Women in Science: Where We Stand?—The WHEN Protocol

Abstract

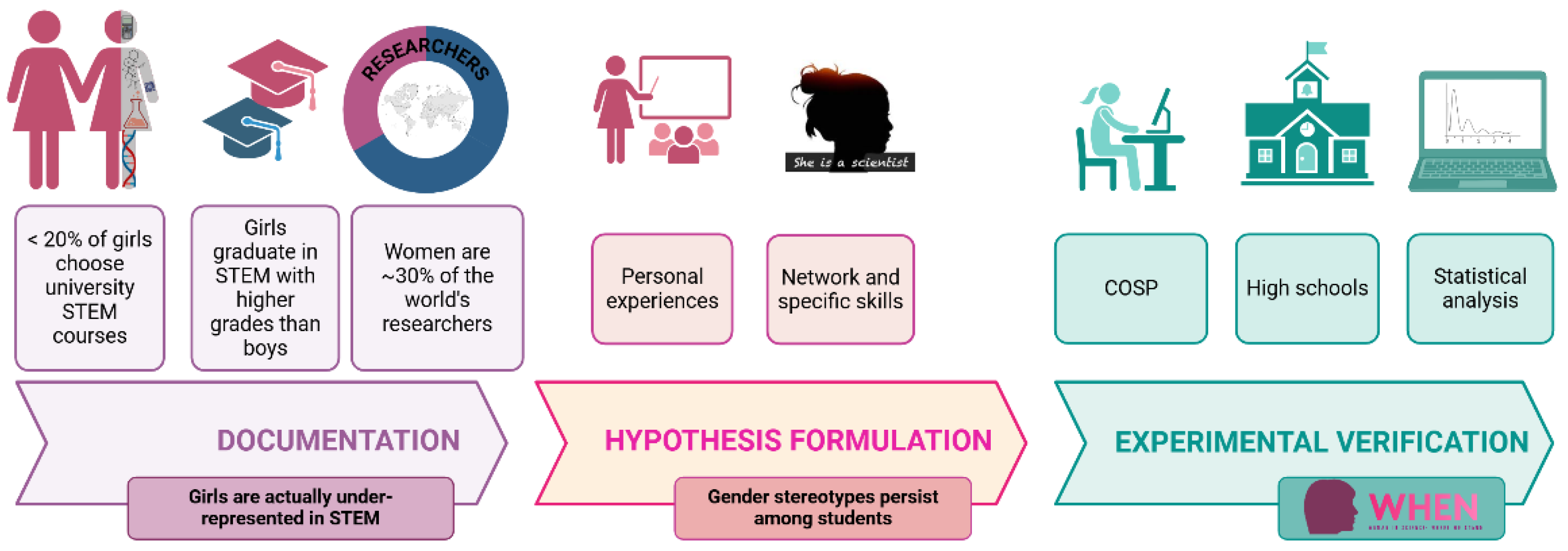

1. Introduction

2. Study Design

2.1. Objectives

- Do gender stereotypes in the scientific field still persist among pre-university high-school students despite societal changes and inclusion policies?

- What are the main challenges perceived by pre-university students, especially female students, regarding pursuing a scientific career?

- Is it possible to alter already-established stereotypes?

2.2. Study Phases

2.3. Population

2.4. Recruitment

- The study’s objectives;

- The execution methods;

- The assurance of anonymity;

- The voluntary nature of participation;

- The option for parents to review the questionnaires by contacting the study researcher via email up to the day before the scheduled orientation event;

- For parents of underage students, the possibility to opt out their kid from the study by notifying the researcher via email by the day before the scheduled orientation event.

3. Evaluations

3.1. Questionnaires

- The type of school the student attends;

- The student’s gender identity, including options beyond male/female, such as non-binary or a choice not to disclose;

- The occupational status of the student’s parents (Greene et al., 2013);

- The student’s current desired fields of study and career aspirations;

- Gender stereotypes associated with scientific subjects (adapted from the questionnaire by Mastera et al., 2021);

- Gender stereotypes linked to specific occupations (adapted from the Occupational Stereotype Measure by Hertz et al., 2018);

- Gender stereotypes related to the idea of scientists (adapted from the Adjective Checklist by Ashby & Wittmaier, 1978);

- Beliefs about the challenges that might be encountered when pursuing a scientific career.

