Abstract

This study examines the experiences of pre-service teachers (PSTs) participating in Australian state-and-territory-specific programs that address teacher workforce shortages in Australia. Using a multi-methods approach, data from surveys and interviews are used to explore the impact of these programs on PSTs’ academic outcomes, professional learning, and well-being. Situated learning theory underpins the analysis, emphasising communities of practice, legitimate peripheral participation, and self-identity development. The findings reveal significant benefits such as accelerated career growth, enhanced confidence, and the integration of theory and practice. Enablers include school mentorship, university flexibility, and financial compensation inclusive of paid teaching programs. However, challenges persist, including emotional and workload pressures, inconsistent mentorship, and ambiguous application processes. This study recommends improving policy implementation and support structures, advocating for streamlined application processes, strategic workload management, and enhanced mentorship. These findings could contribute to understanding the competing demands of PSTs and inform policy improvements for future educators.

1. Introduction

The Australian Government anticipates that from 2025, there will be over 4000 unfilled teaching positions across Australian states and territories (Australian Government Department of Education, 2023; Longmuir, 2024). In 2022, the Ministers for Education established a National Teacher Workforce Action Plan (NTWAP) to address teacher workforce issues, identifying five priority areas: improving teacher supply, strengthening initial teacher education (ITE), maintaining the current teaching workforce, elevating the profession, and building a better understanding of future workforce needs (Australian Government, 2023b). While the NTWAP was in development, the shortage of teachers, particularly in regional and remote locations, prompted the creation of new policies and practices to address the urgent need to fill these areas (Australian Government, 2023a).

Negotiations between teacher registration authorities, state and territory Departments of Education, and ITE providers have resulted in a range of policies and practices through which pre-service teachers (PSTs) can be employed in schools while continuing to complete their ITE degrees. New teacher registration regulations and policies, overseen by individual state-and-territory-based teacher registration authorities, have introduced or made adjustments to the following PST registration options: Conditional Accreditation (CA) in New South Wales (NSW) and Victoria (VIC), Restricted and Unrestricted Permit to Teach (RPTT and UPTT) in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT), and Special Authority to Teach (SAT) in South Australia (SA). This paper collectively refers to these as the ‘Early Teacher Registration Programs’ (ETRPs).

In South Australia, the Teachers Registration Board of South Australia (TRB SA) stated, “A Special Authorisation for an Unregistered Person to Teach is issued under section 30 of the Teachers Registration and Standards Act, 2004, being an emergency measure, restricted to ‘hard to fill school sites only’” (SA TRB, 2022, n.p.), also stating:

“The Board acknowledges that SAT holders who are also studying to be a teacher, must meet many challenges to complete their qualification whilst being employed during the period of holding a SAT. In effect, you seek to be employed with benefits of on-the job learning whilst still studying. This challenging situation is one not met by other preservice teachers (n.p.)”.

Other jurisdictions such as the ACT, under the remit of the Teacher Quality Institute (TQI), identify that “Permits to Teach may be approved, where there is not a registered teacher available to fill a position, for applicants who have specialist knowledge, training, skills or qualifications or whose teaching qualification does not meet the eligibility requirements for Full or Provisional registration” (TQI, 2023). In 2024, the ACT government expanded the Permit to Teach program to include NSW PSTs, with the Minister for Education stating that “Through the agreements we have in place with universities, we are ensuring the teachers of the future are getting experience in the classroom while also being paid for the work they do” and “Last year 61 ITE students registered for a Permit to Teach across ACT public schools, which was beneficial not only for them but also for our schools, who continue to face challenges due to the ongoing national teacher shortage” (ACT Government, 2024). While in NSW, the New South Wales Education Standards Authority (NESA) Proficient Teacher Accreditation Policy—states that “conditionally accredited teachers develop their practice at Proficient Teacher by participating in a range of professional activities while employed as a teacher in a school/s/service/s” (NSW Education Standards Authority, 2019). NESA also clearly stipulate that PSTs who are given conditional approval still need to complete and be awarded an accredited teaching degree within a specified timeframe (NSW Education Standards Authority, 2019). While ETRPs provided schools with opportunities to fill vacancies and PSTs with an opportunity to commence their careers earlier than initially anticipated, it was acknowledged that close attention to support for the PSTs would be required.

Policy documents issued by relevant state and territory education departments—such as the Australian Capital Territory Education Directorate (ACTED), Department for Education South Australia (DfE SA), Department of Education New South Wales (DoE NSW), and Department of Education Victoria (DoE VIC)—provide guidelines for implementing these programs and clarify the roles of specific employment bodies. For example, Catholic Education South Australia (n.d.) stated, “Schools play a pivotal role in assuring that the [SAT] holders are proficiently overseen, mentored, and adequately inducted, keeping child safety and well-being at the forefront. It is mandatory to designate a primary mentor for every SAT TRT holder” (n.p.). State and territory policies continue to evolve to address the dynamic challenges of teacher shortages, with each jurisdiction tailoring its framework to its unique context. A working example can be seen in the ACT Permit to Teach program, which has established formal agreements in place with multiple university providers to “ensure the teachers of the future are getting experience in the classroom while also being paid for the work they do” (ACT Government, 2024).

Universities are key stakeholders in the ETRPs, as they are accountable for ensuring PSTs meet accreditation requirements formally approved by state and territory registration authorities. Over 50% of Australian PSTs hold some form of part-time employment to support their study and living expenses (Beerkens et al., 2011); however, many universities maintain the expectation that course attendance and authentic academic engagement remain priorities over part-time work. Neyt et al. (2019) conducted a systematic review of the effects of work on PSTs’ academic progress and found that working more than 15 h per week had a negative impact on study progress while working fewer than 15 h could be beneficial. They did not specify whether the work related to education. Furthermore, Neyt et al. (2019) found that work-oriented PSTs performed worse academically compared to study-oriented PSTs.

Dekker et al. (2024) investigated the influence of unpaid internships (professional experience), paid work outside of education, and paid work as a teacher (prior to completing teaching qualifications) on the study progress of 132 PSTs in the Netherlands. They found that paid-domain-relevant work of between 8 and 24 h per week in the third and fourth years of a PST’s degree did not negatively affect their study progress. However, they noted that unpaid work required for course completion, such as professional experience, negatively impacted progress because PSTs needed to continue non-domain-specific work to maintain income. Dekker et al. (2024) concluded, “Getting paid for relevant work allows two benefits: learning on the job while allowing one to quit spending time on a non-relevant job that does not grant these benefits” (p. 24).

