Abstract

This paper investigates the case of digital leadership at the level of primary education based on in-service teachers’ digital competence and leadership styles in Western Greece. The objectives of this study are also to identify the effects of different kinds of leadership styles on teachers’ satisfaction and the adoption of digital practices and to identify gaps in educators’ digital skills. Quantitative design was supported, and for research purposes, a structured survey was administered to 105 primary school teachers. Different statistical analyses were conducted to examine the relationships among leadership styles, demographic factors, and digital competencies, with a specific interest in transformational leadership. The results indicate that transformational leadership plays a pivotal role in enhancing teachers’ satisfaction and fostering the adoption of digital leadership practices; hence, it is of special importance when promoting digital transformation in schools. The results point to a large gap in the digital competencies of teachers that targeted professional development programs could make up for. In terms of demographic variables, neither gender nor age was found to be a significant predictor of leadership style, while postgraduate education was found to be positively linked to more advanced leadership practices. These findings stress the importance of teachers in the process of shaping digital transformation and call for further research to develop a deeper understanding of what works in effective digital leadership in education that can support the development of high-performing digital ecosystems in schools.

1. Introduction

The rapid development of information and communication technology has played an enabling role in the establishment of new policies and changed the way information is accessed, shared, and applied. Because of the growth of the internet and the digital revolution of recent years, information has turned into one of the important resources needed by persons and organizations that could gain access to its value creation via its processing, analyses, and utilization for creativity and innovation purposes (Weber et al., 2022; Khaw et al., 2022). As for the constantly changing digital environment, leadership itself has hitherto taken on new meanings in so-called digital leadership to engage in innovation, altering behaviors, and driving business objectives through technology. The concept of digital leadership goes beyond digital administration or the mere electronic processing of routine work. The emphasis of digital leadership is to deploy technological tools and digital data to enhance organizational performance in a strategic manner that responds to dynamic market trends and ensures innovation in practice (Jameson et al., 2022; Antonopoulou et al., 2019; Li et al., 2021).

The educational sector will also not be left out as the bedrock for human and societal development. Schools are dynamic, constantly changing organizations that equally must adapt to new developments in technology and the shifting paradigms of digital times (Bankins et al., 2024; Saad Alessa, 2021; Antonopoulou et al., 2021a; Wart et al., 2017). Recent shifts toward distributed and collaborative forms of leadership, enabled using new technologies of communication, have reinforced the requirement for school leaders and educators to adopt digital technologies as part of effective teaching, learning, and administrative leadership (Peng, 2022; Gierlich-Joas et al., 2020; Ruel et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2022). Within this context, teachers play a pivotal role in shaping the digital transformation of schools. Teachers’ perceptions of leadership styles, coupled with their digital competencies, are critical to fostering digital practices and achieving educational innovation (B. Avolio et al., 1999; Vergne, 2020; Karakose et al., 2022; Achrol & Kotler, 2022). Despite the growing emphasis on digital leadership in schools, there remains a lack of clarity around how teachers experience and adopt leadership styles that support digital transformation, as well as the extent of their digital skills (Cunha et al., 2020; Dumulescu & Muţiu, 2021; Zhao, 2012; Nóvoa & Alvim, 2020; Antonopoulou et al., 2021b).

This study tries to cover these gaps by investigating teachers’ digital leadership and competence in primary education. Thus, this study investigates the connection of leadership styles to how teachers adopt digital practices or the relationship between the demographics of teachers, their levels of digital skills, and their perceptions of leadership. This research focuses on teachers, signaling their central role in effecting digital transformation in schools and the related need for targeted professional development to fill emerging digital competency gaps. In this direction, the current study contributes to the growing literature related to digital leadership in informing the behavioral patterns of teachers, who are considered key stakeholders for educational innovation. These findings can keep policy and practice informed to support schools in developing sound digital ecosystems meeting the demands imposed by the digital era.

Background and Rationale

Over the past decade, attention has been directed to the adoption of digital tools within institutions of learning, and it has also been one of the most important aspects in digital leadership. Many institutions across the world are embracing digital tools that are particularly geared toward enhancing students’ learning and increasing flexibility and mobility in educational contexts. The integration of digital tools in schools therefore has a rich theoretical underpinning towards meeting the diverse and personalized demands of modern learners (Jameson et al., 2022). Despite these advancements, schools continue to face challenges in creating engaging technology-rich environments. Many school settings still lack the necessary infrastructure or strategies to fully leverage digital tools, leaving students and teachers in less digitally influenced environments at a disadvantage. This divide between digitally advanced and under-resourced schools underscores persistent inequalities in digital resource allocation and implementation (Laufer et al., 2021; Alenezi, 2023; McCarthy et al., 2023).

Teachers play a central role in addressing these challenges. Therefore, they are the clear facilitators of digital literacy; their responsibility not only concerns using digital tools but also shaping an inclusive digital culture in schools. The literature mentions several barriers that exist on the ground for teachers: inadequate preparation and support, lack of resources, and ambiguous expectations of their role in digital leading and managing schools. The final barriers can create “digital contradictions” where the potential of digital tools in theory is not realized in practice. Most of the literature reviewed has highlighted a substantial lacuna in understanding the factors that may influence schools to adapt to digital use. Additionally, there is also a lack of knowledge and metrics on how to measure digital leadership in the context of schools. Though the need for digital leadership can be felt, the conceptualization and its actual implementation in schools are rarely explored (Berkovich & Hassan, 2024; Rodríguez-Abitia & Bribiesca-Correa, 2021; Behie et al., 2023).

A synthesis of recent findings shows a movement toward more organic, student-centered learning processes, supported by leadership models such as distributed leadership. Theories such as social practice and praxeology form a particularly useful framework for analyzing changes in leadership styles and their impact on digital transformation in schools (Dunbar & Yadav, 2022). However, research has largely neglected the role of digital leadership within decision-making processes and the specific competencies required by educators to lead digital innovation effectively. The current study fills these gaps by highlighting teachers’ perceptions of digital leadership and their competencies at the level of primary education. This study embraces an early-adopter approach in studying how teachers engage in digital tools and leadership styles, therefore deriving insights into how to promote digital innovation in schools. In view of the above limitations in the existing research on elementary education, the present study does not attempt to draw comprehensive conclusions but tries to contribute to the ongoing discourse by highlighting the importance of teacher-led digital transformation (Soubra et al., 2022; El Morabit & Manegre, 2024).

2. Literature Review

Digital technology use has become an integral part of our daily lives and is continuing to grow. This increase has also impacted the role that administrators have in educational institutions. New technologies are changing the ways schools operate, teachers teach, and administrators lead. While there is still no common theoretical framework widely accepted for illustrating the digitally connected world, educational systems are becoming unified with ubiquitous digital systems. The use of digital technologies provides a window into a growing world of information that is governed by data—rarely sparse and increasingly unstructured (Haleem et al., 2022; Iivari et al., 2020; Martins Van Jaarsveld, 2020). Changes in technology impact education and have implications for how students perform. Consequently, changes to the construct of interest in conjunction with new methods of measurement contribute to the recent popularity of Big Data Science (Javaid et al., 2021; Levin & Mamlok, 2021; Reddy et al., 2020; Sailer et al., 2021; Szymkowiak et al., 2021).

