Modeling the Factors That Determine Sustainable Development Goal 12 in University Students

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Framework

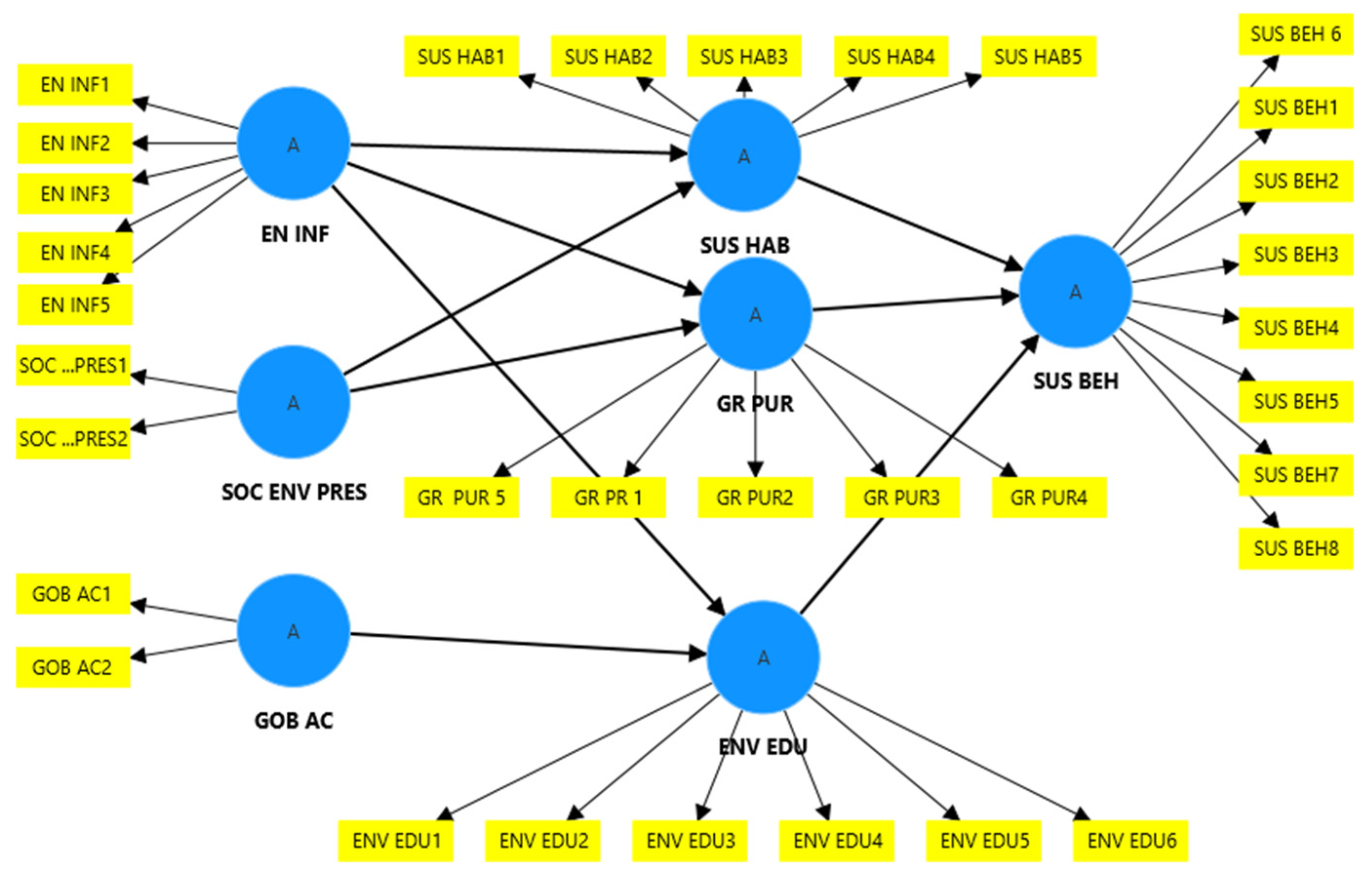

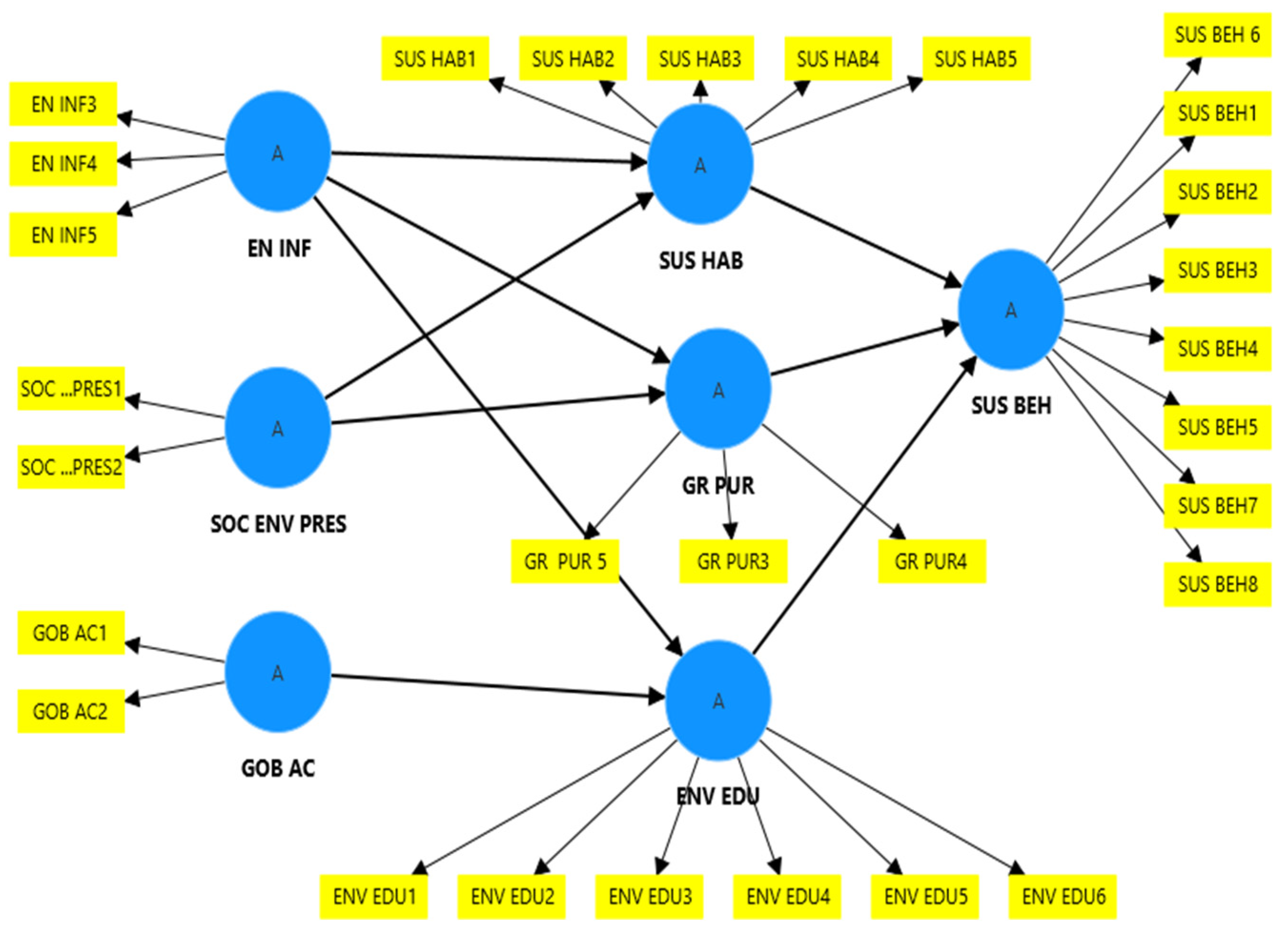

- Sustainable Consumption Behavior (SUS BEH) refers to the responsible use of goods and services to minimize environmental impact and ensure the conservation of natural resources for current and future generations.

- Sustainable Consumption Habits (SUS HAB) refer to the practices individuals can adopt to lead more sustainable lifestyles and positively impact society. This includes actions such as consuming less, selecting products with lower environmental impacts and reducing the carbon footprint associated with everyday activities.

- Green Purchasing (GR PURCH) refers to the practice of buying products and services that have a lower impact on human health and the environment compared to similar options. For a purchase to be considered green, it must meet specific criteria that demonstrate a reduced environmental footprint. This concept is related to consumer trends and habits, such as a growing preference for organic products over conventional ones.

- Environmental Education and Information (ENV EDU) empowers individuals to explore environmental issues, engage in problem-solving, and take action to improve the environment. This process promotes a deeper understanding of environmental challenges and helps develop the skills necessary for making informed and responsible decisions. Key topics include awareness and sensitivity to environmental challenges, knowledge and understanding of environmental issues, attitudes that reflect concern for the environment, and motivation to enhance or preserve the environment.

- Environmental Influence (ENV INF) refers to various conditions in the surrounding environment, as well as structures and external sources such as friends, family, communities, and social or technological factors that can affect individual development.

