1. Introduction

In today’s digitally saturated world, higher education students’ natural use of digital tools shapes the way they learn (

Muscanell & Gay, 2025). Incorporating technology into learning is mostly impacted by students’ beliefs about improved performance and benefits, such as increased productivity or better task accomplishment (

Xue et al., 2024). Notably, as the value of technology lies in the way it is used, students have found many ways to use technological tools for accomplishing academic tasks. For example, students have used social networking sites—which were originally designed for pure social interactions—in the context of many learning-related tasks, such as facilitating discussions with peers, obtaining and providing logistical information and knowledge, seeking for moral support, or promoting themselves academically (

Lampe et al., 2011;

Prestridge, 2014;

Selwyn, 2009). That is, through digital technologies they use in everyday life, students develop inventive practices that also support and extend their learning (

Sharpe & Beetham, 2010;

Yot-Domínguez & Marcelo, 2017).

This is also true regarding the rise of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) systems, which are based on large language models (LLM) to communicate with users in natural language. This new technology has rapidly become a daily companion in students’ personal and academic lives; it offers new forms of assistance in various learning-related tasks, such as reading and learning, writing and presenting, and managing study processes. Alongside clear opportunities, this diffusion surfaces pressing questions for higher education about assessment practices, institutional strategy, and academic integrity (

Ahmed et al., 2024;

Batista et al., 2024;

Limna et al., 2023;

Mittal et al., 2024). Understanding how students actually use GenAI is not merely a matter of curiosity; it is essential for informed policy and pedagogy. Given the wide range of possible uses, analyses should be conducted at the task level.

Indeed, students’ engagement with GenAI is a complex landscape. Among the numerous applications of GenAI in higher education are such that promote collaboration, personalization, writing, problem-solving, interactive learning, project-based learning, written communication, coding skills, professional competencies, creativity, and critical thinking (

Belkina et al., 2025;

Perifanou & Economides, 2025). Notably, such uses may differ by discipline, which is evident, for example, by comparing reviews of GenAI implementations in health education, engineering education, and language teaching. While in health education, using GenAI is mostly for practice, inquiry, production, and acquisition, and much less for discussion and collaboration—in language learning it is more oriented towards personalization and writing, and in engineering education it tends to focus on implementing projects effectively and creatively (

Belkina et al., 2024;

Law, 2024;

Pham et al., 2025). Hence, looked at in a higher resolution, the implementation of GenAI in academic studies is dependent not only on the subject matter, but rather on the task involved (

Hershkovitz et al., 2025).

Incorporating GenAI into the very core of students’ academic pursuits is valuable from a cognitive perspective. GenAI tools do not merely replace learning-related tasks, but rather reshape the very processes of learning by functioning as partners in cognition (

Salomon et al., 1991). Indeed, GenAI-based tools serve as collaborators in various tasks, e.g., writing, art creation, coding, or knowledge sharing (

Fahad et al., 2024;

Luther et al., 2024;

Safari et al., 2024;

Zhu et al., 2024) in ways that may empower students (

Huang & Wang, 2025;

D. Zhang et al., 2024). Therefore, understanding this partnership requires attention to the task-specific contexts in which students implement these tools.

Documenting students’ authentic practices of using GenAI is crucial not only for academic theory but also for guiding institutional policy. Without such knowledge, universities risk implementing strategies that either underutilize or overregulate technologies that are already shaping students’ academic lives. In practice, and contrary to the cognitive partnership scheme, many higher education institutions’ policies refer to GenAI as an external assistance separate from students’ independent efforts and intellectual contribution; as a result, many policies emphasize issues of misconduct in GenAI use and focus on its threat to academic integrity, instead of referring to how it can help in promoting learning and teaching (

Arista et al., 2024;

Jiahui, 2024).

Taken together, understanding in which tasks students use GenAI-based tools is of great importance. Previous studies indicated the impact of these tools to specific learning-related tasks such as writing, researching, or information retrieval (

Karunaratne & Adesina, 2023;

Levine et al., 2025;

Sysoyev & Filatov, 2023). These studies and others emphasize how GenAI supports learning thanks to its immediacy and multiple capabilities—hence, helping students in completing tasks more effectively and efficiently than before—while keeping their own voice. Recently, an exploration of students’ uses of GenAI was published (

Havelka et al., 2025), however it was limited in two ways: First, it was conducted in a top-down manner, that is, while surveying students about a given set of tasks; second, the population included only Social Sciences students. Hence, a comprehensive understanding of learning-related uses of higher education students is still lacking.

This is indeed the gap we bridge in this study. Therefore, our leading research question is the following: What are the main academic tasks in which higher education students use GenAI-based tools, and how are these uses organized across different channels of learning activity? We answer this question in a bottom-up manner, while including students from all academic disciplines, without limiting ourselves to a specific GenAI-based tool.

3. Findings

Our framework of higher education students’ uses of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) for academic purposes is composed of eight themes: Writing (434 statements of 825, 53%), Learning (330, 40%), Reading (329, 40%), Searching (194, 24%), Meta-learning (116, 14%), Multimedia (38, 5%), Analysis (29, 4%), and Learning Aids (23, 3%). We will now elaborate on each of these themes, some of which include sub-themes. See

Table 1 for a summary of this framework.

3.1. Theme 1: Writing—Using GenAI for Planning, Drafting, and Refining Academic Texts and Computer Code

Over half of the statements referred to using GenAI-based tools for tasks related to writing—e.g., assignments, reports, theses, etc.—whether they involve narrative texts or computer code (i.e., programming). We gathered these two genres, as we found a high level of similarity between the actual uses on which students reported for both of them. However, we will first describe this theme regarding narrative text, and then will demonstrate how it also relates to coding.

As it seems, students use GenAI-based tools on either side of their thought process when engaged in writing. That is, they either use these tools to launch their writing, making this task easier by setting some grounds for it before doing their own writing; or they use it after completing writing, for purposes of polishing the final product in aspects which they consider tedious, like dealing with citations and bibliography, in areas in which they lack competency, like language, or regarding reviewing the final product. These are the two sub-themes.

3.1.1. Pre-Writing

Writing is a challenging task for students, and often beginning it is the hardest part. Using GenAI-based tools ease this process by supplying students with a kick start; mostly, this is done by “Building the structure of academic submissions” (S899) using these tools, or by them suggesting some content, “Starting of writing, one or two paragraphs that I will later edit” (S263). This helps students by giving them something to work with, as is clearly demonstrated in the following statements:

“I ask the system to help me to prepare the submission structure referring to the content, so I do not waste time on thoughts regarding what to write about and in which order”.

