1. Introduction

Over recent decades, the intersection of creativity and education has attracted increasing scholarly attention (

Hernández-Torrano & Ibrayeva, 2020;

Shaheen, 2010). This growing academic focus reflects the global urgency for contemporary education systems to address critical challenges within the teaching profession (

Beghetto, 2017). In parallel,

UNESCO and International Task Force on Teachers for Education 2030 (

2024) has predicted a global shortage of at least 12 million educators by 2030, a shortfall that poses significant risks to the well-being and development of nations and their educational systems (

Hernández-Torrano & Ibrayeva, 2020;

Craft, 2002;

Cropley et al., 2019). Within this context, the nexus between creativity and education has garnered interest for two primary reasons: first, creativity is recognized as a critical skill that students must cultivate to thrive in the modern world (

Kanematsu & Barry, 2016); second, it is identified as a key professional attribute essential for effective teaching (

T. P. Patston et al., 2018;

Beghetto & Kaufman, 2016).

Although the relationship between creativity and education is not a novel subject, the specific exploration of creativity in teachers has advanced more slowly and lacks the depth observed in studies focusing on students, their academic outcomes, and classroom dynamics (

Bramwell et al., 2011;

Davies et al., 2014;

Paek & Sumners, 2019). Emphasizing creativity from a teacher-centered perspective is crucial, as research underscores the pivotal role teachers play in fostering students’ creative development (

T. P. Patston et al., 2018). Moreover, creative pedagogies are increasingly seen as essential for addressing pressing global challenges such as the ecological crisis, health emergencies, and the preservation of democratic values (

Canina et al., 2023;

Beghetto, 2017).

In this context, this study is relevant as it explores the different understandings of creativity, which may play a critical role in equipping future teachers to adequately face the aforementioned global challenges, and highlights the importance of enhancing teacher training programs to address the specific needs of preservice teachers (PSTs) (

Darling-Hammond, 2006;

Lawson et al., 2015), an underexplored area in teacher education literature. Researchers have noted that PSTs face distinct challenges compared to their more experienced counterparts (

Rivera Maulucci, 2013;

Deng et al., 2018). These include navigating reality shock (

Voss & Kunter, 2020), managing dual roles as students and educators (

Yuan et al., 2019), achieving professional recognition within the educational community (

Jokikokko & Uitto, 2017), and developing a coherent teaching philosophy to guide their practices in school settings (

Hong et al., 2018). Although research on creativity in teachers has highlighted factors like motivation, pre-existing mindsets, disciplinary content knowledge, and beliefs as significant (

Beghetto, 2017;

Vedenpää & Lonka, 2014;

Liu & Lin, 2013), it has yet to fully address the unique experiences of preservice teachers in ways that could inform the training and development of future educators (

Newton & Beverton, 2012).

While systematic literature reviews exist on various aspects of creativity, such as teachers’ perceptions of creativity (

Mullet et al., 2016), creativity in higher education teaching (

Han & Abdrahim, 2023), and creative learning environments (

Davies et al., 2014), no updated and comprehensive studies explicitly focus on preservice teachers (PSTs). Therefore, the following section presents a historical and comprehensive overview that critically examines the various transformations in the conceptualization of creativity and its relationship with the field of educational research. In this context, we conceptualize creativity as a phenomenon emerging from the convergence of collective, meaningful, and culturally mediated processes, oriented toward the transformation of reality and capable of generating original and contextually relevant outcomes (

Glăveanu, 2020). Consequently, we identify a gap in the existing literature concerning the limited understanding of the role creativity plays in the education of future teachers, their initial professional practice, and the formation of their professional beliefs. This gap is largely due to the absence of systematically consolidated evidence on the qualitative characteristics of PSTs as a workforce segment, as well as the predominant research themes, leading scholars, and countries contributing to this field of study. To bridge this gap, the present literature review examines scientific production from the past decade (2014–2024) to identify patterns, trends, and key insights regarding creativity and its role in PST education.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Approaches to the Concept of Creativity

The concept of creativity has evolved historically, undergoing continual reinterpretation through various perspectives and models, yet it remains a contested terrain.

Sawyer and Heriksen (

2024) describe a progression of three waves of research, each rooted in distinct disciplinary domains. According to these authors, the first wave is dominated by psychology, the second by cognitive sciences, and the third by an interdisciplinary convergence centered on creativity.

Brandt (

2021) argues that the conceptualization proposed by

Runco and Jaeger (

2012), which delineates creativity based on the criteria of originality and effectiveness, has been consolidated as a standard framework and extensively expanded within the field. Nevertheless, despite advancements in the discourse, some voices (e.g.,

Weisberg, 2015) advocate for alternative criteria such as value, task appropriateness, or adaptiveness. This perspective encourages a deeper examination of the concept’s definition, recognizing it as a task shaped by inherently subjective factors, and prompts critical reflection on the legitimacy and authority of those who arbitrate and influence the debate (

Brandt, 2021). In contrast, contributions such as

Rhodes’s (

1961) description of creativity as a qualitative rearrangement of specific or general knowledge for presentation to others remain central to contemporary conceptualizations and have inspired the development of new models.

In fact,

Rhodes’s (

1961) perspective has allowed the configuration of a 4Ps model (Person, Process Press, Product), which describes four interdependent strands of creativity that overlap and intertwine. Although they can be separated analytically, from this perspective, the four strands only operate functionally in unity. These different strands allude to the person who can be creative, the processes involved in generating an idea, the pressure from the environment that influences both the person and their processes, and the product as the materialization of an idea. Following this model, an idea is conceived by a person, developed through certain processes, and perceived as novel by the environment in which it is both conceived and introduced.

Another relevant problem in the understanding of creativity is associated with the Who and the label of genius that has historically been attached to the concept. In this respect,

Guilford (

1950) had already proposed a differentiation between the creativity of geniuses and everyday creativity.

Csikszentmihalyi (

1996), for his part, deepened this distinction by referring to a ‘creativity with a capital C’, as part of his flow theory, where maximum creativity is related to states of flow and personal fulfilment in highly complex activities.

Glăveanu (

2021) has synthesized these discussions by pointing out that creativity has been understood through paradigms that have emphasized either the role of the He who originates creativity, that of the I understood as a genius who possesses it, or that of a We associated with the collective that develops it.

To address the previously established duality between everyday creativity (Little-c) and ‘genius’ creativity (Big-C),

Kaufman and Beghetto (

2009) propose an approach in which creativity is categorized into four types: Mini-c, Little-c, Pro-C, and Big-C. These categories do not represent sequential stages but instead coexist on a continuum, offering greater flexibility in understanding the creative process.

The Mini-c category refers to creativity in its most personal and intimate form, characterized by novel and meaningful experiences for the individual, relatively independent of external evaluation. This type of creativity emerges within the learning process and through the personal interpretation of new experiences. In contrast, the Little-c category is associated with everyday creativity—creativity that is accessible to everyone in their daily lives. While this form of creativity does not necessarily reach a professional level, it is often evident in the immediate social context, particularly in solving common problems and creatively adapting to everyday situations.

Pro-C, by contrast, situates creativity within a professional or specialized domain, where the individual possesses a significant level of expertise and recognition in their field, and their creativity is valued within a specific community. However, this category does not yet achieve the ‘genius’ status associated with Big-C. The latter refers to creativity that has a profound and lasting impact on society. This type of creativity is often linked to great historical figures whose contributions transform their discipline and gain widespread recognition beyond their specific field.

2.2. Creativity in Education

The intersection of creativity and education plays a pivotal role in individual development, addressing both personal growth expectations and the need for adaptation to an increasingly dynamic world (

Hernández-Torrano & Ibrayeva, 2020;

Craft, 2002;

Marquis & Henderson, 2015;

Beghetto & Kaufman, 2016). Despite broad consensus on this point, the relationship between creativity and education has undergone a relatively recent redefinition, influenced by the economic perspectives of organizations such as the OECD. This redefinition has elevated creativity as a critical focus in shaping contemporary school curricula (

T. J. Patston et al., 2021). Consequently, this shift has progressively endorsed a theoretical reorientation that highlights creativity as an educational priority that transcends its traditional association with the arts (

Glăveanu, 2014;

Benedek et al., 2021;

T. P. Patston et al., 2018).

This composite focus on creativity and education can be understood through three central features: the thematic disaggregation of research, the identification of predominant areas of study, and the challenges teachers face in distinguishing between teaching with creativity and teaching for creativity (

T. J. Patston et al., 2021). Regarding the first point, some authors argue that the plurality of definitions and potential connections between creativity and education has resulted in an uneven development of this relationship, even prompting both supportive and critical perspectives on this association (

Feldman & Benjamin, 2006). Concerning the predominant areas of research,

Hernández-Torrano and Ibrayeva (

2020) identify four key themes: conceptualizations of creativity, teachers’ beliefs about creativity, methods for assessing creativity, and studies on creative learning environments. Finally, as noted by

T. J. Patston et al. (

2021), the growing consensus that creativity is teachable and that schools serve as a primary agent for fostering it has driven significant work on teacher-related practices. However, a clear distinction between creative teaching and teaching to develop creativity remains elusive, despite both approaches being essential and complementary.

2.3. Creativity, Teachers, and PSTs

The dispersion throughout the intersection of creativity and education is also reflected in research on teachers. In recent decades, studies on teachers and creativity have examined topics such as its links to playfulness (

Graham et al., 1989), implicit theories about creativity (

Chan & Chan, 1999), its relationship with teachers’ well-being (

Anderson et al., 2021), personality attributes that predict creativity (

Lee & Kemple, 2014), and educators’ beliefs about its nature (

Benedek et al., 2021;

T. P. Patston et al., 2018;

Bereczki & Kárpáti, 2018). However, these studies have not yet been integrated into a comprehensive analytical framework. Existing reviews primarily focus on teachers’ behaviors that promote creative thinking (

Brauer et al., 2024), creative teaching practices, and intervention experiences aimed at enhancing students’ performance. Meanwhile, the components and challenges of developing creativity in teachers themselves remain relatively underexplored.