- Social Environmental Pressure (SOC PR) refers to the different conditions or groups that can influence individual development by applying various forms of pressure. Cultural and social norms also establish expectations for how individuals should behave in different contexts. Additionally, media and social networks can exert significant pressure by setting behavioral standards related to the environment.

- Government Action (GOB AC) includes initiatives by local authorities aimed at fostering environmental stewardship among community members. These efforts seek to inspire community members to actively participate in the care of our shared environment.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Aim and Participants

3.2. Research Model

- Government Action and Environmental Education (H1-a, RQ1)

- 2.

- Social Environmental Pressure and Sustainable Behavior (H2-a, H2-b, RQ2, RQ3)

- 3.

- Environmental Influence and Sustainable Habits (H3-a, H3-b, H3-c, RQ4, RQ5, RQ6)

- 4.

- Environmental Education and Sustainable Behavior (H4, RQ7)

- 5.

- Sustainable Habits and Sustainable Behavior (H5, RQ8)

- 6.

- Green Purchase and Sustainable Behavior (H6, RQ9)

3.3. Research Hypothesis

- -

- RQ1 (H1-a). Government Action correlates positively with Environment Education and Information.

- -

- RQ2 (H2-a). Social environmental pressure correlates positively with Green Purchase.

- -

- RQ3 (H2-b). Social environmental pressure correlates positively with Sustainable Consumption Habits.

- -

- RQ4 (H3-a). Environmental Influence correlates positively with Sustainable Consumption Habits.

- -

- RQ5 (H3-b). Environmental Influence correlates positively with Green Purchase.

- -

- RQ6 (H3-a). Environmental Influence correlates positively with Environmental Education and Information.

- -

- RQ 7 (H4). Environmental Education and Information influence Sustainable Behavior.

- -

- RQ 8 (H5). Sustainable Habits correlate positively with Sustainable Behavior.

- -

- RQ 9 (H6). Green Purchase influences Sustainable Consumption Behavior.