While research lends support for combining education-domain-related work with study, starting with teaching assistant work and progressing to autonomous teaching positions (Dekker et al., 2024; Neyt et al., 2019), a search of Australian universities’ websites provides limited evidence of any specific policies or practices supporting the ETRPs. From the experience of the authors of this paper, most universities tend to modify and adapt attendance requirements depending on individual needs. For example, after-hours online classes may be created for PSTs teaching in regional or remote areas or for those unable to attend due to teaching commitments. However, what has not changed is the expectation that PSTs complete all academic course requirements. PSTs are often the key communicators between their school and university, given the current lack of formal agreements between education departments, schools, and universities regarding recommendations for maximum teaching hours for PSTs and whether some university requirements could be met through school-based formally assessed work.

Australia has supported variations to the traditional university-based teaching qualifications, including programs such as Teach for Australia (2023), the Nexus Program (Australian Government, 2023b), and Australian internship models (Ledger & Vidovich, 2018), with these programs emphasising that experiential learning provides a valuable transition to the teaching profession and enhances the knowledge and skills of teaching graduates. Ledger and Vidovich (2018) highlighted variations in internship models, ranging from co-teaching to independent teaching. They also identified how teaching contexts and policies—encompassing philosophy, people, places, processes, and power—influence the experiences of PSTs. Furthermore, they argue that the area is “under-researched and under-utilised” (Ledger & Vidovich, 2018, p. 25).

While ETRPs require PSTs to teach independently, there are expectations they will also be mentored and well-supported by schools and universities. The implementation of the ETRPs offers a timely opportunity to research the lived experiences of PSTs, explore how they manage employment and study, and gather their recommendations for ongoing policy and practice improvements.

Situated learning theory (Lave & Wenger, 1991) has been identified as an ideal framework for investigating the role of authentic environments and the social interactions they bring to PSTs’ learning while employed in an ETRP. This study focuses on understanding how employment as a beginning teacher while concurrently completing an education degree presents both affordances and challenges. It also examines what experiences and resources, including key individuals, influence PSTs’ emerging professional identities.

2. Conceptual Framework: Situated Learning Theory

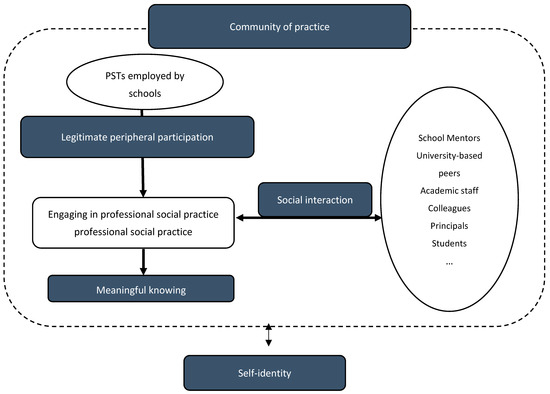

A community of practice (CoP) fosters learning and growth by bringing individuals together to share knowledge, experiences, and skills in a collaborative environment (Lave & Wenger, 1991). Situated learning theory (SLT) offers a comprehensive framework for understanding how learning happens naturally through engagement in authentic environments and social interactions. It emphasises the importance of participating in real-world activities that are socially and contextually embedded, as experienced by PSTs undertaking teaching roles while completing their education degrees (refer to Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework: situated learning theory in pre-service teacher programs.

CoP is a foundational element of SLT and serves as a prerequisite for its success. It emphasises a shared sense of belonging, values, and goals among members, enabling meaningful social and professional interactions (Lave, 2009). In the context of this study, PSTs were employed by schools where their CoP included other teachers, mentors, and students, which aligns with the recommendations of the Strong Beginnings Report (Department of Education, 2023). This environment facilitated opportunities for PSTs to engage in professional social practices, distinguishing this approach from other learning theories. However, the extent of CoP engagement varied. In some cases, PSTs were minimally introduced to the school environment, for example, through a single day of observation before starting their teaching duties, rather than being fully immersed in a robust CoP model.

Additionally, legitimate peripheral participation (LPP) is a key concept in SLT. It refers to the process by which newcomers begin at the periphery of a community—observing and learning from experienced members—before progressively taking on more active roles (Lave & Wenger, 1991). For some PSTs participating in this study, this process involved a gradual increase in teaching responsibilities, building confidence and competence. However, for others, opportunities for progressive involvement were limited due to varying school practices, such as minimal observation periods or insufficient mentoring support. This variation underscores that while LPP is an ideal model, its implementation depends on the school context and available resources.

Furthermore, social interaction is another critical element of SLT, underpinning all aspects of the CoP. Social interactions, including collaboration, dialogue, modelling, questioning, and negotiation, are fundamental to learning (Lave & Chaiklin, 1993); these interactions are fostered both in the university and school environments. However, in school environments, these interactions are related to concrete situations, often occurring in real-time and demanding action. Such authentic lived experiences are difficult to replicate in the university environment.

Meaningful knowing emerges as an outcome of SLT. It involves connecting theoretical knowledge to practical action in context-rich environments (Lave, 2009). Such opportunities arise when learning occurs in real-world situations, where understandings of pedagogy and classroom dynamics—often introduced in university settings—are applied. Lave (2009) also stresses the importance of reflection on practice. Time for such reflection can be supported by school-based CoPs and universities.

Development of self- and professional- identity is a central aspect of SLT. Lave and Wenger (1991) argue that identity evolves through increased participation in the CoP. PSTs engaging in ETRPs are assigned a mentor teacher, who plays a critical role in the induction of the PST to the school-based CoPs (often more than one in secondary schools). Kearney (2015) states that

“The beginning teacher starts their career on the periphery of the organisation because they do not have the domain knowledge to become part of an established learning community or community of practice; therefore, the induction process functions as an effective way for beginning teachers to collaborate with their more experienced colleagues and continue their professional learning by legitimately participating within that community (p. 7)”.

The quality of induction and the associated sense of belonging to the CoP can either enhance or diminish PSTs’ sense of beginning teacher professional identity (Kearney, 2015). However, in the current context of teacher shortages, the capacities for quality induction and mentoring may be at risk. This research provides an opportunity to explore PSTs’ school-based experiences and the influences on their sense of professional identity.

SLT provides a robust theoretical foundation for this research by highlighting how PSTs’ experiences are shaped by becoming members of a school-based CoP while continuing to engage with university-based peers and academic staff—another form of CoP, albeit varied in its focus. Figure 1 provides a visual representation of the conceptual framework, offering a foundation for the methodology that shaped this research.