This challenge takes on a specific connotation in the context of this review, which focuses on PSTs—those in the process of completing their professional practicum (

Lawson et al., 2015;

Cohen et al., 2013). This stage has been described as stressful and associated with profession-specific challenges (

Schmidt et al., 2017;

O’Connor, 2008), including the acquisition of professional status (

McCormack et al., 2006), the development of self-agency (

Steadman, 2021), the negotiation of dual professional identities (

Yuan et al., 2019), the ambiguity of simultaneously adopting the roles of teacher and student (

Yuan & Lee, 2015), the management of relationships with mentors (

Voss & Kunter, 2020), and the emotional demands inherent in this highly precarious position (

Ji et al., 2022). Consequently, understanding creativity in PSTs requires addressing these parallel processes, which are integral to a key phase in their professional development.

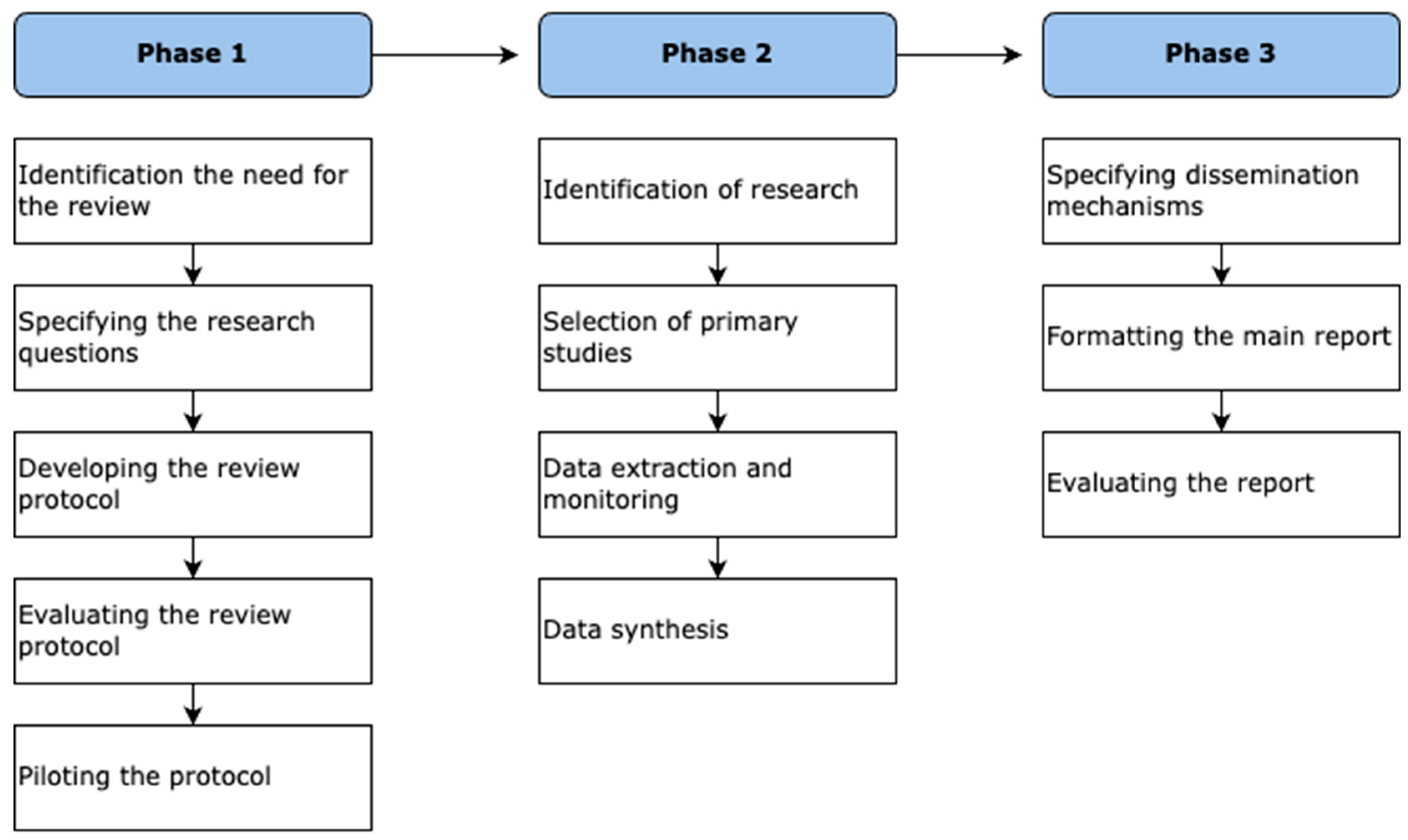

3. Materials and Methods

The search followed the guidelines of the PRISMA Statement (

Page et al., 2021). The process used to conduct the systematic literature review is illustrated in

Figure 1.

The methodology included activities ranging from the formal definition of research questions to the creation of inquiry strings for automated searches and the subsequent incorporation of manual peer review in the selection process. We selected the Web of Science (WOS) digital library for the search because it is one of the most established, reliable, and widely used sources of academic articles in the scientific community. The prestige of this database is based on the impact of the journals it indexes, the rigorous peer-review process, and the expert editors involved in the journals included in the database. Moreover, the WOS currently indexes articles across all fields of science and social sciences in a wide range of formats (including journal articles and conference proceedings), published independently by academic associations or by any of the major scientific publishers (including Elsevier, Springer, IEEE, ACM, Sage, etc.). Therefore, this database is particularly suitable for multidisciplinary searches. The specific search areas were the title, abstract, and keywords.

Accordingly, the Web of Science (WoS) Core Collection was selected as the primary database due to its rigorous inclusion criteria, which assess journals based on 28 quality and impact indicators. This selection ensures that the sources included in this study meet high scholarly standards, thereby enhancing the reliability and credibility of the review. Additionally, the research team had greater institutional access to the WoS compared to alternative databases, facilitating a more comprehensive and systematic data collection process. Furthermore, databases such as Scopus were deliberately excluded to prevent potential duplication of records and overlapping journal entries, thereby maintaining the integrity and precision of the dataset.

3.1. Research Questions

The overarching aim of this study is to systematically explore the literature that addresses the intersections between creativity and PSTs. Our goal is to identify patterns and dynamics within the field by organizing the bibliography around these underexplored themes. This effort seeks to support and encourage research that could benefit from an integrated approach to these topics of interest. Specifically, we focus on the following set of research questions:

Q1: What are the leading journals and countries publishing research on creativity and preservice teachers, and which keywords are employed? This question seeks to assess whether the academic production in this area is characterized by fragmentation or diversity.

Q2: How is the concept of creativity defined, and what are the primary topics explored in studies on creativity and preservice teachers? This question aims to uncover the key subtopics within teacher education and creativity research that are most frequently addressed at this intersection.

Q3: What are the primary conclusions, findings, and characteristics of the fieldwork conducted on creativity and preservice teachers? This question aims to synthesize existing knowledge, highlighting the methodological approaches, contexts, and trends in fieldwork while providing a comprehensive overview of the challenges, opportunities, and key outcomes identified in previous studies.

3.2. Search Strategy

3.2.1. Automatic Data Extraction

The search terms were based on two concepts: preservice teachers (teacher candidates, intern teachers, teacher trainees, teaching interns, aspiring teachers, or future teachers) and creativity (creative process, creative thinking, or imagination). As shown in

Table 1, the search targeted articles containing the word “creativity” and its synonyms found in the literature within the title, abstract, or keywords. Additionally, to be selected, an article also needed to include the term “teachers candidate” or any of its derivatives in the title, abstract, or keywords. We used seven variations for this concept, as our aim was to explore the relationship between creativity and teacher education.

To select the relevant studies for answering our research questions, we defined the following inclusion criteria:

Studies that intersect the topics of creativity and preservice teachers in the title, abstract, or keywords.

Works published in peer-reviewed scientific journals or conference proceedings.

Works written in English or Spanish.

