Making Challenging Social Studies Texts Accessible: An Intervention

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Scaffolding Reading Instruction

1.2. Scaffolding Social Studies Texts—An Intervention

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Assessments

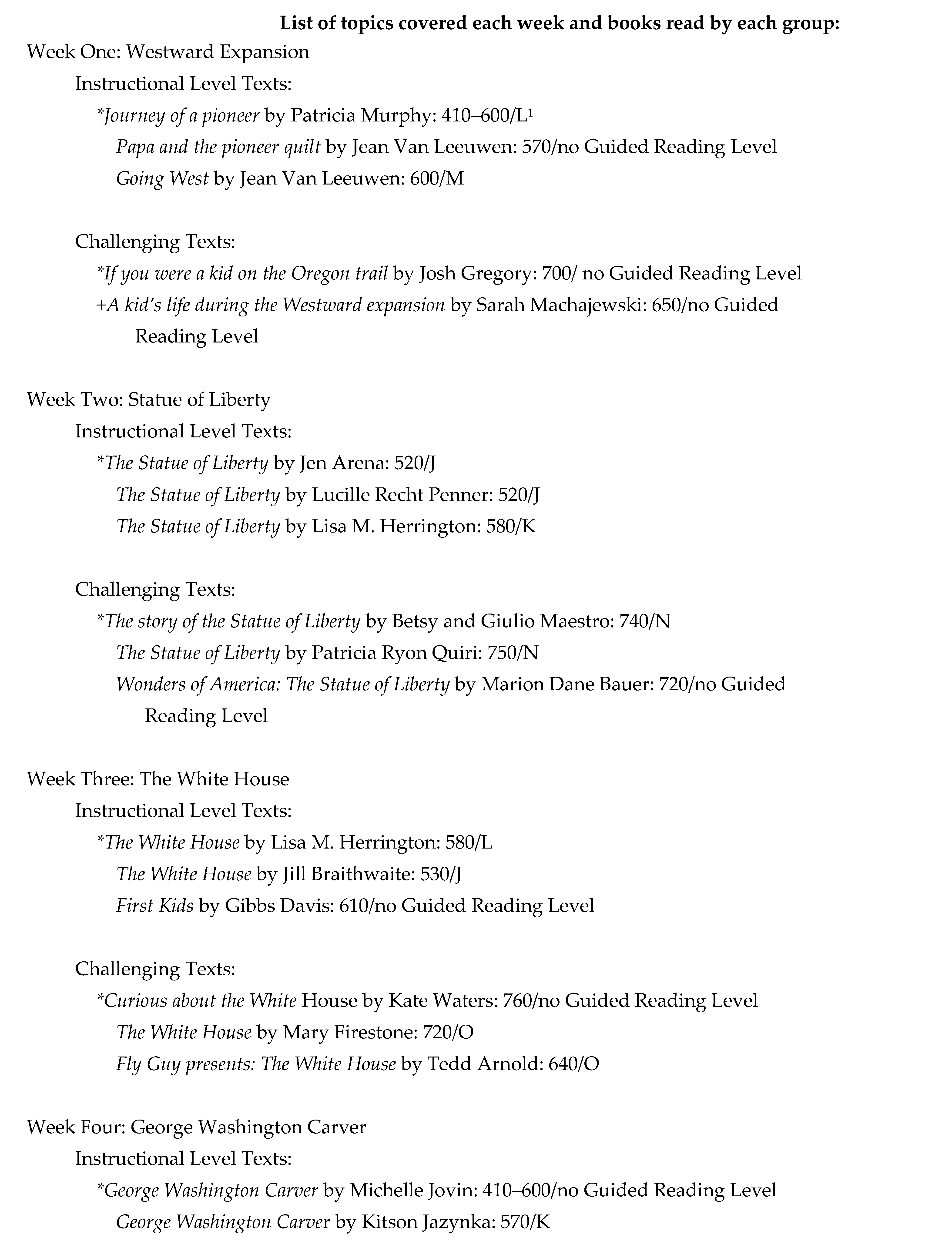

