1. Introduction

Research and practitioners across the globe have devoted substantial attention to the study of entrepreneurial intention. The first studies on entrepreneurial intention began more than 40 years ago (

Shapero & Sokol, 1982). Standardization of concepts and methodologies has facilitated research by enabling the generation of new knowledge and reducing problems (such as difficulties in identifying literature gaps and critical issues) (

Krueger et al., 2000;

Fayolle & Liñán, 2014). Various theoretical frameworks have been proposed to develop a model that will better explain intention, including Bandura’s self-efficacy theory (

Bandura, 1997), Ajzen’s theory of planned behavior (

Ajzen, 1991), Bird’s model of entrepreneurial intentions (

Bird, 1988), the model of intention in entrepreneurial situations (

Shapero & Sokol, 1982) and the approach that combines this model with the theory of planned behavior (

Reitan, 1996). In the present study, Ajzen’s theory of planned behavior is used to interpret the factors that affect entrepreneurial intention.

Research investigating the intersection of gender and entrepreneurship has attracted considerable scholarly attention, particularly in relation to how gender influences entrepreneurial intentions and the effectiveness of entrepreneurship education. Students of different genders approach entrepreneurship differently, mainly due to social and psychological factors that influence their attitudes and choices. Empirical evidence reveals that gender inequalities exist in entrepreneurship in a wide range of areas, including access to resources, lack of network or management experience, social expectations, and cultural stereotypes (

Neergaard et al., 2005).

Contemporary research has increasingly recognized that addressing gender disparities in entrepreneurship is not merely a matter of social justice but a critical driver of economic growth and innovation. Women entrepreneurs contribute significantly to job creation, economic development, and diversification of markets, yet they remain underrepresented in entrepreneurial activities worldwide. The mechanisms by which educational interventions can close this gender gap are being investigated by academics and policymakers in order to foster more inclusive entrepreneurial ecosystems.

The primary objective of this research is to investigate how female students react to entrepreneurial intention taking into consideration entrepreneurship education and the theory of planned behavior (TPB) factors. Given the lack of research on how female students respond to entrepreneurship education and how it influences their entrepreneurial intention through changes in attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control (

Neergaard et al., 2005;

Tsaknis et al., 2024;

Molino et al., 2018), this study offers an innovative methodological approach to examining whether changes in entrepreneurial intention among female students are associated with changes in these factors. Furthermore, by integrating sustainability principles within entrepreneurship education, this research addresses the dual challenge of promoting gender equity while advancing sustainable development goals, reflecting the contemporary understanding that entrepreneurship education must encompass both economic viability and social responsibility.

2. Theoretical Background

Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) serves as a foundational framework for understanding individual intentions (such as entrepreneurial intention), decision-making processes, and predicting behaviors. According to

Ajzen (

1991), an understanding of individual intentions is influenced by three factors: attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control. The theory of planned behavior does not work in isolation. External factors, such as gender, can significantly and differently influence entrepreneurial intentions. Research by

Yukongdi and Lopa (

2017) demonstrates that men often express more positive attitudes towards entrepreneurship than women, linking these results to the need for independence, success, and financial reward. Studies also indicate that women are more influenced by the support of role models in their social environment, but this factor does not seem to significantly affect their entrepreneurial intentions (

Molino et al., 2018;

Maes et al., 2014). Entrepreneurship is often perceived by the social environment as a male activity (

Maes et al., 2014). Regarding perceived behavioral control, studies report that women tend to have lower levels than men, reporting more barriers and less confidence in their entrepreneurial abilities (

Molino et al., 2018;

Haus et al., 2013).

2.1. The Theory of Planned Behavior in Entrepreneurship Context

The most reliable framework in understanding the formation of entrepreneurial intentions is the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB). Based on Ajzen’s original conception, intentions are the immediate antecedents of actual behavior, which are shaped by three core constructs. The attitude towards behavior reflects a person’s positive or negative assessment of performing a particular action, in this case, starting a business. Secondly, subjective norms reflect perceived social pressure from significant others regarding a particular behavior. Third, perceived behavioral control reflects an individual’s perception of the ease of executing a particular behavior (

Tsaknis & Sahinidis, 2020;

Tsaknis & Sahinidis, 2024). It has been shown that TPB is highly predictive within the domain of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurial intentions are strong predictors of subsequent entrepreneurial behaviors, with attitudes and perceived behavioral control having a greater impact on intentions than subjective norms. Different populations and cultural contexts may have different relative importance for these predictors, so it is necessary to examine them specifically for each population, especially when analyzing gender differences (

Tsaknis et al., 2024).

When applied to entrepreneurship education, TPB may provide valuable insights into how structured learning experiences can modify the psychological antecedents of entrepreneurial behavior. As part of education, students receive information about entrepreneurial opportunities and challenges, develop skills and experience to enhance perceived behavioral control, as well as influence subjective norms by creating supportive peer networks and exposing them to entrepreneurs.

