Abstract

The study on which the article is based investigates which learning strategies multilingual pupils use when using a multimedia and multilingual media offer in geography lessons and how these influence their subject-related learning success. By way of introduction, the potential of multilingualism for geography lessons is presented theoretically and with reference to neurobiology. A multimedia and multilingual learning platform was developed for the study and trialled in geography lessons. The pupils’ usage strategies were recorded using screen recordings and sound-thinking protocols and mapped in a differentiated way in a model. The most common usage strategies that can be observed include “reversion”, i.e., processing the same information medium first in one language and then again in another, the use of reading strategies, multilingual notetaking, the use of image and map information, bundling information and structured summarising. These utilisation strategies show a positive influence on learning outcomes.

1. Introduction

Statistics show that around 25% of pupils in Germany speak at least one other language when they start school (Blossfeld, 2016, p. 147). The proportion of children with a migrant background at general education and vocational schools was 39% in 2021 (Mediendienst Integration, 2024). Children and young people with a migrant background often grow up bilingual or multilingual, without multilingualism and a migrant background necessarily being congruent (Ritterfeld et al., 2013, p. 1). The targeted use of multilingualism has been a relevant topic for foreign language didactics in English and French since the 1990s (Thormann, 1994, p. 175; Niekamp & Hu, 2001, p. 239), but also for psychology, educational science, mathematics and the natural sciences (Androutsopoulos, 2018, pp. 193–195; Coulmas, 2017, p. 41). This leads to the theoretical demand for interdisciplinary collaboration between subjects in language education. This could be based on the “language across the curriculum approach”, which calls for a (greater) appreciation and promotion of all languages spoken by pupils at school (Weissenburg, 2013, p. 31).

Approaches with a language-sensitive and multilingual focus are also increasingly being developed in geography didactics (Budke & Kuckuck, 2017, pp. 7–37; Morawski & Budke, 2017, pp. 61–84; Maier & Budke, 2018, pp. 36–49). Impulses were provided by educational science and linguistics, among others, which already referred to the ethnic and linguistic diversity of pupils (Dirim et al., 2008, pp. 9–19) in the context of intercultural pedagogy in the 1990s and profiled the concept of “life-world multilingualism” in the debate (Gogolin, 1988, p. 10).

There is a significant research gap for the subject of geography in the conceptualisation of multilingualism and its methodological and didactic application in school lessons (Hofer & Jessner, 2019, p. 1). Geography lessons are particularly suitable for multilingual teaching practice due to their globally orientated content. The multicultural and multilingual background of pupils should be actively integrated into the teaching and learning environment (Weissenburg, 2016, pp. 33–49; Repplinger & Budke, 2018, pp. 171–177). In school practice, German dominates as the language of instruction, which means that pupils’ “family languages” (Riehl, 2018, p. 36) have so far hardly been used and learning potentials have not been tapped (Repplinger & Budke, 2018, p. 166). Modern research approaches define pupils’ multilingualism not as an obstacle to learning but as a resource (Haberzettl, 2016, pp. 62–77; Riehl, 2018, p. 19).

This article presents the results of a research project on the use of multilingual and digital media in geography lessons. In a pre-post design, students’ use of a multilingual and digital learning platform in geography lessons in the eighth grade of a German grammar school was investigated and evaluated. The study focuses on the targeted use of multilingualism to develop subject-specific skills and examines the strategies of multilingual students when using the material. Two research questions guide the practical research interest:

- What learning strategies do pupils use when working with multilingual teaching materials?

- Which of these learning strategies are particularly successful for subject-related learning?

Firstly, the international state of research on the topic is presented. This is followed by the methodological considerations for the study, the results and the discussion.

2. Theoretical Background

Multilingualism extends across diverse social contexts and includes not only the knowledge of several languages but also the flexible use of these languages in different communicative situations (Grosjean, 2010, pp. 4–5). This theoretical perspective differs from pure bilingualism and emphasises the dynamic interactions between the languages.

In a narrower sense, multilingualism is defined as the ability to speak and write at least three languages, with external multilingualism encompassing the ability to speak several standard languages and internal multilingualism encompassing the ability to speak linguistic variants (Földes & Roelcke, 2022, p. 17; Riehl, 2014, pp. 16–17). These facets take into account lived language practice at individual and social levels and illustrate the complexity of the concept. It should be noted that equivalent competence in several languages at the level of native speakers of the first language is the exception rather than the rule (Cook & Singleton, 2014, p. 3).

The importance of multilingualism goes beyond an individual’s cognitive flexibility and problem-solving skills (Bialystok, 2017, p. 98). The importance of multilingualism goes beyond an individual’s cognitive flexibility and problem-solving skills (Bialystok, 2017, p. 98).

In an increasingly globalised economy, the ability to be multilingual offers significant strategic advantages. Multilingual employees facilitate communication in international teams, which is crucial for the success of multinational companies. Effective communication helps to minimise misunderstandings and encourages collaboration (Lauring & Selmer, 2012, pp. 262–263). This is particularly important in projects that require cultural sensitivity and precise communication. Multilingualism also improves access to global markets. Companies with multilingual employees can better respond to the needs and expectations of different customer groups and take cultural nuances into account. This leads to an improved market position and increased competitiveness (Lauring & Selmer, 2012, p. 264).

Companies are increasingly recognising the value of multilingual employees, particularly in terms of innovation and competitiveness. Multilingual employees bring a diversity of perspectives and ideas that can foster creative problem solving and innovation. This diversity of thought is a significant advantage in today’s fast-paced and dynamic business world (Lauring & Selmer, 2012, p. 265).

Multilingualism is thus seen not only as an individual ability but also as a social phenomenon that promotes cultural diversity and facilitates interaction between different linguistic communities (Grosjean, 2010, p. 15; Grosjean, 2020, pp. 428–448). This comprehensive view requires an interdisciplinary approach that incorporates linguistic, cognitive and socio-cultural aspects.

The theoretical and methodological conceptualisation of multilingualism in school learning groups ensures its efficient use in the classroom, with multilingual teaching and learning settings aimed at promoting subject-specific skills and taking social diversity into account (Viebrock, 2019, p. 219; Coulmas, 2017, pp. 27–59; Hofer & Jessner, 2019, p. 11).

Only a theoretical and methodological conceptualisation that takes into account the linguistic diversity of school learning groups guarantees the efficient use of multilingualism in the classroom. Multilingual teaching–learning settings are geared towards the development of subject-specific competences and the multilingual social construction of diversity and, thus, meeting the potential requirements of dynamically developing social practices.

2.1. Student Teachers’ Experiences with the Integration of Multilingualism in the Real World

The experiences and wishes of student teachers with regard to multilingual methods were analysed in a quantitative online survey. The starting point for the authors’ question was the integration of “didaktisch-methodische Handlungsleitlinien […], die sich damit befassen, wie genau das gesamte sprachliche Repertoire Mehrsprachiger produktiv in Lehr-/Lernkontexte einbezogen [werden können]” (Goltsev & Olfert, 2023, p. 212). The results show that students have little experience of multilingual methods and few opportunities to use them actively. A recent meta-study on student teachers’ attitudes towards multilingualism evaluates five empirical studies from four European countries with the aim of optimising the survey parameters so that respondents “express their beliefs more genuinely” (Lundberg & Brandt, 2023, p. 7). The findings suggest that the research adopts a Eurocentric perspective in relation to multilingualism and multilingualism. A change in perspective is suggested “to include an assessment of teachers’ beliefs about monolingual students’ (language-related) learning difficulties and an examination of multilinguals’ perspectives on monolingualism” (Lundberg & Brandt, 2023, p. 7).