The term digital leadership is associated with digital technologies and suggests a new mechanism. For the purpose of this study, the driving mechanism of digital leadership is the supporting big data technologies. A quick skim through the literature highlights theories, ideas, and thoughts of digital leadership that are grounded in today’s technology. However, this comes at a cost—the literature is rich in theories but largely devoid of any discussion related to the practical implications of digital leadership (Theodorakopoulos et al., 2024a). Despite the lack of published work on a wide variety of theoretical constructs of digital leadership, data mining techniques are slowly transforming the educational landscape. Data mining, educational data mining, and/or learning analytics are collectively a set of statistical and machine learning methods, algorithms, models, tools, software, and programming languages. Support for these data mining techniques has yielded great success. Those who use them creatively have consigned anecdotes to the realm of literature and have shown great promise in negating the endowment effect that negatively impacts the traditional classroom (Stamatiou et al., 2022; Bakalis et al., 2024). However, by analyzing and transforming digital data, a growing number of student and educational practitioner-friendly software packages have made big data less jargon-like and more easily available to practitioners. Given these circumstances, this study moves in a different direction than previous work on digital leadership. It specifically examines data for a given teacher’s school class and analyzes the teacher as a digital practitioner prior to transitioning to a big data set (Chatterjee et al., 2023; Benitez et al., 2022; Porfírio et al., 2021).

Leadership has been evolving over the past few decades, moving toward decentralization and diffused processes due to accelerations in social, economic, political, and technological change. So-called “new leadership” theories highlight the importance of processes aimed at involving and empowering people and communities to develop capacities that value the knowledge and expertise of the group (Navaridas-Nalda et al., 2020). In this context, the development of digital leadership in schools has been recognized as a key component in several educational approaches, as it represents a behavior based on a combination of skills and characteristics linked to individuals aiming to promote a shared vision about digital technology (Karakose et al., 2021). Digital leadership is often referred to in the education literature, and more specifically in the field of K-12, as the cognitive, behavioral, and dispositional attributes of a leader that promote the effective use of digital technologies and the attainment of educational goals and targets (Hamzah et al., 2021; AlAjmi, 2022; de Araujo et al., 2021; Eberl & Drews, 2021; Sortwell et al., 2024).

To this aim, individuals will be able to model an understanding of how to develop their own digital capabilities, like vision and the will and ability to act in new and creative contexts with a continuous eagerness to learn, plus a willingness to collaborate, to question the status quo, having the courage to try alternatives, engaging in self-care and self-awareness, and engaging in reflection and self-evaluation. A digital leader must reflect and promote a vision of digital fluency up to a spirit of innovation, probably more extreme in perspective, because they care about cultural and societal evolution more than average. Practicing digital leadership by initially blending analog and digital technological elements and expectations will afford the tool-based and sector-based experience required for a digital leader (Benitez et al., 2022; Navaridas-Nalda et al., 2020; Karakose et al., 2021; Hamzah et al., 2021). Moreover, it is still argued in educational settings that digital leadership should represent an innovative type of leadership behavior compared to traditional leadership theories shaped in the pre-digital era (AlAjmi, 2022). The leader is influenced by the environment, and this type of environment can foster a digital leader state of mind (Gkintoni et al., 2022; Erhan et al., 2022; Schmidt & Tang, 2020; Gapsalamov et al., 2020; Høydal & Haldar, 2022).

2.1. Digital Transformation of School Administration

In most national educational systems, digitization has entered the school administration area. Through the collection and analysis of data related to primary education providers, educational systems can be aware of improvement points and performance measures and derive appropriate strategies (Zancajo et al., 2022). Educational organizations can take advantage of benefits such as cost-effective and personalized real-time services, data-driven analytics using big data platforms, and robust cybersecurity systems. Modern organizations, no matter their field of operation, now have access to powerful tools that use big data and analytic techniques to create knowledge, unlock executive and managerial skills, and make decisions to accelerate growth (Ronzhina et al., 2021; Theodorakopoulos et al., 2018; Vasilev et al., 2020). Adopting digital solutions, sometimes called connecting different public services under the same digital umbrella, fulfills a wide concept, simplifying and facilitating the citizen’s journey through the public sphere (Halkiopoulos & Gkintoni, 2024; Cone et al., 2022; Antonopoulou et al., 2023; Bormann et al., 2021; Gousteris et al., 2023). The application of digital tools is of benefit in terms of governance. Through a government’s supportive framework, the decision-making process speeds up. One subcategory in this context, i.e., e-education, is also relevant. By adopting different digital tools, schools can transform processes and methodologies. Common terms are e-administration and e-procurement. When the classroom environment is integrated and permanently connected to the digital world outside the school gates, e-classroom tools become relevant. That is, when the connected and present concept is available for students, their educational journey becomes possible (Kickbusch et al., 2021; Gasser et al., 2020). The focus shifts from receiving knowledge to being involved in the learning journey. Handling personal devices in primary schools involves controversy. Pupils’—and their parents’—acculturation to the various devices in general use in a digital society is no minor detail, yet the issue between supporting the applications that pupils wish to use to become part of a society that has already adopted them and the concern with deregulated use exists (Nochta et al., 2021; Malodia et al., 2021; Zhang & Chen, 2024; Li et al., 2020; Luan et al., 2020).

In Greece, in all public sector services, and certainly in educational institutions, most, if not all, work is conducted electronically. The communication of school units with each other, but also with the respective educational directorates; the processing of all electronic correspondence; the dissemination of experiences and results, but also more practical issues concerning the operation of schools, such as data, positions, seniority, the leaves of teachers, grades, absences, personal data, and the timetables of students, are now, and have been for several years, registered and processed through a single information system that aims to provide computerized support for school units and the administrative structures of education in Greece, myschool (myschool.sch.gr) (accessed on 21 January 2025). Through the portal www.gov.gr, in the context of e-government, dozens of educational “acts”, such as certificates, applications, registrations, transfers, electronic registers, etc., are fulfilled electronically (Theodorakopoulos & Theodoropoulou, 2024; Kuziemski & Misuraca, 2020; Pope et al., 2024; Theodorakopoulos et al., 2024b; Dexter & Richardson, 2020).

In addition, the Panhellenic School Network (PSN), the national network and internet service provider (ISP) of the Ministry of Education, the network that connects all school and administrative units of primary and secondary education, ensures the digital presence of all school units. It provides and promotes advanced services for the administrative organization and support of the educational process, such as e-mail, teleconferencing, the hosting of websites and blogs, the geospatial imaging of school units, electronic inventories of technological equipment, school library management systems, modern and asynchronous tele-education platforms, multimedia services, etc. (www.sch.gr). Especially in recent years, considering the COVID-19 pandemic and protection measures, the need for the digital transition of school units, both at the pedagogical and administrative levels, has become more imperative for the smooth promotion of the educational process. Nowadays, the classroom has become an e-classroom, the blackboard has become a shared screen, all educational meetings have become videoconferences, and webinars and modern and asynchronous tele-education platforms have become the new, now consolidated, reality.

A new public administration unit, the Ministry of Digital Governance, was established in July 2019, and its mission is “the continuous promotion of the digital and administrative transformation of the country and its adaptation to the rapidly changing international environment, through the formulation of the framework, rules and operating conditions, with the aim of optimizing the operation of the state…” (Government of Greece, n.d.). In 2020, this ministry issued the Digital Transformation Paper 2020–2025 which outlines the planning and guidelines that will be used to implement the digital transformation of the Greek society and economy (digitalstrategy.gov.gr, 27 January 2025). The objectives of digital transformation, among others, are the development of the digital skills of all Greeks, the strengthening and support of digital innovation, and the integration of modern technologies in all sectors. In the field of education, in cooperation with the Ministry of Education and Religious Affairs, the aim is to “strengthen the digital experience at every level of education, including the administration of education, the educational process and services to citizens” (digitalstrategy.gov.gr). All the above-mentioned services simplify procedures, eliminate the bureaucratic structure of administrations, facilitate administrative work, digitize services, and contribute to the upgrading of the administrative and pedagogical work of schools. However, we are talking about a huge amount of digital data and information that not everyone can and should have access to. This raises serious issues of the access, management, encryption, and security of personal and sensitive data (which are not within the scope of this paper).

