Entrepreneurial Career: A Critical Occupational Decision

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background and Research Hypotheses

2.1. Entrepreneurial Intention

2.2. Nascent Entrepreneurial Behaviors

2.3. Physiological and Emotional States

2.4. Entrepreneurship as Career and Dysfunctional Career Beliefs

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Participants

3.2. Constructs and Measures

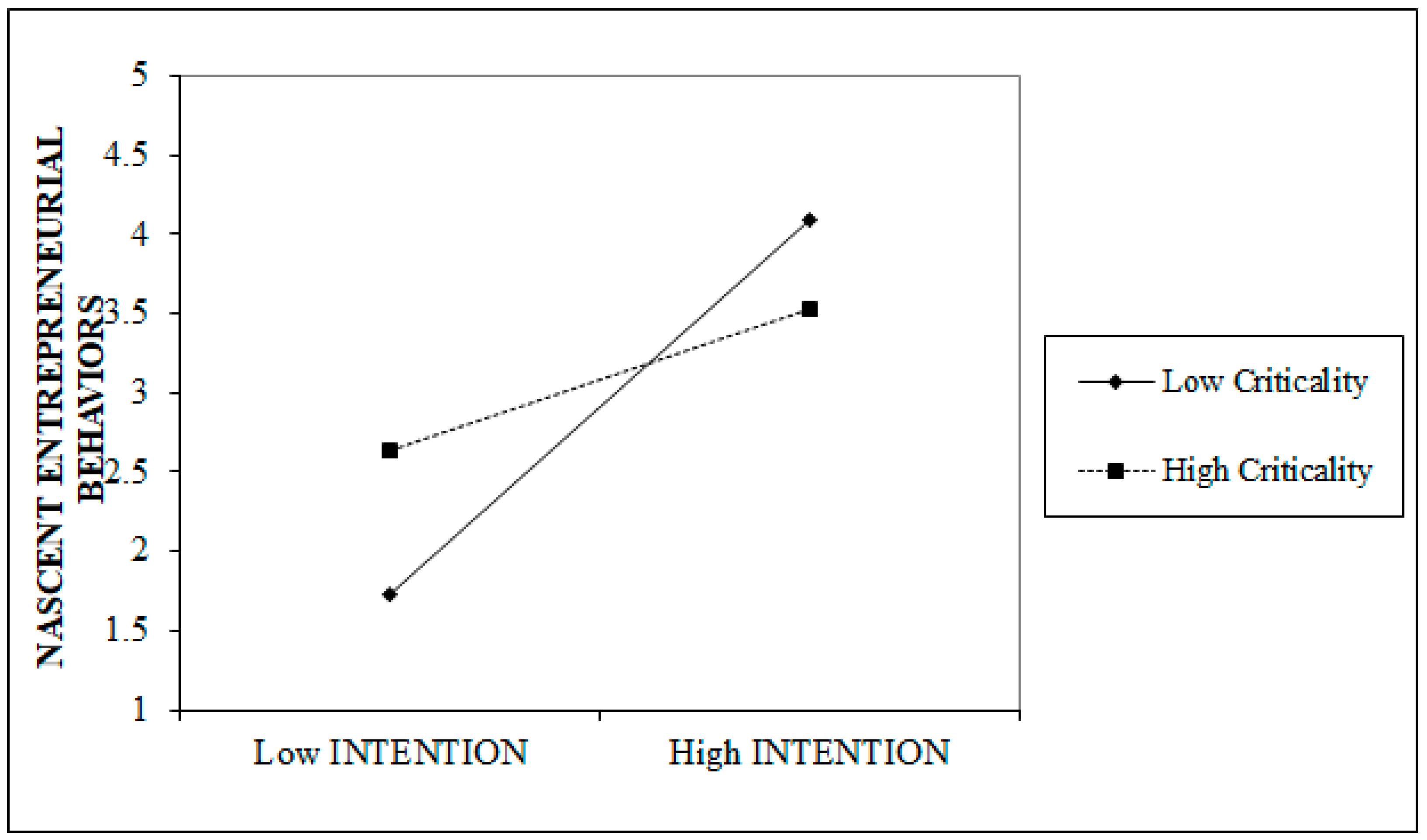

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Implications, Limitations and Further Research

