Educational Interventions Through Physical Activity for Addiction Prevention in Adolescent Students—A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Source of Information and Search Strategies

2.3. Study Selection and Data Extraction Process

2.4. Quality Assessment

3. Results

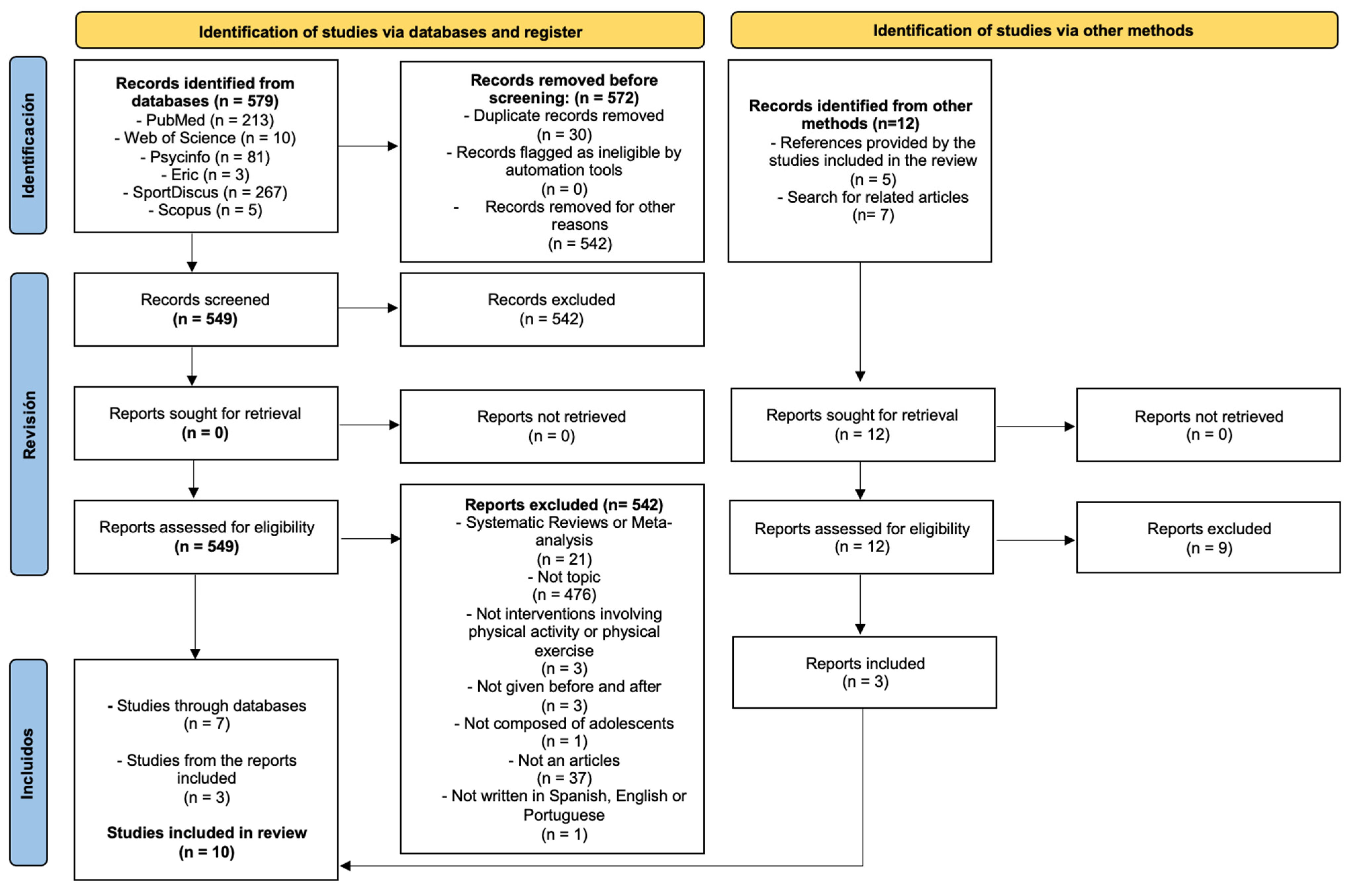

3.1. Selection of Studies

3.2. Quality of Studies

3.3. Characteristics of the Studies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Practical Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aaron, D. J., Dearwater, S. R., Anderson, R., Olsen, T., Kriska, A. M., & Laporte, R. E. (1995). Physical activity and the initiation of highrisk health behaviors in adolescents. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 27(12), 1639–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arteaga-Zambrano, V. M., & Mendoza-Alcívar, W. R. (2022). El Consumo de Sustancias Psicoactivas en Adolescentes de San Alejo durante la Pandemia por COVID-19. Polo del Conocimiento. Revista Científico-Profesional, 7(3), 1360–1381. [Google Scholar]

