Abstract

Twice-exceptional students, those who are both gifted and have an additional educational need, represent a complex and underserved population within education systems. While recognition of twice exceptionality has greatly increased in gifted education literature, little is known about the experiences of students and their families in Ireland, where no national policy or framework currently addresses their dual needs. This exploratory mixed-methods study aimed to examine the perspectives of 232 parents of twice-exceptional children who attended an enrichment summer programme for gifted students. Through an anonymous survey, the researchers investigated the frequency of specialised services provided for both giftedness and disabilities, as well as how satisfied parents were with these services. The findings indicated that, while two-thirds of students did receive special education support, the majority received no services focused on their giftedness. Parents expressed significantly higher dissatisfaction with gifted provisions than with special education, mentioning the lack of differentiation and access to advanced materials in class, as well as an emphasis on their child’s challenges, as opposed to their strengths. The study’s findings highlight substantial policy and practice gaps in Ireland’s current provision for twice-exceptional students and underscore the need for integrated support systems, teacher education, and inclusion of parent perspectives in educational planning.

1. Introduction

Twice-exceptional learners are students with gifts and talents who also have one or more learning disabilities. This can present a unique educational paradox, as students’ cognitive abilities can mask their learning challenges, while learning disabilities may also obscure their giftedness, leaving them often misunderstood and underserved within educational settings. While recognition of twice exceptionality has greatly increased in international gifted education literature, research in Ireland remains limited. There is currently no research on the types of services received by twice-exceptional students at school, or on their experiences in mainstream education generally.

In Ireland, there has generally been sparse attention given to the provision of services for children with exceptional academic ability (T. L. Cross et al., 2018). The Education for Persons with Special Educational Needs (EPSEN) Act (2004) does not include any provisions for children whose educational needs are not met due to their exceptional ability. The National Council for Special Education (NCSE) oversees special education but provides no specific guidance for twice-exceptional students. The Centre for Talented Youth Ireland (CTYI) at Dublin City University remains the only formal organisation for gifted children, operating nationwide.

With a lack of national policy, government funding, dedicated teacher education, or national guidelines for serving twice-exceptional students, parents become a key advocate for their child’s educational needs. Parents often act as central advocates for recognising their child’s exceptionalities (Guilbault et al., 2024), as they can identify early stages of frustration (Dare & Nowicki, 2015) when a child’s education needs are not being adequately met. Parents also play a critical role in the early identification of their child’s abilities (Mollenkopf et al., 2021), even if they are unfamiliar with the label ‘twice exceptional’ (Khan et al., 2025).

1.1. Literature Review

1.1.1. Definitions and Conceptualisation

Ireland does not have any legislation or national policy which defines giftedness. The National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA) published a set of draft guidelines in 2007 for teachers working with gifted students, using the term ‘exceptionally able’, as opposed to gifted. The definition given was as follows: “students who require opportunities for enrichment and extension that go beyond those provided for the general cohort of students” (NCCA, 2007). CTYI, Ireland’s only formal organisation for gifted children, utilises the definition of giftedness provided by the National Association for Gifted Children (NAGC, 2019), which is that students with gifts and talents perform, or have the capability to perform, at higher levels compared to others of the same age, experience, and environment in one or more domains and who require modifications to their educational experience to learn and realise their potential.

The terminology and conceptualisation of twice exceptionality have developed gradually. Early observers such as Hollingworth (1923) and Asperger (1944) described children who combined exceptional cognitive abilities with notable developmental difficulties. The term twice-exceptional was later coined by James J. Gallagher to identify students who are both gifted and disabled (Coleman et al., 2005). Despite decades of research, however, definitional clarity remains unclear (Desvaux et al., 2023; Gelbar et al., 2022). Scholars consistently emphasise that no universally accepted definition exists, resulting in inconsistent identification across educational systems (Abi Villanueva & Huber, 2021). Early work by Brody and Mills (1997) highlighted the paradox of gifted children with learning disabilities, who were often under-identified and underserved. Building on this, Reis et al. (2014) provided the first operational definition of twice-exceptionality in an attempt to guide future research in the field:

students who demonstrate the potential for high achievement or creative productivity in one or more domains such as math, science, technology, the social arts, the visual, spatial, or performing arts or other areas of human productivity AND who manifest one or more disabilities as defined by federal or state eligibility criteria.(pp. 222–223)

1.1.2. Characteristics and Identification Challenges

Although most definitions agree that twice-exceptional learners combine advanced abilities with one or more disabilities, the lack of consensus lies in how these constructs are defined and measured. For instance, cut-offs for giftedness range from the top 1% to 15% of the population, and definitions of disability vary widely across jurisdictions, leading to inconsistent identification in practice (Hamzić & Bećirović, 2021; O’Reilly, 2013; Subotnik et al., 2011). These inconsistencies can contribute to widespread misdiagnosis and misunderstanding of twice exceptionality. Foley-Nicpon et al. (2011) documented a pervasive misconception that “inclusion in gifted programmes and selection for special remedial education services are mutually exclusive,” which is inherently harmful to identification efforts (p. 4). A major challenge in identification is masking, where giftedness and disability can obscure one another or even cancel out, so that the student appears “average” (Abi Villanueva & Huber, 2021; Morrison & Rizza, 2007). To illustrate the complexity of this issue, King (2005) classified twice-exceptional learners into three subgroups: (a) those with subtle disabilities who are easily overlooked or misidentified, (b) those whose gifts and disabilities mask each other and therefore remain unidentified, and (c) those formally recognized as both but who are often defined more by their disability than by their strengths. This framework highlights how masking can take different forms and explains why many twice-exceptional learners fall through the cracks of existing identification systems.

The educational consequences of these dynamics are significant. Many twice-exceptional students report negative school experiences that undermine their well-being and engagement (Ronksley-Pavia et al., 2018). They often exhibit uneven development, for instance, strong academic abilities alongside weaker social or emotional skills, and may struggle with fear of failure, anxiety, perfectionism, and poor self-concept (Hamzić & Bećirović, 2021). Furthermore, delayed or inaccurate diagnosis can have academically devastating and long term consequences for twice-exceptional learners, leaving many without necessary support and at risk (Abi Villanueva & Huber, 2021). In addition to issues with academics, gifted Irish children are more likely to be cyberbullied than the average population; within that cohort, twice-exceptional children reported significantly lower satisfaction with life and significantly higher negative outcomes than other gifted children (Laffan et al., 2024). There is clear evidence that Irish gifted students who attend programs designed to nurture both their academic and affective needs, such as those at CTYI, prefer the educational experiences they receive in these enrichment programmes over their traditional school experiences (McDonnell et al., 2023). Furthermore, a recent study by Dunne et al. (2025) identified factors that contributed to a positive environment for Irish gifted LGBTQ+ students and found that these students also reported more positive experiences in CTYI than in their own schools.

1.1.3. Educational Needs

Research on twice-exceptional students highlights their complex educational needs, requiring both enrichment and acceleration for their gifts and accommodations for their disabilities (Reis et al., 2025). However, service provision models often fail to address this duality, with students receiving either gifted or special education services, but rarely together in a coordinated manner (Foley-Nicpon et al., 2011). One of the most extensively researched interventions for gifted students is acceleration, which involves advancing students through curriculum at a pace commensurate with their abilities (Assouline et al., 2015). Yet, research on acceleration for twice-exceptional students remains limited. While Assouline et al. (2015) documented strong evidence for acceleration’s benefits for gifted students generally, they noted that students with disabilities may face additional barriers to accessing acceleration opportunities. This gap is particularly concerning given that acceleration can provide the intellectual challenge and engagement that twice-exceptional students need, while accommodations address their areas of difficulty.

Recent research by LeBeau et al. (2025) found that twice-exceptional students face significant barriers to academic acceleration, with students diagnosed with specific learning disabilities (SLD), autism spectrum disorder (ASD), or ADHD being 50–70% less likely to receive whole-grade acceleration compared to their non-disabled gifted peers. Despite high cognitive ability (mean IQ ≈ 117), only 8% of twice-exceptional students in their clinical sample experienced whole-grade acceleration, and students with SLD were approximately 50% less likely to be subject-accelerated, suggesting that disability diagnoses may overshadow recognition of giftedness in educational planning.