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| 1 Not at All | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 To a Great Extent | ||

| Positive emotions | Determined | |||||

| Inspired | ||||||

| Energetic | ||||||

| Excited | ||||||

| Negative emotions | Upset | |||||

| Nervous | ||||||

| Afraid | ||||||

| Overstretched |

References

- Adebusuyi, A. S., Adebusuyi, O. F., & Kolade, O. (2022). Development and validation of sources of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and outcome expectations: A social cognitive career theory perspective. The International Journal of Management Education, 20(2), 100572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anghel, E., & Gati, I. (2021). The associations between career decision-making difficulties and negative emotional states. Journal of Career Development, 48(4), 537–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, R. K., Wagner, B., & Dahl, D. (2004). Reducing career indecisiveness in adults. International Journal of Disability Community and Rehabilitation, 3(2). Available online: https://www.ucalgary.ca/uofc/Others/ijdcr/VOL03_02_CAN/articles/austin.shtml (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R. A. (2008). The role of affect in the entrepreneurial process. Academy of Management Review, 33(2), 328–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumeister, R. F., Vohs, K. D., Nathan DeWall, C., & Zhang, L. (2007). How emotion shapes behavior: Feedback, anticipation, and reflection, rather than direct causation. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 11(2), 167–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belchior, R. F., & Lyons, R. (2021). Explaining entrepreneurial intentions, nascent entrepreneurial behavior and new business creation with social cognitive career theory—A 5-year longitudinal analysis. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 17(4), 1945–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brousseau, K. R., Driver, M. J., Eneroth, K., & Larsson, R. (1996). Career pandemonium: Realigning organizations and individuals. Academy of Management Executive, 10(4), 52–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, O., & Shepherd, D. A. (2015). Different strokes for different folks: Entrepreneurial narratives of emotion, cognition, and making sense of business failure. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(2), 375–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardon, M. S., Foo, M., Shepherd, D., & Wiklund, J. (2012). Exploring the heart: Entrepreneurial emotion is a hot topic. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(1), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, N. M., Gartner, W. B., & Reynolds, P. D. (1996). Exploring start-up event sequences. Journal of Business Venturing, 11(3), 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosina, E., Frey, E., Corbett, A., & Greenberg, D. (2024). From negative emotions to entrepreneurial mindset: A model of learning through experiential entrepreneurship education. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 23(1), 88–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidsson, P. (2006). Nascent entrepreneurship: Empirical studies and developments. Foundations and Trends in Entrepreneurship, 2(1), 1–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, K. L., Wright, S., & Forray, J. M. (2020). Experiential learning and the moral duty of business schools. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 19(4), 569–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghanpour Farashah, A. (2015). The effects of demographic, cognitive and institutional factors on development of entrepreneurial intention: Toward a socio-cognitive model of entrepreneurial career. Journal of International Entrepreneurship, 13(4), 452–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, E. J., & Shepherd, D. A. (2002). Self-employment as a career choice: Attitudes, entrepreneurial intentions, and utility maximization. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 26(3), 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, M. D. (2011). Emotions and entrepreneurial opportunity evaluation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 35(2), 375–393.23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, M.-D., Uy, M. A., & Baron, R. A. (2009). How do feelings influence effort? An empirical study of entrepreneurs’ affect and venture effort. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(4), 1086–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating Structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gielnik, M. M., Bledow, R., & Stark, M. S. (2020). A dynamic account of self-efficacy in entrepreneurship. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(5), 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gollwitzer, P. M. (1999). Implementation intentions: Strong effects of simple plans. American Psychologist, 54(7), 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hechtlinger, S., Levin, N., & Gati, I. (2019). Dysfunctional career decision-making beliefs: A multidimensional model and measure. Journal of Career Assessment, 27(2), 209–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaffka, G., & Krueger, N. (2018). The entrepreneurial ‘mindset’: Entrepreneurial intentions from the entrepreneurial event to neuroentrepreneurship. In G. Javadian, V. K. Gupta, & D. K. Dutta (Eds.), Foundational research in entrepreneurship studies: Insightful contributions and future pathways (pp. 203–224). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Kaffka, G., & Krueger, N. (2023). Making the meaningful moments visible–about the real-time study of entrepreneurial sensemaking. In Nurturing modalities of inquiry in entrepreneurship research: Seeing the world through the eyes of those who research (Vol. 17, pp. 109–126). Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Kakouris, A., & Liargovas, P. (2021). On the about/for/through framework of entrepreneurship education: A critical analysis. Entrepreneurship Education and Pedagogy, 4(3), 396–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakouris, A., & Morselli, D. (2020). Addressing the pre/post-university pedagogy of entrepreneurship coherent with learning theories. In Entrepreneurship education: A lifelong learning approach (pp. 35–58). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Kakouris, A., Tampouri, S., Kaliris, A., Mastrokoukou, S., & Georgopoulos, N. (2023). Entrepreneurship as a career option within education: A critical review of psychological constructs. Education Sciences, 14(1), 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, S. (2020). The role of entrepreneurial passion in the formation of students’ entrepreneurial intentions. Applied Economics, 52(3), 331–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F., Zhao, L., & Tsai, C. H. (2020). The relationship between entrepreneurial intention and action: The effects of fear of failure and role mod-el. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotta, I., Veres, A., Farcas, S., Kiss, S., & Bernath-Vincze, A. (2021). My fate is my decision: The differential effects of fate and criticality of decision beliefs on career decision making self-efficacy. European Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 4, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronholz, J., & Osborn, D. S. (2022). Dysfunctional career thoughts, profile elevation, and RIASEC skills of career counseling clients. Journal of Employment Counseling, 59(2), 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N. (2020). Entrepreneurial potential and potential entrepreneurs: 25 years on. Journal of the International Council for Small Business, 1(1), 52–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, N. F. (2017). Entrepreneurial intentions are dead: Long live entrepreneurial intentions. In Revisiting the entrepreneurial mind (pp. 13–34). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Krumboltz, J. D. (1990, March 27–29). Helping individuals change dysfunctional career beliefs. Annual convention of the American Association for Counseling and Development, Orlando, FL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Kuratko, D. F., Fisher, G., & Audretsch, D. B. (2021). Unraveling the entrepreneurial mindset. Small Business Economics, 57(4), 1681–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lackéus, M. (2014). An emotion based approach to assessing entrepreneurial education. The International Journal of Management Education, 12(3), 374–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laouiti, R., Haddoud, M. Y., Nakara, W. A., & Onjewu, A.-K. E. (2022). A gender-based approach to the influence of personality traits on entrepreneurial intention. Journal of Business Research, 142, 819–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lease, S. H. (2004). Effect of locus of control, work knowledge, and mentoring on career decision-making difficulties: Testing the role of race and academic institution. Journal of Career Assessment, 12, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R. W., & Brown, S. D. (2013). Social cognitive model of career self-management: Toward a unifying view of adaptive career behavior across the life span. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60(4), 557–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R. W., Brown, S. D., & Hackett, G. (1994). Toward a Unifying Social Cognitive Theory of Career and Academic Interest, Choice, and Performance. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 45(1), 79–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R. W., Ireland, G. W., Penn, L. T., Morris, T. R., & Sappington, R. (2017). Sources of self-efficacy and outcome expectations for career exploration and decision-making: A test of the social cognitive model of career self-management. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 99, 107–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.-K., Nguyen, V. H. A., & Caputo, A. (2022). Unveiling the role of entrepreneurial knowledge and cognition as antecedents of entrepreneurial intention: A meta-analytic study. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 18(4), 1623–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liguori, E., Winkler, C., Vanevenhoven, J., Winkel, D., & James, M. (2020). Entrepreneurship as a career choice: Intentions, attitudes, and outcome expectations. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 32(4), 311–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X., Xiong, Y., Lv, X., & Shan, B. (2022). Emotion in the area of entrepreneurship: An analysis of research hotspots. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 922148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matherne Iii, C. F., Bendickson, J. S., Santos, S. C., & Taylor, E. C. (2020). Making sense of entrepreneurial intent: A look at gender and entrepreneurial personal theory. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 26(5), 989–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, J. E., Peterson, M., Mueller, S. L., & Sequeira, J. M. (2009). Entrepreneurial self-efficacy: Refining the measure. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(4), 965–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, G., Holden, R., & Walmsley, A. (2010). From student to entrepreneur: Towards a model of graduate entrepreneurial career-making. Journal of Education and Work, 23(5), 389–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nabi, G., Walmsley, A., Liñán, F., Akhtar, I., & Neame, C. (2018). Does entrepreneurship education in the first year of higher education develop entrepreneurial intentions? The role of learning and inspiration. Studies in Higher Education, 43(3), 452–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newman, A., Obschonka, M., Schwarz, S., Cohen, M., & Nielsen, I. (2019). Entrepreneurial self-efficacy: A systematic review of the literature on its theoretical foundations, measurement, antecedents, and outcomes, and an agenda for future research. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 110, 403–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nwibe, K. J., & Ogbuanya, T. C. (2024). Emotional intelligence and entrepreneurial intention among university undergraduates in Nigeria: Exploring the mediating roles of self-efficacy domains. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 13(1), 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owens, R. L., Flores, L. Y., Kopperson, C., & Allan, B. A. (2019). Infusing positive psychological interventions into career counseling for diverse populations. The Counseling Psychologist, 47(2), 291–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L., Li, J., Du, T., Hu, Z. A., & Ye, J. H. (2025). How positive emotions affect entrepreneurial intention of college students: A moderated mediation model. Heliyon, 11(4), e42842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paray, Z. A., & Kumar, S. (2020). Does entrepreneurship education influence entrepreneurial intention among students in HEI’s?: The role of age, gender and degree background. Journal of International Education in Business, 13(1), 55–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice (4th ed.). SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Politis, D. (2005). The process of entrepreneurial learning: A conceptual framework. Entrepreneurship Theory And Practice, 29(4), 399–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynolds, P. D., & Curtin, R. T. (2008). Business creation in the United States: Panel study of entrepreneurial dynamics II initial assessment. Foundations and Trends in Entrepreneurship, 4(3), 155–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigoni, D., Demanet, J., & Sartori, G. (2015). Happiness in action: The impact of positive affect on the time of the conscious intention to act. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampson, J. P., McClain, M., Musch, E., & Reardon, R. C. (2013). Variables affecting readiness to benefit from career interventions. The Career Development Quarterly, 61(2), 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarasvathy, S. D. (2001). Causation and effectuation: Toward a theoretical shift from economic inevitability to entrepreneurial contingency. Academy of management Review, 26(2), 243–263. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders, D. E., Peterson, G. W., Sampson, J. P., & Reardon, R. C. (2000). Relation of depression and dysfunctional career thinking to career indecision. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 56(2), 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savickas, M. L. (2013). Career construction theory and practice. In R. W. Lent, & S. D. Brown (Eds.), Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work (pp. 147–183). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Seo, J., Kim, J., & Mesquita, L. F. (2024). Does vicarious entrepreneurial failure induce or discourage one’s entrepreneurial intent? A mediated model of entrepreneurial self-efficacy and identity aspiration. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 30(1), 52–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, D. A. (2003). Learning from business failure: Propositions of grief recovery for the self-employed. Academy of Management Review, 28(2), 318–328. [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd, D. A. (2004). Educating entrepreneurship students about emotion and learning from failure. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 3(3), 274–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinnar, R. S., Hsu, D. K., & Powell, B. C. (2014). Self-efficacy, entrepreneurial intentions, and gender: Assessing the impact of entrepreneurship education longitudinally. The International Journal of Management Education, 12(3), 561–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidiropoulou-Dimakakou, D., Mylonas, K., Argyropoulou, K., & Tampouri, S. (2012). Career decision-making difficulties, dysfunctional thinking and generalized self-efficacy of university students in greece. World Journal of Education, 2(1), 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Thompson, E. R. (2009). Individual entrepreneurial intent: Construct clarification and development of an internationally reliable metric. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 33(3), 669–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukil, M. I., Ullah, M. S., Islam, K. Z., Razzak, B. M., Saridakis, G., & Alamoudi, S. M. (2025). Examining the emotion–entrepreneurial intention link using the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 32(2), 344–370. [Google Scholar]

