Examining the Influential Mechanism of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) Learners’ Flow Experiences in Digital Game-Based Vocabulary Learning: Shedding New Light on a Priori Proposed Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Digital Game-Based Vocabulary Learning

2.2. Digital Game-Based Vocabulary Learning and Flow Theory

2.3. Usage Frequency and Flow Experiences in Digital Game-Based Vocabulary Learning

2.4. Research on Chinese EFL Learners

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

3.2. Instrument

3.3. Data Collection and Analysis

4. Results

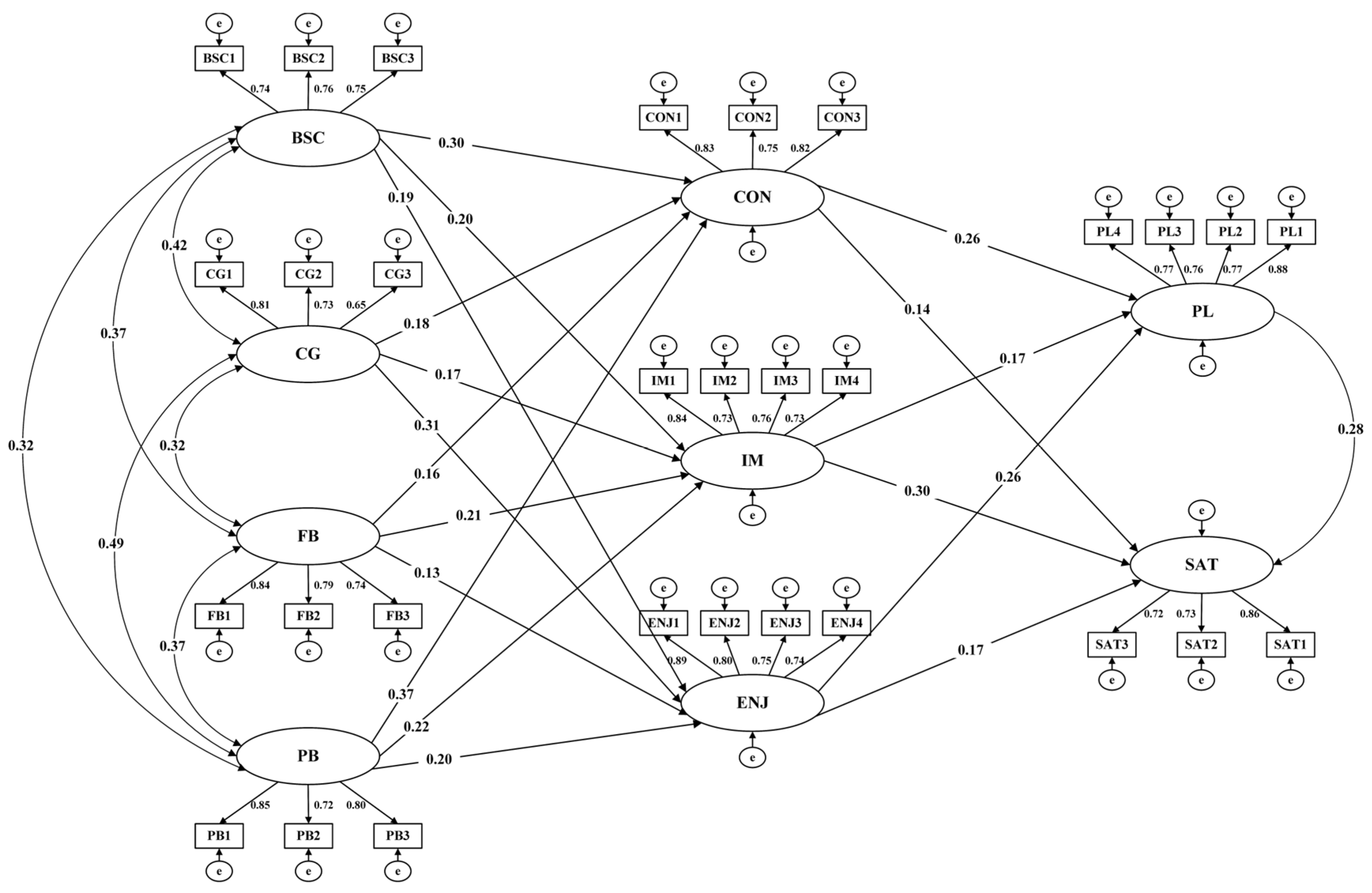

4.1. Measurement Model

4.2. Structural Model

4.3. Mediation Model Analysis

4.4. Multi-Group Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aydin, S. (2013). Teachers’ perceptions about the use of computers in EFL teaching and learning: The case of Turkey. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 26(3), 214–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashori, M., van Hout, R., Strik, H., & Cucchiarini, C. (2022). ‘Look, I can speak correctly’: Learning vocabulary and pronunciation through websites equipped with automatic speech recognition technology. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 37(5–6), 1335–1363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belda-Medina, J., & Calvo-Ferrer, J. (2022). Preservice teachers’ knowledge and attitudes toward digital-game-based language learning. Education Sciences, 12(3), 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blume, C. (2020). Games people (don’t) play: An analysis of pre-service EFL teachers’ behaviors and beliefs regarding digital game-based language learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 33(1–2), 109–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boers, F. (2022). Glossing and vocabulary learning. Language Teaching, 55(1), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyle, E., Hainey, T., Connolly, T., Gray, G., Earp, J., Ott, M., Lim, T., Ninaus, M., Ribeiro, C., & Pereira, J. (2016). An update to the systematic literature review of empirical evidence of the impacts and outcomes of computer games and serious games. Computers & Education, 94(1), 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buil, I., Catalan, S., & Martinez, E. (2018). Exploring students’ flow experiences in business simulation games. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 34(2), 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buil, I., Catalan, S., & Martinez, E. (2019). The influence of flow on learning outcomes: An empirical study on the use of clickers. British Journal of Educational Technology, 50(1), 428–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cervetti, G., Fitzgerald, M., Hiebert, E., & Hebert, M. (2023). Meta-analysis examining the impact of vocabulary instruction on vocabulary knowledge and skill. Reading Psychology, 44(6), 672–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, A., & Renandya, W. (2019). The effect of narrow reading on L2 learners’ vocabulary acquisition. RELC Journal, 52(3), 493–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G., Huang, Z., Wang, B., & Li, H. (1999). Flow regimes identification in horizontal pipe using wavelet transform. Chinese Journal of Scientific Instrument, 20(2), 117–120. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H., & Hsu, H. (2020). The impact of a serious game on vocabulary and content learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 33(7), 811–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M., Tseng, W., & Hsiao, T. (2018). The effectiveness of digital game-based vocabulary learning: A framework-based view of meta-analysis. British Journal of Educational Technology, 49(1), 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, K., Chang, C., & Lee, I. (2023). Vocabulary learning strategy instruction in the EFL secondary classroom: An exploratory study. Language Awareness, 32(1), 94–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb, T., & Laufer, B. (2021). The nuclear word family list: A list of the most frequent family members, including base and affixed words. Language Learning, 71(3), 834–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1975). Beyond freedom and boredom. Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1991). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. American Journal of Psychotherapy, 45(1), 142–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, T. N. Y., Lu, C., & Webb, S. (2022). Open access academic lectures as sources for incidental vocabulary learning: Examining the role of input mode, frequency, type of vocabulary, and elaboration. Applied Linguistics, 44(4), 747–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, E., & Hong, G. (2022). Engagement mediates the relationship between emotion and achievement of Chinese EFL learners. Frontiers in Psychology, 13(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroutan Far, F., & Taghizadeh, M. (2022). Comparing the effects of digital and non-digital gamification on EFL learners’ collocation knowledge, perceptions, and sense of flow. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 37(7), 2083–2115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y., & Pan, L. (2023). Learning English vocabulary through playing games: The gamification design of vocabulary learning applications and learner evaluations. The Language Learning Journal, 51(4), 451–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle, R. H., & Panter, A. T. (1995). Writing about structural equation models. In R. Hoyle (Ed.), Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications (pp. 158–176). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, C., Sun, J., & Yu, P. (2015). The benefits of a challenge: Student motivation and flow experience in tablet-PC-game-based learning. Interactive Learning Environments, 23(2), 172–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, H., Yang, J., Hwang, G., Chu, H., & Wang, C. (2018). A scoping review of research on digital game-based language learning. Computers & Education, 126(1), 89–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, G., & Wang, S. (2016). Single loop or double loop learning: English vocabulary learning performance and behavior of students in situated computer games with different guiding strategies. Computers & Education, 102(1), 188–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iravi, Y., & Malmir, A. (2023). The effect of lexical tools and applications on L2 vocabulary learning: A case of English academic core words. Innovation In Language Learning and Teaching, 17(3), 636–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, C., & Cadierno, T. (2022). Differences in mobile-assisted acquisition of receptive and productive vocabulary knowledge: A case study using Mondly. The Language Learning Journal, 52(3), 255–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joo, Y., Lim, K., & Su, Y. (2011). Investigating the structural relationships among organizational support, learning flow, learners’ satisfaction and learning transfer in corporate e-learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 42(6), 973–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamis, A., Stern, T., & Ladik, D. (2010). A flow-based model of web site intentions when users customize products in business-to-consumer electronic commerce. Information Systems Frontiers, 12(2), 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazu, İ., & Kuvvetli, M. (2023). A triangulation method on the effectiveness of digital game-based language learning for vocabulary acquisition. Education and Information Technologies, 28(10), 13541–13567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kiili, K., Lainema, T., Freitas, S. D., & Arnab, S. (2014). Flow framework for analyzing the quality of educational games. Entertainment Computing, 5(4), 367–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, K., & Chen, H. (2023). A comparative study on the effects of a VR and PC visual novel game on vocabulary learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 36(3), 312–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laufer, B., & Rozovski-Roitblat, B. (2011). Incidental vocabulary acquisition: The effects of task type, word occurrence and their combination. Language Teaching Research, 15(4), 391–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, S. K. Y., & Choi, K. W. Y. (2024). Teachers’ perceptions of technical affordances in early visual arts education. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 32(1), 147–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C. (2024). A review of theories, pedagogies and vocabulary learning tasks of English vocabulary learning apps for Chinese EFL learners. Journal of China Computer-Assisted Language Learning, 4(2), 346–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R. (2021). Does game-based vocabulary learning APP influence Chinese EFL learners’ vocabulary achievement, motivation, and self-confidence? Sage Open, 11(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R., Meng, Z., Tian, M., Zhang, Z., & Xiao, W. (2021). Modelling Chinese EFL learners’ flow experiences in digital game-based vocabulary learning: The roles of learner and contextual factors. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 34(4), 483–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R. (2015). On the need for research evidence to guide the design of computer games for learning. Educational Psychologist, 50(4), 349–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nation, P. (2001). Learning vocabulary in another language. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nation, P. (2021). Is it worth teaching vocabulary? TESOL Journal, 12(4), 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellicer-Sánchez, A., Conklin, K., & Vilkaitė-Lozdienė, L. (2021). The effect of pre-reading instruction on vocabulary learning: An investigation of L1 and L2 readers’ eye movements. Language Learning, 71(1), 162–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellicer-Sánchez, A., Siyanova-Chanturia, A., & Parente, F. (2022). The effect of frequency of exposure on the processing and learning of collocations: A comparison of first and second language readers’ eye movements. Applied Psycholinguistics, 43(3), 727–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, M. (2023). Digital simulation games in CALL: A research review. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 36(5–6), 943–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raeisi-Vanani, A., & Baleghizadeh, S. (2022). The contributory role of grammar vs. vocabulary in L2 reading: An SEM approach. Foreign Language Annals, 55(2), 559–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasti-Behbahani, A., & Shahbazi, M. (2022). Investigating the effectiveness of a digital game-based task on the acquisition of word knowledge. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 35(8), 1920–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, B. (2017). Evidence for the task-induced involvement construct in incidental vocabulary acquisition through digital gaming. The Language Learning Journal, 45(4), 466–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, B. (2020). The effects of nonce words, frequency, contextual richness, and L2 vocabulary knowledge on the incidental acquisition of vocabulary through reading: More than a replication of Zahar et al. (2001) & Tekmen and Daloğlu (2006). International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 58(1), 75–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, N. (2014). Size and depth of vocabulary knowledge: What the research shows. Language Learning, 64(4), 913–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, N. (2006). Online learner’s ‘flow’ experience: An empirical study. British Journal of Educational Technology, 37(5), 705–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soyoof, A., Reynolds, B., Shadiev, R., & Vazquez-Calvo, B. (2024). A mixed-methods study of the incidental acquisition of foreign language vocabulary and healthcare knowledge through serious game play. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 37(1–2), 27–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J., Gyllstad, H., Nicklin, C., & McLean, S. (2024). Establishing meaning recall and meaning recognition vocabulary knowledge as distinct psychometric constructs in relation to reading proficiency. Language Testing, 41(1), 89–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundqvist, P., & Wikström, P. (2015). Out-of-school digital gameplay and in-school L2 English vocabulary outcomes. System, 51(1), 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, T., Chen, H., & Todd, G. (2022). The impact of a virtual reality app on adolescent EFL learners’ vocabulary learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 35(4), 