- Beete, L. (1994). About steroids. Channing. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, S., Witkiewitz, K., Dillworth, T. M., Chawla, N., Simpson, T. L., Ostafin, B. D., Larimer, M. E., Blume, A. W., Parks, G. A., & Marlatt, A. (2006). Mindfulness meditation and substance use in an incarcerated population. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 20(3), 343–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brellenthin, A. G., & Lee, D.-C. (2018). Physical activity and the development of substance use disorders: Current knowledge and future directions. Progress in Preventive Medicine, 3(3), e0018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brener, N. D., Collins, J. L., Kann, L., Warren, C. W., & Williams, B. I. (1995). Reliability of the Youth Risk Behavior Survey Questionnaire. American Journal of Epidemiology, 141(6), 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brook, J., Rifenbark, G. G., Boulton, A., Little, T. D., & McDonald, T. P. (2015). Risk and protective factors for drug use among youth living in foster care. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 32(2), 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butzer, B., LoRusso, A., Shin, S. H., & Khalsa, S. B. S. (2017). Evaluation of yoga for preventing adolescent substance use risk factors in a middle school setting: A preliminary group-randomized controlled trial. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46, 603–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccarini, J., Hompes, T., Verhaeghen, A., Casteels, C., Peuskens, H., Bormans, G., Claes, S., & Laere, K. V. (2014). Changes in cerebral CB1 receptor availability after acute and chronic alcohol abuse and monitored abstinence. The Journal of Neuroscience, 34(8), 2822–2831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24, 385–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collingwood, T. R., Reynolds, R., Kohl, H. W., Smith, W., & Sloan, S. (1991). Physical fitness effects on substance abuse risk factors and use patterns. Journal of Drug Education, 21(1), 73–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collingwood, T. R., Sunderlin, J., Reynolds, R., & Kohl, H. W. (2000). Physical training as a substance abuse prevention intervention for youth. Journal of Drug Education, 30(4), 435–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper Institute for Aerobics Research. (1987). Fitnessgram test administration manual. Institute for Aerobics Research. [Google Scholar]

- Craft, L. L., & Perna, F. M. (2004). The benefits of exercise for the clinically depressed. The Primary Care Companion to the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 6(3), 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dever, B. V., Schulenberg, J. E., Dworkin, J. B., O’Malley, P. M., Kloska, D. D., & Bachman, J. G. (2012). Predicting risk-taking with and without substance use: The effects of parental monitoring, school bonding and sports participation. Prevention Science, 13, 605–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espada, J. P., Gonzálvez, M. T., Guillén-Riquelme, A., Sun, P., & Sussman, S. (2014). Immediate effects of Project-EX in Spain: A classroom-based smoking prevention and cessation intervention program. Journal of Drug Education: Substance Abuse Research and Prevention, 44(1–2), 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fagan, M. J., Glowacki, K., & Faulkner, G. (2021). “You get that craving and you go for a half-hour run”: Exploring the acceptability of exercise as an adjunct treatment for substance use disorder. Mental Health and Physical Activity, 21, 100424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazio, A. F. (1977). A concurrent validation study of the NCHS general well being scale vital and health statistics. National Center for Health Statistics. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, D., Miller, S., Herman-Stahl, M., Williams, J., Lavery, B., Markovitz, L., Kluckman, M., Mosoriak, G., & Johnson, M. (2015). Behavioral and psychophysiological effects of a yoga intervention on high-risk adolescents: A randomized control trial. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25, 518–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgakouli, K., Manthou, E., Georgoulias, P., Ziaka, A., Fatouros, I. G., Mastorakus, G., Koutedakis, Y., Theodorakis, Y., & Jamurtas, A. Z. (2017). Exercise training reduces alcohol consumption but does not affect HPA-axis activity in heavy drinkers. Physiology and Behavior, 179, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godínez, J. A., & Gómez, G. B. (2012). Family, school and sports (FEDE), three areas in the lives of students in the state of Jalisco, Mexico: Analysis of the use of leisure time and the use or abuse of drugs. Salud y Drogas, 12(2), 193–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Goldberg, L., MacKinnon, D. P., Elliot, D. L., Moe, E. L., Clarke, G., & Cheong, J. W. (2000). The adolescents training and learning to avoid steroids program. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, 154(4), 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gür, F., & Can, G. (2020). Is exercise a useful intervention in the treatment of alcohol use disorder? Systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Health Promotion, 34(5), 520–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, R. W., & Tevis, B. W. (1977). A comparison of attitudes and behavior of high school athletes and non-athletes with respect to alcohol use and abuse. Journal of Alcohol and Drug Education, 23(1), 20–28. [Google Scholar]

- Horrell, J., Thompson, T. P., Taylor, A. H., Neale, J., Husk, K., Wanner, A., Creanor, S., Wei, Y., Kandiyali, R., Sinclair, J., Nasser, M., & Wallace, G. (2020). Qualitative systematic review of the acceptability, feasibility, barriers, facilitators and perceived utility of using physical activity in the reduction of and abstinence from alcohol and other drug use. Mental Health and Physical Activity, 19, 100355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hovhannisyan, K., Rasmussen, M., Adami, J., Wikström, M., & Tonnesen, H. (2020). Evaluation of very integrated program: Health promotion for patients with alcohol and drug addiction: A randomized trial. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 44(7), 1456–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kingsland, M., Wiggers, J. H., Vashum, K., Hodder, R. K., & Wolfenden, L. (2016). Interventions in sports settings to reduce risky alcohol consumption and alcohol-related harm: A systematic review. Systematic Reviews, 5, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kmet, L. M., Cook, L. S., & Lee, R. C. (2004). Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields. Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koo, T. K., & Li, M. Y. (2016). A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. Journal of Chiropratic Medicine, 15(2), 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuypers, K. P. C., Theunissen, E. L., Van Wel, J. H. P., De Sousa, E. B., Linssen, A., Sambeth, A., Schultz, B. G., & Ramaekers, J. G. (2016). Verbal memory impairment in polydrug ecstasy users: A clinical perspective. PLoS ONE, 11(2), e0149438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, D. C., & DeCamp, W. (2017). Sports will keep’em out of trouble: A comparative analysis of substance use among adolescents and young adults. Journal of Sport and Health Research, 9(1), 41–52. [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, H., & Wiers, R. W. (2016). Risk factors for adolescent drinking: An introduction. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 40(4), 653–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K. T. H., & Lowe, D. (2015). Out-of-school time and adolescent substance use. Journal of Adolescent Health, 57(5), 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, M. A., Litt, D. M., Fairlie, A. M., Kilmer, J. R., Kannard, E., Resendiz, R., & Walker, T. (2022). Investigating why and how young adults use protective behavioral strategies for alcohol and marijuana use: Protocol for developing a randomized controlled trial. JMIR Research Protocols, 11(4), e37106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieberman, D. Z. (2000). Children of alcoholic: An update. Current Opinion in Pediatrics, 12(4), 336–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lynam, D. R., Smith, G. T., Whiteside, S. P., & Cyders, M. A. (2006). The UPPS-P: Assessing five personality pathways to impulsive behavior. Purdue University. [Google Scholar]