Framed by new policy directions and the call for additional research on internships (Ledger & Vidovich, 2018), this research focuses on exploring the lived experiences of PSTs participating in the ACT, NSW, SA, and VIC Early Teacher Registration Programs while simultaneously pursuing their education degree. The research examines PSTs’ motivations for joining the ETRPs, the perceived benefits, the barriers and constraints they face, and the influence this experience has on their developing professional identity. Furthermore, this study seeks to identify recommendations for enhancing these ETRPs based on PSTs’ feedback.

By addressing the overarching research question, “how does engaging in paid teaching positions while studying impact the academic outcomes, sense of professional identity, and well-being of pre-service teachers?”, this research aims to shed light on the complex interplay between stakeholders’ roles in the ETRP initiative, designed to address teacher shortages in Australia.

3. Methods

3.1. Research Design

A multi-methods approach was employed to explore the perceptions of PSTs participating in ETRPs across the ACT, SA, NSW, and VIC. The study examined PSTs’ lived experiences, perceived benefits, enablers, and challenges. Quantitative data were collected through surveys to provide broad insights, while qualitative data from semi-structured interviews offered in-depth perspectives. The Flinders University Human Research Ethics Committee (ID: 5845) granted ethical approval for the study, with reciprocal ethics approvals being granted for interstate collaborators.

3.2. Participants

The study involved 126 PSTs employed under CA, PTT, RPTT, and SAT policies. Recruitment targeted PSTs from Government and Catholic schools through university email communications. Detailed participant information sheets outlined the study’s purpose, confidentiality measures, and informed consent procedures. Of the participants, 18 volunteered for semi-structured interviews to provide deeper qualitative insights into their experiences.

3.3. Data Collection

3.3.1. Survey

The survey, distributed via Qualtrics between August 2023 and December 2023, consisted of 48 questions divided into three parts:

Part A: Collection of demographic information, including participants’ state or territory or residence, university attended, degree level (early-year undergraduate, early-year postgraduate, primary undergraduate, primary postgraduate, secondary undergraduate, or secondary postgraduate), number of remaining topics in their education degree, employment fraction, and gender. These data provided contextual insights into the diverse profiles of PSTs.

Part B: This part included 41 Likert-scale items exploring participants’ reasons for joining the programs, experiences in the programs, and suggestions for improvement. Responses ranged from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” on a 5-point scale.

Part C: This part consisted of one open-ended question inviting participants to elaborate on their experiences and provide additional suggestions.

3.3.2. Semi-Structured Interviews

Overall, 18 interviews were conducted between October 2023 and May 2024, involving participants from Flinders University, Charles Sturt University, University of Canberra, and the Australian Catholic University. These interviews explored how PSTs integrated teaching responsibilities with academic studies and the supports or barriers they encountered. The interviews lasted 45–60 min and were audio-recorded with participant consent.

3.3.3. Delimitation

The study only includes PSTs who volunteered to participate in surveys and interviews, excluding perspectives from other stakeholders such as school leaders, mentors, and university staff. The findings reflect participants’ experiences between August 2023 and May 2024 and may not capture longer-term trends.

3.4. Data Analysis

3.4.1. Survey Data Analysis

Survey data were analysed using descriptive statistics in IBM SPSS v.29. Demographic data were summarised through frequency counts and percentages, while Likert-scale items were analysed for modes, means, standard deviations, and ranges. Preliminary data screening identified patterns, and missing data were addressed using pairwise deletion, allowing incomplete responses to be included in relevant analyses.

3.4.2. Thematic Analysis of Interview Data

Interview data were analysed using Clarke and Braun’s (2017) six-step thematic analysis framework. Researchers began by immersing themselves in the data through repeated readings of transcripts and taking initial notes to capture key expressions of participants’ experiences. Relevant excerpts were then coded to identify recurring concepts and patterns. Codes were collaboratively reviewed and refined by the research team to ensure reliability. Related codes were grouped into themes by examining similarities, differences, and relationships within the data. The themes were iteratively refined to maintain coherence and alignment with the study’s objectives. Final themes were defined and supported by illustrative quotes from participant responses to ensure an accurate representation of the data.

The final themes identified were as follows:

- Integration of theory and practice highlighting how PSTs applied academic knowledge in real-world classroom settings, enabling them to connect coursework with practical teaching experiences.

- Development of professional identity and confidence, emphasising the growth in teaching skills and self-efficacy as PSTs balanced their roles as students and educators.

- Enablers and supports, including mentorship, flexible university policies, and financial incentives, which helped PSTs manage work and study commitments effectively.

- Challenges included issues such as workload stress, role conflicts, and ambiguities in program policies, which impacted PSTs’ ability to navigate their dual responsibilities.

3.5. Limitations

The study heavily relied on self-reported survey responses and interviews, making it susceptible to biases such as social desirability and recall inaccuracies, which may limit objectivity. Additionally, the study provides a snapshot of experiences without longitudinal data, leaving a gap in understanding the long-term impacts on participants’ careers and growth. Selection bias is another concern, as participants who volunteered may have stronger or more polarised opinions compared to non-participants. Furthermore, differences in institutional and school support across states and universities are not fully controlled, potentially influencing the consistency of participants’ experiences and complicating cross-jurisdictional comparisons.

3.6. Rigour and Trustworthiness

To enhance rigour, themes were clearly defined and substantiated with participant quotes. Regular team consultations mitigated researcher bias and ensured diverse perspectives were incorporated. Triangulation of survey and interview findings enriched the overall interpretation of data, providing a comprehensive understanding of PSTs’ experiences.

4. Survey Findings

Of the 126 individuals who accessed the survey, 28 did not answer any questions and were therefore excluded from the analysis. The demographic data of the remaining 98 respondents are reported in Table 1. Participants from three states and one territory (a total of four universities) completed the survey. Most (71.4%, n = 70) identified as female, and nearly half (48%, n = 47) were secondary undergraduates, with one (22.4%, n = 22) or two (12.2%, n = 12) topics remaining in their degree. Most (88.8%, n = 87) reported employment fractions ranging from 0.2 to 1.0, with 0.6 (23%) being the most common.

Table 1.

Sample demographic characteristics.

The survey explored PSTs’ experiences with ETRPs’ employment and their education degree through 25 items covering overall feelings, perceived support, teaching challenges, role conflict, and impacts on daily life. Table 2 provides reasons why PSTs chose to work in employment-based teaching roles. The most common motivations included enhancing teaching skills and knowledge (M = 4.59, SD = 0.74), gaining a valuable start to their career (M = 4.77, SD = 0.5), and being directly approached by a placement school (M = 4.24, SD = 1.26). Participants reported generally positive experiences, with high mean scores for items related to confidence building and the integration of employment and studies, suggesting that most found the experience enriching and rewarding (Table 3).

Table 2.