892–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, M. F., & Zhang, D. (2024). Task-induced involvement load, vocabulary learning in a foreign language, and their association with metacognition. Language Teaching Research, 28(2), 531–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, Y., & Tsai, C. (2018). Digital game-based second-language vocabulary learning and conditions of research designs: A meta-analysis study. Computers & Education, 125(1), 345–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchihara, T., & Clenton, J. (2023). The role of spoken vocabulary knowledge in second language speaking proficiency. The Language Learning Journal, 51(3), 376–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchihara, T., Webb, S., & Yanagisawa, A. (2019). The effects of repetition on incidental vocabulary learning: A meta-analysis of correlational studies. Language Learning, 69(1), 559–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vnucko, G., & Klimova, B. (2023). Exploring the potential of digital game-based vocabulary learning: A systematic review. Systems, 11(2), 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, S., & Nation, P. (2017). How vocabulary is learned. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Woody, E. (2011). An SEM perspective on evaluating mediation: What every clinical researcher needs to know. Journal of Experimental Psychopathology, 2(2), 210–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, Y. (2014). Multidimensional vocabulary acquisition through deliberate vocabulary list learning. System, 42(1), 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagisawa, A., & Webb, S. (2021). To what extent does the involvement load hypothesis predict incidental L2 vocabulary learning? A meta-analysis. Language Learning, 71(2), 487–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J., Chung, C., & Chen, M. (2022). Effects of performance goal orientations on learning performance and in-game performance in digital game-based learning. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 38(2), 422–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q., Chang, S., Hwang, G., & Zou, D. (2020). Balancing cognitive complexity and gaming level: Effects of a cognitive complexity-based competition game on EFL students’ English vocabulary learning performance, anxiety and behaviors. Computers & Education, 148(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., Lee, I., Tseng, C., & Lai, S. (2024). Developing students’ self-regulated learning strategies to facilitate vocabulary development in a digital game-based learning environment. Journal of Research on Technology in Education. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeldham, M. (2023). Second language listening instruction and learners’ vocabulary knowledge. International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 61(3), 819–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R., Zou, D., & Cheng, G. (2023). Learner engagement in digital game-based vocabulary learning and its effects on EFL vocabulary development. System, 119, 103173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R., Zou, D., & Cheng, G. (2024a). Behavioural engagement with notes and note content in digital game-based vocabulary learning and their effects on EFL vocabulary development. Innovation in language learning and teaching. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R., Zou, D., & Cheng, G. (2024b). Self-regulated digital game-based vocabulary learning: Motivation, application of self-regulated learning strategies, EFL vocabulary knowledge development, and their interplay. Computer assisted language learning. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, D., Huang, Y., & Xie, H. (2021). Digital game-based vocabulary learning: Where are we and where are we going? Computer Assisted Language Learning, 34(5/8), 751–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Flow Factors | Constructs | Questionnaire Items | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flow antecedents | Learner factors | Balance of skill and challenge (BSC) | I believed my skills would allow me to meet the challenge in the DGBVL. I considered the challenge of the DGBVL and my skills to be at an equally high level. I felt I was competent enough to meet the high challenging demands of the DGBVL. |

