Abstract

In addition to being influenced by structural factors like socioeconomic background (SES), children’s achievements are also influenced by psychological factors like the parental mindset. Mindsets may thus be a key to tempering the income–vocabulary gap in emerging bilingual children’s L1 and L2 vocabulary. This study compared how SES and the parental mindset connect with parental values on the importance of English, home literacy practices, and children’s Chinese and English vocabulary. We assessed 271 (Mage = 60.78 months) children’s Chinese and English vocabulary, and their parents completed a home literacy environment questionnaire. Path analysis showed that parental growth mindset does not vary with their SES. In addition, parents’ mindsets have a unique contribution to children’s outcomes through parents’ beliefs and the home literacy environment.

1. Parental Mindset and SES: Mitigating Income–Vocabulary Gap in Early Childhood of Emergent Bilinguals

In the home literacy environment (HLE), parents play a paramount role in children’s early language development (Penderi et al., 2023; Sénéchal & LeFevre, 2014). Parents engage with children’s learning through the provision of an enhanced literacy environment (Griffin & Morrison, 1997), active participation, and “interactionally supportive, linguistically adapted, and cognitively challenging” interactions (Rowe & Snow, 2020, p. 5). Indeed, accumulating evidence has confirmed that structural factors in the home literacy environment like parents’ SES, educational background and home literacy practices can predict children’s literacy development (Hood et al., 2008; Sohr-Preston et al., 2013). These structural factors are essential in bilingual language development (Li et al., 2023; Westeren et al., 2018; Zhao & Dixon, 2024). However, the cascading effects of SES on children’s literacy development generate income–reading gaps, leading to educational inequality (Reimer et al., 2021; Su et al., 2021). This calls for a new strand of research to explore psychological variables that concern children’s early literacy development (e.g., Butler, 2019; Lai et al., 2024), in which the salience of parents’ mindsets has been identified (Rowe & Leech, 2019).

The concept of a mindset derives from implicit theories (Hong et al., 1999), referring to perceptions of the malleability of human attributes (e.g., intelligence, personality, ability). Along the spectrum of mindsets, a person’s mindset ranges from a fixed mindset (believing that intelligence is pre-determined and cannot be improved) to a growth mindset (a belief endorsing the changeability of intelligence). Evidence from empirical studies indicates a relationship between parents’ mindsets and children’s language learning outcomes including receptive vocabulary (Leyva et al., 2024; Rowe & Leech, 2019; Song et al., 2022).

When it comes to how parents’ mindsets influence children’s literacy development, researchers have suggested two paths: first, children imitate their parents’ mindsets and change their behaviors accordingly to enhance their achievements (Haimovitz & Dweck, 2017); second, the parental mindset affects their behaviors that then affects the children’s level of achievements (Matthes & Stoeger, 2018). In addition, Hong et al. (1999) hypothesized that a mindset brings beliefs and behaviors into a meaning system where they interact with each other. A mindset interconnects with other beliefs such as attributions (Diener & Dweck, 1978) and effort beliefs (Miele et al., 2013) to build a motivational system that guides behaviors such as the willingness to take challenges (e.g., Dweck & Leggett, 1988), reactions towards errors (Moser et al., 2011), resilience (Yeager & Dweck, 2012), and the adoption of self-regulated learning (Bai & Wang, 2020). These behaviors then in consequence decide children’s achievements. In other words, mindsets directly predict other motivational factors (e.g., effort belief), which in turn predict behaviors and then influence achievements (e.g., West et al., 2018).

However, many of these studies have been conducted in the L1 learning context, and this argument might be at the level of speculation in the L2 learning context as there is little empirical support. English learning in China presents a unique context as China has the largest emerging bilingual population. English is typically introduced as a compulsory subject from Grade 3 in the Chinese mainland. In China, despite the integration of English into the curriculum, students often have limited exposure to the language both inside and outside the classroom. This limited exposure, coupled with the rapid pace of globalization, has led to disparities in English learning opportunities, especially across socioeconomic strata. For instance, children from high socioeconomic status (SES) families in China are beginning to learn English at earlier ages, while those from disadvantaged backgrounds often have minimal access to English learning resources (Butler, 2015). The impact of SES on children’s L2 vocabulary development is even more pronounced than in their L1, widening the vocabulary gap. This study compares the role of parental mindsets and SES in Chinese and English vocabulary acquisition, aiming to offer strategies for mitigating these disparities. Despite these challenges, the pursuit of English proficiency remains a key priority for many Chinese families, reflecting its perceived role in achieving personal and professional success in an increasingly globalized world.

1.1. Children’s Mindset and Their L2 Learning

While children’s fixed language mindset cannot significantly predict their L2 reading achievement, research suggests that a growth language mindset can have a positive impact on their L2 reading achievement (Khajavy et al., 2021). This favorable association between a growth mindset and L2 achievement is theorized to be influenced by children’s behaviors, as those with a growth mindset are more inclined to persist in learning and exert greater effort when faced with setbacks and challenges (Dai & Cromley, 2014). In a study by Hong et al. (1999) conducted at the University of Hong Kong, students were surveyed regarding their willingness to enroll in a course aimed at enhancing their English proficiency, their L2. The results revealed that students characterized by a fixed mindset exhibited limited interest in the course, even when they lacked proficiency in English. In contrast, students embracing a growth mindset, despite their English proficiency levels, displayed greater eagerness to participate in the course. This divergent behavior was suggested to have implications for their subsequent English language proficiency levels.

In addition, the pathway from mindset to beliefs and home literacy practices to language performance was also validated. Researchers elucidated the importance of subject task values (Eccles et al., 1993) in the path from mindset to L2 language acquisition. The subject task values encompass utility value (the perceived usefulness of the skill), intrinsic value (personal enjoyment in learning the skill), and value of importance (the perceived importance of the skill). Per the expectancy–value theory, these task values play a pivotal role in shaping children’s behaviors, subsequently influencing their academic achievements (Wigfield & Eccles, 2000). Eren and Raktatiğlu-Söylemez (2020) showed that utility value fully mediated the effects between students’ mindset about second language aptitude and language performance. In addition, children’s learning behavior partially mediated the relation between utility value and academic performance. While previous studies have explored the connections between utility value, mindset, and behaviors (Eren & Raktatiğlu-Söylemez, 2020), the role of the value of importance—an underexplored motivational predictor of students’ language learning—remains unexamined. Durik et al. (2005) utilized a culturally diverse sample including Asian Americans to investigate the relationship between students’ value of importance and their reading behaviors in the 4th grade, as well as their English performance in the 10th grade. The findings revealed that the value of importance predicted the number of English classes students opted to take (see also Simpkins et al., 2012), a decision that subsequently impacted their literacy skills and English language development. This underscores the critical role of motivational factors such as the value of importance in shaping students’ language learning journeys and academic outcomes.