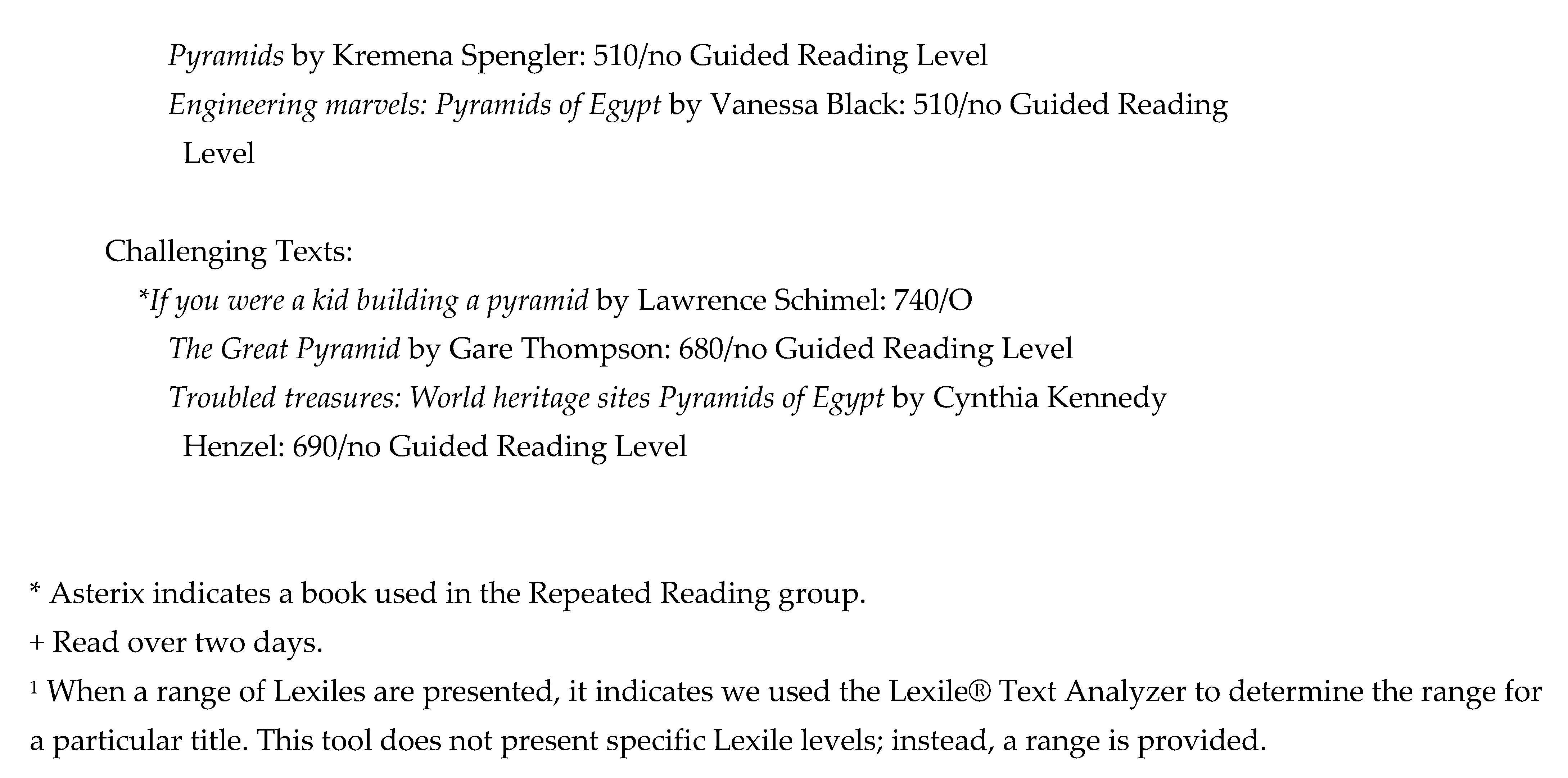

2.3. Instructional Materials

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Allington, R. L., McCuiston, K., & Billen, M. (2015). What research says about text complexity and learning to read. The Reading Teacher, 68, 491–501. [Google Scholar]

