from Leadership and Research. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(4):434. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040434

Chicago/Turabian StyleQuickfall, Aimee, and Philip Wood. 2025. "The Perfect Storm for Teacher Education Research in English Universities: The Tensions of Workload, Expectations from Leadership and Research" Education Sciences 15, no. 4: 434. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040434

APA StyleQuickfall, A., & Wood, P. (2025). The Perfect Storm for Teacher Education Research in English Universities: The Tensions of Workload, Expectations from Leadership and Research. Education Sciences, 15(4), 434. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040434