2.2. The Role of School Directors as Digital Leaders

The role of School Directors as visionary leaders in technology and digital innovation holds immense significance in today’s rapidly evolving educational landscape. In an era where technological advancements are reshaping the way we teach and learn, School Directors play a pivotal role in driving the integration of technology into the fabric of education. As leaders, School Directors must possess a deep understanding of emerging technologies and their potential to transform learning experiences. They need to be aware of the latest trends, tools, and platforms, making informed decisions about their implementation in the school ecosystem. Their visionary approach is crucial for harnessing the power of technology in optimizing teaching methodologies, enhancing student engagement, and fostering a future-ready mindset among the school community (Karakose et al., 2022; Navaridas-Nalda et al., 2020; Gomez et al., 2022).

School Directors’ digital leadership extends beyond just incorporating technology into classrooms. It encompasses cultivating a culture of innovation that embraces digital literacy, critical thinking, and creativity among both students and staff. They must nurture a supportive environment that encourages experimentation, risk-taking, and collaborative problem-solving. Furthermore, School Directors should collaborate with stakeholders at all levels to develop a comprehensive technology plan that aligns with the school’s vision and goals (Almusawi et al., 2021; Pan et al., 2022). This involves engaging teachers in professional development opportunities that empower them to effectively utilize digital tools and resources. Directors must provide ongoing support and training, ensuring that educators have the knowledge and skills to leverage technology in impactful ways (McCarthy et al., 2023; Benitez et al., 2022; Richardson et al., 2021; Fuad et al., 2022; Torres, 2022; Agasisti et al., 2020).

Moreover, as leaders in technology and digital innovation, School Directors must advocate for equitable access to technology resources. They need to address the digital divide, ensuring that every student has equal opportunities to benefit from technology-enhanced learning experiences (Leithwood, 2021; Theodorakopoulos et al., 2024b). This may involve securing funding, forging partnerships with technology companies, and exploring creative solutions to bridge the gap. In conclusion, the role of School Directors as leaders in technology and digital innovation is multidimensional and far-reaching (Halkiopoulos et al., 2022; Masonbrink & Hurley, 2020; Nevill et al., 2023; Antonopoulou et al., 2022; Martinez & Broemmel, 2021; Gallegos-Rejas et al., 2023). They must possess a holistic understanding of technology integration, spearhead a culture of innovation, collaborate with stakeholders, empower educators, and champion digital equity (Gandolfi et al., 2021). By embracing their leadership role, School Directors can transform education, equipping students with the necessary skills and competencies to thrive in the digital age (Varma et al., 2023; Alkureishi et al., 2021; Faturoti, 2022).

2.3. Digital Leader Characteristics

A digital leader is one who combines strategies, techniques, and forms of leadership centered on technology and its use, aiming at innovation and change, to facilitate learning and improve the efficiency of an organization (B. Bass & Avolio, 1994). Researchers (Gandolfi et al., 2021; Varma et al., 2023; Alkureishi et al., 2021; Faturoti, 2022; B. Bass & Avolio, 1994) argue that if a school principal promotes technology and innovation successfully, then they are more effective. Based on what we said above about the digital transformation of school units, leaders—principals—must be aware of all the challenges they will have to face, have a clear vision for the development of their school, and emphasize their human resources. This can be ensured by starting from the identification of colleagues who will be able to contribute substantially to this transformation and motivating and training them to become truly helpful and confirming that they have the strength and fortitude to overcome their own expectations of themselves and transform from “conventional” to “digital” leaders (Antonopoulou et al., 2021a, 2021b).

Digital leaders must therefore have a set of knowledge and skills that allow them to develop innovative ICT-related standards at all stages and levels of an organization in planning, organizing, managing, and controlling both administrative and pedagogical work. Digital leaders must first view the use of new technologies positively and be able to effectively use digital ICT tools in both administration and teaching (Gkintoni et al., 2024). According to studies like (Antonopoulou et al., 2021a, 2021b), digital leaders must perform the following:

- ▪

- Define and promote the digital vision and technological goals of school units.

- ▪

- Stimulate technological change in schools.

- ▪

- Use ICT and the internet themselves and take advantage of the opportunities they offer.

- ▪

- Provide resources for schools’ technological infrastructure and its continuous improvement and upgrading, based on the needs of students and teachers.

- ▪

- Strengthen policies to promote innovation and develop professionally in the field of technology and its integration in pedagogical work.

- ▪

- Raise awareness of the uses of ICT and their importance to the educational workforce and provide professional and technological development opportunities for teachers as well.

Moreover, it is important that there is a systematic monitoring of ICT developments, as technological training should be renewed and updated frequently. In addition, a key characteristic of digital leaders is their ability to promote teamwork, interaction, and communication among all members of the school. The digital world requires collaboration, experimentation, and variety in thoughts and actions, as well as the continuous commitment of all members towards this direction; therefore, continuous development through training sessions, motivation, and the freedom of access for teachers to schools’ technological infrastructure contributes to the acquisition of educational and technological skills for all. E-leaders must practically guide and reinforce the required change in the entrenched school culture, commit to the change, and monitor its progress and development. In other words, they need to have both strategic and business and digital knowledge (www.eskills-lead.eu) (accessed on 21 January 2025). Principals who are comfortable with ICT more readily promote its integration into both the educational process and administration (Baylor & Ritchie, 2002).

In 2001, the International Society for Technology in Education (ISTE), a global organization active in technology education curricula that aims to improve learning, support teaching, and guide technology professionals (International Society for Technology in Education, 2008) published the National Educational Technology Standards for Administrators (NETS-A). In addition, it issued ISTE standards for coaches, teachers, computer educators, and students, all of which are essential for the effective use of technology in schools to support learning and enhance school performance. In 2009, the NETS-A was updated to consider the entry of new technologies into the workplace and the need for managers to be able to create learning environments aligned with the evolution of technology. It therefore includes five (5) standards that represent skills that school leaders–managers should have in an ever-changing technological environment. According to these standards, technology leaders should conduct the following:

- ▪

- Provide a technology-focused vision for all members of the educational unit.

- ▪

- Create and maintain a digital learning culture.

- ▪

- Promote an environment in which technology is used and digital resources are exploited.

- ▪

- Manage their schools with an effective use of technology.

- ▪

- Model and understand social, ethical, and legal issues related to digital technologies (Richardson et al., 2012).

In addition to expertise, digital leaders must have the ability to manage the increasing complexity of ICT use, to cope with constant changes, to recognize and exploit digital trends and opportunities, to have an open mind, to take initiatives and risks, to be receptive to modernization, and to not be afraid to follow new trends. Digital leaders also need to have empathy; be supportive and communicative; and promote a positive climate of cooperation and solidarity with the aim of a more people-centered leadership that will lead to greater satisfaction, empowerment, and commitment of human resources (Manders, 2008). Leadership, in this way, can extend to more than one person and take place through the collegiality, inclusivity, interaction, and co-performance of members who are jointly aiming for the digital vision of their school. This may refer, in addition to the transformational type of leadership of course, to the distributed leadership style. After all, researchers in the literature (Leithwood et al., 1999) argue that all leaders choose which leadership style to follow from the same set of leadership practices, but what really differs is not the leadership style per se but the way one practices it (Hallinger, 2005).

Utilizing human resources according to their potential; involving everyone in the digital transformation of the school unit; training them to upgrade and develop their knowledge and skills, both pedagogical and administrative; involving everyone; and creating long-term “value” for all in the digital upgrading of the school often make it difficult to distinguish between formal and informal leaders. The collective action and reciprocal nature of leadership is often more important than the title of leader and reflects the practice of distributed leadership (Spillane et al., 2001).