- Mathews, A. E., Werch, C., Michniewicz, M., & Bian, H. (2007). An impact evaluation of two versions of a brief intervention targeting alcohol use and physical activity among adolescents. Journal of Drug Education, 37(4), 401–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melnyk, B. M., Jacobson, D., Kelly, S., Belyea, M., Shaibi, G., Small, L., O’Haver, J., & Marsiglia, F. F. (2013). Promoting healthy lifestyles in high school adolescents: A randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 45(4), 407–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mewton, L., Visontay, R., Chapman, C., Mewton, N., Slade, T., Kay-Lambkin, F., & Teesson, M. (2018). Universal prevention of alcohol and drug use: An overview of reviews in an Australian context. Drug and Alcohol Review, 37(1), 435–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, S., Herman-Stahl, M., Fishbein, D., Lavery, B., Johnson, M., & Markovits, L. (2014). Use of formative research to develop a yoga curriculum for high-risk youth: Implementation considerations. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion, 7(3), 171–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modric, T., Zenic, N., & Sekulic, D. (2011). Substance use and misuse among 17 to 18 year-old croatian adolescents: Correlation with scholastic variables and sport factors. Substance Use and Misuse, 46(10), 1328–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., Shekelles, P., Stewart, L. A., & PRISMA Group. (2015). Preferred reporting ítems for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews, 4(1), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, M. J., & Werch, C. (2007). Results of a two-year longitudinal study of beverage-specific alcohol use among adolescents. Journal of Drug Education, 37(2), 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niedermeier, M., Frühauf, A., Koop-Wilfling, P., Rumpold, G., & Koop, M. (2018). Alcohol consumption and physical activity in austrian college students: A cross-sectional study. Substance Use and Misuse, 53(10), 1581–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, C. P., Gastfriend, D. R., Forman, R. F., Schweizer, E., & Pettinati, H. M. (2011). Long-term opioid blockade and hedonic response: Preliminary data from two open-label extension studies with extended-release naltrexone. American of Journal Psychiatry, 20(2), 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odgers, C. L., Caspi, A., Nagin, D. S., Piquero, A. R., Slutske, W. S., Milne, B. J., Dickson, N., Poulton, R., & Moffitt, T. E. (2008). Is it important to prevent early exposure to drugs and alcohol among adolescents? Psychological Science, 19(10), 1037–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oscar-Berman, M., Valmas, M., Sawyer, K., Ruiz, S., Luhar, R., & Gravitz, Z. R. (2014). Profiles of impaired, spared and recovered neuropsychologic processes in alcoholism. Handbook of Clinical Neurology, 125, 183–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … McGuinness, L. A. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. International Journal of Surgery, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parfilova, G. G., & Velieva, S. V. (2016). Preventive work with teenagers who are prone to addiction, in terms of educational space. International Journal of Environmental and Science Education, 11(8), 1901–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peirs, E., & Harris, D. (1969). Children’s self concept scale. Counselor Recordings and Tests. [Google Scholar]