The concept of ‘dosage effect’—the relationship between the frequency, duration, and intensity of interventions and student outcomes—is well-established in the special education literature (Vaughn et al., 2003; Warren et al., 2007) yet remains underexplored for twice-exceptional learners. Critically, research suggests that the quality of services matters as much as quantity, and that parent knowledge and involvement in service planning significantly impacts outcomes (Epstein, 2001). Despite this, parents often report a limited understanding of what services their children receive, how frequently, and with what quality—a gap that undermines effective support and advocacy (Blue-Banning et al., 2004).

García-Martínez et al.’s (2021) systematic review highlighted that, even for gifted students without disabilities, evidence-based interventions remain limited. Combined with Foley-Nicpon et al. (2011) observation that “less is known about empirically validated treatments and interventions” (p. 4) for twice-exceptional students specifically, this underscores the urgent need for research on effective practices for this population.

1.1.4. Irish Context: Policy and Provision

In Ireland, the Education for Persons with Special Educational Needs (EPSEN) Act categorises special education needs as a restriction in capacity to participate in education, due to a “physical, sensory, mental health, or learning disability, or any other condition causing different learning” (DES, 2004, p. 6). Ireland is considered to have a ‘multi-track’ approach to the provision for students with special educational needs, with students in mainstream schools placed in either a special class designated for a particular disability (or range of disabilities) or receiving supplementary teaching (McCoy et al., 2014). The number of children and young people identified as having special educational needs has increased in Ireland over the past twenty years, making up over a quarter of the school population today (McCoy et al., 2019).

Although ‘exceptional ability’ was included within the 1998 Education Act, it was removed in the subsequent iteration. Identification challenges are expected to be especially pronounced in places where national policy provides no framework for recognising or supporting twice-exceptional learners. In the Irish context, there has been no systematic research on the experiences of twice-exceptional children, despite growing evidence that both gifted and twice-exceptional learners remain underserved (J. R. Cross et al., 2022; Laffan et al., 2024).

The National Council for Special Education (NCSE) is the main body responsible for coordinating and improving special education provision, yet it does not provide guidance on the topic of twice-exceptional learners. While the NCCA did publish a set of draft guidelines in 2007 for teachers working with gifted students, a subsequent review of the effectiveness of these guidelines (NCCA, 2008) showed that, while the guidelines succeeded in supporting school management and teachers regarding school policy for gifted children, they did not give enough support on classroom practice (O’Reilly, 2018).

Within the Irish educational system, socioeconomic factors play a significant role in access to educational resources and support. The Delivering Equality of Opportunity in Schools (DEIS) programme, established in 2005, provides additional resources to schools serving disadvantaged communities, including lower pupil–teacher ratios, additional funding, and support services (Fleming & Harford, 2023). Schools classified as DEIS serve students from areas with higher levels of unemployment, lower educational attainment, and greater social challenges. While DEIS designation aims to promote educational equity, research suggests that gifted education provision may be particularly limited in these settings, where resources are often directed toward meeting basic educational needs rather than advanced programming (Maunsell et al., 2007).

The intersection of twice exceptionality and socioeconomic disadvantage presents particular challenges. Students from lower-income families may face additional barriers to identification, as giftedness is often associated with privilege and access to enrichment opportunities (Borland, 2004). For twice-exceptional students in schools engaged with DEIS, the combination of disability, giftedness, and socioeconomic disadvantage may create compounded barriers to receiving appropriate educational services. Research in other contexts suggests that gifted students from disadvantaged backgrounds are significantly underrepresented in gifted programmes and are less likely to receive advanced educational opportunities (Plucker & Peters, 2016).

There are currently no studies specifically examining policy or services for twice-exceptional children in Ireland. In recent years, we have seen a growing body of research in the field of gifted Irish learners, which can provide us with a sense of the current experience of these students. From studies with gifted Irish children, a subset has been identified who need extra support from the adults in their lives who care about their wellbeing (J. R. Cross et al., 2015). Like those in many other contexts, gifted Irish children need people around them who will understand them and work to establish environments that allow them to reach their full potential while also thriving in their own lives. Unfortunately, it is clear that these students do not receive curricula targeting their abilities (J. R. Cross et al., 2022). A 2019 study of parent attitudes (n = 1440) to gifted education in Ireland found that most parents indicated dissatisfaction with the education their gifted child was receiving at school (74.1%), citing a lack of challenging learning materials, particularly at primary school level (J. R. Cross et al., 2019). The study found that, while Irish parents were in favour of gifted education generally and of access to more advanced materials, they did not support acceleration as a practice for gifted students. The J. R. Cross et al. (2019) study is the only other study which exists on parent perceptions of gifted education in Ireland.

Ireland’s education system is characterised by a prescriptive national curriculum (Kenny et al., 2020), which can prove difficult or frustrating for students whose needs extend beyond this. Recent research on differentiation practices in Irish primary schools reveals significant challenges in implementation. Hinch et al. (2024) found that, while teachers express commitment to differentiation, they often lack the time, resources, and training to implement it effectively, particularly for students with complex learning profiles. This finding has particular implications for twice-exceptional students, who require sophisticated differentiation that addresses both advanced ability and disability-related needs.

1.1.5. Research on Parent Perspectives and Advocacy

Internationally, a small but growing body of work demonstrates the unique and crucial perspective of parents in understanding the twice-exceptional population. They play a decisive role in pursuing recognition and appropriate support. Yet, their perspectives have historically been underrepresented in the literature (Dare & Nowicki, 2015). The existing research consistently highlights parents as the first to notice their children’s uneven development and as central advocates for dual recognition (Besnoy et al., 2015; Guilbault et al., 2024). Families are often the first to recognise their children’s frustrations and differences, often as early as age two (Dare & Nowicki, 2015; Mollenkopf et al., 2021). Parents are also the primary initiators of referrals for gifted screening and special education, and serve as critical advocates (Mun et al., 2021).

Other research confirms the dual nature of advocacy for parents of twice-exceptional learners. Besnoy et al. (2015) described how these parents seek disability-related supports while also protecting opportunities to develop giftedness.

Beyond advocacy, studies also document the emotional complexities of parenting twice-exceptional children. Matthews et al. (2014) found that some parents emphasised their child’s disability while downplaying giftedness, reflecting the deficit orientation of many educational systems. Similarly, Willard-Holt et al. (2013) observed that support for twice-exceptional learners tended to prioritise remediation and accommodations rather than the cultivating their strengths. Specialised subgroups of twice-exceptional learners highlight further challenges. Madaus et al. (2022) reported that families of twice-exceptional children with autism valued individualised, interest-based learning opportunities but were concerned about persistent difficulties in social interactions, insufficient academic challenges, and inadequate transition planning for postsecondary pathways. These findings echo broader concerns across the literature that parents often perceive a mismatch between what schools provide and what their children require to thrive.

Taken together, this body of work positions parents as critical interpreters and advocates of their children’s paradoxical profiles, often serving as the first to recognise both gifts and disabilities. As noted in the literature, most empirical work on twice exceptionality has examined giftedness or disability in isolation, with comparatively little attention to the intersection of the two, particularly from the perspective of families themselves. This gap underscores the need for more research centred on parents’ experiences, especially in under-studied contexts such as Ireland.

1.2. Research Gap and Study Rationale

Findings from the prior literature underscore the importance of parent perspectives, yet they also reveal that such perspectives remain underrepresented globally and that they are absent in the Irish context. This dearth of Irish-focused research represents a significant gap. Understanding parent perspectives of twice-exceptional children in Ireland is essential not only for supporting families more effectively, but also for informing the development of appropriate educational strategies and recognising the unique challenges these families face. Such insights are crucial for policymakers and educators in a system where twice-exceptional students remain largely invisible.

