Family vs. Teacher–Student Relationships and Online Learning Outcomes Among Chinese University Students: Evidence from the Pandemic Period

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. The Direct Associations of Family and Teacher–Student Relationships

1.2. The Mediating Role of Self-Efficacy

1.3. Our Study

- Both family and teacher–student relationships are positively associated with online learning outcomes;

- Self-efficacy mediates the positive associations between both family and teacher–student relationships and online learning outcomes;

- The overall effect sizes of family and teacher–student relationships with online learning outcomes do not differ significantly;

- The indirect effect sizes via self-efficacy are greater for teacher–student relationships than for family relationships.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Measurements

2.3. Common Method Bias

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Description and Correlation

3.2. Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analyses

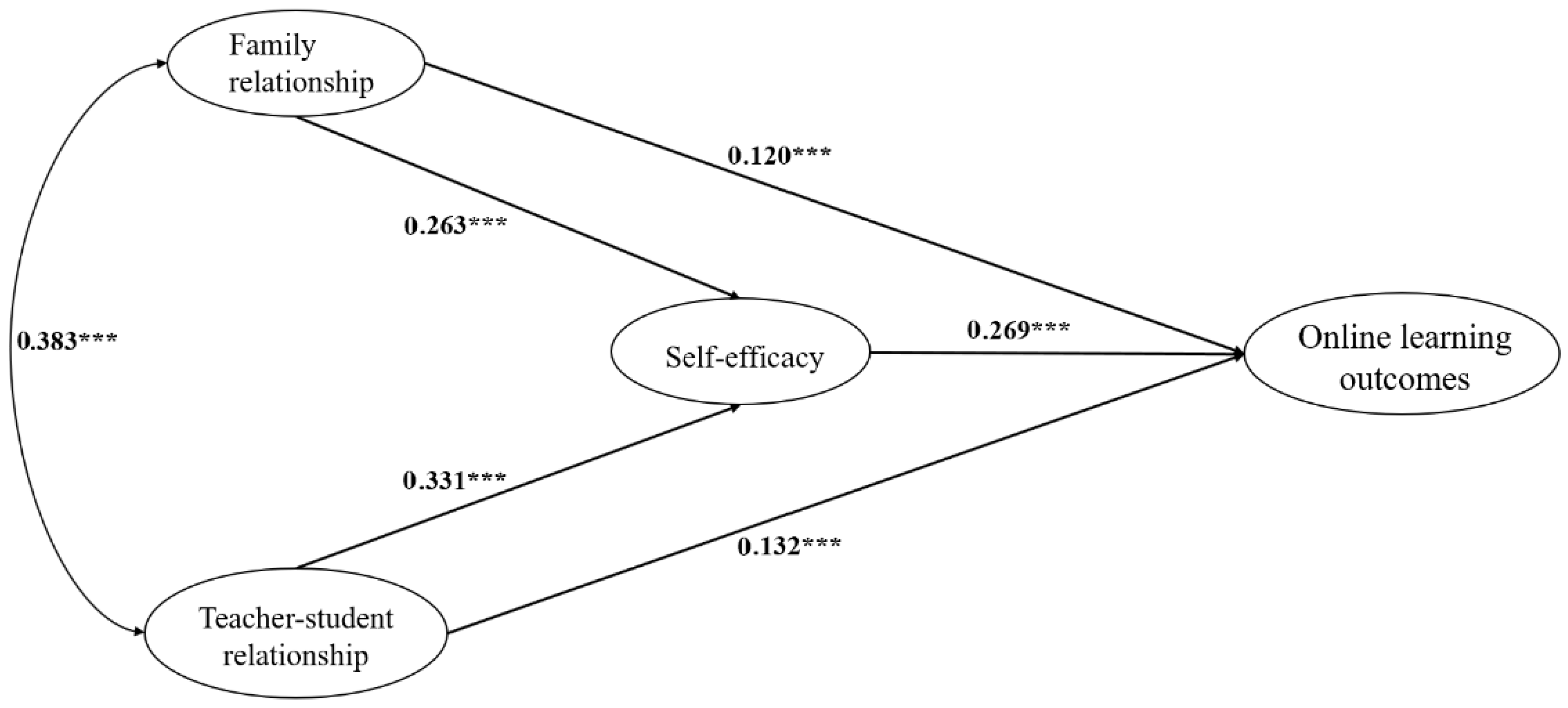

3.3. Examination of the Mediation Model

4. Discussion

4.1. The Total Effects of Family Relationship and Teacher–Student Relationship

4.2. The Stronger Indirect Effect of Teacher–Student Relationship

4.3. Limitations

4.4. Practical Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Item | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Factor 4 |