While research on children’s growth mindset is extensive, studies examining the connection between the parental mindset and their children’s language skills are limited (Moorman & Pomerantz, 2010). Considering the significant role parents play in molding the home literacy environment, recent research efforts have started to investigate how parental mindsets influence children’s literacy development (Andersen & Nielsen, 2016; Matthes & Stoeger, 2018; Muenks et al., 2015). Exploring the interplay of the parental mindset with language acquisition could provide valuable perspectives for enhancing early literacy interventions.

1.2. Parents’ Mindsets and Children’s Language Learning

Studies have suggested a beneficial impact of parents’ mindsets on the language skills of their children (Andersen & Nielsen, 2016; Leyva et al., 2024; Matthes & Stoeger, 2018). For example, Andersen and Nielsen (2016) implemented a cost-effective intervention toward parents’ mindsets. This intervention aimed at educating parents on the importance of a growth mindset, providing them with reading materials and encouraging them to praise their preschool children’s efforts during shared reading activities. The results showed that children whose parents had received reading intervention with a growth mindset approach had improved reading comprehension.

Furthermore, research has highlighted the impact of parents’ mindsets on their parenting behaviors (e.g., Dweck & Master, 2008; Moorman & Pomerantz, 2010; Muenks et al., 2015). Parents with a growth mindset were more likely to exhibit effective learning-related behaviors (Dweck & Master, 2008). This is because parents with a growth mindset value the mastery of learning more than learning outcomes. Such parents focus on supporting their children in overcoming learning challenges rather than solely emphasizing outcomes (Grolnick, 2003). In contrast, parents with fixed mindsets display less autonomy-supportive and mastery-oriented parenting behaviors when engaging with children’s learning (Moorman & Pomerantz, 2010; Muenks et al., 2015). Matthes and Stoeger (2018) recruited 723 German parents and investigated parents’ mindsets, children’s mindsets, and parents’ behaviors, as well as children’s academic grades in German, mathematics, and basic science. The results showed that a parental growth mindset increased students’ grades by increasing parents’ constructive behaviors in learning. Muenks et al. (2015) also provided evidence for relationships between the parental mindset and the home literacy practices they adopted. Muenks et al. (2015) analyzed 386 parents’ online questionnaires and found that parents’ mindsets predicted the quality and the frequency of their reading participation.

The relationship between mindset and home literacy practices is influenced by additional motivational factors, such as beliefs, in various research studies. Muenks et al. (2015) recruited 86 parents to examine the mediation effects of parents’ efficacy (parents’ beliefs about their capability to enhance their children’s skills) on the relationships between parental growth mindset and parental behaviors in home literacy practices. The findings suggest that parental efficacy partially mediated the relation between the fixed mindset and performance-oriented behaviors in the reading. Likewise, Matthes and Stoeger (2018) have argued that the association between parents’ mindsets and children’s learning outcomes is mediated by parents’ beliefs and home literacy practices and tested the mechanism underlying such an association.

To the best of our knowledge, Matthes and Stoeger’s (2018) study was the first to reveal the mechanisms underlying the association between parents’ mindsets and children’s L1 achievement. However, as mentioned earlier, this study was conducted in a context where children’s learning outcomes were measured through their grades in German, mathematics, and basic science. Little is known, for instance, about whether these mechanisms are valid in the context of vocabulary acquisition, especially among families that value both L1 and L2 learning in children’s early literacy development.

1.3. English Language Learning in the Chinese Context

In today’s globalized world, the intersection of English language learning and Chinese language practices presents unique challenges and opportunities, particularly within the Chinese educational context. The Chinese government has long emphasized English education as a critical component of the national curriculum from primary school through university. Since the late 1970s, English has been a compulsory subject in China’s Gaokao (national college entrance exam), underscoring its role in academic and career advancement. In recent years, policies such as the “Double Reduction” policy (2021) have sought to reduce the academic burden on students, including limiting after-school English tutoring, while still maintaining English’s prominence in formal education. Beyond schools, English proficiency is highly valued in the job market, particularly in industries like technology, finance, and international trade.

However, English learning in China also faces challenges, including disparities in educational resources. In China, early exposure to English before formal education, which typically begins around Grade 3, varies significantly depending on factors such as SES, parental values toward English, and access to resources. Families with better access to resources often provide their children with extensive English learning opportunities, such as private tutors, bilingual kindergartens, English-language books, and digital learning tools (Sun et al., 2016). They may also hire native English-speaking tutors or enroll their children in international preschools, and some families even facilitate exposure through travel abroad. In contrast, families with limited financial resources often rely on free or low-cost options like public libraries, online videos, or community programs, and parental involvement may be constrained by their own English proficiency. Chen et al. (2020) showed that children from mid-to-high SES backgrounds start to learn English before primary school, and they gain a more positive learning attitude and better grades later in l-3 grades compared with children who have no exposure to English before school. Parental attitudes play a crucial role as well; parents who value English as essential for future success tend to be actively engaged in their children’s early English learning by reading English books, singing songs, or watching English cartoons together. On the other hand, parents who prioritize Mandarin or view English as less critical may focus less on early English exposure. Geographic location also influences access to resources, with urban areas offering more English learning opportunities compared to rural regions. Overall, early English learning in China is highly uneven, reflecting disparities in SES, parental values, and regional development.