| Clear goal (CG) | When I am learning vocabularies with the DGBVL, the goals were clearly defined. When I am learning vocabularies with the DGBVL, I knew what I had to do. When I am learning vocabularies with the DGBVL, I knew what I had to achieve. | ||

| Contextual factors | Feedback (FB) | While I am learning vocabularies with the DGBVL, I receive feedback about the learning progress. While I am learning vocabularies with the DGBVL, I am notified about the results of my decision-making. While I am learning vocabularies with the DGBVL, I receive information on my score of performance. | |

| Playability (PB) | The rules, goals and design of DGBVL are clear and easy to follow. The graphic design and interactive scenes of DGBVL are smooth. The user interface and game control are of high quality. | ||

| Flow contents | Concentration (CON) | I can completely focus on learning vocabularies with the DGBVL. My attention was focused entirely on what I was doing with the DGBVL. When I am learning vocabularies with the DGBVL, I am totally immersed in it and forget everything else around me. | |

| Intrinsic motivation (IM) | I would still learn vocabularies with the DGBVL, even if I was not rewarded instantly for it. I also want to learn vocabularies with the DGBVL in my free time. I learn vocabularies with the DGBVL because I enjoy it. I get my motivation from learning vocabularies with the DGBVL, and not from the benefits I can obtain by using it. | ||

| Enjoyment (ENJ) | Learning vocabularies with the DGBVL gives me a good feeling. I get a lot of enjoyment from learning vocabularies with the DGBVL. I feel happy while learning vocabularies with the DGBVL. I feel cheerful when I learn vocabularies with the DGBVL. | ||

| Flow outcomes | Perceived learning (PL) | The DGBVL was useful for my vocabulary learning. The DGBVL helped me learn vocabularies well. The DGBVL facilitated my understanding of vocabulary usages during vocabulary learning. My stock of vocabularies was enlarged with the use of DGBVL. | |

| Satisfaction (SAT) | I found learning vocabularies with the DGBVL valuable. I was very satisfied with learning vocabularies with the DGBVL. I had a very positive learning experience during learning vocabularies with the DGBVL. | ||

| Factor | Item | Standard Loading | CR | AVE | Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSC | BSC1 BSC2 BSC3 | 0.746 0.764 0.748 | 0.797 | 0.567 | 0.797 |

| CG | CG1 CG2 CG3 | 0.816 0.726 0.647 | 0.775 | 0.537 | 0.767 |

| FB | FB1 FB2 FB3 | 0.836 0.787 0.735 | 0.830 | 0.620 | 0.826 |

| PB | PB1 PB2 PB3 | 0.849 0.720 0.802 | 0.834 | 0.628 | 0.830 |

| CON | CON1 CON2 CON3 | 0.832 0.751 0.817 | 0.843 | 0.641 | 0.839 |

| IM | IM1 IM2 IM3 IM4 | 0.833 0.736 0.759 0.731 | 0.850 | 0.587 | 0.846 |

| ENJ | ENJ1 ENJ2 ENJ3 ENJ4 | 0.887 0.801 0.749 0.739 | 0.873 | 0.634 | 0.868 |

| SAT | SAT1 SAT2 SAT3 | 0.862 0.732 0.727 | 0.819 | 0.623 | 0.807 |

| PL | PL1 PL2 PL3 PL4 | 0.882 0.775 0.760 0.776 | 0.876 | 0.640 | 0.873 |

| BSC | CG | FB | PB | CON | IM | ENJ | SAT | PL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSC | 0.753 | ||||||||

