The Relationship Between Student Well-Being and Teacher–Student and Student–Student Relationships: A Longitudinal Approach Among Secondary School Students in Switzerland

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Student Well-Being

1.2. Teacher–Student Relationships

1.3. Student–Student Relationships

1.4. Linking Teacher–Student Relationships and Student–Student Relationships

1.5. The Present Study

- (1)

- How do StudWB, closeness and conflict in TSRs, and cohesion in SSRs interact with each other over time?

- (2)

- How are closeness and conflict in TSRs and cohesion in SSRs related over time?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Measures

2.1.1. Student Well-Being

2.1.2. Teacher–Student Relationships

2.1.3. Student–Student Relationships

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics, Bivariate Correlations, Multivariate Normality Testing, and Multicollinearity

3.2. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.3. Intraclass Correlation

3.4. Measurement Invariance

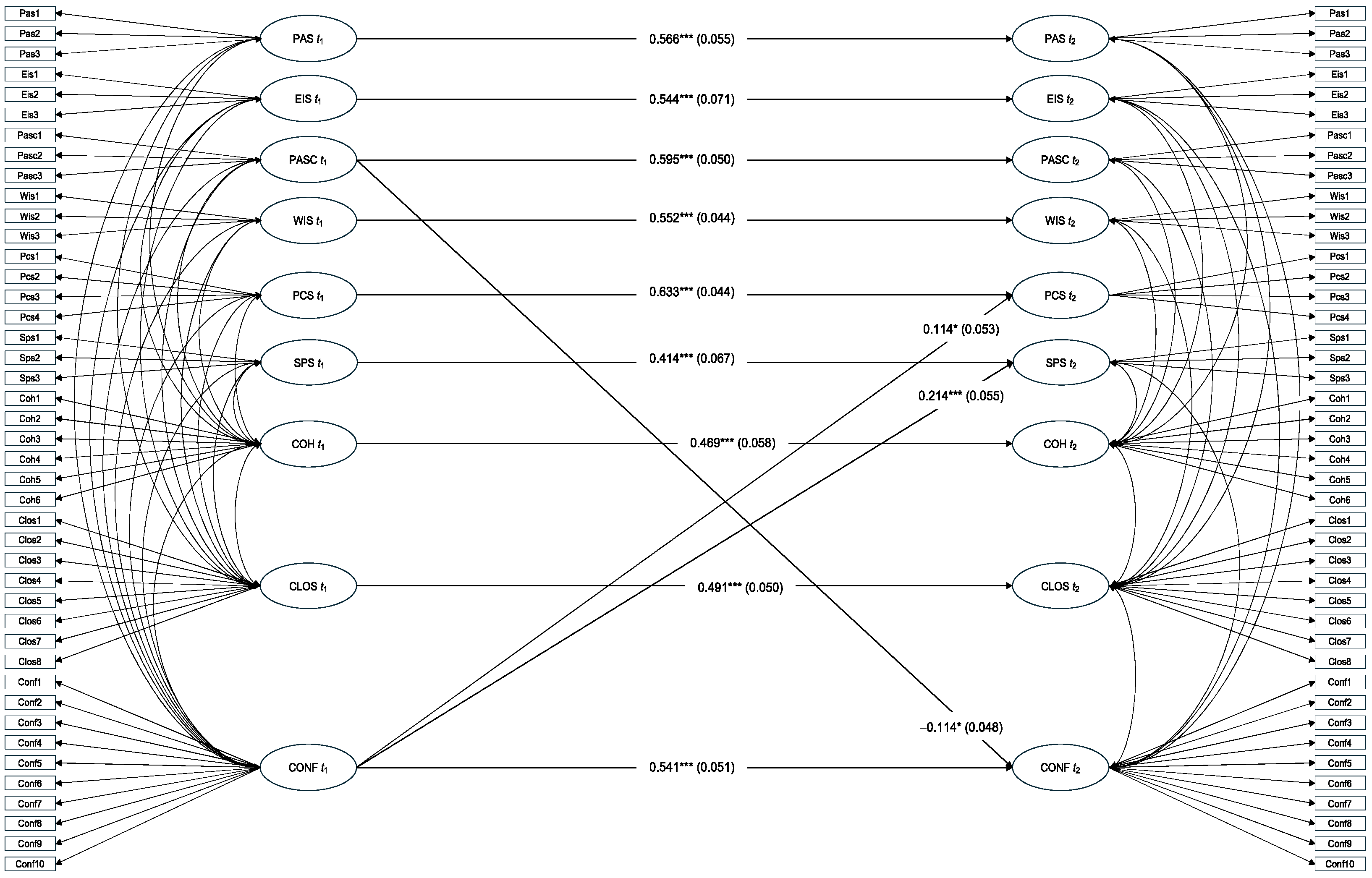

3.5. Structural Equation Models

3.5.1. Positive StudWB Dimensions, TSR, and SSR

3.5.2. Negative StudWB Dimensions, TSR, and SSR

3.5.3. TSRs and SSRs

4. Discussion

4.1. Autoregressive Effects

4.2. Cross-Lagged Effects Between StudWB, Closeness (TSR), and Cohesion (SSR)

4.3. Cross-Lagged Effects Between StudWB and Conflict (TSR)

4.4. Cross-Lagged Effects Between Conflict (TSR) and Cohesion (SSR)

4.5. Strengths, Limitations, and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| StudWB | Student well-being |

| TSR | Teacher–student relationship |

| SSR | Student–student relationship |

References

- Abuhassna, H., Busalim, A. H., Mamman, B., Yahaya, N., Megat Zakaria, M. A. Z., Al-Maatouk, Q., & Awae, F. (2022). From student’s experience: Does E-learning course structure influenced by learner’s prior experience, background knowledge, autonomy, and dialogue. Contemporary Educational Technology, 14(1), 7–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akaike, H. (1973). Information theory and an extension of the maximum likelihood principle. In B. N. Petrov, & F. Csàki (Eds.), Proceedings of the 2nd international symposium on information theory (pp. 267–281). Akadémiai Kiàdo. [Google Scholar]

- Ames, C. (1992). Classrooms: Goals, structures, and student motivation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 84(3), 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amodio, D. M., & Showers, C. J. (2005). ‘Similarity breeds liking’ revisited: The moderating role of commitment. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 22(6), 817–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakadorova, O., & Raufelder, D. (2018). The essential role of the teacher-student relationship in students’ need satisfaction during adolescence. Journal of Applied Development Psychology, 58(1), 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J. A., Grant, S., & Morlock, L. (2008). The teacher-student relationship as a developmental context for children with internalizing or externalizing behavior problems. School Psychology Quarterly, 23(1), 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1971). Social learning theory. General Learning Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (1993). Perceived self-efficacy in cognitive development and functioning. Educational Psychologist, 28(2), 117–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartko, J. J. (1966). The intraclass correlation coefficient as a measure of reliability. Psychological Reports, 19(1), 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R. F., Bratslavsky, E., Finkenauer, C., & Vohs, K. D. (2001). Bad is stronger than good. Review of General Psychology, 5(4), 323–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birch, S. H., & Ladd, G. W. (1997). The teacher–child relationship and children’s early school adjustment. Journal of School Psychology, 35(1), 61−79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BKD. (2022). Lehrplan für die Volksschule des Kantons Bern. Gesamtausgabe. Erziehungsdirektion des Kantons Bern. Available online: https://be.lehrplan.ch/downloads.php (accessed on 23 March 2024).

- Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Volume I. Attachment. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32(7), 513–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (2006). The bioecological model of human development. In R. M. Lerner, & W. Damon (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development (6th ed., pp. 793–828). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, B. B., & Larson, J. (2009). Peer relationships in adolescence. In R. M. Lerner, & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology: Contextual influences on adolescent development (3rd ed., pp. 74–103). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester, D., & Furman, W. (1987). The development of companionship and intimacy. Child Development, 58(4), 1101–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bukowski, M. B., Hoza, B., & Boivin, M. (1993). Popularity, friendship, and emotional adjustment during early adolescence. New Direction for Child Development, 60, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukowski, W. M., Laursen, B., & Rubin, K. H. (2018). Peer relations: Past, present, and promise. In W. M. Bukowski, B. Laursen, & K. H. Rubin (Eds.), Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups (2nd ed., pp. 3–20). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bush, E. S. (2005). Peer rejection, negative peer treatment, and school adjustment: Self-concept and classroom engagement as mediating processes. Journal of School Psychology, 43(5), 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, B. M. (1998). Structural equation modeling with LISREL, PRELIS and SIMPLIS: Basic concepts, applications and programming. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Beyers, W., Boone, L., Deci, E. L., Van der Kaap-Deeder, J., Duriez, B., Lens, W., Matos, L., Mouratidis, A., Ryan, R. M., Sheldon, K. M., Soenens, B., Van Petegem, S., & Verstuyf, J. (2015). Basic psychological need satisfaction, need frustration, and need strength across four cultures. Motivation and Emotion, 39(2), 216–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 14(3), 464–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J., Jiang, H., Justice, L. M., Lin, T.-J., Purtell, K. M., & Ansari, A. (2020). Influences of teacher–child relationships and classroom social management on child-perceived peer social experiences during early school years. Frontier in Psychology, 11, 586991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(2), 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelius-White, J. (2007). Learner-centered teacher-student relationships are effective: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 113–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, S., Ntoumanis, N., & Bartholomew, K. J. (2015). Predicting the brighter and darker sides of interpersonal relationships: Does psychological need thwarting matter? Motivation and Emotion, 39(1), 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DBK. (2015). Lehrplan für die Volksschule. Gesamtausgabe. Departement für Bildung und Kultur des Kantons Solothurn. Available online: https://so.lehrplan.ch/downloads.php (accessed on 23 March 2024).

- De Fraine, B., Van Landeghem, G., Van Damme, J., & Onghena, P. (2005). An analysis of well-being in secondary school with multilevel growth curve models and multilevel multi-variate models. Quality and Quantity, 39(1), 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wit, D. J., Karioja, K., Rye, B. J., & Shain, M. (2011). Perceptions of declining classmate and teacher support following the transition to high school: Potential correlates of increasing student mental health difficulties. Psychology in the Schools, 48(6), 556–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95(3), 542–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, E., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Very happy people. Psychological Science, 13(1), 81–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doumen, S., Verschueren, K., Buyse, E., Germeijs, V., Luyckx, K., & Soenens, B. (2008). Reciprocal relations between teacher-child conflict and aggressive behavior in kindergarten: A three-wave longitudinal study. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 37(3), 588–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durot, C. (2003). A komogorov-type test for monotonicity of regression. Statistics & Probability Letters, 63(4), 425–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J. S., Lord, S., & Midgley, C. (1991). What are we doing to early adolescents? The impact of educational contexts on early adolescents. American Journal of Education, 99, 521–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, J. S., & Roeser, R. W. (2009). Schools, academic motivation, and stage-environment fit. In R. M. Lerner, & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology: Individual bases of adolescent development (pp. 404–434). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles, J. S., & Roeser, R. W. (2011). Schools as developmental contexts during adolescence. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21(1), 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EDK. (2023). Lower secondary level. IDES Information and Documentation Centre. Available online: https://www.edk.ch/en/education-system-ch/compulsory/lower-secondary?set_language=en (accessed on 23 March 2024).