1.4. The Present Study

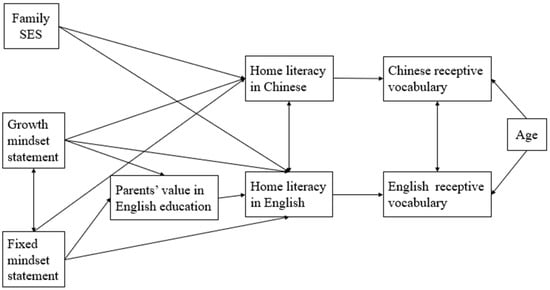

Understanding the pathways through which a parental mindset influences children’s vocabulary attainment in a second language learning context remains incomplete. A paucity of findings on the role of noncognitive factors in SLA such as mindset (Lou & Noels, 2019) and task values (Loh, 2019) warrants attention. To address this research gap and enrich the literature, this study aims to investigate the inherent relationships between the influence of parents’ general mindset regarding intelligence and children’s vocabulary development in both languages. Based on the framework proposed by Matthes and Stoeger (2018) and Hong et al. (1999), this study examines how a parental mindset relates to two key aspects: (1) how much parents value English (motivational factors) and (2) their home literacy practices in both languages (behaviors). In addition, this study also compares the connections between SES and parental mindsets in children’s vocabulary learning, hoping that mindset is a psychological factor that buffers children’s word gap in L1 and L2. The hypothesized model is presented in Figure 1. The two aspects can be summarized into the following questions:

Figure 1.

Hypothesized path model illustrating the relationship among family SES, parents’ mindsets, parents’ values in early English education, home literacy practices, and receptive vocabulary in Chinese and English.

- How does the parental mindset about intelligence influence children’s Chinese and English vocabulary?

- How does SES influence children’s Chinese and English vocabulary?

2. Method

2.1. Participants

We obtained permission to recruit participants from two private kindergartens in a metropolitan city in southern China. Paper consent forms were sent to parents by classroom teachers. Parents who agreed to participate in the present study sent back the signed consent forms to classroom teachers.

We, in total, recruited 271 families, with children aged between 35 and 83 months old (M = 60.78, SD = 10.28); however, due to the age limit of the measurement of Chinese receptive vocabulary, which was targeted at children aged beyond 39 months old, five children were removed from the present study. Among the child participants, 144 (53.1%) of the children were boys and 127 (46.9%) were girls. All the children spoke Chinese as their L1 and learned English as L2. The kindergarten or parents reported no known developmental or language delays. Kindergartens did not offer English classes, so children learned English either at home or in extra-curricular commercial English classes. Most parents (90.8%) reported that their children were not exposed to offline commercial English classes outside home or school, and some parents reported that children had little knowledge about English (37.6%) or possessed a limited English vocabulary size (56.5%). Among these children who had started to learn English, the median age of starting to learn was 36 months old.

Children of the present study were from families across SES levels in the Chinese city, according to Shenzhen Statistical Yearbook 2020 (Shenzhen Statistics Bureau, 2020) where the per capita monthly disposable income in 2019 was RMB 5210.02. The monthly income of 31.7% of families ranged from RMB 5000 to 10,000, 35.8% of families earned between RMB 10,000 and 20,000 per month, 15.9% of families had a monthly income between RMB 20,000 and 30,000, and 9.6% of families had a monthly income of RMB 30,000 or above. The education attainment of most parents was below a bachelor’s degree: 18.8% of fathers and 19.2% of mothers received lower secondary education or below; 30.6% of fathers and 28.4% of mothers received upper secondary education; and 28.8% of fathers and 38.4% of mothers attained a post-secondary level of education. In addition, 20.3% of fathers and 14.0% of mothers attained a bachelor’s degree; 1.5% of fathers possessed a master’s degree.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Family Socio-Economic Status (SES)

Family SES was indexed with paternal education attainment, maternal education attainment, and household monthly income. Parents reported their highest education attainment from 1 = secondary school and below to 6 = doctoral degree. Household monthly income was measured with a five-point scale from 1 = 5000 RMB and below to 5 = 30,000 RMB and above. The Cronbach alpha for internal consistency measuring family SES was 0.71. We used the total score of paternal education, maternal education, and family income to indicate the level of SES among participating families.

2.2.2. Parental Mindset About Intelligence

We adapted and translated Dweck’s (1999) Theories of Intelligence Scale to measure parents’ mindsets on whether child intelligence was malleable. This form has commonly been used by previous studies to investigate one’s intelligence mindset (e.g., Claro et al., 2016; Thoman et al., 2020; Zhang et al., 2024). In our study, the form included four statements that examined parents’ fixed mindset that child intelligence is not malleable (e.g., “Your child has a certain amount of intelligence, and you can’t do much to change it”) and four statements on parents’ growth mindset that child intelligence is malleable (e.g., “You can always substantially change how intelligent your child is”). Parents responded on a 6-point Likert scale from 1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree. We examined parents’ fixed mindsets and growth mindsets separately, and the scores for these two subscales were the total scores of the corresponding four items. We assisted the parents in filling in the questionnaire onsite, encouraged parents to ask any question while they were filling out the questionnaires, and made sure their questions were answered. We also sent out trials beforehand to obtain potential feedback from parents, and it showed that they understood the items well. Finally, we excluded parents who selected the same answer on every item in the data screening phase to ensure the score reliability.

2.2.3. Home Literacy Practices

The home literacy practices in Chinese were measured with five questions on a five-point scale, concerning the number of Chinese picture books at home, the frequency of shared book reading, the frequency of watching Chinese cartoons, and the frequency of listening to Chinese songs. The total score of the five question items was employed as an indicator of home literacy practices in Chinese. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.70.

The home literacy practices in English were assessed with a total of seven questions on a five-point scale. They included the number of English picture books, the frequency of shared book reading, the frequency of watching English cartoons, and the frequency of listening to English songs. Additional questions addressed the frequency of parents teaching English, as English is a second language and is not used daily (Bolton & Graddol, 2012): (1) “How often do you read out English words in the surroundings to your children voluntarily? (e.g., when you see Pizza Hut or MacDonald’s, you will read it out to your children.)”; and (2) “How often do you encourage your child to use learned English vocabulary and sentences in daily conversation?” The total score of the seven questions was used as an indicator of home literacy practices in English. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.78.

