Attributes and Knowledge of the Lead Organizer in Planning a Virtual Teacher Professional Development Series: The Case of the Organizer of the Schoolyard Network

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- What is the organizational structure that supports the lead organizer of the Schoolyard Network to make pedagogical choices for this PLC?

- (2)

- What experiences does the lead organizer have that drive the Schoolyard Network?

2. Organizational Background and Theory

2.1. Background on the Great Smoky Mountain Institute at Tremont

2.2. Background on GSMIT’s Educator Programming

3. Materials and Methods

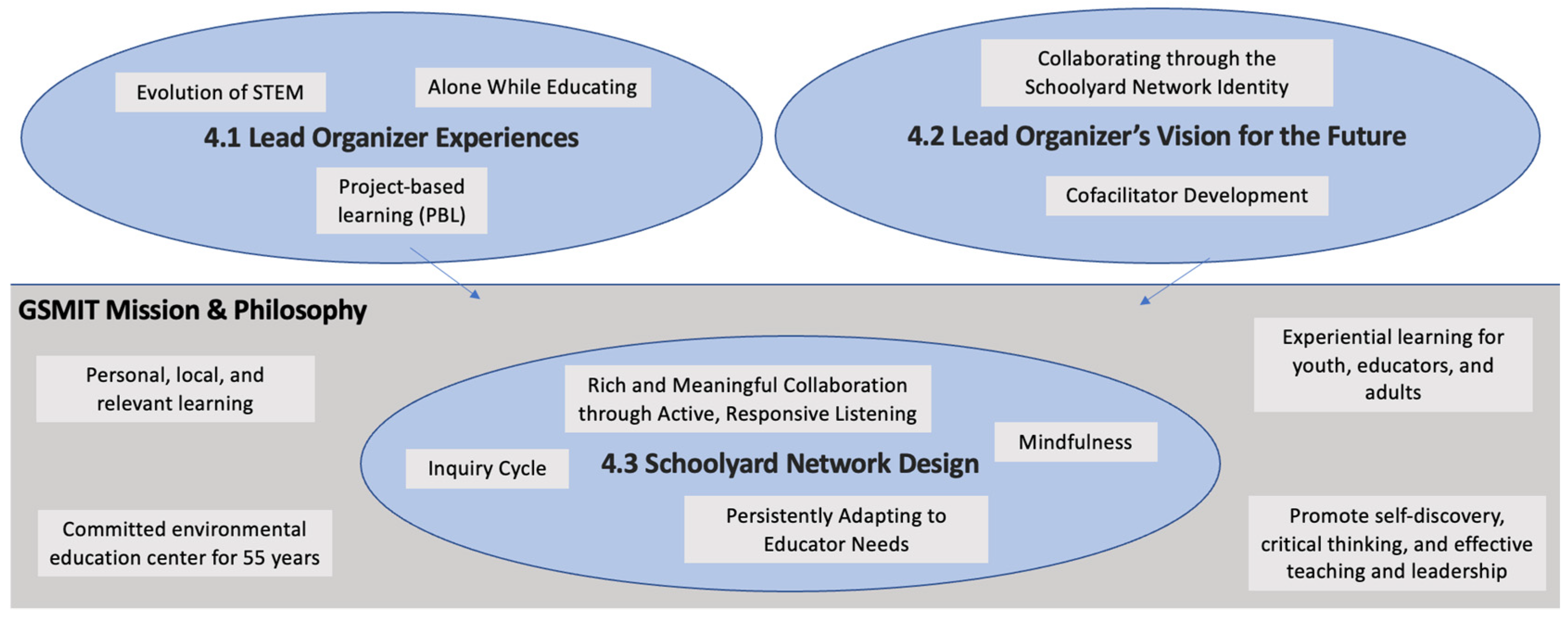

4. Results

4.1. Lead Organizer Experiences

4.1.1. Alone While Education

“And I felt alone constantly. I felt on an island. I was the only ESL teacher in our building and just so like I had to figure it out myself in every definition of that of that word. It was hard. So you know, I kind of came into teaching feeling like it’s a like figure it-out-for-yourself job and I did. But it wasn’t that sense of community that I think in undergrad we were all hoping we’re for like, oh, we’re all going, like, plan together and think about how kids can work together and like there’s all these visions of what could be and that unfortunately, at the beginning of my career was not the reality I was faced.”