- Endedijk, H. M., Breeman, L. D., van Lissa, C. J., Hendrickx, M. M. H. G., den Boer, L., & Mainhard, T. (2021). The teacher’s invisible hand: A meta-analysis of the relevance of teacher–Student relationship quality for peer relationships and the contribution of student behavior. Review of Educational Research, 92(3), 370–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enders, C. K. (2010). Applied missing data analysis. The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity, youth and crisis. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Finch, J. F., Okun, M. A., Pool, G. J., & Ruehlman, L. S. (1999). A comparison of the influence of conflictual and supportive social interactions on psychological distress. Journal of Personality, 67(4), 581–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flook, L., Repetti, R., & Ullman, J. B. (2005). Classroom social experiences as predictors of academic performance. Developmental Psychology, 41(2), 319−327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Moya, I. (2020). The importance of connectedness in student-teacher relationships. Insights from the teacher connectedness project. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Garn, A., & Shen, B. (2015). Physical self-concept and basic psychological needs in exercise: Are there reciprocal effects? International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 13(2), 169–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goetz, T., Lüdtke, O., Nett, U. E., Keller, M. M., & Lipnevich, A. A. (2013). Characteristics of teaching and students’ emotions in the classroom: Investigating differences across domains. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 38(4), 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogol, K., Brunner, M., Martin, R., Preckel, F., & Goetz, T. (2017). Affect and motivation within and between school subjects: Development and validation of an integrative structural model of academic self-concept, interest, and anxiety. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 49(3), 46–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, A., Powell, M. A., & Truscott, J. (2016). Facilitating student well-being: Relationships do matter. Educational Research, 58(4), 366–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunnell, K. E., Crocker, P. R. E., Wilson, P. M., Mack, D. E., & Zumbo, B. D. (2013). Psychological need satisfaction and thwarting: A test of basic psychological needs theory in physical activity contexts. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 14(5), 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, M., Tomás, J.-M., Romero, I., & Barrica, J.-M. (2017). Perceived social support, school engagement and satisfaction with school. Revista de Psicodidáctica (English ed.), 22(2), 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2001). Early teacher-child relationships and the trajectory of children’s school outcomes through eighth grade. Child Development, 72(2), 625–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, A. (2000). Mixed emotions: Teachers’ perceptions of their interactions with students. Teaching and Teacher Education, 16(8), 811–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harks, M., & Hannover, B. (2017). Sympathiebeziehungen unter peers im klassenzimmer: Wie gut wissen lehrpersonen bescheid? [Sympathy-based peer interactions in the classroom: How well do teachers know them?]. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaften/Journal of Educational Research, 20(3), 425–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hascher, T. (2003). Well-being in school: Why students need social support. In P. Mayring, & C. von Rhöneck (Eds.), Learning emotions—The influence of affective factors on classroom learning (pp. 127–142). Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Hascher, T. (2004). Schule positiv erleben. Ergebnisse und erkenntnisse zum wohlbefinden von schülerinnen und schülern. Haupt Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Hascher, T. (2007). Exploring students’ well-being by taking a variety of looks into the classroom. Hellenic Journal of Psychology, 4, 331–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hascher, T. (2010). Wellbeing. In P. Peterson, E. Baker, & B. McGaw (Eds.), International encyclopedia of education (pp. 732–738). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickx, M. M. H. G., Mainhard, T., Boor-Klip, H. J., & Brekelmans, M. (2017a). Teacher liking as an affective filter for the association between student behavior and peer status. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 49, 250–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrickx, M. M. H. G., Mainhard, T., Oudman, S., Boor-Klip, H. J., & Brekelmans, M. (2017b). Teacher behavior and peer liking and disliking: The teacher as a social referent for peer status. Journal of Educational Psychology, 109(4), 546–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessischer Referenzrahmen Schulqualität (HRS). (2012). Dokumentation der Fragebogen [unveröffentlichte interne skalendokumentation]. Institut für Qualitätsentwicklung. [Google Scholar]

- Hoferichter, F., & Raufelder, D. (2022). Kann erlebte Unterstützung durch Lehrkräfte schulische Erschöpfung und stress bei Schülerinnen und Schülern abfedern? [Can perceived teacher support buffer school exhaustion and stress in students?]. Zeitschrift für Pädagogische Psychologie/German Journal of Educational Psychology, 36(1–2), 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holopainen, L., Lappalainen, K., Junttila, N., & Savolainen, H. (2012). The role of social competence in the psychological wellbeing of adolescents in secondary education. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 56(2), 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structural analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, C., Gerullis, A., Gebhardt, M., & Schwab, S. (2018). The impact of social referencing on social acceptance of children with disabilities and migrant background: An experimental study in primary school settings. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 33(2), 269–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J. N., Cavell, T. A., & Willson, V. (2001). Further support for the developmental significance of the quality of the teacher–student relationship. Journal of School Psychology, 39(4), 289–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J. N., & Chen, Q. (2011). Reciprocal effects of student-teacher and student-peer relatedness: Effects on academic self efficacy. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 32(5), 278–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hughes, J. N., & Im, M. H. (2016). Teacher-student relationship and peer disliking and liking across Grades 1–4. Child Development, 87(2), 593–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishiyama, F. I., & Chabassol, D. J. (1985). Adolescents’ fear of the social consequences of academic success as a function of age and sex. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 14(1), 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jagenow, D., Raufelder, D., & Eid, M. (2015). The development of socio-motivational dependency from early to middle adolescence. Frontiers in Psychology, 6(194), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, P. A., & Greenberg, M. T. (2009). The prosocial classroom: Teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Review of Educational Research, 79(1), 491–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiefer, S., Alley, K., & Ellerbrock, C. (2015). Teacher and peer support for young adolescents’ motivation, engagement and school belonging. RMLE Online, 38(8), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kincade, L., Cook, C., & Goerdt, A. (2020). Meta-analysis and common practice elements of universal approaches to improving student-teacher relationships. Review of Educational Research, 90(5), 710–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R. B. (2015). Sense of relatedness boosts engagement, achievement, and well-being: A latent growth model study. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 42, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiuru, N., Wang, M.-T., Salmela-Aro, K., Kannas, L., Ahonen, T., & Hirvonen, R. (2020). Transactional associations between adolescents’ interpersonal relationships, school well-being, and academic achievement during educational transitions. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49(5), 1057–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klima, T., & Repetti, R. L. (2008). Children’s peer relations and their psychological adjustment: Differences between close friendships and the larger peer group. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 54(2), 151–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kochenderfer-Ladd, B., & Pelletier, M. E. (2008). Teachers’ views and beliefs about bullying: Influences on classroom management strategies and students’ coping with peer victimization. Journal of School Psychology, 46(4), 431–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohne, J., Gallagher, N., Kirgil, Z. M., Paolillo, R., Padmos, L., & Karimi, F. (2019). The role of network structure and initial group norm distributions in norm conflict. In E. Deutschmann, J. Lorenz, L. G. Nadrin, D. Natalini, & A. F. X. Wilhelm (Eds.), Computational conflict research (pp. 113–140). Springer Open. [Google Scholar]