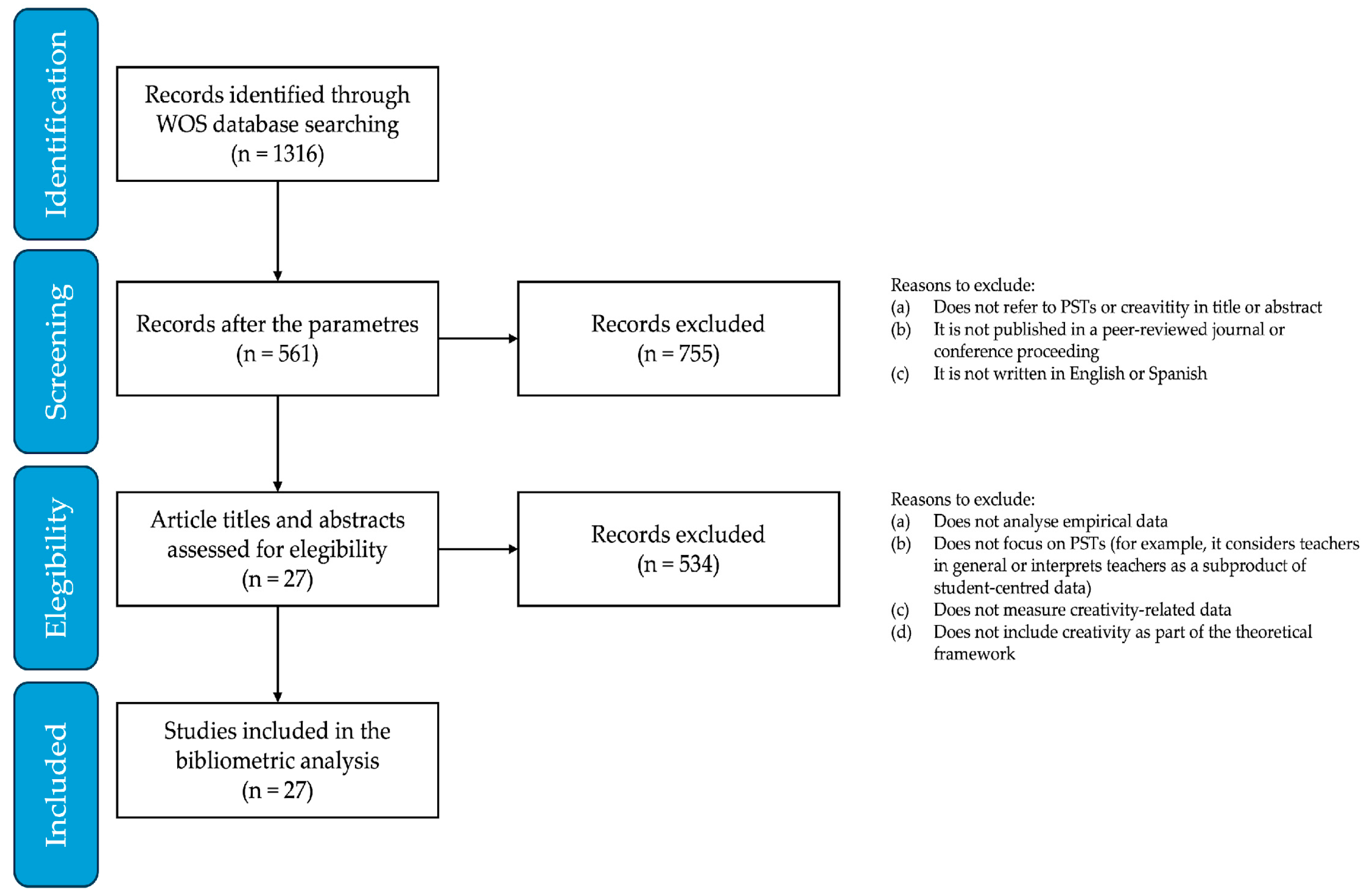

As shown in

Figure 2, these criteria were applied by setting filters in the digital library we used during Stage 1. Subsequently, articles were manually selected through abstract reading, corresponding to Stage 2. Finally, the criteria were iteratively considered during data extraction and article analysis in Stage 3.

3.2.2. Manual Exclusion of Data

Based on the 561 papers obtained from the search, the three authors collaboratively reviewed the abstracts, with each author reading 187 papers and marking them as “YES” if they effectively met the proposed inclusion criteria, “NO” if they did not, or “IDK” (I don’t know) if there was uncertainty about whether the paper fulfilled the eligibility criteria.

In a second phase, papers marked as “IDK” were reviewed by another author to determine whether they should be included. In this phase, the options were again “YES” if the paper met the inclusion criteria, “NO” if it did not meet the proposed parameters, or “IDK” if there was still uncertainty.

Papers marked as “IDK” in both reviews moved to a third stage, where the third author—who had not previously read the abstract—reviewed them and discussed the criteria with the group of authors to decide their inclusion. The manual exclusion process resulted in a total of 27 papers.

The 534 excluded papers were removed from the database because they did not meet the inclusion criterion related to preservice teachers. In general, these studies either mentioned “preservice teachers” but had samples consisting of in-service teachers or generalized findings to teachers, or they did not fulfill the criterion of being empirical studies.

3.2.3. Analysis Strategy

Once selected, we conducted a thematic content analysis (

Braun & Clarke, 2012) for each article. Following a deductive analysis logic, we directly examined the content of each article according to the following categories:

Region or country where the work was conducted. Subsequently, we categorized the region to which each country belongs as follows: North America, Europe, Oceania, Latin America and the Caribbean, Africa, East Asia, South Asia, Southeast Asia, the Middle East, Antarctica, or Multi Region (used when studies covered more than one region).

Central research question or general objective. The main questions or objectives around which the article revolves and seeks to answer.

Specific objectives or specific research questions. The questions and objectives through which the article aims to achieve its central objective.

Methods. Description of the research design strategy employed, as well as the research technique used.

Key findings. Description of the main findings and conclusions reported in the article.

Theory. The main theories around which the findings of the paper are discussed and the research is framed.

Definition of creativity. Identification of the concept of creativity used to support the theoretical framework from which the concept is discussed, as expressed in the theoretical section of this work.

4. Results

The authorship analysis reveals the existence of 76 authors in total. As can be seen in

Table 2, in terms of academic production, there are only three authors who have participated in the production of more than one paper at the crossroads of creativity and student teaching, these correspond to Katz-Buonincontro (three papers), Hass (two papers), and Perignat (two papers). As for the analysis of co-authorship, it is revealed that of the 76 authors that make up the sample of selected papers, only seven are connected to each other.

4.1. Bibliometric Results in Response to Q1: An Heterogeneous Field

4.1.1. Authors

The authorship analysis reveals the existence of 76 authors in total. As can be seen in the table, in terms of academic production, there are only three authors who have participated in the production of more than one paper at the crossroads of creativity and student teaching, these correspond to Katz-Buonincontro (three papers), Hass (two papers), and Perignat (two papers). As for the analysis of co-authorship, it is revealed that of the 76 authors that make up the sample of selected papers, only seven are connected to each other.

As for the most influential authors within the creativity and student teaching crossover, we find Katz-Buonincontro who has 17 citations and a total link strength of eight. In second place, we find Hass, who has 13 citations and a total link strength of four. Finally, there are Bae, Berezovska, and Budnyk with four citations and a total link strength of four. As for the most influential authors according to the number of citations, the leading authors in this ranking are Kemple and Lee with 45 citations and in second place are Lin and Wu with 30 citations.

4.1.2. Keywords and Internal Connections

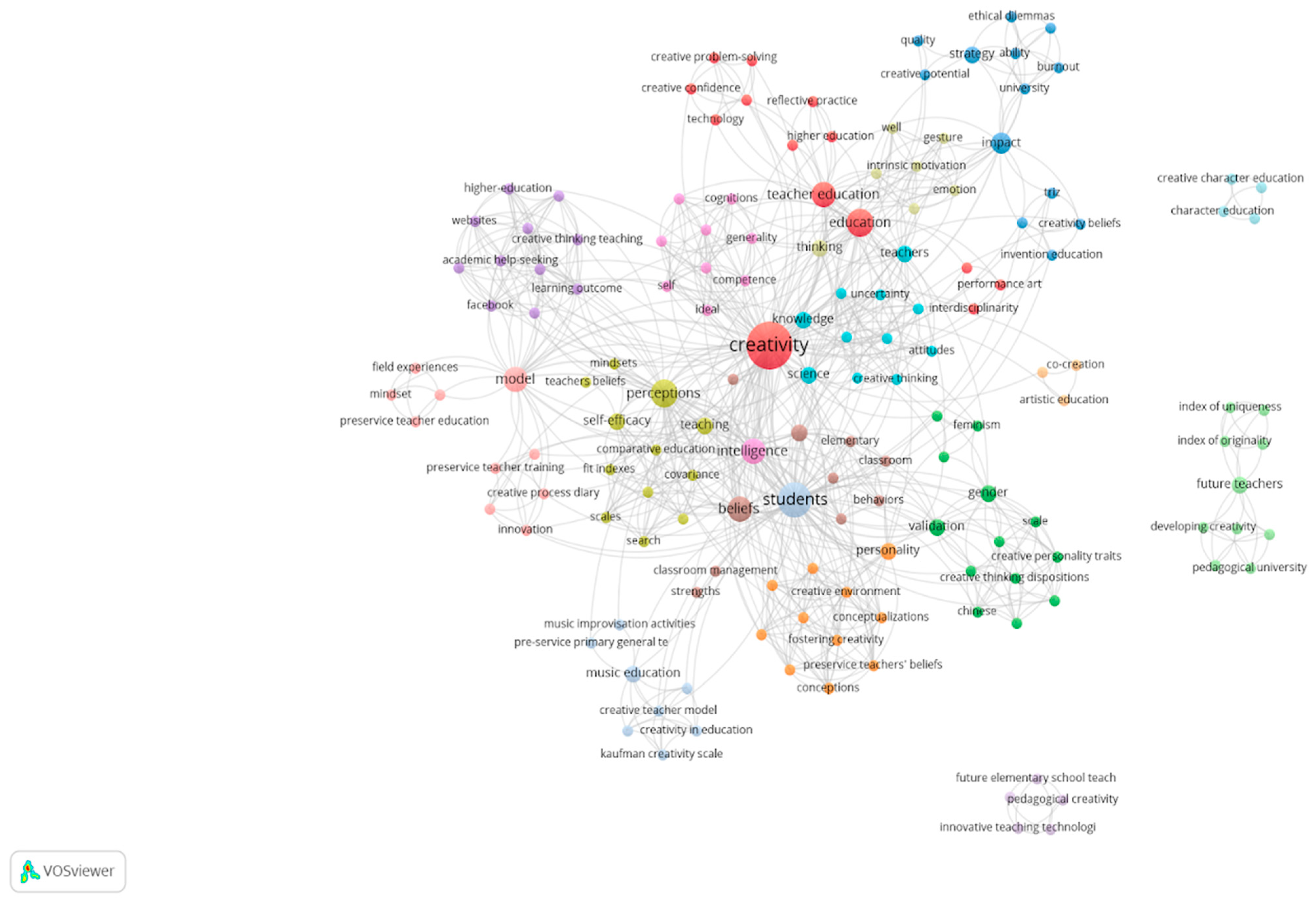

The co-occurrence analysis of all keywords reveals a total of 153 keywords, 134 of which are interconnected. Among the most prominent keywords, Creativity stands out with 14 occurrences and a total link strength of 110 points. In second place, Students appears eight times, with a total link strength of 74. In third place, Perceptions has a frequency of five occurrences and a total link strength of 52. Overall, the

Figure 3 comprises 16 clusters, with the main clusters centered around the following keywords.