The present exploratory mixed-methods study addresses this gap by focusing on the perspectives of Irish parents of twice-exceptional children enrolled in CTYI. It provides descriptive information on the common disabilities of CTYI students aged 6–12 who are twice-exceptional. It investigates (a) how many hours per week of specialised services students receive for both their advanced learning needs and their areas of disability or learning difference, if any, and whether these vary by school type; (b) parents’ satisfaction with gifted and special education services provided at school, including potential differences based on school type. By examining these dimensions, the study provides one of the first empirical accounts of how families in Ireland experience both gifted and special education services for their twice-exceptional children. In doing so, it not only fills a critical gap in the Irish context but also contributes to the international literature on the role of parents as advocates, evaluators, and essential partners in shaping effective services for twice-exceptional learners. The main research question of this study was the following? “What are parents’ perceptions of the educational experiences of their twice-exceptional child?” The following research questions guided this study:

- RQ1

- What are the most prevalent learning disabilities reported by parents of twice-exceptional students aged 6–12 who attend CTYI?

- RQ2

- How many hours per week of specialised education services do CTYI-enrolled twice-exceptional students aged 6–12 receive at school in Ireland for their (a) advanced learning needs and (b) their areas of disability or learning difference, if any?2a. Are there differences based on school type?

- RQ3

- How satisfied are parents of CTYI-enrolled twice-exceptional children with the (a) gifted education services and (b) special education services provided at school, if any?3a. Are there differences based on school type?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

This study employed an exploratory mixed-methods design to examine the perspectives of parents of twice-exceptional children attending a summer enrichment programme in Ireland. A mixed-methods research design was chosen to yield additional insights beyond the information that could be provided by each approach singularly (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). Online surveys were used with both open-ended and Likert scale items to solicit their opinions regarding the quality and level of services their child receives in school for their gifts and for their disabilities.

2.2. Participants and Recruitment

Participants for this study included a purposeful sampling of 232 parents of twice-exceptional children between the ages of 6 and 12 who attended a summer programme at CTYI based within Dublin City University. The research team reviewed student applications files and identified 695 possible participant families that met the study eligibility criteria: (1) their child was between the ages of 6 and 12; (2) their child had been formally identified as both gifted (e.g., by psychological testing or though the CTYI talent search testing) and as having a disability. Of the 695 families contacted, 232 completed the survey (response rate 33.4%).

The demographic profiles of the participating twice-exceptional children are presented in Table 1. Children’s ages ranged from 6 to 12 years (M = 10.03, SD = 1.57). On average, participants lived in households with approximately one–two siblings under the age of 18 (M = 1.48, SD = 1.01). Parents reported that, on average, fewer than one sibling per household was also identified as gifted (M = 0.49, SD = 0.71) or as having a special education need (M = 0.57, SD = 0.76). Reports of siblings identified as both gifted and with a special learning need (twice exceptional) were less common, with a mean of 0.34 siblings (SD = 0.62).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants’ children.

Information on school context was also collected. In Ireland, the Delivering Equality of Opportunity in Schools (DEIS) programme is the primary national initiative designed to address educational disadvantage, providing resources to schools that typically serve a large proportion of students from low socioeconomic backgrounds (Fleming & Harford, 2023). Regarding school context, most children did not attend a school classified as DEIS (93.5%, n = 217), whereas a small minority were enrolled in a school classified as DEIS (6.5%, n = 15).

The Centre for Talented Youth Ireland (CTYI), based at Dublin City University, is the only organisation which is specifically focused on serving gifted children and adolescents nationally. CTYI aims to provide a highly stimulating academic experience in an atmosphere that is supportive of both social and emotional needs. Currently, CTYI serves approximately 6000 students per year in the main hub at Dublin City University and in regional centres across Ireland (Dunne et al., 2025). CTYI does not receive external government funding. Students are identified for the programme using the Talent Search process or via an educational psychologist.

2.3. Instrument and Data Collection

CTYI regularly conducts evaluations of its courses and programmes using various surveys. An online survey with 32 items was developed that included multiple choice, 5-point Likert scale items, and open-ended response questions asking participants to evaluate the gifted education and special education services their child receives in school and at CTYI. Questions included age of child, family composition, sibling information, type of school attended, types of learning disabilities, satisfaction with gifted education and special education services at school, and total number of hours of service at school, if any. The survey was designed by the research team to collect information that could be used to improve CTYI programmes and identity teacher training needs and parent education topics. The survey was pilot tested by content experts first, edited for clarity, and then distributed for data collection. The items were designed to solicit parent input and feedback on the strengths and weaknesses of the services their child receives in school. For example, participants were asked to rate their level of satisfaction with the special education services their child receives in school, if any, with 1 = very dissatisfied and 5 = very satisfied. Participants could skip any item. The survey was sent as a protected link to individuals via email and they completed the surveys at home during the summer of 2025. Parents previously opted-in to receive communication and surveys from CTYI. Participants provided informed consent by clicking on the appropriate box before completing the survey.

2.4. Data Analysis

Although personally identifying information was not specifically collected, some participants included potentially identifying information in response to the open-ended questions such as details about their child. The research team anonymised those responses. The collected data were input in IBM SPSS Statistics (version 31) for analysis. Descriptive analysis was carried out on all the quantitative items. Data were further analysed by carrying out independent samples t-tests (Welch’s t-test) after conducting Levene’s test for equality of variances, Mann–Whitney U tests, and simple linear regressions to evaluate group differences in responses. Chi-squared tests of independence and logistic regression were carried out between certain variables to determine whether there were relationships. Qualitative responses were used illustratively to support the quantitative results.

3. Results

Results are organised according to the study’s research questions, examining (RQ1) the most prevalent learning disabilities among participating students, (RQ2) the number of hours of specialised educational services received by students for both their giftedness and learning disabilities, and (RQ3) overall parent satisfaction with the services provided at school.

3.1. What Are the Most Prevalent Learning Differences or Disabilities Reported by Parents of 2E CTYI Students Ages 6–12? (RQ1)

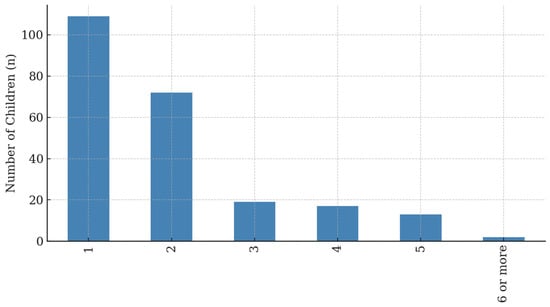

Almost half of participants’ children had been diagnosed with one learning difference or disability (n = 109, 47%) and about a third had been diagnosed with at least two (see Table 2 and Figure 1).

Table 2.

Total number of identified disabilities for participants’ children.

Figure 1.

Distribution of number of disabilities per child (n = 232).

One survey item asked the participants to indicate what learning differences or disabilities their child had been formally diagnosed with. They could check more than one and were provided space to write in any other form of disability not listed. Thirty-eight parents (16.4%) opted to write in responses to this item. Several noted that diagnoses were in process or suspected. The two most frequently noted learning differences in written responses were dyspraxia (n = 7) and dysgraphia (n = 5). Other notable mentions include ADHD diagnosis pending or suspected (n = 4), autism suspected or pending diagnosis (n = 3), and hypermobility disorders affecting handwriting or fine motor skills (n = 3).

Some of the written comments could be classified under developmental coordination disorder (DCD), such as: “suspected dyspraxia,” “motor coordination issues,” “clumsy,” “primitive reflexes movement group.” Additionally, several comments could be categorized under speech and language disorders, including “speech delay,” “verbal dyspraxia,” “language delay,” and “apraxia.” The research team assumed that these were noted as pending or suspected diagnoses when they opted to write in rather than select from the list provided. See Appendix A for a table listing the responses provided for “other” and frequency count.