- Konu, A., Alanen, E., Lintonen, T., & Rimpelä, M. (2002). Factor structure of the school well-being model. Health Education Research, 17(6), 732–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koomen, H. M. Y., & Jellesma, F. C. (2015). Can closeness, conflict, and dependency be used to characterize students’ perceptions of the affective relationship with their teacher? Testing a new child measure in middle childhood. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 85(4), 479–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kornienko, O., & Santos, C. (2014). The effects of friendship network popularity on depressive symptoms during early adolescence: Moderation by fear of negative evaluation and gender. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(4), 541–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köller, O., Trautwein, U., Lüdtke, O., & Baumert, J. (2006). Zum Zusammenspiel von schulischer Leistung, Selbstkonzept und Interesse in der gymnasialen Bberstufe [On the interplay of academic achievement, self-concept, and interest in upper secondary schools]. Zeitschrift für Pädagogische Psychologie/German Journal of Educational Psychology, 20(1–2), 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuusi, A., Tuominen, H., Widlund, A., Korhonen, J., & Niemivirta, M. (2024). Lower secondary students’ perfectionistic profiles: Stability, transitions, and connections with well-being. Learning and Individual Differences, 110, 102419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladd, G. W., Birch, S. H., & Buhs, E. S. (1999). Children’s social and scholastic lives in kindergarten: Related spheres of influence? Child Development, 70(6), 1373–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress: Appraisal and coping. Springer Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- László, K., Andersson, F., & Galanti, M. (2019). School climate and mental health among Swedish adolescents: A multilevel longitudinal study. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1695–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehman, B. J., & Repetti, R. L. (2007). Bad days don’t end when the school bell rings: The lingering effects of negative school events on children’s mood, self-esteem, and perceptions of parent-child interaction. Social Development, 16(3), 596–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H., Cui, Y., & Chiu, M. M. (2018). The relationship between teacher support and students’ academic emotions: A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, R. J. A. (1988). A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 83(404), 1198–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, R. J. A., & Rubin, D. B. (2014). Statistical analysis with missing data. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Little, T. D. (2013). Longitudinal structural equation modelling. The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W., Mei, J., Tian, L., & Huebner, E. S. (2016). Age and gender differences in the relation between school-related social support and subjective well-being in school among students. Social Indicators Research, 125(3), 1065–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynch, M., & Chicchetti, D. (1997). Children’s relationships with adults and peers: An examination of elementary and junior high school students. Journal of School Psychology, 35(1), 81–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mainhard, T., Oudman, S., Hornstra, L., Bosker, R. J., & Goetz, T. (2018). Student emotions in class: The relative importance of teachers and their interpersonal relations with students. Learning and Instruction, 53(1), 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, H. W., Martin, A. J., Yeung, A. S., & Craven, R. G. (2017). Competence self-perceptions. In A. J. Elliot, C. S. Dweck, & D. S. Yeager (Eds.), Handbook of competence and motivation: Theory and application (2nd ed., pp. 85–115). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Martela, F., & Sheldon, K. (2019). Clarifying the concept of well-being: Psychological need satisfaction as the common core connecting eudaimonic and subjective well-being. Review of General Psychology, 23(4), 458–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, K. M., & Huebner, E. S. (2007). Peer victimization and prosocial experiences and emotional well-being of middle school students. Psychology in the Schools, 44(2), 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, F. J. (1951). The kolmogorov-smirnov test for goodness of fit. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 46(253), 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAuliffe, M. D., Hubbard, J. A., & Romano, L. J. (2009). The role of teacher cognition and behavior in children’s peer relations. Journal Abnormal Child Psychology, 37(5), 665–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEwen, B. S. (1998). Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. New England Journal of Medicine, 338(3), 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGraw, K. O., & Wong, S. P. (1996). Forming inferences about some intraclass correlation coefficients. Psychological Methods, 1(1), 30–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, S. H., & DeRosier, M. E. (2008). Teacher preference, peer rejection, and student aggression: A prospective study of transactional influence and independent contributions to emotional adjustment and grades. Journal of School Psychology, 46(6), 661−687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meredith, W., & Teresi, J. A. (2006). An essay on measurement and factorial invariance. Medical Care, 44(11), 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller-Lewis, L., Sawyer, A., Searle, A., Mittinty, M., Sawyer, M., & Lynch, J. (2014). Student-teacher relationship trajectories and mental health problems in young children. BMC Psychology, 2(1), 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moore, S. M., Diener, E., & Tan, K. (2018). Using multiple methods to more fully understand causal relations: Positive affect enhances social relationships. In E. Diener, S. Oishi, & L. Tay (Eds.), Handbook of well-being. DEF Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Morinaj, J., & Hascher, T. (2022). Wellbeing of primary and secondary school students in Switzerland: A longitudinal perspective. In R. McLellan, C. Faucher, & V. Simovska (Eds.), Wellbeing and schooling. Cross cultural and cross disciplinary perspectives (Vol. 4, pp. 67–86). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Morinaj, J., & Held, T. (2023). Stability and change in student well-being: A three-wave longitudinal person-centered approach. Personality and Individual Differences, 203, 112015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrow, M. T., Hubbard, J. A., Barhight, L. J., & Thomson, A. K. (2014). Fifth-grade children’s daily experiences of peer victimization and negative emotions: Moderating effects of sex and peer rejection. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 42(7), 1089–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murberg, T. A., & Bru, E. (2004). School-related stress and psychosomatic symptoms among Norwegian adolescents. School Psychology International, 25(3), 317–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2017). Mplus user’s guide (8th ed.). Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Newsom, J. T. (2015). Longitudinal structural equation modeling: A comprehensive introduction. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Nishina, A. (2012). Microcontextual characteristics of peer victimization experiences and adolescents’ daily well-being. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41(2), 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishina, A., & Juvonen, J. (2005). Daily reports of witnessing and experiencing peer harassment in middle school. Child Development, 76(2), 435–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, R. M. (2007). A caution regarding rules of thumb for variance inflation factors. Quality & Quantity, 41, 673–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2023). OECD Future of education and skills 2030. OECD learning compass 2030. OECD Publishing. Available online: https://issuu.com/oecd.publishing/docs/e2030-learning_compass_2030-concept_notes?fr=xKAE9_zU1NQ (accessed on 8 March 2024).

- Osterman, K. F. (2000). Students’ need for belonging in the school community. Review of Educational Research, 70(3), 323–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Östberg, V. (2003). Children in classrooms: Peer status, status distribution and mental well-being. Social Science and Medicine, 56(1), 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, P. D., Marsh, H. W., Morin, A. J., Seaton, M., & Van Zanden, B. (2015). If one goes up the other must come down: Examining ipsative relationships between math and English self-concept trajectories across high school. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 85(2), 172–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patalay, P., & Fitzsimons, E. (2016). Correlates of mental illness and wellbeing in children: Are they the same? Results from the UK millennium cohort study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 55(9), 771–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pianta, R. C. (1999). Enhancing relationships between children and teachers. American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta, R. C., Hamre, B., & Stuhlman, M. (2003). Relationships between teachers and children. In W. M. Reynolds, & G. E. Miller (Eds.), Handbook of psychology: Volume 7, Educational psychology (pp. 199–234). John Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta, R. C., Hamre, B. K., & Allen, J. P. (2012). Teacher-student relationships and engagement: Conceptualizing, measuring, and improving the capacity of classroom interactions. In S. L. Christenson, A. L. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 365–386). Springer Science + Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta, R. C., Steinberg, M. S., & Rollins, L. B. (1995). The first two years of school: Teacher–child relationships and deflections in children’s classroom adjustment. Development and Psychopathology, 7(2), 295–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietarinen, J., Soini, T., & Pyhältö, K. (2014). Students’ emotional and cognitive engagement as the determinants of well-being and achievement in school. International Journal of Educational Research, 67(3), 40–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, E., & Lee, P. D. (2003). Child well-being: A systematic review of the literature. Social Indicators Research, 61(1), 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portney, L. G., & Watkins, M. P. (2000). Foundations of clinical research: Applications to practice (2nd ed.). Prentice Hall Health. [Google Scholar]