- Schijven, E. P., Hulsmans, D. H. G., Van Der Nagel, J. E. L., Lammers, J., Otten, R., & Poelen, E. A. P. (2020). The effectiveness of an indicated prevention programme for substance use in individuals with mild intellectual disabilities and borderline intellectual functioning: Results of a quasi-experimental study. Addiction, 116(2), 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekulic, D., Ostojic, M., Ostojic, Z., Hajdarevic, B., & Osotojic, L. (2012). Substance abuse prevalence and its relation to scholastic achievement and sport factors: An analysis among adolescents of the Herzegovina-Neretva Canton in Bosnia and Herzegovina. BMC Public Health, 12(274), 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidhu, A. K., Sussman, S., Tewari, A., Bassi, S., & Arora, M. (2016). Project-EX-India: A classroom-based tobacco use prevention and cessation intervention program. Addictive Behaviors, 53, 53–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P., Miyano, J., Ann, L., Dent, C., & Sussman, S. (2007). Short-term effects of Project-EX-4: A classroom-based smoking prevention and cessation intervention program. Addictive Behaviors, 32(2), 342–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sussman, S., Dent, C. W., & Lichtman, K. L. (2001). Project-EX: Outcomes of a teen smoking cessation program. Addictive Behaviors, 26(3), 425–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, H., Swartz, M. D., Marsden, D., & Perry, C. L. (2021). The future of substance abuse now: Relationships among adolescent use of vaping devices, marijuana and synthetic cannabinoids. Substance Use and Misuse, 56(2), 192–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terry, P. C., Lane, A. M., & Fogarty, G. J. (2003). Construct validity of the Profile of Mood States-Adolescentes (POMS-A) for use with adults. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 4(2), 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, T. P., Horrell, J., Taylor, A. H., Wanner, A., Husk, K., Wei, Y., Creanor, S., Kandiyali, R., Neale, J., Sinclair, J., Nasser, M., & Wallace, G. (2020). Physical activity and the prevention, reduction and treatment of alcohol and other drug use across the lifespan (The PHASE review): A systematic review. Mental Health and Physical Activity, 19, 100360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Zwaluw, C., & Engels, R. C. M. E. (2009). Gene-environment interactions and alcohol use and dependence: Current status and future challenges. Addiction, 104(6), 907–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veliz, P. T., Boyd, C. J., & McCabe, S. E. (2015). Competitive sport involvement and substance use among adolescents: A nationwide study. Substance Use and Misuse, 50(2), 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, K. D., Weg, M. W., & Klesges, R. C. (2003). Characteristics of highly physically active smokers in a population of young adult military recruits. Addictive Behaviors, 28(8), 1405–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, R., & Gould, D. (1996). Fundamentos de psicología del deporte y el ejercicio físico. Ariel. [Google Scholar]

- Welford, P., Gunillasdotter, V., Andréasson, S., & Hallgren, M. (2022). Effects of physical activity on symptoms of depression and anxiety in adults with alcohol use disorder (FitForChange): Secondary outcomes of a randomised controlled trial. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 239, 109601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werch, C., Moore, M. J., DiClemente, C. C., Bledose, R., & Jobli, E. (2005). A multihealth behavior intervention integrating physical activity and substance use prevention for adolescents. Prevention Science, 6(3), 213–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wichstrom, T., & Wichstrom, L. (2009). Does sports participation during adolescence prevent later alcohol, tobacco and cannabis use? Addiction, 104(1), 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wills, T. A., & Ainette, M. G. (2010). Temperament, self-control and adolescent substance use. In L. M. Scheier (Ed.), Handbook of drug use etiology: Theory, methods and empirical findings (pp. 127–146). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., & Yuan, T. F. (2019). Exercise and substance abuse. International Review of Neurobiology, 147, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., & Liu, X. (2022). A systematic review of exercise intervention program for people with substance use disorder. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 817927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zschucke, E., Heinz, A., & Ströhle, A. (2012). Exercise and physical activity in the therapy of substance use disorders. The Scientific World Journal, 2012, 901741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Studies | Observer 1 | Observer 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Schijven et al. (2020) | 0.78 | 0.78 |

| Butzer et al. (2017) | 0.92 | 0.82 |

| Sidhu et al. (2016) | 0.86 | 0.83 |

| Fishbein et al. (2015) | 0.84 | 0.75 |

| Espada et al. (2014) | 0.85 | 0.78 |

| Melnyk et al. (2013) | 0.92 | 0.78 |

| Sun et al. (2007) | 0.78 | 0.71 |

| Collingwood et al. (2000) | 0.65 | 0.65 |

| Goldberg et al. (2000) | 0.78 | 0.75 |

| Collingwood et al. (1991) | 0.70 | 0.65 |

| Studies /Authors | Country | Design | Duration of Study | N (Gender) N (CG y EG) | Age Subjects | Characteristics of the Participants | Variables |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schijven et al. (2020) | The Netherlands | Quasi-experimental, with pre-test and post-test measures (1 CG/1 EG). No long-term follow-up evaluations were executed. | 6 weeks, 5 group sessions of 45 min each; 5 individual sessions of 30 min each; a total of 10 sessions | 66 participants (19 girls) (47 girls) CG: 32 (12 girls; 20 boys) EG: 34 (7 girls; 27 girls) | NR M = 17.45 SD = 2.76 CG: (M = 17.72; SD = 2.88) EG: (M = 17.21; SD = 2.67) | Overall, 24% of the adolescents were frequent alcohol users, reporting weekly or daily alcohol consumption at baseline, 41% used cannabis weekly or daily, and 20% used illicit drugs weekly or daily. Furthermore, 23% of participants reported being daily or weekly poly-drug users of tobacco, cannabis, and/or other drugs at the start of the study. | “Risk profile in the use of tobacco, cannabis and/or other drugs” “Frequency of use of alcohol, cannabis and/or other drugs” “Binge drinking” “Severity of alcohol, cannabis and/or other drug use” |

| Butzer et al. (2017) | United States | Randomised controlled trial, with pre-test and post-test measures (1 CG/1 EG). Long-term follow-up evaluations (6 and 12 months). | 6 months 1–2 weekly sessions of 35 min each A total of 48 sessions | 209 participants (132 girls) (77 girls) CG: 93 (61 girls; 32 boys) EG: 116 (71 girls; 45 girls) | 12–13 years old M = 12.64 SD = 0.33 | ESO students (7th grade) considered high-performing, from a public school with a variety of ethnic and socio-economic backgrounds (mainly included those students with a lower-middle socio-economic level). Participants reported being users of tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, and/or other drugs at the start of the study. The demographics also suggest that the study sample was composed primarily of White and Asian students. | “Willingness and frequency to use tobacco, alcohol, cannabis and/or other drugs” “State of mind” “Stress” “Impulsivity” “Emotional self-regulation” “Quality of the programme” |