Regarding the specific types of disabilities that parents reported their child had been diagnosed with along with giftedness, autism was the most prevalent difference reported (n = 139, 59.9%) followed by attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD; n = 74, 31.9%) and dyslexia (n = 62, 26.7%), as displayed in Table 3.

Table 3.

Frequencies for reported disabilities.

3.2. How Many Hours per Week of Specialised Education Services Do CTYI 2E Students Aged 6–12 Receive at School for Their Advanced Learning Needs and for Their Areas of Disability or Learning Difference, if Any? (RQ2)

3.2.1. Special Education Services

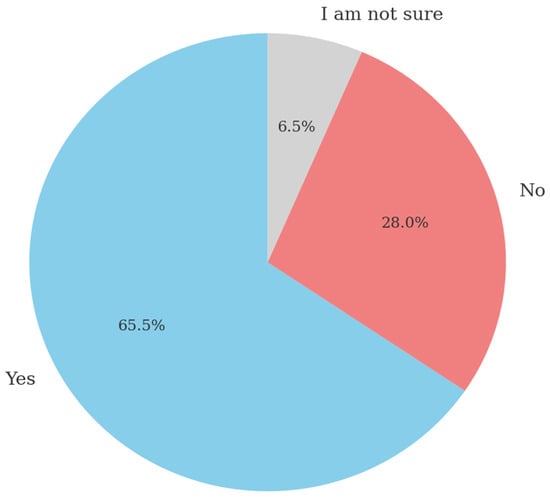

Participants were asked whether their child received special education (SEN) services during the school day. In response to this question, 152 parents (65.5%) selected “yes”, confirming that their child received special education services at school, 65 (28%) responded no, and 15 (6.5%) were not sure (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Does your child receive special education services at school? (n = 232).

Participants who selected “yes” were asked to report approximately how many hours per week their child spent in special education (SEN) interventions. Total weekly SEN support was most commonly 1–2 h per week (63.2%), followed by 3–5 h (30.9%), 6–10 h (2.0%), and more than 10 h (2.0%). Using category midpoints to approximate continuous hours (0, 1.5, 4, 8, and 12 h for >10), the estimated mean SEN support was 3.12 h per week, with a median of 1.5 h and a modal category of 1–2 h per week. These mean and median values should be understood as approximations derived from interval midpoints, particularly for the open-ended >10 h category. Results are displayed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Total hours per week of special education services received in school (n = 152).

3.2.2. Special Education Total Hours by School Type

Group differences by DEIS status (0 = non-DEIS, 1 = DEIS) were evaluated using independent-samples t tests (Welch’s t-test) and supplemented with Mann–Whitney U tests due to small DEIS subsamples (see Table 5 and Table 6). Among students who received SEN services (n = 152) and reported a ‘valid hours’ category, Welch’s t-test indicated a significant difference in weekly service hours between DEIS (M = 2.75, SD = 0.79, n = 10) and non-DEIS students (M = 2.64, SD = 2.01, n = 142), t(18.78) = 2.94, p = 0.0004.

Table 5.

Welch’s t-test comparing weekly special education service hours by DEIS status.

Table 6.

Mann–Whitney U results comparing weekly SEN service hours by DEIS status.

However, a Mann–Whitney U test did not yield similar results, U = 531.5, p = 0.118, likely due to small group size and skewed distributions. A simple linear regression (hours ~ DEIS) also showed a non-significant DEIS coefficient, b = −0.014, p = 0.168. Taken together, there is inconclusive evidence that DEIS status predicted the number of weekly SEN service hours among those receiving services. Given the small DEIS subgroup in this analysis, these estimates should be interpreted with caution.

3.2.3. Gifted Education Services

Next, parents were asked about their child’s specific gifted education (GT) services received in school, if any (e.g., subject acceleration, curriculum compacting, enrichment, pull-out or resource class), and the frequency. Most students were not receiving any special services for their advanced learning needs (n = 170, 73.3%), 49 children received some services (21.1%), and 5.6% (n = 13) of parents were not sure whether their child was receiving these services. Of those who reported their child was receiving specialised gifted education services at school, the most common weekly service amount was 1–2 h per week (65.3%), followed by 3–5 h (18.4%), 6–10 h (4.1%), and more than 10 h (2.0). These estimates are based on the subset of parents who both indicated their child received gifted services and provided an ‘hours’ category (n = 44). Five additional parents indicated their child received gifted services but were unsure of the number of hours per week. The mean for the group receiving gifted services was 2.55 h per week (SD = 2.17); see Table 7.

Table 7.

Total hours per week of gifted education services received in school (n = 44).

3.2.4. Does DEIS School Status Affect Whether 2E Students Receive Gifted Education Services in School?

A chi-square test of independence indicated no association between DEIS school status and receipt of gifted services, χ2(1) = 0.05, p = 0.808 (see Table 8). A logistic regression predicting receipt of gifted services from DEIS status likewise found no significant effect: OR = 1.42, 95% CI [0.42, 4.74], p > 0.05. Thus, twice-exceptional children attending schools classified as DEIS did not differ from non-DEIS peers in the likelihood of receiving gifted services in school. There were no statistically significant differences in gifted education service hours by DEIS status.

Table 8.

Chi square test of independence (n = 232).

3.2.5. Among Students Who Do Receive Gifted Services, Does DEIS Status Affect How Many Hours They Receive?

Group differences by DEIS status (0 = non-DEIS, 1 = DEIS) were evaluated using independent-samples t tests (Welch’s t-test) and supplemented with Mann–Whitney U tests due to small DEIS subsamples (see Table 9 and Table 10). Among students who received any gifted services (n = 49) with a reported ‘valid hours’ category, Welch’s t-test indicated no significant difference in weekly service hours between DEIS (M = 2.13, SD = 1.25, n = 4) and non-DEIS students (M = 2.59, SD = 2.25, n = 40), t(5.22) = 0.64, p = 0.547.

Table 9.

Welch’s t-test comparing weekly gifted service hours by DEIS status.

Table 10.

Mann–Whitney U comparing weekly gifted service hours by DEIS status.

A Mann–Whitney U test yielded similar results, U = 83.5, p = 0.875. A simple linear regression (hours~DEIS) also showed a non-significant DEIS coefficient, b = −0.46, p = 0.690. Taken together, there was no evidence that DEIS status predicted the number of weekly gifted service hours among those receiving services. Given the small DEIS subgroup in this analysis, these estimates should be interpreted with caution.

3.3. Parent Satisfaction with School-Based Services

Parents’ satisfaction with the school-based services provided to their twice-exceptional children was examined. Specifically, satisfaction ratings were analysed separately for gifted education services and for special education services, providing insight into how parents perceive the adequacy of support structures across both areas of need.

3.3.1. Parent Satisfaction with Their Child’s Special Education Experiences in School

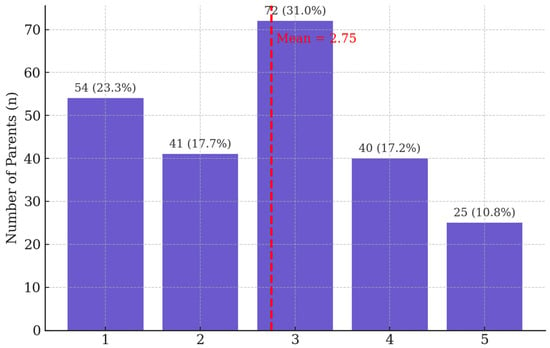

The mean rating on a 5-point Likert Scale for the question about satisfaction with special education services was 2.75 (SD = 1.29, n = 232), 95% CI [2.58, 2.92], indicating a lean toward the dissatisfied range. Most participants selected “neutral/neither satisfied nor dissatisfied (n = 72, 31%), followed by “very dissatisfied” (n = 54, 23.3%). Only 25 parents (10.8%) selected “very satisfied.” The standard deviation (1.29) shows a wide spread of opinions with some parents reporting feeling very dissatisfied and a smaller portion feeling highly satisfied; see Figure 3 for the results.