A study conducted in Germany, in a pre-post study design, shows that participation in a compulsory module on multilingualism changes the attitudes of prospective teachers to the effect that multilingualism can be used in the classroom. However, the implementation of multilingualism in practice is seen as difficult by the study participants (Lundberg & Brandt, 2023, p. 5; Schrödler et al., 2023, p. 11). A qualitative interview study with primary school teachers clearly shows the practical limits of implementing multilingualism depending on the teachers’ attitudes. Although the teachers interviewed can imagine multilingual teaching, this is only possible in selected subjects and under the control of the teachers (Lange et al., 2023, pp. 103, 115). The question of the multimedia preparation of teaching materials is discussed in the context of German lessons using web-based multilingual book portals. The results show that these are mainly “parallel multilingual print offers” (Dube et al., 2023, p. 161) that provide information in only two languages. However, this must be criticised, as binary language offerings do not adequately represent the diversity and nuances of multilingualism. In particular, Keimerl et al. (2023, p. 242) highlight tasks related to productive multilingualism as a crucial desideratum for cooperation between different disciplines. Although the authors refer to modern foreign languages and improving the professional skills of student teachers, the diagnosis of multilingualism, which is located in the actual subject disciplines, highlights the desideratum for subjects that are not explicitly concerned with language acquisition in a particular way. The analysis of current studies and thematic articles highlights the need for action at different levels. Even experienced teachers are often unaware of the potential of multilingualism for teaching (Georgi, 2011, pp. 265–269). A study with qualitative guided interviews showed that multilingual student teachers in particular often have a negative attitude towards the use of multilingualism in the classroom, which can be explained by their educational biography (Budke & Maier, 2019, pp. 37–38). The targeted use of multilingual teaching units or methods is rare in German subject teaching (Bredthauer, 2019, pp. 127–143).

Recent studies clearly show that primary school teachers consider multilingualism to be important for their professional practice and are positive about the practical implementation of multilingualism in the form of prepared tasks for the children (Lange et al., 2023, p. 103). Multilingual teaching and materials are particularly important for refugee pupils. They often arrive in the German education system with little knowledge of German and have to attend regular monolingual classes after a short time (Böttjer & Plöger, 2023, p. 51). This school practice was evaluated in two ethnographic studies and confirms the already known pattern of “German commandments and language prohibitions” (Böttjer & Plöger, 2023, p. 55).

2.2. Importance of Multilingualism in the Classroom and Later in Life

Multilingualism continues to be seen as an obstacle to integration, even though many pupils at German schools are multilingual (Hinnenkamp, 2010, p. 27f.). For decades, the deficit hypothesis regarding the multilingualism of migrant woman has been propagated in research and public discourse (Becker-Mrotzek & Roth, 2017, p. 26). On the other hand, neurobiological studies show that bilingual children require less brain capacity to utilise linguistic resources than children who grow up monolingual and only learn a second language at secondary school from the age of 10 (Franceschini, 2014, p. 212).

In terms of grammatical correctness and learning other languages, multilingual children are superior to monolingual children. Multilinguals also show superiority in recognising linguistic patterns in words and sentences, i.e., in meta-linguistic skills and linguistic flexibility (cf. Baechler, 2015, pp. 124–130), which has a positive effect on reading skills (Riehl, 2006, p. 19). The positive consequences of this are also confidence in strategies such as paraphrasing, codeswitching and foreignising (adapting a word to supposed rules of the target language) (Riehl, 2006, p. 19). By strengthening neural networks, the areas of the brain where language and object processing take place are particularly targeted (Brem & Maurer, 2018, p. 130), which facilitates the acquisition of specialised content (Hayakawa & Marian, 2019, p. 24). The use of multilingual language skills (both written and oral) makes it easier for students and teachers to use a wider range of linguistic terms and phrases, as well as increasing the opportunities for barrier-free interaction when teaching topics that are not only geographical.

Heuzeroth and Budke (2020, p. 31) have shown that multilingual geography teaching is beneficial for the formulation of causal relationships. Self-directed learning and knowledge acquisition can be encouraged and facilitated by, among other things, the use of multilingual digital teaching materials (Repplinger & Budke, 2022, pp. 150–158).

The European Union advocates that European citizens should have a high level of linguistic competence in at least three languages (European Union, 2020, n.p.), demonstrating that multilingualism is now positively valued due to migration movements and globalisation.

2.3. Learning Strategies as Central to Educational and Teaching Research

The question of effective learning strategies is of central importance for educational research and pedagogical practice. Foreign language didactics, which argues on the basis of multilingualism, uses the term “learning strategies” (Würffel, 2006, p. 83) and develops a basic model for conceptualising a specific typology of learning strategies. This subsumes various procedures that represent cognitive or metacognitive actions that learners use consciously or unconsciously to influence the acquisition of knowledge, master learning tasks and thus achieve the learning goal (Würffel, 2006, p. 72). However, the term is blurred in that “learning strategies” are defined and used in different contexts in academic discourse, so that the content is determined by the context of use itself (Mandl & Friedrich, 2006, pp. 3–25). The importance of learning strategies, in particular steering strategies, control strategies and understanding strategies, for the learning process is well documented in the academic literature, as will be shown below.

2.3.1. Steering Strategies

Steering strategies relate to the planning and organisation of the learning process. They help learners to set their learning goals and find efficient ways to achieve them. The literature shows that setting clear learning goals and creating learning plans can increase the effectiveness of learning (Zimmerman, 2008, p. 166). The conscious setting of priorities and the allocation of learning time are also important aspects of control strategies (Pintrich & De Groot, 1990, p. 33).

2.3.2. Control Strategies

Control strategies include activities that serve to monitor and adjust learning progress. This includes the ability to assess the quality of one’s own learning and make adjustments where necessary. Research has shown that regularly reviewing one’s knowledge, for example, by self-testing or summarising, can help to improve understanding and retention of information (Dunlosky et al., 2013, p. 4). The use of metacognition, i.e., awareness of one’s own thought processes, is an essential component of effective control strategies (Flavell, 1976, p. 231; Gebele et al., 2022, p. 951).

2.3.3. Understanding Strategies

Understanding strategies provide learners with tools to develop a deeper understanding of learning content. One of the basic techniques is to create mental models that allow information to be put into a meaningful context. These mental models serve as cognitive structures that facilitate the organisation and interpretation of information (Pressley, 1982, pp. 296–309). Asking questions is another effective comprehension strategy. By asking specific questions about the learning content, learners promote deep understanding as they are encouraged to think about the information and make connections between different concepts (King, 1994, pp. 338–368).

These strategies help learners to learn more efficiently, deepen their knowledge and develop metacognitive skills. Educators and educational researchers should be aware of these findings and incorporate them into the design of curricula and learning environments in order to achieve optimal learning outcomes. The promotion of learning strategies can thus make a decisive contribution to improving education and learning success.

The study presented here investigates the extent to which the strategies presented are actually used by students when processing multilingual teaching material and thus closes an existing research gap.

3. Methodological Approach

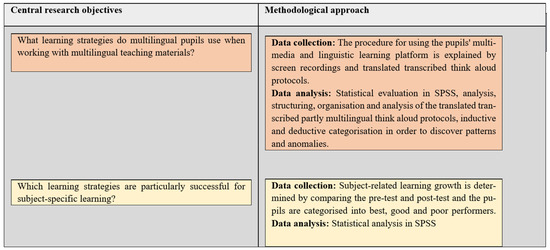

As part of the study, pupils were given the opportunity to use a multilingual digital learning platform (https://www.multilinguale-rheinexkursion.uni-koeln.de/joomla/index.php/de/, accessed on 5 December 2024) in geography class. Figure 1 visualises the central research objectives and the methodological approach. A central research interest of the study is to identify and document the learning strategies used by the students independently.

Figure 1.

Central research questions and methodological approach.