2.2.4. Parents’ Value of Early English Education

We asked parents the extent to which learning English from an early age was important for their child. Parents responded with a 5-point scale from 1 = very unimportant to 5 = very important. Parents rated the importance of English by responding to two items. The two items have been validated in existing studies (Eccles et al., 1993; Parsons et al., 1984).

2.2.5. English Receptive Vocabulary

The Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test—Fourth Edition (PPVT-4; Dunn & Dunn, 2007) was used to measure children’s English receptive vocabulary. The test contained a total of 228 items, with every 12 items as a set. Items were arranged with increasing difficulty and lower frequency, and the test stopped when children gave eight wrong answers in a set, also called the ceiling set. For each item, children were expected to point to one of the four colored pictures corresponding to the meaning of the word verbally presented by the examiner. For instance, when the examiner said “ball”, children should point to the picture with a ball among the other three pictures without carrying the meaning of “ball”. The raw score was calculated by subtracting the total number of errors from the last item of the ceiling set. Most children knew words such as “ball”, “dog”, and “banana”, whereas those with larger vocabulary sizes knew words like “turtle”, “painting”, and “squirrel”. The test reliability was reported to be high, with the split-half reliability ranging from 0.89 to 0.97 and the test–retest reliability ranging from 0.92 to 0.96 for different age groups (Frey, 2018). The internal consistency for the current study was 0.70.

2.2.6. Chinese Receptive Vocabulary

Children’s receptive vocabulary in Mandarin Chinese was measured with the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test—Revised (PPVT-R; Sang & Miao, 1990), which was developed based on the PPVT-R developed in English and was validated via a Chinese-speaking representative sample aged from 3.5 to 9 years old in Shanghai, with the split-half internal consistency being 0.98 and test–retest reliability being 0.94 (Sang & Miao, 1990). Children were orally presented with Chinese words and were instructed to point to one of the four presented pictures that best matched the word’s meaning. The test was arranged with words of increasing difficulty and lower frequency. We proceeded with further analysis with the standardized score according to the children’s age. The Cronbach’s alpha in our study was 0.70

2.3. Procedure

Parents completed an online questionnaire distributed by kindergarten teachers in the online class groups, touching on family demographics, home literacy practices, parents’ mindsets, and parents’ values of English education. The Chinese receptive vocabulary test and English receptive vocabulary test were administered by one of the researchers and another trained graduate student in a quiet room in the kindergarten after the children finished their day at kindergarten. The two tests lasted for approximately 20 min, and children were offered a break between the tests.

2.4. Data Analysis

We conducted a path analysis on Mplus 8 to examine our hypothesized model (Muthén & Muthén, 2017). We first screened univariate outliers for each investigated variable by looking into the sample median and the median absolute deviation (MAD), which refers to the median of sample scores from the sample median. The formula shows the method of using MAD to detect outliers. The value obtained from the formula shows the distance of sample scores from the MAD. A value greater than the constant of 2.24, which is the “square root of the approximate 97.5th percentile in a central χ2 distribution with a single degree of freedom” (Kline, 2016, p. 72), indicates the presence of an outlier. This method of detecting outliers is more reliable and robust than examining whether sample scores are within three standard deviations from the mean, which is more sensitive to the presence of extreme values than the median and thus masks the detection of extreme values that should be outliers (Kline, 2016; Leys et al., 2013). We found a small percentage of outliers in most variables (1~5%), which were handled by converting them to the next extreme value that was within three standard deviations of the mean score. The large percentage of outliers in the English receptive vocabulary test (21%) were handled with logarithm transformation. We also examined multivariate outliers via the Mahalanobis distance, and we found no multivariate outliers.

By screening parents’ responses to the questionnaire, we detected 41 parents giving identical responses to all eight question items in the scale of the parental mindset about intelligence, which might indicate that these parents did not make an effort to complete this scale thoughtfully, so we removed these responses from this scale, leading to 41 missing cases in the parental mindset. We also found two missing values from the Chinese receptive vocabulary test due to absence from school. We handled data missingness with a full information maximum likelihood estimation. In addition, we screened variables with the largest or smallest variance to avoid an ill-scaled covariance matrix where the ratio of the largest to smallest variance was beyond 100. Large differences in variance magnitude might induce biased model estimates toward worse model fits (Kline, 2016). We found large variances in Chinese receptive vocabulary and children’s age by month and adjusted them by multiplying the scores by the constant 0.01.

Due to the presence of an endogenous ordered categorical variable, which is parents’ value in early English education, we employed weighted least square parameter estimates (WLSMV) and theta parameterization in path analysis. The cutoff criteria for model fit indices were not available for WLSMV estimation, so we assessed the hypothesized model with cutoff criteria for maximum likelihood estimation including the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) < 0.06, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) CFI > 0.95, and the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) > 0.95 (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Pan & Lin, 2023). Since the cutoff criteria of model fit indices for maximum likelihood estimation might not be generalizable to WLSMV (Xia & Yang, 2019), we also tried to validate our research findings by employing alternative maximum likelihood estimation (MLR) by treating the ordered categorical variable (i.e., parents’ value in early English education) as a non-normal continuous variable to produce standard errors that were robust to non-normality.

3. Results

Table 1 shows the minimum score, maximum score, means, and standard derivations of all investigated variables. Overall, parents’ SES showed wide variability, and parents reported a higher level of participation in children’s early literacy development in Chinese than in English. Children’s standardized score in Chinese receptive vocabulary suggested that, on average, children’s Chinese receptive vocabulary was at the 30th percentile of the population (Sang & Miao, 1990). The raw score of English receptive vocabulary indicated that while a few children showed a large vocabulary size in English, most children possessed limited English receptive vocabulary measured by the PPVT-4. The mean score of parents’ fixed mindsets suggested that on average, parents disagreed or somewhat disagreed that they could not change their child’s intelligence (e.g., “Your child has a certain amount of intelligence, and you can’t do much to change it”). Similarly, the mean score of parents’ growth mindset statements showed that more than half of the parents somewhat agreed with the malleability of a child’s intelligence (e.g., “No matter how much intelligence your child has, s/he can always change it quite a bit”). More than half of the parents agreed that early English education was important to their children.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of measured variables.