Figure 3.

Parent satisfaction with their child’s special education services (n = 232): 1 = very dissatisfied, 5 = very satisfied. Participants could skip this item if their child did not receive special education services.

Group differences by DEIS status (0 = non-DEIS, 1 = DEIS) were evaluated using independent-samples t tests (Welch’s t-test) and supplemented with Mann–Whitney U tests due to small DEIS subsamples (see Table 11 and Table 12). Welch’s t-test indicated no significant difference in parent satisfaction with their child’s special education services between DEIS (M = 2.87, SD = 1.060, n = 15) and non-DEIS students (M = 2.74, SD = 1.302, n = 217), t(17.06) = −0.450, p = 0.659.

Table 11.

Welch’s t-test comparing parent satisfaction with SEN services by DEIS status.

Table 12.

Mann–Whitney U comparing parent satisfaction with SEN services by DEIS status.

A Mann–Whitney U test obtained similar results, U = 1722.5, p = 0.698. A simple linear regression also showed a non-significant DEIS coefficient, b = 0.129, p = 0.707. This indicates that there is no evidence that DEIS status predicted how satisfied parents are with the special education services their child receives. Given the small DEIS subgroup in this analysis, these estimates should be interpreted with caution.

3.3.2. Parent Satisfaction with Their Child’s Gifted Education Experiences in School

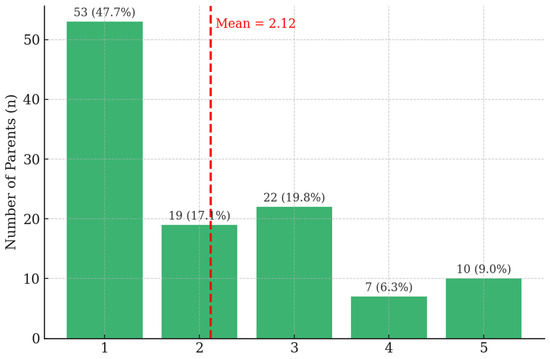

Parents reported generally low satisfaction with the specialised gifted education services their children received at school. When asked to rate their level of satisfaction with gifted education services, most participants (n = 53, 47.7%) reported they felt “very dissatisfied” and only 10 parents (9%) felt “very satisfied.” The mean was 2.12 (SD = 1.32), which was just above “dissatisfied” and well below the neutral option. The standard deviation (1.32) indicates considerable variation; however, 64.8% were either dissatisfied or “very dissatisfied” compared to only 15.3% feeling “satisfied” or “very satisfied”; see Figure 4 for these results.

Figure 4.

Parent satisfaction with their child’s gifted education services (n = 111): 1 = very dissatisfied, 5 = very satisfied.

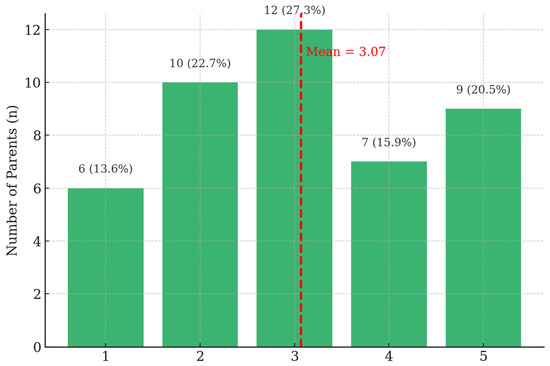

Upon closer examination, it was noted that 111 participants answered this survey item instead of skipping it if their child did not receive gifted education services. Therefore, the analysis was run again looking at only those who selected “yes” to the question about whether their child received gifted education services at school. Results for this group (n = 44) paint a different picture (See Figure 5). In this subgroup, satisfaction ratings averaged 3.07 (SD = 1.34, n = 44), 95% CI [2.67, 3.47]. These ratings indicate that parents’ views of gifted services were, on average, near the neutral midpoint, with some parents reporting very low satisfaction and others expressing high satisfaction.

Figure 5.

Parent satisfaction with their child’s gifted education services (n = 44): 1 = very dissatisfied, 5 = very satisfied.

The mean (3.07, SD = 1.34), represented by the red dashed line in Figure 5, reflects a more balanced distribution. While the average response is slightly above neutral, there is still considerable spread. For this group, 36.3% felt either “somewhat” or “very” dissatisfied with gifted education services, 27.3% felt “neither satisfied nor dissatisfied”, and 36.4% indicated they were either “somewhat” or “very satisfied” with their child’s gifted education services at school.

Group differences by DEIS status (0 = non-DEIS, 1 = DEIS) were evaluated using independent-samples t tests (Welch’s t-test) and supplemented with Mann–Whitney U tests due to small DEIS subsamples (see Table 13 and Table 14) to investigate whether there were differences in parent satisfaction with their child’s gifted services. For these tests, only parents of recipients of gifted services were included (n = 44). Welch’s t-test indicated no significant difference in parent satisfaction with their child’s school gifted services between DEIS (M = 2.75, SD = 0.957, n = 4) and non-DEIS students (M = 3.10, SD = 1.374, n = 40), t(4.35) = 0.67, p = 0.539.

Table 13.

Welch’s t-test comparing parent satisfaction with GT services by DEIS status.

Table 14.

Mann–Whitney U comparing parent satisfaction with GT services by DEIS status.

A Mann–Whitney U test obtained similar results: U = 67.5, p = 0.622. A simple linear regression also showed a non-significant DEIS coefficient: b = −0.350, p = 0.623. This indicates that there is no evidence that DEIS status predicted how satisfied parents are with the gifted services their child receives from their school. Given the small DEIS subgroup in this analysis, these estimates should be interpreted with caution.

Next, we compared parent satisfaction regarding special education and gifted education services received at school (see Table 15).

Table 15.

Satisfaction with gifted education and special education services in school (all).

All participants (n = 232) responded to the question asking them to rate their satisfaction with their child’s special education services, even if they later reported that their child was not currently receiving services. Eighty participants (30.5%) responded to this item instead of skipping it. Similarly, 111 participants also responded to the item about satisfaction with gifted education services, even though only 44 later reported that their child was actually receiving gifted education services in school. We used these results to compare general satisfaction between special education and gifted education services in schools, since parents felt strongly enough to respond either way, indicating their feelings about the provision of related services, or lack thereof.

When comparing only the families whose children were reportedly receiving services in school, they were still overall more satisfied with the special education services compared to gifted education services. Parents of children who receive SEN services rated satisfaction at M = 3.15 (SD = 1.16), while those receiving gifted services rated it at M = 3.07 (SD = 1.34). However, the difference is small and not statistically significant (p = 0.69, Cohen’s d = 0.07). Both groups centre around 3 on the 5-point scale, with similar variability. The 95% confidence intervals overlap substantially (SEN: 2.97–3.34; GT: 2.66–3.47), confirming no meaningful difference between parent satisfaction with special education vs. gifted services among recipients of such services in the schools. See Table 16 for a comparison between parent satisfaction with special education and gifted education service for parents who selected “yes”, indicating their child did receive such services at school.

Table 16.

Satisfaction with gifted and special education services in school (“Yes” only).

Using an open-text box, participants were also asked “What other gifted education services would you like to see offered for your child at school, if any?” This item received 209 responses, the majority of which emphasised the overall lack of services offered. One parent wrote, “my child doesn’t receive this at his school, so it would be great if he were challenged more in the school setting. He tells me he is bored at school and doesn’t like it” (R086, parent of male child, age 10). Another stated, “I would like to see any support or recognition of giftedness” (R119, parent of female child, age 10).

4. Discussion

This exploratory mixed-methods study aimed to investigate parent perspectives of the experiences of their twice-exceptional children enrolled in primary schools in Ireland. We also explored potential variations in these results, in particular whether school type (DEIS or non-DEIS) affected the results. Overall, the findings indicate that students are receiving significantly fewer services for their gifted ability than they are for their special education learning needs, regardless of school type. Parents were also, on average, more dissatisfied with their child’s access to gifted education services than with their access to special education services.