| Factor 1: Online learning outcomes, original root = 5.403, Rotated variance explained = 17.777 | ||||

| OLO1 | 0.753 | |||

| OLO2 | 0.848 | |||

| OLO3 | 0.850 | |||

| OLO4 | 0.653 | |||

| OLO5 | 0.752 | |||

| Factor 2: Family relationship, original root = 1.885, Rotated variance explained = 12.961 | ||||

| FR1 | 0.772 | |||

| FR2 | 0.730 | |||

| FR3 | 0.790 | |||

| FR4 | 0.738 | |||

| Factor 3: Teacher–student relationship, original root = 1.615, Rotated variance explained = 12.223 | ||||

| TSR1 | 0.660 | |||

| TSR2 | 0.670 | |||

| TSR3 | 0.771 | |||

| TSR4 | 0.770 | |||

| TSR5 | 0.774 | |||

| TSR6 | 0.716 | |||

| Factor 4: Self-efficacy, original root =2.404, Rotated variance explained = 16.546 | ||||

| SE1 | 0.737 | |||

| SE2 | 0.787 | |||

| SE3 | 0.706 | |||

| SE4 | 0.688 | |||

| Latent Factors | Items | Std. Error | CR | Std. Estimate | AVE | CR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Online learning outcomes | OLO1 | - | - | 0.706 | 0.541 | 0.852 |

| OLO2 | 0.037 | 26.136 | 0.671 | |||

| OLO3 | 0.037 | 22.522 | 0.575 | |||

| OLO4 | 0.037 | 32.197 | 0.849 | |||

| OLO5 | 0.037 | 31.979 | 0.841 | |||

| Self-efficacy | SE1 | - | - | 0.610 | 0.440 | 0.758 |

| SE2 | 0.055 | 20.909 | 0.694 | |||

| SE3 | 0.057 | 20.867 | 0.692 | |||

| SE4 | 0.052 | 20.244 | 0.656 | |||

| Family relationship | FR1 | - | - | 0.727 | 0.482 | 0.788 |

| FR2 | 0.037 | 24.937 | 0.707 | |||

| FR3 | 0.042 | 24.989 | 0.709 | |||

| FR4 | 0.040 | 22.786 | 0.630 | |||

| Teacher–student relationship | TSR1 | - | - | 0.584 | 0.476 | 0.843 |

| TSR2 | 0.051 | 21.658 | 0.668 | |||

| TSR3 | 0.054 | 23.296 | 0.749 | |||

| TSR4 | 0.056 | 23.399 | 0.754 | |||

| TSR5 | 0.049 | 19.991 | 0.595 | |||

| TSR6 | 0.055 | 23.576 | 0.764 |

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Teacher–student relationship | 0.690 a | |||

| 2. Family relationship | 0.317 | 0.694 a | ||

| 3. Self-efficacy | 0.356 | 0.301 | 0.664 a | |

| 4. Online learning outcomes | 0.267 | 0.238 | 0.313 | 0.736 a |

- Family relationship:

- Family members ask each other for help when needed.

- The relationships between family members and their friends are closer than those among other family members.

- Family members are familiar with each other’s close friends.

- When conflicts arise in the family, members show mutual concession to reach a compromise.

- Teacher–student relationship:

- My teacher doesn’t get upset when I disagree with them.

- The teacher treats us as equals during the teaching process.

- I can easily contact teachers who have previously taught me.

- I can easily approach teachers and ask them questions.

- The teacher allocates sufficient time for interaction and communication with me.

- When I send messages to the teacher, I receive a prompt response.

- Self-efficacy:

- I can always solve my problem if I try my best.

- Even when others oppose me, I can still achieve what I want.

- For me, pursuing my ideals and achieving my goals is easy.

- I am confident in my ability to effectively handle any unexpected events.

- Online learning outcomes:

- After learning online, I’ve become way more independent.

- After learning online, my knowledge has broadened.

- After learning online, my way of thinking has become more mature.

- After learning online, I feel my personal arrangements are more flexible.