| CG | 0.416 *** | 0.733 | |||||||

| FB | 0.370 *** | 0.317 *** | 0.787 | ||||||

| PB | 0.320 *** | 0.485 *** | 0.370 *** | 0.792 | |||||

| CON | 0.487 *** | 0.438 *** | 0.387 *** | 0.421 *** | 0.801 | ||||

| IM | 0.396 *** | 0.407 *** | 0.403 *** | 0.430 *** | 0.502 *** | 0.766 | |||

| ENJ | 0.425 *** | 0.517 *** | 0.364 *** | 0.453 *** | 0.334 *** | 0.388 *** | 0.796 | ||

| SAT | 0.361 *** | 0.381 *** | 0.408 *** | 0.373 *** | 0.450 *** | 0.532 *** | 0.443 *** | 0.789 | |

| PL | 0.314 *** | 0.356 *** | 0.324 *** | 0.265 *** | 0.429 *** | 0.393 *** | 0.521 *** | 0.415 *** | 0.800 |

| Path | b | β | SE | C.R. | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSC→CON | 0.371 | 0.303 | 0.091 | 4.083 | <0.001 |

| BSC→IM | 0.237 | 0.197 | 0.088 | 2.698 | 0.007 |

| BSC→ENJ | 0.238 | 0.187 | 0.089 | 2.687 | 0.007 |

| CG→CON | 0.209 | 0.181 | 0.089 | 2.334 | 0.020 |

| CG→IM | 0.190 | 0.168 | 0.088 | 2.153 | 0.031 |

| CG→ENJ | 0.365 | 0.306 | 0.091 | 3.985 | <0.001 |

| FB→CON | 0.167 | 0.164 | 0.069 | 2.407 | 0.016 |

| FB→IM | 0.211 | 0.211 | 0.069 | 3.052 | 0.002 |

| FB→ENJ | 0.137 | 0.130 | 0.069 | 1.987 | 0.047 |

| PB→CON | 0.194 | 0.181 | 0.078 | 2.477 | 0.013 |

| PB→IM | 0.227 | 0.216 | 0.078 | 2.925 | 0.003 |

| PB→ENJ | 0.219 | 0.198 | 0.078 | 2.797 | 0.005 |

| CON→PL | 0.271 | 0.263 | 0.069 | 3.900 | <0.001 |

| CON→SAT | 0.130 | 0.140 | 0.062 | 2.101 | 0.036 |

| IM→PL | 0.180 | 0.171 | 0.069 | 2.611 | 0.009 |

| IM→SAT | 0.286 | 0.300 | 0.062 | 4.612 | <0.001 |

| ENJ→PL | 0.262 | 0.264 | 0.065 | 4.037 | <0.001 |

| ENJ→SAT | 0.156 | 0.173 | 0.058 | 2.672 | 0.008 |

| PL→SAT | 0.250 | 0.275 | 0.061 | 4.089 | <0.001 |

| β | p | [95% CI] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor variable: BSC | |||