2.2. Gender Dimensions in Entrepreneurial Intention

Studies indicate that women have lower entrepreneurial intentions than men. This difference can be explained by several factors (such as lack of resources, fear of failure, social influences, support, and work–life balance) (

Steinmetz et al., 2021). Nevertheless, while studies indicate a difference in entrepreneurial intention between men and women, it is emphasized that this difference is small and does not justify the large gap observed in actual entrepreneurial activity. It is argued that other systemic and social factors are considered more decisive for understanding this phenomenon (

Steinmetz et al., 2021). Entrepreneurship in many cases is associated with male stereotypes, with leadership, willingness to take risks, and extraversion.

Eagly and Karau (

2002) (Role Congruity Theory) argue that social expectations for gender roles have an impact on the perception and acceptance of a professional choice. When the characteristics of a social role (e.g., entrepreneur) clash with gender stereotypes, then the gender that chooses to follow such a path may experience social pressure, rejection, or internal conflict, respectively (

Eagly & Karau, 2002). Women often develop a greater fear of failure compared to men, which acts as a deterrent to undertaking entrepreneurial initiatives (

Langowitz & Minniti, 2007;

Wagner & Sternberg, 2004). This fear is often reinforced by social expectations, lack of support networks, and reduced access to financial resources. Women’s reduced access to finance compared to men is not due to a lack of ability or innovation, but to deep-rooted biases in the investment environment (

Brush et al., 2018).

There are multiple psychological, social, and structural factors that interact and create the gender gap in entrepreneurship. This phenomenon cannot be attributed to one cause alone. In recent research, scholars revealed how implicit gender biases shape career aspirations and hinder women’s access to resources and opportunities (

Swartz & Amatucci, 2018;

Guzman & Kacperczyk, 2019), as early socialization processes shape career aspirations and institutional barriers constrain women’s opportunities (

Panda, 2018).

The social cognitive approach provides additional insight into the development and persistence of gender differences in entrepreneurial intentions (

Liguori et al., 2018). Gender stereotypes about entrepreneurship as a masculine domain influence how individuals perceive entrepreneurs and their own entrepreneurial potential (

Gupta et al., 2009) and can lead women to doubt their entrepreneurial capabilities and self-select out of entrepreneurial careers. Children develop cognitive schemas that organize information about gender roles (

Bem, 1981). Gender-typed behaviors are learned through observing and modeling others (

Bussey & Bandura, 1999). As a result of these internalized beliefs, women may be influenced in their career decisions and self-perceptions as entrepreneurs.

Work–life balance constitutes an important factor determining the difference in entrepreneurial intentions between men and women. Family obligations often demand a lot of women’s time and energy, limiting their time and energy for entrepreneurship (

Jennings & Brush, 2013). Men are often less affected by family responsibilities and usually have more support from their environment to be able to devote their time to professional ambitions. The lack of measures that facilitate the balance of work and family life increases inequalities (flexible working hours, maternity leave, etc.). Without supportive policies and social infrastructures, women are much more likely to abandon entrepreneurial endeavors (

OECD & European Commission, 2023). However, it is argued that many women choose to follow an entrepreneurial path because they seek more flexibility and control over their time.

2.3. Entrepreneurship Education as a Transformative Tool

Research demonstrates that entrepreneurship education strengthens students’ attitudes towards entrepreneurship, strengthens the perception that they have the necessary abilities and skills to succeed in business (perceived behavioral control), increases the levels of subjective norms (a new circle of students with common interests, especially in entrepreneurship, is created) and promotes entrepreneurial intentions (

Tsaknis & Sahinidis, 2025;

Kautonen et al., 2015). The international literature revealed that research on how education can differentially affect different groups of students (especially male vs. female students) has not been sufficiently explored (

Haus et al., 2013;

Tsaknis et al., 2024). Additionally, it is of particular interest to determine how entrepreneurship education affects female students’ entrepreneurial intentions, the factors examined (attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, entrepreneurial intention) and the relationships between those factors.

Entrepreneurship education has evolved significantly over the past decade. Students participate in real-world entrepreneurial activities such as ideation workshops, business simulations, pitch competitions, etc. as part of entrepreneurship education. In these terms, it is understood that entrepreneurship is not just about transmitting knowledge but is also about developing entrepreneurial mindsets and behaviors (

Tsaknis & Sahinidis, 2025;

Tsaknis et al., 2025).

Studies suggest that entrepreneurship education may benefit women differently than it does men, with educational interventions potentially enhancing women’s entrepreneurial self-efficacy and intentions more than men’s (

Wilson et al., 2007). This is due to entrepreneurship education providing women with experiences and knowledge, mentorship, role models, and creating supportive peer communities that validate women’s aspirations.

Research suggests that female entrepreneurs tend to prioritize social value creation more than their male counterparts (

Hechavarría et al., 2017). This orientation toward social goals aligns with broader patterns in gender roles and stereotypes, in which women are more commonly associated with communal values and caretaking behaviors (

Eagly & Wood, 2012). As entrepreneurship education integrates sustainability principles—environmental stewardship, social responsibility, and economic viability—women’s values and strengths are explicitly recognized and leveraged, and female students may find entrepreneurship more appealing and accessible if these principles are integrated.

