Intervention Programmes on Socio-Emotional Competencies in Pre-Service Teachers: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

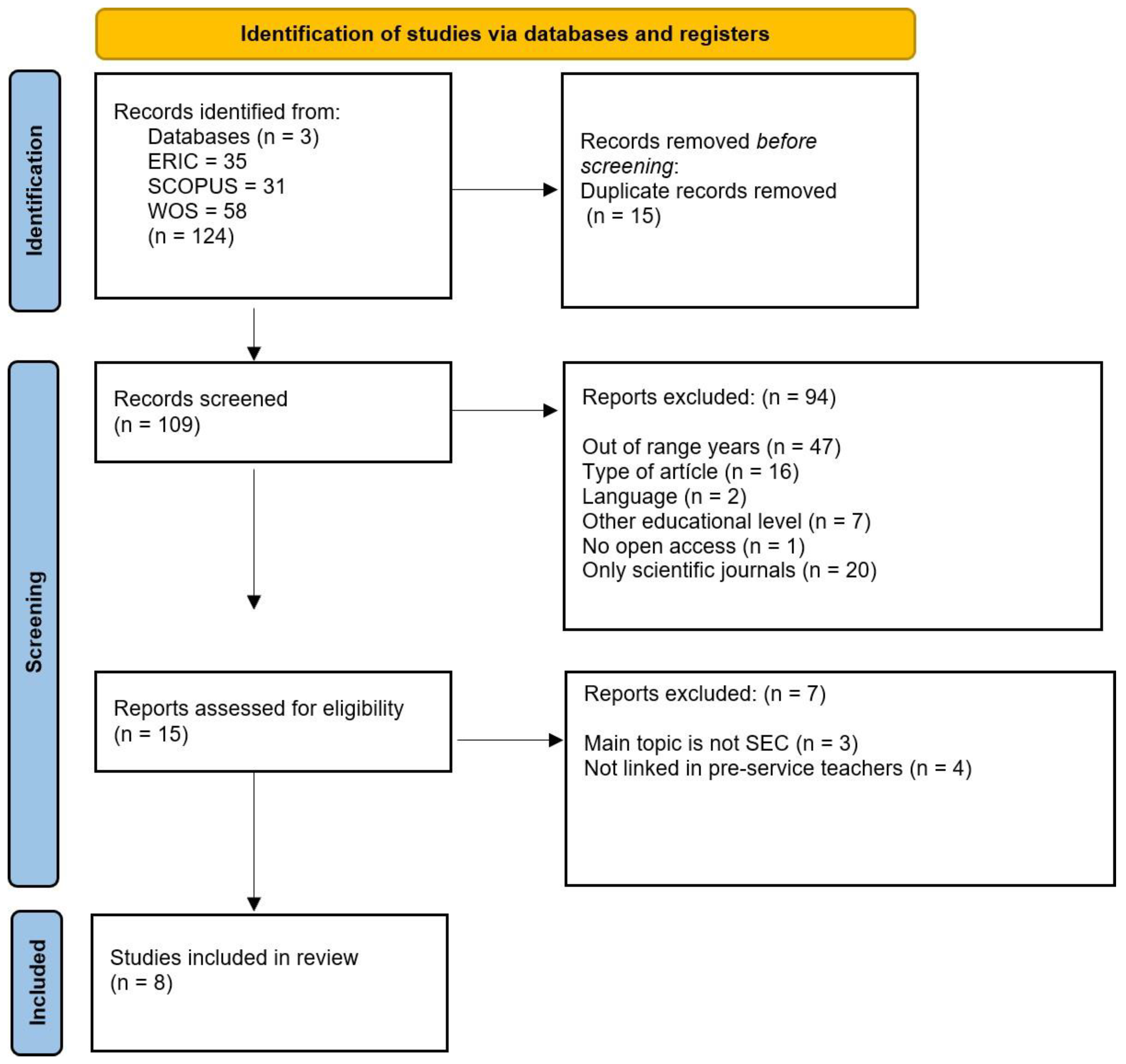

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Criteria of Eligibility

- (a)

- Publication between 2019 and 2024.

- (b)

- Journal articles.

- (c)

- Research performed in the field of university education.

- (d)

- Studied carried out in Education.