2.4. Digital Skills

Rapid technological development; the innovations of the modern era; and the appropriation of social media, AI (Artificial Intelligence), robotics, the STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, Mathematics) model, and the IoT (Internet of Things) have shaped a new social, business, and educational reality. Employees, like apprentices, of the modern era are called upon to meet new challenges and acquire skills that will make them more “modern”, productive, efficient, and ready to cope with rapid digital changes. The effort to continuously renew and upgrade the skills of professionals and workers to enable lifelong learning is key to the future sustainability of any modern economy at all levels (Digital Skills and Jobs Platform, 2023). Digital literacy is essential for working, learning, and active participation in society. It refers to the use of the range of digital technologies and achievements to inform, communicate, and solve problems in all aspects of life in an appropriate way. This also implies a safe, ethical, and responsible consciousness in the use of technology, as well as respect for digital ethics and human rights (Akcil et al., 2017). That is, digital literacy must be consistent with digital citizenship, the rules of conduct that govern the responsible and correct use of digital technologies. The European Commission’s Digital Skills and Job Coalition (DSJC) has identified the need for digital skills development in four (4) groups:

- ▪

- Digital skills for all: fostering digital skills for all citizens to become digitally competent and active in today’s social reality.

- ▪

- Digital skills for the workforce: cultivating digital skills in workers, both active and potential, to enable them to contribute to the development of the digital economy.

- ▪

- Digital skills for ICT professionals: cultivating digital skills for new technology professionals in all sectors of industry.

- ▪

- Digital skills in education: cultivating digital skills from a lifelong learning perspective for both students and teachers (European Commission, 2017).

Since 2015, the European Commission has been measuring citizens’ digital skills with the Digital Skills Indicator (DSI). According to Eurostat’s DSI, in Greece, in 2020, the population with digital skills was only 52% of adults, with the European average being 61%.

In general, Greece’s performance is low compared to the rest of Europe (25th out of 27 countries) in terms of the DSI. In 2017, Greece, Croatia, and Italy were the lowest-performing countries in the DSI in terms of broadband infrastructure deployment and quality. Similarly, in 2018, Greece, together with Romania and Italy, had the weakest performance in the Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI). Denmark, Finland, and Estonia, on the other hand, had the highest performance in the use of digital technologies, especially in their public sector and public administration (Digital Skills and Jobs Platform, 2023). This makes it imperative that Greeks participate in training programs to acquire Ministry of Digital Governance, 2023measures citizens’ online activities in the last quarter in five specific areas:

- ▪

- Information literacy and data literacy.

- ▪

- Communication and cooperation.

- ▪

- Digital content creation.

- ▪

- Security.

- ▪

- Problem-solving.

This index is also used to monitor the European Union’s target of reaching at least 80% of the EU population having at least basic digital skills by 2030 (European Commission, 2017).

As highlighted in the European Union Digital Education Action Plan (2021–2027), the development of digital competences by teachers is among the key areas for action for a high-performance digital education ecosystem (Digital Skills and Jobs Platform, 2023). Training in such a modern digital reality is a key and very important pillar for the development and evolution of learners and trainers. It requires the involvement of all stakeholders—teachers, learners, parents, and employers—so that everyone can become digitally “competent” and contribute accordingly (Digital Skills and Jobs Platform, 2023). More specifically, in terms of education, educational institutions, and in this case schools, should not function as closed communities but as part of the wider environment in which they must adapt and perform. Moreover, as mentioned above, they need to adopt changes and innovations in both their structure and operation to cope with the new digital reality. A decisive role in this is played by the school principal who must follow the changes and become a digital leader who, along with having the digital characteristics that we mentioned above, needs to cultivate some digital skills.

For over a decade, the European Commission has been at the forefront of monitoring the evolving demand and supply of e-skills. Thus, it promotes the user competences required for the effective application of ICT systems and devices; the use of common software tools, as well as specialized tools supporting organizational and business functions; and, more generally, the “digital literacy” of individuals, i.e., the skills needed to use ICT confidently and critically for work, leisure, learning, and communication. The European Commission also promotes the e-business skills needed to exploit and use the opportunities provided by ICT, and particularly the internet, for new ways of conducting business and administrative and organizational processes (Publications Office of the European Union, 2013). This means that greater investment is needed in high-tech leadership skills where people are at the center. The European Agenda for High-Tech Leadership Skills, through dozens of experts who contributed to its development, proposes six (6) strategic areas where Europe can seize the challenges and opportunities for digital-ready technology leaders in industry, education, and training (European Commission, 2017). Europe’s six (6) strategic priorities for digital leadership skills are cloud computing, Big Data Analytics, social media, the Internet of Things, IT Legacy Systems, and mobile apps. The ability of a country to strengthen efforts to continuously renew and upgrade the skills of its workforce is the most important factor in ensuring its future presence and competitiveness. In education, investment in digital teaching and learning resources, as well as the complementary development of digital competences by teachers, is among the key areas for action for a high-performance digital education ecosystem, as highlighted in the EU Digital Skills and Jobs Platform 2021–2027 (Digital Skills and Jobs Platform, 2023).

More specifically, based on the above and according to (Antonopoulou et al., 2021a), a list of areas that a digital leader in education should have digital skills in to be able to guide the members of the school community towards the digital era and its needs, but also to make the most of the opportunities and possibilities offered by ICT, is presented as follows:

- ▪

- Big data.

- ▪

- Cloud computing.

- ▪

- ERP systems.

- ▪

- Social media.

- ▪

- Mobile apps and Web Development.

- ▪

- Digital architecture.

- ▪

- Security.

- ▪

- Complex business systems.

2.5. Aim of This Research

The purpose of this research is to explore the leadership styles that primary school teachers have adopted or would adopt, focusing on their use of digital leadership. The current study aims to establish which leadership styles are the most preferred or in practice among teachers, the relationship between these styles and leadership outcomes, and which digital competencies teachers consider necessary for digital leadership. This study also explores the level of teachers’ digital competencies themselves and whether they meet the expectations arising in light of schools’ approaches to digital leadership. This investigation provides further insight into how teachers describe their roles in fostering this digital transformation and points toward how leadership styles, teachers’ digital competencies, and educational outcomes are related. The individual questions that are posed to be answered through this research are as follows:

[RQ1] What leadership style do primary school teachers apply or prefer in their professional roles, and how does it relate to digital leadership?

[RQ2] How do demographic and professional characteristics influence the leadership styles adopted by primary school teachers?

[RQ3] What are the digital skills recognized and possessed by primary school teachers, and how do these skills support their role in digital leadership?

[RQ4] Are teachers’ digital skills influenced by demographic and professional characteristics, such as age, gender, and educational background?

[RQ5] How are teachers’ digital skills associated with the leadership styles they adopt, particularly in the context of digital leadership?

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Sample

The sample of the survey consists of 105 teachers, including permanent teachers, substitute and hourly paid teachers, teachers, principals, and teachers of specialties of primary schools in the region of Western Greece. Responses were collected during the last two months of 2022.

The sampling in this study was conducted in a manner that represents a sample of primary school teachers that can be used to capture varied demographic and professional characteristics. A purposive kind of sampling was performed to target teachers who are directly involved in classroom teaching and the integration of digital tools, which also aligns with the focus of this study on teachers’ perceptions of leadership styles and their digital competencies. The sampling process included outreach to a variety of schools within the region to ensure diversity in factors such as school size, geographic location, and organizational structure.

3.2. Data Collection

The data for this study were collected using a structured questionnaire specifically designed to assess leadership styles, digital leadership, and associated digital competencies among primary school teachers. The questionnaire was distributed electronically via the Google Forms application, reaching participants through email communication with primary schools in the Western Greece region and through professional networks. This method facilitated broad participation and efficient data collection.