Examining female students in conjunction with the theory of planned behavior allows us to better understand how individual differences influence entrepreneurial education effectiveness (

Maes et al., 2014;

Haus et al., 2013;

Tsaknis et al., 2024). This study contributes significantly to the field by providing insight into how changes in TPB variables (attitude, subjective norms and perceptions of behavioral control) impact entrepreneurial intentions. Through this combination, we are able to develop new perspectives on how entrepreneurship education can benefit entrepreneurial intentions among female students.

3. Methods

The empirical research that examined the effect of entrepreneurship education on female students’ entrepreneurial intentions based on the theory of planned behavior is limited. The purpose of the study was achieved by using pre-experimental and post-experimental questionnaires among students enrolled in a semester-long entrepreneurship course. As part of the course, sustainability principles were incorporated throughout, emphasizing the triple bottom line approach (economic viability, environmental stewardship, and social responsibility). The concept of sustainability served as both a pedagogical orientation and a learning outcome. Students examined sustainable ventures, including several led by women entrepreneurs, and developed business plans incorporating sustainability dimensions. At the beginning of the course, 320 students completed the first questionnaire. Thirteen weeks later, at the end of the semester, 271 students who had filled out the first questionnaire completed the second, yielding an 84.7% response rate. Participants were fourth-year business administration students. Academic backgrounds were relatively homogeneous, all enrolled in the same program. Using chi-square analysis, we compared retention rates between male and female students to examine possible gender-related bias in attrition. Among the original participants, 88.2% of female students (157 of 178) and 80.3% of male students (114 of 142) completed both surveys. This difference was not statistically significant (χ2 = 3.23, p = 0.072), indicating that attrition did not systematically differ by gender.

In both questionnaires, students were asked to assess the factors of attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and entrepreneurial intention. Data was collected using Google Forms and analyzed using SPSS version 24. To identify the linear components and the loadings of the variables that form each component, principal component analysis with Varimax rotation was used. To determine whether the data were suitable for PCA, Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity were used. Based on the gender of the participants, the sample was divided into two groups (females and males). This study examined changes in the factors of the Theory of Planned Behavior and entrepreneurial intention among female students, as well as how changes in the factors of the theory of planned behavior affected the changes in entrepreneurial intention following a sustainability-focused entrepreneurship course. Detailed information about all measures is presented in

Table A1 and

Table A2 (

Appendix A), including scale items, factor loadings, and reliability coefficients (Cronbach’s alpha).

Statistically significant differences between females and males were determined by one-way ANOVA. In order to examine the differences in the examined factors before and after education (attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, entrepreneurial intention) in female students, a Paired-Samples t-test was used. Finally, the MEMORE macro was used to determine whether changes in the factors of the theory of planned behavior affected entrepreneurial intentions levels among female students before and after education.

This study advances methodological approaches to evaluating entrepreneurship education effectiveness by combining pre-post quasi-experiments with mediation analysis. Using the MEMORE macro for within-subject mediation helps us understand not just whether educational interventions work, but how they work—specifically, which psychological mechanisms mediate the association between education and entrepreneurial intention. Mechanistic understanding is essential for improving educational programs and targeting the psychological constructs that most influence women’s entrepreneurial intentions. In contrast to existing research on gender and entrepreneurship education that focuses primarily on whether differences exist or change, our study employs a mediation approach to reveal underlying causal mechanisms. Specifically, we examine how changes in TPB components (attitude, perceived behavioral control) lead to changes in entrepreneurial intention, expanding our knowledge of how education influences women’s entrepreneurial development beyond descriptive findings.

4. Results

The variables with the greatest loadings were assigned to each component based on Principal Component Analysis. The criteria were met according to indicators of sampling adequacy, KMO (Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy) and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity. Consistent with theoretical expectations, the questions are loaded into the relevant components. Attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control and entrepreneurial intention (before and after education) had loadings above 0.5 (

Table A1,

Appendix A). Cronbach’s Alpha reliability coefficient for all the components was above 0.7 (

Table A2,

Appendix A), demonstrating adequate internal consistency.

The sample (

n = 271) was categorized into 2 groups of students based on their gender. In the first group were categorized men (

n = 114) and in the second group, women (

n = 157). One-Way ANOVA (

Table 1) indicated statistically significant differences between the 2 groups of students for the following variables: attitude, perceived behavioral control and entrepreneurial intention before and after entrepreneurship education in sustainability. Compared to male students, female students indicated lower levels of attitude, perceived behavioral control and entrepreneurial intention both before and after education. However, subjective norms before and after education did not indicate statistically significant differences between the groups, suggesting that social pressures regarding entrepreneurship are perceived similarly across genders.

The results presented in

Table 2 display the

t-test outcomes for the examined pairs of samples (attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, entrepreneurial intention before and after entrepreneurship teaching) for each group of students.

Table 2 summarizes the statistics for each of the experimental conditions (mean, standard deviation, standard error) for the two groups of students. In the first group (male students) there was a statistically significant and positive change only in perceived behavioral control. In the second group of students (female students), attitude, perceived behavioral control and entrepreneurial intention were positively affected by entrepreneurship education.