Table 2 presents the results of bivariate correlational analyses among all studied variables. The results showed that children’s Chinese receptive vocabulary was moderately and positively correlated with age, r = 0.38, p < 0.001, and weakly correlated with home literacy environment in Chinese, r = 0.16, p = 0.01, and family SES, r = 0.16, p = 0.01. Children’s English receptive vocabulary was weakly correlated with children’s age, r = 0.13, p = 0.04, and it showed a stronger correlation with home literacy environment in English, r = 0.28, p < 0.001, and family SES, r = 0.20, p = 0.002. Family SES showed a stronger correlation with home literacy environment in Chinese, r = 0.38, p < 0.001, than with home literacy environment in English, p = 0.27, p = 0.00. Home literacy environment in English was also positively and moderately correlated with parents’ value in early English education, r = 0.26, p < 0.001, which was positively correlated with parents’ growth mindsets, r = 0.19, p = 0.01. Parents’ fixed mindsets and growth mindsets were weakly and negatively correlated, r = −0.15, p = 0.004. Parents’ fixed mindsets showed no statistically significant correlation with other variables.

Table 2.

Correlation coefficients among all investigated variables.

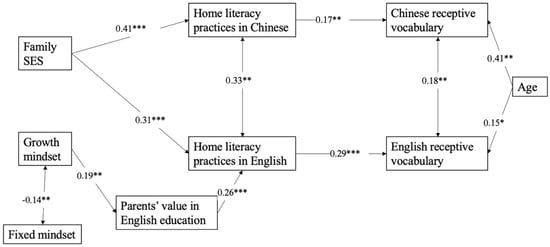

Based on the hypothesized model illustrated in Figure 1 and the results of the correlation analysis, we removed the hypothesized prediction from the growth mindset to home literacy practices in Chinese and English. We also removed the path from the fixed mindset to all mediators, as it did not show correlations with any variable except the growth mindset. As shown in Figure 1, we treated children’s English receptive vocabulary and Chinese receptive vocabulary as dependent variables. We imputed family SES and the parental mindset about intelligence, represented by the parental growth mindset, as independent variables. Home literacy practices in Chinese, home literacy practices in English, and parents’ value in English education were treated as mediators.

The hypothesized model estimated with WLSMV yielded an adequate model fit: χ2(24) = 33.89, p = 0.09, RMSEA = 0.04, CFI = 0.94, and TLI = 0.92. Cross-validation from MLR showed similar results: χ2(24) = 30.80, p = 0.16, RMSEA = 0.03, CFI = 0.96, and TLI = 0.95. Figure 2 illustrates the final path model with standardized estimates of path coefficients under WLSMV estimation. The modified model accounted for 16% of the variance in Chinese receptive vocabulary and 11% of the variance in English receptive vocabulary. As Figure 2 illustrates, parents’ growth mindset was a statistically significant predictor of their values in the importance of early English education, b* = 0.19, p = 0.008. Both family SES, b* = 0.31, p < 0.001, and parents’ values in English education, b* = 0.26, p < 0.001, statistically significantly predicted home literacy practices in English, which further predicted children’s receptive vocabulary in English, with children’s age controlled for, b* = 0.29, p < 0.001. Family SES was also a statistically significant predictor of home literacy practices in Chinese, b* = 0.41, p < 0.001. Home literacy practices in Chinese predicted children’s Chinese receptive vocabulary, b* = 0.17, p = 0.001, with children’s age controlled for.

Figure 2.

Final path model with standardized path coefficients illustrating the relationship among family SES, parents’ growth mindset, parents’ value in early English education, home literacy practices, and receptive vocabulary in Chinese and English. Note: * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

To examine whether parents’ mindsets and values and family SES were indirectly associated with children’s language outcomes via the mediation of home literacy practices, we conducted mediation analyses with the bias-corrected bootstrapping of 2000 resamplings. Confidence intervals (CIs) not including zero indicate a statistically significant indirect effect with 95% probability. The results showed a statistically significant indirect effect of family SES on children’s receptive vocabulary in Chinese via the mediation of home literacy practices in Chinese, b* = 0.07, 95% CIs [0.02, 0.14]. Similarly, family SES indirectly related to children’s English receptive vocabulary via the mediation of home literacy practices in English, b* = 0.09, 95% CIs [0.03, 0.17]. Parents’ growth mindset shows marginal statistical significance in the indirect effect on children’s English receptive vocabulary via the mediation of parents’ value in early English education and home literacy practices in English b* = 0.02, 95% CIs [0.00, 0.04].

4. Discussion

In alignment with previous studies (e.g., Coddington et al., 2014; Hart & Risley, 1995), this study revealed that SES influenced children’s vocabulary sizes in both L1 (Chinese) and L2 (English) through home literacy practices in both languages. Families from higher SES backgrounds promote their children’s vocabulary through richer home literacy practices. In addition, our results indicate that the magnitude of the effect of children’s family SES varies between their Chinese home literacy practices and their English home literacy practices. Notably, family SES exerts a more pronounced impact on Chinese home literacy activities than on English home literacy activities. One plausible explanation is the complexity of factors influencing English home literacy practices compared to those affecting Chinese home literacy activities. For example, the parental value of the importance of English is positively related to English home literacy practices in this study, which supports that English home literacy practices are influenced by more factors than Chinese home literacy practices.

Another finding is that English home literacy practices exhibit a greater influence on children’s English vocabulary compared with the effects of Chinese home literacy on Chinese vocabulary. Chinese is continuously practiced and used in daily life without necessitating extensive external resources or specialized training, especially in such a metropolitan city as Shenzhen, where preschoolers are required to use Mandarin in kindergartens with teachers and their peers. English learning, however, relies on more external factors such as English input quantity (e.g., English media, books, and games used at home and school) than on internal factors such as the age of onset (Sun et al., 2016). English exposure in a natural or daily environment is scarce for preschoolers. Thus, home literacy practices in L2 play a more important role in children’s literacy acquisition than home literacy practices in L1 do.