(S628)

“When writing an assignment, I use [the tool’s] ideas for a structure, and then write by myself. […] The effect is that I do not deal with a blank page, but [with] something preliminary that enable to start working”.

(S523)

“It is hard for me to write assignments, so I ask AI […] to give me a structure or an opening paragraph, and then I can edit and continue”.

(S289)

Importantly, this kind of assistance is not about the content, but rather about “planning the structure of the answer” (S619) or “building a template” (S1405), in order “to give a general idea about the structure of a response or of a writing assignment” (S422), for getting “help with organizing ideas and thoughts, and how to format them to something I can write about, like an outline” (S227). This makes content-writing more efficient and effective. Even if the GenAI-based tools are used for drafting some preliminary texts, students emphasized that they edit it, e.g.,:

“I mostly use it for open response questions […] for getting kind of a basis to the response, and then I edit it”.

(S1001)

“Structuring assignments (creating headers, general structure, and then going over it and filling up all the relevant missing content)”.

(S1231)

3.1.2. Post-Writing

Writing assignments requires paying attention to three main issues. First, organizing thoughts in a manner that helps the text to convey the desired message, while keeping the text coherent and well-organized logically. Second, the text should be readable, with no grammatical issues or typos. Third, writing also necessitates careful attention to technical issues, like formatting. Students get GenAI-based tools to help them with these three aspects of writing.

At the overall message level, students use these tools “as an ‘assistant’ who will detect errors in logic and explain to me how it reads things I’ve written” (S767), for “checking of texts I wrote, getting ideas for critics” (S1080), and generally to “rephrase what I write in a coherent manner” (S363). That is, students first write by themselves, and only then have the tool review it. This is also evident in the following statements:

“To verify myself—Were there points that I could have addressed but didn’t? Was there information that could be relevant to me and that I could add to the work? Was the connection coherent and clear? (AI as a reviewer)”.

(S1236)

“For help with critics on texts I wrote, in particular on what is the implicit message from them”.

(S556)

“When wanting to ensure that what I have written is being communicated correctly, I will have the system give me the bullet points of what my paragraph/chapter/paper is. If it produces the correct answer, it means that others will likely reach a similar conclusion”.

(S1656)

“Help in fully covering aspects and arguments in the topics I write about”.

(S298)

Regarding formatting, one of the most tedious tasks in writing assignments is inserting citations and bibliography in the correct format, for which students get the assistance of GenAI-based tools, “Technical tasks regarding bibliography” (S843), “Quick and correct writing of references and citations following APA” (S1454), “Organizing the bibliography following the required style” (S1237). Other than that, academic writing tasks are often required to adhere to some guidelines of format, like length; students mentioned using GenAI-based tools for either shorten or expand texts they write to follow the guidelines:

“Rephrasing of too long answers when the assignment has limit on response length”.

(S1000)

“It is hard for me to answer […] if there is a minimum of words to write. Sometimes, I use ChatGPT […] to bulk up texts that I wrote […] to be enough to submit”.

(S784)

As for language, many students mentioned getting help with grammar and style while keeping their own content, e.g., “I give it [the GenAI-based tool] the text [I wrote] and ask it to improve the phrasing or grammar while keeping all details” (S1351), or “rewrite my sentences in a more scientific way” (S1637). This is mostly important when done in English when it is not the writing student’s mother tongue, so they use these tools for “Proofreading and spelling in English” (S1454), “Grammar check and proofreading of texts in English” (S56), and to “Better phrase English texts” (S433). Doing so, students make sure that their own voice—content-wise—is manifested in a clear manner language-wise; sometimes, they “Write in a non-formal way and then referring to an AI engine to improve the text register” (S155), and overall using these tools to “improve the level of the text I submit” (S1281). So, students’ agency is kept while using these tools:

“[I let it] to go over materials I wrote, to see if it is clear and well-written”.

(S174)

“It’s amazing at paraphrasing quotes, something I’ve always had trouble with, and just producing a list of synonyms or providing transitional words or sentences”.

(S1590)

“I give it difficult paragraphs, and it outputs them into simpler sentences”.

(S921)

One participant clearly explained how they are focused on the text itself, and let the GenAI-based tools do the tedious editing work:

“These tools mostly assist me in writing sentences […] in an improved manner, usually it is for texts that repeat themselves that I need to write in a different phrasing each time, and I am not into trying and paraphrasing”.

(S514)

A few students explicitly demonstrated this use when responding to our questionnaire:

“[I use GenAI-based tools for] almost any task […] wording and writing […] to clarifying texts. For example, ChatGPT formulated this sentence at the level of a professor of Mathematics Education”.

(S600)

“I use GPT mainly for writing and editing academic texts. I use it quite a lot, it helps me refine my ideas and formulate things better. (ChatGPT wrote this)”.

(S1155)

3.1.3. Pre- and Post-Writing in the Context of Programming

Notably, these pre- and post-writing uses are also relevant when writing codes. Pre-writing, and more than in the case of narrative texts, students use GenAI-based tools to get involved in content-related issues, that is, in writing some piece of the code, as one of the participants put it, “Coding is exhausting, it takes a lot of time, and I’m bad with it. AI tools can save a lot of time and efforts in writing a simple code” (S778). This is also evident for “auto completion of code” (S103), or to “use the chatbot for syntaxes I do not remember” (S754). This may also help them to focus on higher-level aspects of coding; one of the participants stated that they use GenAI-based tools “mostly for writing code […] so there is no need to invest in syntax. My work speed had doubled, I think” (S219).

Post-writing, students use GenAI-based tools to improve codes. The parallels to the narrative texts’ improvement may be seen mostly in algorithmic and efficiency aspects (compared with style), syntactical errors (compared with grammar), as can be evident in the following statements:

“I write a code that needs perform a task which if I feel is not efficient enough, I use AI to modify it to make it more efficient, as well as sometimes I would ask it if it can suggest me better algorithms for the code I want to write”.

(S1642)

“I mostly use ChatGPT and Claude, and also conduct interactions between them—transfer a code from one to the other for finding errors and asking for improvements. The tools are mostly good for low-medium level codes, for finding errors and documentation”.

(S1252)

Here again, students use these tools to edit, modify, or improve the code they have written by themselves, “to debug code” (S1043), “to check the correctness of a code I wrote” (S635), or “for fixing Python code” (S1421).

3.2. Theme 2: Learning—GenAI as a Tutor for Understanding Material, Navigating Assignments, and Extending Knowledge Beyond the Classroom

About 40% of the responses referred to using GenAI-based tools for learning. These represent three different aspects of learning, which form three sub-themes: understanding the material that was taught in the course, getting help while working on homework, and learning issues beyond what was taught in the classroom.