Reasons for choosing to work as a SAT/CA/RPTT/UPTT/PTT pre-service teacher.

Table 3.

Experiences regarding SAT employment and completion of education degree.

Regarding support, participants highlighted school leadership, colleagues, and students as significant sources of encouragement, with high mean scores and mode values of 5 (Table 3). However, university support scored notably lower, with a mode of 2, indicating that many participants perceived limited flexibility and support from their institutions in accommodating their employment responsibilities (Table 3).

Teaching challenges, such as classroom management, lesson planning, assessment, and catering to diverse needs, received medium mean scores and mode values of 3 or 2 (Table 3). These results suggest that most participants found these challenges manageable, though the variability in responses (SD > 1) indicates that the degree of difficulty varied across individuals.

Role conflict emerged as a complex theme. Items related to additional school duties and stress from meeting school expectations had mode values of 5, reflecting significant agreement among participants about the strain these placed on their time and focus (Table 3). In contrast, items about quitting or taking a break from university had mode values of 1, suggesting these were less common concerns (Table 3). Other items, such as difficulty connecting with university colleagues and managing expectations, had mixed responses, reflecting diverse experiences (Table 3).

Finally, the impact on daily life was evident, with most participants agreeing that university tasks were completed outside school hours, as reflected in high mean scores with low variability (Table 3). Other aspects, such as effects on sleep, exercise, and social life, showed medium mean scores and higher variability, indicating diverse perceptions and experiences among participants (Table 3). Overall, the survey highlighted both the challenges and opportunities associated with balancing ETRP employment and education.

Participants rated seven recommendations for improving their ETRPs experience (Table 4). Academic credit recognition (M = 4.74, SD = 0.6; M = 4.7, SD = 0.79), university support (M = 4.33, SD = 1.04), and intensive course delivery (M = 4.31, SD = 0.99) received high mean scores with low variability, indicating strong agreement. Recommendations for reducing the final year course load (M = 3.96, SD = 1.25), reducing teaching workload (M = 3.23, SD = 1.4), and increasing employer support (M = 3.54, SD = 1.36) showed moderate agreement but greater variability, suggesting differing opinions among subgroups and the need for further exploration.

Table 4.

Recommendations.

5. Interview Findings

This study draws on a multi-methods approach, integrating survey data with semi-structured interviews conducted with 18 PSTs—eight males and ten females aged between their 20s and 40s—who are participating in ETRPs across the ACT, NSW, SA, and VIC. Regarding participant distribution, three were from SA, three were from VIC, six were from ACT, and six were from NSW. Participants who volunteered for interviews following survey completion provided insights into their lived experiences. Pseudonyms have been used to protect their identities. The findings connect quantitative survey results with qualitative themes, offering a comprehensive understanding of PSTs’ motivations, challenges, and professional development within these programs.

Grounded in SLT, this study examines how PSTs navigate their dual roles as students and teachers, particularly through their involvement in school-based CoPs. The analysis highlights how authentic learning environments, supported by mentorship and collaborative engagement, contribute to professional identity development and career readiness. The themes explored in the findings include the integration of theory and practice, professional growth, enablers and barriers within the programs, and their connections to survey results.

5.1. Benefits of the Programs

5.1.1. Application of Learning to the Classroom

PSTs in the ETRPs highlighted the value of integrating theory and practice through hands-on teaching. Lexi stressed the importance of classroom experience, stating, “There should be an opportunity to get into the classroom and teach”. Jen found that combining employment with studies made university concepts more intuitive, while Jack described the real-time application of knowledge as “extremely beneficial”, adding that “bringing theory and practice together is far more effective”. The survey results supported these experiences, with high ratings for confidence building (M = 4.64) and combining employment with studies (M = 3.91). This integration enriched learning and enhanced career prospects, as seen in Jack’s successful transition to a teaching position after completing the program. By bridging theory and practice, the ETRPs equip PSTs with the skills, knowledge, and confidence to transition to the role of graduate teacher.

5.1.2. Enhanced Professional Skill Development and Confidence

The ETRPs demonstrate the benefits of hands-on learning in teacher education, effectively bridging theory and practice. The survey findings reflect this, with high ratings for professional confidence (M = 4.64) and practical application (M = 4.59), supported by participants’ experiences. Clara described the ETRPs as an “apprenticeship model” that helped her refine her teaching skills while benefiting from “being paid to learn”. Ollie noted that hands-on experience tested theoretical knowledge, explaining, “Just because you get [a high distinction] doesn’t mean you’re going to be a perfect teacher”. Frank valued the opportunity to refine his practice and engage in meaningful discussions with peers and colleagues about best teaching practices, which he found more impactful than traditional academic tasks like essays. For some, the ETRPs also served as a “taste test” for exploring a teaching career, offering critical real-world insights. The ETRPs equip PSTs with the skills and readiness needed to succeed in their careers by fostering confidence and focusing on practical application.

5.2. Enablers of Success in the Programs

5.2.1. Support from Schools and Staff

A supportive school environment is essential for PSTs in the ETRPs, providing mentorship, professional development, and flexibility to balance their dual roles as students and teachers. Quantitative findings suggest this, with high ratings for school leadership support (M = 4.35) and colleague support (M = 4.36), indicating the significance of these elements in enabling PSTs to thrive. Carl’s experience highlights the importance of leadership support. He described his principal as “amazing” for offering flexibility and early career mentoring, which helped him navigate teaching and learning demands. Mei’s account underscores the value of inclusion in professional development, noting, “We’ve been included with the early career teachers… in all the full staff meetings”, which fostered her sense of belonging and professional growth. This suggests professional development opportunities are crucial in building PSTs’ confidence and competence. Mark’s story illustrates how school leaders’ flexibility supports PSTs in managing dual responsibilities. He recounted his principal’s reassurance: “If you ever need to not come in for a day… we will cover for you. Don’t even worry about that”. This understanding allows PSTs to meet their commitments without stress, enhancing their capacity to succeed in both roles. These experiences, alongside the quantitative findings, suggest that a supportive school environment—through leadership, mentorship, and inclusion—significantly contributes to PST confidence and success in the ETRPs. Together, these elements provide the stability and encouragement PSTs need to feel a sense of belonging within the school context and valued as a key member of staff.

