Co-Adapting a Reflective Video-Based Professional Development in Informal STEM Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

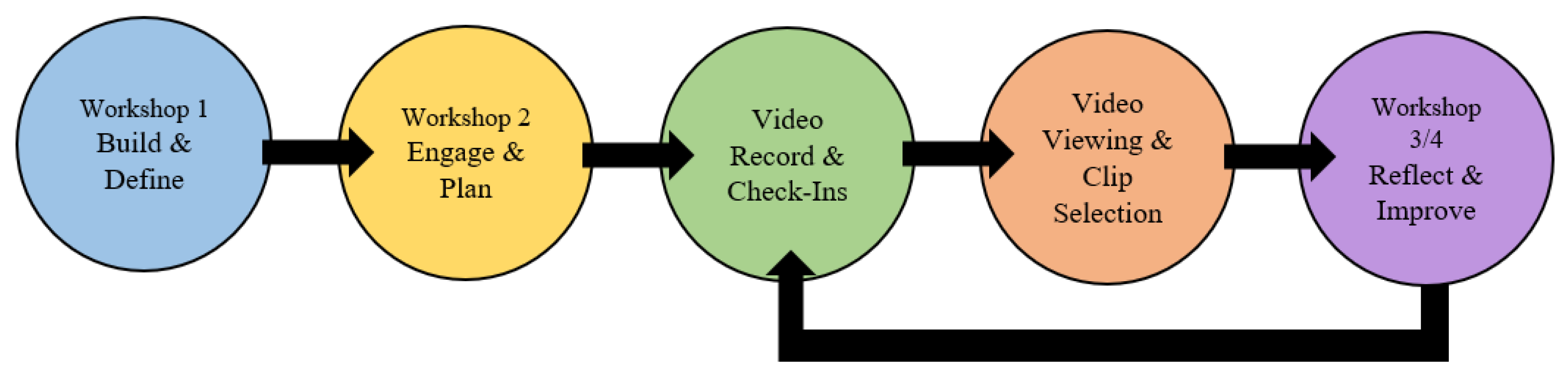

2. Overview of Professional Development Cycle

3. Materials and Methods

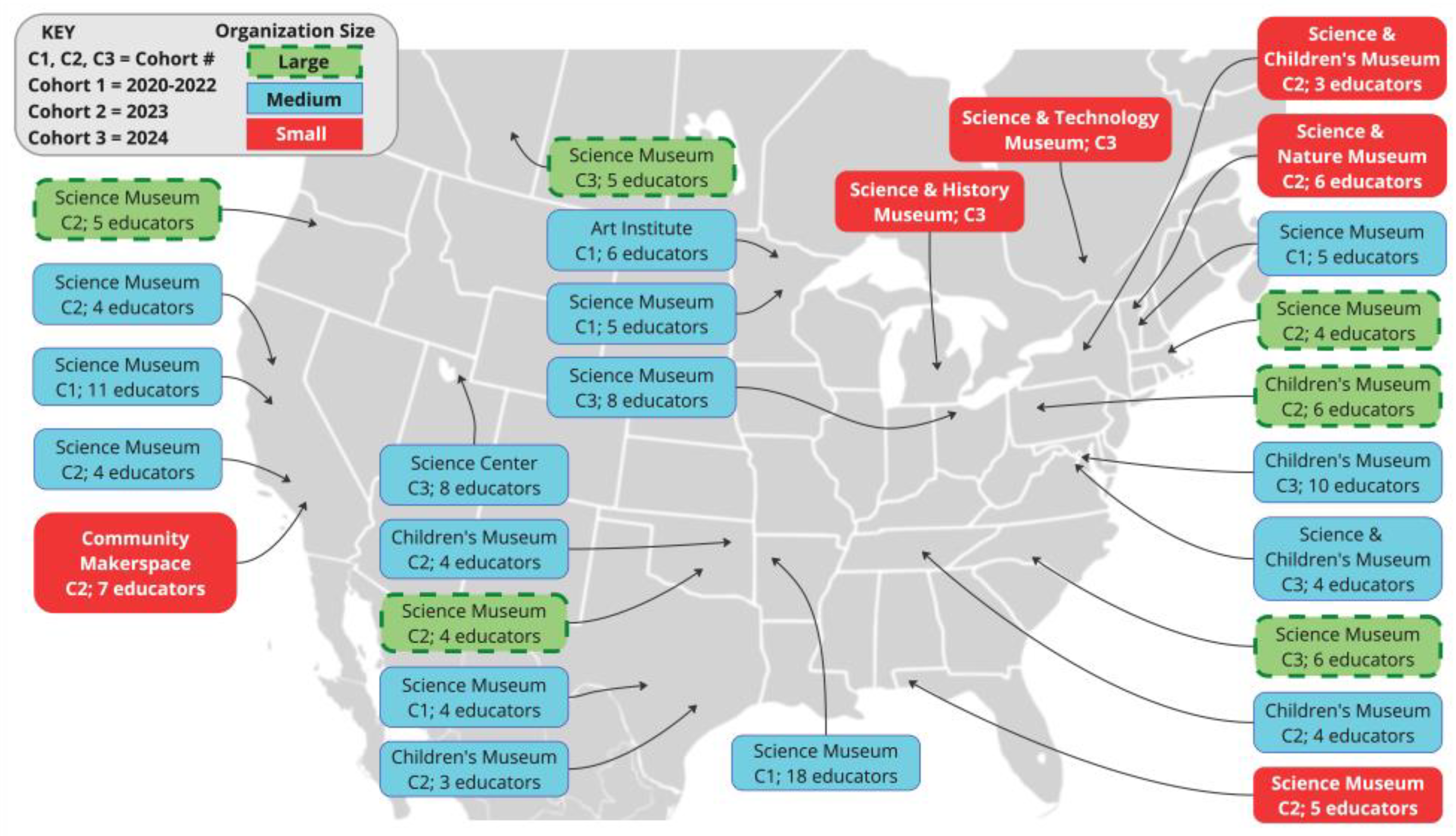

3.1. Organization and Participant Information

3.2. Data Source

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results

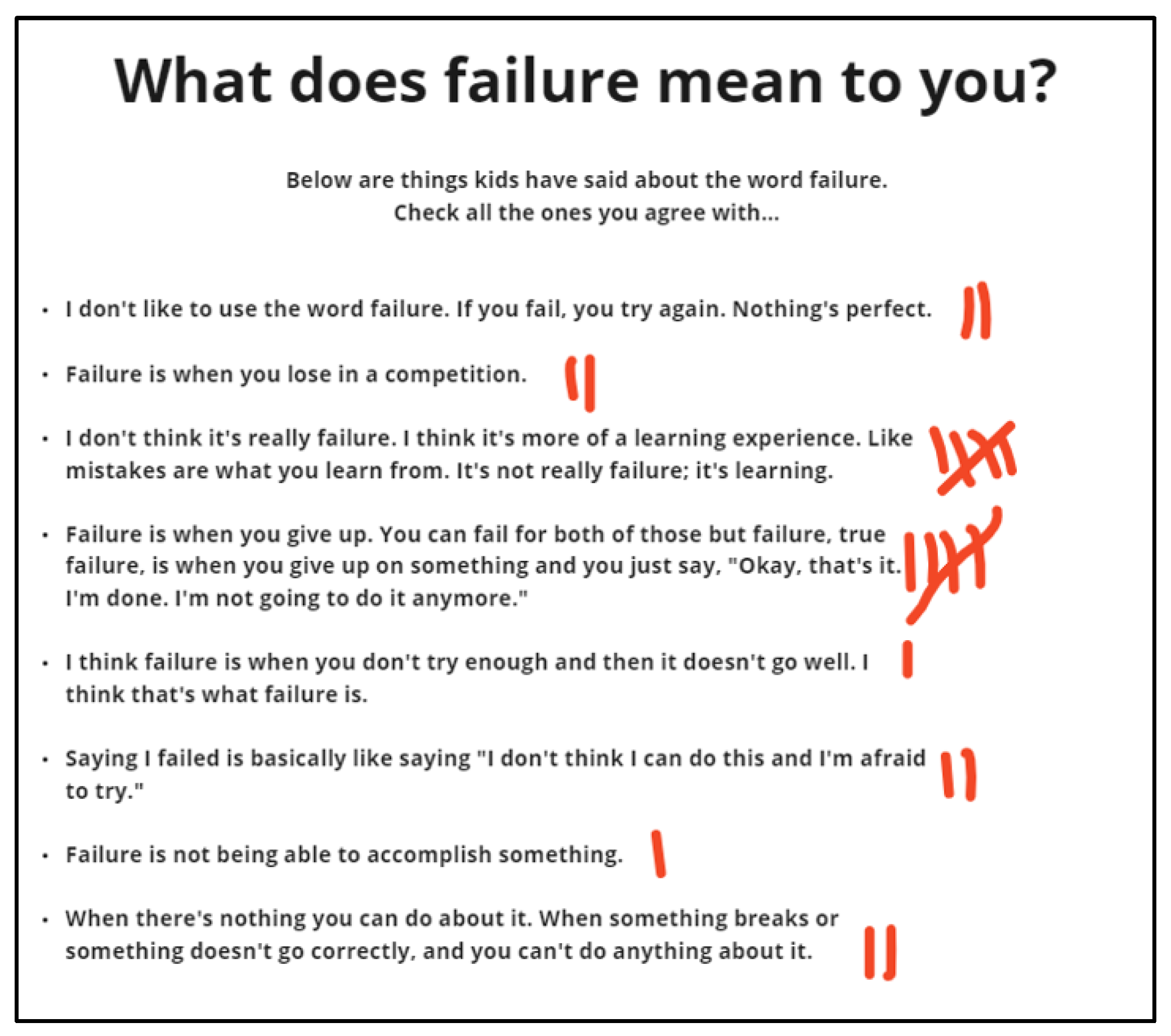

4.1. Educators’ Discomfort and Vulnerabilities

We also made sure Aurora and I [lead facilitators] were also being filmed so that it wasn’t just us critiquing other people that they were also turning around and critiquing videos of us. And we were filming ourselves so that we could get in the mindset of nobody’s perfect. Everybody has room for improvement. And everybody has failure moments. So I think just the trust that was built, knowing that this was like an all around experience, for everyone. We were all sitting in the same seat … and thinking about it as a universal educator kind of moment, you know, this is hard to watch.(Cohort 1, 27 October 2021)

4.2. Time Constraints

We did not want to add to their [educators] workload in terms of watching their own clips. But we did not ask if they wanted to do this because we knew they would want to watch their clips, which would add to their workload and anxiety.(4 October 2023)