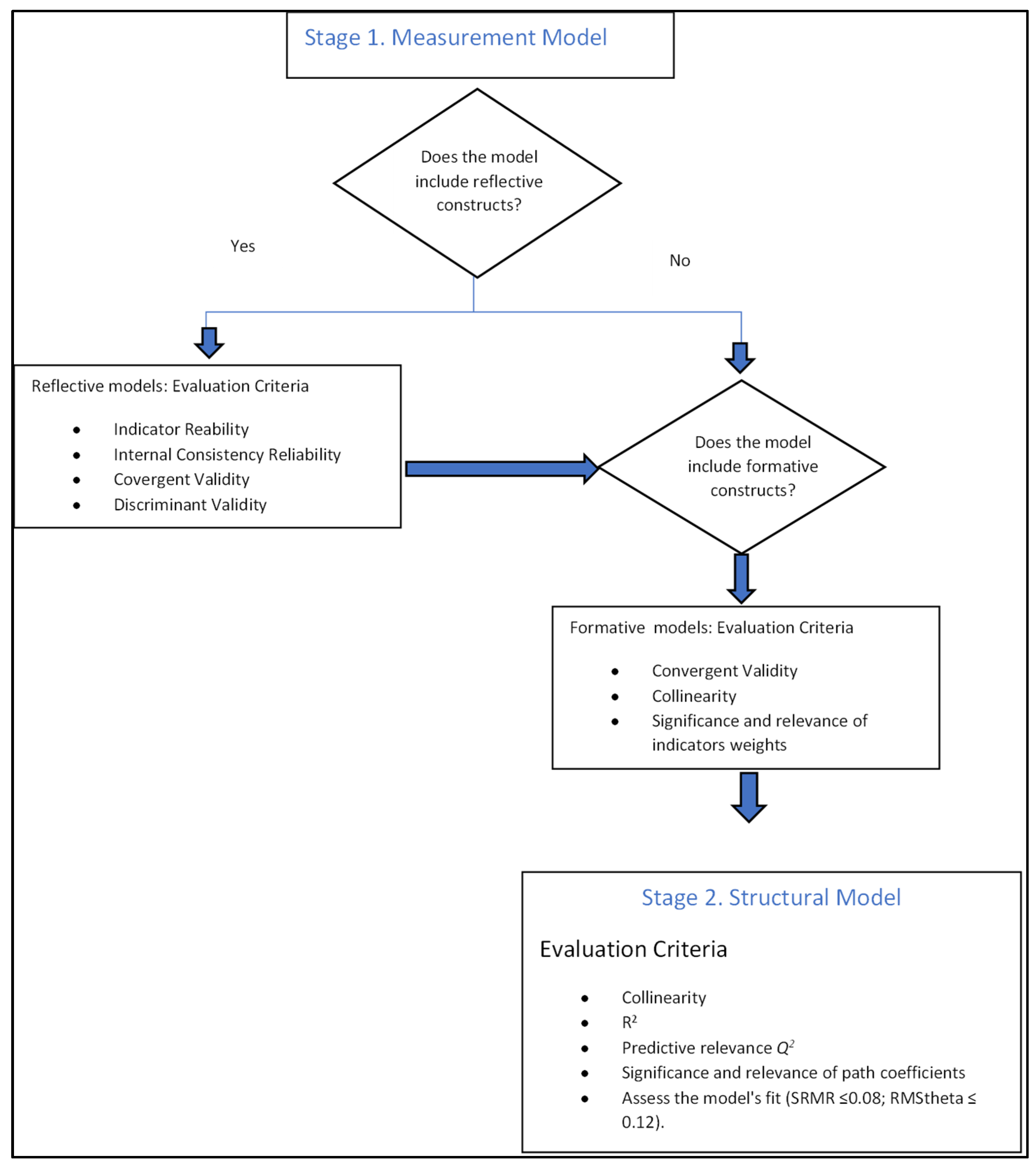

3.4. Research Method

- -

- Indicator Reliability: Outer loading for each indicator should meet or exceed 0.70 (Lowry & Gaskin, 2014).

- -

- Internal Consistency Reliability: Assessed using Cronbach’s alpha (α) and Composite Reliability (CR), with a threshold of ≥ 0.70 for both (Hair et al., 1998).

- -

- Validity:

- Convergent Validity: Average variance extracted (AVE) should be ≥ 0.50 (Hair et al., 2017).

- Discriminant Validity: Verified by three methods:

- ○

- Fornell–Larcker criterion (Hair et al., 2017);

- ○

- Cross-loadings; (Hair et al., 1998);

- ○

- Heterotrait-monotrait ratio (HTMT) (Hair et al., 2017).

- -

- Check for collinearity issues (VIF < 5);

- -

- Evaluate the significance and relevance of the relations in the structural model (p < 0.05);