- Satisfaction with the intervention;

- Interest in the topic;

- Changes in beliefs regarding the challenges of pursuing a scientific career.

- -

- No data from the questionnaires will be discussed or released to the participants.

- -

- Compliance with the questionnaire completion will be recorded.

- -

- The teachers who conducted the orientation event are invited to fill out an information sheet and a notice to collect some data (gender, age, SSD), and the type of activity carried out by the teacher with the students (seminar or laboratory activity), are recorded.

3.2. Analysis

3.3. Other Considerations

3.3.1. Study Costs

3.3.2. Withdrawal from the Study

3.3.3. Ethical Considerations

- -

- Informed Consent for Students

- The questionnaire is completely anonymous;

- The data will only be used for research purposes in an aggregated format;

- To proceed with completing the questionnaire, participants must accept the proposed conditions and sign the informed consent form;

- It is possible to interrupt the questionnaire at any time without any consequences.

- -

- Informed Consent for Teachers

3.3.4. Incentives

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Correction Statement

References

- Ashby, M. S., & Wittmaier, B. C. (1978). Attitude changes in children after exposure to stories about women in traditional or nontraditional occupations. Journal of Educational Psychology, 70, 945–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballarino, G., & Scherer, S. (2013). More investment, less returns? Changing returns to education in Italy across three decades. Stato e Mercato, 33(3), 359–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beutel, A. M., & Marini, M. M. (1995). Gender and values. American Sociological Review, 60(3), 436–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, F., & Nagelkerke, A. (2024). Editorial: Women in breast cancer, volume III: 2023. Frontiers in Oncology, 14, 1515282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilimoria, D., & Lord, L. (Eds.). (2014). Women in STEM careers: International perspectives on increasing workforce participation, advancement and leadership. Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bobbitt-Zeher, D. (2007). The gender income gap and the role of education. Sociology of Education, 80(1), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, P., & Passeron, J.-C. (1964). Les héritiers: Les étudiants et la culture (Repr). Éd. de Minuit. [Google Scholar]

- Ceci, S. J., & Williams, W. M. (2011). Understanding current causes of women’s underrepresentation in science. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 108(8), 3157–3162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheryan, S., Ziegler, S. A., Montoya, A. K., & Jiang, L. (2017). Why are some stem fields more gender balanced than others? Psychological Bulletin, 143(1), 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corbetta, P. (2014). Metodologia e tecniche della ricerca sociale (2nd ed.). Il mulino. [Google Scholar]

- De Vita, L., & Giancola, O. (2017). Between education and employment: Women’s trajectories in stem fields. Polis, 1, 45–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A. H., & Wood, W. (2011). Social role theory. In P. van Lange, A. Kruglanski, & E. T. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of theories in social psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 458–476). Sage Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Etzkowitz, H., Kemelgor, C., & Uzzi, B. (2000). Athena unbound: The advancement of women in science and technology. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. (2021). She figures 2021. Available online: https://europa.castillalamancha.es/sites/default/files/2021-11/ki0721083enn.en_.pdf (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- EUROSTAT. (2023). Science and technology workforce: Women in majority. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/w/ddn-20230602-1 (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- Giancola, O., & Piromalli, L. (2024). Capitale informativo, orientamento e percorsi scolastici. In O. Giancola, & L. Salmieri (Eds.), Disuguaglianze educative e scelte scolastiche (pp. 152–167). Franco Angeli. [Google Scholar]

- Giancola, O., & Salmieri, L. (2023). La povertà educativa in Italia. Dati, analisi, politiche. Carocci. [Google Scholar]