4.3. Staff Turnover

4.4. Lack of Tools

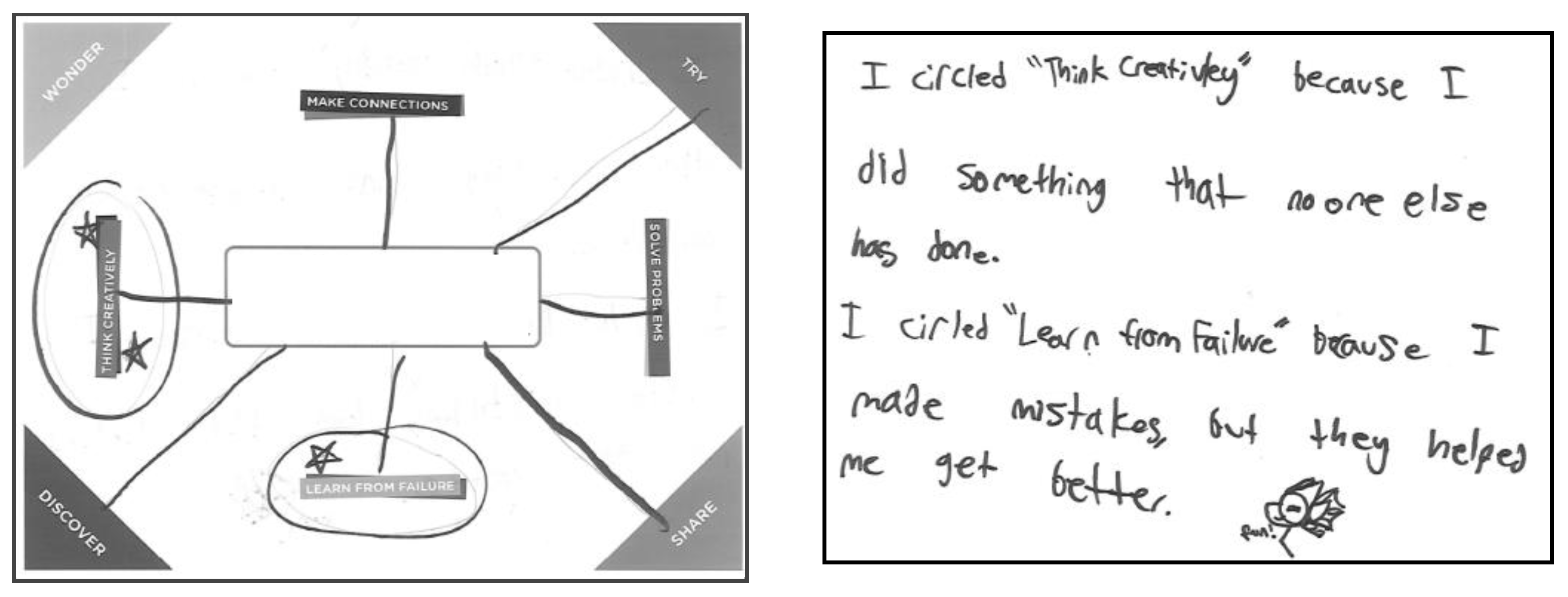

5. Discussion

Such actions were grounded in the reflective video-based professional development, which strengthens the notion of reflection as an approach to transform educational practices, organizational structures, and self-understanding as educators (Mohamed et al., 2022; Tran, 2021).In our organization as a whole, we have continued to look into other ways to encourage a growth mindset and acceptance of failure as a part of the workplace. We are interested to see how the industry at large addresses failure and find ways within our organization to improve our processes by embracing failure, taking risks, and trying new things. This mindset has allowed us to have more vocabulary and tools to accomplish organizational goals.(6 November 2024)

Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | While our focus was on educator–youth interactions through failure moments, there were instances in which educators interacted with adults or family groups. |

References

- Allen, L. B., & Crowley, K. (2017). From acquisition to inquiry: Supporting informal educators through iterative implementation of practice. In P. G. Patrick (Ed.), Preparing Informal Science Education (pp. 87–104). Springer International. [Google Scholar]

- Amador, J. M., Wallin, A., Keehr, J., & Chilton, C. (2023). Collective noticing: Teachers’ experiences and reflection on a mathematics video club. Mathematics Education Research Journal, 35, 557–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, L., Godec, S., Patel, U., Dawson, E., & Calabrese Barton, A. (2024). ‘It really has made me think’: Exploring how informal STEM learning practitioners developed critical reflective practice for social justice using the Equity Compass tool. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 32(5), 1243–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beisiegel, M., Mitchell, R., & Hill, H. C. (2018). The design of video-based professional development: An exploratory experiment intended to identify effective features. Journal of Teacher Education, 69(1), 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergen, N., & Labonté, R. (2020). “Everything is perfect, and we have no problems”: Detecting and limiting social desirability bias in qualitative research. Qualitative Health Research, 30(5), 783–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevan, B., & Xanthoudaki, M. (2008). Professional development for museum educators: Unpinning the underpinnings. Journal of Museum Education, 33(2), 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borko, H., Jacobs, J., Koellner, K., & Swackhamer, L. E. (2015). Mathematics professional development: Improving teaching using the problem-solving cycle and leadership preparation models. Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 328–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, S., Greenwood, M., Prior, S., Shearer, T., Walkem, K., Young, S., Bywaters, D., & Walker, K. (2020). Purposive sampling: Complex or simple? Research case examples. Journal of Research in Nursing, 25(8), 652–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G., Chan, C. K., Chan, K. K., Clarke, S. N., & Resnick, L. B. (2020). Efficacy of video-based teacher professional development for increasing classroom discourse and student learning. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 29(4–5), 642–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarà, M. (2015). What is reflection? Looking for clarity in an ambiguous notion. Journal of Teacher Education, 66(3), 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N. (1984). The research act. Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Desimone, L. M. (2009). Improving impact studies of teachers’ professional development: Toward better conceptualizations and measures. Educational Researcher, 38(3), 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunst, C. J., Bruder, M. B., & Hamby, D. W. (2015). Metasynthesis of in-service professional development research: Features associated with positive educator and student outcomes. Educational Research and Reviews, 10(12), 1731–1744. [Google Scholar]