Regarding the role of the parental mindset about intelligence, previous studies have investigated how the parental mindset about intelligence influenced academic domains like mathematics and science (Matthes & Stoeger, 2018) and how the parental mindset about language influenced children’s language performance (Eren & Raktatiğlu-Söylemez, 2020). This study contributed to previous studies by investigating how the parental mindset about intelligence influenced children’s vocabulary. It was found that no direct relationship exists between the parental mindset about intelligence and children’s vocabulary in both languages. This result is consistent with previous studies on the influence of children’s mindset on their academic achievement (Holden & Goldstein, 2024; Laurell et al., 2022). This lack of direct relation can be due to parents’ lack of urgency in bridging the vocabulary gap (Haimovitz & Dweck, 2017). When parents do not recognize the urgency of addressing the vocabulary gap, they will not consistently support their children’s learning endeavors. Additionally, unlike intervention studies (e.g., Andersen & Nielsen, 2016), in a natural setting, although parents acknowledge the potential for improving children’s intelligence, they do not know the requisite strategies to effectively facilitate this enhancement. This finding underscores that just believing intelligence can be enhanced is not sufficient for parents; they also need to translate this belief into practice. Moreover, according to the meaning system (Hong et al., 1999), it is the interaction between mindsets and related motivational constructs (e.g., task value, self-efficacy, and interest) that impacts children’s achievements. When other motivational mediators are absent, mindset alone will not influence achievements.

This can be supported by the finding that parental growth mindset about intelligence can influence children’s English vocabulary through the importance parents place on English. This value subsequently impacts the home literacy practices parents adopt, which will consequently improve children’s English vocabulary. This finding confirmed the hypothesized mechanism proposed by Matthes and Stoeger (2018) and Hong et al. (1999) that the parental mindset affects their other beliefs and influences their parenting behaviors, which ultimately contributes to children’s academic performance. It is also consistent with Justice et al. (2020) who suggested that parental values toward children’s academic performance could shape the effects of parental mindsets on children’s achievement.

The result that the parental growth mindset about intelligence related to children’s L2 acquisition through the value of importance placed on English and home literacy practices is even more exciting when we consider another finding that SES and the parental growth mindset were not related. This demonstrates that this psychological factor, the parental mindset, influenced children’s literacy development independent of SES, underlining the cruciality and potentiality of a mindset buffering the word gap in children’s L1 and L2 and alleviating educational inequalities. Claro et al. (2016) reported that the academic performance of students with a growth mindset in the lowest 10th percentile of family income was comparable to students from the 80th income percentile with a fixed mindset. Building upon this, the current study reveals the impact of a parental mindset on children’s language acquisition, suggesting the possibility of intervening in L1 and L2 word gaps at an earlier stage of childhood development. This insight opens avenues for early interventions to address language disparities, as advocated by previous researchers (e.g., Andersen & Nielsen, 2016; Rowe & Leech, 2019).

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the relationship between the parental mindset about intelligence and children’s L1 and L2 vocabulary. The major finding is that the parental mindset about intelligence has no direct effects on children’s Chinese and English vocabulary. However, it does have indirect effects on children’s English vocabulary via the parental value of English and home literacy practices in English. This underscores the capacity for parental beliefs to shape children’s proficiency in English as a second language, contingent upon the optimal milieu of parent–child interactions and a literacy-rich home environment. In addition, the parental mindset about intelligence can influence children’s English vocabulary independent of SES. Building on these two major findings, this study offers new evidence of the mindset’s role in addressing reading–income gaps in language learning. These findings resonate with the scholarly discourse initiated by Butler (2019), underscoring the imperative for a further exploration of noncognitive determinants in Second Language Acquisition (SLA) research.

5.1. Implications

The construct of a mindset is dynamic and susceptible to change. Evidence has indicated that mindset alterations can occur swiftly and effortlessly (Dweck, 2006), which can serve as an essential component in educational practices and interventions for children as well as their parents. As this study has shown regarding the effects of a parental mindset on children’s English vocabulary, we have reason to believe that if we carry out more interventions on parents, it may temper the educational inequality caused by SES in children’s English vocabulary. In addition, this study underscores that merely instilling parents with a growth mindset is insufficient. Future interventions should not only focus on cultivating this mindset but also provide actionable guidance to enhance both the quality and quantity of home literacy practices. Against the backdrop of China’s historical emphasis on exam-oriented education, researchers could enlighten parents about the critical role of children’s emergent literacy skills in shaping their future academic achievements. By fostering a growth mindset towards language acquisition and motivating parents from low SES backgrounds to engage in supportive practices, a more holistic approach to parental interventions can be envisioned.

Furthermore, changing parental mindsets yields positive repercussions on children’s mindsets. While a growth mindset can be instilled through explicit interventions, it can also be nurtured via implicit parent–child interactions (Lou & Noels, 2020). Parents with a growth mindset tend to praise children’s efforts. Kamins and Dweck (1999) testified to the transformative effects of positive feedback on children’s mindset, which subsequently impacted children’s success in later academic performance (Mueller & Dweck, 1998). Interventions that provide directive guidance on growth mindset-related practices for parents can tacitly shape children’s mindsets, which will generate inner motivation for children’s language learning. Lastly, this study adds to the literature about the parental general mindset’s influences on children’s L1 and L2 acquisition. Relating mindset to a vital motivational factor, the parental value of English, contributes to the present literature about the effects of task values.

5.2. Limitations and Future Study

Admittedly, this study has several limitations; more future work on this topic is required. First, the questionnaire used the parental mindset about general intelligence rather than a specific language mindset. Parents may have different insights on the malleability of their children’s intelligence and language ability, which could in turn change the results. Nevertheless, Muenks et al. (2015) have testified that it was what parents thought of their children’s intelligence (i.e., a child-specific mindset) rather than what they thought of a domain (i.e., a domain-specific mindset) that made a better predictor. Therefore, this study’s results were also valid. Nonetheless, additional empirical inquiries into the predictive power of specific language mindsets on language outcomes are warranted. Furthermore, seeing as language acquisition consists of many aspects such as listening, speaking, and literacy, more nuanced research about the mindset of different language skills should also be carried out (Mercer & Ryan, 2009). Future research should design more specific language mindset measurements in accordance with the research purposes and identify different effects of various language mindsets.