- Applegate, M. D., Applegate, A. J., & Modla, V. B. (2009). “She’s my best reader; she just can’t comprehend”: Studying the relationship between fluency and comprehension. The Reading Teacher, 62, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betts, E. A. (1946). Foundations of reading instruction: With emphasis on differentiated guidance (4th ed.). American Book Company. [Google Scholar]

- Cervetti, G. N., & Hiebert, E. H. (2015). The sixth pillar of reading instruction: Knowledge development. The Reading Teacher, 68, 548–551. [Google Scholar]

- Chall, J. S. (1995). Stages of reading development (2nd ed.). Harcourt Brace. [Google Scholar]

- Chomsky, C. (1976). After decoding: What? Language Arts, 53, 288–296. [Google Scholar]

- Dreher, M. J., & Kletzien, S. B. (2020). “I don’t just want to read, I want to learn something”: Best practices for using informational texts to build young children’s conceptual knowledge. In M. R. Kuhn, & M. J. Dreher (Eds.), Developing conceptual knowledge through oral and written language (pp. 35–57). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Duke, N. K., Halvorsen, A., Strachan, S. L., Kim, J., & Konstantopoulos, S. (2021). Putting PjBL to the test: The impact of project-based learning on second graders’ social studies and literacy learning and motivation in low-SES school settings. American Educational Research Journal, 58, 160–200. [Google Scholar]

- Fountas, I. C., & Pinnell, G. S. (2005). Leveled books, K-8: Matching text to readers for effective teaching. Heinemann. [Google Scholar]

- Hiebert, E. H., Scott, J. A., Castaneda, R., & Spichtig, A. (2019). An analysis of the features of words that influence vocabulary difficulty. Education Sciences, 9, 24. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, J. R., Schiller, E., Blackorby, J., Thayer, S. K., & Tilly, W. D. (2013). Responsiveness to intervention in reading: Architecture and practices. Learning Disability Quarterly, 36, 36–46. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, M. R. (2020). Whole class or small group fluency instruction: A tutorial of four effective approaches. Education Sciences: Special Issue Reading Fluency, 10, 145. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/journal/education/special_issues/reading_fluency (accessed on 20 January 2019).

- Kuhn, M. R., & Levy, L. (2015). Developing fluent readers: Teaching fluency as a foundational skill. The essential PK-2 literacy library. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, M. R., Schwanenflugel, P. J., & Meisinger, E. B. (2010). Aligning theory and assessment of reading fluency: Automaticity, prosody, and definitions of fluency. Invited review of the literature. Reading Research Quarterly, 45, 232–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, M. R., & Stahl, S. (2003). Fluency: A review of developmental and remedial practices. The Journal of Educational Psychology, 95, 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Leslie, L., & Caldwell, J. (1995). Qualitative reading inventory-II. Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Leslie, L., & Caldwell, J. S. (2016). Qualitative reading inventory-6. Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- McKenna, M. C., & Kear, D. J. (1990). Measuring attitude toward reading: A new tool for teachers. The Reading Teacher, 43, 626–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MetaMetrics. (2019). Look up a book’s measure. Available online: https://lexile.com/parents-students/find-books-at-the-right-level/lookup-a-books-measure/ (accessed on 20 January 2019).