- -

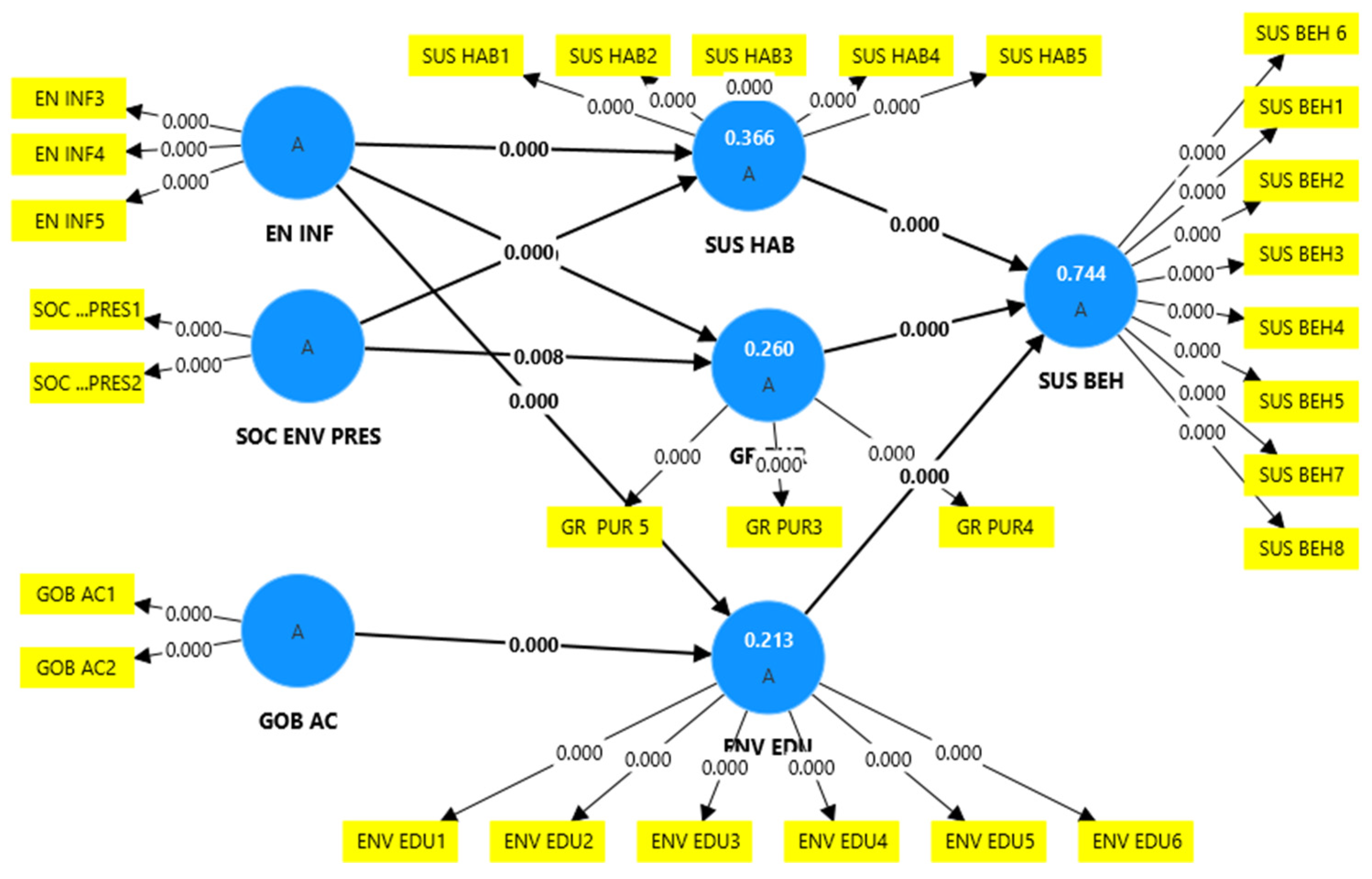

- Analyze the R2 level (with thresholds of 0.190 for weak, 0.333 for moderate and 0.670 for substantial);

- -

- Assess Q2 values (should be over zero);

- -

- Check the model’s fit (SRMR ≤ 0.08; RMStheta ≤ 0.12).

4. Results

4.1. Measurement Model

- -

- Internal Consistency Reliability Tests

- -

- Discriminant Validity

4.2. Structural Model Validation

- -

- The Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR). In this study, the SRMR was 0.082, which is below the threshold of 0.10 recommended by (Lohmöller, 1989).

- -

- The Normed Fit Index (NFI), as proposed by (Chin & Newsted, 1999). Higher values close to 1 indicate a better fit, with values above 0.9 representing an acceptable fit level (Lohmöller, 1989; Hu & Bentler, 1999). Here, the NFI value was 0.658.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AVE | Average variance extracted |

| CB-SEM | Covariance-based and structural equation modeling |

| CFA | Confirmatory Analysis |

| CR | Composite Reliability |

| GoF | Goodness of fit |

| HTMT | Heterotrait–monotrait ratio |

| PLS | Partial Least Square |

| Sustainability | 2022, 14, 13261 20 of 28 |

| PLS-SEM | Partial Least Square and structural equation model |

| Q2 | Goodness of PLS prediction |

| QoI | Quality of Interaction |

| R2 | Determination Coefficient |

| RMS | Root Mean Square |

| SRMR | Standardized Root Mean Residual |

| VIF | Variance inflation factor |

| SUS BEH | Sustainable Behavior |

| SUS HAB | Sustainable Habits |

| GR PURCH | Green Purchase |

| ENV EDU | Environmental Education and Information |

| ENV INF | Environmental Influence |

| SOC ENV PR | Social Environmental Pressure |

| GOB AC | Government Action |

Appendix A

| EN INF | ENV EDU | GOB AC | GR PUR | SOC ENV PRES | SUS BEH | SUS HAB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EN INF | 0.793 | ||||||