- Preckel, F., Niepel, C., Schneider, M., & Brunner, M. (2013). Self-concept in adolescence: A longitudinal study on reciprocal effects of self-perceptions in academic and social domains. Journal of Adolescence, 36(6), 1165–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putwain, D. W., Loderer, K., Gallard, D., & Beaumont, J. (2020). School-related subjective well-being promotes subsequent adaptability, achievement, and positive behavioural conduct. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 90(1), 92–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quin, D. (2017). Longitudinal and contextual associations between teacher-student relationships and student engagement: A systematic review. Review of Educational Research, 87(2), 345–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raccanello, D., Vicentini, G., Trifiletti, E., & Burro, R. (2020). A rasch analysis of the school-related well-being (SRW) scale: Measuring well-being in the transition from primary to secondary school. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(1), 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ragelienė, T. (2016). Links of adolescents identity development and relationship with peers: A systematic literature review. Journal of the Canadian Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 25(2), 97–105. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, C. D. (2022). A framework for motivating teacher-student relationships. Educational Psychology Review, 34(4), 2061–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeser, R. W., Eccles, J. S., & Sameroff, A. J. (2000). School as a context of early adolescents’ academic and social-emotional development: A summary of research findings. The Elementary School Journal, 100(5), 443–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rook, K. S. (1984). The negative side of social interaction: Impact on psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46(5), 1097–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roorda, D. L., Jak, S., Zee, M., Oort, F. J., Koomen, H. M. Y., & Dowdy, E. (2017). Affective teacher–student relationships and students’ engagement and achievement: A meta-analytic update and test of the mediating role of engagement. School Psychology Review, 46(3), 239–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roorda, D. L., Koomen, H. M. Y., Spilt, J. L., & Oort, F. J. (2011). The influence of affective teacher-student relationships on students’ school engagement and achievement: A meta-analytic approach. Review of Educational Research, 81(4), 493–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roza, J. M. G., Frenzel, A. C., & Klassen, R. M. (2021). The teacher-class relationship A mixed-methods approach to validating a new scale. Zeitschrift für Pädagogische Psychologie, 36(1–2), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, K. H., Bukowski, W. M., & Laursen, B. (Eds.). (2009). Handbook of peer interactions, relationships, and groups. The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, K. H., Bukowski, W. M., & Parker, J. G. (2006). Peer interactions, relationships, and groups. In N. Eisenberg, W. Damon, & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Social, emotional, and personality development (6th ed., pp. 571–645). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Rutkowski, L., & Svetina, D. (2014). Assessing the hypothesis of measurement invariance in the context of large-scale international surveys. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 74(1), 31–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory. The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabol, T. J., & Pianta, R. C. (2012). Recent trends in research on teacher-child relationships. Attachment & Human Development, 14(3), 213–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A. J., Vaughn, B. E., Peceguina, I., Daniel, J. R., & Shin, N. (2014). Longitudinal stability of social competence indicators in a Portuguese sample: Q-sort profiles of social competence, measures of social engagement, and peer sociometric acceptance. Developmental Psychology, 50(3), 968–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satorra, A., & Bentler, P. M. (2001). A scaled difference chi-square test statistic for moment structure analysis. Psychometrika, 66(4), 507–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiefer, D., & van der Noll, J. (2017). The essentials of social cohesion: A literature review. Social Indicators Research, 132(2), 579–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A., Dirk, J., & Schmiedek, F. (2019). The importance of peer relatedness at school for affective well-being in children: Between- and within-person associations. Social Development, 28(4), 873–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwab, S., & Rossmann, P. (2020). Peer integration, teacher-student relationships and the association with depressive symptoms in secondary school students with and without special needs. Educational Studies, 46(3), 302–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, G. (1978). Estimating the dimension of a model. Annals of Statistics, 6(2), 461–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M. E. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shrout, P. E., & Fleiss, J. L. (1979). Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychological Bulletin, 86(2), 420–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siedlecki, K. L., Salthouse, T. A., Oishi, S., & Jeswani, S. (2014). The relationship between social support and subjective well-being across age. Social Indicators Research, 117(2), 561–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonsmeier, B. A., Peiffer, H., Flaig, M., & Schneider, M. (2020). Peer feedback improves students’ academic self-concept in higher education. Research in Higher Education, 61(1), 706–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiger, J. H. (2007). Understanding the limitations of global fit assessment in structural equation modeling. Personality and Individual Differences, 42(5), 893–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, H. S. (1953). The interpersonal theory of psychiatry. Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Thapa, A., Cohen, J., Guffey, S., & Higgins-D’Alessandro, A. (2013). A review of school climate research. Review of Educational Research, 83(3), 257–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobia, V., Greco, A., Steca, P., & Marzocchi, G. M. (2019). Children’s wellbeing at school: A multi-dimensional and multi-informant approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 20(3), 841–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomba, E., Belaise, C., Ottolini, F., Ruini, C., Bravi, A., Albieri, E., Rafanelli, C., Caffo, E., & Fava, G. A. (2010). Differential effects of well-being promoting and anxiety-management strategies in a non-clinical school setting. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 24(3), 326–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troop-Gordon, W., & Kuntz, K. J. (2013). The unique and interactive contributions of peer victimization and teacher-child relationships to children’s school adjustment. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41(7), 1191–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verschueren, K. (2015). Middle childhood teacher–child relationships: Insights from an attachment perspective and remaining challenges. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 2015(148), 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verschueren, K., & Koomen, H. M. Y. (2012). Teacher–child relationships from an attachment perspective. Attachment & Human Development, 14(3), 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Véronneau, M. H., Koestner, R. F., & Abela, J. R. (2005). Intrinsic need satisfaction and well-being in children and adolescents: An application of the self-determination theory. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 24(2), 280–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C., Hatzigianni, M., Shahaeian, A., Murray, E., & Harrison, L. J. (2016). The combined effects of teacher-child and peer relationships on children’s social-emotional adjustment. Journal of School Psychology, 59, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M., Brinkworth, M., & Eccles, J. (2013). Moderating effects of teacher-student relationship in adolescent trajectories of emotional and behavioral adjustment. Developmental Psychology, 49(4), 690–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, S., Puskar, K. R., & Ren, D. (2010). Relationships between depressive symptoms and perceived social support, self-esteem, & optimism in a sample of rural adolescents. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 31(9), 584–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westphal, A., Kretschmann, J., Gronostaj, A., & Vock, M. (2018). More enjoyment, less anxiety and boredom: How achievement emotions relate to academic self-concept and teachers’ diagnostic skills. Learning and Individual Differences, 62(1), 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitby, P. J. S., Ogilvie, C., & Mancil, G. R. (2012). A framework for teaching social skills to students with Asperger syndrome in the general education classroom. Journal on Developmental Disabilities, 18(1), 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widlund, A., Tuominen, H., & Korhonen, J. (2024). Motivational profiles in mathematics—Stability and links with educational and emotional outcomes. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 76, 102256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, G. M., & Clark, M. S. (1989). Providing help and desired relationship type as determinants of changes in moods and self-evaluations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(5), 722–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G., & Zhang, L. (2022). Longitudinal associations between teacher-student relationships and prosocial behavior in adolescence: The mediating role of basic need satisfaction. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(22), 14840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, Y., Wang, C., Zhu, Q., He, M., Havawala, M., Bai, X., & Wang, T. (2022). Parenting and teacher-student relationship as protective factors for Chinese adolescent adjustment during Covid-19. School Psychology Review, 51(2), 187–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, K.-H., & Bentler, P. M. (2008). Three likelihood-based methods for mean and covariance structure analysis with nonnormal missing data. Sociological Methodology, 30(1), 165–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., & Sun, J. (2011). The reciprocal relations between teachers’ perceptions of children’s behavior problems and teacher–child relationships in the first preschool year. The Journal of Genetic Psychology: Research and Theory on Human Development, 172(2), 176–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D., Du, X. F., Hau, K. T., Luo, H. F., Feng, P. T., & Liu, J. (2020). Teacher-student relationship and mathematical problem-solving ability: Mediating roles of self-efficacy and mathematical anxiety. Educational Psychology, 40(3), 473–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J., Chipuer, H. M., Hanisch, M., Creed, P. A., & McGregor, L. (2006). Relationships at school and stage-environment fit as resources for adolescent engagement and achievement. Journal of Adolescence, 29(6), 911−933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zullig, K. J., Huebner, E. S., & Patton, J. M. (2011). Relationships among school climate domains and school satisfaction. Psychology in the Schools, 48(2), 133–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | M | SD | ω | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PAS t1 | 4.28 | 1.04 | 0.80 | – | |||||||||||||||||