- After learning online, my practical skills have noticeably improved.

References

- Alrabai, F., & Algazzaz, W. (2025). Testing experimental-based models on the influence of teacher emotional support on students’ basic psychological needs, emotions, and emotional engagement. Applied Linguistics, amaf036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37(2), 122–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, A. A., Domenech Rodríguez, M. M., Wieling, E., Parra-Cardona, J. R., Rains, L. A., & Forgatch, M. S. (2019). Teaching GenerationPMTO, an evidence-based parent intervention, in a university setting using a blended learning strategy. Pilot and Feasibility Studies, 5(1), 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benner, A. D., Fernandez, C. C., Hou, Y., & Gonzalez, C. S. (2021). Parent and teacher educational expectations and adolescents’ academic performance: Mechanisms of influence. Journal of Community Psychology, 49(7), 2679–2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bol, T., Witschge, J., Van de Werfhorst, H. G., & Dronkers, J. (2014). Curricular tracking and central examinations: Counterbalancing the impact of social background on student achievement in 36 countries. Social Forces, 94(4), 1545–1572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (2005). Making human beings human: Bioecological perspectives on human development. SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Brouwers, M. C., Makarski, J., & Levinson, A. J. (2010). A randomized trial to evaluate e-learning interventions designed to improve learner’s performance, satisfaction, and self-efficacy with the AGREE II. Implementation Science, 5, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, L., Mak, M. C., Li, T., Wu, B. P., Chen, B. B., & Lu, H. J. (2011). Cultural adaptations to environmental variability: An evolutionary account of East–West differences. Educational Psychology Review, 23(1), 99–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B. B., Wiium, N., Dimitrova, R., & Chen, N. (2019). The relationships between family, school and community support and boundaries and student engagement among Chinese adolescents. Current Psychology, 38(3), 705–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W., Ickes, W., & Verhofstadt, L. (2012). How is family support related to students’ GPA scores? A longitudinal study. Higher Education, 64(3), 399–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC). (2025). Statistical report on internet development in China. Available online: https://www3.cnnic.cn/n4/2025/0117/c88-11229.html (accessed on 12 November 2025). (In Chinese).

- Chiu, T.-K., Lin, T.-J., & Lonka, K. (2021). Motivating online learning: The challenges of COVID-19 and beyond. Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 30, 187–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, R. J. C. (2010). How family support and internet self-efficacy influence the effects of e-learning among higher-aged adults: Analyses of gender and age differences. Computers & Education, 55, 255–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Descals-Tomás, A., Rocabert-Beut, E., Abellán-Roselló, L., Gómez-Artiga, A., & Doménech-Betoret, F. (2021). Influence of teacher and family support on university student motivation and engagement. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietrich, J., Greiner, F., Weber-Liel, D., Berweger, B., Kämpfe, N., & Kracke, B. (2021). Does an individualized learning design improve university student online learning? A randomized field experiment. Computers in Human Behavior, 122, 106819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, Y., & Baissberg, S. (2025). Redefining boundaries: Unveiling the schism in teacher–parent perceptions of educational engagement. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1539049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, H., Ou, Y., Zhang, Z., Ni, M., Zhou, X., & Liao, L. (2021). The relationship between family support and e-learning engagement in university students: The mediating role of e-learning normative consciousness and behaviors and self-efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 573779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Growth Insights. (2025). E-Learning services market size, share & growth report, 2032. Available online: https://www.globalgrowthinsights.com/zh/market-reports/e-learning-services-market-100948 (accessed on 12 November 2025). (In Chinese).

- Gogol, K., Brunner, M., Goetz, T., Martin, R., Ugen, S., Keller, U., Fischbach, A., & Preckel, F. (2014). “My questionnaire is too long!” The assessments of motivational-affective constructs with three-item and single-item measures. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 39(3), 188–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhow, C., Graham, C. R., & Koehler, M. J. (2022). Foundations of online learning: Challenges and opportunities. Educational Psychologist, 57(3), 131–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helbling, L. A., Tomasik, M. J., & Moser, U. (2019). Long-term trajectories of academic performance in the context of social disparities: Longitudinal findings from Switzerland. Journal of Educational Psychology, 111(7), 1284–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, H. C., Poon, K. T., Chan, K. K. S., Cheung, S. K., Datu, J. A. D., & Tse, C. Y. A. (2023). Promoting preservice teachers’ psychological and pedagogical competencies for online learning and teaching: The TEACH program. Computers & Education, 195, 104725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- iResearch Consulting Group. (2017). 2017 white paper on online learning among Chinese university students. Available online: https://www.idigital.com.cn/report/detail?id=3093 (accessed on 12 November 2025). (In Chinese).