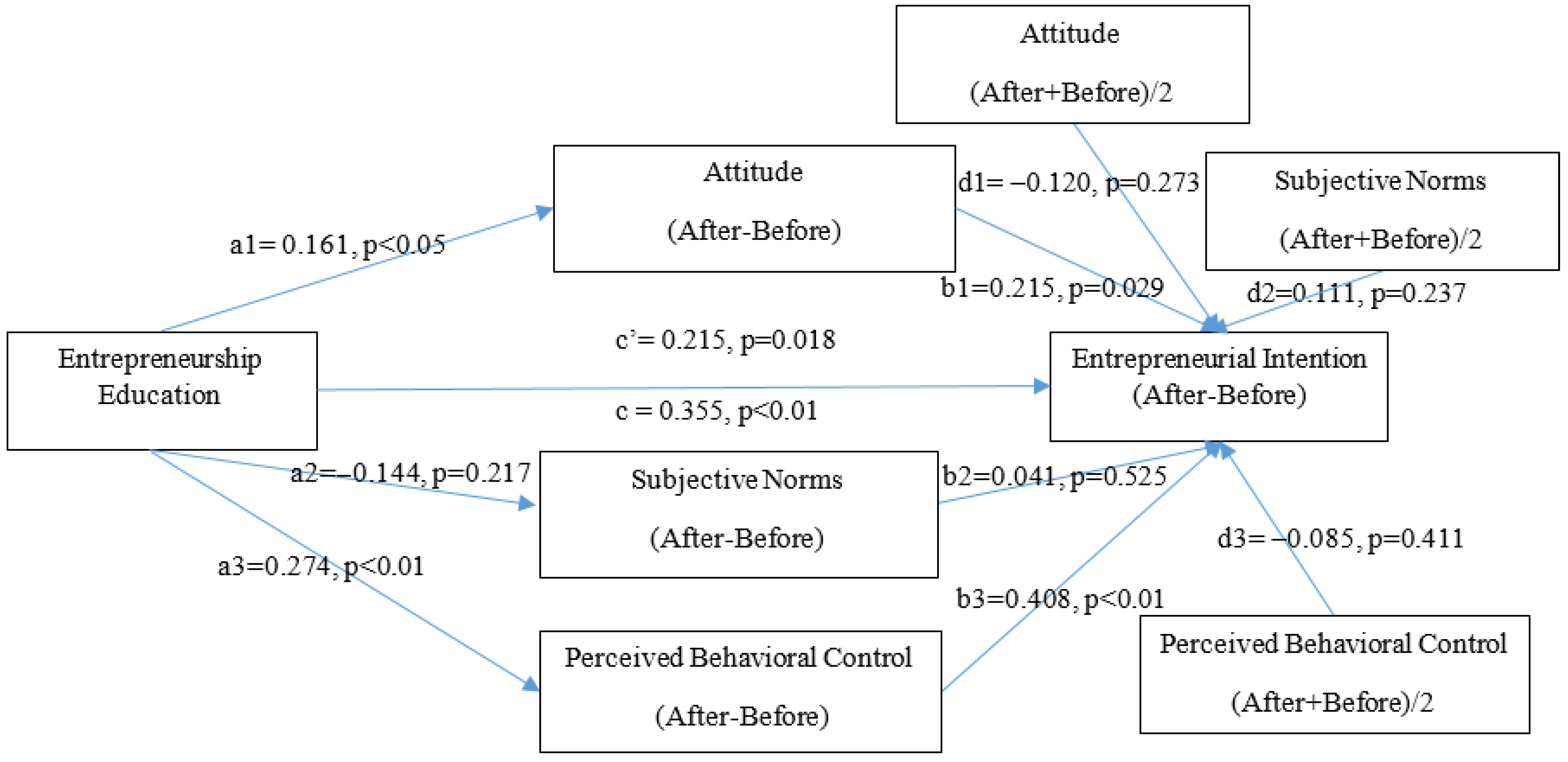

T-test results indicated that there is a positive change in entrepreneurial intention after entrepreneurship education, only in female students. MEMORE macro (

Figure 1) was applied to female students in order to clarify whether the change in entrepreneurial intention was influenced by changes in attitude or perceived behavioral control (which existed in this group of students).

According to the above model (MEMORE macro), entrepreneurship education indicated a statistically significant positive total effect on entrepreneurial intention (c = 0.355, p < 0.01) and direct effect (c’ = 0.215, p = 0.018). MEMORE macro indicated that the positive change in attitude and perceived behavioral control affected the positive change in entrepreneurial intention after entrepreneurship education in sustainability (b1 = 0.215, p = 0.029) and (b3 = 0.408, p < 0.01) respectively.