The keyword network resembles a flower, with various petals radiating around the central pistil of Creativity, highlighting the concept’s centrality. The lower section, depicted in yellowish green, focuses on cognitive psychology, emphasizing psychometrics, covariance, scales, and related topics. Below that lies a more artistic and musical domain, rooted in education, with connections to performance and creative expression in artistic contexts. Toward the bottom right, in orange, is a more entrepreneurial cluster, centered on fostering creativity and its application in environmental, organizational, and entrepreneurial settings. Further to the right, in green, is an “identity” cluster, encompassing themes such as gender, feminism, Chinese studies, and personality traits. Above this, in blue, is a section examining the impact of creativity, representing a sociological exploration of creativity in teaching. Finally, at the top left, in red, lies a domain dedicated to creativity and teaching itself, featuring reflective and practical aspects, interdisciplinarity, and problem-solving as key components of learning models.

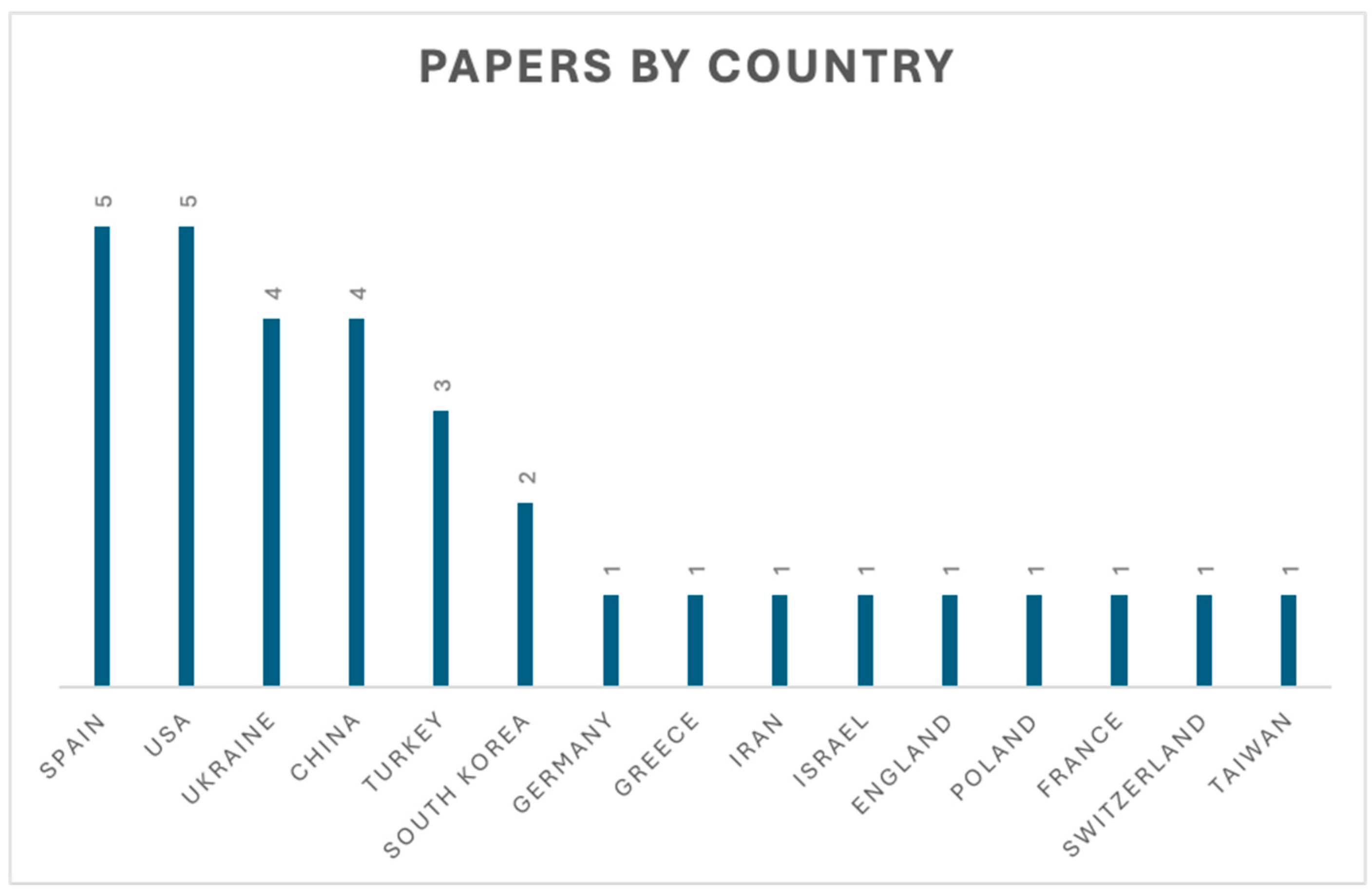

4.1.3. Results Considering Countries

An analysis of the geographical distribution of research output in this field reveals that the United States and Spain lead scholarly production, followed by Ukraine and China (see

Figure 4). While this distribution highlights key contributors to the discourse on creativity in teacher education, these findings must be interpreted with caution. The limited number of articles included in the final corpus constrains the generalizability of these results, and, more importantly, variations in national structures of teacher professionalization may influence how creativity is conceptualized and studied across different contexts. Pathways to professional teaching qualifications differ across countries, potentially shaping the methodological approaches and theoretical frameworks employed in creativity research. These discrepancies inevitably affect the extent to which this study can accurately capture the relationship between creativity and teacher education on a global scale.

Nevertheless, the predominance of the United States in this domain suggests the existence of an established academic tradition in the study of creativity, underpinned by the contributions of influential scholars such as Keith Sawyer, Mark Runco, and Mihály Csíkszentmihályi. Their extensive body of work, developed largely within American academic institutions, has significantly shaped contemporary understandings of creativity, influencing both theoretical perspectives and empirical investigations.

4.2. A Deductive-Inductive Strategy in Response to Q2

In order to approach the content of the articles included in this review, we have carried out a categorical analysis with a first inductive and a second deductive moment. While, from an inductive logic of analysis, we have concentrated on describing the definitions that each article provides of creativity and the main results of each one, from a deductive logic, we have categorized each research according to the strands, levels of contribution, and domains of creativity.

4.2.1. Deductive Phase

Strands of Creativity

First, we point out that some of the reviewed articles approach creativity by focusing on one or two of the four strands of creativity identified by

Rhodes (

1961): Creative Person, Creative Process, Press, or Product. Other studies adopt a more integrative perspective, combining multiple strands to address the complexity of the concept of creativity within their specific contexts. Notably, only a few articles (3) examine creativity through the lens of all four strands. A larger number focuses on two or three dimensions (16 and 5 articles, respectively), while another small subset (3) explores just one strand. Among the strands, Person and Process emerge as the most frequently studied, with 25 and 22 articles, respectively. In contrast, the Press dimension is addressed in only eight articles, and the Product strand appears in just seven.

Levels of Contribution

Similarly, we can describe the different levels of creative contribution on which each article concentrates. We note that most of the articles address creativity on the Little-c (25) and Pro-c (26) levels of contribution described by

Kaufman and Beghetto (

2009). Then, only a few of them focus on Mini-c (2), and none on Big-C. We can also note that only one of the articles studies creativity at three different levels of contribution, most of them (24) study it at the same time at two levels, and only two of them focus on only one level.

Domains of Creativity

It is also possible to differentiate the levels of specificity at which an idea or product can be considered creative, and different articles will focus on creativity in more or less specific ways. Being a literature review on creativity and teachers, it is to be expected that most of the articles (11) focus on a specific domain of creativity linked to teaching. Another 15 articles go a little further and describe industry specific aspects of creativity in teachers, concentrating on technology (2), music (2), early childhood (2), art (2), mathematics (1), drama (1), and language (1). Finally, only 3 of the articles deal with creativity in general.

Table 3 provides a summary of the results described above, highlighting intersections between the domains of creativity, levels of contribution, and strands of creativity. It is important to note that over 80% of the reviewed studies focus on the levels of Little-c and Pro-c, as well as the strands of Person and Process. Furthermore, approximately 40% of the articles concentrate on a specific domain of creativity within the teaching profession. Creativity at the individual contribution level is predominantly associated with general or specific domains of creativity, whereas studies addressing micro-domains specific to the profession, alongside those focusing on the strands of Press and Product, are more prevalent.

4.2.2. Inductive Reasoning

What Does Creativity Mean in the Literature?

The concept of creativity is still under constant definition. Therefore, our review shows that efforts to provide a consistent definition of the concept are not a generalizable feature of this corpus. After a review of the corpus, our analysis reveals that 14 of the 27 articles provide an explicit definition of what they mean by creativity in their work.

Table 4 below compiles these definitions.