4.1. Types of Disabilities and Parent Awareness

The prevalence patterns observed in this study reveal important insights about the twice-exceptional CTYI student population in Ireland. Autism spectrum disorder emerged as the most common co-occurring condition (59.9%), followed by ADHD (31.9%) and dyslexia (26.7%). This distribution aligns with international research, suggesting that neurodevelopmental conditions, particularly those affecting social communication and executive functioning, frequently co-occur with giftedness (Foley-Nicpon et al., 2011). The high rate of autism among gifted students may reflect both genuine prevalence and the possibility that cognitive strengths can mask autistic traits, leading to later or more complex identification processes.

Notably, over half of the children were reported to have two or more disabilities, with some families reporting up to six or more co-occurring conditions! This complexity underscores the multifaceted nature of twice exceptionality and suggests that many of these students require coordinated, multi-disciplinary support that addresses the interaction between their various learning profiles. The presence of multiple diagnoses may also complicate service provision, as schools must navigate overlapping or sometimes conflicting accommodation needs.

Several of the written responses to the item asking about their child’s diagnosed learning differences or disabilities mentioned pending or suspected diagnosis. Since the students were as young as age 6, it is likely that these children may still be in the identification or referral and screening process or may receive a formal diagnosis later. This is an important finding because it shows that some parents suspect their child may have unique learning needs from an early age, and need guidance, support, and information from professionals to support their child before and during the identification process. For younger twice-exceptional students for whom educational services are not yet available, their needs may not be fully met by the school system.

Because several parents also mentioned conditions in the “other” open response item that were already on the selection list, this also shows that parents may not be fully aware of the language and terminology used by professionals. For instance, dyspraxia falls under the classification of developmental coordination disorder (DCD) according to the DSM-5; participants may have written this in the “other” section because their child’s diagnosis was pending. Others indicated giftedness under the category of learning disability, for example, writing in “high IQ (98th–99th percentile).” The terminology confusion evident in parent responses, such as conflating giftedness with learning disability or using outdated diagnostic terms, points to a critical need for parent education and clearer communication from professionals. When parents lack familiarity with diagnostic frameworks like the DSM-5 or educational classification systems, they may struggle to advocate effectively for their children or understand the services available. This knowledge gap may be particularly pronounced for twice-exceptional students, whose profiles defy simple categorization and require parents to navigate both special education and gifted education systems simultaneously.

4.2. Gifted and Special Education Services Received

Two thirds of parents stated that their child received services at school for their disability. In contrast, most parents reported that their child received no services for their advanced learning needs. Unfortunately, it often seems to be the case that twice-exceptional children will receive support that focuses only on remedial intervention, rather than a strengths-based approach which can factor in areas in which they are appropriately challenged (Gierczyk & Hornby, 2021). This may be a result of a child’s disabilities having masked their abilities (King, 2005), or of priorities within that school environment. Schools, teachers, special education providers, and parents must be mindful that these students require and deserve educational approaches that address their exceptional abilities alongside their learning disabilities.

The stark disparity between special education and gifted service provision is particularly concerning for twice-exceptional students. While 65.5% received special education services, only 21.1% received gifted education services—a threefold difference in access. These results echo prior findings by Foley-Nicpon et al. (2011), LeBeau et al. (2025), and García-Martínez et al. (2021). Moreover, among those receiving services, the mean hours were comparable, suggesting that, when gifted services are provided, they receive similar time allocations. However, the critical issue is not the intensity of services among recipients, but rather the dramatically lower likelihood of receiving gifted services at all. This pattern suggests a systemic prioritisation of deficit-based intervention over strength-based enrichment, which may leave twice-exceptional students’ advanced learning needs largely unaddressed.

It was surprising that multiple parents were unsure whether their child was receiving either special education or gifted services at all, raising questions about communication between schools and families. These findings are similar to those presented in prior research by Blue-Banning et al. (2004). Among the parents who confirmed their child did receive gifted services, a handful could not estimate the weekly number of hours, suggesting possible inconsistency in service delivery or a lack of transparency about programming. This uncertainty may reflect informal or sporadic enrichment activities that are not clearly defined as “gifted services,” or it may indicate insufficient communication from schools about the nature and extent of support provided.

Research focusing on special educational needs in schools classified as DEIS has indicated that the schools classified as DEIS often have higher numbers of students with special education needs, in addition to being more likely to have ASD classes in comparison to non-DEIS settings (Banks et al., 2015; Cahill, 2021). Given traditionally higher rates of need in schools classified as DEIS, it is perhaps interesting that, in this study, there was little difference in the hours provided to twice-exceptional students. However, the lack of association between DEIS status and receipt of gifted services may be more revealing. This finding suggests that gifted education services are equally scarce across socioeconomic contexts—a pattern that could reflect either inequity in resource allocation or systemic underinvestment in gifted programming, regardless of school resources.

It is possible that the additional funding provided to schools classified as DEIS accounts for the comparable special education hours provided; however, further research is needed with larger numbers of DEIS participants in order to determine whether this is the case, or whether the parents financially positioned to send their children to gifted programmes outside of school are better able to advocate for their child’s special education needs than others in schools classified as DEIS. The small DEIS subsample in this study (n = 10) limits the generalizability of these findings and highlights the need for targeted recruitment of DEIS-enrolled families in future research. It is also worth considering that parents who can afford external gifted programming (such as CTYI) may possess greater educational capital and advocacy skills, potentially enabling them to secure more school-based services, regardless of DEIS status. This selection bias effect may obscure true disparities in service access between DEIS and non-DEIS in the broader population of twice-exceptional students.

The concentration of service hours in the 1–2 h per week category for both special education and gifted services raise questions about dosage and effectiveness. While even modest interventions can be beneficial, research on gifted education suggests that brief weekly pull-out sessions may be insufficient to meaningfully differentiate curriculum or provide appropriate challenge (García-Martínez et al., 2021). For twice-exceptional students who require both specific supports and advanced education services, the limited time allocation may leave significant educational needs unmet. Furthermore, only a handful of special education recipients and gifted service recipients received more than 10 h per week, indicating that intensive support models are rare, even for students with complex profiles involving multiple disabilities. It is noteworthy that half of this sample had two or more diagnosed conditions. The limited provision of specialised interventions for twice-exceptional students in Ireland reflects a broader international pattern. García-Martínez et al.’s (2021) systematic review found that educational attention to gifted students has not been well-established globally, suggesting that the challenges Irish parents report is not unique but part of systemic gaps in how educational systems serve students with exceptional learning needs.

4.3. Parent Satisfaction with Gifted Education and Special Education Services in Ireland

Within this study, parent dissatisfaction with gifted services in Irish schools was evident. In contrast to earlier findings by Matthews et al. (2014), parents in the present study did not prioritize their twice-exceptional child’s special education need over their giftedness. On average, parents were not satisfied with the gifted education services their child received at school. This is perhaps not surprising, since most respondents indicated their child received no services which addressed their advanced learning needs. The concentration of “very dissatisfied” responses is particularly noteworthy and suggests that the absence of gifted services is not merely a missing service that families just accept, but an active source of frustration for families. This dissatisfaction may be compounded for twice-exceptional students, whose disabilities are visible and addressed while their strengths remain unrecognised. The psychological impact of this imbalance, where children receive the message that they need “fixing” but not enrichment, may contribute to the low self-concept and underachievement documented in twice-exceptional populations (Foley-Nicpon et al., 2011; Guilbault & McCormick, 2023; Reis et al., 2014).