4.1.2. Project-Based Learning

“And in that school, we saw and approached teaching and learning as through-line questions. So how do we make learning connected so that our students are seeing that math and English and science and history and social concerns are not separate, but they all build off of another, interact with each other, and are connected and in traditional schooling it’s like you get 45 min of math, you get 45 min of the science and they never talk to each other. And at this school, there was an opportunity for kids to see and make meaning across content areas. And because of that, it really leveraged teacher collaboration so that teachers are talking to another, planning with one another, and feeling empowered to help their students make those connections.”

4.1.3. Evolution of STEM

“But everybody was like, you’re a good reader and writer like you should, like, go into English. And so I just listened to that because that’s what I was like told I was good at. So, but I never loved it. I never felt in those classes the way I saw other students feel in those classes, but in my science classes, I felt that excitement.”

4.2. Lead Organizer’s Vision for the Future

“I think it’s important that we build systems and not just people.”“And so we have those conversations in our reflection time of like, what did we think went well? What do we want to think about next time? to give her space to grow as a facilitator.”

4.2.1. Cofacilitator Development

“You have to kind of try on what feels right and what feels right might not be what you thought … it would be at the beginning.”“At the call at the activity level, at the call level, at the yearlong planning level, and at the multiyear long planning level like we do regardless of how we facilitate need to know where we’re headed and why and let that be the guiding like North Star of you know making all the decisions in the in between.”“Whether it’s kids with behavior or adults with confusion, like a lot of that is born out of gray space. So, if we can eliminate the gray space with the clarity of the directions we’re giving, we’re setting all people up for success, and that can take practice too.”

4.2.2. Collaborating Through the Schoolyard Network Identity

“We always like call it watercooler talk, sometimes the most valuable things you get out of an experience are during that watercooler talk time because you have this question and you are talking and walking with this other person that you can ask it to or you heard them say something that was really inspiring to you or that you want to try.”

4.3. Schoolyard Network Design

4.3.1. Rich and Meaningful Collaboration Through Active, Responsive Listening

“And sometimes, like people, whether it’s a teacher or not, need just somebody to listen. And like affirm and nod and like, give that active listening body language. Sometimes people need a coach where you are helping them, like, come to an answer. But they have the answer in their brain and you’re asking questions to help them pull that answer out. And they are like solving their own problem through that process. And sometimes people need to consultant. Sometimes you’re just like I need the answer. I want you to give me the answer. Like, what would you do?”

“What everybody else can’t see is that I have the chat open the whole time. And so oftentimes I’m chatting one on one with people in the group and they will I be like, hey, just checking in like or it’s nice to see you. And even just like that greeting or that like that invitation into this space will later lead to, like actually had this question that I didn’t want to ask whole group and we’re like typing about that back and forth.”

“I’m inviting you to do this … that in that intentional language of invitation. It is born out of really valuing that people feel seen, that we care about what they say and what they’re sharing.”

4.3.2. Persistently Adapting to Educator Needs

“What kind of feedback do I give a struggling student on this activity?”“How do I encourage my students to ask deeper questions that push their thinking?”

“We met each other in person this summer, and they didn’t know each other before the Schoolyard Network. Had never talked, never met, they didn’t even live in the same state. And then, (they) decided to meet up over the summer to hang out in person.”

“We built in the parking lot time at the end because I was feeling disconnected with some of the participants. And I’m like, I don’t really know where like in what sense are you feeling good about taking this and putting it into practice? And where are you feeling hesitant or what things are top of mind for you right now?”

4.3.3. Mindfulness

“So recognizing that regardless of what you’re day has looked like, there’s just a lot of noise happening for all of us, whether it’s in our own lives or things happening in the world. Your to do list is like constantly growing so giving people the permission and inviting them to connect with themselves and release the day so that they feel like they can be fully present with the next hour and a half that lies in front of them, with the people that are there and the things that they’re going to be doing. I have heard a lot of feedback of just how nice that feels, how powerful it is. Oftentimes you can see the difference in demeanor even on screen of like pre-mindful moment and post.”