Second, this study did not include other parental beliefs in L1 acquisition, for example, the importance of child-directed speech and the parental role in building a facilitative home literacy environment; we were not able to examine how parental mindsets interact with other beliefs to influence children’s L1 vocabulary acquisition. Third, the home literacy environment was measured through the parents’ questionnaire, which simplified the complexity of such an environment. Direct observations would help capture more details of home literacy practice and the dynamic nature of literacy-related interactions at home.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.L. and J.Z.; methodology, H.L.; formal analysis, J.L.; investigation, H.L.; resources, J.Z.; data curation, J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, H.L. and J.L.; writing—review and editing, J.Z.; visualization, J.L.; supervision, J.Z.; project administration, J.Z.; funding acquisition, J.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities [24wkjc05].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethics Committee or Institutional Review Board approval was not required for this study at our institution because the research involved minimal risks to participants. The study included parents filling out a questionnaire about their home literacy environment and children being assessed on a few literacy-related measures. We ensured that: Participation was entirely voluntary. Parents signed informed consent forms before participating. Data reporting was conducted anonymously to maintain confidentiality.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in FigShare at 10.6084/m9.figshare.28414175.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Andersen, S. C., & Nielsen, H. S. (2016). Reading intervention with a growth mindset approach improves children’s skills. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(43), 12111–12113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, B., & Wang, J. (2020). The role of growth mindset, self-efficacy and intrinsic value in self-regulated learning and English language learning achievements. Language Teaching Research, 27(1), 207–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, K., & Graddol, D. (2012). English in China today. English Today, 28(3), 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, Y. G. (2015). Parental factors in children’s motivation for learning English: A case in China. Research Papers in Education, 30(2), 164–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, Y. G. (2019). Linking noncognitive factors back to second language learning: New theoretical directions. System, 86, 102127–102131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S., Zhao, J., De Ruiter, L., Zhou, J., & Huang, J. (2020). A burden or a boost: The impact of early childhood English learning experience on lower elementary English and Chinese achievement. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 25(4), 1212–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claro, S., Paunesku, D., & Dweck, C. S. (2016). Growth mindset tempers the effects of poverty on academic achievement. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(31), 8664–8668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coddington, C. H., Mistry, R. S., & Bailey, A. L. (2014). Socioeconomic status and receptive vocabulary development: Replication of the parental investment model with Chilean preschoolers and their families. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 29(4), 538–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, T., & Cromley, J. G. (2014). Changes in implicit theories of ability in biology and dropout from STEM majors: A latent growth curve approach. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 39, 233–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, C. I., & Dweck, C. S. (1978). An analysis of learned helplessness: Continuous changes in performance, strategy, and achievement cognitions following failure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 36, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, L. M., & Dunn, D. M. (2007). The Peabody picture vocabulary test (5th ed.). NCS Pearson, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Durik, A. M., Vida, M., & Eccles, J. S. (2005). Task values and ability beliefs as predictors of high school literacy choices: A developmental analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98, 382–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C. S. (1999). Self-theories: Their role in motivation, personality and development. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House. [Google Scholar]

- Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95, 256–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dweck, C. S., & Master, A. (2008). Self-theories motivate self-regulated learning. In D. H. Schunk, & B. J. Zimmerman (Eds.), Motivation and self-regulated learning: Theory, research, and applications (pp. 31–51). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Eccles, J., Wigfield, A., Harold, R. D., & Blumenfeld, P. (1993). Age and gender differences in children’s self-and task perceptions during elementary school. Child Development, 64, 830–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eren, A., & Raktatiğlu-Söylemez, A. (2020). Language mindsets, perceived instrumentality, engagement and graded performance in English as a foreign language student. Language Teaching Research, 27(3), 544–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frey, B. (2018). The SAGE encyclopedia of educational research, measurement, and evaluation (Volume 1–4). SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, E. A., & Morrison, F. J. (1997). The unique contribution of home literacy environment to differences in early literacy skills. Early Child Development and Care, 127, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grolnick, W. S. (2003). The psychology of parental control: How well-meant parenting backfires. Erlbaum. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haimovitz, K., & Dweck, C. S. (2017). The origins of children’s growth and fixed mindsets: New research and a new proposal. Child Development, 88, 1849–1859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, B., & Risley, T. R. (1995). Meaningful differences in the everyday experiences of young American children. Brookes. [Google Scholar]