2.2. The Exclusion Criteria Were as Follows

- (a)

- Studies not published in English or Spanish.

- (b)

- Studies not published in peer-reviewed journals (conference proceedings, books, book chapters, and other types of publication).

- (c)

- Theoretical studies or reviews.

- (d)

- Master’s and doctoral studies.

- (e)

- Studies not linked to programmes for the development of socio-emotional competences in pre-service teachers.

- (f)

- Studies relating to other areas of knowledge.

2.3. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.4. Studies Selection Process

- (a)

- Articles reporting empirical studies demonstrating the effects of the relationship between assessment tools and teacher competency development within the context of initial teacher education.

- (b)

- Articles presenting experiments involving the use of one or more assessment tools and their effects.

2.5. Procedure for Data Extraction

2.6. List of Data

- (a)

- Bibliometric data (year of publication and country of origin);

- (b)

- Methodological approach and type of design (pre-experimental, quasi-experimental, phenomenological, mixed methods, etc.);

- (c)

- Assessment procedures employed (strategies and tools used); socio-emotional competencies assessed.

- (d)

- Socio-emotional competencies assessed.

- (e)

- Effects of the assessment procedures on the development of socio-emotional competencies.

3. Results

4. Discussion

Strategies Employed in the Programmes

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

5.1. Strategies Most Effective for Developing SEC Teacher Education

5.2. Limitations of Programmes

5.3. Recommendations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aspelin, J. (2019). Enhancing pre-service teachers’ socio-emotional competence. The International Journal of Emotional Education, 11(1), 153–168. [Google Scholar]

- Aspelin, J., & Jönsson, A. (2019). Relational competence in teacher education. Concept analysis and report from a pilot study. Teacher Development, 23(2), 264–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisquerra, R., & Pérez, N. (2007). Las competencias emocionales. Educación XX1, 10, 61–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caires, S., Alves, R., Martins, Ä., Magalhães, P., & Valente, S. (2023). Promoting socio-emotional skills in initial teacher training: An emotional educational programme. The International Journal of Emotional Education, 15(1), 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderón, A. (2024). Desarrollo de habilidades socioemocionales en la formación de educadores en la sociedad actual. Sophia, Colección de Filosofía de la Educación, 37, 283–309. Available online: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3378-8565.

- CASEL Guide. (2015). Effective social and emotional learning programs. Middle and High School Edition. [Google Scholar]

- Chacón-Cuberos, R., Olmedo-Moreno E, M., Lara-Sánchez, A. J., Zurita-Ortega, F., & Castro-Sánchez, M. (2021). Basic psychological needs, emotional regulation and academic stress in university students: A structural model according to branch of knowledge. Studies in Higher Education, 46, 1421–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, C. M., Przeworski, A., Smith, A. C., Obeid, R., & Short, E. J. (2023). Perceptions of social–emotional learning among K-12 teachers in the USA during the COVID-19 pandemic. School Mental Health, 15(3), 484–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, R. P., & O’Flaherty, J. (2022). Social and emotional learning in teacher preparation: Pre-service teacher well-being. Teaching and Teacher Education, 110, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devis-Rozental, C., & Farquharson, L. (2020). What influences students in their development of socio-emotional intelligence whilst at university? Higher Education Pedagogies, 5(1), 294–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElSayary, A., & Mohebi, L. (2025). Fostering preservice teachers socio-emotional, technological, and metacognitive knowledge (STM-K) using e-porfolios. Education and Information Technologies 30, 2095–2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martínez, I., Pérez-Navío, E., Pérez-Ferra, M., & Quijano-López, R. (2021). Relationship between emotional intelligence, Educational achievement and academic stress of pre-servic teachers. Behavioral Sciences, 11(7), 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, G. (1988). Learning by doing: A guide to teaching and learning methods. Oxford Brookes University Further Education Unit. [Google Scholar]

