Emotional Intelligence, Creativity, and Subjective Well-Being: Their Implication for Academic Success in Higher Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

- To identify which cognitive-emotional variables among those studied are most strongly associated with academic success.

- To determine the influence of these variables on the likelihood of academic success.

- To describe the profile of the student who achieves academic success.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Procedure

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

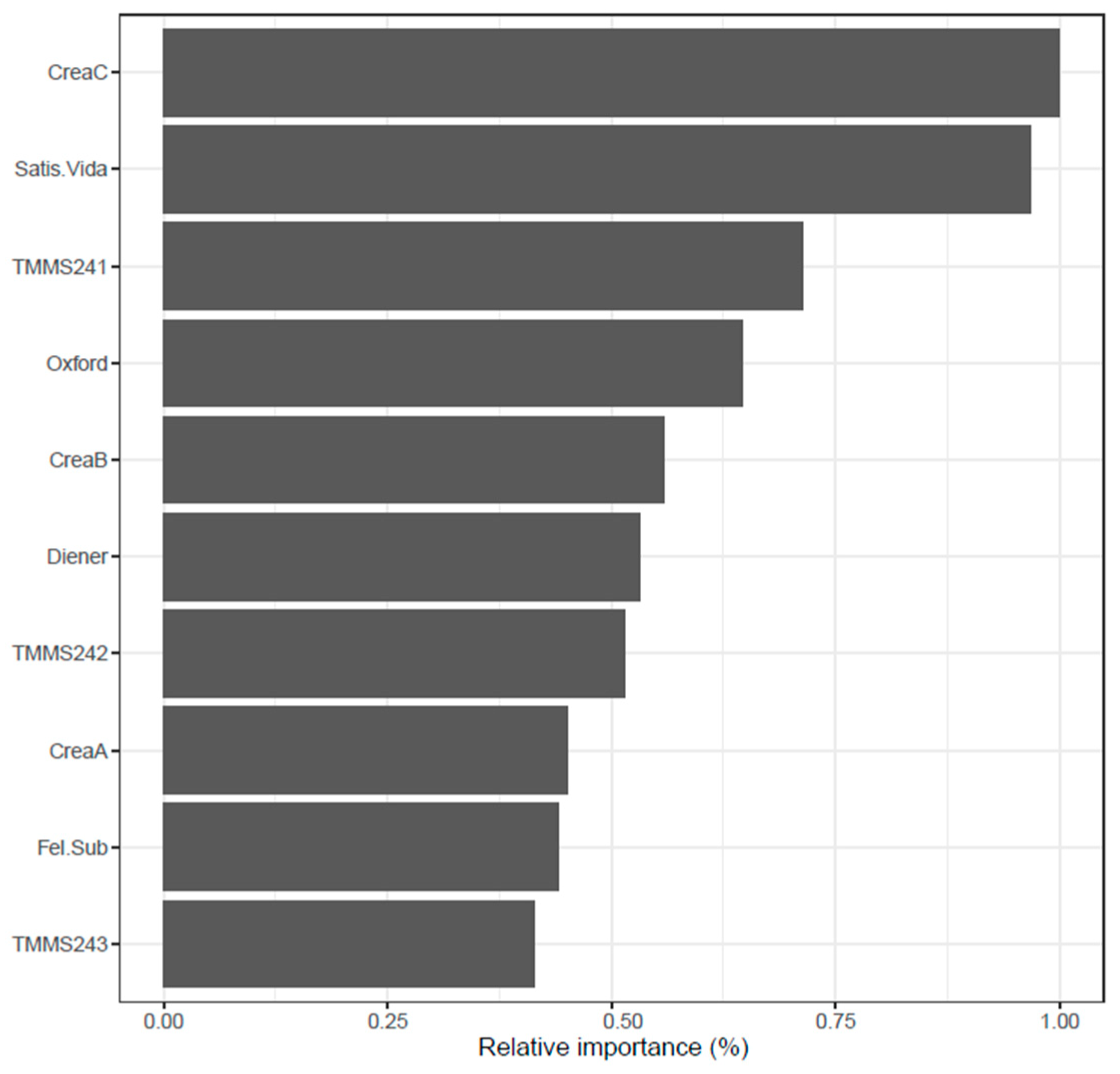

3.1. Cognitive-Emotional Variables and Their Importance in Relation to Academic Success

3.2. Cognitive-Emotional Variables and Their Impact on Academic Success

3.3. Profile of the Academically Successful Student

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Acar, S., Tadik, H., Myers, D., van der Sman, C., & Uysal, R. (2021). Creativity and well being: A meta analysis. The Journal of Creative Behavior, 55(3), 738–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Z., Asim, M., & Pellitteri, J. (2019). Emotional intelligence predicts academic achievement in Pakistani management students. The International Journal of Management Education, 17(2), 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akin, A., & Akin, U. (2016). Academic potential beliefs and feelings and life satisfaction: The mediator role of social self-efficacy. International Journal of Social Psychology, 31(3), 500–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpur, U. (2023). Creativity and academic achievement: A meta-analysis. European Journal of Educational Sciences, 10(2), 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldas Manzano, J., & Uriel Jiménez, E. (2017). Análisis multivariante aplicado con R. Ediciones Paraninfo. [Google Scholar]

- Alzoubi, A. M. A., Al Qudah, M. F., Albursan, I. S., Bakhiet, S. F. A., & Alfnan, A. A. (2021). The predictive ability of emotional creativity in creative performance among university students. SAGE Open, 11(2), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arhuis Inca, W. S. (2019). Social skills, psychological well-being and academic performance in students of a private university in Chimbote, 2018 [Master’s thesis, Universidad Privada Antenor Orrego]. Available online: https://renati.sunedu.gob.pe/handle/renati/373919 (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Balkis, M. (2013). Academic procrastination, academic life satisfaction and academic achievement: The mediation role of rational beliefs about studying. Journal of Cognitive y Behavioral Psychotherapies, 13(1), 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belmonte, V. M. (2013). Inteligencia emocional y Creatividad: Factores predictores del rendimiento académico [Ph.D. thesis, University of Murcia]. Publications Service. [Google Scholar]

- Brauer, R., Ormiston, J., & Beausaert, S. (2025). Creativity-fostering teacher behaviors in higher education: A transdisciplinary systematic literature review. Review of Educational Research, 95(5), 899–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. (2001). Random forests. Machine Learning, 45(1), 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bücker, S., Nuraydin, S., Simonsmeier, B. A., Schneider, M., & Luhmann, M. (2018). Subjective well-being and academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Journal of Research in Personality, 74, 83–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero García, P. Á., Galeano Terán, A. S., & Constante Amores, I. A. (2024). Práctica deportiva saludable, resiliencia del profesorado e inclusión educativa en Imbabura (Ecuador). Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado (REIFOP), 27(1), 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero-García, P. Á., & Sánchez Ruiz, S. (2021). Creativity and life satisfaction in Spanish university students. Effects of an emotionally positive and creative program. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 746154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero-García, P. Á., & Sánchez Ruiz, S. (2022). Educar “en y con” el pensamiento crítico. Un estudio diferencial por género y edad en estudiantes universitarios. In D. Moya López, & A. I. Nogales Bocio (Eds.), Del periodismo a los prosumidores. Mensajes, lenguajes y sociedad. (Chapter 14, pp. 240–259). Contemporary Knowledge Collection. Dyckinson. [Google Scholar]

- Caballero-García, P. Á., Sánchez Ruiz, S., & Belmonte Almagro, M. L. (2019). Análisis de la creatividad de los estudiantes universitarios. Diferencias por género, edad y elección de estudios. Educación XX1, 22(2), 213–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, A., Converse, P. E., & Rodgers, W. L. (1976). The quality of American life: Perceptions, evaluations, and satisfactions. Russel Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Canto, Y. E., Ferrer, E. Z., & Díaz Gervasi, G. M. (2021). Disposición, habilidades del pensamiento crítico y éxito académico en estudiantes universitarios: Metaanálisis. Revista Complutense de Educación, 32(4), 525–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carranza Esteban, R. F., Hernández, R. M., & Alhuay-Quispe, J. (2017). Bienestar psicológico y rendimiento académico en estudiantes de pregrado de psicología. Revista Internacional de Investigación en Ciencias Sociales, 13(2), 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Carrillo, Y. M., Pérez, J., Roa, S. C., Morales, Y., Rylander, J., & Méndez, T. J. (2020). Inteligencia emocional y rendimiento académico en alumnos universitarios. Revista Mexicana Medicina Forense, 5(Suppl. 3), 161–164. Available online: https://revistas.utm.edu.ec/index.php/Recus/article/view/3470/5875 (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Castro, M., & Lizasoain, L. (2012). Las técnicas de modelización estadística en la investigación educativa: Minería de datos, modelos de ecuaciones estructurales y modelos jerárquicos lineales. Revista Española de Pedagogía, 70(251), 131–148. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23766443 (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Chang, Q., Han, H., & Hu, D. (2025). Meta-analysis of supervisor support and postgraduate creativity: Evidence from a sample of Chinese students. Frontiers in Education, 10, 1490322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiecher, A. C., Elisondo, R. C., Paoloni, P. V., & Donolo, D. S. (2018). Creatividad, género y rendimiento académico en ingresantes de ingeniería. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación Superior, 9(24), 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cieza, L., & Palomino, R. P. (2019). Resiliencia y disposición hacia el pensamiento crítico en estudiantes de una universidad privada de Lima Metropolitana [Ph.D. thesis, Women’s University of the Sacred Heart]. Institutional Repository. [Google Scholar]