| Total indirect | 0.179 | 0.001 | [0.079, 0.278] |

| BSC→CON→PL→SAT | 0.022 | 0.001 | [0.007, 0.053] |

| BSC→CON→SAT | 0.042 | 0.019 | [0.006, 0.097] |

| BSC→IM→PL→SAT | 0.009 | 0.017 | [0.001, 0.031] |

| BSC→IM→SAT | 0.059 | 0.015 | [0.013, 0.131] |

| BSC→ENJ→PL→SAT | 0.014 | 0.009 | [0.003, 0.037] |

| BSC→ENJ→SAT | 0.032 | 0.018 | [0.005, 0.079] |

| Predictor variable: CG | |||

| Total indirect | 0.172 | 0.003 | [0.068, 0.278] |

| CG→CON→PL→SAT | 0.013 | 0.030 | [0.001, 0.040] |

| CG→CON→SAT | 0.025 | 0.046 | [0.000, 0.078] |

| CG→IM→PL→SAT | 0.008 | 0.045 | [0.000, 0.030] |

| CG→IM→SAT | 0.051 | 0.062 | [−0.003, 0.126] |

| CG→ENJ→PL→SAT | 0.022 | <0.001 | [0.008, 0.053] |

| CG→ENJ→SAT | 0.053 | 0.005 | [0.015, 0.116] |

| Predictor variable: FB | |||

| Total indirect | 0.140 | 0.002 | [0.056, 0.221] |

| FB→CON→PL→SAT | 0.012 | 0.020 | [0.001, 0.034] |

| FB→CON→SAT | 0.023 | 0.038 | [0.001, 0.068] |

| FB→IM→PL→SAT | 0.010 | 0.011 | [0.002, 0.033] |

| FB→IM→SAT | 0.063 | 0.006 | [0.016, 0.138] |

| FB→ENJ→PL→SAT | 0.009 | 0.026 | [0.001, 0.029] |

| FB→ENJ→SAT | 0.022 | 0.040 | [0.001, 0.067] |

| Predictor variable: PB | |||

| Total indirect | 0.162 | 0.001 | [0.075, 0.252] |

| PB→CON→PL→SAT | 0.013 | 0.010 | [0.003, 0.034] |

| PB→CON→SAT | 0.025 | 0.028 | [0.002, 0.074] |

| PB→IM→PL→SAT | 0.010 | 0.012 | [0.002, 0.030] |

| PB→IM→SAT | 0.065 | 0.007 | [0.016, 0.133] |

| PB→ENJ→PL→SAT | 0.014 | 0.001 | [0.004, 0.035] |

| PB→ENJ→SAT | 0.034 | 0.007 | [0.007, 0.082] |

| Path | B | χ2 | Δχ2 | p Value for Δχ2 | Post Hoc Comparison | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Seldom (N = 78) | 2 Sometimes (N = 103) | 3 Always (N = 125) | |||||

| BSC→CON | |||||||

| bs equal for all | 0.402 *** | 0.402 *** | 0.402 *** | 1374.859 | 2.991 | 0.224 | - |

| bs free to differ | 0.764 * | 0.477 ** | 0.245 | 1371.868 | |||

| BSC→IM | |||||||

| bs equal for all | 0.225 * | 0.225 * | 0.225 * | 1373.673 | 1.805 | 0.406 | - |

| bs free to differ | 0.364 | 0.073 | 0.319 * | 1371.868 | |||

| BSC→ENJ | |||||||

| bs equal for all | 0.312 *** | 0.312 *** | 0.312 *** | 1382.282 | 10.414 ** | 0.005 | 1 = 2 > 3 |

| bs free to differ | 0.514 | 0.734 *** | 0.104 | 1371.868 | |||

| CG→CON | |||||||

| bs equal for all | 0.184 * | 0.184 * | 0.184 * | 1376.275 | 4.407 | 0.110 | - |

| bs free to differ | 0.120 | 0.006 | 0.424 ** | 1371.868 | |||

| CG→IM | |||||||

| bs equal for all | 0.197 * | 0.197 * | 0.197 * | 1373.330 | 1.462 | 0.481 | - |

| bs free to differ | 0.218 | 0.089 | 0.328 * | 1371.868 | |||

| CG→ENJ | |||||||

| bs equal for all | 0.307 *** | 0.307 *** | 0.307 *** | 1375.107 | 3.238 | 0.198 | - |

| bs free to differ | 0.384 * | 0.065 | 0.400 *** | 1371.868 | |||

| FB→CON | |||||||

| bs equal for all | 0.153 * | 0.153 * | 0.153 * | 1372.775 | 0.907 | 0.635 | - |

| bs free to differ | −0.018 | 0.186 | 0.177 | 1371.868 | |||

| FB→IM | |||||||

| bs equal for all | 0.230 *** | 0.230 *** | 0.230 *** | 1376.465 | 4.597 | 0.100 | - |