As a result of this review, we detected multiple approaches to the concept. Among them, creativity has been described as an acquired behavior, a complex of individual qualities, the very act of generating new ideas, a meaningful human activity, a type of interaction between individual and society, a vector of solutions, an opposition to linearity, and, predominantly, an ability. Similarly, it is important to mention that the attributes of usefulness, novelty, and appropriateness that dominate the most consensual conceptualizations of creativity are also predominant in the definitions given.

A significant proportion of the reviewed studies approach creativity primarily as an individual phenomenon. With few exceptions, such as

Aparicio-Flores et al. (

2024) and

Lin and Wu (

2016), creativity is studied from the perspective of the individual, often without considering their relationship with society or the cultural tools available within their context. Consequently, the literature is predominantly characterized by studies designed from a methodologically individualist perspective (

Emirbayer, 1997), with limited engagement with research traditions such as those focusing on group creativity or sociocultural aspects of creativity (

Sawyer & DeZutter, 2009;

Glăveanu, 2020).

4.3. Results in Response to Q3: What Are the Foci of Study in Terms of Creativity and Preservice Teachers?

The reviewed articles reveal a variety of foci within the study of teacher creativity. Through the process of thematic content analysis, twenty-one (21) distinct concepts (or codes) were identified as the primary focus of each study. These concepts were subsequently grouped into four categories, which, while not mutually exclusive, serve as ideal types to simplify and organize the analysis. The resulting categories and their associated concepts are presented in

Table 5.

A comprehensive review of the literature highlights the centrality of prospective teachers’ beliefs about creativity as a critical area of focus in educational research (

Katz-Buonincontro et al., 2020a,

2020b). These beliefs are pivotal, as they form an essential component of teacher education and have the potential to influence both the development of self-efficacy and the pedagogical strategies employed in the classroom. Notably, while the reviewed studies reveal a consensus on the positive relationship between favorable beliefs about creativity and outcomes such as innovation (

Park, 2023), teaching effectiveness (

Cheung et al., 2019), and educators’ active engagement, evidence also indicates the existence of low creative self-perception among prospective teachers (

Echegoyen Sanz & Martín Ezpeleta, 2021). This latter phenomenon may impede the development of beliefs conducive to fostering creativity and innovation in educational settings.

In parallel, the literature underscores the significance of personal traits in understanding creativity among prospective educators. Key traits linked to fostering creativity include openness, empathy, self-reflection, and socio-emotional sensitivity (

Kimhi & Geronik, 2019;

Arikhan & Coban, 2021;

Cheung et al., 2019). These attributes can be particularly enhanced through targeted interventions, such as situational problem-solving scenarios and creative drama activities (

Briones et al., 2022). However, while these traits are recognized as conducive to creativity, the literature also identifies maladaptive perfectionism as a potential barrier (

Aparicio-Flores et al., 2024). Consequently, early identification of prospective teachers’ personal traits is crucial for providing tailored support during their professionalization process and mitigating risks that may hinder creativity.

Another significant dimension explored in the literature is related to creative processes. Evidence in this domain frequently intersects with research on personal traits, emphasizing that attributes such as empathy and socio-emotional sensitivity play a critical role in fostering creative processes essential for teacher education (

Durnali et al., 2023;

Chen et al., 2023;

Vuichard et al., 2023). Among the strategies highlighted are collaborative practices, problem-solving activities, co-creation initiatives, and performative methodologies (

Palacios et al., 2023). Collectively, these approaches not only promote creativity but also enhance inclusivity by engaging diverse educational stakeholders (

Torres Carceller, 2021).

A further area of investigation involves pedagogical approaches aimed at teaching for creativity. This strand overlaps with research on creative processes, particularly in its endorsement of interdisciplinary approaches and student-centered performance activities as critical for cultivating critical thinking and autonomy in the classroom (

Palacios et al., 2023). Additionally, the literature places strong emphasis on leveraging technology and digital platforms to expand opportunities for creative expression among students (

Lin & Wu, 2016). However, some studies are designed based on a conceptual overlap between creativity and innovation in this context, suggesting the need for greater definitional clarity in future research.

In summary, the evidence suggests that teaching practices oriented toward creativity not only enhance pedagogical effectiveness but also play a pivotal role in fostering transferable skills among students. These skills are integral not only to the cultivation of creativity but also to the broader development of competencies essential for successful integration into contemporary society (

Palacios et al., 2023).

5. Discussion

In response to Q1, our bibliometric analysis shows that research on creativity in preservice teachers (PSTs) is a highly fragmented and dispersed field, with a notable lack of cohesion in terms of research communities, authors, disciplinary areas, and conceptual approaches. As detailed in

Section 4.1, the authorship analysis reveals that only three authors have contributed more than one article in this intersection, suggesting the absence of a consolidated core of researchers in this area. Likewise, the co-authorship results show that collaboration among researchers is limited, with only seven authors connected to each other. The dispersion of the field is also reflected in the keyword analysis (

Section 4.1.2), where the semantic network of terms associated with creativity in PSTs is organized into multiple clusters without a clear central hierarchy. While “Creativity” is the most recurrent keyword, the variety of terms and connections suggests that studies approach creativity from multiple perspectives, often without a clear integration of approaches.

This pattern of fragmentation aligns with broader debates in creativity studies about whether it should be understood as a general construct or as a domain-specific phenomenon (

Baer, 2012,

2017;

Kaufman et al., 2017). The predominance of domain-centered approaches within the reviewed corpus suggests a disciplinary preference for understanding creativity in terms of specific contexts rather than as a transversal capacity. Nevertheless, the strong fragmentation of the literature lead us to consider consensus as fragile expressions of an expanding scientific field.

To answer Q2, our study adopted a mixed analysis strategy (deductive and inductive), allowing us to identify the main ways in which the literature conceptualizes creativity in PSTs. As presented in

Section 4.2, the deductive phase revealed that studies tend to classify creativity in terms of

Rhodes’s (

1961) four dimensions—Person, Process, Press, and Product—with a clear predominance of person- and process-centered approaches. This suggests that research in this field emphasizes individual characteristics and the cognitive mechanisms associated with creativity in future teachers, while contextual factors and tangible outcomes (product) receive less attention.

Moreover, the review identified that most studies position creativity within the Little-c and Pro-c levels, according to

Kaufman and Beghetto’s (

2009) typology, suggesting a predominant focus on everyday and professional forms of creativity in teaching. In contrast, very few studies were found to explore creativity at the Mini-c (emergent personal creativity) or Big-C (eminently recognized creativity) levels, indicating a lack of research on creativity in initial teacher training from a transformative or highly innovative perspective.

From an inductive perspective, the analysis of definitions (

Section 4.2.2) showed notable diversity in how studies conceptualize creativity, with definitions describing it as a skill, an acquired behavior, a set of individual qualities, an idea-generation process, a human activity, a social interaction, or even a vector of solutions. However, a clear trend in the corpus is the predominance of definitions framing creativity as a “skill” (

Chen et al., 2023;

Kimhi & Geronik, 2019), reinforcing the idea that studies on creativity in PSTs often focus on individual capacities rather than sociocultural factors.

This methodological preference for individualistic approaches results in limitations in understanding creativity as a relational and situated phenomenon. As argued in recent studies on sociocultural creativity (

Glăveanu, 2020), it is necessary to expand the focus toward models that recognize creativity in teacher training as a collective and culturally mediated practice. Additionally, the methodological approaches employed to study creativity in PSTs reveal tensions that warrant further exploration. Given the fragmented nature of the field, creativity is variably treated as either a supplementary unit of analysis—such as a contrast variable or contextual dimension in qualitative studies—or as the primary focus of inquiry. The broad range of definitions and the frequent reliance on implicit or poorly articulated conceptual frameworks exacerbate this ambiguity. This variability makes it challenging to identify studies that specifically address PSTs as a distinct population. Although this issue aligns with longstanding debates over the definition of creativity, it highlights a persistent problem: even widely accepted definitions struggle to gain consistent application in empirical research.

Results discussed in response to Q3 also suggest that creativity in PSTs is frequently assessed through the lens of knowledge transmission, which remains a central aspect of educational practice. While knowledge transmission is undeniably vital for future educators, this focus risks oversimplifying the multifaceted nature of creativity in teaching. The dominant interpretation of “teaching for creativity” reveals a critical tension: creativity is primarily framed as a goal for teachers to achieve in their classrooms, with insufficient attention to the processes through which teachers can cultivate creativity in themselves for both personal growth and pedagogical purposes. Constructivist and sociocultural approaches that challenge the notion of creativity as an innate talent could offer valuable insights, identifying opportunities and mechanisms for teachers to develop as creative agents (

Glăveanu, 2020). Such perspectives would prevent creativity from being reduced to a mere byproduct of teacher-student interactions, instead positioning it as an integral component of teacher identity and professional practice. In other words, while these studies highlight the role of PSTs in shaping student experiences, they often fail to foreground educators as independent agents, overlooking broader discussions about professional development and teacher subjectivity.

A recurring trend in the analyzed studies is their predominantly individual-centered approach. For instance, research on beliefs about creativity—one of the most prominent themes in the sample—tends to examine how such beliefs influence educators’ decisions or evaluations of creativity in the classroom. However, this body of work often neglects the contextual and social dimensions crucial to understanding creativity as a relational, culturally embedded phenomenon (cf.

Glăveanu, 2020). From this perspective, future research should address the limitations of methodological individualism (e.g.,

Emirbayer, 1997;

Archer, 2010), which underemphasizes the relational aspects of creativity, particularly in educational contexts.

Finally, the reviewed studies highlight a significant intersection between research on creativity in PSTs and the use of technology to enhance student learning outcomes. This trend frequently aligns creativity research with innovation, often equating the latter with the use of digital tools and media. While this approach emphasizes interactive and collaborative elements (e.g., discussion forums, blogs, and technology-based projects), it also risks conflating creativity with innovation. This conceptual conflation reflects broader challenges in the field, including the use of overly broad or informal definitions of creativity and, in some cases, a lack of grounding in scientifically rigorous conceptual frameworks, as evidenced in

Table 4.