Participant write-in responses related to parent dissatisfaction with gifted education services (or lack thereof) in schools were largely similar to those received in the only other study on parent attitudes to gifted education in Ireland (J. R. Cross et al., 2019); here, the authors found that the majority of parents (74.1%) were unhappy with the level of gifted services their child received. Parents in that study also noted the absence of appropriate challenging academic material, in particular at primary school (J. R. Cross et al., 2019), which parents in the present study also cited as an issue. The persistence of parent concerns across six years (from 2019 to 2025) and across different samples suggests systemic rather than isolated problems with gifted education provision in Ireland. The fact that parents of twice-exceptional children express similar dissatisfaction as parents of gifted children without disabilities indicates that the challenges are not unique to the twice-exceptional population but perhaps reflect broader gaps in Ireland’s educational response to giftedness. However, for twice-exceptional students, the stakes may be higher: boredom and lack of challenge can exacerbate behavioural and emotional difficulties associated with conditions like ADHD and autism, creating a negative cycle where the unmet needs of gifted children intensify their disability-related challenges.

The overall neutral mean for special education services contrasts sharply with the gifted services, where “very dissatisfied” was the most common response, suggesting qualitatively different patterns of dissatisfaction. For special education services, the distribution is more evenly spread across the satisfaction spectrum, which may reflect variability in service quality, appropriateness, or fit with individual children’s needs. Responses to the open-ended item “What other special education services would you like your school to provide for your child, if any?” were mixed, with 204 parents writing in responses. The most frequently appearing term was “support”, with parents desiring increased support for their twice-exceptional child’s special education needs, as well as teacher education and training. One parent wrote, “It all relates back to the lack of giftedness support for him, if there was an appropriate education for him all the autistic challenges would be less challenging” (R168, parent of male child, age 9). This parent’s observation that appropriate gifted education services could reduce their child’s autism-related challenges reflects a sophisticated understanding of the interconnected nature of twice exceptionality. When gifted students are appropriately challenged and engaged, behavioural issues often diminish (Reis et al., 2025). Conversely, when advanced learners are chronically under-stimulated, they may exhibit inattention, restlessness, or disruptive behaviour that can be misattributed to or conflated with ADHD or autism symptoms.

4.4. Limitations

This study is the first to investigate parents’ perceptions of education for twice-exceptional children in Ireland; however, as an exploratory study that relied on a convenience sample of families with children attending a special program for the gifted, results may not be generalised to other twice-exceptional students in Ireland or in other countries. These families were either referred to CTYI by their schools or sought out CTYI on their own to provide enrichment for their child’s talents and to find like-minded peers for their children; thus, the results may be biased or skewed. Another limitation is that we only surveyed parents of current summer programme students. Future research should include student and alumni perspectives as well as parents of other twice-exceptional children in Ireland who qualify for CTYI programmes but who, for various reasons (e.g., financial, geographical, medical, transportation), are unable to participate.

4.5. Implications for Future Research

The study’s findings highlight critical gaps in the understanding and support of twice-exceptional students, particularly within the Irish context. Future research must move beyond the observation of service disparity and investigate the systemic factors at play. The most pressing issue for future research is to build an understanding of how schools manage the dual needs of twice-exceptional students. The current system appears to prioritise one need (disability) over the other (giftedness) due to legislation and funding differences. Research should investigate how the process of identifying a special educational need, which is legally defined and supported, overshadows the identification of giftedness, which is not. This can result in a student’s giftedness being masked by their disability, or vice versa. A key area of inquiry is to examine the lived experiences of twice-exceptional students and their families to understand the practical impact of this “either/or” approach to their education.

While Ireland has guidelines for exceptionally able students, they are often not fully implemented in schools, and there is an absence of specific training for teachers in this area. Research is needed to examine the gap between existing policy and day-to-day practice. This research could identify what specific professional development approaches and resources would be most effective for teachers to help them support the full spectrum of a twice-exceptional student’s need.

4.6. Recommendations for Practice

Based on these findings, it is clear that addressing the needs of twice-exceptional students requires a practical and policy-driven approach that integrates both gifted and special education services. To address the disconnect, schools should move away from treating gifted and special education as separate, competing domains, or ignoring gifted needs altogether. A core recommendation is to develop comprehensive Student Support Plans, (similar to the individualised education plans (IEPs) used in other countries) for every twice-exceptional student that explicitly embed giftedness alongside special education needs into the plan, rather than focusing solely on the child’s special educational challenges. This would incorporate parent (and student) input and integrate the goals and services from both perspectives, creating a single, comprehensive document that ensures a student’s strengths are nurtured while their challenges are accommodated. This formal process would provide a clear structure for service delivery, addressing parental concerns about inconsistent support and poor communication.

Critically, the parents in this study reported significant gaps in their knowledge about what services their children were receiving, the frequency of these services, and their quality. A formalised Student Support Plan process would address these concerns by providing transparent documentation of services, clear communication protocols between schools and families, and regular review mechanisms. While this approach would require policy development given that giftedness is not currently recognised within Ireland’s special education framework, such formal processes could provide clearer structures for service delivery, addressing parental concerns about inconsistent support and poor communication.

A fundamental step lies in advocating for a cultural and legal shift. Schools, parents, and advocacy groups should work together to lobby the Department of Education for dedicated funding and services for this oft-ignored educational need. While giftedness is not currently recognised within Ireland’s special educational needs framework, formal recognition would put gifted and twice-exceptional students on equal footing with their peers who have additional educational needs, ensuring that their unique profile is supported by a more robust system than that which exists at present.

5. Conclusions

Parents act as central advocates for the recognition of their children’s twice exceptionality (Guilbault et al., 2024), noticing early stages of frustration (Dare & Nowicki, 2015) when needs are not being adequately met. Parents also play a critical role in the early identification of their children’s abilities (Mollenkopf et al., 2021), even if they are unfamiliar with the label ‘twice exceptional’ (Khan et al., 2025). In this study, parents expressed dissatisfaction with both special education and gifted education services, although dissatisfaction for gifted services was markedly higher. This is unsurprising given that the study also found a significant difference between levels of services offered and hours of service, with many twice-exceptional children receiving no gifted education services. In qualitative feedback given, parents described how special education services typically focused on weaknesses rather than cultivating their twice-exceptional child’s strengths. Collectively, these findings highlight parents as critical interpreters and advocates for twice-exceptional children, pointing to a need for further research in Ireland and reinforcing the need for greater integration of gifted education into Irish schools. While CTYI provides valuable enrichment, parents’ concerns point to the greater need of a systemic approach, which includes teacher education and professional development and policy reform. These factors would contribute to a more inclusive learning environment for twice-exceptional students, which supports them academically and socially.

One parent offered the below response to an item on the additional services desired, which illustrates the need for an integrated approach to support twice-exceptional children:

[I would like to see] a community approach. Given the situation that schools find themselves in regarding the high level of needs in schools, partnership with parents and other interested and vetted community members may allow for the development of a simple gifted program that develops over the years.(R070, parent of female child, age 8.)

This parent’s vision of collaborative, community-based support reflects both the resourcefulness of families navigating an inadequate system and the potential for creative solutions when schools, parents, and communities work together. The voices of parents in this study make clear that twice-exceptional children in Ireland are waiting—waiting for recognition, waiting for challenge, waiting for educational experiences that honour the full complexity of their learning profiles. Addressing their needs is not only a matter of educational equity but an investment in the potential of students whose unique combination of strengths and challenges positions them to make distinctive contributions to society.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, O.D., C.O. and K.M.G.; methodology, O.D. and K.M.G.; formal analysis, K.M.G., L.H. and O.D.; investigation, O.D.; resources, C.O.; data curation, K.M.G. and O.D.; writing—original draft preparation, O.D., K.M.G., L.H. and A.R.; writing—review and editing, O.D., K.M.G. and L.H.; supervision, O.D. and C.O.; project administration, O.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research was conducted in accordance with the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (2018) and guided by the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki, particularly those relating to respect for persons, informed consent, and the protection of vulnerable participants. Data for this study was collected during a routine feedback survey, which CTYI uses for programme evaluation, and which does not require ethical approval. Consent was required from each participant, and this included a stipulation that data may be used for research purposes.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the parent participants who contributed to the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CTYI | Center for Talented Youth, Ireland |

| 2E | Twice-Exceptional |

| DEIS | Delivering Equality of Opportunity in Schools |

| SEN | Special Education Needs |

Appendix A

Frequency distribution of learning disabilities provided in “Other” comments section.