3.1. Carrying out the Data Collection

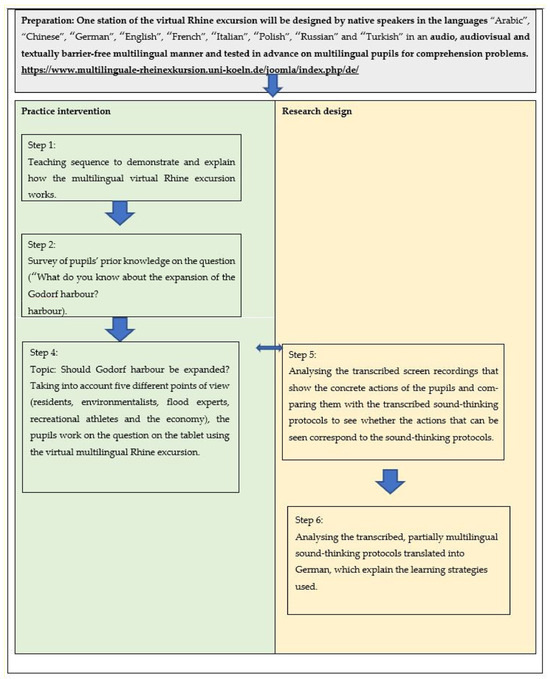

The data were collected by analysing a questionnaire on the main content of the unit (a conflict over the use of land for the expansion of a harbour in Cologne was discussed), screen recordings of the pupils working on the multilingual learning unit and translated, transcribed sound-thinking protocols illustrating the pupils’ actions when working with the unit. The following figure (Figure 2) visualises the different steps of the study.

Figure 2.

Overview of the procedure in the practical intervention.

3.2. Test Subjects

The test group consists of 25 German pupils in year 8 of a grammar school in Düsseldorf (NRW, Germany), of whom 7 are female and 18 are male. The average age is 13 years. A total of 17 out of 25 pupils come from families that are not originally of German origin and therefore have a migration background. The following definition is used: “A person has a migration background if they or at least one of their parents were not born with German citizenship” (BAMF, 2020). In the group of pupils, 69% have a migrant background. This figure is well above the average of 39,4 per cent at grammar schools in the federal state of North Rhine-Westphalia for the 2020/21 school year (Landesbetrieb IT.NRW Statistik und IT-Dienstleistungen, n.d.). The most frequently mentioned non-German family languages is Turkish, closely followed by Arabic and Russian.

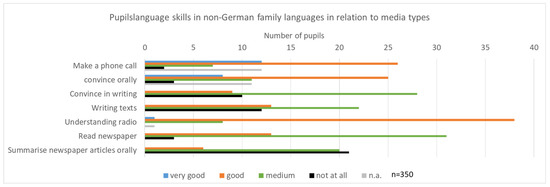

3.3. Language Skills—Survey and C-Test

In order to determine the pupils’ knowledge of the respective family languages and of German as the language of instruction, which might influence the strategies chosen, a survey of the respective language skills was carried out. In the test group, language skills in the respective non-German family language(s) were assessed by means of a questionnaire, and German language skills were assessed by means of a C-test. The C-test was carried out according to the scheme of Baur et al. (2013). The data serve as independent variables that can possibly explain the usage behaviour of multilingual teaching materials. The questionnaire was used to determine the following combinations of home languages with English as a foreign language at school (number of students in brackets): Turkish (13), Turkish/Kurdish (1), Arabic (4), Russian (3), Tamil & Persian (1), Serbian (1), French (1) and Italian (1). The 25 pupils answered questions about their language skills in their respective family languages in seven pre-defined categories, distinguishing between oral and written skills. Some of the pupils have three or four family languages. The pupils ticked boxes to indicate how well they could ‘make a telephone call’, ‘understand a radio report’, ‘read a newspaper’, ‘persuade orally’, ‘summarise orally a newspaper article’, ‘persuade in writing’ and ‘write texts’ in their respective non-English family language(s) (see Figure 3). Pupils are also asked to rate their language competence(s) in seven categories on a Linkert scale. The scale defines the categories “very good”, “good”, “average”, “not at all” and “no answer” as possible classification options.

Figure 3.

Language skills of pupils in their non-German family languages in relation to media types.

Adding up the pupils’ answers to their respective language skills in their three or four family languages gives n = 350 answers. As some pupils have more than one family language, there may be more than the original number of students (25) in one category. The distribution of the 350 responses across the 7 categories is shown in Figure 3.

Written competence in the non-German family language is, in the majority of cases, rated as weaker than oral competence; reading comprehension of the newspaper is also only rated as “average”, and oral summarising of what has been read is largely excluded (“not at all”) (see Figure 3).

Another test, the C-test, was used to assess the pupils’ knowledge of German. The test consists of five short texts in which words or parts of words are omitted or distorted. The students had to correct the incorrect passages (Baur et al., 2013). All but one of the students in the test group scored over 90% of the possible points, with nine pupils scoring 100%. This shows that almost all of the pupils in the study had very good German language skills and were able to understand the German materials on the learning platform.

3.4. Pre-Test of Content Knowledge

Before the pupils work with the multilingual learning platform, a content knowledge test is carried out. The aim of this pre-test is to find out what prior knowledge the pupils have about the topic to be taught.

In the first part of the knowledge test, the pupils are asked to draw the location of the Godorf harbour in Cologne on a map, on which only the Rhine is marked as a river, and to describe the location of the Godorf harbour in a text.

In the second part of the prior knowledge questionnaire, the pupils are asked to describe what they know about the topic of the unit, the planned expansion of the harbour and the social discussions and effects associated with it. The evaluation of the pre-test shows that none of the pupils can locate the harbour of Godorf on the map and that they have no prior knowledge about the social debate and the effects of the planned harbour expansion.

3.5. Determining the Increase in Knowledge Through a Post-Test

At the end of the teaching experiment in the form of a six-hour series of lessons, a final test, a post-test, is carried out. In the post-test, the pupils fill in a structured questionnaire with open response categories on the following topics: description and location of the harbour of Godorf, description of conflicts and actors, and effects. The answers will be checked against a set of expectations and the pupils will be awarded points. On the basis of the points obtained, the pupils are divided into three different ability groups, which is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Presentation of three groups of pupils according to the post-test result in relation to their topic-related knowledge.

The pupils are consistently successful, achieving 9 to 17 points out of a possible 18.

3.6. Categorisation to Evaluate the Sound Thinking Protocols

Pupils are asked to think aloud as they work on the multilingual learning platform. A qualitative method—the think-aloud protocol—is used to understand why students make decisions for their particular approach and which learning strategies they use.

The think-aloud protocols are recorded simultaneously with the learning process, without pre-determined questions, so that the pupils’ utterances are not steered in a particular direction or predetermined in advance: only “[un]structured think-aloud protocols allow an immediate impression of the decision-making processes” (Konrad, 2010, p. 481). In this way, the influence of standardised questions as well as self-interpretation or reflection by the respondents, which can occur in post festum protocols, is excluded. The specific procedure can be reconstructed for each pupil according to “perceived relevance and/or personal interest” (Würffel, 2006, p. 128). The language used for thinking aloud is left to the respondents. The transcription takes into account colloquial syntactic deformations. For the analysis, the transcribed think-aloud protocols are translated into German.

The translated think-aloud protocols are carefully read, and open codes are created that capture the main themes, patterns and concepts in the data.

3.7. Validation

Intercoder reliability ensures that categorisations are selected correctly. The procedure aims at objectivity by including different subjective points of view (Mayring, 2010, pp. 116–122; Müller-Benedict, 1997, p. 2f.). The intercoder reliability is calculated using kappa (Cohen, 1960, pp. 37–60). A kappa over all 3 rater pairs results in a value of 0.86, which, according to Landis and Koch (1977, p. 159), represents an “almost perfect agreement value” and, according to Monserud and Leemans (1992, pp. 275–293), a “very good value”.