| 2. EIS t1 | 4.33 | 1.01 | 0.71 | 0.61 ** | – | ||||||||||||||||

| 3. PASC t1 | 4.31 | 1.02 | 0.77 | 0.34 ** | 0.25 ** | – | |||||||||||||||

| 4. WIS t1 | 3.29 | 1.42 | 0.81 | −0.14 ** | −0.09 * | −0.33 ** | – | ||||||||||||||

| 5. PCS t1 | 2.15 | 1.25 | 0.83 | −0.15 ** | −0.09 ** | −0.26 ** | 0.53 ** | – | |||||||||||||

| 6. SPS t1 | 1.67 | 0.97 | 0.78 | −0.21 ** | −0.13 ** | −0.14 ** | 0.27 ** | 0.38 ** | – | ||||||||||||

| 7. CLOS t1 | 3.28 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.38 ** | 0.42 ** | 0.18 ** | −0.12 ** | −0.15 ** | −0.14 ** | – | |||||||||||

| 8. CONF t1 | 1.95 | 0.94 | 0.94 | −0.26 ** | −0.20 ** | −0.13 ** | 0.20 ** | 0.26 ** | 0.19 ** | −0.06 | – | ||||||||||

| 9. COH t1 | 3.06 | 0.56 | 0.83 | 0.31 ** | 0.27 ** | 0.22 ** | −0.16 ** | −0.21 ** | −0.40 ** | 0.39 ** | −0.15 ** | – | |||||||||

| 10. PAS t2 | 4.06 | 1.10 | 0.82 | 0.53 ** | 0.40 ** | 0.25 ** | −0.07 | −0.12 ** | −0.13 ** | 0.25 ** | −0.23 ** | 0.26 ** | – | ||||||||

| 11. EIS t2 | 3.97 | 1.14 | 0.80 | 0.44 ** | 0.48 ** | 0.17 ** | −0.04 | −0.07 | −0.12 ** | 0.28 ** | −0.21 ** | 0.18 ** | 0.66 ** | – | |||||||

| 12. PASC t2 | 4.36 | 1.03 | 0.85 | 0.23 ** | 0.18 ** | 0.50 ** | −0.20 ** | −0.22 ** | −0.09 * | 0.11 ** | −0.16 ** | 0.18 ** | 0.34 ** | 0.30 ** | – | ||||||

| 13. WIS t2 | 3.45 | 1.46 | 0.82 | −0.11 ** | −0.12 ** | −0.16 ** | 0.49 ** | 0.42 ** | 0.22 ** | −0.12 ** | 0.14 ** | −0.04 | −0.09 * | −0.06 | −0.23 ** | – | |||||

| 14. PCS t2 | 2.28 | 1.34 | 0.81 | −0.09 * | −0.11 ** | −0.16 ** | 0.35 ** | 0.60 ** | 0.25 ** | −0.11 * | 0.24 ** | −0.09 * | −0.25 ** | −0.16 ** | −0.19 ** | 0.59 ** | – | ||||

| 15. SPS t2 | 1.81 | 1.08 | 0.82 | −0.14 ** | −0.07 | −0.13 ** | 0.21 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.39 ** | −0.06 | 0.28 ** | -0.15 ** | −0.20 ** | −0.11 ** | −0.13 ** | 0.30 ** | 0.48 ** | – | |||

| 16. CLOS t2 | 3.31 | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.25 ** | 0.28 ** | 0.15 ** | −0.07 | −0.11 ** | −0.11 ** | 0.49 ** | −0.10 * | 0.28 ** | 0.38 ** | 0.37 ** | 0.20 ** | −0.14 ** | −0.14 ** | −0.06 | – | ||