| Sidhu et al. (2016) | India | Quasi-experimental, with pre-test and post-test measures. Long-term follow-up assessment (3 months). | 6 weeks; 1–2 weekly sessions of 40–45 min each; a total of 8 sessions | 624 participants (262 girls) (362 girls) CG: 303 EG: 321 | 16–18 years old CG: (M = 16.15; SD = 0.61) EG: (M = 16.16; SD = 0.90) | ESO students from four different schools (two public and two private schools). Overall, 58% of the sample was male, 66% of the sample attended public schools, and only 16 or approximately 3% of participants reported being monthly tobacco smokers at the start of the study. | “Tobacco use” “Quality of the programme” |

| Fishbein et al. (2015) | United States | Randomised controlled trial, with pre-test and post-test measures (1 CG/1 EG). No long-term follow-up evaluations were executed. | 7 weeks 3 weekly sessions of 50 min each A total of 20 sessions | 85 participants (46 girls) (39 girls) CG: 40 EG: 45 | 14–20 years old M = 16.70 SD = NR | ESO students (9–12th grade) with a high risk of school absenteeism and dropout, belonging to a specific public school for students with academic, family, and/or personal problems. Participants reported being users of alcohol, cannabis, and/or other drugs at the start of the study, and many students entered the school behind by 1–2 years in course credits, due to absenteeism, academic issues, or personal/family problems. | “Use of alcohol, cannabis and/or other drugs” “Physical fitness” “Emotional behaviour” “Stress” “Benefits gained through mindfulness” “State of mind” “Behavioural conduct” “Physiological aspects” |

| Espada et al. (2014) | Spain | Randomised controlled trial, with pre-test and post-test measures (3 CGs/3 EGs). No long-term follow-up evaluations were executed. | 6 weeks 1–2 weekly sessions of 40–45 min each A total of 8 sessions | 1546 participants (711 girls) (835 girls) CG: 716 EG: 830 | 14–21 years old M = 15.26 SD = 1.20 | ESO students from six schools in the province of Alicante (Spain). Approximately 32% of the participants had smoked a cigarette sometime in their lives and in the last 30 days, and 7.1% had on the day of the pretest assessment. | “Tobacco use/intention to use” “Nicotine dependence” “Acquired knowledge about consequences of tobacco use” “Quality of the programme” |

| Melnyk et al. (2013) | United States | Randomised controlled trial, with pre-test and post-test measures (1 CG/1 EG) Long-term follow-up assessment (6 months). | 4 months 1 weekly session of 20 min each A total of 15 sessions | 779 participants (402 girls) (377 girls) CG: 421 (207 girls; 214 boys) EG: 358 (195 girls; 163 girls) | 14–16 years old M = 14.74 SD = 0.73 C.G.: (M = 14.74; SD = 0.70) EG: (M = 14.75; SD = 0.76) | ESO students from 11 schools in the southwestern United States (the choice of schools was designed to provide diversity across race/ethnicity) enrolled in health education courses. Participants reported being alcohol and/or cannabis users at the start of the study. | “Alcohol and/or cannabis use” “Healthy lifestyle” “Body Mass Index” “Mental health” “Academic performance” |

| Sun et al. (2007) | United States | Randomised controlled trial, with pre-test and post-test measures (6 CGs/6 EGs). No long-term follow-up evaluations were executed. | 6 weeks 1–2 weekly sessions of 40–45 min each A total of 8 sessions | 878 participants (352 girls) (526 girls) CG: 391 EG: 487 | 13–19 years old M = 16.50 SD = 1.00 | ESO students from 12 schools in Southern California (US USA). A total of 33% of participants reported being weekly tobacco smokers at the start of the study. Approximately 52% of the students reported that they may smoke in the next 12 months. | “Tobacco use/intention to use” “Acquired knowledge about consequences of tobacco use” “Programme quality”: |

| Collingwood et al. (2000) | United States | Quasi-experimental, with pre-test and post-test measures (0 CGs/6 EGs). No long-term follow-up evaluations were executed. | 3 months; 3 weekly sessions of 90 min each (secondary school) and 120–180 min each (community centre); a total of 36 sessions | 329 participants (142 girls) (187 girls) CG: 0 EG: 329 3 EGs—secondary school: 111 (48 girls; 63 boys) 3 EGs—community centre: 218 (94 girls; 124 girls) | NR M = 12.13 SD = NR 3 EG secondary school: (M = 12.80; SD = NR) 3 EG community centre: (M = 14.46; SD = NR) | Youngsters from three high schools and three community centres, located in environments at risk of exclusion, established in small rural and urban areas of the city of Illinois. Participants reported being users of tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, and/or other drugs at the start of the study. | “Physical fitness” “Level of physical activity” “Risk factors in the use of tobacco, alcohol, cannabis and/or other drugs” “Use of tobacco, alcohol, cannabis and/or other drugs” “Quality of the programme” |