3.8. Deductive Categorisation

Deductive categorisation is based on the scheme of language learning strategies by Chamot et al. (1988, p. 1) and on the analysis of research literature (Nawratil et al., 2009, p. 338). This structured method makes it possible to analyse pupils’ actions when working with the learning platform and to identify control, monitoring and comprehension strategies, cf. Table 2: Exemplary categorisation for the evaluation of the sound-thinking protocols (see Section 2.3).

Table 2.

Exemplary categorisation for the evaluation of the think-aloud protocols. Source: own presentation.

3.9. Inductive Categorisation

In addition to the deductive supercategories, inductive subcategories are formed. These categories are not predetermined, but emerge organically from the data (Mayring, 2010, pp. 116–122).

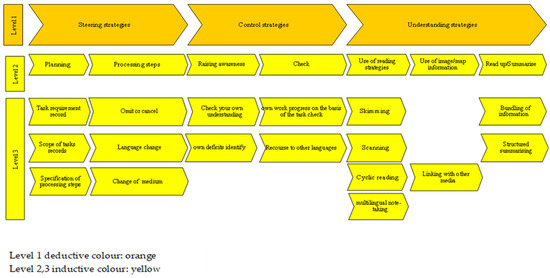

The following categories were created (see Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Model of the most successful multilingual learning strategies. Source: own illustration.

The model of the most successful multilingual learning strategies is divided into three levels (see Figure 4). The three levels are colour coded as deductive (orange) and inductive (yellow).

It shows the multilingual and multidigital learning strategies used by the students.

4. Outcomes

Learning success is largely determined by the use of certain strategies (=procedures) in dealing with the multimedia and linguistic learning platform (=virtual Rhine excursion).

The analysis of the results clearly shows that at least two languages are used by the pupils when using the multimedia and multilingual learning platform. With one exception, all pupils used the multilingual teaching material.

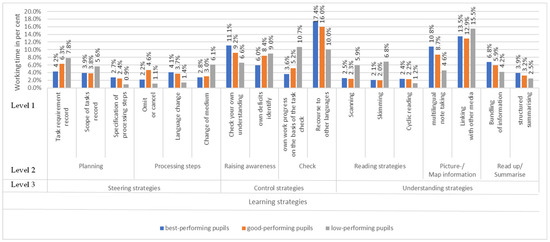

Utilisation Strategies of the Best-Performing, Good-Performing and Low-Performing Pupils

It also shows the differences between the best-, good- and low-performing pupils in terms of their usage strategies. The time spent on the multilingual materials by the three groups is shown as a percentage.

The best-performing pupils are more time-efficient in their use of control strategies, especially in determining processing steps and planning the learning process, than the lowest performing pupils. They are quicker and more accurate in determining how to approach and structure a task and are better able to estimate the amount of work involved than those pupils whose subject learning gains after working with the material are lower. This obviously enables them to use their time more efficiently and to concentrate on the essentials. The best-performing pupils rely more than the low-performing pupils on targeted checking strategies, such as regularly checking their own understanding and using other languages, i.e., working on the same material first in one language and then again in a second language to clarify information and ensure that they understand the material correctly (see Figure 5 ‘Checking strategies’). The best-performing pupils are also able to check their understanding critically and identify and correct any weaknesses or gaps in their knowledge. The best-performing pupils use targeted and efficient methods to link information. They often start by using video material to gather information. After watching the videos, they record this information on paper or digitally more often than lower-performing pupils (see Figure 5 ‘Comprehension strategies’).

Figure 5.

Learning strategies of the best, good and low-performing pupils when working with the multimedia multilingual learning platform.

The group of best-performing pupils then reads the texts in the unit, often using understanding strategies such as scanning, skimming and cyclical reading (see Figure 5 ‘understanding strategies’) and making notes, sometimes in several languages, to compare with the information from the videos (Figure 5 ‘understanding strategies’). The first two are quick-reading methods. They are used for orientation without having to go through the entire text to understand it. “Skimming” refers to skimming the text based on headings, graphic highlights or images in order to decide what is worth looking at more closely. “Scanning” refers to the targeted search for desired information (words, data, facts). Intensive reading aims at a comprehensive understanding of the text. In cyclical reading, the methods are linked together: The passages that are subsequently read intensively are determined by skimming (Grünwied, 2017, p. 47). This gives them a comprehensive overview of the topic. On this basis, they compare the information they have gathered again, often with the help of audio material, in order to gain any new insights. The best-performing pupils use some of the information they have gathered in this way (Figure 5 ‘understanding strategies’) to create a diagram that visualises the connections and relationships between the different facts and concepts. Finally, they often apply this structured information to maps and pictures (Figure 5: ‘Strategies for understanding’) in order to understand and clarify spatial relationships and geographical aspects of the topic. This systematic and structured approach to linking information, using reading strategies, multilingual notetaking, linking to other media, synthesising and summarising information in a structured way and applying it to maps and images contributes significantly to their learning.

In contrast, the good-performing pupils are slightly less efficient in their approach to control strategies, spending more time and being less precise in how they approach and structure a task in the best possible way. The high achievers use an even distribution of their working time on control strategies, without dwelling on extremes. The good-performing pupils also use comprehension strategies, but they use them less efficiently than the best-performing pupils. They need slightly more time to achieve the same results. Like the best performers, the good-performing pupils also focus specifically on ‘understanding task requirements’ and ‘understanding task scope’ (see Figure 5 ‘Control strategies’). They are able to understand the requirements but take slightly more time than the best performers.

The low-performing pupils invest more time in analysing tasks within the control strategies as they take longer to understand the scope and requirements of the tasks. The low-achieving pupils invest comparatively more time in ‘identifying their own deficits’ (see Figure 5: ‘Control strategies’) as they need additional support to consolidate their understanding and identify weaknesses. These pupils use less resources to other languages, language change, summarising and multilingual notes when analysing media than the other two groups.

5. Discussion of the Results and Conclusions

The use of multilingual teaching materials in today’s educational world plays a crucial role in the transfer of knowledge and has been shown to influence pupils’ learning success (Clark & Mayer, 2016, p. 102; Moreno, 2004, p. 100). These materials provide teachers with a variety of tools to improve the teaching–learning process by increasing interactivity and learner engagement (Mayer, 2014, p. 65). The results of our study confirm the conclusions of the study by Clark and Mayer (2016) and Moreno (2004). The pupils show great interest in working on the multilingual learning platform, as shown by the screen recordings as well as the thinking aloud protocols. According to Grosjean (2010, pp. 4–5), multilingualism is not only an individual cognitive ability but also a social resource that enables inclusion and access to various learning approaches. Our study shows that a range of methodological skills and strategies are required to work successfully with multilingual materials.

Multimedia and multilingual teaching materials make it possible to present complex concepts in a way that can be better understood and retained (Mayer, 2009, p. 16). Research by Mayer (2001, p. 5) has shown that oral and visual multimedia learning materials can enhance comprehension and absorption of learning content. These materials utilise different sensory channels to convey information and offer students the opportunity to improve cognitive processing of information (Clark & Mayer, 2016, p. 102). The combination of textual, audiovisual and cartographic materials opens up new horizons for subject-related learning. Graphics and images can visualise complex information and help learners to better grasp abstract concepts (Tversky, 2005, p. 223f.). Also, learners can create information graphics or mental maps from text-based or audiodigital media.

The best possible educational success and better learning outcomes can only be achieved by redesigning learning environments and curricula in which teachers teach and practise targeted learning strategies for pupils. Steering strategies, control strategies and comprehension strategies form the basis for the generation of knowledge. Knowledge and confident use of these strategies help pupils to learn more effectively, deepen their knowledge and develop metacognitive skills.