- Holden, L. R., & Goldstein, B. (2024). Brief mindset intervention changes attitudes but does not improve working memory capacity or standardized test performance. Education Sciences, 14(3), 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y., Chiu, C., Dweck, C. S., Lin, D. M.-S., & Wan, W. (1999). Implicit theories, attributions, and coping: A meaning system approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 588–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hood, M., Conlon, E., & Andrews, G. (2008). Preschool home literacy practices and children’s literacy development: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100(2), 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Justice, L. M., Purtell, K. M., Bleses, D., & Cho, S. (2020). Parents’ growth mindsets and home-learning activities: A cross-cultural comparison of Danish and US parents. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamins, M. L., & Dweck, C. S. (1999). Person versus process praise and criticism: Implications for contingent self-worth and coping. Developmental Psychology, 35, 835–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khajavy, G. H., Pourtahmasb, F., & Li, C. (2021). Examining the domain-specificity of language mindset: A case of L2 reading comprehension. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 16(3), 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, J., Ji, X. R., Joshi, R. M., & Zhao, J. (2024). Investigating parental beliefs and home literacy environment on Chinese kindergarteners’ English literacy and language skills. Early Childhood Education Journal, 52(1), 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurell, J., Gholami, K., Tirri, K., & Hakkarainen, K. (2022). How mindsets, academic performance, and gender predict Finnish students’ educational aspirations. Education Sciences, 12(11), 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leys, C., Ley, C., Klein, O., Bernard, P., & Licata, L. (2013). Detecting outliers: Do not use standard deviation around the mean, use absolute deviation around the median. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49(4), 764–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyva, D., Yeomans-Maldonado, G., Weiland, C., & Shapiro, A. (2024). Latino home learning opportunities, parental growth mindset, and child academic skills. Early Education and Development, 35(6), 1141–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G., Zhen, F., Lin, Z., & Gunderson, L. (2023). Bilingual home literacy experiences and early biliteracy development among Chinese–Canadian first graders. Education Sciences, 13(8), 808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, E. K. (2019). What we know about expectancy-value theory, and how it helps to design a sustained motivating learning environment. System, 86, 102119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, N. M., & Noels, K. A. (2019). Promoting growth in foreign and second language education: A research agenda for mindsets in language learning and teaching. System, 86, 102126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, N. M., & Noels, K. A. (2020). “Does my teacher believe I can improve?”: The role of meta-lay theories in ESL learners’ mindsets and need satisfaction. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthes, B., & Stoeger, H. (2018). Influence of parents’ implicit theories about ability on parents’ learning-related behaviors, children’s implicit theories, and children’s academic achievement. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 54, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercer, S., & Ryan, S. (2009). A mindset for EFL: Learners’ beliefs about the role of natural talent. ELT Journal, 64(4), 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miele, D. B., Son, L. K., & Metcalfe, J. (2013). Children’s naive theories of intelligence influence their metacognitive judgments. Child Development, 84, 1879–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorman, E. A., & Pomerantz, E. M. (2010). Ability mindsets influence the quality of mothers’ involvement in children’s learning: An experimental investigation. Developmental Psychology, 46(5), 1354–1362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moser, J. S., Schroder, H. S., Heeter, C., Moran, T. P., & Lee, Y.-H. (2011). Mind your errors: Evidence for a neural mechanism linking growth mind-set to adaptive posterror adjustments. Psychological Science, 22, 1484–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, C. M., & Dweck, C. S. (1998). Praise for intelligence can undermine children’s motivation and performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muenks, K., Miele, D. B., Ramani, G. B., Stapleton, L. M., & Rowe, M. L. (2015). Parental beliefs about the fixedness of ability. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 41, 78–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2017). Mplus user’s guide (8th ed.). Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, D. J., & Lin, D. (2023). Cognitive–linguistic skills explain Chinese reading comprehension within and beyond the Simple View of Reading in Hong Kong kindergarteners. Language Learning, 73(1), 126–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, J. E., Adler, T., & Meece, J. L. (1984). Sex differences in achievement: A test of alternate theories. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46, 26–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penderi, E., Karousou, A., & Papanastasatou, I. (2023). A multidimensional–multilevel approach to literacy-related parental involvement and its effects on preschool children’s literacy competences: A sociopedagogical perspective. Education Sciences, 13(12), 1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimer, D., Smith, E., Andersen, I. G., & Sortkær, B. (2021). What happens when schools shut down? Investigating inequality in students’ reading behavior during COVID-19 in Denmark. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 71, 100568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, M. L., & Leech, K. A. (2019). A parent intervention with a growth mindset approach improves children’s early gesture and vocabulary development. Developmental Science, 22(4), e12792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, M. L., & Snow, C. E. (2020). Analyzing input quality along three dimensions: Interactive, linguistic, and conceptual. Journal of Child Language, 47(1), 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sang, B., & Miao, X.-C. (1990). 皮博迪图片词汇测验修订版(PPVT-R)上海市区试用常模的修订 [Revision of Peabody’s revised picture vocabulary test (PPVT-R) trial norm in Shanghai urban area]. 心理科学通讯 [Psychological Science Letters], 5, 22–27. [Google Scholar]

- Sénéchal, M., & LeFevre, J. A. (2014). Continuity and change in the home literacy environment as predictors of growth in vocabulary and reading. Child Development, 85(4), 1552–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shenzhen Statistics Bureau. (2020). Shenzhen statistical yearbook 2020. China Statistics Press. Available online: https://tjj.sz.gov.cn/attachment/1/1382/1382787/8386382.pdf (accessed on 12 February 2021).

- Simpkins, S. D., Fredricks, J. A., & Eccles, J. S. (2012). Charting the Eccles’ expectancy value model from mothers’ beliefs in childhood to youths’ activities in adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 48, 1019–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohr-Preston, S. L., Scaramella, L. V., Martin, M. J., Neppl, T. K., Ontai, L., & Conger, R. (2013). Parental socioeconomic status, communication, and children’s vocabulary development: A third-generation test of the family investment model. Child Development, 84(3), 1046–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y., Barger, M. M., & Bub, K. L. (2022). The association between parents’ growth mindset and children’s persistence and academic skills. Frontiers in Education, 6, 791652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, M., Li, P., Zhou, W., & Shu, H. (2021). Effects of socioeconomic status in predicting reading outcomes for children: The mediation of spoken language network. Brain and Cognition, 147, 105655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H., Steinkrauss, R., Tendeiro, J., & De Bot, K. (2016). Individual differences in very young children’s English acquisition in China: Internal and external factors. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 19(3), 550–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoman, D. B., Sansone, C., Robinson, J. A., & Helm, J. L. (2020). Implicit theories of interest regulation. Motivation Science, 6(4), 321–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, M. R., Buckley, K., Krachman, S. B., & Bookman, N. (2018). Development and implementation of student social-emotional surveys in the CORE Districts. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 55, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westeren, I., Halberg, A. M., Ledesma, H. M., Wold, A. H., & Oppedal, B. (2018). Effects of mother’s and father’s education level and age at migration on children’s bilingual vocabulary. Applied Psycholinguistics, 39(5), 811–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2000). Expectancy-value theory of achievement motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y., & Yang, Y. (2019). RMSEA, CFI, and TLI in structural equation modeling with ordered categorical data: The story they tell depends on the estimation methods. Behavior Research Methods, 51(1), 409–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeager, D. S., & Dweck, C. S. (2012). Mindsets that promote resilience: When students believe that personal characteristics can be developed. Educational Psychologist, 47, 302–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., Liu, Y., & Cheong, C. M. (2024). The effect of growth mindset on motivation and strategy use in Hong Kong students’ integrated writing performance. European Journal of Psychology of Education. Advanced online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J., & Dixon, L. Q. (2024). Bilingual language development. In J. B. Gleason, & N. B. Ratner (Eds.), The Development of Language (0th ed., pp. 369–394). Plural. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).