3.2.1. Understanding Taught Material

Students use GenAI-based tools to have a better understanding of the taught material. While traditionally, students have used office hours or peers, they now have another source of consultation, which is accessible and immediate, “better than waiting a week for a lecturer hour of free time” (S1650), “quicker than to search all the materials I have” (S973), “more convenient […] than to search for it in the book” (S771), and more effective when “I need to understand something quickly, and it does not come up immediately on a Google search” (S1395).

Sometimes, as many had mentioned, they use these tools for writing general summaries for them about the taught material—i.e., with the tools relying solely on LLM-generated text—often students communicate about the specific topics taught and regarding the specific materials used in the course:

“ChatGPT sometimes gets from me my course resources, and I directly ask it questions about the material”.

(S587)

“I copy into Gemini texts that I read, and I discuss them with it, and I ask for explanations to points that are not clear to me”.

(S1189)

Moreover, just like with the instructor or with peers—and unlike looking for the answer yourself within the course materials or online—it is more than just looking for an answer, but rather a conversation:

“Asking specific questions about the whole [course] material […]—I’m creating a dialogue with the software”.

(S1015)

“If a certain topic is difficult for me, I explain it [to ChatGPT] and asks for an explanation”.

(S358)

“You can have a conversation with it, and to extend on all these topics [that I do not understand]”.

(S1505)

This type of use mostly includes these tools as mediators between the students and the taught material, for them to “understand something I did not understand” (S422), “explain texts or unclear concepts” (S692), “breaking down difficult concepts” (S1590), or for “getting help with understanding complex materials” (S974). This supports students in engaging more effectively with the course materials, as it “deepen or simplify what the instructor talks about” (S1412), and it helps them “to answer learning-related questions that I did not understand or did not find the answers to them in the course materials” (S76).

A few participants mentioned issues of correctness when asking about topics they learned, for example, “they know to refer particularly to my request, but unfortunately, they always have mistakes in Linear Algebra and in Physics” (S68). One of the participants referred to AI as “a private tutor who speaks confidently but is sometimes wrong”, and emphasized that “of course they are wrong and misleading sometimes, but using them does make it easier […] or at least helps me understand which questions I have to ask and what actually I do not understand” (S735). Because of this, they sometimes “compare ChatGPT’s answers to other sources on the Internet” (S1528), and state that “this is not the main tool I use [for understanding unclear material], but rather an aid I sometimes use” (S1472).

3.2.2. Help with Assignments

Students often use GenAI-based tools while working on their assignments, but only few mentioned that they use these tools instead of working on the problems by themselves, e.g., “I use ChatGPT in Pass/Fail assignments that I want to complete quickly” (S874). Where participants detailed their way of navigating homework with the use of GenAI-based tools, it was mostly after they had dedicated some meaningful time for trying and solving it:

“When I am stuck, or when I am not sure about the answer I got or about the method I used”.

(S907)

“I use the AI tools mostly to understand problems that I could not solve even after a long thought”.

(S1514)

“I frequently use AI tools if I feel completely overwhelmed by a question […] that can give me leads for Google searches, or a direction for an answer, or inspiration”.

(S1612)

Even then, it is not the mere solution they are asking for, but rather directions for solving it, asking “for a hint, or the formulas or connections relevant to the topic of the question” (S1147), or consulting “about how to answer and how to approach the problem” (S1498). So, they are looking for “guidance as for how to start [the solution]” (S566), or “consult about the structure of the answer” (S1322).

After completing their own solution, students use GenAI-based tools for “comparing solutions” (S56), “making sure of my answers” (S714), or “checking for correctness of part of my solutions” (S922). This may help them to “have a deep understanding of the suggested solution and to try and think of other possible solution paths” (S818).

Whie using such a tool, they do it cautiously, as “it has many computational errors” (S1360), but still then they find it useful:

“In homework assignments I was unable to solve myself, mainly in Mathematics, its help is very limited, often times its answer is wrong, and yet, even in these extreme cases, it is nice for me to consult it”.

(S1424)

“When helping with problem solving, the AI tool gives me the method, and I use it to solve, knowing that the tool’s answer is probably wrong”.

(S717)

“[When I use it to solve a problem] it generates a precise method, which is around 70% of the time accurate. I can nudge it to correct itself within 2 or 3 more correctly worded questions until it’s exactly what I need”.

(S1616)

“When I face a problem I do not understand, after a few solution attempts […] I can use the help of the AI, although it does not always give a correct answer. Still, it gives tools for the solution”.

(S1448)

This use makes working on homework and assignments more efficient on a few levels. First, it may give them a kick start, in getting “kind of a base to my answer, and then I edit it” (S1001), or in writing “general template […] and then to edit it (it is just a Sisyphean work to write code from 0)” (S186).

Second, it enables them to focus on the most important stuff, as they perceive it. That is, they identify what is primary and most important and what is less significant and subordinate, and use the GenAI-based tools in the latter:

“I use [the GenAI-based too] to check the text […] for example, in a Statistics project where it is mostly important to demonstrate knowledge of the material and less important to how nicely the project is written”.

(S797)

Third, it allows them to concentrate on the sheer problems to be solved—which is perceived as an advantage by students—as the GenAI-based tools help them to “quickly get to the solution instead of wasting time on some insight that I might have” (S238), and let them “to create a more focused solution for myself and not look for the solution throughout presentations that are sometimes no longer relevant” (S743).

In addition to these advantages, using GenAI-based tools for working on homework makes students learn from the tools’ solutions. For example, one students mentioned that their “homework often includes high difficulty exercises, so I ask the AI to give me simple examples of how to use the taught material, and from there I understand how to solve more complex problems” (S1250); another stated that they “really love the AI tool because it explains and details the solution stages, and I learn a lot from it” (S195), and yet another student explicitly mentioned that this kind of use, in the context of programming assignments, is done “for improving my knowledge and for being able to use in the future lines [of code] I wasn’t familiar with or I didn’t know how to use [that were found using a GenAI-based tool]” (S1143). This stems from the fact that the AI tools not only give answers but also detail about how to solve the problems. Therefore, students use them to solve homework assignments “in a way from which I learn, as it explains me what I do not understand” (S1241), hence they benefit from the tools “explaining where I was wrong and how to get to the solution” (S448), and from the tools helping in how to approach the problem, as “it gives a perspective to the solutions, and knows to exactly explain the steps of operation” (S897). Student detailed about how they carry out such a use, e.g.,:

“Surely, I do not copy [from the GenAI-based tool], I get a detailed, explained, and in-depth information, I examine it, learn it, rewrite it, and choose what is relevant to the problem I’m struggling”.