Learning strategies are of great importance for an effective learning process (de Boer et al., 2018; Murayama et al., 2013). The importance of learning strategies, especially steering, control and understanding strategies in the learning process, is well documented in the scientific literature (see Section 2.3).

According to Flavell (1976, p. 231) and Gebele et al. (2022, p. 951), an essential component of effective control strategies is awareness of one’s own thinking processes, i.e., the use of metacognition. Dunlosky et al. (2013, p. 4) and Gebele et al. (2022, p. 951) argue for the importance of control strategies in learning.

Zimmerman (2008, p. 166) shows that learning can be made more effective by setting clear learning goals and plans. Pintrich and De Groot state that it is also important to set priorities and organise learning time (Pintrich & De Groot, 1990, p. 33). Zimmerman and Pintrich and De Groot emphasise the particular importance of control strategies in the learning process. Learning progress needs to be monitored and adjusted through control strategies. Dunlosky et al. (2013, p. 4) state that continuous summarising or self-testing are important steps in checking one’s knowledge and help to ensure that information is better retained and understanding is improved. Our study shows that people need to check their understanding regularly. This is done by using multiple languages, e.g., working through the material first in one language and then again in a second language, which ensures that information is understood correctly and that the whole learning material is understood correctly.

Pressley (1982, pp. 296–309) states that deep understanding of learning content is achieved by teaching mental models (cognitive structures) that facilitate the organisation and interpretation of information. According to King (1994, pp. 338–368), a deeper understanding of learning content is achieved by asking learners specific questions about the learning content, as learners are encouraged to reflect on information and make connections between different concepts. Our research shows that the most successful understanding strategies are multilingual notetaking and bundling of information.

Our study results show, by comparing the strategy use of the best, good and low performers (see Figure 5), that maximum learning success can only be achieved through effective planning and organisation of the learning process (management strategies), consistent monitoring and adjustment of learning progress (control strategies) and other tools that enable a deep understanding of the learning content.

As our study shows, multimedia and multilingual learning materials are particularly suitable for presenting learning material in different languages at the same time. This conceptualisation ties in with pupils’ habits of using internet research on websites with multilingual information options. Multimedia presentation on the internet is a key source of multilingualism because “verschiedenste Formen der Mehrsprachigkeit [ergeben sich] allein durch die Nutzung der neuen Medien” (Mayr, 2020, p. 46). Freedom of choice is psychologically important because it gives pupils sovereignty in the reception of information and thus ensures independence in the entire learning process in the acquisition of subject content (Riehl, 2006, p. 19).

The integration of different languages into the classroom is a central aspect of the multilingual approach and contributes to the promotion of multilingualism (García, 2009, p. 8). This is particularly relevant in schools where pupils speak different family languages. The use of multiple languages in multimedia materials enables learners to develop and strengthen their language competence in different contexts (García, 2009, p. 308). Multilingualism is of great importance in our globalised world and has been widely accepted in society since 2015. “Multilingualism has become the norm in everyday school life. There are hardly any learners who have grown up in a purely monolingual environment” (Mayr, 2020, p. 46). Multilingualism is based on individual characteristics (Hofer & Jessner, 2019, p. 11), the diversity of which must be taken into account in the classroom. A broad range of languages avoids disadvantaging individual group members and stimulates learning ability in teaching–learning settings (Weissenburg, 2013, pp. 23–49).

The empirical results of our study show that a differentiation of the media offered takes into account the different language skills of the learners.

The study by Pintrich and De Groot (1990, p. 38) shows that “pupils who were more cognitively engaged in trying to learn by memorizing, organizing, and transforming classroom material through the use of rehearsal, elaboration, and organizational cognitive strategies performed better than pupils who tended not to use these strategies”. Zimmerman (2008, p. 166) draws a link between metacognitive (self-regulated) learning strategies and improved academic performance. Our study shows that the best performing pupils used steering, control and comprehension strategies differently in the post-test compared to the low performing pupils. The most successful pupils are characterised by the use of steering strategies such as efficient planning and rapid goal setting. In contrast, low-achieving pupils are unable to use steering strategies effectively, as evidenced by their slow comprehension of the task. Steering strategies such as regular self-monitoring and the use of multilingualism are used intensively by the best-performing pupils. The low-performing pupils are characterised by a lack of feedback on the task. Comprehension strategies such as linking media and languages (multilingualism), multilingual notetaking, synthesising information and structured summarising are used by the best-performing pupils. In contrast, low-performing pupils misuse reading strategies and use too many media formats, make much fewer multilingual notes, summarise less and structure less than the best-performing pupils.

Only a small percentage of multilingual pupils have a complete command of the family languages, both orally and in writing. This is shown by the evaluation of the preceding survey of pupils’ self-evaluation of their own language and speaking skills. When using video and audio media in the learning unit, only oral competence in the respective language is required. Reading texts requires written language skills in the family language (Repplinger & Budke, 2018, p. 175). An oral–audio-visual–written offer is multilingual, ‘barrier-free’ and inclusive for pupils. They can decide in which form they want to use which language without any hurdles or disadvantages. The choice option is based on reflection on self-assessment and evaluation of one’s own language skills (Tassinari, 2012, p. 15f.; Schramm, 2010, p. 218), which in turn expands cognitive skills (Oleschko et al., 2016, p. 15).

Based on our findings, we recommend the following procedures to teachers and curriculum designers:

Establishing processing steps, checking the pupils own understanding of content, referring back to other languages, comparison with other languages (language switching), multilingual notetaking as a strategy to be taught to pupils, bundling information, and structured summarising should be anchored in the curriculum.

We recommend the following to teachers when implementing the above methods: the provision of multilingual teaching materials that can be easily switched between different languages, whether in text or audio form; teacher training and methodological training for teachers and pupils on specific teaching examples; the provision of AI software for teachers to overcome language difficulties and to differentiate performance (Bavarian BAYLKI initiative).

AI can be used at short notice as an interpreter for teaching content that is difficult to understand in the official language, or to quickly translate teaching material into a language previously unknown to the teacher. Pupil terminals should include applications that can use AI and augmented reality to translate classroom texts in real time into the pupils’ native language. For educational purposes, artificial intelligence such as Deepl can be used to quickly translate texts.

The proposed implementations should be supported by well-structured worksheets that guide the pupils’ thinking and learning process, e.g., design of the worksheets in a uniform, subject-specific breakdown into main points such as headings, individual and group tasks, additional material, and the possibility to use the material independent of the internet via stick-on QR codes on the tablet or via audio-digital reading pens in the pupils’ mother tongue at different language levels (everyday language or simple language). Multilingual texts can also be made available more easily via QR codes at different levels (everyday language or simple language). However, this requires a nationwide supply of pupil devices and a stable and fast internet connection.

This will make distributing multilingual learning materials much easier for teachers and will make multilingual learning content easier to access for pupils. However, the results of the lessons should be recorded in the official language so that all pupils can understand them.

Despite the valuable insights provided by our study, several limitations must be considered. The sample size of just 25 pupils and the focus on a single class in a secondary school in Germany (North Rhine-Westphalia (NRW)) limit the generalisability of the results to a broader and more diverse pupil population. The regional focus on NRW may have also introduced bias, as local educational policies and language demographics could have influenced the findings. Future research could include a larger and more diverse sample in order to increase the generalisability of the results.

The empirical results of our study show that a differentiation of the media offered accommodates the different language skills of the learners.