The questionnaire was divided into three parts:

- Demographic Information:The first section gathered the key demographic and professional characteristics of participants, such as gender, age, educational level, employment type (e.g., permanent, substitute), years of service, specialization, and school size.

- Leadership Style Measurement:The second section employed the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ) (Form-5x), a widely recognized instrument developed by B. M. Bass (1985) and refined over time. This validated tool measures three leadership styles—transformational, transactional, and passive–avoidant—as well as leadership outcomes related to extra effort, satisfaction with leadership, and perceived effectiveness.

- ▪

- The MLQ consists of forty-five closed-ended questions:

- ➢

- Thirty-six questions assess the nine dimensions of the three leadership styles (four questions per dimension).

- ➢

- Nine questions evaluate leadership outcomes.

- ▪

- Transformational LeadershipParticipants rated their agreement with statements such as the following:

- ➢

- “I articulate a vision that inspires and motivates others.”

- ➢

- “I encourage creativity and innovation in solving problems.”

- ➢

- “I pay attention to individual needs and provide support to help others grow.”

- ➢

- “I act as a role model and inspire others through my actions.”

- ▪

- Transactional LeadershipSample items include the following:

- ➢

- “I reward achievements to motivate my colleagues.”

- ➢

- “I monitor performance closely to ensure standards are met.”

- ➢

- “I resolve problems when deviations occur.”

- ▪

- Passive–Avoidant LeadershipExamples of statements include the following:

- ➢

- “I delay making decisions until problems escalate.”

- ➢

- “I avoid involvement in critical decisions.”

- ➢

- Leadership outcomes were measured with items such as:

- ➢

- “My leadership inspires extra effort from my team.”

- ➢

- “I am satisfied with the effectiveness of leadership in my school.”

- Digital Leadership and Skills:The third section consisted of seven closed-ended questions adapted from prior research (e.g., Antonopoulou et al., 2021b), designed to assess participants’ perceptions of digital leadership and self-reported digital skills. Items were rated on a five-point Likert scale from “Not at all” (1) to “Almost always” (5). Examples of statements include the following:

- ➢

- “I integrate digital tools into my leadership practices.”

- ➢

- “I prioritize cybersecurity in my school’s digital environment.”

- ➢

- “I demonstrate expertise in using cloud computing, social media, and mobile apps for management tasks.”

- ➢

- “I foster a culture that embraces digital transformation and innovation.”

Participants also rated their proficiency in specific digital skills, such as the following:- ➢

- Web Development and Tools.

- ➢

- Social media.

- ➢

- Cloud computing.

- ➢

- Cybersecurity.

- ➢

- Mobile apps.

- ➢

- Big Data and analytics.

- ➢

- Digital architectures.

3.3. Instrument Validation Process

The instrument was pretested on 15 teachers of the target population to ensure that it was both valid and reliable. The participants were required to answer the survey and comment on the clarity of the questions, relevance to the study objectives, the appropriateness of response scales, and their understanding of the instructions. Their comments were used to revise the wording and structure of several items. In fact, the iterative process fitted the instrument to the primary school teachers while keeping its usually measured constructs intact.

In this research, Cronbach’s alpha was used as a statistical means of testing the reliability of the internal consistency for the questionnaire scales. It emerged that all sections had high reliability values, such as 0.916 for transformational leadership, 0.776 for transactional leadership, 0.791 for passive–avoidant leadership, 0.947 for leadership outcomes, and 0.895 for digital leadership. The high alpha values proved that the items within each scale are reliable measurements for their intended constructs.

Items were thus developed from an extensive literature review on leadership styles, digital leadership, and educational competencies under the consideration of theoretical frameworks. A further validation of the instrument’s content was enabled by expert input: two academic professionals that specialized in the fields of educational leadership and digital transformation reviewed the contents, confirming that the constructs of interest were represented, theorized according to the proposed models, and applied in primary education. An Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) run on the pilot data was used to verify construct validity. From these analyses, the items were loaded on different factors, ensuring distinctiveness for each one, regarding the theoretical dimensions of leadership and digital competencies. Regarding adaptation, the MLQ and the part about digital leadership were adapted into the educational context in Western Greece by using its language and examples. Precautions were taken to minimize biases while collecting data. Electronic distribution allowed for anonymity, reducing social desirability bias. Questions were worded neutrally, preventing leading; the format of the Likert scale can capture nuanced opinions. These methods combined enhanced the trustworthiness of the instrument and ensured that the reliability and validity of the data collected can be trusted.

3.4. Statistical Processing

The responses collected from the completed electronic questionnaires were checked for accuracy and completeness, coded, and entered into a database of the statistical software SPSS (version 26). Each row of the database contains the total number of responses of a respondent, while each column contains the total number of responses to a question. The questions asked by the sample members are variables that can be classified into categorical (demographic characteristics, digital attributes) and ordinal (leadership style, leadership outcome, number of digital attributes) questions. As for frequency, percentage tables, percentage bar charts, and pie charts were used for the descriptive statistical analysis of the categorical variables.

For the descriptive statistical analysis of the ordinal variables, the statistical measures of minimum value, maximum value, mean value, and standard deviation, as well as the bar charts of means, were used. Correspondingly, for the inferential statistical analysis, the non-parametric Mann–Whitney (for comparing the means of two independent samples), Kruskal–Wallis (for comparing the means of three or more independent samples), and Wilcoxon Signed Rank (for comparing the means of two related samples) tests were used. To investigate the possible correlations between different leadership styles (ordinal variables), Spearman’s rho correlation coefficient was used. Further, the possible dependence between ordinal variables was investigated through simple linear regression. The reliability of the different scales of questions was measured using Cronbach’s alpha reliability index, where values above 0.7 are considered satisfactory. Finally, a significance level of α = 0.05 was used for the hypothesis testing of all statistical tests, correlations, and linear regressions.

4. Results

Most of the survey participants are female (81.0%), while about one-fifth are male (19.0%). Most respondents are in the age categories of 41–50 (37.1%) and 51–60 (32.4%), have only a bachelor’s degree (61.0%), and are tenured teachers (82.9%). A total of 39.0% of the sample members have more than 20 years of experience, and the majority (69.5%) teach in 6–12/elementary schools. Finally, 75.2% of the sample consists of teachers, and only 10.5% are or have been principals in the past (Table 1).

Table 1.

The demographic characteristics of the sample (N = 105).

4.1. General Picture of Leadership Styles

Using the Multifactor Leadership Questionnaire (MLQ), participants were asked to rate the extent to which they exhibit specific leadership behaviors. Responses were scored on a scale from 1 (Not at all) to 5 (Almost always), based on 43 questions that measured their leadership style as managers or prospective managers. Digital leadership was assessed similarly, using five relevant questions. For each participant, mean scores were calculated for each leadership style, resulting in individual scores ranging from 1 to 5. Higher scores indicated a stronger adoption of the respective leadership style. Reliability analysis demonstrated satisfactory internal consistency across all scales, with Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from 0.776 (transactional leadership) to 0.947 (leadership outcome). The digital leadership scale also demonstrated strong reliability, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.895, indicating that the five items assessing this style could be combined into a single composite score. Descriptive statistics for the variables are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Description of variables under consideration.

The results indicate that participants adopt (or would adopt) transformational leadership to a high degree (M = 4.10, SD = 0.58) and transactional leadership to a moderate degree (M = 3.68, SD = 0.62). The difference between these two leadership styles was statistically significant (p < 0.05). Conversely, participants avoided adopting passive–avoidant leadership (M = 1.69, SD = 0.59), which was adopted to a significantly lower degree than both transformational and transactional leadership (p < 0.05). These findings are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Exploring differences between leadership styles.