| ENV EDU | 0.354 | 0.719 | |||||

| GOB AC | 0.210 | 0.364 | 0.810 | ||||

| GR PUR | 0.484 | 0.473 | 0.219 | 0.789 | |||

| SOC ENV PRES | 0.238 | 0.225 | 0.209 | 0.272 | 0.834 | ||

| SUS BEH | 0.538 | 0.566 | 0.275 | 0.774 | 0.228 | 0.747 | |

| SUS HAB | 0.563 | 0.426 | 0.257 | 0.670 | 0.349 | 0.770 | 0.721 |

| VIF | |

|---|---|

| EN INF3 | 1.349 |

| EN INF4 | 1.466 |

| EN INF5 | 1.433 |

| ENV EDU1 | 1.346 |

| ENV EDU2 | 1.765 |

| ENV EDU3 | 1.809 |

| ENV EDU4 | 2.128 |

| ENV EDU5 | 1.669 |

| ENV EDU6 | 1.914 |

| GOB AC1 | 1.121 |

| GOB AC2 | 1.121 |

| GR PUR 5 | 1.346 |

| GR PUR3 | 1.341 |

| GR PUR4 | 1.453 |

| SOC ENV PRES1 | 1.272 |

| SOC ENV PRES2 | 1.272 |

| SUS BEH 6 | 1.920 |

| SUS BEH1 | 1.668 |

| SUS BEH2 | 2.927 |

| SUS BEH3 | 1.915 |

| SUS BEH4 | 2.367 |

| SUS BEH5 | 2.246 |

| SUS BEH7 | 1.930 |

| SUS BEH8 | 1.579 |

| SUS HAB1 | 1.687 |

| SUS HAB2 | 1.381 |

| SUS HAB3 | 1.205 |

| SUS HAB4 | 1.819 |

| SUS HAB5 | 1.457 |

References

- Ajzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behaviour. In J. Kuhl, & J. Beckmann (Eds.), Action control: From cognition to behaviour (pp. 11–39). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance tests and goodness of fit in the analysis of covariance structure. Psychological Bulletin, 88, 588–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caeiro, S., Ramos, T. B., & Huisingh, D. (2012). Procedures and criteria to develop and evaluate household sustainable consumption indicators. Journal of Cleaner Production, 22, 72–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, L. (2007). Childhood experiences associated with care for the naturalworld: A theoretical framework for empirical results. Children, Youth and Environments, 17, 144–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M. F., & Tung, P. J. (2010). The moderating effect of perceived lack of facilities on consumers’ recycling intentions. Environment and Behavior, 42(6), 824–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, W. W., & Newsted, P. R. (1999). Structural equation modeling analysis with small samples using partial least squares. In R. Hoyle (Ed.), Statistical strategies for small samples research (pp. 307–341). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Corral-Verdugo, V. (2012). The positive psychology of sustainability. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 14(5), 651–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amato, D., Korhonen, J., & Toppinen, A. (2019). Circular, green, and bioeconomy: How do companies in land-use intensive sectors align with sustainability concepts? Ecological Economics, 158, 116–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do Paco, A., Shiel, C., & Alves, H. (2019). A new model for testing green consumer behaviour. Journal of Cleaner Production, 207, 998–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagles, P. F. J., & Demare, R. (1999). Factors influencing children’s environmental attitudes. The Journal of Environmental Education, 30, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Figueroa-García, E. C., García-Machado, J. J., & Perez-Bustamante Yabar, D. C. (2018). Modeling the social factors that determine sustainable consumption behavior in the community of Madrid. Sustainability, 10(8), 2811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, D., Böhme, T., & Geiger, S. M. (2017). Measuring young consumers’ sustainable consumption behavior: Development and validation of the YCSCB scale. Young Consumers, 18, 312–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention, and behaviour: An introduction to theory and research. Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, T., Schlange, J., & Cort, T. (2020). Report of results global survey on sustainability and the SDGs. Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety. Available online: https://www.globalsurvey-sdgs.com/ (accessed on 13 July 2024).

- Gleim, M., Smith, J., Andrews, D., & Cronin, J. J., Jr. (2013). Against the green: A multi-method examination of the barriers to green consumption. Journal of Retailing, 89, 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S., & Ogden, D. T. (2009). To buy or not to buy? A social dilemma perspective on green buying. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 26, 376–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis (5th ed.). Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Hult, G. T. M., Ringle, C., & Sarstedt, M. A. (2017). Primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) (2nd ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M., & Ringle, C. M. (2019). When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. European Business Review, 31(1), 2–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajer, M., Nilsson, M., Raworth, K., Bakker, P., Berkhout, F., de Boer, Y., Rockstr€om, J., Ludwig, K., & Kok, M. (2015). Beyond cockpit-ism: Four insights to enhance the transformative potential of the sustainable development goals. Sustainability, 7(2), 1651–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.-T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollmuss, A., & Agyeman, J. (2002). Mind the Gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environmental Education Research, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalska, A., Ratajczyk, M., Manning, L., Bieniek, M., & Macik, R. (2021). Young and green: A study of consumer’ perceptions and reported purchasing behaviour towards organic food in poland and the United Kingdom. Sustainability, 13, 13022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiva-Brondo, M., Lajara-Camilleri, N., Vidal-Meló, A., Atarés, A., & Lull, C. (2022). Spanish university students’ awareness and perception of sustainable development goals and sustainability literacy. Sustainability, 14, 4552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohmöller, J. B. (1989). Predictive vs. structural modeling: Pls vs. ml. In Latent variable path modeling with partial least squares (pp. 199–226). Physica. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowry, P. B., & Gaskin, J. (2014). Partial least squares (PLS) structural equation modeling (SEM) for building and testing behavioral causal theory: When to choose it and how to use it. IEEE Transactions on Dependable and Secure Computing, 57, 123–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Acosta, M., Vázquez-Villegas, P., Mejía-Manzano, L. A., Soto-Inzunza, G. V., Ruiz-Aguilar, K. M., Kuhn Cuellar, L., Caratozzolo, P., & Membrillo-Hernández, J. (2023). The implementation of SDG12 in and from higher education institutions: Universities as laboratories for generating sustainable cities. Frontiers in Sustainable Cities, 5, 1158464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachs, J. D. (2012). From millennium development goals to sustainable development goals. The Lancet, 379, 2206–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salgado Beltrán, L., & Bravo Díaz, B. (2015). Consumo verde en el norte de sonora. Agroproductividad, 8, 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, J., Taisch, M., & Mier, M. O. (2017). Influencing factors to facilitate sustainable consumption: From the expert’s viewpoints. Journal of Cleaner Production, 142, 203–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L., & Gifford, R. (2005). Sustainable transport and quality of life. Journal of Transport Geography, 13, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straughan, R. D., & Roberts, J. A. (1999). Environmental segmentation alternatives: A look at green consumer behavior in the new millennium. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 16, 558–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabernero, C., Hernández, B., Cuadrado, E., Luque, B., & Pereira, C. R. (2015). A multilevel perspective to explain recycling behaviour in communities. Journal of Environmental Management, 159, 192–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeneke, A. (2019). Global survey shows 74% are aware of the sustainable development goals. World Economic Forum. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/press/2019/09/global-survey-shows-74-are-aware-of-the-sustainable-development-goals/ (accessed on 20 September 2024).