| 17. CONF t2 | 1.95 | 0.86 | 0.92 | −0.24 ** | −0.17 ** | −0.18 ** | 0.16 ** | 0.17 ** | 0.13 ** | −0.13 ** | 0.54 ** | −0.17 ** | −0.28 ** | −0.25 ** | −0.18 ** | 0.09 * | 0.21 ** | 0.19 ** | −0.24 ** | – | |

| 18. COH t2 | 3.01 | 0.55 | 0.84 | 0.23 ** | 0.19 ** | 0.15 ** | −0.14 ** | −0.19 ** | −0.26 ** | 0.17 ** | −0.18 ** | 0.40 ** | 0.33 ** | 0.23 ** | 0.28 ** | −0.19 ** | −0.19 ** | −0.31 ** | 0.35 ** | −0.15 ** | – |

| χ2(df) | CFI | TLI | SRMR | RMSEA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CFA Models StudWB | |||||

| Six-factor model | 296 (137) | 0.970 | 0.963 | 0.039 | 0.039 |

| Two-factor model | 1781 (151) | 0.697 | 0.656 | 0.097 | 0.120 |

| One-factor model | 3092 (152) | 0.453 | 0.384 | 0.141 | 0.160 |

| CFA Models TSR | |||||

| Two-factor model | 897 (134) | 0.915 | 0.902 | 0.090 | 0.090 |

| One-factor model | 3624 (135) | 0.609 | 0.557 | 0.215 | 0.191 |

| CFA Models SSR | |||||

| One-factor model | 50 (9) | 0.971 | 0.952 | 0.031 | 0.080 |

| Models | Overall Fit Indices | Model Comparison | Comparative Fit Indices | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | df | CFI | RMSEA | SRMR | Δχ2 | Δdf | ΔCFI | ΔRMSEA | ||

| Positive attitudes toward school | ||||||||||

| 1. Configural invariance | 0.00 | 0 | 1.00 | 0.000 | 0.000 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 2. Metric invariance | 0.81 | 2 | 1.00 | 0.000 | 0.013 | 2 vs. 1 | 0.81 (ns) | 2 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 3. Scalar invariance | 8.03 | 4 | 0.99 | 0.039 | 0.026 | 3 vs. 2 | 7.26 * | 2 | 0.003 | 0.039 |

| Enjoyment in school | ||||||||||

| 1. Configural invariance | 0.00 | 0 | 1.00 | 0.000 | 0.000 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 2. Metric invariance | 5.17 | 2 | 0.993 | 0.048 | 0.032 | 2 vs. 1 | 5.17 (ns) | 2 | 0.007 | 0.048 |

| 3. Scalar invariance | 33.36 | 4 | 0.936 | 0.104 | 0.059 | 3 vs. 2 | 34.63 *** | 2 | 0.057 | 0.056 |

| Positive academic self-concept | ||||||||||

| 1. Configural invariance | 0.00 | 0 | 1.00 | 0.000 | 0.000 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 2. Metric invariance | 0.21 | 2 | 1.00 | 0.000 | 0.010 | 2 vs. 1 | 0.33 (ns) | 2 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 3. Scalar invariance | 3.64 | 4 | 1.00 | 0.000 | 0.006 | 3 vs. 2 | 4.16 (ns) | 2 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Worries in school | ||||||||||

| 1.Configural invariance | 0.00 | 0 | 1.00 | 0.000 | 0.000 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 2. Metric invariance | 1.39 | 2 | 1.00 | 0.000 | 0.013 | 2 vs. 1 | 1.39 (ns) | 2 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 3. Scalar invariance | 21.70 | 4 | 0.983 | 0.081 | 0.034 | 3 vs. 2 | 24.23 *** | 2 | 0.017 | 0.081 |

| Physical complaints in school | ||||||||||

| 1.Configural invariance | 12.92 | 4 | 0.994 | 0.057 | 0.017 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 2. Metric invariance | 16.52 | 7 | 0.993 | 0.043 | 0.020 | 2 vs. 1 | 1.16 (ns) | 3 | 0.001 | 0.014 |

| 3. Scalar invariance | 20.60 | 10 | 0.992 | 0.040 | 0.023 | 3 vs. 2 | 1.91 (ns) | 3 | 0.001 | 0.003 |

| Social problems in school | ||||||||||

| 1.Configural invariance | 0.00 | 0 | 1.00 | 0.000 | 0.000 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 2. Metric invariance | 0.72 | 2 | 1.00 | 0.000 | 0.011 | 2 vs. 1 | 0.72 (ns) | 2 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| 3. Scalar invariance | 1.00 | 4 | 1.00 | 0.000 | 0.011 | 3 vs. 2 | 0.02 (ns) | 2 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Closeness | ||||||||||

| 1. Configural invariance | 217.46 | 34 | 0.961 | 0.092 | 0.041 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 2. Metric invariance | 239.65 | 41 | 0.958 | 0.088 | 0.048 | 2 vs. 1 | 11.85 (ns) | 7 | 0.003 | 0.004 |

| 3. Scalar invariance | 266.44 | 48 | 0.954 | 0.085 | 0.053 | 3 vs. 2 | 24.56 *** | 7 | 0.004 | 0.003 |

| Conflict | ||||||||||

| 1. Configural invariance | 204.74 | 70 | 0.975 | 0.055 | 0.025 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 2. Metric invariance | 218.62 | 79 | 0.975 | 0.053 | 0.027 | 2 vs. 1 | 3.70 (ns) | 9 | <0.001 | 0.002 |

| 3. Scalar invariance | 242.69 | 88 | 0.972 | 0.053 | 0.029 | 3 vs. 2 | 23.53 ** | 9 | 0.003 | <0.001 |

| Cohesion | ||||||||||

| 1. Configural invariance | 54.00 | 18 | 0.983 | 0.056 | 0.029 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 2. Metric invariance | 57.28 | 23 | 0.983 | 0.049 | 0.035 | 2 vs. 1 | 2.20 (ns) | 5 | <0.001 | 0.007 |

| 3. Scalar invariance | 70.77 | 28 | 0.979 | 0.049 | 0.039 | 3 vs. 2 | 13.91 * | 5 | 0.004 | <0.001 |

| χ2(df) | AIC | BIC | RMSEA | CFI | RMR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SEMs | ||||||