5.2.2. Support from Universities

University support received lower ratings than school support in the survey, with a mean score of 2.84/5 and a mode of 2 from 69 respondents. This raised questions about the factors contributing to the gap between university and school support scores, prompting a closer examination of PSTs’ interviews. The findings revealed areas where university support could be improved to better align with PST needs. Shane highlighted the importance of a “really good foundation” provided by university tutors, noting their role in helping him navigate the overwhelming transition into teaching. However, he emphasised that more targeted foundational support was necessary. Similarly, Clara suggested universities should offer practical guidance on managing professional relationships, accessing policy documents, handling student and family issues, and maintaining personal well-being amid administrative demands. These reflections align with the survey results, suggesting tailored support and mentorship gaps. Flexibility in university scheduling emerged as a positive aspect for some PSTs. Rani acknowledged that the “support… has been endless”, particularly regarding flexible scheduling, which helped her manage her dual roles as a teacher and student. While this flexibility was appreciated, it does not negate the broader need for enhanced foundational and practical support identified by other participants.

5.2.3. Earning an Income

Involvement in the ETRPs provided PSTs with essential classroom experience and the significant advantage of financial compensation. In the survey, ‘earning an income’ scored a mean of 3.25/5, with the mode being 5, and while this was lower than ‘enhancing my skills and knowledge’ (4.59/5) and ‘a valuable start to my career’ (4.77/5), it still featured in the interview participants’ responses. This opportunity to earn an income served as both an incentive and a means to support themselves during their studies. Clara saw the ETRPs as a “good incentive” and appreciated being able to “work in the field [she] was running towards and earn a bit of money as well”. She emphasised that even the challenging experiences provided valuable insights: “you’re going to get an awesome experience. Even if they’re bad experiences, the job experience is invaluable”. Phil candidly expressed that financial gain was a primary reason for pursuing the ETRPs: “… so that I could work as a teacher and be paid”. Phil further emphasised the dual benefits: “… being able to get paid and working the job plus hopefully add to my further learning”. This suggests that the paid experience helps PSTs to explore their professional interests in a real-world context while providing monetary compensation. This sentiment encapsulates the unique advantage of being paid while learning, reinforcing the ETRPs’ role in providing financial relief and critical professional insights. This financial relief was seen as practical and essential for maintaining focus on their studies and completing their degrees, thereby effectively supporting participants in achieving their educational and professional goals.

5.2.4. Hybrid Learning Model

A hybrid model combining academic learning with practical classroom experience significantly benefits PSTs’ professional growth. Leah highlighted the value of having “her own classroom”, which allowed her to build relationships with students and apply theory-based strategies, deepening her “understanding and application of pedagogical concepts”. Despite challenges in balancing commitments, Jen noted that teaching responsibilities pushed her to produce lessons of a “higher standard” while maintaining Distinction grades in both semesters of 2023. These experiences demonstrate that, though demanding, the hybrid model effectively integrates theory with practice, enhancing professional growth and academic success.

5.2.5. Building Relationships and Community Connections

Building relationships within the community provides PSTs with essential support to navigate teaching complexities. Clara shared how “colleagues in my faculties have been generally really helpful… willing to lend a hand”, while Ollie emphasised the value of having a supportive mentor, describing his Assistant Principal as “very good at supporting me”. This mentorship offered him guidance and a safety net, highlighting the importance of leadership in nurturing PSTs. Fanny’s return to her hometown helped her build trust with students, observing that “the kids started coming to me for help more” as she developed positive relationships. Her experience suggests how familiarity with community fosters trust and deeper connections, enhancing teaching effectiveness. Regular meetings with school leaders also provided structured support, as Fanny recounted, "We used to have meetings like every four weeks… so much support came out of the unit." Brody appreciated learning from a diverse team, explaining that having “a good mix of new educators with experienced ones … really helps”, as listening to their experiences solidified his sense of belonging and professional growth. Strong relationships within the school, shared values, and consistent support are crucial for PSTs. Schools that encourage collaboration, mentorship and connections with the broader community create a nurturing environment where PSTs can thrive.

5.3. Challenges Faced in the Programs

5.3.1. Emotional and Workload Pressures

PSTs in ETRPs reported facing considerable challenges related to emotional intensity and workload demands. Survey data reflect these concerns, with stress from school expectations scoring high (M = 3.7) and workload reduction identified as an area for improvement (M = 3.23). These findings highlight PSTs’ difficulty in managing teaching responsibilities alongside academic commitments. Carl spoke to the emotional toll of teaching, admitting, “I didn’t know how emotionally draining it would be”, as he navigated the demands of lesson planning and managing student needs. Phil added to this, describing how balancing reports, planning, and university assignments felt “overwhelming” at times. These experiences reflect the tension between professional expectations and academic pressures. Lexi suggested part-time teaching as a solution for those struggling with full-time commitments, emphasising that understanding one’s capacity is essential to avoid burnout. Her perspective aligns with survey data, reinforcing the importance of workload flexibility in supporting PSTs. The combination of quantitative and qualitative findings suggests that the emotional and workload pressures of teaching stem from role conflict and the unexpected intensity of the profession. Addressing these challenges through targeted support and workload adjustments may support PSTs’ well-being and professional growth.

5.3.2. Navigating the Application Process

The lack of clear guidelines and structured onboarding emerged as a significant challenge for PSTs. Survey findings suggest inconsistencies in participants’ experiences, with variability in responses (SD > 1) and a mean score of 4.33, highlighting the need for improved institutional support. Phil described the process as “very confusing”, suggesting a lack of clear communication and support, aligning with the inconsistencies in the survey data. Frank similarly criticised the process as “messy” and time-consuming, reinforcing the need for greater clarity and efficiency. Leah emphasised the importance of structured onboarding, recommending “at least two days of administration and observation” to ease the transition into teaching rather than being “thrown into a class an hour into being there”. These findings suggest a shared need for transparency, consistency, and structured onboarding to address the frustrations and uncertainties PSTs face during the application process. Clear guidelines and enhanced institutional support can be critical in helping PSTs transition more confidently into professional teaching roles.

5.3.3. Lack of Mentorship and Support Structures

A significant challenge for PSTs in the ETRPs is the inconsistency in mentorship and support. Phil noted that promised support often failed to materialise, particularly in understaffed schools. Leah described feeling isolated due to minimal faculty interaction and limited access to necessary systems, stating, “I was pretty much on my own when it came to a lot of stuff”, despite organising her own check-ins with her SLC (School Leader C—Head of Department or Year Level Coordinator). Pat highlighted the contrasting experiences among colleagues, with one peer facing punitive responses to mistakes, while he benefited from a supportive mentor. These accounts highlight the pivotal role of structured and effective mentoring in helping PSTs navigate their teaching journey.