5. Discussion

Our findings provide compelling evidence regarding the effects of entrepreneurship education in sustainability on female students and more specifically determine whether changes in entrepreneurial intentions were driven by the changes of the factors of the Theory of Planned Behavior. Adapting entrepreneurship education to gender factors can have both theoretical and practical implications. From a theoretical standpoint, it offers new evidence regarding the role of gender in entrepreneurial intentions and the factors of the theory of planned behavior. From a practical perspective, the findings have implications for education, policy-making, and human resource management in the entrepreneurship field. In light of these findings, more effective entrepreneurship programs can be developed, which are tailored to the needs and profiles of participants, thereby increasing the likelihood that they will develop higher levels of entrepreneurial intentions after education (

Tsaknis & Sahinidis, 2025;

Tsaknis et al., 2024).

These findings resonate strongly with prior studies that emphasize the transformative power of entrepreneurship education in shaping entrepreneurial intentions, especially among women (

Molino et al., 2018;

Haus et al., 2013;

Tsaknis et al., 2024). Previous literature highlights how gender-specific barriers—such as lower self-efficacy, limited access to resources, and socially imposed role expectations—negatively impact women’s entrepreneurial engagement (

Steinmetz et al., 2021;

Eagly & Karau, 2002;

Brush et al., 2018). Our results support these conclusions, as female students initially reported significantly lower levels of attitude, perceived behavioral control, and entrepreneurial intention compared to male students. However, consistent with the findings of

Tsaknis and Sahinidis (

2025) and

Haus et al. (

2013), the entrepreneurship course had a positive influence, particularly by increasing perceived behavioral control, which in turn enhanced entrepreneurial intention. This reinforces the argument that tailored educational interventions can mitigate gender disparities in entrepreneurial behavior and promote more inclusive and sustainable economic development (

Tsaknis et al., 2024).

Women’s perceived behavioral control and attitude play a critical role in determining entrepreneurial intention based on educational exposure (

Wilson et al., 2007;

Tsaknis et al., 2024). Female students need more confidence-building and skill development than men. It may be particularly crucial for women to emphasize perceived control and attitude owing to additional obstacles-both perceived and real-to entrepreneurship. The development of educational programs that enhance women’s beliefs in their entrepreneurial capabilities and attitudes can help them overcome some of the psychological obstacles created by gender stereotypes and social conditioning.

Sustainability integration is an important component of entrepreneurship education. It is possible that the positive outcomes for women students are partly attributable to the values-based approach that is inherent in sustainability-oriented curricula. As entrepreneurship education incorporates social and environmental concerns, we create a framework that resonates with many women’s values and interests, potentially making it more appealing and accessible for them. As a result, curriculum design has an important role to play in creating inclusive and welcoming learning environments for a diverse population of students.

Our findings contribute to the ongoing debate concerning gender differences in entrepreneurship by suggesting that appropriate education interventions can reduce differences in entrepreneurial intention by a significant amount. At the beginning of the course, women had significantly lower entrepreneurial attitudes, perceived behavioral control, and intentions than men. As a result, the malleability of entrepreneurial intentions challenges deterministic perspectives that view gender intervention differences as static.

By combining a pre-post experimental design with within-subject mediation analyses, this study provides a robust framework to describe how educational interventions affect entrepreneurial intentions. Therefore, curriculum designers and educators can gain actionable insights into behavioral changes that result from psychological processes.

Governments, organizations, employers, educational institutions, and policymakers can use the findings of this study to tailor entrepreneurship programs and identify individuals who will benefit the most from them. Collaboration between educational institutions and businesses through programs like business idea competitions and incubator partnerships can strengthen the connection between theory and practice. An organization’s vitality can be enhanced by entrepreneurship. Skills related to solving problems, recognizing opportunities, presenting, and understanding work functions (finance, marketing, human resources) increase employability and self-esteem. Entrepreneurship principles taught to students in entrepreneurship programs can be applied at the organizational level and by employees themselves when making decisions, promoting innovation and flexibility (

Tsaknis et al., 2025;

Tsaknis & Sahinidis, 2025). Employees can learn how to solve problems, respond to new opportunities, and think creatively.

Institutions should consider implementing gender-responsive entrepreneurship curricula that address the unique challenges women face in entrepreneurial contexts. Female students can also engage in mentorship programs that connect them with successful women entrepreneurs, as well as design learning activities that build confidence and self-efficacy. Instructors should be trained to recognize and counter implicit gender biases in classroom interactions and assessment practices as part of faculty development programs.

Policymakers should recognize the importance of entrepreneurship education for advancing gender equity and economic inclusion. Policy frameworks should support partnerships between educational institutions, industry, and entrepreneurship support organizations in order to support women entrepreneurs from education through venture launch and growth. Organizations can implement intrapreneurship programs to promote innovative thinking among different groups of employees. Incorporating the principles of entrepreneurship education into the context of organizations will allow companies to ensure gender equality in innovation roles and leadership positions.

It is imperative for business incubators and accelerators to recognize that supporting women entrepreneurs may require different elements or emphases in their programs. According to our findings, confidence-building and skill development are particularly important in enhancing perceived behavioral control, while fostering positive entrepreneurial attitudes through exposure to successful role models and reframing narratives around women’s business ownership can strengthen their belief in the value and desirability of entrepreneurship. Organizations that support women’s entrepreneurial endeavors should ensure that mentorship programs, skills training, and peer networks validate their entrepreneurial ambitions.