6. Conclusions

This review highlights a notable conceptual instability in the use of the term “creativity.” Nearly half of the reviewed studies lacked explicit definitions of creativity or failed to ground their analyses in the most current and systematic research on the topic. This gap suggests that, while creativity has long been a subject of interest, its conceptualization within the lives and professional practices of teachers remains fragmented. Such fragmentation undermines the comparability and coherence of research designs and findings. While this lack of conceptual clarity poses a limitation and a potential threat to the reliability of some studies, it also reflects a broader theoretical debate. The domain-specific nature of creativity remains a contested issue, underscoring that the professional creativity of teachers, particularly PSTs, is still an open question requiring further exploration and theoretical refinement.

Therefore, this study contributes to consolidating knowledge on the relationship between creativity and PSTs by analytically deconstructing the central themes reported in the existing literature. These themes encompass beliefs about creativity, personal attributes associated with creativity, teaching for creativity, and the understanding of comprehensive creative processes. Furthermore, the study includes an examination of the conceptual frameworks employed by the authors reviewed, enabling a characterization of the field as predominantly fragmented, shaped by a diverse array of agents and institutions.

A detailed review of these studies reveals significant methodological, theoretical, and empirical concerns within the field. From a methodological perspective, there is a pressing need to expand beyond the methodological individualism that dominates much of the existing research. The complexity of creativity as a phenomenon necessitates the development of research strategies that contextualize the subject, situating individuals within their broader social and environmental settings. Systemic, relational approaches that account for the theoretical and practical dimensions of the studied population are essential for a nuanced understanding of the interplay between personal beliefs about creativity and the collective contexts in which creativity is explicitly or systematically cultivated.

These considerations also raise critical questions about how creativity is currently incorporated into teacher training curricula. On one hand, the literature includes studies that treat creativity as a given, relying on common-sense notions that risk undermining efforts to professionalize creativity as an integral aspect of teaching practice. On the other hand, the fragmented and underdeveloped state of the field may reflect broader challenges faced by the teaching profession globally, as outlined earlier in this discussion. This precarious situation underscores the need for further exploration of the distinctive elements of teachers’ creativity compared to other disciplines.

Finally, in a world characterized by rapid change, environmental crises, and political instability, this study invites renewed reflection on the role of teachers in fostering creative capacities that address pressing societal challenges. The evolving demands on education professionals necessitate a deeper engagement with creativity as a critical skill for navigating and responding to these global issues. By advancing our understanding of creativity in PSTs, this study seeks to inform educational frameworks that prepare future teachers to contribute meaningfully to the development of creative solutions for a complex and uncertain world.

7. Limitations and Future Research

This analysis reveals limited integration of established educational literature addressing the specific characteristics of PSTs and their formative stage. Dimensions such as the construction of professional identity, the hybrid nature of their roles, and the unique challenges they face during this phase are often overlooked. This oversight risks conflating research on PSTs with that on teachers in other developmental stages, omitting critical factors that may influence the role of creativity in their work. Addressing this gap requires positioning PSTs as the central focus of inquiry, rather than as secondary or derivative subjects studied through the lens of student outcomes or experiences. A stronger integration of sociocultural theories could help address these limitations, offering a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between creativity and PSTs within their specific formative contexts.

The diversity and limited scope of the research corpus allow only for a preliminary outline of the specific field concerning the relationship between PSTs and creativity. Accordingly, the conclusions of this study are constrained by the breadth of the corpus and the reliance on a single database (WoS Core Collection). The thematic diversity, the varying conceptualization of creativity across studies, and the differing populations examined impose limitations on comparative analyses of samples and results, as well as on the derivation of more robust conclusions in the medium term.

Nevertheless, several directions for future research can be identified. First, it is essential that forthcoming studies establish creativity as a scientific concept grounded in a well-defined body of scholarship, thereby distinguishing it from its common-sense interpretations. Advancing this distinction requires not only deepening the scientific understanding of creativity but also prioritizing the dissemination of emerging research in the field. Second, despite the constraints of the sample, our analysis identified a thematic repertoire comprising beliefs, personal traits, teaching for creativity, and creative processes. This repertoire could serve as the basis for a systematic research agenda, fostering a more comprehensive understanding of creativity by integrating differentiated temporalities and modes of agency.

Furthermore, this study has sought to address a knowledge gap specific to PSTs, leading to implications for the training of future teachers. A fundamental consideration is that creativity is a teachable skill, and prospective teachers are positioned at a critical juncture in its development. On the one hand, they must cultivate creativity in their students; on the other, they must develop it within themselves to become effective facilitators of creative learning. Second, research on creative processes suggests that unconventional pedagogical strategies—such as performance, theatre, and playful activities—serve as pivotal mechanisms for the professional growth of future teachers. Accordingly, we advocate for the greater integration of these approaches within teacher education curricula to counteract rigidity and individual dispositions (such as inflexibility) that may inhibit the development of creativity.

Finally, our conceptual approach to creativity, along with the critical discussion presented, underscores the risks of individualism in academic research on the phenomenon, while also identifying it as a potential obstacle in teacher education. In this regard, our study highlights the importance of exposing future educators to interdisciplinary dialogue, enabling them to engage with diverse perspectives and to enhance the inherently collective nature of creative and collaborative processes. In line with this, future research should examine how teachers with higher levels of creativity may also experience greater job satisfaction and stronger commitment to the profession, potentially mitigating issues such as teacher attrition and workforce instability.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.M.-S.; methodology, I.J., and D.C.-Z.; software, I.J.; validation, Y.M.-S., I.J., and D.C.-Z.; formal analysis, I.J., and D.C.-Z.; investigation, Y.M.-S., I.J., and D.C.-Z.; data curation, I.J. and D.C.-Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.M.-S., I.J., and D.C.-Z.; writing—review and editing, Y.M.-S., I.J., and D.C.-Z.; supervision, Y.M.-S.; project administration, Y.M.-S.; funding acquisition, Y.M.-S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Agency of Research and Development of Chile (ANID)/FONDECYT INICIACIÓN—Nº 11240401.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created during the elaboration of this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