| bs free to differ | −0.068 | 0.407 ** | 0.185 | 1371.868 | |||

| FB→ENJ | |||||||

| bs equal for all | 0.109 | 0.109 | 0.109 | 1371.993 | 0.125 | 0.939 | - |

| bs free to differ | 0.057 | 0.140 | 0.108 | 1371.868 | |||

| PB→CON | |||||||

| bs equal for all | 0.220 ** | 0.220 ** | 0.220 ** | 1376.146 | 4.278 | 0.118 | - |

| bs free to differ | 0.103 | 0.416 ** | 0.059 | 1371.868 | |||

| PB→IM | |||||||

| bs equal for all | 0.204 ** | 0.204 ** | 0.204 ** | 1372.771 | 0.903 | 0.637 | - |

| bs free to differ | 0.312 * | 0.201 | 0.112 | 1371.868 | |||

| PB→ENJ | |||||||

| bs equal for all | 0.184 * | 0.184 * | 0.184 * | 1374.444 | 2.576 | 0.276 | - |

| bs free to differ | 0.076 | 0.354 ** | 0.119 | 1371.868 | |||

| CON→PL | |||||||

| bs equal for all | 0.252 * | 0.252 * | 0.252 * | 1376.650 | 4.782 | 0.092 | - |

| bs free to differ | 0.302 ** | 0.008 | 0.396 *** | 1371.868 | |||

| CON→SAT | |||||||

| bs equal for all | 0.141 * | 0.141 * | 0.141 * | 1375.350 | 3.482 | 0.175 | - |

| bs free to differ | −0.006 | 0.118 | 0.304 ** | 1371.868 | |||

| IM→SAT | |||||||

| bs equal for all | 0.316 *** | 0.316 *** | 0.316 *** | 1374.563 | 2.695 | 0.260 | - |

| bs free to differ | 0.253 ** | 0.477 *** | 0.236 * | 1371.868 | |||

| IM→PL | |||||||

| bs equal for all | 0.142 * | 0.142 * | 0.142 * | 1373.673 | 1.268 | 0.530 | - |

| bs free to differ | 0.030 | 0.220 | 0.190 | 1371.868 | |||

| ENJ→PL | |||||||

| bs equal for all | 0.307 *** | 0.307 *** | 0.307 *** | 1374.356 | 2.487 | 0.288 | - |

| bs free to differ | 0.170 | 0.431 *** | 0.257 | 1371.868 | |||

| ENJ→SAT | |||||||

| bs equal for all | 0.095 * | 0.095 * | 0.095 * | 1384.106 | 12.238 ** | 0.002 | 1 = 2 < 3 |

| bs free to differ | 0.079 | −0.089 | 0.469 *** | 1371.868 | |||

| PL→SAT | |||||||

| bs equal for all | 0.298 *** | 0.298 *** | 0.298 *** | 1387.887 | 16.019 *** | <0.001 | 1 = 2 > 3 |

| bs free to differ | 0.392 ** | 0.517 *** | −0.034 | 1371.868 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, X.; Feng, L. Examining the Influential Mechanism of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) Learners’ Flow Experiences in Digital Game-Based Vocabulary Learning: Shedding New Light on a Priori Proposed Model. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15020125

Wang X, Feng L. Examining the Influential Mechanism of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) Learners’ Flow Experiences in Digital Game-Based Vocabulary Learning: Shedding New Light on a Priori Proposed Model. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(2):125. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15020125

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xuan, and Linfei Feng. 2025. "Examining the Influential Mechanism of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) Learners’ Flow Experiences in Digital Game-Based Vocabulary Learning: Shedding New Light on a Priori Proposed Model" Education Sciences 15, no. 2: 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15020125

APA StyleWang, X., & Feng, L. (2025). Examining the Influential Mechanism of English as a Foreign Language (EFL) Learners’ Flow Experiences in Digital Game-Based Vocabulary Learning: Shedding New Light on a Priori Proposed Model. Education Sciences, 15(2), 125. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15020125