- Vanevenhoven, J., & Liguori, E. (2013). The impact of entrepreneurship education: Introducing the entrepreneurship education project. Journal of Small Business Management, 51(3), 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walmsley, A., Decker-Lange, C., & Lange, K. (2022). Conceptualising the entrepreneurship education and employability nexus. In Theorising under-graduate entrepreneurship education: Reflections on the development of the entrepreneurial mindset (pp. 97–114). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Weick, K. E. (1995). Sensemaking in organizations. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, F., Kickul, J., Marlino, D., Barbosa, S. D., & Griffiths, M. D. (2009). An analysis of the role of gender and self-efficacy in developing female entrepreneurial interest and behavior. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 14(02), 105–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zampetakis, L. A., Kafetsios, K., Bouranta, N., Dewett, T., & Moustakis, V. S. (2009). On the relationship between emotional intelligence and entrepreneurial attitudes and intentions. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 15(6), 595–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H., Seibert, S. E., & Hills, G. E. (2005). The mediating role of self-efficacy in the development of entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(6), 1265–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Mean | SD | GENDER | AGE | NEB | INT | BCD | POS. EMOTIONS | NEG. EMOTIONS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GENDER | 1.56 | 0.48 | - | ||||||

| AGE | 34.55 | 12.22 | 61.038 a | - | |||||

| NEB | 1.48 | 2.69 | 24.506 * | 0.252 *** | - | ||||

| INT | 3.90 | 1.43 | 0.373 *** | 0.677 | |||||

| BCD | 3.37 | 1.07 | 0.225 *** | 0.558 | |||||

| POS. EMOTIONS | 3.44 | 1.06 | 0.155 ** | 0.297 *** | 0.494 *** | 0.862 | |||

| NEG. EMOTIONS | 2.77 | 1.09 | 0.138 * | −0.173 ** | 0.854 |

| Model 0 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | t-value | Β | t-value | Β | t-value | Β | t-value | |

| Control variables | ||||||||

| GENDER | −0.100 a | −1.736 | −0.061 | −1.181 | −0.070 | −1.297 | −0.077 | −1.411 |

| AGE | 0.091 | 1.577 | 0.042 | 0.818 | 0.046 | 0.848 | 0.044 | 0..822 |

| Emotional states | ||||||||

| PE | 0.483 *** | 9.536 | 0.477 *** | 9.374 | 0.472 *** | 9.075 | ||

| NE | −0.015 | −0.3 | −0.001 | −0.010 | −0.009 | −0.174 | ||

| BCD | ||||||||

| CHANCE | −0.017 | −0.276 | −0.002 | −0.029 | ||||

| OTH | −0.093 | −1.360 | −0.102 | −1.486 | ||||

| CRIT | −0.086 | −1.476 | −0.053 | −0.901 | ||||

| PH | 0.071 | 1.087 | 0.081 | 1.207 | ||||

| GS | 0.011 | 0.180 | 0.029 | 0.464 | ||||

| Interactions (significant) | ||||||||

| NE × CRIT | 0.173 ** | 2.976 | ||||||

| ΔF | 3.185 * | 45.565 *** | 1.158 | 2.029 * | ||||

| ΔR2 | 0.021 | 0.23 | 0.015 | 0.049 | ||||

| Model 0 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Β | t-value | Β | t-value | Β | t-value | Β | t-value | |

| Control variables | ||||||||

| GENDER | −0.135 * | −2.375 | −0.106 a | −1.945 | −0.097 a | −1.698 | −0.082 | −1.428 |

| AGE | 0.181 ** | 3.196 | 0.155 ** | 2.846 | 0.175 ** | 3.066 | 0.167 ** | 2.927 |

| Entrepreneurial intention | ||||||||

| ΙΝΤ | 0.283 *** | 5.206 | 0.286 *** | 5.206 | 0.25 *** | 4.398 | ||

| BCD | ||||||||

| CHANCE | −0.136 * | −2.054 | −0.129 a | −1.947 | ||||

| OTH | 0.112 | 1.528 | 0.103 | 1.398 | ||||

| CRIT | −0.054 | −0.856 | −0.025 | −0.395 | ||||

| PH | −0.031 | −0.447 | −0.021 | −0.295 | ||||

| GS | 0.017 | 0.256 | 0.01 | 0.142 | ||||

| Interactions (significant) | ||||||||

| INT × CHANCE | −0.094 b | −1.533 | ||||||

| INT × CRIT | −0.116 a | −1.716 | ||||||

| ΔF | 9.138 *** | 27.102 *** | 1.094 | 1.898 a | ||||

| ΔR2 | 0.058 | 0.079 | 0.016 | 0.027 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tampouri, S.; Kakouris, A.; Liargovas, P.; Krueger, N.; Sarri, K. Entrepreneurial Career: A Critical Occupational Decision. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1450. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111450

Tampouri S, Kakouris A, Liargovas P, Krueger N, Sarri K. Entrepreneurial Career: A Critical Occupational Decision. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1450. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111450

Chicago/Turabian StyleTampouri, Sofia, Alexandros Kakouris, Panagiotis Liargovas, Norris Krueger, and Katerina Sarri. 2025. "Entrepreneurial Career: A Critical Occupational Decision" Education Sciences 15, no. 11: 1450. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111450

APA StyleTampouri, S., Kakouris, A., Liargovas, P., Krueger, N., & Sarri, K. (2025). Entrepreneurial Career: A Critical Occupational Decision. Education Sciences, 15(11), 1450. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111450