“Teachers say, like I didn’t know how badly I needed this. Like I’m leaving here with ideas for my classroom, and also I’m leaving here feeling like I have a had a reset as a human and we value those things equally because it’s like we can only be as good of teachers as we feel. And so valuing the whole person not just that career aspect of person is really important in trying to be intentional with that.”

4.3.4. Inquiry Cycle

“I love that we are working with this inquiry framework because it is applicable no matter what you’re teaching. Like inviting kids into a learning experience, encouraging them to get curious and tap into background knowledge, exploring and asking questions and struggling through something that you don’t quite, you don’t quite get yet. And then making time for reflection. If we could all do that in our teaching and think about teaching experiences, learning experiences, in that way, I think that is a step forward.”

“A broader philosophy that I would say I aligned with at Tremont in that there is a quote that says, “when you teach someone something, you are robbing them of the opportunity of learning it.”

5. Discussion

- Prioritizing rich and meaningful collaboration through active, responsive listening;

- Persistently adapting to educator needs;

- Utilizing mindfulness techniques;

- Delivering session material through the inquiry cycle.

- Lead organizers of PLCs should provide in-person opportunities that can help build relationships, grounded in an organization’s mission and philosophy. From the lead organizer’s perspective, there was a clear connection in attending in-person events (i.e., the Schoolyard Escape), for multiple reasons including how visits to GSMIT helped educators engage in the professional development on a deeper level, but also to prioritize utilizing local places and investigations (Bocko et al., 2023).

- There is a palatable difference between inquiry-based virtual instructions and lecture-driven methods, both in what content is retained by participants and the impact on participant well-being (Pinheiro & Alves, 2024). As PLC session design decisions are made, finding places to have participants “put on the learner hat” should be prioritized.

- Organizers should intentionally develop a structure with multiple cofacilitators, ideally tiering leadership based on experience, attributes, and training as research suggests (de Jong et al., 2023). Staggering experience levels within the program so that cofacilitators not only understand the direction of the program but more importantly, connect with regular participants during sessions is essential to maintaining a virtual environment that educators will continue to join, even during the busiest months of the year.

- Providing the PLC’s educators the opportunity to rethink instruction outside provides unique pedagogical opportunities that are hard to create inside a school. PLC organizers should consider using alternative, appealing, and convenient environments for sessions.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aasen, W., Grindheim, L., & Waters, J. (2009). The outdoor environment as a site for children’s participation, meaning-making and democratic learning: Examples from Norwegian kindergartens. Education 3-13, 37(1), 5–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basit, T. (2003). Manual or electronic? The role of coding in qualitative data analysis. Educational Research, 45, 143–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binns, I., Polly, D., Conrad, J., & Algozzine, B. (2016). Student perceptions of a summer ventures in science and mathematics camp experience: STEM perceptions. School Science and Mathematics, 116, 420–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bintz, J., Galosy, J., Miller, B., & Mohan, L. (2017). A synthesis of math/science teacher leadership development programs: Consensus findings and recommendations (No. 02). BSCS. [Google Scholar]

- Bocko, P., Jorgenson, S., & Malik, A. (2023). Place-based education: Dynamic response to current trends (pp. 137–150). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, J. (2014). Avoiding traps in member checking. The Qualitative Report, 15(5), 1102–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrier, S. J., Thomson, M. M., Tugurian, L. P., & Stevenson, K. T. (2014). Elementary science education in classrooms and outdoors: Stakeholder views, gender, ethnicity, and testing. International Journal of Science Education, 36(13), 2195–2220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Correia, M., Ribeirinha, T., Beirante, D., Santos, R., Ramos, L., Dias, I. S., Luís, H., Catela, D., Galinha, S., Arrais, A., Portelada, A., Pinto, P., Simões, V., Ferreira, R., Franco, S., & Martins, M. C. (2024). Outdoor STEAM education: Opportunities and challenges. Education Sciences, 14(7), 688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CoSTEM. (2018). Charting a course for success: America’s strategy for STEM education. Committee on STEM Education (CoSTEM) of the National Science & Technology Council. Available online: https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/STEM-Education-Strategic-Plan-2018.pdf (accessed on 21 September 2024).