(S639)

“I mostly use ChatGPT while solving homework assignments to explain a thought process, different ways of solving the problems, an explanation of why you solve it the way you solve it, and how to approach it”.

(S828)

3.2.3. Learning Beyond the Classroom

The two previous uses under the current theme reflect students’ communication with GenAI-based tools for learning about content that is directly and specifically associated with their classroom learning—either the very taught material or homework tasks. However, often times they use these tools to extend their knowledge beyond this narrow point of view. At the simplest manner, they wish to extend their knowledge within a small radius around the taught materials, e.g., “what stands behind the code I learn (usually, statistical models)” (S1143), “more details about what was taught for which I want to get more examples and further information” (S978), or “an understanding in a broader context of specific topics” (S661). So, when they learn new material in class, these tools help students to better engage with it, to “extend my intuition” about it, or as a springboard “to get an overview of it, and to keep researching and understanding by myself from there” (S1325).

Going a bit further in their study-related needs, students use GenAI-based tools when they need help in carrying tasks which are part of their academic endeavor. For example, they use these tools for “obtaining resources for data or for data analysis, and also to operate the computer, like taking a screenshot” (S185), for “generating scripts for analyses I would run on R” (S880), or “to understand research methods” (S482).

3.3. Theme 3: Reading—GenAI Support for Summarizing, Translating, and Querying Texts and Other Learning Resources

About 40% of the responses referred to using GenAI-based tools as an aid for reading academic materials. A vast majority of the statements referred to narrative texts, for which students mentioned different usage scenarios, specifically, summarizing, querying, translating, and transcribing. Here too—like in the Writing theme—we include computer programs for which some of these uses are relevant. Also, some students mentioned using GenAI-based tools to “read” video sources by implementing text-related practices.

Summarizing and querying helps students to engage with written materials more efficiently. Often, they use such practices in cases where they are required to read a lot of materials or merely difficult materials (with “a lot” and “difficult” being purely subjective, based on their own judgement, of course). The tools they use help them to “get the article’s overall idea, where to find in it specific points that are relevant to me” (S1191), to quickly “extract arguments [from a paper]” (S28), or “to find exact quotes from the paper” (S350). Overall, summarizing and querying text materials serve as a means for filtering for relevance or for finding information. Some statements that represent many others are the following:

“Summarizing articles is a way to know whether there is a point in deepening in it, because deepening is still difficult”.

(S1471)

“When I was asked to write an assignment based on paper—instead of reading 100 pages and more, I used the AI to summarize the important stuff, and it helped me answer the questions”.

(S167)

“I use ChatGPT for […] summarizing papers if I don’t have time to read them thoroughly”.

(S1651)

“I manage to get a lot more information in a lot less time. I build my work not on the basis of 5–6 articles I found that took me hours to read and the claims in them are the only ones I can base my work on, but I am able to process dozens of articles in different languages, filter the content, and finally conduct very serious research”.

(S628)

For some students, using such practices is a matter of scaffolding due to learning difficulties, as one of them wrote: “due to attention deficit issues, I can’t read the study materials, it simply doesn’t work, so I use Gemini or ChatGPT to understand these materials and to process them” (S1126).

Students also use GenAI-based tools to read computer programs in a similar manner to their uses with text-based academic materials. They use these tools to “understand a Python code” (S195), as “AI like ChatGPT is very good in […] explaining what a concrete piece of code (like a function) does” (S362). As such, students use them to read a program for “making sure a code I wrote is correct” (S62), for “understanding what is the problem in the existing code” (S302), or for “finding bugs in the code” (S132).

Translating and transcribing are means to make reading tasks easier or feasible. Translating is useful when dealing with materials that are written in languages students are not fluent with (English was most often mentioned, however there are many students for whom Hebrew—the official teaching language in the studied university—is not their mother tongue). Transcribing is useful when dealing with hard-to-read handwriting, or with video or audio files, as “If it is required to learn from a YouTube clip and it is difficult to remember all the information from it, ChatGPT can summarize it” (S587), or for “[recording] the instructor in class or they send me the Panopto recording file […] and then summarize it using LLM” (S1479).

3.4. Theme 4: Searching—Use of GenAI to Locate Academic Sources and Information

In about a quarter of the responses, students stated using GenAI-based tools as a searching tool. While a few generally mentioned “looking for information” or “looking for resources”, in most cases, it was explicitly about searching academic publications; this was done either with dedicated tools, like Elicit, Perplexity, or SciSpace, as they are “easy and reliable” (S233), or with general-purpose tools, like ChatGPT, Gemini, Claude, or Copilot. Regarding the general tools, this was done as an alternative or a complementary to using search engines. Some students clearly mentioned critically reviewing answers regarding this particular use, as “Gemini often reports papers that do not exist” (S1610). Being aware of these tools’ limitations, students “review the answer using my knowledge and another source if necessary” (S587), and use it “as an addition [to academic databases], I don’t rely on it” (S669). Some participants clearly stated that while using general-purpose GenAI-based tools for searching academic papers, they triangulate what they get with more credible sources:

“For article searching, I mainly use Gemini because it is the least inventive, and is aligned with real sources. Then, I go to [Google] Scholar and look for the articles that Gemini recommended to me there”.

(S1191)

“I used GenAI for looking for [academic] materials. Then, of course, I triangulated them with the library database”.

(S992)

The use of GenAI-based tools for searching academic papers make this task more effective and more efficient for students, as “[traditional academic] search engines do not necessarily give me the required outcome” (S259), “it is easier […] to give a prompt than to find keywords” (S419), and the AI tools give them relevant papers that “do not come up as a first result in academic search engines” (S377), so they do not “waste time on searching by myself” (S448). Using the advanced tools, they can, for example, “look for articles that address specific questions” (S1513), “look for relevant literature from prestigious journals to a paper that I already found” (S804), “get an idea about names of scholars that published on the topic” (S1072).

3.5. Theme 5: Meta-Learning—Brainstorming and Managing Learning with GenAI

Students also use GenAI-based tools for meta-cognitive purposes, specifically for brainstorming together with them, and to a much lesser extent—to manage their own learning.

3.5.1. Brainstorming

For brainstorming, many participants had mentioned general terms like “brainstorming”, “giving ideas”, “searching for directions”, or “getting inspiration”; one participant put it clearly: “If I feel stuck on something generally it helps to get me to my next idea or at least provides me with tips on getting unstuck” (S1590), and others used these tools “to organize random thoughts [I have] in a neat format” (S791), “to examine my ideas” (S65), or to “deeply understand a flash of an idea that I have, if it is of interest” (S35). One student mentioned that they “often consult with the AI tools like in a human conversation, to get ideas and motivations for thinking” (S1162).