- Gkintoni, E., Vassilopoulos, S. P., & Nikolaou, G. (2025). Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy in clinical practice: A systematic review of neurocognitive outcomes and applications for mental health and well-being. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(5), 1703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy, F., & Trujillo, D. (2024). Formación en competencias socioemocionales para docentes: Una revisión sistemática. Revista Científica Internacional, 11(2), 1793–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Barco, M. A., Corbacho-Cuello, I., Sánchez-Martín, J., & Cañada-Cañada, F. (2024). A longitudinal study during scientific teacher training: The association between affective and cognitive dimensions. Frontiers in Education, 9, 1355359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta, R., & Vicario, M. (2021). Como as competências socioafetivas dos alunos do ensino superior foram abordadas na pandemia? Texto Livre. Belo Horizonte-MG, 14(2), e33937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jönsson, A., Aspelin, J., Lindberg, S., & Östlund, D. (2024). Supporting the development and improvement of teachers’ relational competency. Frontiers in Education, 9, 1290462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasperski, R., & Crispel, O. (2022). Preservice teachers’ perspectives on the contribution of simulation-based learning to the development of communication skills. Journal of Education for Teaching, 48(5), 521–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapidot-Lefler, N. (2022). Promoting the use of social-emotional learning in online teacher education. International Journal of Emotional Education, 14(2), 19–35. Available online: https://www.um.edu.mt/library/oar/handle/123456789/104134 (accessed on 14 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Peña, G., Sáez-Delgado, F., López-Angulo, Y., & Mella-Norambuena, J. (2021). Teachers’ social–emotional competence: History, concept, models, instruments, and recommendations for educational quality. Sustainability, 13, 12142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lozano-Peña, G., Sáez-Delgado, F., López-Angulo, Y., Mella-Norambuena, J., Contreras-Saavedra, C., & Ramos-Huenteo, V. (2023). Programas de intervención docente en competencias socioemocionales: Una revisión sistemática de la literatura. Aula de Encuentro, 25(2), 218–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Goñi, I., & Goñi, J. M. (2012). La competencia emocional en los currículos de formación inicial de los docentes. Un estudio comparativo. Revista de Educación, 357, 467–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, H., & Li, W. (2025). Impact of micro-learning on the development of soft skills of university students across all disciplines. Frontiers in Psychology, Sección Psicología Educativa, 16, 1491265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, J. D., & Salovey, P. (1997). What is emotional intelligence? In P. Salovey, & D. Sluyter (Eds.), Emotional development and emotional Intelligence: Implications for educators (pp. 3–31). Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Mosqueda, V. (2021). Método SCAMPER: Cómo se aplica, verbos y ejemplos. Available online: https://www.lifeder.com/metodo-scamper/ (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Muñoz, D. (2023). Las CSE de los docentes y su rol en el aula. Revista Estudios Psicológicos, 3(4), 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OCDE. (2024). Habilidades sociales y emocionales para una vida mejor: Resultados de la Encuesta de la OCDE sobre habilidades sociales y emocionales 2023. Publicaciones de OCDE. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palomera, R., Briones, E., & Gómez-Linares, A. (2019). Formación en valores y competencias socio-emocionales para docentes tras una década de innovación. Praxis & Saber, 10(24), 93–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Escoda, N., Berlanga, V., & Alegre, A. (2019). Desarrollo de competencias socioemocionales en educación superior: Evaluación del posgrado en educación emocional. Bordón. Revista De Pedagogía, 71(1), 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puertas, P., Ubago, J. L., Moreno, R., Padial, R., Martínez, A., & González, G. (2018). La inteligencia emocional en la formación y desempeño docente: Una revisión sistemática. REOP–Revista Española de Orientación y Psicopedagogía, 29(2), 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rendón, M. A. (2019). Competencias socioemocionales de maestros en formación y egresados de programas de educación. Praxis & Saber, 10(24), 243–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, S., Etchart-Puza, J., Cardenas-Zedano, W., & Herencia-Escalante, V. (2023). Competencias socioemocionales en la educación Superior. Universidad, Ciencia y Tecnología, 27(119), 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheff, T. J. (1990). Microsociology. Discourse, emotion and social structure. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schoeps, K., Postigo-Zegarra, S., Mónaco, S., González, R., & Montoya-Castilla, I. (2020). Valoración del programa de educación emocional para docentes (MADEMO). Know and Share Psychology, 1(4), 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shriver, T. P., & Weissberg, R. P. (2020). A response to constructive criticism of social and emotional learning. Phi Delta Kappan, 101(7), 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero-Moya, A. (2023). La dimensión socioemocional del profesorado: Conceptualización adaptada a la función docente. Crónica: Revista Científico Profesional de la Pedagogía y Psicopedagogía, 8, 101–114. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, F., Zeng, L. M., & King, R. B. (2024). University students’ socio-emotional skills: The role of the teaching and learning environment. Studies in Higher Education, 50(8), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S., Zhu, X., Tian, G., & Kang, X. (2023). Exploring the relationships between pre-service preparation and student teachers’ 704 social-emotional competence in teacher education: Evidence from China. Sustainability, 15(3), 2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zych, I., Marín-López, I., Fernández-Rabanillo, J. L., & García Fernández, C. M. (2022). Docentes emocional y socialmente competentes: Innovaciones para el fomento de las competencias sociales y emocionales en el alumnado de Ciencias de la Educación. Contextos Educativos. Revista de Educación, (29), 189–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number | Authors | Programmes | Country | Participants | Design |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Aspelin and Jönsson (2019) | Relational Competence | Sweden | 6 | Qualitative |