| Goldberg et al. (2000) | United States | Randomised controlled trial, with pre-test and post-test measures (16 CGs/15 EGs). Long-term follow-up assessment (12 months). | 4 months 1–2 weekly sessions of 45 min each A total of 22 sessions | 2516 participants (0 girls) (2516 chicas) CG: 1371 EG: 1145 | 15–16 years old M = 15.45 SD = NR CG: (M = 15.42; SD = 1.20) EG: (M = 15.48; SD = 1.19) | High school students (9th and 10th grade) from 34 schools in the Portland metropolitan area (USA). Participants reported being users of anabolic steroids, alcohol, and/or other drugs at the beginning of the study. Subjects belonged to a professional football team at their high school. | “Intention to use anabolic steroids” “Healthy diet” “Knowledge acquired about consequences of the use of sports supplements, consumption of anabolic steroids, alcohol and/or other drugs” “Intention to use alcohol and/or other drugs (cannabis, amphetamines or narcotics)” |

| Collingwood et al. (1991) | United States | Quasi-experimental, with pre-test and post-test measures (0 CGs/3 EGs). No long-term follow-up evaluations were executed. | 9 weeks 2 weekly sessions of 90 min each A total of 18 sessions | 74 participants (28 girls) (46 girls) CG: 0 EG: 74 1st EG—secondary school: 54 2nd EG—community centre: 11 3rd EG—health centre (hospital): 9 | NR M = 16.80 SD = NR 1st EG—secondary school: M = 17.50 SD = NR 2nd EG—community centre: M = 15.10 SD = NR 3rd EG—health centre (hospital): M = 15.10 SD = NR | High-risk adolescents reported being tobacco, alcohol, and/or cannabis users at the start of the study, at risk of dropping out of school, and substance users from a high school, a community centre, or a hospital in the city of Dallas. | “Physical fitness” “Risk factors related to tobacco, alcohol and/or cannabis use” “Use of tobacco, alcohol and/or cannabis” |

| Studies /Authors | Aim of the Study | Intervention Programme | Main Results | Conclusions | Limitations | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control G. | Experimental G. | |||||

| Schijven et al. (2020) | Aim: to evaluate the short-term effectiveness of the alcohol, cannabis and/or other drug prevention programme “Take it personal!” for Dutch adolescents with mild intellectual disabilities, borderline intellectual functioning, and delinquent behavioural problems. | Regular care was carried out, based on prevention and intervention programmes (without any PA, PE, or sports) against substance use (tobacco, cannabis, and/or other drugs). | The “Take it personal!” programme was implemented, focusing on four personality traits: (1) sensation seeking; (2) impulsive behaviour; (3) sensitivity to anxiety; and (4) negative thinking. Each session was adjusted to the cognitive abilities of the participants. | A stronger decrease was developed for the EG, both in the frequency of cannabis and/or other drug use as well as in heavy alcohol use, compared to the CG. No significant differences were found for the severity of alcohol, cannabis, and/or other drug use between the CG and EG. | A prevention programme aimed at reducing the use of alcohol, cannabis, and/or other drugs in Dutch adolescents with mild intellectual disabilities, borderline intellectual functioning, and delinquent behavioural problems helps to achieve a decrease in the frequency of cannabis and/or other drug use, as well as short-term heavy alcohol consumption. | No randomisation of participants in the study Small size of the participating sample Evaluation of short-term results The personality profiles sensation-seeking and impulsive behaviour were overrepresented |

| Butzer et al. (2017) | Aim: to test the short- and long-term effectiveness of Kripalu Yoga in Schools (KYIS), a yoga programme that aims to prevent and reduce risk factors for tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, and/or other drug use in US adolescents. | The usual physical education classes were held. Each session followed the following structure: (1) warming up (light jogging, aerobic movements, or muscle exercises); (2) playing games (relay races, jumping rope, aerobic exercises, etc.) or sports (football, volleyball, basketball, hockey, kickball, and wiffle ball); and (3) relaxation. | A modified 32-session version of the Kripalu Yoga in Schools (KYIS) programme was implemented. Each session followed the following structure: (1) warm-up (breathing and centring exercises); (2) yoga postures (warrior, triangle, sun salutations, etc.); (3) experiential didactic content (student-led yoga postures); and (4) relaxation (ocean breathing, three-part breathing, etc.). Throughout the sessions, yoga postures were gradually added with increasing rigour. All implemented sessions focused on mindfulness, self-regulation, and meditation. | CG participants were more willing to try cigarette smoking immediately after the intervention than EG participants. However, there were no significant differences in the willingness to use alcohol, cannabis, or other drugs between the two groups. No significant differences were found in any of the other variables either. The long-term results revealed improvements in emotional self-control for the female gender EG, as well as for the male gender CG. | Yoga at school has beneficial effects on willingness to smoke cigarettes while preventing risk factors related to the use of tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, and/or other drugs and developing improved emotional self-control in American adolescents. | Sampling bias due to consent/assent process in the study sample All of the outcome measures were self-reporting in nature, which may have led to bias and/or dishonesty in student responses Relatively small effect and sample size |