Brainstorming with these tools mostly relates to the initiations of learning processes, e.g., when looking for topics for projects or for assignments, when wishing to nicely structure a response or a submission, or when asked to set-up research questions. However, brainstorming and inspiration-seeking also happen throughout the learning process, for example, for “explaining some results” (S295), “for statistical approaches” (S360), “when I need an example for something” (S1261), or for “getting intuition, motivation, and implications regarding what I learn” (S115).

3.5.2. Learning Management

Regarding learning management, a few students mentioned using GenAI-based tools to “create a schedule for myself” (S1456), to “plan a task” (S212), or to “for [learning about] learning techniques and [how to better] learn for exams” (S742)—that is, as a way to regulate their own learning. Some use it for emotional regulation, e.g., “I usually use it when I am frustrated with some necessary task and need a place to write my emotions, my progress, get some feedback, and then return to work” (S1627).

3.6. Theme 6: Multimedia—Creating Presentations and Visual Materials with the Help of GenAI

Students use GenAI-based tools for making artifacts, specifically presentations and images, through which they communicate their learning to others. These tools help students to design presentations either at the conceptual or the content levels. As such, the tools help them to work on “the presentation’s structure and think of questions to the class [while I’ll present to them]” (S373), to “create a preliminary layout for the presentation, and to shorten what I read to bullet points” (S998), and to “design presentations” (S57). These tools help students organize their ideas and translate them into effective presentations, by “arranging [the presentation] nicely by sections, with a header slide for each” (S587), by writing “short and clear sentences [that] help me with the Power Point presentations I create” (S1606), or by “using Paraphrasing Tool to make the [presentation’s] content more clear” (S1298).

They also create images and short videos to use in presentations, mainly when “there is no real picture available” (S1258) and because “it is really fun” (S714), and often with “no great success doing it” (S36). Some students mentioned producing multimedia using GenAI-based tools as an integral part of their course of study, for example, “making creatives” in the context of studying about advertisement (S1451), “making visualization for scripts I write” while learning playwriting (S1497), or “making sketches, concept art, or memes” as part of studying Arts (S1409).

3.7. Theme 7: Analysis—Using GenAI for Data Processing and Simplifying Calculations

This theme holds a small but not negligible number of statements, referring to the use of GenAI-based tools for data analysis. Most of those who mentioned this use simply wrote “statistical analysis”, “solving equations”, or “mathematical calculations”. However, some were more elaborated. For example, one student mentioned using these tools for “all kinds of complex calculations for labs in which the calculation is not the main issue” (S1528), another mentioned using them for “solving equations […] just to shorten tedious, boring manual procedures” (S778), and yet another one explicitly stated that they were using such tools for “coding and analysis of data in Excel sheets” (S762).

3.8. Theme 8: Learning Aids—Generating Study Aids with GenAI

This theme, too, like the previous one, holds a small but not negligible number of statements. Participants reported on using GenAI-based tools for creating aids for learning. They mentioned materials in various formats, e.g., creating “demonstrating pictures” (S532), “acronyms to memorize the material” (S811), or “asking ChatGPT to take a topic or a set of concepts, either by a prompt or based on files I upload, and to create flashcards” (S587). Some use these tools to summarize a topic that was taught, as they ask the tool “to emphasize the main points” (S1319), and use these summaries. Specifically, this is relevant when learning for exams, when the GenAI-based tools are used to create mock exams:

“Towards memorizing-based exams, I upload [to a GenAI-based tool] material summaries, and get an exam”.

(S532)

“When I ask ChatGPT to give me [multiple choice] questions, I instruct it to build them in the same way they appear in the exam: four responses, only one is correct”.

(S587)

“I upload to ChatGPT all the course materials and a sample exam, and I ask it to […] come up with more exam questions”.

(S1588)

“I upload the list of topics for the exam, and ask the chatbot to write a difficult multiple choice test with explanations after each answer I enter”.

(S628)