The findings confirm a hypothesis of multilingual didactics: it is not only a matter of appreciating the second language or compensating for deficits in German competence, but also of confirming knowledge and metacognitive consolidation (Kaiser & Kaiser, 2018, p. 13f.; Budke, 2012, pp. 3–5). By referring back to the topic in another language, pupils consolidate their knowledge acquisition of the information elements. This reassurance, which has not yet been documented in studies of multilingual didactics, and its systematic nature are linked to very good learning results and determine the qualitative learning progress of the group of the best pupils.

From the results of the study regarding the usage strategies of the best performing pupils, it can be deduced that lesson content must be adapted to the linguistic heterogeneity of the pupils without barriers and that the pupils must also be taught usage strategies and given the opportunity to test and practise usage strategies such as, for example, linking information, referring back to a previously worked topic in another language, using multilingual notetaking and linking with other media. They must also be given the opportunity to test and practise usage strategies such as linking information, including referring back to a previously worked topic in another language, using reading strategies, multilingual notetaking, linking with other media, bundling information and structured summarising as well as using maps and images. These utilisation strategies show a high correlation with very good learning outcomes.

Overall, multilingual and multimedia teaching materials help to make the educational process more effective and efficient, promote learners’ language skills and help them to better understand and retain specialised content. The targeted use of such media in various educational environments is crucial in order to meet the increasing demands on education today and prepare pupils for the challenges of modern society in the best possible way. With regard to the design of geography lessons, we recommend taking into account the heterogeneous language skills of multilingual pupils when planning and implementing multilingual accessible lessons and also focussing on teaching the most successful multilingual learning strategies.

The results of the present study indicate the need for further development of multilingual didactics in geography lessons, as the suitability of multilingual multimedia, barrier-free, internally differentiating and therefore inclusive teaching materials is particularly suitable for sustainable knowledge transfer. In order to move beyond the experimental phase, multilingual geography teaching requires the further development of multilingual, barrier-free, inclusive practice models. The strategies of the most successful multilingual pupils in the final test represent an existing potential for future educational concepts. The decisive factor for learning success is how effectively a learning strategy is used. Research should focus on investigating how steering, control and understanding strategies can be specifically taught to lower-achieving pupils.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.R. and A.B.; methodology, N.R. and A.B.; validation, N.R. and A.B.; formal analysis, N.R. and A.B.; investigation, N.R. and A.B.; resources, N.R.; data curation, N.R.; writing—original draft preparation, N.R.; writing—review and editing, N.R. and A.B.; visualization, N.R.; supervision, A.B.; project administration, A.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study did not require Institutional Review Board approval. The data used in this study did not contain any personally identifiable information.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data can be made available.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Androutsopoulos, J. (2018). Social Multilingualism. In E. Neuland, & P. Schlobinski (Eds.), Handbuch sprache in sozialen gruppen (pp. 193–216). de Gruyter. [Google Scholar]

- Baechler, C. (2015). Influence du bilinguisme sur l’apprentissage d’une langue étrangère: Le cas d’enfants bilingues français et allemand apprenant l’anglais. In E. Fernández Amman, A. Kropp, & J. Müller-Lancé (Eds.), Origin-based multilingualism in the teaching of Romance languages (pp. 113–133). Franke & Timme. [Google Scholar]

- Baur, S., Goggin, M., & Wrede-Jackes, J. (2013). Der C-test: Einsatzmöglichkeiten im bereich daz. pro daz [The C-test: Possible applications in the daz area. pro daz]. Available online: https://www.unidue.de/imperia/md/content/prodaz/c_test_einsatzmoeglichkeiten_daz.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Becker-Mrotzek, M., & Roth, H.-J. (2017). Sprachliche Bildung—Grundlegende Begriffe und Konzepte. In M. Becker-Mrotzek, & H.-J. Roth (Eds.), Sprachliche bildung—Grundlagen und handlungsfelder (pp. 11–36). Waxmann. [Language education-fundamental terms and concepts. In M. Becker-Mrotzek, & H.-J. Roth (Eds.), Sprachliche bild-ung-Grundlagen und handlungsfelder (pp. 11–36). Waxmann]. [Google Scholar]

- Bialystok, E. (2017). The bilingual adaptation: How minds accommodation experience. Psychological Bulletin, 143(3), 233–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blossfeld, H.-P. (2016). Integration durch bildung. Migranten und flüchtlinge in deutschland: Gutachten. Waxmann. [Integration through education. Migrants and refugees in Germany: Expertise]. [Google Scholar]

- Böttjer, F., & Plöger, S. (2023). Mehrsprachige Bildungspraxis als Schonzeit für neu zugewanderte Schüler:innen. In E. Hack-Cengizalp, & M. David-Erb (Eds.), Mehrsprachigkeit und bildungspraxis (pp. 49–66). WBV. [Multilingual educational practice as a grace period for newly immigrated students. In E. Hack-Cengizalp, & M. David-Erb (Eds.), Multilingualism and educational practice (pp. 49–66)]. [Google Scholar]

- Bredthauer, S. (2019). Sprachvergleiche als multilinguale Scaffolding-Strategie. Zeitschrift für interkulturellen Fremdsprachenunterricht, 24(1), 127–143, [Language comparison as a multilingual scaffolding strategy. Journal of Intercultural Foreign Language Teaching, 24(1), 127–143]. [Google Scholar]

- Brem, S., & Maurer, U. (2018). Lesen als neurobiologischer Prozess. In U. Rautenberg, & U. Schneider (Eds.), Lesen. Ein interdisziplinäres Handbuch (pp. 117–140). Walter de Gruyter. [Reading as a neurobiological process. In U. Rautenberg & U. Schneider, Reading. An interdisciplinary handbook (pp. 117–140). Walter de Gruyter]. [Google Scholar]

- Budke, A. (2012). “I argue, therefore I understand”. On the Importance of Communication and Argumentation in Geography Teaching. In A. Budke (Ed.), Diercke—Kommunikation und argumentation (pp. 5–18). Diercke. [Google Scholar]

- Budke, A., & Kuckuck, M. (2017). Language in Geography Teaching. In A. Budke, & M. Kuckuck (Eds.), Language in geography teaching. Bilingual and language-sensitive materials and methods (pp. 7–37). Waxmann. Available online: https://www.pedocs.de/volltexte/2018/15410/pdf/Budke_Kuckuck_2017_Sprache_im_Geographieunterricht.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Budke, A., & Maier, V. (2019). Multilingualism in school and university—Experiences and perceptions of students in the teaching profession of geography. GW-Unterricht, 156(4), 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge (BAMF) Forschungszentrum Migration, Integration und Asyl (FZ); Bundesministerium des Inneren, für Bau und Heimat. (2020). Migrationsbericht der Bundesregierung (Migrationsbericht 2019). (Migrationsbericht/Bundesamt für Migration und Flüchtlinge (BAMF) Forschungszentrum Migration, Integration und Asyl (FZ)). [Research Centre for Migration, Integration and Asylum (FZ); Federal Ministry of the Interior, Building and Community. (2020). Migration Report of the Federal Government (Migration Report 2019). (Migration Report/Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF) Research Centre Migration, Integration and Asylum (FZ)). Berlin]. Berlin. p. 194. Available online: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-71263-8 (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Chamot, A., Kupper, L., & Impink-Hernandez, M. (1988). A study of learning strategies in foreign language instruction: Findings of the longitudinal study. Interstate Research Association. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, R. C., & Mayer, R. E. (2016). E-Learning and the science of instruction: Proven guidelines for consumers and designers of multimedia learning. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. (1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Education and Psychological Measurement, 20, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, V., & Singleton, D. (2014). Key topics in second language acquisition. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Coulmas, F. (2017). An introduction to multilingualism: Language in a changing world. OUP Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- de Boer, H., Donker, A. S., Kostons, D. D. N. M., & van der Werf, G. P. C. (2018). Long-term effects of metacognitive strategy instruction on student academic performance: A meta analysis. Educational Research, 24, 98–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dirim, I., Hauenschild, K., & Lütje-Klose, B. (2008). Einführung: Ethnische Vielfalt und Mehrsprachigkeit an Schulen [Introduction: Ethnic diversity and multilingualism in schools] (pp. 9–21). Brandes & Apsel. [Google Scholar]