5.3.4. Extra Workload and Time Management Challenges

Managing full-time work, studies, and personal responsibilities proved overwhelming for many PSTs. Carl faced delays in completing his degree, citing difficulties in managing work, study, and family responsibilities: “… working full time and trying to study and my daughter was 12 at the time… are tricky [to] time manage”. Phil struggled with increased teaching loads without receiving his entitled release days, while Leah advised against heavy workloads, stating, “I wouldn’t recommend [a heavy workload] to another pre-service teacher”. Jen highlighted additional complexities in part-time roles, such as preparing detailed lesson plans for relief teachers, which added to her workload. She also expressed frustration with the system’s inflexibility, which prevented her from using relevant teaching evidence to demonstrate Graduate Standards. These experiences highlight the challenges PSTs face in balancing multiple responsibilities and emphasise the need for improved flexibility and support within the programs.

6. Discussion

The ETRPs offer a unique solution to Australia’s growing teacher workforce shortages while presenting significant opportunities and challenges for PSTs. This study’s findings, grounded in SLT (Lave & Wenger, 1991), demonstrate that PSTs gain invaluable real-world teaching experience, integrate theoretical knowledge with practice, and accelerate their professional growth. However, these benefits are tempered by emotional pressures, inconsistent support structures, and workload challenges that must be addressed to realise ETRPs’ potential fully. By situating PSTs within authentic school-based COPs, the ETRPs allow them to participate meaningfully in the teaching profession while still completing their degrees. This discussion connects the study’s findings to the broader body of research on teacher education, highlighting the dynamic interplay between benefits, enablers, and challenges as PSTs navigate these programs.

6.1. Integration of Theory and Practice

A key benefit of the ETRPs is the opportunity to bridge the often-cited gap between theory and practice in teacher education. Participants consistently highlighted how teaching while studying allowed them to strengthen their understanding of pedagogical concepts and apply them in real-world settings. This simultaneous engagement with academic learning and practical experience ensured that theoretical knowledge was not compartmentalised but actively informed classroom practices. Such alignment between coursework and teaching responsibilities supports findings from Darling-Hammond (2015), Zeichner (2010), and Williams and Sembiante (2022), who emphasise the importance of integrated teacher preparation programs (Opoku et al., 2020). Our survey results further support this integration, with high ratings for confidence building (M = 4.64) and the value of combining employment with studies (M = 3.91). This real-time application of knowledge ensures that PSTs gain a comprehensive understanding of the complexities of teaching, enabling them to refine their skills and transition seamlessly into full-time roles. By fostering practical engagement, the ETRPs address critical gaps in traditional teacher education programs and better prepare PSTs for the demands of the profession (Darling-Hammond et al., 2017; Ronfeldt et al., 2014).

6.2. Professional Identity Development and Confidence

The findings demonstrate that the ETRPs significantly contribute to PSTs’ professional identity and confidence. Participants noted that their involvement in the ETRPs led to faster career progression and a more defined sense of their professional roles. Practical teaching experiences embedded in the ETRPs allow PSTs to navigate the complexities of the teaching profession early in their careers, positioning them to seize professional opportunities with greater confidence and self-assurance (Power et al., 2023; Ronfeldt et al., 2014). These hands-on experiences not only enhance pedagogical skills but also foster self-efficacy, aligning with broader research that underscores the value of field-based learning in teacher preparation (Singha et al., 2024). This aligns with SLT, which suggests that legitimate peripheral participation enables PSTs to transition from observing to fully engaging in professional communities (Lave & Wenger, 1991). The ETRPs provide a structured pathway for PSTs to develop their professional identity through hands-on immersion in authentic teaching environments. Kolb’s (2014) experiential learning theory further supports this by emphasising that learning through real-world engagement strengthens both practical skills and conceptual understanding. These theoretical perspectives reinforce the study’s findings, illustrating how PSTs benefit from the dual emphasis on practical application and professional development within the ETRPs.

6.3. Supportive School Environments

Supportive school environments emerged as a critical enabler for PSTs’ success, as survey results demonstrated strong ratings for school leadership support (M = 4.35) and colleague support (M = 4.36). These findings highlight the importance of nurturing spaces where PSTs can access mentorship, guidance, and inclusion, which are vital for their professional growth. Participants described how principals and mentors played pivotal roles in fostering flexibility, encouragement, and access to professional development opportunities. Inclusion in early career development programs further reinforced their sense of belonging, while leadership flexibility was particularly appreciated in helping PSTs balance their dual roles as students and teachers. These findings are consistent with Chalies et al. (2021), who assert that effective mentoring enhances teaching competence and confidence among PSTs. Schools that prioritise mentorship and collaboration create CoPs that enable PSTs to thrive. However, challenges remain, as inconsistencies in mentorship and support structures were noted, particularly in under-resourced schools. This aligns with Hudson’s (2013) argument that structured mentoring programs are essential for ensuring equitable and effective support for all PSTs. Addressing these gaps is critical to maximising the benefits of supportive school environments and fostering professional success among PSTs.

6.4. University Support and Hybrid Learning Models

While schools emerged as critical sources of support, survey findings revealed a gap in university support, with lower ratings (M = 2.84) compared to school-based support. Participants acknowledged some positive aspects, such as flexible scheduling, but identified a need for more practical guidance and tailored support. Clara emphasised the need for universities to provide targeted support in managing professional relationships, administrative responsibilities, and personal well-being, aligning with findings by Murphy et al. (2024). The hybrid learning model—combining academic coursework with practical teaching—is a defining feature of the ETRPs. This model mirrors the practice-based learning approaches described by Darling-Hammond et al. (2017), who emphasise the importance of applying theoretical knowledge in real-world contexts. However, balancing these commitments remains a significant challenge, as reflected in workload-related survey scores (M = 3.23) and role conflict (M = 3.70). Such challenges align with Neyt et al. (2019), who highlighted that PSTs balancing work and study face greater strain without institutional coordination. Effective implementation of hybrid models requires closer collaboration between universities and schools to ensure manageable workloads and realistic expectations for PSTs (Dekker et al., 2024).

6.5. Fostering Professional Belonging

The findings of this study underscore the critical role of strong relationships within schools and communities as enablers of PSTs’ success. Survey responses and interviews revealed that supportive mentors, colleagues, and school leaders provided essential guidance, trust, and constructive feedback, facilitating professional growth and a sense of belonging. For instance, participants described how building trust with students and collaborating with experienced educators helped them navigate the complexities of teaching while fostering confidence in their abilities. Bjorklund et al. (2021), also highlight that trust and collaboration within CoPs positively influence PST confidence and resilience. Meaningful engagement with colleagues and mentors helps PSTs transition from peripheral participation to full involvement in their professional communities, as outlined by Lave and Wenger’s (1991) SLT. This framework emphasises the importance of social connections in developing professional competence and identity. Similarly, participants noted that being included in early career development sessions or benefiting from leadership flexibility helped them feel valued and supported in their dual roles, further reinforcing these theoretical principles. However, the strength of these relationships was not universal. The findings revealed that while some PSTs thrived within collaborative environments, others experienced inconsistencies in mentorship and a lack of meaningful engagement, particularly in schools with limited resources. This variation suggests that fostering strong school–community ties requires deliberate effort and structured support systems to ensure equitable access to mentorship and collaboration for all PSTs (Chalies et al., 2021; Hudson, 2013). By prioritising these efforts, schools can create a nurturing environment where PSTs grow professionally and develop a sustained commitment to the teaching profession.