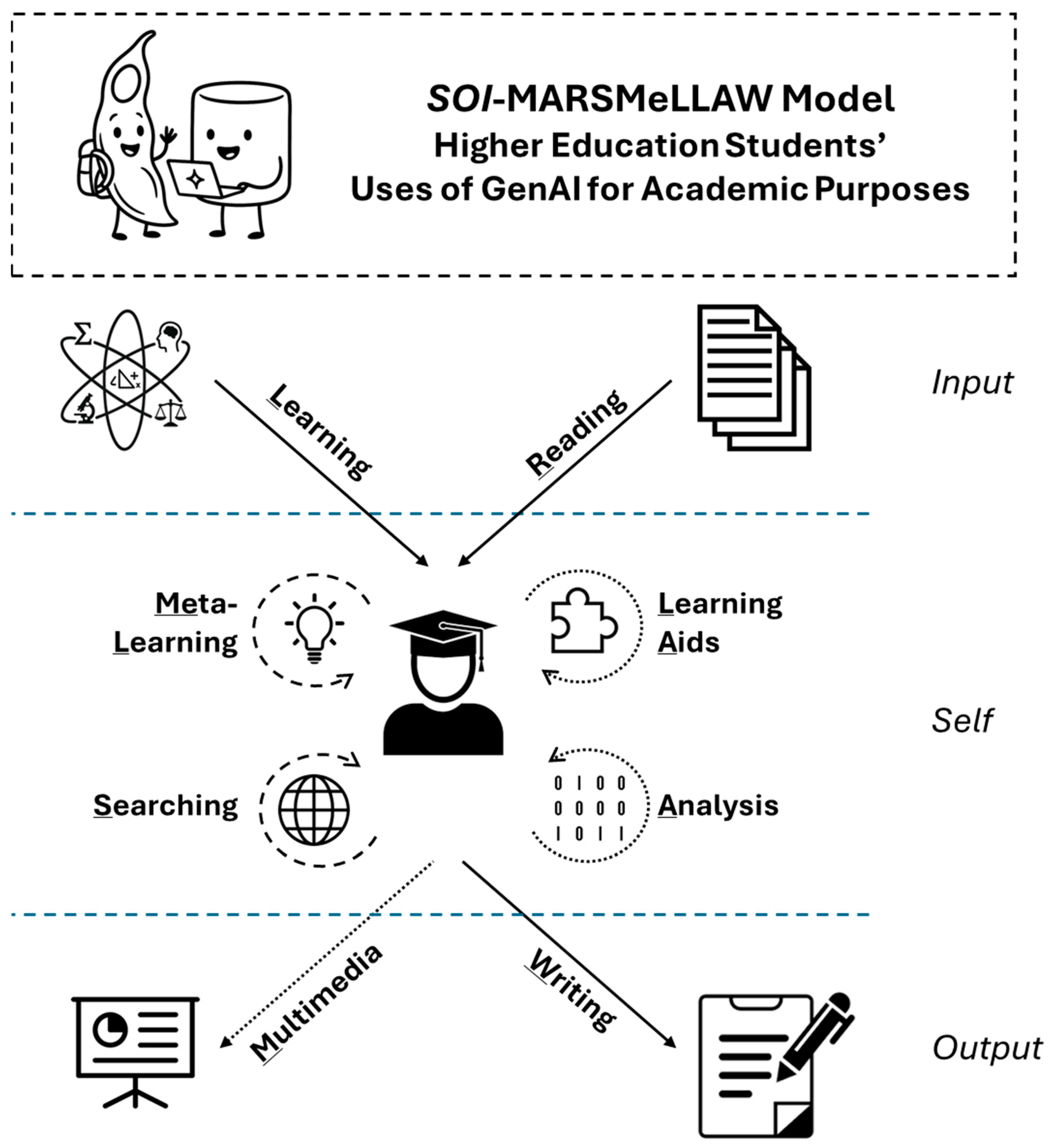

3.9. SOI-MARSMeLLAW Framework

Based on our findings, we define the MARSMeLLAW scheme of students’ use of GenAI for academic purposes: Multimedia, Analysis, Reading, Searching, Meta-learning, Learning, Learning Aids, and Writing (presented here in the order of the acronym, not in order of their frequency).

These themes reflect different technology-mediated relationships between students and various academic resources, and some meaningful technology-mediated relationships between students and themselves. We can divide these relationships into three major channels of information flow: Input, Output, and Self. Input-related themes include Reading, in which students engage with academic materials, and Learning, in which students engage with domain-specific or general knowledge—both refer to situations in which students implement GenAI-based tools in ways that information flow inward, to them. Output-related themes refer to students’ engagement with artifacts they create for communicating knowledge with others: Writing (of assignments) and Multimedia (mostly creating presentations); in these cases, students implement GenAI-based tools in ways that information flow outward, from them. Self-related themes are those in which students communicate with themselves, sometimes related to other academic resources; these include Meta-learning, for brainstorming and learning management; Searching of various information; Learning Aids, mostly for making exam preparation more effective; and Analysis of data. This framework—to which we refer as SOI-MARSMeLLAW (with SOI stands for Self, Output, Input)—is visually presented in

Figure 2, which also uses different line styles to distinguish between themes, based on their frequency.

3.10. Two Comments About Our Framework

Although not set-up a priori as designated research questions, we found ourselves pondering about two issues after concluding our framework. First, are the themes we identified sensitive to domains of study? Second, is GenAI literacy differs by the task in which this technology is being used? We shortly answer these two questions now with the data we have in hand, and this is to be considered as a preliminary examination of these two issues.

3.10.1. Domain-Specificity

As part of the broader study in which the current analyzed data was collected, we also collected data about students’ main course of study. Participants could choose from 10 values, based on the faculties that exist in the studied university. Later, we coded these into two broad categories: (1) STEM, including faculties of Engineering, Medical & Health Sciences, Exact Sciences, Life Sciences, and Neurosciences; (2) Humanities and Social Sciences, including—besides these two—also faculties of Arts, Law, and Management. Now, this data can help us explore differences in themes based on course of study.

Of the 825 eligible responses, we have 50% participants from each faculty category, with 413 students from the STEM disciplines, and 412 from the Humanities and Social Sciences. Using t-test analysis to compare frequency of each of the themes between these two independent groups, we found that four themes are manifested differently. Learning-related uses are more prominent in the STEM fields, with a medium-high effect size; uses for Reading, Meta-learning, and Searching are more prominent in the Humanities and Social Sciences, with medium-high, low-medium, and low effect sizes, respectively. The other themes did not demonstrate significant differences based on course of study. See a summary of these findings in

Table 2 summary.

3.10.2. Task-Centered GenAI Literacy

In a previous work, we developed a framework for GenAI literacy, defined as the ability to effectively and efficiently use GenAI-based tools to simplify, enrich, or better learning-related tasks (

Hershkovitz et al., 2025). We did so in the context of higher education, and formulated it in a way that it is centered on a task. That is, the skills that we defined as part of this literacy all revolved around a specific task, highlighting that different tasks may require different skills.

As we mentioned in the

Section 2, the data that was analyzed here—students’ answers to a single open-response item—was part of a larger questionnaire. That questionnaire also measured our task-centered GenAI literacy, and participants were asked to choose a task to which they would refer while answering the literacy-related items. This allowed us to partially explore how different tasks correspond to the literacy students need when completing them with GenAI-based tools.

In the original item, we presented students with seven tasks to choose from: Studying New Material; Working on Home Assignments; Searching, Reading, or Summarizing Articles; Writing or Editing Texts; Summarizing Lectures; Studying Towards an Exam; Time Management; we also allowed them to choose their own task, and some indeed did. As a preliminary examination of how task-centered GenAI literacy may differ along our SOI-MARSMeLLAW framework, we turned to that data, and wished to code those tasks to the themes we developed here.

Of the given tasks, four were mapped to Learning (Studying New Material, Working on Home Assignments, Summarizing Lectures, Studying Towards an Exam), one was mapped to Writing (Writing or Editing Texts), and one to Meta-learning (Time Management). The pre-defined option of Searching, Reading, or Summarizing Articles could not be mapped to a single theme of our framework. Some free form responses were also mapped to our framework (e.g., “Searching bibliography”→Searching, “Translating articles”→Reading, “Creating images for visual inspiration”→Multimedia). Of the 1667 responses, 772 (46%) were mapped to Learning, and 348 (21%) to Writing; the other themes were much less prominent, with only a few responses mapped to each; also, there were 515 (31%) responses that were not mapped, mainly due to the choice of ambiguous Searching, Reading, or Summarizing Articles, or due to ambiguous, multi-theme-related choices (e.g., “Researching articles and writing papers”, “Everything”).

So, we are left with the ability to compare between Learning- and Writing-related tasks. Also, we know from our previous analysis (

Hershkovitz et al., 2025) that task-centered GenAI literacy is impacted by gender, age, and discipline of study, with men score higher than women, older students score lower than younger, and STEM students score higher than students in the Humanities and Social Sciences. For controlling these variables, we ran a linear regression model, predicting Task-Centered GenAI Literacy based on Gender, Age, Discipline, and Theme (using JASP Version 0.95.2).