- Dube, J., Schwinning, S., & Filipovic, J. (2023). Mehrsprachigkeit und Digitalisierung—Potenziale webbasierter mehrsprachiger Buchportale im Vergleich. In E. Hack-Cengizalp, & M. David-Erb (Eds.), Mehrsprachigkeit und bildungspraxis (pp. 147–166). WBV. [Multilingualism and digitisation-potentials of web-based multilingual book portals in comparison. In E. Hack-Cengizalp, & M. David-Erb (Eds.), Multilingualism and educational practice (pp. 147–166). WBV]. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K. A., Marsh, E. J., Nathan, M. J., & Willingham, D. T. (2013). Improving students’ learning with effective learning techniques: Promising directions from cognitive and educational psychology. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 14(1), 4–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Union (Ed.). (2020). EU languages. Brussels. Available online: https://europa.eu/european-union/about-eu/eu-languages_de. (accessed on 25 October 2024).

- Flavell, J. H. (1976). Metacognitive aspects of problem solving. In L. B. Resnick (Ed.), The nature of intelligence (pp. 231–235). Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Földes, C., & Roelcke, T. (Eds.). (2022). Handbuch mehrsprachigkeit (Vol. 22). Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co., KG. [Multilingualism handbook]. [Google Scholar]

- Franceschini, R. (2014). Neurobiologie der Mehrsprachigkeit und didaktische Umsetzungen: Ein Spagat. In H. Böttger, & G. Gabriele (Eds.), The multilingual brain. Zum neurodidaktischen umgang mit mehrsprachigkeit (pp. 208–220). Epubli. [Neurobiology of multilingualism and didactic realisation: A balancing act. In H. Böttger, & G. Gabriele (Eds.), The multilingual brain. On the neurodidactic handling of multilingualism (pp. 208–220). Epubli]. [Google Scholar]

- García, O. (2009). Bilingual education in the 21st century: A global perspective. Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Gebele, D., Zepter, A. L., Königs, P., & Budke, A. (2022). Metacognition in argumentative writing based on multiple sources in geography education. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 12, 948–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Georgi, V. (2011). Summary of key research findings and concluding remarks. In V. B. Georgi, L. Ackermann, & N. Karakaş (Eds.), Diversity in the teachers’ room: Self-perception and school integration of teachers with a migration background in Germany (pp. 265–274). Waxmann. [Google Scholar]

- Gogolin, I. (1988). Erziehungsziel Zweisprachigkeit: Konturen eines sprachpädagogischen Konzepts für die multikulturelle Schule. Bergmann + Helbig. [Bilingualism as an educational goal: Contours of a language pedagogical concept for the multicultural school. Bergmann + Helbig]. [Google Scholar]

- Goltsev, E., & Olfert, H. (2023). Mehrsprachige Methoden in der universitären Lehrkräftebildung: Erfahrungen und Wünsche der Studierenden. In E. Hack-Cengizalp, & M. David-Erb (Eds.), Mehrsprachigkeit und bildungsprxis (pp. 207–230). WBV. [Multilingual methods in university teacher education: Students’ experiences and wishes. In E. Hack-Cengizalp, & M. David-Erb (Eds.), Multilingualism and educational practice (pp. 207–230). WBV]. [Google Scholar]

- Grosjean, F. (2010). Bilingual: Life and reality (pp. 4–5). Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Grosjean, F. (2020). The bilingual’s language modes 1. The bilingualism reader (pp. 428–449). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Grünwied, G. (2017). Usability of products and instructions in the digital age. Handbook for IT specialists and technical writers. Publicis Pixelpark. [Google Scholar]

- Haberzettl, S. (2016). Bildungssprache im Kontext von Mehrsprachigkeit. An investigation of report texts of monolingual and multilingual pupils. Discourse Kindheits- und Jugendforschung/Discourse. [Educational language in the context of multilingualism. An investigation of report texts of monolingual and multilingual pupils. Discourse Kindheits- und Jugendforschung/Discourse]. Journal of Childhood and Adolescence Research, 11(1), 61–79. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/8e11/976769f4dbfe42c36fd2b4da7dac23b83ce4.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Hayakawa, S., & Marian, V. (2019). Consequences of multilingualism for neural architecture. Behavioral and Brain Functions, 15(6), 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heuzeroth, J., & Budke, A. (2020). The effects of multilinguality on the development of causal speech acts in the geography classroom. Education Sciences, 10, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinnenkamp, V. (2010). Dealing with multilingualism. Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte (APuZ), 8, 27–28. [Google Scholar]

- Hofer, B., & Jessner, U. (2019). Assessing components of multi-(lingual) competence in young learners. Lingua, 232, 102747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, R., & Kaiser, A. (2018). The new didactics—Metacognition as a key concept for teaching and learning. Grundlagen der Weiterbildung—Praxishilfen, 162, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Keimerl, V., Summer, T., Berschin, B., Birzer, S., Conrad, B., & Hess, M. (2023). Mehrsprachige Bildungspraxis in universitären Lehrveranstaltungen—Bildungswissenschaften im Dialog mit romanischer, englischer und russischer Fremdsprachendidaktik. In E. Hack-Cengizalp, & M. David-Erb (Eds.), Mehrsprachigkeit und bildungspraxis (pp. 231–246). WBV. [Multilingual educational practice in university courses-educational sciences in dialogue with Romance, English and Russian foreign language didactics. In E. Hack-Cengizalp, & M. David-Erb (Eds.), Multilingualism and educational practice (pp. 231–246). WBV]. [Google Scholar]

- King, A. (1994). Guiding knowledge construction in the classroom: Effects of teaching children how to question and how to explain. American Educational Research Journal, 31(2), 338–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konrad, K. (2010). Thinking Aloud. In G. Mey, & K. Mruck (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research in psychology (pp. 476–490). VS. [Google Scholar]

- Landesbetrieb IT.NRW Statistik und IT-Dienstleistungen. (n.d.). Available online: https://www.it.nrw/394-prozent-der-schuelerinnen-und-schueler-den-schulen-nrw-hatten-202021-eine (accessed on 5 December 2024).

- Landis, J. R., & Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33(1), 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, S., Huxel, K., Then, D., & Pohlmann-Rother, S. (2023). (“ich glaub, “ich würd’s nicht sofort unterbinden”)–Überzeugungen von Grundschullehrkräften zum didaktischen Umgang mit. In E. Hack-Cengizalp, & M. David-Erb (Eds.), Mehrsprachigkeit und bildungspraxis (pp. 103–122). WBV. [(I think, “I wouldn’t stop it right away”)-convictions of primary school teachers on the didactic handling of. In E. Hack-Cengizalp, & M. David-Erb (Eds.), Multilingualism and educational practice (pp. 103–122). WBV]. [Google Scholar]

- Lauring, J., & Selmer, J. (2012). International language management and diversity climate in multicultural organizations. International Business Review, 21(3), 262–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, A., & Brandt, H. (2023). Teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism: Novel findings and methodological advancements: Introduction to special issue. International Journal of Multilingualism, 20(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, V., & Budke, A. (2018). “Wie planen Schüler/innen? Die Bedeutung der Argumentation bei der Lösung von räumlichen Planungsaufgaben”. GW-Unterricht, 149(1), 36–49, [‘How do pupils plan? The importance of reasoning in solving spatial planning tasks’]. [Google Scholar]