- Greene, F. J., Han, L., & Marlow, S. (2013). Like mother, like daughter? Analyzing maternal influences upon women’s entrepreneurial propensity. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 37, 687–711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hägglund, A. E., & Leuze, K. (2021). Gender differences in STEM expectations across countries: How perceived labor market structures shape adolescents’ preferences. Journal of Youth Studies, 24(5), 634–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heathcote, D., Savage, S., & Hosseinian-Far, A. (2020). Factors affecting university choice behaviour in the UK higher Education. Education Sciences, 10, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertz, S., Wood, E., Gilbert, J., Victor, R., Anderson, E., & Desmarais, S. (2018). Gender and compensation: Understanding the impact of gender and gender stereotypes in children’s rewards. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 5, 311–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, B. T., Srivastava, S., Leszko, M., & Condon, D. M. (2024). Occupational prestige: The status component of socioeconomic status. Collabra Psychology, 10(1), 92882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISTAT Istituto Nazionale di Statistica. (2023). Livelli di istruzione e ritorni occupazionali: Anno 2022. Available online: https://www.istat.it/it/files/2023/10/Report-livelli-di-istruzione-e-ritorni-occupazionali.pdf (accessed on 28 January 2025).

- Jaoul-Grammare, M. (2024). Gendered professions, prestigious professions: When stereotypes condition career choices. European Journal of Education, 59(2), e12603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M. K. (2001). Social origins, adolescent experiences, and work value trajectories during the transition to adulthood. Social Forces, 80(4), 1307–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumpal, I. (2013). Determinants of social desirability bias in sensitive surveys: A literature review. Quality & Quantity, 47(4), 2025–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leblebicioglu, G., Metin, D., Capkinoglu, B. A., & Cetin, P. S. (2011). The effect of informal and formal interaction between scientists and children at a science camp on their images of scientists. Science Education International, 3, 158–174. [Google Scholar]

- Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Hackett, G. (1994). Toward a unifying social cognitive theory of career and academic interest, choice, and performance. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 45(1), 79–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, P. (2006). ‘Someone like me can be successful’: Do college students need same-gender role models? Psychology of Women Quarterly, 30(1), 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastera, A., Meltzoffb, A., & Cheryanc, S. (2021). Gender stereotypes about interests start early and cause gender disparities in computer science and engineering. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 48, e2100030118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moss-Racusin, C. A., Dovidio, J. F., Brescoll, V. L., Graham, M. J., & Handelsman, J. (2012). Science faculty’s subtle gender biases favor male students. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 109(41), 16474–16479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Myers, K. R., Tham, W. Y., Yin, Y., Cohodes, N., Thursby, J. G., Thursby, M. C., Schiffer, P., Walsh, J. T., Lakhani, K. R., & Wang, D. (2020). Unequal effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on scientists. Nature Human Behaviour, 4, 880–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogilvie, M., & Harvey, J. (2000). The biographical dictionary of women in science: Pioneering lives from ancient times to the mid-20th century. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Olsson, M., & Martiny, S. (2018). Does exposure to counterstereotypical role models influence girls’ and women’s gender stereotypes and career choices? A review of social psychological research. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osservatorio Fondazione Deloitte. (2023). RiGeneration STEM: Le competenze del futuro passano da scienza e tecnologia. Deloitte. [Google Scholar]

- Santrock, J. W. (2013). Child development (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Schiebinger, L. (1989). The mind has no sex? Women in the origins of modern science. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman, J. (1980). Mathematics, spatial visualization, and related factors: Changes in girls and boys, grades 8–11. Journal of Educational Psychology, 72(4), 476–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steele, C. M. (1997). A threat in the air: How stereotypes shape intellectual identity and performance. American Psychologist, 52(6), 613–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephens, N. M., Markus, H. R., & Fryberg, S. A. (2012). Social class disparities in health and education: Reducing inequality by applying a sociocultural self model of behavior. Psychological Review, 119, 723–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viglione, G. (2020). Are women publishing less during the pandemic? Here’s what the data say. Nature, 581(7809), 365–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Question | Response Options |

|---|---|

| Type of School | Scientific High School, Humanistic High School, Technical Institute, Other |

| Grade Level | 4th Year, 5th Year |

| Geographic Area | Milan (City), Milan (Province), Other Province |

| Gender Identity | Woman, Man, Non-binary, Prefer not to answer |

| Mother’s Profession | Open-ended response |

| Father’s Profession | Open-ended response |

| Desired Future Profession | Open-ended response |

| Preferred University Field (max 2) | Mathematical and Computer Sciences, Physical Sciences, Chemical Sciences, Earth Sciences, Biological Sciences, Medical Sciences, Agricultural and Veterinary Sciences, Civil Engineering and Architecture, Industrial and Information Engineering, Humanities, Historical-Philosophical-Psychological Sciences, Legal Sciences, Economic and Statistical Sciences, Political and Social Sciences, Not Sure |