6.6. Challenges: Emotional Pressures, Workload, and Onboarding

While the ETRPs provide valuable opportunities for professional growth, they also present significant challenges, particularly regarding emotional strain, workload demands, and unclear onboarding processes. Survey data revealed elevated stress levels due to role expectations (M = 3.70), with participants describing the emotional burden of managing teaching responsibilities alongside academic commitments. This balancing act highlights the toll of these dual roles, consistent with Jennings (2020), who argues that teaching’s inherent emotional intensity frequently results in burnout without adequate support structures. The findings of Neyt et al. (2019) further corroborate this, indicating that excessive working hours—even in domain-relevant employment—can negatively impact academic outcomes and overall well-being. Participants’ experiences highlighted the complexity of these challenges. Emotional exhaustion was commonly reported as PSTs juggled the competing demands of planning lessons, managing classrooms, and completing university assignments. In this context, the absence of robust support systems exacerbates these pressures, undermining PSTs’ capacity to succeed in both academic and professional settings.

Workload pressures were another frequently cited concern. Despite the flexibility afforded by some schools, survey findings and participant narratives indicated that the expectation to excel simultaneously in teaching and academic responsibilities was overwhelming. Dekker et al. (2024) argue that while employment in education-related roles can provide valuable experience, inadequate workload management significantly undermines progress and learning outcomes. PSTs frequently noted the need for realistic workload expectations to maintain their well-being and effectiveness in both domains. Moreover, the onboarding process—critical for easing transitions into teaching roles—emerged as another significant challenge. Participants described the onboarding experience as inconsistent and poorly communicated, creating unnecessary stress and confusion. Edwards et al. (2022) emphasise that well-structured induction processes are essential for fostering confidence and competence in PSTs. Without clear and consistent onboarding practices, PSTs risk feeling unprepared and unsupported, further compounding the pressures associated with their roles.

Addressing these challenges necessitates systemic changes. Strategies such as providing targeted mentoring, implementing realistic workload policies, and ensuring streamlined onboarding processes are essential for mitigating emotional and professional pressures. In addition, it may be timely to consider policies used in other industries, such as recognition for prior learning (RPL), whereby universities and accreditation bodies acknowledge the learning occurring for PSTs through their school-based employment and associated professional development as equivalent to course topics. By prioritising these measures, the ETRPs can create a more supportive environment that enhances PSTs’ professional growth, reduces workload pressures, and safeguards their well-being.

7. Conclusions

The ETRPs represent an innovative response to the dual challenges of increasing demand for qualified teachers and the importance of ensuring high-quality and authentic ITE for PSTs. However, while these programs offer significant opportunities, they also bring considerable challenges that must be addressed to maximise their potential impact. The ETRPs demonstrate the value of integrating theory and practice, allowing PSTs to gain real-world teaching experience while completing their studies. This dual approach is consistent with established educational theories, such as SLT, which emphasises the importance of learning in authentic environments. By creating opportunities for PSTs to engage in meaningful teaching experiences, the ETRPs enable participants to develop their professional identity, build confidence, and refine their teaching skills in preparation for full-time roles.

Simultaneously, this study reveals challenges that can hinder the success of ETRPs. Participants commonly cited emotional strain, workload pressures, and unclear onboarding processes as barriers to balancing their teaching and academic responsibilities. The findings indicate the need for targeted institutional support, realistic workload management, and transparent onboarding procedures to help PSTs navigate these dual roles effectively. High-quality mentorship also emerged as a critical factor, with structured mentoring programs providing much-needed guidance and support, contributing to professional growth and readiness.

The insights gained from this research provide a roadmap for improving ITE programs. Collaboration between universities, schools, and policymakers is crucial to align institutional expectations, streamline processes, and enhance support systems for PSTs. Tailored solutions, such as improved mentoring structures, flexible scheduling, reflective practices, and recognition of school-based learning, can create a more equitable and manageable pathway for PSTs to succeed in their studies and teaching roles. The implications of this study extend beyond the ETRPs, offering valuable lessons for the broader field of teacher education. As Australia seeks to address its teacher workforce shortages, the lived experiences of PSTs participating in these programs illuminate actionable strategies for supporting career readiness, retention, and long-term professional development. Future research should explore the longitudinal impacts of these programs, examining how early teaching experiences influence PSTs’ career trajectories, effectiveness in the classroom, and student outcomes. Additionally, incorporating the perspectives of mentors, school leaders, and policymakers would deepen the understanding of how systemic changes can enhance teacher preparation.

In conclusion, the ETRPs have the potential to transform teacher education by effectively bridging gaps between theory and practice while addressing immediate workforce needs. By acting on the recommendations presented, educational providers and policymakers can build a more sustainable and supportive framework for PSTs, ensuring that ETRPs prepare confident, skilled, and adaptable educators ready to meet the challenges of the teaching profession in a dynamic educational landscape.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.B.R., L.B.-F., K.B., C.M., M.W., K.P. and C.R.; methodology, R.B.R., L.B.-F., K.B. and S.D.; software, S.D.; validation, R.B.R., L.B.-F., K.B., C.M., M.W., K.P., C.R. and A.M.; formal analysis, R.B.R., S.D. and C.M.; investigation, R.B.R., L.B.-F., K.B., C.M., M.W., K.P. and C.R.; resources, R.B.R., L.B.-F., K.B., C.M., M.W., K.P. and C.R.; data curation, R.B.R., S.D. and C.M.; writing—R.B.R., K.B. and S.D., Original draft preparation, R.B.R., L.B.-F., K.B. and S.D.; writing—review and editing, R.B.R., K.B., L.B.-F., M.W. and C.M.; visualization, S.D.; supervision, L.B.-F. and R.B.R.; project administration, S.D.; funding acquisition, L.B.-F. and K.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a Flinders University Establishment Grant.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research study received approval from Flinders University’s Human Research Ethics Committee, project identification id: 5845 on 13 January 2023; University of Canberra’s Human Research Ethics Committee, project id: 13514 on 05 September 2023; Australian Catholic University’s Human Research Ethics Committee, project id: 2023-3379R on 23 October 2023; and Charles Sturt University’s Human Research Ethics Committee, project id: H23807 on 10 December 2023. All deemed that the study adhered to the National Statement on Ethical Conduct requirements in Human Research.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because the data are part of an ongoing study. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author(s) declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- ACT Government. (2024). Permit to teach program extended [press release]. Available online: https://www.cmtedd.act.gov.au/open_government/inform/act_government_media_releases/yvette-berry-mla-media-releases/2024/permit-to-teach-program-expanded (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Australian Government. (2023a). National teacher workforce action plan. Available online: https://www.education.gov.au/national-teacher-workforce-action-plan (accessed on 8 December 2024).