| Sidhu et al. (2016) | Aim: to investigate the short- and long-term effects of the tobacco prevention/cessation programme “Project-EX” with adolescent Indian students. | Standard care was provided, including tobacco prevention or cessation activities (if any) provided by the school. | A version adapted to the Indian context of the programme called “Project-EX”, based on the clinical programme (Sussman et al., 2001), was implemented. | A 100% smoking cessation rate was experienced, irrespective of status (CG/EG). Although the drop-out rate was not significant, there was a significant prevention effect in adolescents from the both the CG and EG. | A programme for Indian adolescents aimed at preventing/quitting tobacco use helps to strengthen their commitment to stay tobacco-free if they have never used it or stay tobacco-free if they have quit. | Lack of an evaluation related to the fidelity of the implementation (the only data collected by the facilitators were from the ratings of the participants) Limited intervention and evaluation periods (3 months follow-up) Reduced rate of self-reported tobacco use at the start of the study |

| Fishbein et al. (2015) | Aim: to assess the impact of a yoga intervention called “Hatha Vinyasa Flow” regarding the use of alcohol, cannabis, and/or other drugs and their psychological and psychophysiological correlates in US adolescents at a high risk of dropping out of school. | The students attended their regularly scheduled classes, with no active treatment (PA, PE, sports, etc.). | A version of mindful yoga was implemented based on guidelines by Miller et al. (2014), called “Hatha Vinyasa Flow”, which consisted of a sequence of basic yoga postures. Each session followed the following structure: (1) warm-up (breathing exercises, meditation, and centring); (2) stretching and gentle movements; (3) yoga postures (bending forward, backward, balancing, etc.); and (4) relaxation (meditation). Throughout the sessions, yoga postures were gradually added with increasing rigour. Each session concluded with an affirmation of respect for oneself and others. | A decrease in the frequency of alcohol, cannabis, and/or other drug use was found for the EG, as well as a higher use rate for those participants belonging to the CG. There was an increase in social skills in the EG participants, while they decreased for those in the CG. The same was true, albeit inversely, for stress level scores. No differences were found for mindfulness, emotional regulation, and behavioural self-regulation variables between the CG and EG participants. | Providing yoga in the school setting leads to a short-term decrease in alcohol use as well as improved social skills in US adolescents at risk of dropping out of school. | Potential biases in the reports obtained by the teaching staff The students self-selected themselves for the study and more than likely had some interest in yoga Small size of the participating sample |

| Espada et al. (2014) | Aim: to report on the short-term results provided by the smoking prevention/cessation programme “Project-EX” with Spanish adolescent students. | Standard care was provided, including tobacco prevention or cessation activities (if any) provided by the school. | A version adapted to the Spanish context of the programme called “Project-EX”, based on the clinical programme (Sussman et al., 2001), was implemented. | Significant differences were found in the levels of reduction in intention to smoke in those participants in the EG compared to those in the CG. Similarly, there was a lower level of nicotine dependence on the part of the EG, although not significantly so. Alternative medicine activities (yoga and meditation) received the highest satisfaction scores from EG participants. | An intervention for Spanish adolescents aimed at preventing/quitting tobacco use helps to strengthen, in the short term, their commitment to remain tobacco-free if they have never used or to remain tobacco-free if they have already quit. Above all, it shows potentially more promise in preventive measures. | Limited intervention and evaluation periods Lack of an evaluation related to the fidelity of the implementation The study only pertains to immediate effects Recruitment was not easy in Spanish high schools because of low motivation among staff to add extra-curricular activities in the schedule The dropout rate at immediate postprogram questionnaires was 22.2% |

| Melnyk et al. (2013) | Aim: to test the short- and long-term effectiveness of an intervention aimed at preventing alcohol and cannabis use, consisting of a dual programme: “COPE (Creating Opportunities for Personal Empowerment)” and “Healthy Lifestyles TEEN (Thinking, Emotions, Exercise, Nutrition) Program”, versus a control condition programme called “Healthy Teens”, with US adolescents. | The “Healthy Teens” programme was carried out, focusing on health and safety aspects (dental care, infectious diseases, etc.). | A unified version of the “COPE” and “Healthy Lifestyles TEEN” programmes focusing on educational and cognitive behavioural skill development was implemented, with an integration of PA (walking, kick-boxing movements, dancing, etc.) as a component of each session. | A significant reduction rate in alcohol consumption was experienced for EG participants. More favourable scores for BMI, social skills, and academic performance were also obtained for this group. On the other hand, anxiety and depression scores were reduced in both CG and EG. After the six-month intervention, all variables remained the same or developed beneficially, with the exception of the levels of cannabis use, which increased in both groups. | A dual intervention programme aimed at preventing substance use improves both short- and long-term outcomes of healthy living, academic performance, and alcohol use in US adolescents. | Deviations obtained in intervention fidelity scores. The two groups of students differed on some variables at baseline (e.g., weight, TV viewing time). |

| Sun et al. (2007) | Aim: to investigate the short-term effects of a tobacco prevention/cessation programme called “Project EX” with US adolescent students. | Standard care was provided, including tobacco prevention or cessation activities (if any) provided by the school. | A school-adapted version of the “Project-EX” programme was implemented, based on the clinical programme (Sussman et al., 2001). | Significant differences were found in the reduction in smoking intention/use-related levels in participants from all EGs compared to those from CGs. Levels of substance use knowledge significantly increased in a positive manner for participants in all EGs. | An intervention for American adolescents aimed at preventing/quitting tobacco use helps to strengthen, in the short term, their commitment to remain tobacco-free if they have never used or to remain tobacco-free if they have already quit. | Generalisation of findings, limited to a population with restricted access to pre-measurement of the intervention |