- Keser Aschenberger, F., Radinger, G., Brachtl, S., Ipser, C., & Oppl, S. (2023). Physical home learning environments for digitally-supported learning in academic continuing education during the COVID-19 pandemic. Learning Environments Research, 26(1), 97–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legge, J. (2004). The religions of China: Confucianism and Taoism described and compared with Christianity 1880. Kessinger Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, X., & Kantor, J. (2022). Social support and family quality of life in Chinese families of children with autism spectrum disorder: The mediating role of family cohesion and adaptability. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 68(4), 454–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H., Liu, Q., Du, X., Liu, J., Hoi, C. K. W., & Schumacker, R. E. (2023). Teacher–student relationship as a protective factor for socioeconomic status, students’ self-efficacy and achievement: A multilevel moderated mediation analysis. Current Psychology, 42(4), 3268–3283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R., & Chiang, Y. L. (2019). Who is more motivated to learn? The roles of family background and teacher–student interaction in motivating student learning. The Journal of Chinese Sociology, 6(1), 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y., Zhao, L., & Su, Y. S. (2022). The impact of teacher competence in online teaching on perceived online learning outcomes during the COVID-19 outbreak: A moderated-mediation model of teacher resilience and age. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(10), 6282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Logan, J., & Spitze, G. (1996). Family ties. Temple University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, X., Jiang, M., & Nong, L. (2023). The effect of teacher support on Chinese university students’ sustainable online learning engagement and online academic persistence in the post-epidemic era. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1076552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, F., & Borup, J. (2022). Online learner engagement: Conceptual definitions, research themes, and supportive practices. Educational Psychologist, 57, 162–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, H., Wang, S., Tao, Y., Tang, Q., Zhang, L., & Liu, X. (2023). The association between online learning, parents’ marital status, and internet addiction among adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic period: A cross-lagged panel network approach. Journal of Affective Disorders, 333, 553–561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, C., Fonseca, G., Sotero, L., Crespo, C., & Relvas, A. P. (2020). Family dynamics during emerging adulthood: Reviewing, integrating, and challenging the field. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 12(3), 350–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, D. H., Portner, J., & Bell, R. (1982). FACES II: Family flexibility and cohesion evaluation scales. University of Minnesota. [Google Scholar]