| 1 PAS–CLOS–CONF–COH | 2604.39 (1316) | 88,133.14 | 89,198.56 | 0.033 | 0.933 | 0.063 |

| 2 EIS–CLOS–CONF–COH | 2608.13 (1316) | 89,103.39 | 90,168.80 | 0.033 | 0.931 | 0.062 |

| 3 PASC–CLOS–CONF–COH | 2495.38 (1316) | 88,299.21 | 89,364.62 | 0.032 | 0.937 | 0.061 |

| 4 WIS–CLOS–CONF–COH | 2525.31 (1316) | 91,050.30 | 92,115.72 | 0.032 | 0.936 | 0.061 |

| 5 PCS–CLOS–CONF–COH | 2734.63 (1422) | 94,712.68 | 95,811.54 | 0.032 | 0.934 | 0.062 |

| 6 SPS–CLOS–CONF–COH | 2536.55 (1316) | 88,135.21 | 89,200.62 | 0.033 | 0.934 | 0.062 |

| 7 CLOS–CONF–COH | 2156.91 (1035) | 5586.05 | 76,480.66 | 0.036 | 0.934 | 0.066 |

| Estimate | SE | CR | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Models | |||

| Autoregressive effects | |||

| PAS t1 → PAS t2 | 0.57 *** | 0.06 | 10.23 |

| EIS t1 → EIS t2 | 0.54 *** | 0.07 | 7.67 |

| PASC t1 → PASC t2 | 0.60 *** | 0.05 | 11.87 |

| Cross-lagged effects | |||

| PAS t1 → CLOS t2 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 1.21 |

| PAS t1 → CONF t2 | −0.06 | 0.05 | −1.33 |

| PAS t1 → COH t2 | 0.11 | 0.06 | 1.75 |

| CLOS t1 → PAS t2 | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.08 |

| CONF t1 → PAS t2 | −0.08 | 0.05 | −1.45 |

| COH t1 → PAS t2 | 0.10 | 0.06 | 1.75 |

| EIS t1 → CLOS t2 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 1.39 |

| EIS t1 → CONF t2 | −0.02 | 0.06 | −0.35 |

| EIS t1 → COH t2 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 1.45 |

| CLOS t1 → EIS t2 | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.59 |

| CONF t1 → EIS t2 | −0.10 | 0.06 | −1.80 |

| COH t1 → EIS t2 | −0.01 | 0.06 | −0.12 |

| PASC t1 → CLOS t2 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.28 |

| PASC t1 → CONF t2 | −0.11 * | 0.05 | −2.37 |

| PASC t1 → COH t2 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 1.11 |

| CLOS t1 → PASC t2 | −0.05 | 0.06 | −0.95 |

| CONF t1 → PASC t2 | −0.08 | 0.05 | −1.70 |

| COH t1 → PASC t2 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 1.46 |

| Estimate | SE | CR | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Models | |||

| Autoregressive effects | |||

| WIS t1 → WIS t2 | 0.55 *** | 0.04 | 12.44 |

| PCS t1 → PCS t2 | 0.63 *** | 0.04 | 14.45 |

| SPS t1 → SPS t2 | 0.41 *** | 0.07 | 6.16 |

| Cross-lagged effects | |||

| WIS t1 → CLOS t2 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 1.44 |

| WIS t1 → CONF t2 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.83 |

| WIS t1 → COH t2 | −0.05 | 0.05 | −0.93 |

| CLOS t1 → WIS t2 | −0.07 | 0.05 | −1.29 |

| CONF t1 → WIS t2 | 0.05 | 0.05 | 1.00 |

| COH t1 → WIS t2 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 1.63 |

| PCS t1 → CLOS t2 | −0.01 | 0.05 | −0.09 |

| PCS t1 → CONF t2 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.35 |

| PCS t1 → COH t2 | −0.09 | 0.05 | −1.68 |

| CLOS t1 → PCS t2 | −0.02 | 0.05 | −0.53 |

| CONF t1 → PCS t2 | 0.11 * | 0.05 | 2.15 |

| COH t1 → PCS t2 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 1.87 |

| SPS t1 → CLOS t2 | −0.01 | 0.06 | −0.23 |

| SPS t1 → CONF t2 | −0.03 | 0.05 | −0.51 |

| SPS t1 → COH t2 | 0.09 | 0.07 | −1.22 |

| CLOS t1 → SPS t2 | −0.01 | 0.05 | −0.28 |

| CONF t1 → SPS t2 | 0.21 *** | 0.06 | 3.90 |

| COH t1 → SPS t2 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 1.39 |

| Estimate | SE | CR | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model | |||

| Autoregressive effects | |||

| CLOS t1 → CLOS t2 | 0.49 *** | 0.05 | 9.85 |

| CONF t1 → CONF t2 | 0.54 *** | 0.05 | 10.57 |

| COH t1 → COH t2 | 0.47 *** | 0.06 | 8.06 |

| Cross-lagged effects | |||

| CLOS t1 → CONF t2 | −0.07 | 0.05 | −1.28 |

| CLOS t1 → COH t2 | −0.02 | 0.06 | −0.43 |

| CONF t1 → CLOS t2 | −0.07 | 0.05 | −1.37 |

| CONF t1 → COH t2 | −0.10 | 0.06 | −1.73 |

| COH t1 → CLOS t2 | 0.09 | 0.06 | 1.69 |

| COH t1 → CONF t2 | −0.08 | 0.05 | −1.54 |

| Estimate | SE | CR | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Positive academic self-concept (StudWB) t1 → Conflict (TSR) t1 | −0.11 * | 0.05 | −2.37 |

| 2. Conflict (TSR) t1→ Physical complaints (StudWB) t2 | 0.11 * | 0.05 | 2.15 |

| 3. Conflict (TSR) t1→ Social problems in school (StudWB) t2 | 0.21 *** | 0.06 | 3.90 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Saxer, K.; Schnell, J.; Mori, J.; Hascher, T. The Relationship Between Student Well-Being and Teacher–Student and Student–Student Relationships: A Longitudinal Approach Among Secondary School Students in Switzerland. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 384. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030384

Saxer K, Schnell J, Mori J, Hascher T. The Relationship Between Student Well-Being and Teacher–Student and Student–Student Relationships: A Longitudinal Approach Among Secondary School Students in Switzerland. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(3):384. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030384

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaxer, Katja, Jakob Schnell, Julia Mori, and Tina Hascher. 2025. "The Relationship Between Student Well-Being and Teacher–Student and Student–Student Relationships: A Longitudinal Approach Among Secondary School Students in Switzerland" Education Sciences 15, no. 3: 384. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030384

APA StyleSaxer, K., Schnell, J., Mori, J., & Hascher, T. (2025). The Relationship Between Student Well-Being and Teacher–Student and Student–Student Relationships: A Longitudinal Approach Among Secondary School Students in Switzerland. Education Sciences, 15(3), 384. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030384