| 2 | Schoeps et al. (2020) | Emotional Education | Spain | 135 | Mixed |

| 3 | Huerta and Vicario (2021) | Online pilot programmes | México | 32 | Pre-experimental with post-test |

| 4 | ElSayary and Mohebi (2025) | Socio-Emotional, Technological, and Metacognitive Knowledge (STM-K) | United Arab Emirates | 112 | Mixed |

| 5 | Kasperski and Crispel (2022) | Simulation-based learning to the development of communication skills | Israel | 40 | Mixed |

| 6 | Zych et al. (2022) | Innovation project to promote social and emotional skills | Spain | 322 | Quasi-experimental |

| 7 | Caires et al. (2023) | Social and Emotional Learning (SEL) | Portugal | 87 | Phenomenological |

| 8 | Jönsson et al. (2024) | Relational Competence | Sweden | 9 | Mixed |

| Author | SEC | Theoretical Model | Methodology | Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aspelin and Jönsson (2019) | Relational competence: communicative, socio-emotional, and differentiation | Interpersonal Relationships Theory (Scheff, 1990) | Videos and texts | Semester |

| Schoeps et al. (2020) | Emotional perception, expression, emotional understanding, and empathy | Emotional Intelligence Model (Mayer & Salovey, 1997) | Individual and group reflection | Course |

| Huerta and Vicario (2021) | Self-awareness, self-regulation, interpersonal relations, decision-making, and leadership | Emotional Intelligence Model (Mayer & Salovey, 1997) | SCAMPER, online socializing | Course |

| ElSayary and Mohebi (2025) | Emotional awareness, communication, and collaboration | Reflection Model (Gibbs, 1988) | Reflection, TIC, portfolio | Semester |

| Kasperski and Crispel (2022) | Empathy, emotional control, assertiveness, and collaboration | Simulation-based learning (SBL) | Simulation actors, videos | Course |

| Zych et al. (2022) | Empathy, understanding, and emotional regulation | Active and interactive | Role-playing, cooperatives work | Semester |

| Caires et al. (2023) | Self-awareness, self-regulation, social awareness, relationship skills, and decision-making | Social–emotional learning (SEL) model (Shriver & Weissberg, 2020). | CASEL, emotional portfolio | Semester |

| Jönsson et al. (2024) | Relational competence: communicative, socio-emotional, and differentiation | Interpersonal Relationships Theory (Scheff, 1990); social bond | Simulation, videos, and avatars | Course |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Monroy Correa, G.M.; Manzanal Martínez, A.I. Intervention Programmes on Socio-Emotional Competencies in Pre-Service Teachers: A Systematic Review. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1588. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121588

Monroy Correa GM, Manzanal Martínez AI. Intervention Programmes on Socio-Emotional Competencies in Pre-Service Teachers: A Systematic Review. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(12):1588. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121588

Chicago/Turabian StyleMonroy Correa, Graciela Martina, and Ana Isabel Manzanal Martínez. 2025. "Intervention Programmes on Socio-Emotional Competencies in Pre-Service Teachers: A Systematic Review" Education Sciences 15, no. 12: 1588. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121588

APA StyleMonroy Correa, G. M., & Manzanal Martínez, A. I. (2025). Intervention Programmes on Socio-Emotional Competencies in Pre-Service Teachers: A Systematic Review. Education Sciences, 15(12), 1588. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15121588