- United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. General Assembly of the United Nations. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_70_1_E.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2024).

- United Nations. (2023). The sustainable development goals report: Special edition. Available online: https://desapublications.un.org/publications/sustainable-development-goals-report-2023-special-edition (accessed on 28 December 2024).

- Vicente-Molina, M. A., Fernández-Sáinz, A., & Izagirre-Olaizola, J. (2013). Environmental knowledge and other variables affecting pro-environmental behaviour: Comparison of university students from emerging and advanced countries. Journal of Cleaner Production, 61, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wetzels, M., Odekerken-Schroder, G., & Van Oppen, C. (2009). Using PLS path modeling for assessing hierarchical construct models: Guidelines and empirical illustration. MIS Quarterly, 33(1), 177–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yli-Panula, E., Jeronen, E., & Rodriguez-Aflecht, G. (2020). Nature is something we can’t replace: Mexican students’ views of the landscape they want to conserve. Education Sciences, 10, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Indicator | % | |

|---|---|---|

| GD_1 | Between 18 and 24 years | 81.12 |

| Between 25 and 30 years | 7.65 | |

| Over 30 years | 6.63 | |

| NS/NC | 4.59 | |

| GD_2 | Degree | 81.12 |

| Master | 18.36 | |

| Doctorate | 0.51 | |

| GD_3 | Female | 51.53 |

| Male | 47.95 | |

| NS/NC | 0.51 |

| Indicator | Definition |

|---|---|

| General data (GD) | |

| GD_1 | Age |

| GD_2 | Level of education |

| GD_3 | Gender |

| Sustainable Consumption Habits (SUS HAB) | |

| SUS HAB 1 | Every day I am careful about the activities I perform to protect the environment. |

| SUS HAB_2 | I perform specific activities to protect the environment. |

| SUS HAB_3 | I consume local products to support the economy of my area |

| SUS HAB_4 | I consider myself environmentally responsible. |

| SUS HAB_5 | I consider the potential environmental impact of my actions before making decisions. |

| Sustainable Consumption Behavior (SUS BEH) | |

| SUS BEH_1 | It is important for me that the products I consume do not harm the environment. |

| SUS BEH_2 | I am motivated to make changes in my lifestyle to achieve responsible consumption. |

| SUS BEH_3 | I care about wasting our planet’s resources. |

| SUS BEH_4 | I would describe myself as an environmentally responsible and involved person. |

| SUS BEH_5 | I am willing to compromise my comfort to act in an environmentally responsible way. |

| SUS BEH_6 | I try to buy products that do not have too much packaging. |

| SUS BEH_7 | If possible, I buy products in reusable/recyclable packaging. |

| SUS BEH_8 | I have convinced my family and/or friends to buy responsibly. |

| Environmental Influence (ENV INF) | |

| ENV INF_1 | Someone in my family or friends motivates me to be environmentally friendly. |

| ENV INF_2 | I have volunteered for social work related to the environment. |

| ENV INF_3 | Being environmentally friendly is a priority in my family. |

| ENV INF_4 | At my usual home, waste is separated for recycling. |

| ENV INF_5 | At my usual home, there are always green spaces. |

| Environmental Education and Information (ENV EDU) | |

| ENV EDU 1 | I have been taught activities to be more responsible in resources use (water, electricity, energy). |