- Creswell, J. W. (1998). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions (pp. xv, 403). Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Darling-Hammond, L., Burns, D., Campbell, C., Goodwin, A. L., Hammerness, K., Low, E. L., McIntyre, A., Sato, M., & Zeichner, K. (2017a). Empowered educators: How high-performing systems shape teaching quality around the world. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Darling-Hammond, L., Hyler, M. E., & Gardner, M. (2017b). Effective teacher professional development. Learning Policy Institute. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED606743 (accessed on 21 September 2024).

- Davies, R., & Hamilton, P. (2018). Assessing learning in the early years’ outdoor classroom: Examining challenges in practice. Education 3–13, 46(1), 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jong, W. A., de Kleijn, R. A. M., Lockhorst, D., Brouwer, J., Noordegraaf, M., & van Tartwijk, J. W. F. (2023). Collaborative spirit: Understanding distributed leadership practices in and around teacher teams. Teaching and Teacher Education, 123, 103977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drew, C. (2023). 10 case study advantages and disadvantages. Available online: https://helpfulprofessor.com/case-study-advantages-and-disadvantages/ (accessed on 17 February 2025).

- DuFour, R. (2004). What is a “Professional learning community”? Educational Leadership, 61(8), 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Dyment, J. E., & Reid, A. (2005). Breaking new ground? Reflections on greening school grounds as sites of ecological, pedagogical, and social transformation. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education, 10, 286–301. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards-Jones, A., Waite, S., & Passy, R. (2016). Falling into LINE: School strategies for overcoming challenges associated with learning in natural environments (LINE). Education 3-13, 46(1), 49–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elias, M., Zins, J., Graczyk, P., & Weissberg, R. (2003). Implementation, sustainability, and scaling up of social emotional and academic innovations in public schools. School Psychology Review, 32, 303–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erawan, P., & Erawan, W. (2024). Effective approaches to teacher professional development in Thailand: Case study. Journal of Education and Learning, 13(2), 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espedal, G., Jelstad Løvaas, B., Sirris, S., & Wæraas, A. (Eds.). (2022). Researching values: Methodological approaches for understanding values work in organisations and leadership. Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairman, J., David, S., Pullen, P., & Lebel, S. (2020). The challenge of keeping professional development relevant. Professional Development in Education, 49(2), 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feille, K. K. (2017). Teaching in the field: What teacher professional life histories tell about how they learn to teach in the outdoor learning environment. Research in Science Education, 47(3), 603–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, J., Lawless, J., & Roulston, K. (2004). Discursive approaches to clinical research. In T. Strong, & D. Paré (Eds.), Furthering talk: Advances in the discursive therapies (pp. 125–144). Springer US. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamage, K. A. A., Ekanayake, S. Y., & Dehideniya, S. C. P. (2022). Embedding sustainability in learning and teaching: Lessons learned and moving forward—Approaches in STEM higher education programmes. Education Sciences, 12(3), 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GSMIT. (2023a). Mission and history. Mission & history: Great smoky mountain institute at Tremont. Available online: https://gsmit.org/about/mission-and-history/ (accessed on 21 September 2024).

- GSMIT. (2023b). The schoolyard network. Welcome to Tremont’s schoolyard network: Great smoky mountain institute at Tremont. Available online: https://gsmit.org/educators/schoolyard-network/ (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- GSMIT. (2023c). School trips to tremont. Great Smoky Mountain Institute at Tremont. Available online: https://gsmit.org/schools/ (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Gu, Q., & Day, C. (2007). Teachers resilience: A necessary condition for effectiveness. Teaching and Teacher Education, 23(8), 1302–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huggins, V. (2012). Risk and adventure in early years outdoor play: Learning from forest schools, and Forest schools for all. Early Years, 32(1), 99–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, L., Walker, R., Tenenbaum, Z., Sadler, K., & Wissehr, C. (2015). Why the secret of the great smoky mountains institute at tremont should influence science education—Connecting people and nature (pp. 265–279). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, P. (2007). Growing physical, social and cognitive capacity: Engaging with natural environments. International Education Journal, 8(2), 293–303. [Google Scholar]

- Largo-Wight, E., Guardino, C., Wludyka, P. S., Hall, K. W., Wight, J. T., & Merten, J. W. (2018). Nature contact at school: The impact of an outdoor classroom on children’s well-being. International Journal of Environmental Health Research, 28(6), 653–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M., Kim, J. W., Mo, Y., & Walker, A. D. (2022). A review of professional learning community (PLC) instruments. Journal of Educational Administration, 60(3), 262–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S. (2019). An outdoor professional development model in the era of the next generation science standards—ProQuest. Mississippi State University. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/7539463addabf5c0054cd2c702d0a3d9/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y (accessed on 25 August 2024).