| Collingwood et al. (2000) | Aim: to test the short-term efficiency of implementing physical training exercises through the “First Choice” programme as a prevention intervention for the abuse of tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, and/or other drugs in adolescents from US schools and community centres in environments at risk of exclusion. | This study did not have a comparison CG. | The “First Choice” fitness programme was implemented, based on personal training and learning values and life skills through exercise. | A reduction in the number of participants who were previously substance users was experienced in all intervention groups. In addition, there was an increase in physical fitness in participants in all intervention groups, as well as higher levels of PA performed and a reduction in risk factors related to the abuse of tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, and/or other drugs, although these were more significant for participants belonging to the community centre EGs. | The “First Choice” fitness programme is seen as a practical intervention for the prevention and short-term treatment of tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, and/or other drug use behaviours, as well as for increasing PA levels in US adolescents at risk of exclusion. | The priority for school and service agencies serving these youth is programme delivery, not evaluation Low rate of study participants who provided feedback on the data obtained Self-reported data from survey participants Non-existence of an untreated CG |

| Goldberg et al. (2000) | Aim: to examine the short- and long-term effectiveness of a gender-specific, football team-focused programme designed to reduce intentions to use anabolic steroids, alcohol, and/or other drugs (cannabis, amphetamines, or narcotics) in US adolescent athletes. | A pamphlet (Beete, 1994) was administered, containing generic prevention and health promotion material. This pamphlet emphasised the adverse effects of the use of anabolic steroids, alcohol, and other drugs (cannabis, amphetamines or narcotics) in sports, as well as the benefits of a correct sports nutrition diet. | A programme integrating two components was implemented: (1) Classroom plan: the negative effects of the use of anabolic steroids as well as the use of alcohol and other drugs (cannabis, amphetamines or narcotics) in sports were addressed. In addition, information on sports nutrition was provided through a guide with suggested meal plans. (2) Strength training: Group strength training sessions (6–8 participants) were held in the weight room. | Intention to use alcohol and/or other drugs (cannabis, amphetamines, and narcotics) was not reduced through short-term effects. On the other hand, improvements were shown with regard to the knowledge acquired in relation to the use of anabolic steroids, alcohol, and other drugs (cannabis, amphetamines, and narcotics), resulting in higher levels of healthy behaviours among participants of all EGs. Twelve months after the intervention, all variables had similar scores, except for intention to use alcohol and/or other drugs (cannabis, amphetamines, and narcotics), which did decrease for participants in all EGs. | An anabolic steroid, alcohol, and/or other drug (cannabis, amphetamines, and narcotics) prevention programme produces both short- and long-term improvements in the acquisition of healthy behaviours and decreases the intention to use these substances in US adolescent athletes. | Self-reported data from survey participants Study power was limited as anabolic steroid use was lower than expected |

| Collingwood et al. (1991) | Aim: to assess the short-term effectiveness of physical training (as an integrated element in the programming of an intervention) for substance-abusing adolescents participating in tobacco, alcohol, and/or cannabis prevention settings (based on secondary school) and treatment (community and health centre (hospital)). | This study did not have a comparison CG. | A physical fitness programme was implemented, both for participants in each intervention group as well as for their parents, guardians, or legal caregivers. The intervention focused on three main components: (1) fitness and exercise training programme; (2) parent training; and (3) computerised fitness assessment system with built-in reinforcement for participants. Regardless of the intervention group, all participants received the same fitness programme modules and exercise prescription. | There was a reduction in the number of participants who previously used tobacco, alcohol, and/or cannabis, as well as an increase in abstention in all intervention groups, although these were not significant. There was also a reduction in risk factors related to substance abuse (tobacco, alcohol, and/or cannabis), as well as an increase in the level of physical fitness in all participants belonging to the three EGs, although these data were not significant either. | A physical fitness programme is considered an effective short-term intervention for preventing and reducing substance use (tobacco, alcohol and/or cannabis), as well as helping to reduce risk factors for substance use and increase PA levels in adolescents at high risk of social exclusion. | Small size of the participating sample Self-reported data from survey participants Non-existence of an untreated CG Factors such as test or protocol familiarity and lack of initial motivation, often symptomatic with this population, could have affected underestimated baseline scores for the sample |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Carrellán, J.Á.M.; Robles, M.T.A.; Giménez-Fuentes-Guerra, F.J.; Macías, M.R. Educational Interventions Through Physical Activity for Addiction Prevention in Adolescent Students—A Systematic Review. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 348. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030348

Carrellán JÁM, Robles MTA, Giménez-Fuentes-Guerra FJ, Macías MR. Educational Interventions Through Physical Activity for Addiction Prevention in Adolescent Students—A Systematic Review. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(3):348. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030348

Chicago/Turabian StyleCarrellán, José Ángel Mairena, Manuel Tomás Abad Robles, Francisco Javier Giménez-Fuentes-Guerra, and Manuel Rodríguez Macías. 2025. "Educational Interventions Through Physical Activity for Addiction Prevention in Adolescent Students—A Systematic Review" Education Sciences 15, no. 3: 348. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030348

APA StyleCarrellán, J. Á. M., Robles, M. T. A., Giménez-Fuentes-Guerra, F. J., & Macías, M. R. (2025). Educational Interventions Through Physical Activity for Addiction Prevention in Adolescent Students—A Systematic Review. Education Sciences, 15(3), 348. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030348