| ENV EDU2 | I am informed about the environmental problems that currently exist. |

| ENV EDU3 | I am informed about the negative effects of certain products that I consume. |

| ENV EDU4 | I usually pay attention to environmental advertising. |

| ENV EDU5 | I am aware of the advertising behind organic products. |

| ENV EDU6 | The use of green messages in advertising affects my attitude about that advertising. |

| Social Environmental Pressure (SOC PR) | |

| SOC PR_1 | I have felt pressure from my friends to perform activities that benefit the environment. |

| SOC PR_2 | I feel obliged to belong to a group of people involved with the environment. |

| Green Purchase (GR PURCH) | |

| GR PUR 1 | I trust organic products more than conventional ones. |

| GR PUR 2 | I think there are many places where I can find products that are not harmful to the environment. |

| GR PUR 3 | I support brands that produce responsibly. |

| GR PUR 5 | I take advantage of the fact that I can now easily get products. |

| Government Action (GOB AC) | |

| GOB AC_1 | In my city, the government motivates people to act responsibly through equality and social justice. |

| GOB AC_2 | The government is responsible for doing what is necessary so I can take action in favor of the environment. |

| Cronbach’s Alpha | Composite Reliability (CR) | Average Variance Extracted (AVE) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| EN INF | 0.719 | 0.778 | 0.630 |

| ENV EDU | 0.812 | 0.822 | 0.517 |

| GOB AC | 0.495 | 0.560 | 0.656 |

| GR PUR | 0.703 | 0.762 | 0.623 |

| SOC ENV PRES | 0.632 | 1.124 | 0.696 |

| SUS BEH | 0.886 | 0.890 | 0.558 |

| SUS HAB | 0.763 | 0.782 | 0.520 |

| EN I NF | ENV EDU | GOB AC | GR PUR | SOC ENV PRES | SUS BEH | SUS HAB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EN INF | |||||||

| ENV EDU | 0.419 | ||||||

| GOB AC | 0.301 | 0.561 | |||||

| GR PUR | 0.616 | 0.603 | 0.344 | ||||

| SOC ENV PRES | 0.319 | 0.301 | 0.333 | 0.341 | |||

| SUS BEH | 0.626 | 0.655 | 0.390 | 0.949 | 0.270 | ||

| SUS HAB | 0.712 | 0.546 | 0.389 | 0.885 | 0.423 | 0.924 |

| Original Sample (O) | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T Statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p Values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EN INF -> ENV EDU | 0.291 | 0.296 | 0.068 | 4.281 | 0.000 |

| EN INF -> GR PUR | 0.445 | 0.447 | 0.061 | 7.341 | 0.000 |

| EN INF -> SUS HAB | 0.509 | 0.513 | 0.051 | 9.993 | 0.000 |

| ENV EDU -> SUS BEH | 0.199 | 0.203 | 0.044 | 4.535 | 0.000 |

| GOB AC -> ENV EDU | 0.303 | 0.309 | 0.065 | 4.639 | 0.000 |

| GR PUR -> SUS BEH | 0.400 | 0.400 | 0.053 | 7.489 | 0.000 |

| SOC ENV PRES -> GR PUR | 0.166 | 0.169 | 0.063 | 2.646 | 0.008 |

| SOC ENV PRES -> SUS HAB | 0.228 | 0.230 | 0.059 | 3.893 | 0.000 |

| SUS HAB -> SUS BEH | 0.417 | 0.415 | 0.050 | 8.310 | 0.000 |

| Q2 Predict | RMSE | MAE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ENV EDU | 0.181 | 0.911 | 0.703 |

| GR PUR | 0.235 | 0.884 | 0.710 |

| SUS BEH | 0.293 | 0.854 | 0.665 |

| SUS HAB | 0.349 | 0.818 | 0.645 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Martinez Gomez, M.; Alcaide Gonzalez, M.A.; de la Poza Plaza, E. Modeling the Factors That Determine Sustainable Development Goal 12 in University Students. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 325. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030325

Martinez Gomez M, Alcaide Gonzalez MA, de la Poza Plaza E. Modeling the Factors That Determine Sustainable Development Goal 12 in University Students. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(3):325. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030325

Chicago/Turabian StyleMartinez Gomez, Monica, Ma Angeles Alcaide Gonzalez, and Elena de la Poza Plaza. 2025. "Modeling the Factors That Determine Sustainable Development Goal 12 in University Students" Education Sciences 15, no. 3: 325. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030325

APA StyleMartinez Gomez, M., Alcaide Gonzalez, M. A., & de la Poza Plaza, E. (2025). Modeling the Factors That Determine Sustainable Development Goal 12 in University Students. Education Sciences, 15(3), 325. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030325