- Frehill, L. M., & Pelczar, M. (2018). Data file documentation: Museum data files, FY 2018 release. Institute of Museum and Library Services. [Google Scholar]

- Fusch, P., Fusch, G. E., & Ness, L. R. (2018). Denzin’s paradigm shift: Revisiting triangulation in qualitative research. Journal of Sustainable Social Change, 10(1), 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garet, M. S., Porter, A. C., Desimone, L., Birman, B. F., & Yoon, K. S. (2001). What makes professional development effective? Results from a national sample of teachers. American Educational Research Journal, 38(4), 915–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabman, R., Stol, T., McNamara, A., & Brahms, L. (2019). Creating and sustaining a culture of reflective practice: Professional development by and for museum-based maker educators. Journal of Museum Education, 44(2), 155–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grenier, R. S. (2009). The role of learning in the development of expertise in museum docents. Adult Education Quarterly, 59(2), 142–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollingsworth, H., & Clarke, D. (2017). Video as a tool for focusing teacher self-reflection: Supporting and provoking teacher learning. Journal of Mathematics Teacher Education, 20(5), 457–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lottero-Perdue, P. S., & Parry, E. A. (2017). Perspectives on failure in the classroom by elementary teachers new to teaching engineering. Journal of Pre-College Engineering Education Research, 7(1), 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loucks-Horsley, S., Stiles, K. E., Mundry, S., Love, N., & Hewson, P. W. (2009). Designing professional development for teachers of science and mathematics. Corwin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marks, J., & Chase, C. C. (2019). Impact of a prototyping intervention on middle school students’ iterative practices and reactions to failure. Journal of Engineering Education, 108(4), 547–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L. W. (2021). Can reflective practice be sustained in museums? In L. U. Tran, & C. Halversen (Eds.), Reflecting on practice for STEM educators: A guide for museums, out-of-school, and other informal settings (pp. 40–50). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, M., Rashid, R. A., & Alqaryouti, M. H. (2022). Conceptualizing the complexity of reflective practice in education. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1008234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, S., Roche, J., Bell, L., & Neenan, E. E. (2020). Supporting facilitators of maker activities through reflective practice. Journal of Museum Education, 45(1), 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulhall, A. (2003). In the field: Notes on observation in qualitative research. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 41(3), 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Museums Moving Forward. (2022). Workplace equity and organizational culture in US art museums. Available online: https://museumsmovingforward.com/data-studies/2022-2023/foreword (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Nawab, A., Bissaker, K., & Datoo, A. K. (2021). Contemporary trends in professional development of teachers: Importance of recognising the context. International Journal of Educational Management, 35(6), 1176–1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, C. (2019). Thoughts on the history of professional development programs in museums. Journal of Museum Education, 44(2), 123–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancar, R., Atal, D., & Deryakulu, D. (2021). A new framework for teachers’ professional development. Teaching and Teacher Education, 101, 103305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schön, D. (1983). The reflective practitioner: How professionals think in action. Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Seidel, T., Stürmer, K., Blomberg, G., Kobarg, M., & Schwindt, K. (2011). Teacher learning from analysis of videotaped classroom situations: Does it make a difference whether teachers observe their own teaching or that of others? Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(2), 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherin, M. G. (2004). New perspectives on the role of video in teacher education. In J. Brophy (Ed.), Advances in research on teaching: Using video in teacher education (pp. 1–27). Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, A., Anderson, A., Goeke, M., Caruana, D., & Maltese, A. V. (2025). Identifying and shifting educators’ failure pedagogical mindsets through reflective practices. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 95(1), 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, A., Anderson, A., & Maltese, A. V. (2019). Caught on camera: Youth and educators’ noticing of and responding to failure within making contexts. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 28(5), 480–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, A., Anderson, A., Maltese, A. V., & Goeke, M. (2018). "I’m going to fail": How youth interpret failure across contextual boundaries. In J. Kay, & R. Luckin (Eds.), Proceedings of the 13th International Conference of the Learning Science (Vol. 2, pp. 981–984). University College London. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, A., & Maltese, A. V. (2017). “Failure is a major component of learning anything”: The role of failure in the career development of STEM professionals. Journal of Science and Technology Education, 26(2), 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simpson, A., Maltese, A. V., Paul, K., & Penney, L. (2024, June 23–26). Failure in focus: Unpacking the impact of video-based reflections on museum educator practices. Proceedings of the 131th meeting of the American Society for Engineering Education, Portland, OR, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, A., Osterhout, A., Anderson, A., & Maltese, A. V. (2024). Museum educators’ perspective of failure: A collective frame analysis. Curator: The Museum Journal. [Advanced online publication]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavory, I. (2020). Interviews and inference: Making sense of interview data in qualitative research. Qualitative Sociology, 43(4), 449–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, E. W., Neill, A. C., & Banz, R. (2008). Teaching in situ: Nonformal museum education. Canadian Journal for the Study of Adult Education, 21(1), 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, L. U. (2021). The how and why of reflective practice. In L. U. Tran, & C. Halversen (Eds.), Reflecting on practice for STEM educators: A guide for museums, out-of-school, and other informal settings (pp. 7–22). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, L. U., Gupta, P., & Bader, D. (2019). Redefining professional learning for museum education. Journal of Museum Education, 44(2), 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, L. U., & Halversen, C. (2021). Reflecting on practice for STEM educators: A guide for museums, out-of-school, and other informal settings. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, L. U., Werner-Avidon, M., & Newton, L. R. (2013). Successful professional learning for informal educators: What is it and how do we get there? Journal of Museum Education, 38(3), 333–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wager, A., Caldwell, B., & Vescio, J. (2023). A teacher’s guide to video club and other tip for professional development. Mathematics Teacher Educator, 12(2), 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, A. M., Akiva, T., Wardrip, P. S., & Brahms, L. (2021). Facilitated making in museum-based educational makerspaces. Curator: The Museum Journal, 64(1), 131–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarrinabadi, N., & Afsharmehr, E. (2022). Teachers’ mindsets about L2 learning: Exploring the influences on pedagogical practices. RELC Journal, 55(1), 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year, Cohort | Number of Organizations | Data Source and Total Time | Overarching Objective |