Appendix A

| Cluster | Keyword | Occurrences | Total Link Strength |

| 1 | Case study | 1 | 14 |

| Cognitions | 1 | 11 |

| Competence | 1 | 11 |

| Creativity development | 1 | 14 |

| Design | 1 | 14 |

| Education | 7 | 59 |

| Framework | 1 | 14 |

| Game | 1 | 14 |

| Generality | 2 | 25 |

| Ideal | 1 | 11 |

| Implementation | 1 | 11 |

| Learning environments | 1 | 14 |

| pedagogical beliefs | 1 | 14 |

| Perfectionistic automatic thoughts | 1 | 11 |

| Performance | 1 | 14 |

| Primary education teachers | 1 | 11 |

| Qualitative evidence | 1 | 14 |

| Self | 1 | 11 |

| Specificity | 2 | 25 |

| Technology use | 1 | 14 |

| 2 | Achievement | 1 | 10 |

| Conceptions | 1 | 14 |

| Conceptualizations | 1 | 14 |

| Creative environment | 1 | 14 |

| Creative individuals | 1 | 14 |

| Early childhood education | 1 | 14 |

| Fostering creativity | 1 | 14 |

| Identities | 1 | 10 |

| Implicit theories | 1 | 14 |

| Personality | 3 | 30 |

| Preservice teachers’ beliefs | 1 | 14 |

| Qualitative | 1 | 10 |

| Researchers | 1 | 14 |

| Students | 10 | 98 |

| Views | 2 | 24 |

| 3 | Chinese | 1 | 10 |

| Creative learning environments | 1 | 10 |

| Creative personality traits | 1 | 10 |

| Creative thinking dispositions | 1 | 10 |

| Environmental education | 1 | 6 |

| Feminism | 1 | 6 |

| Gender | 2 | 16 |

| Interdisciplinary approach | 1 | 6 |

| Scale | 1 | 10 |

| School | 1 | 10 |

| Skills | 1 | 10 |

| Teachers’ creativity fostering behaviors | 1 | 10 |

| Validation | 2 | 19 |

| 4 | Comparative education | 1 | 12 |

| Covariance | 1 | 12 |

| Fit indexes | 1 | 12 |

| Intelligence | 4 | 46 |

| Measurement | 1 | 12 |

| Mindsets | 1 | 3 |

| Perceptions | 6 | 62 |

| Scales | 1 | 12 |

| Search | 1 | 12 |

| Self-efficacy | 2 | 15 |

| Student creativity | 1 | 12 |

| Teachers beliefs | 1 | 3 |

| Teaching | 2 | 22 |

| 5 | Ability | 1 | 6 |

| Burnout | 1 | 6 |

| Creative potential | 1 | 3 |

| Creativity beliefs | 1 | 6 |

| Ethical dilemmas | 1 | 6 |

| Impact | 3 | 22 |

| Invention education | 1 | 6 |

| Quality | 1 | 3 |

| Strategy | 2 | 9 |

| Stress | 1 | 6 |

| Teaching self-efficacy | 1 | 6 |

| TRIZ | 1 | 6 |

| University | 1 | 6 |

| 6 | Artistic creativity | 1 | 6 |

| Creative teacher model | 1 | 6 |

| Creativity in education | 1 | 6 |

| Initial training | 1 | 5 |

| Kaufman creativity scale | 1 | 6 |

| Music | 2 | 15 |

| Music education | 3 | 14 |

| Music improvisation activities | 1 | 3 |

| New teachers | 1 | 5 |

| Preservice primary general teacher-students | 1 | 3 |

| Relationship | 1 | 6 |

| Teacher–student relationship | 1 | 5 |

| 7 | Academic help-seeking | 1 | 13 |

| Creative thinking teaching | 1 | 13 |

| Facebook | 1 | 13 |

| Higher education | 1 | 13 |

| Learning outcome | 1 | 13 |

| Motivation | 1 | 13 |

| Perceived playfulness | 1 | 13 |

| Systems | 1 | 13 |

| University students | 1 | 13 |

| Web-based instruction | 1 | 13 |

| Websites | 1 | 13 |

| 8 | Attitudes | 1 | 12 |

| Creative thinking | 1 | 12 |

| Emotional intelligence | 1 | 12 |

| Entrepreneurship | 1 | 12 |

| Knowledge | 3 | 36 |

| Science | 2 | 22 |

| Structural equation modeling (SEM) | 1 | 12 |

| Teacher candidate | 1 | 12 |

| Teachers | 2 | 22 |

| Uncertainty | 1 | 12 |

| Validity | 1 | 12 |

| 9 | Behaviors | 1 | 9 |

| Beliefs | 4 | 33 |

| Big-5 | 1 | 9 |

| Classroom | 1 | 9 |

| Classroom management | 1 | 2 |

| Cognition | 2 | 19 |

| Elementary | 1 | 9 |

| Openness | 1 | 9 |

| Strengths | 1 | 2 |

| Teachers’ conceptions | 1 | 10 |

| 10 | Creative confidence | 1 | 6 |

| Creative problem-solving | 1 | 6 |

| Creativity | 17 | 131 |

| Design thinking | 1 | 6 |

| Empathy | 1 | 6 |

| Higher education | 1 | 5 |

| Reflective practice | 1 | 5 |

| Teacher education | 4 | 27 |

| Technology | 1 | 6 |

| Visual art | 1 | 5 |

| 11 | Developing creativity | 1 | 5 |

| Future teachers | 2 | 9 |

| Higher education students | 1 | 5 |

| Index of originality | 1 | 4 |

| Index of uniqueness | 1 | 4 |

| Non-verbal creativity | 1 | 4 |

| Pedagogical activity | 1 | 4 |

| Pedagogical conditions | 1 | 5 |

| Pedagogical university | 1 | 5 |

| Ranking | 1 | 5 |

| 12 | Creative process diary | 1 | 7 |

| Field experiences | 1 | 4 |

| Innovation | 1 | 7 |

| Mindset | 1 | 4 |

| Model | 5 | 44 |

| Multivariate factors | 1 | 7 |

| Preservice teacher education | 1 | 4 |

| Preservice teacher training | 1 | 7 |

| Psychology | 1 | 7 |

| Qualitative research | 1 | 4 |

| 13 | Emotion | 1 | 10 |

| Gesture | 1 | 10 |

| Intrinsic motivation | 1 | 10 |

| Storytelling | 1 | 10 |

| Thinking | 2 | 20 |

| Torrance tests | 1 | 10 |

| Well | 1 | 10 |

| 14 | Collaboration | 1 | 6 |

| Creative pedagogy | 1 | 6 |

| Diffractive analysis | 1 | 6 |

| Embodied dialogic space | 1 | 6 |

| Inquiry | 1 | 6 |

| Science and arts | 1 | 6 |

| 15 | Collaborative learning | 1 | 5 |

| Creative education | 1 | 5 |

| Creative pedagogies | 1 | 5 |

| Multiple case study | 1 | 5 |

| Student | 1 | 5 |

| Wiki-based learning | 1 | 5 |

| 16 | Future elementary school teachers | 1 | 4 |

| Innovative teaching technologies | 1 | 4 |

| Pedagogical creativity | 1 | 4 |

| Training of future teachers | 1 | 4 |

| Vocational education | 1 | 4 |

| 17 | Character education | 1 | 3 |

| Creative character education | 1 | 3 |

| Creativity education | 1 | 3 |

| Mathematics teacher education | 1 | 3 |

| 18 | Artistic education | 1 | 3 |

| Co-creation | 1 | 3 |

| Creative processes | 1 | 3 |

| 19 | Interdisciplinarity | 1 | 4 |

| Performance art | 1 | 4 |

| Project-based learning | 1 | 4 |

References

- Anderson, R. C., Bousselot, T., Katz-Buoincontro, J., & Todd, J. (2021). Generating buoyancy in a sea of uncertainty: Teachers creativity and well-being during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 614774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio-Flores, M., Fernández-Sogorb, A., Faubel, R. P. E., & Gonzálvez, C. (2024). Creativiy and perfectionistic automatic thoughts in teachers in training. Aula Abierta, 53(1), 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, M. (2010). Critical realism and relational sociology: Complementarity and synergy. Journal of Critical Realism, 9(2), 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arikhan, E., & Coban, S. (2021). The relationship between the creativity levels of music pre-service teachers and the preferences of a teacher model supporting creativity. Revista de Cercetare Si Interventie Sociala, 72, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyildiz, P., & Yilmaz, A. (2021). ‘Moving the kaleidoscope’ to see the effect of creative personality traits on creative thinking dispositions of preservice teachers: The mediating effect of creative learning environments and teachers’ creativity fostering behavior. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 41, 100879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, J. (2012). Domain specificity and the limits of creativity theory. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 46, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baer, J. (2017). Content matters: Why nurturing creativity is so different in different domains. In R. Beghetto, & B. Sriraman (Eds.), Creative contradictions in education (Vol. 1). Creativity theory and action in education. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balkin, A. (1990). What is creativity? What is it not? Music Educators Journal, 76(9), 29–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beghetto, R. A. (2017). Creativity in teaching. In J. C. Kaufman, V. P. Glăveanu, & J. Baer (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of creativity across domains (pp. 549–564). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beghetto, R. A., & Kaufman, J. C. (2007). Toward a broader conception of creativity: A case for mini-c creativity. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 1, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beghetto, R. A., & Kaufman, J. C. (Eds.). (2016). Nurturing creativity in the classroom (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Benedek, M., Karstendiek, M., Ceh, S. M., Grabner, R. H., Krammer, G., Lebuda, I., Silvia, P. J., Cotter, K. N., Li, Y., Hu, W., Martskvishvili, K., & Kaufman, J. C. (2021). Creativity myths: Prevalence and correlates of misconceptions on creativity. Personality and Individual Differences, 182, 111068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bereczki, E. O., & Kárpáti, A. (2018). Teachers’ beliefs about creativity and its nurture: A systematic review of the recent research literature. In Educational research review (Vol. 23, pp. 25–56). Elsevier Ltd. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bramwell, G., Reilly, R. C., Lilly, F. R., Kronish, N., & Chennabathni, R. (2011). Creative teachers. Roeper Review, 33(4), 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandt, A. (2021). Defining creativity: A view from the Arts. Creativity Research Journal, 33(2), 81–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brauer, R., Ormiston, J., & Beausaert, S. (2024). Creativity-fostering teacher behaviors in higher education: A transdisciplinary systematic literature review. In Review of educational research. SAGE Publications Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2012). Thematic analysis. In H. Cooper, P. M. Camic, D. L. Long, A. T. Panter, D. Rindskopf, & K. J. Sher (Eds.), APA handbook of research methods in psychology, Vol. 2. Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological (pp. 57–71). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Briones, E., Gallego, T., & Palomera, R. (2022). Creative drama and forum theatre in initial teacher education: Fostering students’ empathy and awareness of professional conflicts. Teaching and Teacher Education, 117, 103809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budnyk, O., Mazur, P., Matsuk, L., Berezovska, L., & Vovk, O. (2021). Development of professional creativity of future teachers (Based on comparative research in Ukraine and Poland). Revista Amazonia Investiga, 10(44), 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canina, M., Bruno, C., & Glaveanu, V. (2023). Innovating in the post-Anthropocene era: A new framework for creativity. In D. D. Preiss, M. Singer, & J. C. Kaufman (Eds.), Creativity, innovation, and change across cultures. Palgrave studies in creativity and culture. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, D. W., & Chan, L. K. (1999). Implicit theories of creativity: Teachers’ perception of student characteristics in Hong Kong. Creativity Research Journal, 12(3), 185–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K., Chen, J., & Wang, C. (2023). The effects of two empathy strategies in design thinking on pre-service teachers’ creativity. Knowledge Management and E-Learning, 15(3), 468–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, S. K., Fong, R. W.-t., Leung, S. K. Y., & Ling, E. K.-w. (2019). The roles of Hong Kong preservice early childhood teachers’ creativity and zest in their self-efficacy in creating child-centered learning environments. Early Education and Development, 30(6), 788–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E., Hoz, R., & Kaplan, H. (2013). The practicum in preservice teacher education: A review of empirical studies. In Teaching education (Vol. 24, pp. 345–380). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craft, A. (2002). Continuing professional development: A practical guide for teachers and schools. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cropley, D. H., Patston, T., Marrone, R. L., & Kaufman, J. C. (2019). Essential, unexceptional and universal: Teacher implicit beliefs of creativity. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 34, 100604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Creativity. In Flow and the psychology of discovery and invention (1st ed.). Harper Collins. [Google Scholar]