- Mandl, H., & Friedrich, H. (2006). Handbuch lernstrategien. Hogrefe. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, R. E. (2001). Multimedia learning: Are we asking the right questions? Educational Psychologist, 36(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R. E. (2009). Multimedia learning (2nd ed.). University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer, R. E. (2014). The Cambridge handbook of multimedia learning (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mayr, G. (2020). Kompetenzentwicklung und Mehrsprachigkeit: Eine unterrichtsempirische Studie zur Modellierung mehrsprachiger kommunikativer Kompetenz in der Sekundarstufe II. Narr Francke Attempto Verlag. [Competence development and multilingualism: An empirical study on modelling multilingual communicative competence at upper secondary level]. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring, P. (2010). Qualitative content analysis (12th ed.). Fundamentals and Techniques. Weinheim. [Google Scholar]

- Mediendienst Integration (Ed.). (2024). Facts and figures. Mediendienst Integration. Available online: https://mediendienst-integration.de/integration/bildung.html (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Monserud, R. A., & Leemans, R. (1992). Comparing global vegetation maps with Kappa statistic. Ecological Modelling, 62, 275–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morawski, M., & Budke, A. (2017). Language awareness in geography education: An analysis of the potential of bilingual geography education for teaching geography to language learners. European Journal of Geography, 7(5), 61–84. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, R. (2004). Decreasing cognitive load for novice students: Effects of explanatory versus corrective feedback in discovery-based multimedia. Instructional Science, 32(1), 99–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murayama, K., Pekrun, R., Lichtenfeld, S., & Vom Hofe, R. (2013). Predicting long-term growth in students’ mathematics achievement: The unique contributions of motivation and cognitive strategies. Child Development, 84(4), 1475–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller-Benedict, V. (1997). Der Einsatz von Maßzahlen der Interkoder-Reliabilität in der Inhaltsanalyse. University of Flensburg. [The use of measures of intercoder reliability in content analysis. University of Flensburg]. [Google Scholar]

- Nawratil, U., Schönhagen, P., & Wagner, H. (2009). Die qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Rekonstruktion der Kommunikationswirklichkeit [Qualitative content analysis: Reconstruction of the reality of communication]. Available online: https://doc.rero.ch/record/232603/files/Nawratil_Sch_nhagen_2009_Die_qualitative_Inhaltsanalyse.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Niekamp, J., & Hu, A. (2001). Gibt es Ansätze einer Didaktik der Mehrsprachigkeit und Mehrkulturalität in der neuen Generation der Französischlehrwerke? In F. J. Meißner, & M. Reinfried (Eds.), Bausteine für einen neokommunikativen Französischunterricht. Lernerzentrierung, Ganzheitlichkeit, Handlungsorientierung, Interkulturalität, Mehrsprachigkeitsdidaktik (pp. 239–247). Narr, S. [‘Are there approaches to a didactics of multilingualism and multiculturalism in the new generation of French textbooks? In Franz-F.J. Meißner & M. Reinfried (Eds.), Bausteine für einen neokommunikativen Französischunterricht. Learner-centred, holistic, action-oriented, intercultural, multilingual didactics]. [Google Scholar]

- Oleschko, S., Weinkauf, B., & Wiemers, S. (2016). Praxishandbuch sprachbildung geographie. Sprachsensibel unterrichten—Sprache fördern. Klett. [Practical handbook language education geography. Language-sensitive teaching—Promoting language]. [Google Scholar]

- Pintrich, P. R., & De Groot, E. V. (1990). Motivational and self-regulated learning components of classroom academic performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82(1), 33–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pressley, M. (1982). Elaboration and memory development. Child Development, 53(2), 296–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Repplinger, N., & Budke, A. (2018). Is multilingual life practice of pupils a potential focus for geography lessons? European Journal of Geography, 9(3), 165–180. [Google Scholar]

- Repplinger, N. P., & Budke, A. (2022). The effects of multilingual teaching materials on pupils’ understanding of geographical content in the classroom. Journal of Curriculum and Teaching, 11(4), 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riehl, C. M. (2006). Aspects of Multilingualism: Forms, Advantages, Meaning. In M. Becker-Mrotzek, U. Bredel, & H. Günther (Eds.), Cologne contributions to language didactics. Series A. Multilingualism makes school. Gilles; Francke Verlag. Available online: http://koebes.phil-fak.uni-koeln.de/sites/koebes/user_upload/koebes_04_2006.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Riehl, C. M. (2014). Multilingualism. An introduction. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft (WBV). [Google Scholar]

- Riehl, C. M. (2018). Multilingualism in the Family and in Everyday Life. In A.-K. Harr, M. Liedke, & C. M. Riehl (Eds.), German as a second language. Migration-language acquisition-teaching (pp. 27–60). J.B. Metzler. [Google Scholar]

- Ritterfeld, U., Lüke, C., Starke, A., Lüke, T., & Subellok, K. (2013). Studien zur Mehrsprachigkeit: Beiträge der Dortmunder Arbeitsgruppe. Logos, 21(3), 168–179. Available online: https://eldorado.tu-dortmund.de/bitstream/2003/33690/1/2013%20Studien%20zur%20Mehrsprachigkeit.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2024). [Studies on multilingualism: Contributions from the Dortmund working group. Logos, 21(3), 168–179].

- Schramm, K. (2010). Metacognition. In C. Surkamp (Ed.), Metzler lexikon fremdsprachendidaktik [Metzler lexicon of foreign language didactics]. Approaches-methods-basic terms. J.B. Metzler. [Google Scholar]

- Schrödler, T., Rosner-Blumenthal, H., & Böe, C. (2023). A mixed-methods approach to analysing interdependencies and predictors of pre-service teachers’ beliefs about multilingualism. International Journal of Multilingualism, 20(1), 11–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tassinari, M. G. (2012). Assessing, promoting and evaluating competences for learner autonomy. FLuL- Fremdsprachen Lehrern und Lernen. Tübingen: Narr Francke Attempto. Kompetenzen Konkret, 41(1), 8–19. [Google Scholar]

- Thormann, E. (1994). Handlungsorientierung im Fremdsprachenunterricht. In Landesinstitut für Schule und Weiterbildung (Ed.), Results and perspectives of learning plan work (pp. 169–194). Landesinstitut für Schule und Weiterbildung. [Action orientation in foreign language teaching. In Landesinstitut für Schule und Weiterbildung (Eds.), Results and perspectives of learning plan work (pp. 169–194). State Institute for School and Further Education]. [Google Scholar]

- Tversky, B. (2005). Visuospatial reasoning, Cambridge handbook of thinking and reasoning (pp. 209–241). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Viebrock, B. (2019). Geography as a bilingual subject and the promotion of extended multilingualism and multiculturalism competence. In C. Fäcke, & F. J. Meißner (Eds.), Handbook of multilingualism and multiculturalism didactics (pp. 517–519). Narr Francke Attempto Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Weissenburg, A. (2013). “Der mehrsprachige Raum”—Konzept zur Förderung eines mehrsprachig sensiblen Geographieunterrichts. GW-Unterricht, 131, 28–41, [‘The multilingual space’ concept to promote multilingual-sensitive geography lessons]. [Google Scholar]

- Weissenburg, A. (2016). Plurilingual approaches to spatial education—Perspectives of primary schools in the German context [Doctoral thesis, Pädagogische Hochschule Karlsruhe]. Available online: https://phka.bsz-bw.de/frontdoor/index/index/year/2016/docId/62 (accessed on 24 October 2024).

- Würffel, N. (2006). Strategiengebrauch bei Aufgabenbearbeitungen in internetgestütztem Selbstlernmaterial. Narr. [Use of strategies when working on tasks in internet-based self-learning material]. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2008). Investigating self-regulation and motivation: Historical background, methodological developments, and future prospects. American Educational Research Journal, 45(1), 166–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).