4.2. Leadership Styles by Demographic Characteristics

In order to determine whether demographic characteristics have a statistically significant effect on the leadership style adopted (or would be adopted), the non-parametric Mann–Whitney and Kruskal–Wallis statistical tests were used.

First, we found that the gender of the respondents does not affect the extent to which they adopt (or would adopt) each leadership style. Any differences presented are not statistically significant (p > 0.05) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Leadership style—gender.

Similarly, age categories do not seem to have a statistically significant effect on leadership styles (p > 0.05) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Leadership style—age.

In terms of the level of study, it seems that respondents with a postgraduate degree adopt (or would adopt) transformational and transactional leadership more often and passive leadership less often compared to their colleagues with only a degree. However, the differences presented are not statistically significant (p > 0.05) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Leadership style—level of education.

In contrast, work relationships appear to have a statistically significant effect on leadership styles. Permanent teachers adopt (or would adopt) transactional (M = 3.75, SD = 0.60) and passive leadership (M = 1.73, SD = 0.62) to a greater extent than their substitute–temporary colleagues (M = 3.36, SD = 0.67 and M = 1.45, SD = 0.36, respectively). The number of years of service does not seem to have a statistically significant effect on the leadership style adopted (although in this sample, digital leadership seems to be more prominent among teachers with fewer years of service) (Table 7).

Table 7.

Leadership style—work relationship.

The same is not the case, however, with the organic nature of the school in which the research participants teach (Table 8).

Table 8.

Leadership style—years of service in primary education.

The higher the organicity of the school, the more transformational leadership is (or would be) adopted (p < 0.05) (Table 9).

Table 9.

Leadership style—organization.

Finally, the present or former status of the manager and the respondents’ specialty do not seem to influence the adopted leadership style, leadership outcome, or digital leadership (p > 0.05) (Table 10).

Table 10.

Leadership style—have you been or are you a manager?

However, it should be mentioned that in this sample, past or present managers demonstrate less digital leadership, while those holding the IT specialty demonstrate higher levels of digital leadership compared to their other colleagues (the differences are, however, not statistically significant, with p > 0.05) (Table 11).

Table 11.

Leadership style—specialty.

4.3. Relationship of Leadership Outcomes with Leadership Styles

Spearman’s non-parametric correlation coefficient rho is used to investigate the possible relationships of different leadership styles with leadership outcomes.

Leadership outcomes show a large, positive, and statistically significant correlation with transformational leadership (r = 0.66, p < 0.01). This implies that a high degree of adoption of this leadership style coexists with effectiveness and satisfaction with leadership performance. Similarly, leadership outcomes also show a high, positive, and statistically significant correlation with transactional leadership (r = 0.39, p < 0.001). In contrast, a negative and statistically significant correlation is shown between leadership outcomes and passive–avoidant leadership (r = −0.29, p < 0.001). Therefore, the high degree of adoption of this style coexists with low levels of leadership effectiveness and satisfaction with leadership. If statistically significant correlations appear, there is a basis for the application of simple linear regression to determine whether there is a specific dependence of leadership outcome on each leadership style separately. The following regressions use leadership outcome as the dependent variable and each leadership style separately as the independent variable. The regression results are detailed in Table 12.

Table 12.

Correlation of leadership outcome with leadership styles.

Simple linear regression was used to examine the influence of each leadership style on leadership outcomes. The dependent variable was leadership outcome, while the independent variables were transformational leadership, transactional leadership, and passive–avoidant leadership. The results are presented in Table 13.

Table 13.

Dependence of leadership outcome on leadership styles.

Transformational leadership had a positive and statistically significant influence on leadership outcomes (β = 0.97, p < 0.001), suggesting that a higher adoption of this leadership style is associated with greater effectiveness and satisfaction. Transformational leadership also explained a substantial proportion of the variance in leadership outcomes (R2 = 0.586).

Transactional leadership also positively and significantly influenced leadership outcomes (β = 0.60, p < 0.001), indicating that it contributes to increased effectiveness and satisfaction, though to a lesser degree than transformational leadership. This variable accounted for 25.5% of the variance in leadership outcomes (R2 = 0.255).

In contrast, passive–avoidant leadership did not demonstrate a statistically significant effect on leadership outcomes (β = −0.18, p = 0.151), explaining only 2.0% of the variance (R2 = 0.020). These results reinforce the importance of adopting proactive leadership styles to enhance leadership effectiveness and satisfaction.

4.4. Relationship Between Digital Leadership and Leadership Styles

Spearman’s non-parametric correlation coefficient (r) was used to explore the relationships between digital leadership and different leadership styles. The results are presented in Table 14.

Table 14.

Correlation of digital leadership with leadership styles.

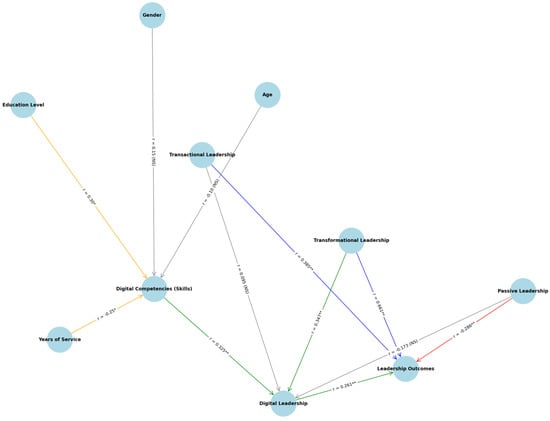

Digital leadership was positively and significantly correlated with transformational leadership (r = 0.35, p < 0.001), suggesting that a higher adoption of transformational leadership is associated with a greater degree of digital leadership. Similarly, digital leadership demonstrated a positive and statistically significant correlation with leadership outcomes (r = 0.26, p < 0.001), indicating that higher levels of leadership effectiveness and satisfaction are related to a greater adoption of digital leadership practices.

In contrast, transactional leadership (r = 0.10, p = 0.275) and passive–avoidant leadership (r = −0.17, p = 0.075) did not exhibit statistically significant correlations with digital leadership, highlighting that these styles may not strongly influence digital leadership behaviors.

Given the statistically significant correlations between digital leadership and transformational leadership, as well as leadership outcomes, simple linear regression was applied to determine whether digital leadership is specifically influenced by these factors. The results of the regression analyses are shown in Table 14.

Simple linear regression was conducted to examine the influence of different leadership styles on digital leadership. Digital leadership was used as the dependent variable, with transformational leadership, transactional leadership, and passive–avoidant leadership analyzed separately as independent variables. The results are summarized in Table 15. Transformational leadership had a positive and statistically significant effect on digital leadership (β = 0.72, p < 0.001), indicating that a higher adoption of transformational leadership is associated with greater digital leadership practices. This leadership style explained a substantial proportion of the variance in digital leadership (R2 = 0.271).

Table 15.

Dependence of digital leadership on leadership styles.

Transactional leadership also demonstrated a positive and statistically significant effect on digital leadership (β = 0.34, p = 0.006), suggesting that this style contributes to the ability to adopt and utilize digital capabilities. However, it explained a smaller proportion of the variance in digital leadership (R2 = 0.071). Passive–avoidant leadership did not exhibit a statistically significant effect on digital leadership (β = −0.09, p = 0.498), and it accounted for only a negligible portion of the variance (R2 = 0.004).

These findings emphasize the importance of the transformational and transactional leadership styles in fostering digital leadership practices while highlighting the limited role of passive–avoidant leadership in this context.

4.5. Necessary Digital Properties

The teachers who participated in the survey were asked to indicate the digital qualities that future principals should possess. Participants were able to choose one or more options.