| Category | Frequency |

| Dyspraxia (including suspected/verbal) | 7 |

| Dysgraphia (including motor dysgraphia) | 5 |

| ADHD (suspected or pending diagnosis) | 4 |

| Autism (suspected or pending diagnosis) | 3 |

| Hypermobility disorders | 3 |

| PDA (Pathological Demand Avoidance) | 2 |

| Note/Comment only | 2 |

| Visual/Processing issues | 2 |

| Sensory issues | 2 |

| OCD (suspected) | 1 |

| Seizures (non-epileptic) | 1 |

| School refusal | 1 |

| Dyscalculia supports (no formal diagnosis) | 1 |

| High IQ | 1 |

| Neurodiversity (not diagnosed as ADD) | 1 |

| No additional disability | 1 |

| Speech/Language delays | 1 |

References

- Abi Villanueva, S., & Huber, T. (2021). The issues in identifying twice exceptional students: A review of the literature. International Journal of Development Research, 9(9), 30101–30112. [Google Scholar]

- Asperger, H. (1944). Die “autistischen Psychopathen” im Kindesalter. Archiv für Psychiatrie und Nervenkrankheiten, 117(1), 76–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assouline, S. G., Colangelo, N., & Gross, M. U. (Eds.). (2015). A nation empowered: Evidence trumps the excuses holding back America’s brightest students (Vol. 2). Belin-Blank Center, College of Education, University of Iowa. [Google Scholar]

- Banks, J., Frawley, D., & McCoy, S. (2015). Achieving inclusion? Effective resourcing of students with special educational needs. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 19(9), 926–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besnoy, K. D., Swoszowski, N. C., Newman, J. L., Floyd, A., Jones, P., & Byrne, C. (2015). The advocacy experiences of parents of elementary age, twice-exceptional children. Gifted Child Quarterly, 59(2), 108–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blue-Banning, M., Summers, J. A., Frankland, H. C., Nelson, L. L., & Beegle, G. (2004). Dimensions of family and professional partnerships: Constructive guidelines for collaboration. Exceptional Children, 70(2), 167–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borland, J. H. (2004). Issues and practices in the identification and education of gifted students from under-represented groups (RM04186). University of Connecticut, The National Research Center on the Gifted and Talented. [Google Scholar]

- Brody, L. E., & Mills, C. J. (1997). Gifted children with learning disabilities: A review of the issues. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 30(3), 282–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahill, K. (2021). Intersections of social class and special educational needs in a DEIS post-primary school: School choice and identity. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 28(7), 977–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, M. R., Harradine, C. C., & King, E. W. (2005). The identification of students who are gifted and have learning disabilities: The twice-exceptional. National Research Center on the Gifted and Talented, University of Connecticut. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, J. R., Cross, T. L., & O’Reilly, C. (2022). Irish gifted students: Self, social, and academic explorations. Centre for Talented Youth Ireland and Center for Gifted Education at College of William and Mary. Available online: https://www.dcu.ie/ctyi/irish-gifted-students-self-social-and-academic-explorations (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Cross, J. R., Cross, T. L., O’Reilly, C., & Vaughn, C. T. (2019). Gifted education in Ireland: Parents’ beliefs and experiences. Centre for Talented Youth Ireland and Center for Gifted Education at College of William and Mary. Available online: https://www.dcu.ie/sites/default/files/ctyi/summary_report.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Cross, J. R., O’Reilly, C., Kim, M., Mammadov, S., & Cross, T. L. (2015). Social coping and self-concept among young gifted students in Ireland and the United States: A cross-cultural study. High Ability Studies, 26, 39–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, T. L., Cross, J. R., & O’Reilly, C. (2018). Attitudes about gifted education among Irish educators. High Ability Studies, 29(2), 169–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dare, L., & Nowicki, E. A. (2015). Twice-exceptionality: Parents’ perspectives on 2e identification. Roeper Review, 37(4), 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DES. (2004). Education for persons with special educational needs Act. Department of Education and Science. Available online: http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/1998/act/51/enacted/en/print.html (accessed on 11 October 2025).

- Desvaux, T., Danna, J., Velay, J.-L., & Frey, A. (2023). From gifted to high potential and twice exceptional: A state-of-the-art meta-review. Applied Neuropsychology: Child, 13(2), 165–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunne, O., O’Reilly, C., & O’Hara, J. (2025). Positive discoveries: Identity development and the experiences of gifted LGBTQ+ students in Ireland. Gifted and Talented International, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, J. L. (2001). School, family, and community partnerships: Preparing educators and improving schools. Westview Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, B., & Harford, J. (2023). The DEIS programme as a policy aimed at combating educational disadvantage: Fit for purpose? Irish Educational Studies, 42(3), 381–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foley-Nicpon, M., Allmon, A., Sieck, B., & Stinson, R. D. (2011). Empirical investigation of twice-exceptionality: Where have we been and where are we going? Gifted Child Quarterly, 55(1), 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martínez, I., Gutiérrez Cáceres, R., Luque de la Rosa, A., & León, S. P. (2021). Analysing educational interventions with gifted students. Systematic review. Children, 8(5), 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelbar, N. W., Renzulli, S., Theis, L. D., & Ehrenberg, A. (2022). A systematic review of the research on gifted individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Gifted Child Quarterly, 66(1), 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gierczyk, M., & Hornby, G. (2021). Twice-exceptional students: Review of implications for special and inclusive education. Education Sciences, 11(2), 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilbault, K. M., Eckert, G., & Szymanski, A. (2024). Caregiver perceptions of the social and emotional characteristics of gifted children from early childhood through the primary school years. Roeper Review, 46(4), 265–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilbault, K. M., & McCormick, K. M. (2023). The underachievement of gifted learners in school. In K. H. Collins, J. J. Roberson, & F. Piske (Eds.), Underachievement in gifted education: Perspectives, practices, and possibilities (pp. 25–41). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzić, O., & Bećirović, S. (2021). Gifted and twice-exceptional students: Definition, characteristics, and identification. Croatian Journal of Education, 23(1), 69–94. [Google Scholar]

- Hinch, L., Cross, J. R., Cross, T. L., O’Reilly, C., & Bilgic-Erdem, S. (2024). Irish teacher practice of differentiation for gifted students. Gifted Education International, 40(2), 233–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollingworth, L. S. (1923). Special talents and defects: Their significance for education. The Macmillan Company. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny, N., McCoy, S., & Mihut, G. (2020). Special education reforms in Ireland: Changing systems, changing schools. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A., Khan, S., Siraji, M. J., Akhter, S., Razaq Khan, S., & Riaz, M. (2025). A qualitative study of parents’ perspectives and advocacy for twice-exceptional children. Journal of Advanced Developmental Studies, 14(2), 88–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, E. W. (2005). Addressing the needs of gifted students with learning disabilities. Teaching Exceptional Children, 38(1), 60–64. [Google Scholar]

- Laffan, D. A., Slonje, R., Ledwith, C., O’Reilly, C., & Foody, M. (2024). Scoping bullying and cyberbullying victimisation among a sample of gifted adolescents in Ireland. International Journal of Bullying Prevention, 6(1), 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeBeau, B., Assouline, S. G., Foley-Nicpon, M., Lupkowski-Shoplik, A., & Schabilion, K. (2025). Likelihood of whole-grade or subject acceleration for twice-exceptional students. Gifted Child Quarterly, 69(3), 237–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madaus, J., Tarconish, E. J., Langdon, S., Taconet, A., & Gelbar, N. W. (2022). Parents’ perceptions of the college experiences of twice-exceptional students with autism spectrum disorder. Developmental Disabilities Network Journal, 2(2), 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, M. S., Ritchotte, J. A., & Jolly, J. L. (2014). What’s wrong with giftedness? Parents’ perceptions of the gifted label. International Studies in Sociology of Education, 24(4), 372–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]