Overall, the model was significant, with F(df = 4) = 15.6, at

p < 0.001, albeit with a small predictive power, Adjusted R

2 = 0.05. Notably, all of the predictors are significant, including specifically Theme (see

Table 3). Per the resulting model, Task-Centered GenAI Literacy is significantly higher for Writing-related tasks than for Learning-related tasks. This finding cautiously hints towards differences in students’ GenAI literacy when using it for different tasks.

4. Discussion

In this paper, we analyzed higher education students’ actual uses of GenAI-based tools for academic purposes. As a result, we developed the SOI-MARSMeLLAW framework, which identifies eight distinct categories of GenAI use across students’ academic tasks. These uses relate to three main channels of information processing and communication: Input—engagement with academic resources and domain-specific or general knowledge, which include Reading and Learning; Output—engagement with artifacts they create for communicating knowledge with others, including Writing and Multimedia; and Self—communication with themselves, sometimes related to other academic resources, including Meta-learning, Learning Aids, Searching, and Analysis. The SOI-MARSMeLLAW framework was generated inductively through a conventional content analysis, following theme identification and a conceptual grouping of these themes based on their functional roles in students’ learning processes. The resulting structure reflects this analytical synthesis rather than a pre-imposed framework. We also highlight that Input- and Output-related themes, besides Multimedia, are more prevalent than Self-related themes, with Learning Aids, Analysis, and Multimedia being the least frequent.

4.1. The Unique Case of Using GenAI in Education (And a Mirror to Cognition-Technology Relationships)

A recent report by OpenAI, the company behind the highly popular ChatGPT, which inaugurated the LLM era, identifies a few high-level conversation topics with this LLM-based chatbot (

Chatterji et al., 2025). Analyzing a random sample of approximately one million messages of users, between May 2024 and June 2025, this study found six coarsely defined categories: Writing, Practical Guidance, Technical Help, Multimedia, Seeking Information, and Self-Expression (plus an Other/Unknown category). We can identify some overlap between these categories and our themes, specifically Writing, Multimedia, and Searching (=Seeking Information). That our framework holds a different scheme highlights that learning-related uses may differ from the general population’s. Indeed, when discussing the use of such tools in other domains, the resulting scheme may look totally different (e.g.,

Biswas, 2023;

Burger et al., 2023). That is, we emphasize that the use of technology should always be discussed in a specific context, and this is particularly important while discussing strengths and weaknesses and when discussing policy (

Mai et al., 2024;

Tillmanns et al., 2025). Recently, a typology of students’ use of ChatGPT was introduced (

Petrič, 2024), and it echoes our framework, however with some prominent differences. Mostly, it differs in the prominence of some categories (e.g., brainstorming, a use that 93% of the students reported using at least occasionally), and in the inclusion of categories that we did not have at all (e.g., problematic use, and escapism). These differences are probably a result of methodological differences—their approach was top-down, i.e., surveying about specific tasks, and they only surveyed Social Sciences students, asking only about ChatGPT—not to mention that the study was carried out in a different country than ours (Slovenia); in any case, there is a need to continue studying such uses, doing so across educational settings.

Mioduser’s (

2005) seminal framework for reciprocal relations between cognition and technology identified nine such relations, and our wealth of findings about students’ GenAI uses may be examined via this framework. Students use GenAI as a facilitator for acquiring knowledge (acquisition), e.g., by using it to understand taught material quickly and on demand. GenAI augment students’ cognition and amplify higher-order cognitive processes (extension), e.g., when used to carry out the mechanical, tedious tasks that are part of their work. GenAI helps in activating latent skills (consolidation), e.g., by stimulating reasoning-validation and rehearsing for exams in an authentic manner. These tools help students present their organized thoughts (externalization) and assimilate conceptual models (internalization) by, e.g., creating multimedia products or getting summaries, respectively. Students use GenAI-based tools as “object to think with” that turn making into thinking (construction) when they use these tools to review their own knowledge, and they use these tools as social collaborators (collaborative creation) when they read and write. These tools also compensate for essential channels that are impaired (compensation), e.g., when using it to overcome language barriers. Finally, the new technology also co-evolves with cognition (evolution), and the latter is demonstrated, e.g., by the need to master the art or prompting. These represent rich, varied relations between learners and GenAI, which contributes to the long-lasting discussion in this area.

Note that the uses that we identified span across input, output, and self-thinking channels. That is, GenAI is situated amidst various learning-related processes. This echoes the decades-old notion of intelligent technologies as partners to human cognition (

Salomon et al., 1991), now potentially realizable as never before (

Bobba, 2025). Following these increasingly tight relations, evidence is also starting to accumulate about potential threats of excessive use of GenAI-based tools to human cognition (

Bai et al., 2023;

Dergaa et al., 2024;

Kosmyna et al., 2025). These issues should be further studied, and meanwhile institutions should consider the potential risks for learners when over relying on GenAI.

Additionally, our findings about the importance of the task for which GenAI is used are also important for GenAI education and support. This stresses the importance of choosing the right tool for the right task. As students implement GenAI-based tools in the context a wide range of tasks, they do so in different resolutions (e.g., designing a research paper structure vs. rephrasing a sentence) and in different stages of the learning endeavor. Therefore, the ongoing process of students’ engagement with GenAI is not necessarily linear, and may deviate from the traditional shift from passive to active to constructive to interactive (

Chi & Wylie, 2014). This is an important notion that has both theoretical and practical inferences. Previous technologies that have been used in higher education were mostly single purposed on either the technological or the learning side. For the former, think of search engines, presentation-creation tools, or software for making quizzes; for the latter, think of intelligent tutors, or even learning management systems. The technology discussed here is multi purposed on both the technological and the learning sides. It is not surprising then that much attention has been put on the single interface that is common to all such uses, namely, prompting, to the point that prompt literacy or prompt engineering were suggested as key for today’s learners (

Chen et al., 2024;

Federiakin et al., 2024;

Meskó, 2023). Based on our findings, we believe that GenAI education should go beyond prompting towards a re-examination of learners-technology relations and institutional interfaces in their meeting points.