|---|---|---|---|

| Year 1, Cohort 1 | 6 | 16 group meetings 18 h 30 min | Co-adapt the original PD cycle grounded in math education. |

| Year 2, Cohort 1 | 5 | 8 group meetings 10 h 26 min | Implement and co-refine the working PD cycle from Year 1. |

| Year 3, Cohort 2 | 13 (Group of 7 and Group of 6) | 8 group meetings each 14 h 47 min | Implement and co-refine the working PD cycle from Year 2. |

| Year 4, Cohort 3 | 8 | 3–4 individual meetings per organization ~13 h | Implement the PD cycle from Year 2 using the project website. Support changes to the website. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Simpson, A.; Anderson, A.; Maltese, A.V.; Penney, L.; Paul, K. Co-Adapting a Reflective Video-Based Professional Development in Informal STEM Education. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030353

Simpson A, Anderson A, Maltese AV, Penney L, Paul K. Co-Adapting a Reflective Video-Based Professional Development in Informal STEM Education. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(3):353. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030353

Chicago/Turabian StyleSimpson, Amber, Alice Anderson, Adam V. Maltese, Lauren Penney, and Kelli Paul. 2025. "Co-Adapting a Reflective Video-Based Professional Development in Informal STEM Education" Education Sciences 15, no. 3: 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030353

APA StyleSimpson, A., Anderson, A., Maltese, A. V., Penney, L., & Paul, K. (2025). Co-Adapting a Reflective Video-Based Professional Development in Informal STEM Education. Education Sciences, 15(3), 353. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030353