- National Governors Association Center for Best Practices & Council of Chief State School Officers. (2010). Common core state standards for English language arts & literacy in history/social studies, science, and technical subjects. [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea, L. J., Sindelar, P. T., & O’Shea, D. (1985). The effects of repeated readings and attentional cues on reading fluency and comprehension. Journal of Reading Behavior, 17, 129–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, P. M., Miller, B. W., & Anderson, R. C. (2020). What does discussion add to reading for conceptual learning? In M. R. Kuhn, & M. J. Dreher (Eds.), Developing conceptual knowledge through oral and written language (pp. 58–75). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson, P. D., Palincsar, A. S., Biancarosa, G., & Berman, A. I. (Eds.). (2020). Reaping the rewards of the reading for understanding initiative. National Academy of Education. [Google Scholar]

- Recht, D. R., & Leslie, L. (1988). Effect of prior knowledge on good and poor readers’ memory of text. Journal of Educational Psychology, 80, 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Reutzel, D. R., & Fawson, P. C. (2022). Texts, texts, texts: A guide to analyze text elements for elementary students. Reading Teacher, 75, 495–504. [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan, T. (2020). Limiting children to books they can already read. American Educator, 44(2), 13. Available online: https://www.aft.org/ae/summer2020/shanahan (accessed on 5 August 2024).

- Stahl, K. A. D., & Garcia, G. E. (2022). Expanding reading comprehension in grades 3–6: Effective instruction for ALL students. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stahl, S. A., & Heubach, K. (2005). Fluency-oriented reading instruction. Journal of Literacy Research, 37, 25–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taboada-Barber, A., Buehl, M. M., Kidd, J. K., Sturtevant, E. G., Nuland, L. R., & Beck, J. (2015). Reading engagement in social studies: Exploring the role of a social studies literacy intervention on reading comprehension, reading self-efficacy, and engagement in middle school students with different language backgrounds. Reading Psychology, 36, 31–85. [Google Scholar]

- Torgesen, J. K., Wagner, R. K., & Rashotte, C. A. (2012). Test of word reading efficiency (2nd ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes, revised edition. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wexler, J., Vaughn, S., Roberts, G., & Denton, C. A. (2010). The efficacy of repeated reading and wide reading practice for high school students with severe reading disabilities. Learning Disabilities Research and Practice, 25, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wright, T. S., Cervetti, G. N., Wise, C., & McClung, N. A. (2022). The impact of knowledge-building through conceptually-coherent read alouds on vocabulary and comprehension. Reading Psychology, 43, 70–84. [Google Scholar]

| Text Complexity Grade Band in the Standards | Old Lexile Ranges | Lexile Ranges Aligned to CCR Expectations |

|---|---|---|

| K-1 | N/A | N/A |

| 2–3 | 450–725 | 450–790 |

| 4–5 | 645–845 | 770–980 |

| 6–8 | 860–1010 | 955–1155 |

| 9–10 | 960–1115 | 1080–1305 |

| 11-CCR | 1070–1220 | 1215–1355 |

| Monday | Wednesday | Friday | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wide Reading “Instructional level” texts * | Text #1 Echo reading | Text #2 Echo reading | Text #3 Echo reading |

| Repeated Reading “Instructional level” text | Text #1 Echo reading | Text #1 Choral reading | Text #1 Partner reading |

| Wide Reading “Challenging” texts ** | Text #1 Echo reading | Text #2 Echo reading | Text #3 Echo reading |

| Repeated Reading “Challenging” texts | Text #1 Echo reading | Text #1 Choral reading | Text #1 Partner reading |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kuhn, M.R.; Pigozzi, G.; Zhou, S.; Dahlgren, R. Making Challenging Social Studies Texts Accessible: An Intervention. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 389. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030389

Kuhn MR, Pigozzi G, Zhou S, Dahlgren R. Making Challenging Social Studies Texts Accessible: An Intervention. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(3):389. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030389

Chicago/Turabian StyleKuhn, Melanie R., Grace Pigozzi, Shuqi Zhou, and Robert Dahlgren. 2025. "Making Challenging Social Studies Texts Accessible: An Intervention" Education Sciences 15, no. 3: 389. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030389

APA StyleKuhn, M. R., Pigozzi, G., Zhou, S., & Dahlgren, R. (2025). Making Challenging Social Studies Texts Accessible: An Intervention. Education Sciences, 15(3), 389. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030389