- Madalinska-Michalak, J. (2015). Developing emotional competence for teaching. Croatian Journal of Education, 17(2), 71–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynard, T., & Waters, J. (2007). Learning in the outdoor environment: A missed opportunity? Early Years, 27(3), 255–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M., & Huberman, A. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed.). SAGE Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2021). The inequalities-environment nexus: Towards a people-centred green transition. OECD. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinheiro, G., & Alves, J. M. (2024). Organizational learning within the context of the functioning of educational teams: The progressive emergence of a professional metamorphosis. Education Sciences, 14(3), 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokhrel, S., & Chhetri, R. (2021). A literature review on impact of COVID-19 pandemic on teaching and learning. Higher Education for the Future, 8(1), 133–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, A., & Bellamy, J. (2012). Practitioner’s guide to using research for evidence-based practice (2nd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Sahu, P. (2020). Closure of universities due to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): Impact on education and mental health of students and academic staff. Cureus, 12(4), e7541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldaña, J. (2013). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (2nd ed.). SAGE Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Sassi, A., Bopardikar, A., Kimball, A., & Michaels, S. (2013, April 3–6). From “sharing out” to “working through ideas”: Helping teachers transition to more productive science talk. Annual Meeting of the National Association for Research in Science Teaching, Rio Grande, Puerto Rico. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, P. K., Smith, C., Osborn, R., & Samara, M. (2008). A content analysis of school anti-bullying policies: Progress and limitations. Educational Psychology in Practice, 24(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoll, L. (2020). Creating capacity for learning: Are we there yet? Journal of Educational Change, 21(3), 421–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoll, L., Bolam, R., McMahon, A., Wallace, M., & Thomas, S. (2006). Professional learning communities: A review of the literature. Journal of Educational Change, 7(4), 221–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarkar, P. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on education system. International Journal of Advanced Science and Technology, 29, 3812–3814. [Google Scholar]

- Tate, M. (2012). “Sit and get” won’t grow dendrites: 20 professional learning strategies that engage the adult brain. Corwin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, C. (2012). Quantitative reasoning and sustainability. Numeracy, 5(2), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- The Regents of the University of California. (2024). BEETLES: Science and teaching for field instructors. Beetles Project. Available online: https://beetlesproject.org/about/ (accessed on 21 September 2024).

- Thomas, G. (2021). How to do your case study. SAGE Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Education. (2024). YOU belong in STEM. Available online: https://www.ed.gov/about/ed-initiatives/you-belong-stem (accessed on 21 September 2024).

- van Dijk-Wesselius, J. E., van den Berg, A. E., Maas, J., & Hovinga, D. (2020). Green schoolyards as outdoor learning environments: Barriers and solutions as experienced by primary school teachers. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yli-Panula, E., Jeronen, E., Vesterkvist, S., & Mulari, L. (2023). Subject student teachers’ perceptions of key environmental problems and their own role as environmental problem solvers. Education Sciences, 13(8), 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Daiga, M.; Hessick, M. Attributes and Knowledge of the Lead Organizer in Planning a Virtual Teacher Professional Development Series: The Case of the Organizer of the Schoolyard Network. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 422. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040422

Daiga M, Hessick M. Attributes and Knowledge of the Lead Organizer in Planning a Virtual Teacher Professional Development Series: The Case of the Organizer of the Schoolyard Network. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(4):422. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040422

Chicago/Turabian StyleDaiga, Michael, and Mackenzie Hessick. 2025. "Attributes and Knowledge of the Lead Organizer in Planning a Virtual Teacher Professional Development Series: The Case of the Organizer of the Schoolyard Network" Education Sciences 15, no. 4: 422. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040422

APA StyleDaiga, M., & Hessick, M. (2025). Attributes and Knowledge of the Lead Organizer in Planning a Virtual Teacher Professional Development Series: The Case of the Organizer of the Schoolyard Network. Education Sciences, 15(4), 422. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040422