| How much do you think girls like STEM subjects? (1–6) | 1 (Not at all)–6 (A lot) |

| How much do you think boys like STEM subjects? (1–6) | 1 (Not at all)–6 (A lot) |

| How good do you think girls are at STEM subjects? (1–6) | 1 (Not at all)–6 (Very good) |

| How good do you think boys are at STEM subjects? (1–6) | 1 (Not at all)–6 (Very good) |

| How much do you personally like STEM subjects? (1–6) | 1 (Not at all)–6 (A lot) |

| Future Challenges in a Scientific Career (max 2) | Work-life balance, Study commitment, Financial sustainability, Job security, Gender-related obstacles, Career obstacles, Personal interests balance, Not suitable for this path, None, Other |

| Perceptions on Professions (indicate whether professions are best performed “mainly by women”, “mainly by men”, or “equally by both”) | Secretary, Kindergarten Teacher, Truck Driver, Nurse, Dancer, Firefighter, Scientist, Bricklayer, Librarian, Mechanic, Doctor |

| Attributes of a Female Scientist (max 3) | Competence, Cheerfulness, Coldness, Kindness, Precision, Intelligence, Tenacity, Reliability, Independence, Sensitivity, Many Interests, Organization |

| Attributes of a Male Scientist (max 3) | Competence, Cheerfulness, Coldness, Kindness, Precision, Intelligence, Tenacity, Reliability, Independence, Sensitivity, Many Interests, Organization |

| Question | Response Options |

| How much do you think girls like STEM subjects? (1–6) | 1 (Not at all)–6 (A lot) |

| How much do you think boys like STEM subjects? (1–6) | 1 (Not at all)–6 (A lot) |

| How good do you think girls are at STEM subjects? (1–6) | 1 (Not at all)–6 (Very good) |

| How good do you think boys are at STEM subjects? (1–6) | 1 (Not at all)–6 (Very good) |

| Perceptions on Professions (indicate whether professions are best performed “mainly by women”, “mainly by men”, or “equally by both”) | Secretary, Kindergarten Teacher, Truck Driver, Nurse, Dancer, Firefighter, Scientist, Bricklayer, Librarian, Mechanic, Doctor |

| Attributes of a Female Scientist (max 3) | Competence, Cheerfulness, Coldness, Kindness, Precision, Intelligence, Tenacity, Reliability, Independence, Sensitivity, Many Interests, Organization |

| Attributes of a Male Scientist (max 3) | Competence, Cheerfulness, Coldness, Kindness, Precision, Intelligence, Tenacity, Reliability, Independence, Sensitivity, Many Interests, Organization |

| Future Challenges in a Scientific Career (max 2) | Work-life balance, Study commitment, Financial sustainability, Job security, Gender-related obstacles, Career obstacles, Personal interests balance, Not suitable for this path, None, Other |

| Impact of Orientation Session | Information about university field, Study commitment required, Career prospects, Job opportunities, Expected salary, Work-life balance |

| Favourite Aspect of the Session | Open-ended response |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Arnaboldi, F.; Macagno, A.; Villani, M.; Biganzoli, G.; Bianchi, F. Women in Science: Where We Stand?—The WHEN Protocol. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 408. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040408

Arnaboldi F, Macagno A, Villani M, Biganzoli G, Bianchi F. Women in Science: Where We Stand?—The WHEN Protocol. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(4):408. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040408

Chicago/Turabian StyleArnaboldi, Francesca, Alessia Macagno, Marialuisa Villani, Giacomo Biganzoli, and Francesca Bianchi. 2025. "Women in Science: Where We Stand?—The WHEN Protocol" Education Sciences 15, no. 4: 408. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040408

APA StyleArnaboldi, F., Macagno, A., Villani, M., Biganzoli, G., & Bianchi, F. (2025). Women in Science: Where We Stand?—The WHEN Protocol. Education Sciences, 15(4), 408. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15040408