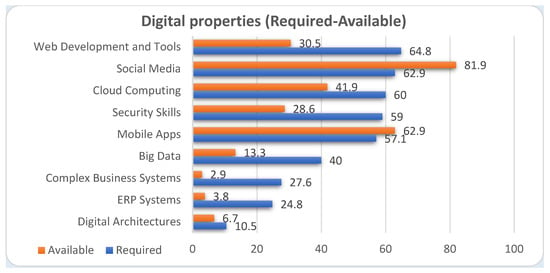

The digital properties Web Development and Tools, social media, and cloud computing are those with the highest response rates (64.8%, 62.9%, and 60.0%, respectively). However, most respondents also consider security skills (59.0%) and mobile apps (57.1%) important. Digital architectures (10.5%), ERP systems (24.8%), and complex business systems (27.6%) are the least often stated as being necessary digital qualities (Table 16).

Table 16.

Digital qualities that future managers must possess skills in.

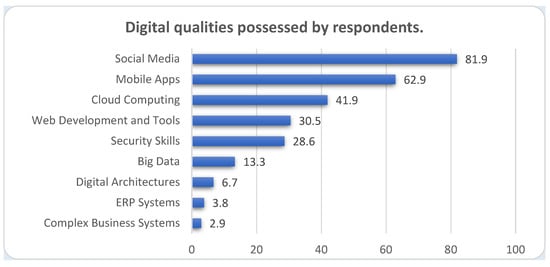

In terms of the digital attributes possessed by the respondents themselves, the highest percentages appear in social media (81.9%), mobile apps (62.9%), and cloud computing (41.9%). Digital architectures (6.7%), ERP systems (3.8%), and complex business systems (2.9%) are the digital attributes possessed the least by the survey participants (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Digital qualities possessed by respondents.

In order to compare the digital attributes stated as being necessary for future directors to have and the digital attributes possessed by the respondents, the following comparative bar chart is provided (Figure 2):

Figure 2.

Digital properties (Required–Available).

We note that social media and mobile apps are the only digital attributes that overlap in terms of those who possess them compared to those who reported them as being essential. Also, for the four most reported (as necessary) digital properties, they appear to be held by significantly smaller percentages of respondents (excluding social media). Alternatively, the number of digital attributes that survey participants reported to possess was examined.

On average, respondents reported to have about three of the nine attributes recorded. There were participants who reported having only one but also participants who reported having seven out of nine. To investigate whether demographic characteristics have a statistically significant effect on the number of digital properties held, non-parametric Mann–Whitney statistical tests were used (Table 17).

Table 17.

Number of digital properties.

The results show that “Specialty” is the only demographic characteristic that influences the number of digital properties possessed by respondents. Specifically, those holding the specialty of “Computer Science” reported holding a statistically significantly higher number of digital attributes (M = 5.17, SD = 1.94) compared to those holding other specialties. However, although the differences are not statistically significant, male participants, younger participants, those holding a Master’s or postgraduate degree, principals, and those serving in larger schools appear to possess more digital properties than their other colleagues. In addition, the relationship between different leadership styles and the number of digital attributes possessed by respondents was explored (Table 18).

Table 18.

Number of digital properties by demographic attribute.

The relationship between the number of digital attributes possessed by respondents and various leadership styles was examined using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. The results are summarized in Table 19.

Table 19.

Correlation of number of digital attributes with leadership styles.

The results indicate a positive and statistically significant correlation between the number of digital attributes held and the levels of digital leadership (r = 0.33, p < 0.001). This suggests that respondents possessing a higher number of digital attributes are more likely to exhibit higher levels of digital leadership. Correlations between the number of digital attributes and other leadership styles were not statistically significant.

To further analyze the data, the number of digital attributes was recorded as a qualitative variable, categorizing participants based on whether they possessed a few or many digital attributes. This transformation enabled a deeper understanding of the relationship between digital attributes and leadership styles.

Most respondents (72.4%) said they have a small number of digital properties (1–3) (Table 20).

Table 20.

Number of digital properties possessed by respondents.

The relationship between the number of digital attributes possessed by respondents and their levels of digital leadership was analyzed using a Mann–Whitney U test. The results are summarized in Table 21. Respondents with a high number of digital attributes (4–7) demonstrated significantly higher levels of digital leadership (M = 4.32, SD = 0.51) compared to those with a low number of attributes (1–3; M = 3.77, SD = 0.84). This difference was statistically significant (p = 0.001). These results indicate that possessing more digital attributes is strongly associated with higher digital leadership capabilities.

Table 21.

Levels of digital leadership by number of digital properties.

4.6. Behavioral Data Mining Analysis

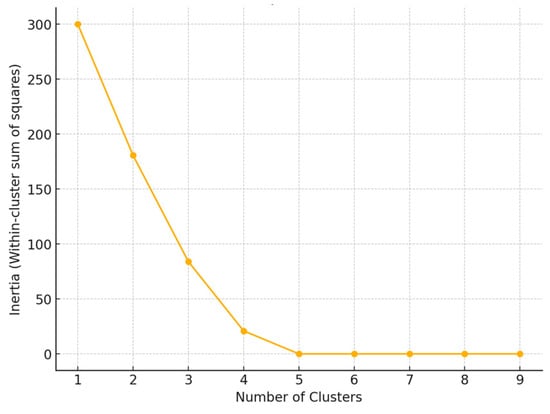

In this study, a behavioral data mining approach was applied to categorize leadership styles among primary school teachers in Western Greece. The objective was to identify distinct clusters of leadership behaviors and explore trends that could inform targeted development programs. Using K-means clustering, three clusters were identified based on teachers’ engagement in supportive actions, critical review, and non-intervention practices. To determine the optimal number of clusters, we applied the Elbow Method. This method involves calculating the within-cluster sum of squares (inertia) across a range of cluster counts and identifying the “elbow point” where adding more clusters yields diminishing returns. As shown in the visualization below (Figure 3), the curve flattens significantly after three clusters, indicating that three clusters sufficiently capture the major behavioral variations without unnecessary complexity. Consequently, three clusters were selected for the final analysis.

Figure 3.

Elbow Method of determining optimal number of clusters.

4.7. Summary of Leadership Clusters

Cluster 0, comprising 53% of the sample, was characterized by low engagement in supportive actions, critical review, and intervention. This passive approach suggests a tendency toward minimal proactive leadership behaviors. Most Cluster 0 members are teachers aged 41–50 with 11–20 years of experience. Their level of experience reflects a foundational understanding of their role, though development efforts could encourage greater engagement and responsibility. Cluster 1 represents 43% of the sample and includes leaders who show high levels of supportive behavior and moderate levels of critical review and who undertake a hands-on approach. These leaders are generally aged 51–60, with over 20 years of experience, which aligns with a supportive, experienced-based leadership style. However, the moderate level of critical review indicates that these leaders may benefit from developing adaptability and strategic thinking to balance their supportive tendencies with a broader perspective.

Cluster 2, the smallest group, representing only 4% of the sample, demonstrates a highly engaged leadership style with balanced behaviors across support, critical review, and non-intervention. This flexible and adaptable approach suggests a willingness to engage actively while allowing for autonomy within the team. Cluster 2 members are typically aged 51–60 and have 11–20 years of experience, showing that moderate experience paired with adaptability can lead to a balanced leadership style. This group may be particularly well suited for mentorship roles, sharing their proactive and flexible approach with peers (Table 22).

Table 22.

Table of clusters.

A further exploration of demographic trends reveals that age and experience significantly influence leadership styles. Clusters 1 and 2, composed of older, more experienced teachers, are generally more engaged and supportive, with Cluster 2 showing additional adaptability. Conversely, Cluster 0, which includes younger teachers with moderate experience, exhibits more passive leadership behaviors. This suggests that seasoned educators may gravitate toward more supportive and adaptive leadership, while less experienced teachers may benefit from targeted skill-building in proactive engagement and critical thinking.