While this study contributes valuable insights, the effectiveness of entrepreneurship programs among female students remains an underexplored area. However, the findings are subject to certain limitations. As our study focuses on psychological factors through the Theory of Planned Behavior framework, we acknowledge that gender differences in entrepreneurial intention are influenced by multiple factors. Observed gender differences may be attributed to structural barriers, such as different access to financial capital, business networks, and mentorship opportunities, differences in prior entrepreneurial exposure, etc. Future research should examine the interplay between individual psychological factors and systemic structural inequality at multiple levels. In addition, while our course integrates sustainability principles, we did not empirically isolate its specific contribution from general entrepreneurship education. Using comparative designs, future research will clarify whether sustainability framing benefits women differently from men. There is no focus on factors such as age, previous work experience, and previous education (especially in entrepreneurship). This study is limited to a sample of Greek university students, which may constrain the generalizability of the findings. Using samples from different nationalities would be more informative and could improve results’ validity. It would be particularly useful to enhance the methodological rigor in order to improve the reliability and validity of the results. Expanding the sample size would strengthen the statistical power of the study and improve the generalizability of the results. The effectiveness of entrepreneurship education could be further assessed by implementing longitudinal surveys or mixed methodological designs (quantitative and qualitative) when collecting data (

Tsaknis et al., 2025;

Tsaknis & Sahinidis, 2025). Our study employs a pre-post design without a control group, which limits causal inferences about the educational intervention’s role. Including comparison or control groups would strengthen causal conclusions.

Several additional limitations warrant acknowledgment. First, our study captures only immediate post-course effects and cannot assess whether the observed changes in entrepreneurial intention persist over time or translate into actual entrepreneurial behavior. Longitudinal research tracking participants for several years after completing entrepreneurship education would provide valuable insights into the durability of educational impacts and the relationship between intention and action. Such research could identify factors that support or hinder the conversion of intentions into entrepreneurial activity.

Future research should also explore how to design entrepreneurship education programs that are most effective for women. A number of questions remain regarding the effectiveness of different approaches to education (experiential vs. didactic), the importance of same-gender learning environments vs. mixed-gender learning environments, the role of mentors and role models, as well as the ideal timing and duration of educational interventions. A comparative effectiveness study could help guide curriculum design that is based on evidence. It is also important to examine how entrepreneurship education interacts with contextual factors, including institutional support, cultural norms regarding gender roles, economic conditions, and the availability of resources. It is important to understand these contextual moderators to better explain why entrepreneurship education may perform better in some settings than others and adapt programs according to the context.

6. Conclusions

Theoretical advancement and practical application of entrepreneurship education can be greatly enhanced by addressing factors such as gender. By providing new insights into how gender influences entrepreneurial intentions and the underlying mechanisms of the Theory of Planned Behavior, this research enriches existing models that explain entrepreneurial development. Taking these findings into account, we can design effective entrepreneurship education, formulate effective policies, and implement effective human resource management strategies. Developing entrepreneurship programs that are tailored to the needs and profiles of participants may result in more effective outcomes, increasing the likelihood that learners will develop stronger entrepreneurial intentions after completing the program (

Tsaknis et al., 2025;

Tsaknis & Sahinidis, 2025).

This study demonstrates that gender disparities in entrepreneurial intentions are malleable outcomes that can be shaped by thoughtful educational interventions. Women students have demonstrated significant positive changes in attitudes toward entrepreneurship, confidence in their entrepreneurship abilities, and ultimately entrepreneurial intentions, providing compelling evidence that education can serve as an equalizer.

According to the centrality of perceived behavioral control as a mediating mechanism, interventions can be effective: programs that build women’s confidence in their entrepreneurial abilities can catalyze meaningful increases in entrepreneurship intentions. This is not only about transferring knowledge, but fundamentally reshaping the way women see themselves and their capabilities. As long as women believe they can navigate the challenges of entrepreneurship successfully, they are more likely to pursue entrepreneurial careers.

Incorporating sustainability principles into entrepreneurship education represents a promising approach to making entrepreneurship more accessible and appealing to women. By framing entrepreneurship not only as a vehicle for profit-seeking, but also as one that creates positive social and environmental impacts, we align entrepreneurial activity with values that resonate broadly and allow for diverse entrepreneurial identities and motivations to thrive. It has been found that values-based approaches to entrepreneurship education can be particularly helpful in attracting and retaining women and other underrepresented groups.

With an eye on the future, the need for gender-inclusive entrepreneurship education becomes increasingly obvious. It is imperative to enable more women to pursue entrepreneurship not only for fairness and equity reasons, but also for economic and social reasons. An entrepreneurial ecosystem that is diverse produces more innovation, creates more jobs, and finds solutions to a wide range of problems. Investing in entrepreneurship education for diverse groups of individuals fosters dynamic, resilient, and inclusive economies.