- Pellas, N. (2014). The influence of computer self-efficacy, metacognitive self-regulation and self-esteem on student engagement in online learning programs: Evidence from the virtual world of Second Life. Computers in Human Behavior, 35, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, M. R., West, C. L., Shen, Q., & Zheng, Y. (2004). Comparison of schizophrenic patients’ families and normal families in China, using Chinese versions of FACES-II and the Family Environment Scales. Family Process, 37(1), 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pozzoli, T., Gini, G., & Scrimin, S. (2022). Distance learning during the COVID-19 lockdown in Italy: The role of family, school, and individual factors. School Psychology, 37(2), 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, G., Li, P., Ju, E., Chen, X., & Luo, Y. (2025). Teachers’ emotional exhaustion relates to students’ well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: The multilevel mediating role of students’ perceived teacher–student intimacy. Social Psychology of Education, 28(1), 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, Z. O. U., Zeb, S., Nisar, F., Yasmin, F., Poulova, P., & Haider, S. A. (2022). The impact of emotional intelligence on career decision-making difficulties and generalized self-efficacy among university students in China. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 15, 865–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinke, W. M., Smith, T. E., & Herman, K. C. (2019). Family–school engagement across child and adolescent development. School Psychology, 34(4), 346–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, M., Abraham, C., & Bond, R. (2012). Psychological correlates of university students’ academic performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 138(2), 353–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryan, J. (2019). Education in China: Philosophy, politics and culture. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Sakız, H., Özdaş, F., Göksu, İ., & Ekinci, A. (2021). A longitudinal analysis of academic achievement and its correlates in higher education. SAGE Open, 11(1), 21582440211003085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, A., Rizzuto, T., Carraher-Wolverton, C., Roldán, J. L., & Barrera-Barrera, R. (2017). Examining the impact and detection of the “urban legend” of common method bias. ACM SIGMIS Database, 48(1), 93–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarzer, R., & Jerusalem, M. (1995). Generalized self-efficacy scale. In J. Weinman, S. Wright, & M. Johnston (Eds.), Measures in health psychology: A user’s portfolio. Causal and control beliefs (pp. 35–37). NFER-Nelson. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T. E., Sheridan, S. M., Kim, E. M., Park, S., & Beretvas, S. N. (2020). The effects of family–school partnership interventions on academic and social-emotional functioning: A meta-analysis exploring what works for whom. Educational Psychology Review, 32(2), 511–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H., Kim, J., & Luo, W. (2016). Teacher–student relationship in online classes: A role of teacher self-disclosure. Computers in Human Behavior, 54, 436–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y. (2024). Sustainable growth of learner engagement and well-being through social (teacher and peer) support: The mediator role of self-efficacy. European Journal of Education, 59(4), e12791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spring, K. J., Graham, C. R., Hanny, C. N., Tuiloma, S., & Badar, K. (2024). Academic communities of engagement: Exploring the impact of online and in-person support communities on the academic engagement of online learners. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 36(3), 702–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephen, J. S., & Rockinson-Szapkiw, A. J. (2021). A high-impact practice for online students: The use of a first-semester seminar course to promote self-regulation, self-direction, online learning self-efficacy. Smart Learning Environments, 8(1), 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C. Y., & Guo, Y. (2021). Factors impacting university students’ online learning experiences during the COVID-19 epidemic. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 37(6), 1578–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tackie, H. N. (2022). (Dis)connected: Establishing social presence and intimacy in teacher–student relationships during emergency remote learning. AERA Open, 8, 23328584211069525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y., Meng, Y., Gao, Z., & Yang, X. (2022). Perceived teacher support, student engagement, and academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology, 42(4), 401–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topali, P., Chounta, I. A., Martínez-Monés, A., & Dimitriadis, Y. (2023). Delving into instructor-led feedback interventions informed by learning analytics in massive open online courses. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 39, 1039–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tudge, J. R., Payir, A., Merçon-Vargas, E., Cao, H., Liang, Y., Li, J., & O’Brien, L. (2016). Still misused after all these years? A reevaluation of the uses of Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological theory of human development. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 8(4), 427–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umberson, D., & Thomeer, M. B. (2020). Family matters: Research on family ties and health, 2010 to 2020. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(1), 404–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vachkova, S. N., Vachkov, I. V., Klimov, I. A., Petryaeva, E. Y., & Salakhova, V. B. (2022). Lessons of the pandemic for family and school—The challenges and prospects of network education. Sustainability, 14(4), 2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Dorresteijn, C., Fajardo-Tovar, D., Pareja Roblin, N., Cornelissen, F., Meij, M., Voogt, J., & Volman, M. (2025). What factors contribute to effective online higher education? A meta-review. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 30, 171–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasquez, A. C., Patall, E. A., Fong, C. J., Corrigan, A. S., & Pine, L. (2016). Parent autonomy support, academic achievement, and psychosocial functioning: A meta-analysis of research. Educational Psychology Review, 28, 605–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vayre, E., & Vonthron, A. M. (2017). Psychological engagement of students in distance and online learning: Effects of self-efficacy and psychosocial processes. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 55(2), 197–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C. K., Hu, Z. F., & Liu, Y. (2001). Reliability and validity of the General Self-Efficacy Scale. Chinese Journal of Applied Psychology, 7(1), 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y. S. (2018). Research on teacher–Student relationships in Chinese universities [Doctoral dissertation, Xiamen University]. Available online: https://kns-cnki-net.ezproxy.lib.szu.edu.cn/kcms2/article/abstract?v=0iq8nzQYh5Sd2yKn5flSK3MifO7vzbkw_NWJ4G_YfLbM7GjKeBGAXV4IBo39DWZP5uKhjcXWVIRRhP2pRKkoYGG_jORgxlk19t6yRfebmthGCDIS1xvZIaW1EZEmuSDH_Fg4U2Il0zF_WMynPnnkEB2bnjPQfxyYU05v9_33kabiF0g-wFEr2rn7yskv6X7jywbeAXCo5EI=&uniplatform=NZKPT&language=CHS (accessed on 12 November 2025). (In Chinese).