Educational background remains largely uniform across clusters, with most teachers holding bachelor’s degrees. This uniformity implies that variations in leadership style are likely influenced more by professional experience and personal development than by academic qualifications. Since all clusters share a similar educational background, professional development efforts should prioritize skill-building in leadership behaviors rather than focusing on academic advancement. School size also plays a role, as most teachers across all clusters work in medium-sized schools with 6–12 classes. This setting fosters close interactions among staff, contributing to the strong supportive behaviors seen in Clusters 1 and 2. However, the supportive tendencies in these settings may also limit engagement in critical review, especially if routines are well established and change is infrequent. Leadership development initiatives in these environments could focus on enhancing management skills in terms of adaptability and change, ensuring that supportive behaviors are complemented by periodic critical evaluation.

The trends in critical review and non-intervention further highlight areas for development. Cluster 0 and Cluster 1 both display low engagement in critical review behaviors, suggesting that they may avoid challenging established practices in favor of stability. Cluster 2, however, balances support with critical review and autonomy, reflecting a more flexible, growth-oriented leadership style. This trend indicates that fostering critical review and adaptability in Clusters 0 and 1 could lead to a more balanced leadership culture.

Considering these findings, targeted professional development programs are recommended. Cluster 0 leaders could benefit from mentorship by Cluster 2 members, focusing on increasing engagement and supportive behaviors through small measurable goals and regular feedback. Cluster 1 leaders may benefit from workshops on critical thinking, situational leadership, and adaptability, allowing them to expand their supportive approach with a strategic perspective. For Cluster 2, mentorship and advanced leadership projects would enable them to share their flexible style with peers and apply their skills in broader organizational contexts. This behavioral data mining analysis provides valuable insights into the diverse leadership styles among primary school teachers. While supportive behaviors are prevalent across the sample, there is room to cultivate adaptability and critical review, particularly in Clusters 0 and 1. By implementing targeted training and mentorship, schools can develop a more engaged, adaptable, and proactive leadership team, ultimately enriching the educational environment.

5. Discussion

The present study attempted to investigate the leadership style that teachers in primary schools in the region of Western Greece apply or would apply if they were principals, as well as investigating their opinion on and their relationship with the digital skills that a digital school leader should possess. Regarding the demographic characteristics of the sample, most respondents are female teachers (81%), and most respondents are older than 40 years old. A total of 82.9% are permanent teachers, 39% have more than 20 years of experience, and most of them teach in 6–12/primary schools in the region of Western Greece. Finally, the largest percentage of the sample, as expected, are teachers; 61% have only a bachelor’s degree and no further education or postgraduate studies; and only 10.5% of them are or have been in a managerial position. Based on the results of this research, the research questions that were posed in the beginning were answered, as follows.

[RQ1]: What leadership style do primary school teachers apply or prefer in their professional roles, and how does it relate to digital leadership?

The leading styles therefore adopted or preferred by the teachers in primary schools are the transformational leadership style and the digital leadership style. Indeed, with the average scores of 4.10 and 3.92, respectively, both were adopted to a very large extent. These styles are then followed by the transactional style, with an average score of 3.68. By contrast, the passive–avoidant style of leadership is adopted to a minimal extent, as the average score is considerably lower, equating to 1.69. This clearly indicates that teachers prefer proactive and engaging styles of leadership as opposed to passive or non-interventionist approaches (Table 2). The findings also revealed that teachers view the transformational leadership style as highly effective; it is also the closest to the concept of digital leadership, encompassing innovation, collaboration, and adaptability related to digital transformation. It was therefore established that this kind of leadership plays a significant role in developing contexts that will support digital practices within primary education.

[RQ2]: How do demographic and professional characteristics influence the leadership styles adopted by primary school teachers?

The following are the key issues that arise from an examination of the leadership styles in relation to teachers’ demographic and professional characteristics: Overall, gender, age, and years of service are not determining factors in the kind of leadership style either adopted or preferred by teachers. Digital leadership seems to be more frequently adopted in the case of teachers with fewer years of service, perhaps because of their greater familiarity with digital tools and practices (Table 8). Teachers with postgraduate education are more likely to adopt transformational, digital, or transactional leadership styles, thus pointing out a significant difference from teachers who have only a basic degree. However, differences between these leadership styles are not statistically significant (Table 6). Permanent teachers are more likely to adopt transactional leadership; a larger percentage of permanent teachers also adopted passive leadership compared to their temporary peers (Table 7). Transformational leadership is more common in larger schools, which may reflect the fact that organizational complexity promotes the adoption of more dynamic and innovative approaches to school leadership. Neither the role of the principal nor teacher specialization is found to lead to any significant difference in terms of either leadership styles or outcomes, except for IT teachers, who show predictably higher levels of digital leadership (Table 11).

These findings also agree with research on higher education where demographic variables such as gender, age, and experience had similarly low effects on leadership styles. Curiously, older respondents in higher education showed lower adoption rates of digital leadership, consistent with this study’s observation of higher digital leadership among less experienced teachers. Across both contexts, increased teacher satisfaction is associated with a greater adoption of digital leadership. Importantly, this study identifies a strong, positive, and statistically significant relationship between transformational leadership and leadership outcomes (Table 12). Teachers who practice transformational leadership express higher satisfaction, irrespective of the grade level within which they operate (Table 13). As emphasized in the literature, the transformational type of leadership stimulates vision, inspiration, and a culture of more effort and efficiency, to which higher satisfaction and effectiveness are directly related. In contrast, passive leadership negatively impacts satisfaction and effectiveness, reinforcing the importance of adopting proactive leadership styles.

[RQ3]: What are the digital skills recognized and possessed by primary school teachers, and how do these skills support their role in digital leadership?

Regarding the digital skills of teachers, the survey identified notable gaps between the skills they consider necessary for digital leadership and those they currently possess. Teachers highlighted skills in Web Development and Tools (64.8%), social media (62.9%), and cloud computing (60%) as the most critical digital skills for school leadership. In contrast, the least important skills were identified as those in ERP systems, digital architectures, and complex business systems. Moreover, regarding their own digital competencies, teachers declared their highest proficiency in social media (81.9%), followed by mobile app use (62.9%) and cloud computing (41.9%). However, skills that are less common or more technical remain very low, such as those in ERP systems (3.8%) and digital architectures (6.7%). This gap shows a mismatch between the skills they have and those they consider important for digital leadership roles (Figure 2). It also emerges from the data that 72.4% of teachers have no more than one to three digital skills out of the nine shown, and only 29% have proficiencies in between four and seven digital skills. This therefore seems to suggest that most of the teachers have limited competencies, which might deter them from fully embracing or leading digital transformation for their schools. Additionally, the findings also identify that teachers with more digital skills have a significantly higher level of digital leadership. In this regard, it is underpinned that digital competencies are important in enabling teachers to engage in and lead digital practices effectively. The results represent the same findings as those found in prior higher education work: a large gap in digital skills between what exists within educators and what the requirements are for effective leadership within an institution. While other skills, such as those in social media and Web Development and Tools, consistently ranked high within various contexts, others, such as those in digital architectures and complex business systems, were underused despite their importance in a comprehensive digital leadership role. These findings pinpoint the necessity for focused professional development to enhance the digital skills of teachers, particularly in the areas of cloud computing, ERP systems, and digital architectures. This would help bridge the competency gap to better meet the demands required of teachers as digital leaders in primary education.

[RQ4]: Are teachers’ digital skills influenced by demographic and professional characteristics, such as age, gender, and educational background?