It is becoming increasingly clear that entrepreneurship education can make a significant contribution to social change when it is carefully designed and delivered. Through this process, stereotypes can be challenged, capabilities can be built, ambitions can be inspired, and eventually, individuals and collectives can be transformed. To realize entrepreneurship’s true potential, educators, researchers, policymakers, and practitioners need to refine entrepreneurship education approaches that emphasize equity, inclusion, and sustainability. By reducing disparities in entrepreneurial intentions, educational interventions designed specifically for gender can lead to more equitable and sustainable economic growth. Women’s entrepreneurial empowerment and future research can be fostered through education.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.A.T., A.G.S. and A.K.; methodology, P.A.T., A.G.S. and A.K.; software, P.A.T., A.G.S. and A.K.; validation, P.A.T., A.G.S. and A.K.; formal analysis, P.A.T., A.G.S. and A.K.; investigation, P.A.T., A.G.S. and A.K.; resources, P.A.T., A.G.S. and A.K.; data curation, P.A.T., A.G.S. and A.K.; writing—original draft preparation, P.A.T., A.G.S. and A.K.; writing—review and editing, P.A.T., A.G.S. and A.K.; visualization, P.A.T., A.G.S. and A.K.; supervision, A.G.S.; project administration, P.A.T., A.G.S.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The research has been funded for open access publication by the International Conference on Strategic Innovative Marketing and Tourism (ICSIMAT), University of West Attica, Greece.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study is exempt from ethical review due to its anonymous, risk-free, and educational nature, as determined by the Institutional Committee.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent for publication was obtained from all identifiable human participants.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Principal Component Analysis.

Table A1.

Principal Component Analysis.

| | Attitude | Subjective Norms | Perceived Behavioral Control | Entrepreneurial Intention |

|---|

| 1st Questionnaire Before Entrepreneurship Education |

| “Being an entrepreneur means more advantages than disadvantages” | 0.85471 | | | |

| “Entrepreneurial career is very desirable” | 0.68552 | | | |

| “If I could become an entrepreneur, that would be great satisfaction for me” | 0.57922 | | | |

| “My friends would approve my decision to start a business” | 0.88572 | | |

| “My family would approve my decision to start a business” | 0.89301 | | |

| “People who are very important to me would approve my decision to start a business” | 0.89606 | | |

| “I believe I have all the qualifications to start a business” | 0.82300 | |

| “I believe I can control the process of starting a business” | 0.81595 | |

| “If I would start a business, the chances of success would be very high” | 0.79372 | |

| “I know all the practical details needed to start a business” | 0.67455 | |

| “It is easy for me to start a successful business” | 0.79909 | |

| “Becoming an entrepreneur is my professional goal” | 0.84007 |

| “I am determined to start my own business in the (visible) future” | 0.88249 |

| “I am seriously thinking to start my own business” | 0.89210 |

| “I have the intention to start a business in the future” | 0.87720 |

| 2nd Questionnaire After Entrepreneurship Education |

| “Being an entrepreneur means more advantages than disadvantages” | 0.79744 | | | |

| “Entrepreneurial career is very desirable” | 0.69610 | | | |

| “If I could become an entrepreneur, that would be great satisfaction for me” | 0.66029 | | | |

| “My friends would approve my decision to start a business” | 0.80907 | | |

| “My family would approve my decision to start a business” | 0.83774 | | |

| “People who are very important to me would approve my decision to start a business” | 0.84622 | | |

| “I believe I have all the qualifications to start a business” | 0.82229 | |

| “I believe I can control the process of starting a business” | 0.79246 | |

| “If I would start a business, the chances of success would be very high” | 0.77798 | |

| “I know all the practical details needed to start a business” | 0.77341 | |

| “It is easy for me to start a successful business” | 0.78297 | |

| “Becoming an entrepreneur is my professional goal” | 0.72067 |

| “I am determined to start my own business in the (visible) future” | 0.84661 |

| “I am seriously thinking to start my own business” | 0.87519 |

| “I have the intention to start a business in the future” | 0.84384 |

Table A2.

Cronbach’s Alpha.

Table A2.

Cronbach’s Alpha.

| Component | Items | Cronbach’s Alpha |

|---|

| Attitude (Before) | 3 | 0.80356 |

| Subjective Norms (Before) | 3 | 0.89049 |

| Perceived Behavioral Control (Before) | 5 | 0.87609 |

| Entrepreneurial Intention (Before) | 4 | 0.95016 |

| Attitude (After) | 3 | 0.81742 |

| Subjective Norms (After) | 3 | 0.84695 |

| Perceived Behavioral Control (After) | 5 | 0.89141 |

| Entrepreneurial Intention (After) | 4 | 0.93926 |

References

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W.H. Freeman and Company. [Google Scholar]