- Australian Government. (2023b). Priority area 1, action 3: Expansion of nexus program to primary schools. Available online: https://www.education.gov.au/national-teacher-workforce-action-plan/announcements/priority-area-1-action-3-expansion-nexus-program-primary-schools (accessed on 8 December 2024).

- Australian Government Department of Education. (2023). Teacher workforce shortages: Issues paper. Australian Government. Available online: https://ministers.education.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/Teacher%20Workforce%20Shortages%20-%20Issues%20paper.pdf (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Beerkens, M., Mägi, E., & Lill, L. (2011). University studies as a side job: Causes and consequences of massive student employment in Estonia. Higher Education, 61, 679–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjorklund, P., Jr., Warstadt, M. F., & Daly, A. J. (2021). Finding satisfaction in belonging: Preservice teacher subjective well-being and its relationship to belonging, trust, and self-efficacy. Frontiers in Education, 6, 639435. [Google Scholar]

- Catholic Education South Australia. (n.d.). Special Authority for unregistered persons to Teach (TRT) policy. Available online: https://www.cesa.catholic.edu.au/working-with-us/working-in-catholic-education/preservice-teacher-scholarships-opportunities (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- Chalies, S., Xiong, Z., & Matthews, R. (2021). Mentoring and building professional competences of pre-service teachers: Theoretical proposals and empirical illustrations. Professional Development in Education, 47(5), 796–814. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2017). Thematic analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(3), 297–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darling-Hammond, L. (2015). The flat world and education: How America’s commitment to equity will determine our future. Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Darling-Hammond, L., Burns, D., Campbell, C., Goodwin, A. L., Hammerness, K., Low, E.-L., McIntyre, A., Sato, M., & Zeichner, K. (2017). Empowered educators: How high-performing systems shape teaching quality around the world. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Dekker, I., Chong, C. F., Schippers, M. C., van Schooten, E., & Delnoij, L. (2024). The right job pays: Effects of different types of work on study progress of pre-service teachers. Pedagogische Studiën, 101(1), 4–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Education. (2023). Strong beginnings: Report of the teacher education expert panel. Australian Government. Available online: https://www.education.gov.au/quality-initial-teacher-education-review/resources/strong-beginnings-report-teacher-education-expert-panel (accessed on 18 September 2024).

- Edwards, D., Britton, P., & Fettling, M. (2022). Sink or swim: A common induction program for pre-service teachers. In School-university partnerships—Innovation in initial teacher education (pp. 57–72). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, P. (2013). Mentoring as professional development:‘growth for both’mentor and mentee. Professional Development in Education, 39(5), 771–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, P. A. (2020). Teacher burnout turnaround: Strategies for empowered educators. WW Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Kearney, S. (2015). Reconceptualizing beginning teacher induction as organizational socialization: A situated learning model. Cogent Education, 2(1), 1028713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolb, D. A. (2014). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. FT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lave, J. (2009). The practice of learning. In Contemporary theories of learning (pp. 208–216). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Lave, J., & Chaiklin, S. (1993). Understanding practice: Perspectives on activity and context. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ledger, S., & Vidovich, L. (2018). Australian teacher education policy in action: The case of pre-service internships. Australian Journal of Teacher Education (Online), 43(7), 11–29. [Google Scholar]

- Longmuir, F. (2024). Australia’s teacher shortage: A generational crisis in the making. ABC News. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2023-01-30/pandemic-exposed-australia-teacher-shortage-students-schools/101886452 (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Murphy, S., Acquaro, D., Baxter, L., Miles-Keogh, R., Cuervo, H., & Walker-Gibbs, B. (2024). Developing quality community connections through a regional preservice teacher placement program. The Australian Educational Researcher, 52, 1087–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyt, B., Omey, E., Verhaest, D., & Baert, S. (2019). Does student work really affect educational outcomes? A review of the literature. Journal of Economic Surveys, 33(3), 896–921. [Google Scholar]

- NSW Education Standards Authority. (2019). Proficient teacher accreditation policy. Available online: https://educationstandards.nsw.edu.au/wps/wcm/connect/f5bfb718-2d02-41bd-8a7b-011160d7febe/proficient-teacher-accreditation-policy-2018.pdf?MOD=AJPERES (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Opoku, E., Sang, G., & Liao, W. (2020). Examining teacher preparation and on-the-job experience: The gap of theory and practice. International Journal of Research, 9(4), 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, J. R., Lynch, R., & Atit, K. (2023). Self-efficacy development in student teachers: The critical role of school placement. European Journal of Teacher Education, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronfeldt, M., Schwartz, N., & Jacob, B. A. (2014). Does preservice preparation matter? Examining an old question in new ways. Teachers College Record, 116(10), 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Singha, R., Singha, S., & Jasmine, E. (2024). The intersection of academics and career readiness. In Preparing students from the academic world to career paths: A comprehensive guide (pp. 246–266). IGI Global. [Google Scholar]

- Teach for Australia. (2023). Annual report: 2023. Available online: https://teachforaustralia.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/2023-Annual-Report.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Teacher Quality Institute (TQI). (2023). Teacher registration and permit to teach policy. Available online: https://www.tqi.act.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/2189140/09-20230228-Teacher-registration-and-PTT-policy-2023.pdf#:~:text=This%20policy%20sets%20out%20the%20framework%20for%20the,only%20suitably%20qualified%20teachers%20work%20in%20ACT%20schools (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Teachers Registration Board of South Australia. (2022). Special authority to teach (SAT). Available online: https://www.trb.sa.edu.au/Qualifications-to-Teach/professional-experience-pex/special-authority-to-teach-sat (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- Williams, L., & Sembiante, S. F. (2022). Experiential learning in US undergraduate teacher preparation programs: A review of the literature. Teaching and Teacher Education, 112, 103630. [Google Scholar]

- Zeichner, K. (2010). Rethinking the connections between campus courses and field experiences in college-and university-based teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 61(1–2), 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).