- Darling-Hammond, L. (2006). Constructing 21st-century teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 57(3), 300–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, D., Jindal-Snape, D., Digby, R., Howe, A., Collier, C., & Hay, P. (2014). The roles and development needs of teachers to promote creativity: A systematic review of literature. Teaching and Teacher Education, 41, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L., Zhu, G., Li, G., Xu, Z., Rutter, A., & Rivera, H. (2018). Student teachers’ emotions, dilemmas, and professional identity formation amid the teaching practicums. Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 27(6), 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durnali, M., Orakci, Ş., & Khalili, T. (2023). Fostering creative thinking skills to burst the effect of emotional intelligence on entrepreneurial skills. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 47, 101200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echegoyen Sanz, Y., & Martín Ezpeleta, A. (2021). Creativity and ecofeminism in teacher training. Qualitative analysis of digital stories. In Profesorado (Vol. 25, pp. 23–44). Grupo de Investigacion FORCE. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emirbayer, M. (1997). Manifesto for a relational sociology. American Journal of Sociology, 103(2), 281–317. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman, D. H., & Benjamin, A. C. (2006). Creativity and education: An American retrospective. Cambridge Journal of Education, 36(3), 319–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glăveanu, V. (2014). Revisiting the “Art Bias” in lay conceptions of creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 26(1), 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glăveanu, V. (2020). A sociocultural theory of creativity: Bridging the social, the material, and the psychological. Review of General Psychology, 24(4), 335–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glăveanu, V. (2021). Creativity. In A very short introduction (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, B. C., Sawyers, J. K., & DeBord, K. B. (1989). Teachers’ creativity, playfulness, and style of interaction with children. Creativity Research Journal, 2(1–2), 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilford, J. P. (1950). Creativity. American Psychologist, 5(9), 444–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, W., & Abdrahim, N. A. (2023). The role of teachers’ creativity in higher education: A systematic literature review and guidance for future research. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 48, 101302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Torrano, D., & Ibrayeva, L. (2020). Creativity and education: A bibliometric mapping of the research literature (1975–2019). Thinking Skills and Creativity, 35, 100625. [Google Scholar]

- Hickey, M., & Webster, P. (2001). Creative thinking in music. Music Educators Journal, 88(1), 19–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hlas, A. C., & Hlas, C. S. (2024). The creative abilities of preservice world language educators. Foreign Language Annals, 57(3), 747–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, J., Day, C., & Greene, B. (2018). The construction of early career teachers’ identities: Coping or managing? Teacher Development, 22(2), 249–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Y., & Yang, Y. (2024). Early childhood preservice teachers’ beliefs of creativity, creative individuals and creative environment: Perspectives from China. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 51, 101441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y., Oubibi, M., Chen, S., Yin, Y., & Zhou, Y. (2022). Pre-service teachers’ emotional experience: Characteristics, dynamics and sources amid the teaching practicum. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 968513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jokikokko, K., & Uitto, M. (2017). The significance of emotions in Finnish teachers’ stories about their intercultural learning. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 25(1), 15–29. [Google Scholar]

- Kanematsu, H., & Barry, D. M. (2016). Creativity and Its Importance for Education. In STEM and ICT education in intelligent environments (Vol. 91). Intelligent Systems Reference Library. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Katz-Buonincontro, J., Hass, R., Kettler, T., Tang, L. M., & Hu, W. (2020a). Partial measurement invariance of beliefs about teaching for creativity across U.S. and Chinese educators. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 91(2), 563–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz-Buonincontro, J., Hass, R. W., & Perignat, E. (2020b). Measuring beliefs about teaching for creativity. Teachers College Record, 122, 22. [Google Scholar]

- Katz-Buonincontro, J., Perignat, E., & Hass, R. W. (2020c). Conflicted epistemic beliefs about teaching for creativity. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 36, 100651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, J. C., & Beghetto, R. A. (2009). Beyond big and little: The four C model of creativity. Review of General Psychology, 13(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufman, J. C., Glǎveanu, V. P., & Baer, J. (2017). Creativity across different domains: An expansive approach. In J. C. Kaufman, V. Glăveanu, & J. Baer (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of creativity across domains (pp. 3–7). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, D. J., Bae, S. C., Choi, S. H., Kim, H. J., & Lim, W. (2019). Creative character education in mathematics for prospective teachers. Sustainability, 11(6), 1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimhi, Y., & Geronik, L. (2019). Creativity promotion in an excellence program for preservice teacher candidates. Journal of Teacher Education, 71(5), 505–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondrashova, L. V., Kondrashov, M. M., Chuvasova, N. O., Kalinichenko, N. A., & Deforzh, H. V. (2020). Development of creative potential of future teachers. Revista Educação & Formação, 5(3), e3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurok, V., Kurok, R., Burchak, L., Burchak, S., & Khoruzhenko, T. (2023). Pedagogical conditions for developing the creativity of future teachers in the process of their professional training. Revista Amazonia Investiga, 12(69), 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, T., Çakmak, M., Gündüz, M., & Busher, H. (2015). Research on teaching practicum—A systematic review. European Journal of Teacher Education, 38(3), 392–407. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, I. R., & Kemple, K. (2014). Preservice teachers’ personality traits and engagement in creative activities as predictors of their support for children’s creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 26(1), 82–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C. S., & Wu, R. Y. W. (2016). Effects of web-based creative thinking teaching on students’ creativity and learning outcome. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 12(6), 1675–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S. C., & Lin, H.-s. (2013). Primary teachers’ beliefs about scientific creativity in the classroom context. International Journal of Science Education, 36(10), 1551–1567. [Google Scholar]

- Marquis, E., & Henderson, A. (2015). Teaching creativity across disciplines at Ontario universities. Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 45, 148–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCormack, A., Gore, J., & Thomas, K. (2006). Early career teacher profesional learning. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 34(1), 95–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullet, D. R., Willerson, A., Lamb, K. N., & Kettler, T. (2016). Examining teacher perceptions of creativity: A systematic review of the literature. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 21, 9–30. [Google Scholar]

- Nerubasska, A., & Maksymchuk, B. (2020). The Demarkation of creativity, talent and genius in humans: A systemic aspect. Postmodern Openings, 11(2), 240–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newton, L., & Beverton, S. (2012). Pre-service teachers’ conceptions of creativity in elementary school English. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 7, 165–176. [Google Scholar]

- Nickerson, R. S. (1999). Enhancing creativity. In R. Sternberg (Ed.), Handbook of creativity (pp. 392–430). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaou, E. (2024). Encouraging creativity through music improvisation activities: Pre-service primary general teacher-students’ reflections and beliefs. International Journal of Music Education, 42(3), 461–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, K. E. (2008). “You choose to care”: Teachers, emotions and professional identity. Teaching and Teacher Education, 24(1), 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paek, S. H., & Sumners, S. E. (2019). The indirect effect of teachers’ creative mindsets on teaching creativity. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 53, 298–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, A., Toboso, S., Acha, A., & Cerrada, C. (2023). La performance como invitación al juego. Una reflexión desde la práctica sobre su utilidad en la formación inicial del profesorado de educación infantil. Arte, Individuo y Sociedad Avance en Línea, 35(2), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S. J. (2023). Testing the effects of a TRIZ invention instruction program on creativity beliefs, creativity, and invention teaching self-efficacy. Education and Information Technologies, 28(10), 12883–12902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patston, T. J., Kaufman, J. C., Cropley, A. J., & Marrone, R. (2021). What is creativity in education? A qualitative study of international curricula. Journal of Advanced Academics, 32(2), 207–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patston, T. P., Cropley, D. H., Marrone, R. L., & Kaufman, J. C. (2018). Teacher implicit beliefs of creativity: Is there an arts bias? Teaching and Teacher Education, 75, 366–374. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification (Vol. 1). American Psychological Association; Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Plucker, J. A., Beghetto, R. A., & Dow, G. T. (2004). Why isn’t creativity more important to educational psychologists? Potentials, pitfalls, and future directions in creativity research. Educational Psychologist, 39, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhodes, M. (1961). An analysis of creativity. The Phi Delta Kappan, 42(7), 305–310. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20342603 (accessed on 30 September 2024).

- Rivera Maulucci, M. S. (2013). Emotions and positional identity in becoming a social justice science teacher: Nicole’s story. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 50(4), 453–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runco, M. A., & Jaeger, G. J. (2012). The standard definition of creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 24(1), 92–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San, I. (2004). Sanat ve eğitim. Ütopya Yayinevi. [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer, R. K., & DeZutter, S. (2009). Distributed creativity: How collective creations emerge from collaboration. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 3(2), 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawyer, R. K., & Heriksen, D. (2024). Explaining Creativity. In The science of human innovation (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, J., Klusmann, U., Lüdtke, O., Möller, J., & Kunter, M. (2017). What makes good and bad days for beginning teachers? A diary study on daily uplifts and hassles. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 48, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, R. (2010). Creativity and education. Creative Education, 1, 166–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shkabarina, M., Verbytska, K., Vitiuk, V., Shemchuk, V., & Saleychuk, E. (2020). Development of pedagogical creativity of future teachers of primary school by means of innovative education technologies. Revista Romaneasca Pentru Educatie Multidimensionala, 12(4), 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steadman, S. (2021). Conflict, transition and agency: Reconceptualising the process of learning to teach. Teaching and Teacher Education, 107, 103475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, R. J., & Lubart, T. I. (1998). The concept of creativity: Prospects and paradigms. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Handbook of creativity (pp. 3–15). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres Carceller, A. (2021). La cocreación como medio de aprendizaje cooperativo. Tercio Creciente, 129–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO & International Task Force on Teachers for Education 2030. (2024). Global report on teachers: Addressing teacher shortages and transforming the profession. UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- Vedenpää, I., & Lonka, K. (2014). Teachers’ and teacher students’ conceptions of learning and creativity. Creative Education, 5, 1821–1833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, T., & Kunter, M. (2020). “Reality Shock” of beginning teachers? Changes in teacher candidates’ emotional exhaustion and constructivist-oriented beliefs. Journal of Teacher Education, 71(3), 292–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]