- Weidlich, J., Yau, J., & Kreijns, K. (2024). Social presence and psychological distance: A construal level account for online distance learning. Education and Information Technologies, 29(1), 401–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, B., & Song, G. (2022). Association between self-efficacy and learning conformity among Chinese university students: Differences by gender. Sustainability, 14(14), 8725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., Liu, K., Li, M., & Li, S. (2022). Students’ affective engagement, parental involvement, and teacher support in emergency remote teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from a cross-sectional survey in China. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, 54, S148–S164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z. (2022a). A meta-analysis and bibliographic review of the effect of nine factors on online learning outcomes across the world. Education and Information Technologies, 27, 2457–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z. (2022b). Sustaining student roles, digital literacy, learning achievements, and motivation in online learning environments during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability, 14, 4388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y., Wang, W., Song, T., & Li, Y. (2022). The mechanisms of parental burnout affecting adolescents’ problem behavior. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(22), 15139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X., Chu, C. K., & Lam, Y. C. (2022). The predictive effects of family and individual wellbeing on university students’ online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 898171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zou, W., Ding, X., Xie, L., & Wang, H. (2021). Relationship between higher education teachers’ affect and their psychological adjustment to online teaching during the COVID-19 pandemic: An application of latent profile analysis. PeerJ, 9, e12432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | M (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Online learning outcomes | — | 2.88 (0.82) | |||

| 2. Family relationship | 0.308 ** | — | 3.25 (0.85) | ||

| 3. Teacher–student relationship | 0.344 *** | 0.474 *** | — | 3.34 (0.76) | |

| 4. Self-efficacy | 0.283 ** | 0.306 ** | 0.425 *** | — | 3.26 (0.73) |

| 5. Household registration category | 0.062 | 0.109 | 0.190 | 0.059 | |

| 6. Student’s average monthly living expenses | 0.168 | 0.223 * | 0.153 | 0.134 | |

| 7. Father’s education level | 0.098 | −0.021 | −0.067 | −0.031 | |

| 8. Mother’s education level | 0.059 | −0.003 | 0.042 | 0.028 | |

| 9. Cumulative online course duration | 0.144 | −0.126 | 0.001 | −0.069 | |

| 10. Age | −0.002 | −0.023 | 0.007 | 0.000 | |

| 11. Gender | −0.040 | 0.003 | 0.005 | 0.010 |

| Path | β | 95%CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | ||

| |||

| Family relationship → online learning outcomes | 0.180 | 0.118 | 0.244 |

| Teacher–student relationship → online learning outcomes | 0.269 | 0.187 | 0.354 |

| |||

| Direct effects | |||

| Family relationship → online learning outcomes | 0.120 | 0.053 | 0.187 |

| Teacher–student relationship → online learning outcomes | 0.132 | 0.064 | 0.199 |

| Family relationship → self-efficacy | 0.263 | 0.197 | 0.338 |

| Teacher–student relationship → self-efficacy | 0.331 | 0.261 | 0.397 |

| Self-efficacy → online learning outcomes | 0.269 | 0.196 | 0.346 |

| Indirect effects | |||

| Family relationship → self-efficacy → online learning outcomes | 0.071 | 0.046 | 0.104 |

| Teacher–student relationship → self-efficacy → online learning outcomes | 0.089 | 0.060 | 0.125 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Deng, Z.; Jiang, C.; Chi, S. Family vs. Teacher–Student Relationships and Online Learning Outcomes Among Chinese University Students: Evidence from the Pandemic Period. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1682. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121682

Deng Z, Jiang C, Chi S. Family vs. Teacher–Student Relationships and Online Learning Outcomes Among Chinese University Students: Evidence from the Pandemic Period. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1682. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121682

Chicago/Turabian StyleDeng, Zhiqi, Changcheng Jiang, and Shangxin Chi. 2025. "Family vs. Teacher–Student Relationships and Online Learning Outcomes Among Chinese University Students: Evidence from the Pandemic Period" Education Sciences 15, no. 12: 1682. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121682

APA StyleDeng, Z., Jiang, C., & Chi, S. (2025). Family vs. Teacher–Student Relationships and Online Learning Outcomes Among Chinese University Students: Evidence from the Pandemic Period. Education Sciences, 15(12), 1682. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121682