- Bem, S. L. (1981). Gender schema theory: A cognitive account of sex typing. Psychological Review, 88(4), 354–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, B. (1988). Implementing entrepreneurial ideas: The case for intention. Academy of Management Review, 13(3), 442–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brush, C., Greene, P., Balachandra, L., & Davis, A. (2018). The gender gap in venture capital: Progress, problems, and perspectives. Venture Capital, 20(2), 115–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussey, K., & Bandura, A. (1999). Social cognitive theory of gender development and differentiation. Psychological Review, 106, 676–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A. H., & Karau, S. J. (2002). Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychological Review, 109(3), 573–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagly, A. H., & Wood, W. (2012). Biosocial construction of sex differences and similarities in behavior. In J. M. Olson, & M. P. Zanna (Eds.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 46, pp. 55–123). Academic Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayolle, A., & Liñán, F. (2014). The future of research on entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Research, 67(5), 663–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V. K., Turban, D. B., Wasti, S. A., & Sikdar, A. (2009). The role of gender stereotypes in perceptions of entrepreneurs and intentions to become an entrepreneur. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(2), 397–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, J., & Kacperczyk, A. (2019). Gender gap in entrepreneurship. Research Policy, 48(7), 1666–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haus, I., Steinmetz, H., Isidor, R., & Kabst, R. (2013). Gender effects on entrepreneurial intention: A meta-analytical structural equation model. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 5(2), 130–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hechavarría, D. M., Terjesen, S. A., Ingram, A. E., Renko, M., Justo, R., & Elam, A. (2017). Taking care of business: The impact of culture and gender on entrepreneurs’ blended value creation goals. Small Business Economics 48, 225–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, J. E., & Brush, C. G. (2013). Research on women entrepreneurs: Challenges to (and from) the broader entrepreneurship literature? The Academy of Management Annals, 7(1), 663–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kautonen, T., van Gelderen, M., & Fink, M. (2015). Robustness of the theory of planned behavior in predicting entrepreneurial intentions and actions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(3), 655–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N. F., Reilly, M. D., & Carsrud, A. L. (2000). Competing models of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing, 15(5–6), 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langowitz, N., & Minniti, M. (2007). The entrepreneurial propensity of women. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 31(3), 341–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liguori, E. W., Bendickson, J. S., & McDowell, W. C. (2018). Revisiting entrepreneurial intentions: A social cognitive career theory approach. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 14(1), 67–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maes, J., Leroy, H., & Sels, L. (2014). Gender differences in entrepreneurial intentions: A TPB multi-group analysis at factor and indicator level. European Management Journal, 32(5), 784–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molino, M., Dolce, V., Cortese, C. G., & Ghislieri, C. (2018). Personality and social support as determinants of entrepreneurial intention: Gender differences in Italy. PLoS ONE, 13(6), e0199924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neergaard, H., Shaw, E., & Carter, S. (2005). The impact of gender, social capital and networks on business ownership: A research agenda. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 11(5), 338–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD & European Commission. (2023). The missing entrepreneurs 2023: Policies for inclusive entrepreneurship and self-employment. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Panda, S. (2018). Constraints faced by women entrepreneurs in developing countries: Review and ranking. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 33(4), 315–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reitan, B. (1996, May 18–20). Entrepreneurial intentions: A combined models approach. 9th Nordic Small Business Research Conference, Lillehammer, Norway. [Google Scholar]

- Shapero, A., & Sokol, L. (1982). The social dimensions of entrepreneurship. In C. A. Kent, D. L. Sexton, & K. H. Vesper (Eds.), Encyclopedia of entrepreneurship (pp. 72–90). Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Steinmetz, H., Isidor, R., & Bauer, C. (2021). Gender differences in the intention to start a business: An updated and extended meta-analysis. Zeitschrift für Psychologie, 229(2), 70–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swartz, E., & Amatucci, F. (2018). Framing second generation gender bias: Implications for women’s entrepreneurship. Management Research Review, 41(7), 815–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaknis, P. A., & Sahinidis, A. G. (2020). An investigation of entrepreneurial intention among university students using the Theory of Planned Behavior and parents’ occupation. In A. Masouras, G. Maris, & A. Kavoura (Eds.), Entrepreneurial development and innovation in family businesses and SMEs (pp. 149–166). IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaknis, P. A., & Sahinidis, A. G. (2024). Do personality traits affect entrepreneurial intention? The mediating role of the theory of planned behavior. Development and Learning in Organizations: An International Journal, 38(6), 31–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaknis, P. A., & Sahinidis, A. G. (2025). The power of knowledge in shaping entrepreneurial intentions: Entrepreneurship education in sustainability. Sustainability, 17(15), 6785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaknis, P. A., Sahinidis, A. G., Kavoura, A., & Kiriakidis, S. (2025). The differential effects of personality traits and risk aversion on entrepreneurial intention following an entrepreneurship course. Administrative Sciences, 15(2), 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsaknis, P. A., Sahinidis, A. G., Kiriakidis, S., & Kavoura, A. (2024). Gender and entrepreneurship education effectiveness. A comparative study. In The international conference on strategic innovative marketing and tourism (pp. 657–662). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, J., & Sternberg, R. (2004). Start-up activities, individual characteristics, and the regional milieu: Lessons for entrepreneurship support policies from German micro data. The Annals of Regional Science, 38(2), 219–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, F., Kickul, J., & Marlino, D. (2007). Gender, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and entrepreneurial career intentions: Implications for entrepreneurship education. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 31(3), 387–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukongdi, V., & Lopa, N. Z. (2017). Entrepreneurial intention: A study of individual, situational and gender differences. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 24(2), 333–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).