4.2. Students’ Uses of GenAI (And Institutions’ Response)

As our findings suggest, Writing, Learning, and Reading are the most prominent themes of students’ uses, while Multimedia, Analysis, and Learning Aids are the least frequent. It is interesting to compare these findings to other studies of students’ uses of GenAI-based tools. For example, an analysis of US medical students’ use of ChatGPT in medical school activities shows—similarly to our findings—that ChatGPT users are most commonly using it for writing, editing, and grasping new information, which echoes our findings regarding the prominence of the Writing and Learning themes (

J. S. Zhang et al., 2024). The prominence of the Writing- and Learning-related uses were also found in other studies of students’ uses (

Delello et al., 2023;

Golding et al., 2025), and a recent literature review emphasizes these uses (

Albadarin et al., 2024). As our study took a bottom-up approach, did not refer to a specific technological tool, and included students from a truly multidisciplinary research university—it allowed us to identify the full scope of such uses.

Broadly speaking, across the themes, students mostly use GenAI-based tools to support, rather than replace, learning processes, and the extent of use heavily depends on their abilities and on the task characteristics. It seems that efficiency is a major reason for their use, which is evident across the themes, and specifically in the most prominent themes, i.e., Writing, Learning, and Reading. This raised an important issue to which we do not have an answer yet: Whether this efficiency-oriented use of GenAI comes at the expense of meaningful learning experiences? For example, using GenAI to reduce the number of papers they read, by filtering the most relevant ones, may cause students to read less papers overall; using GenAI to rephrase or translate texts they write may lead students to be less actively engaged with styling, grammar, and foreign languages; and using GenAI to summarize what has been taught in the classroom may bring students to be less exposed to the whole of the course resources. Recent meta-analyses found moderate to large positive impact of students’ use of GenAI-based tools on academic achievements, learning perception, and the fostering of higher-order thinking (

Liu et al., 2025;

Wang & Fan, 2025); however, these issues should be further studied in the context of task-completion, for having a better understanding of the involved mechanisms and of their impact on problem-solving.

As our data suggests, students navigate wisely between possible such uses and adapt the role of GenAI in completing the task to their own needs. GenAI can be incorporated into learning in three main configurations: (1) GenAI as auto-pilot, used to complete tedious tasks; (2) GenAI as co-pilot, used in a collaborative manner, with a high degree of suspicion; and (3) Human as pilot-in-command, where GenAI is not used (

Safari et al., 2024). While the two first scenarios are evident in our findings, the third is only hinted, which may be an artificial product of our methodology, as our leading question referred to actual uses of GenAI. Figuring out when students do not use GenAI is a research avenue we are planning to take.

Having this full picture of students’ uses is important from two complementary perspectives. On the one hand, knowing which are the more prominent uses may direct educators, education leaders, policy makers, and developers to direct their efforts to the areas where students are mostly engaged with GenAI; on the other hand, understanding which uses are less prevalent may make us ask why this is the situation. This dual understanding of students’ use of GenAI also helps us refer to the current challenges of using GenAI in higher education, the major of which are assessment practices, institutional strategies, and risks to academic integrity (

Batista et al., 2024). The prominence of the Writing theme is definitely something to consider while thinking about assessment of students’ written products (either narrative texts or computer programs); the broad understanding of students’ uses and of the frequency of these uses may inform institutional or departmental curricular decision-making; and although our findings do not point out to any critical misconduct—to the contrary, as we emphasized in the previous paragraph—it is important for both students and institutions to make sure the use of GenAI is done in an ethical manner (

Albadarin et al., 2024;

Lo, 2023;

Mienye & Swart, 2025;

Sok & Heng, 2024).

Notably, there are some differences between participants when comparing between the two broad categories of STEM vs. non-STEM disciplines. Specifically, Learning-related uses were more prominent in the STEM disciplines, while Reading-, Searching-, and Meta-learning-related uses were more prominent in the non-STEM disciplines. These differences may make sense when thinking about the ways in which different subject matters have been traditionally taught and learned (

Becher, 1994;

Lindblom-Ylänne et al., 2006) and about disciplinary differences in the use of technology (

Lam et al., 2014;

Sundgren et al., 2023). Importantly, these differences are important when thinking about institution-level GenAI policies, which should better be sensitive to academic discipline (

Mercader & Gairín, 2020;

Shelton, 2014). Working together, higher education stakeholders—students, educators, and policymakers—should incorporate GenAI into learning and teaching in ways that support very goals of these institutions, i.e., the acquirement of relevant knowledge, skills and values that will help students thrive.

4.3. Limitations

This research is, of course, not without limitations. First, our study took place in one institution within one country, hence specific educational, technological, and cultural factors may have impacted on the resulting framework and the way it is manifested in our population; even within this local context, our research sample may not be representative of the studied institution, in particular, due to a potential bias in self-selection to respond to the online questionnaire. Second, the higher education system in Israel has some unique characteristics; specifically, a high portion of students begin their academic studies after an army service—sometimes, after another gap year—that is, they are commonly older, more mature than immediate high-school graduates, which may have affected their uses of GenAI-based tools. Additionally, we relied solely on self-report to an online questionnaire, which may have biased students’ responses, specifically preventing them from reporting on all uses or on unethical or problematic uses. Finally, the GenAI field is constantly evolving, with existing tools getting improved and new tools being presented; it is possible that since our data collection, students became more accustomed to using such tools in a host of ways. We recommend replicating this study across diverse educational settings and with varied methodologies to enrich our understanding of how higher education students implement GenAI as part of their academic studies. Still, we believe that our findings have some important implications.

4.4. Conclusions and Implications

Our SOI-MARSMeLLAW framework positions GenAI in the context of learning in higher education across eight themes, which represent input (Learning, Reading), output (Writing, Multimedia), and self-thinking (Meta-learning, Searching, Analysis, Learning Aids) channels. This nuanced portrait has a few implications. At the practical level, we urge higher education institutions to educate towards comprehensive task-centered GenAI literacy and to provide discipline-tuned guidance and toolkits, acknowledging that literacy may differ by task and learner profile; institutions should also redesign assessment to favor process evidence over outcome, and to enact clear policies for ethical use, attribution, and privacy, supported by faculty development. At the theoretical level, our framework situates GenAI as a distributed cognitive technology that operates across learning-related channels and with which students implement multiple relations; as such, it necessitates a fine-tuned, higher-resolution examination of using GenAI-based tools in educational contexts; this also implies that GenAI literacy is a multidimensional construct that may be dependent on various personal and contextual factors. At the methodological level, our study is significant for designing GenAI-related studies in education contexts, as it emphasizes the need to refer to specific tasks; when task is neither a dependent not an independent variable—it is important to sample across tasks. All in all, the education landscape cannot ignore or reject the GenAI era; rather, we believe that this study will open doors to more fruitful, effective and efficient incorporation of this new technology that will help students, educators, and institutions.