- Corbalán Berná, F. J., Martínez, F., Donolo, D., Alonso, C., Tejerina, M., & Limiñana, R. M. (2003). Crea. In teligencia creativa. Una medida cognitiva de la creatividad. TEA Editions. [Google Scholar]

- Day, C., & Gu, Q. (2015). Educadores resilientes, escuelas resilientes: Construir y sostener la calidad educativa en tiempos difíciles. Narcea Editions. [Google Scholar]

- Deniz, M. E., Tras, Z., & Aydogan, D. (2009). An investigation of academic procrastination, locus of control and emotional intelligence. Spring, 9, 623–632. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E., Emmons, R., Larsen, R., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 1105–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felix-Mena, A., Martínez-Rodríguez, A., & Reche-García, C. (2021). Resilience and burnout in dual career. Cultura, Ciencia y Deporte, 16(47), 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Berrocal, P., Extremera, N., & Palomera, R. (2008). Emotional intelligence as a crucial ability on educational context. In A. Valle, & J. C. Nuñez (Eds.), Handbook of instructional resources and their applications in the classroom. Nova Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Berrocal, P., Extremera, N., & Ramos, N. (2004). Validity and reliability of the Spanish modified version of the Trait Meta-Mood Scale. Psychological Report, 94, 751–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Lasarte, O., Ramos-Díaz, E., & Saez, I. (2019). Rendimiento académico, apoyo social percibido e inteligencia emocional en la universidad. EJIHPE: European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 9(1), 39–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández Mellizo, M., & Constante Amores, A. (2020). Determinantes del rendimiento académico de los estudiantes de nuevo acceso a la Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Revista de Educación, 387, 213–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, M., Allan, S., Arnold, C., Eleftheriadis, D., Alvarez-Jimenez, M., Gumley, A., & Gleeson, J. F. (2022). Digital interventions for psychological well-being in university students: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 24(9), e39686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajda, A., Karwowski, M., & Beghetto, R. A. (2017). Creativity and academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 109(2), 269–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, J., & Wagenaar, R. (Eds.). (2003). Tuning educational structures in Europe. University of Deusto. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez Álvarez, P. D., & García Valenzuela, V. M. (2022). Análisis correlacional entre el rendimiento académico y el bienestar psicológico de estudiantes universitarios de Sonora, México. Eureka. Revista Científica de Psicología, 19(2), 234–251. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, H., Zhou, Z., & Ma, F. (2025). Effect of training programs on the creativity of university students: A multi-level meta-analysis. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 56, 101779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastie, T., Tibshirani, R., & Friedman, J. H. (2009). The elements of statistical learning: Data mining, inference, and prediction (2nd ed.). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hills, P., & Argyle, M. (2002). The Oxford Happiness Questionnaire: A compact scale for the measurement of psychological well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 33(7), 1073–1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, C., Armitage, J., Hood, B., & Jelbert, S. (2022). A systematic review of the effect of university positive psychology courses on student psychological wellbeing. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1023140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsieh, C. C., Gunawan, I., & Li, H. C. (2023). Una revisión bibliométrica de la investigación sobre liderazgo educativo: Mapeo científico de la literatura de 1974 a 2020. Revista de Educación, 401, 293–324. [Google Scholar]

- Idrogo Zamora, D. I., & Asenjo Alarcón, J. A. (2021). Relación entre inteligencia emocional y rendimiento académico en estudiantes universitarios peruanos. Revista de Investigación Psicológica, (26), 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto de Inteligencia Emocional y Neurociencia aplicada. (2021). I Estudio Nacional sobre la educación emocional en los Colegios en España. Idiena. Available online: https://www.observatoriodelainfancia.es/ficherosoia/documentos/7470_d_I-Estudio-Educacion-Emocional-en-los-Colegios-en-Espana-2021.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Jiménez Morales, M. I., & López Zafra, E. (2013). Impacto de la inteligencia emocional percibida, actitudes sociales y expectativas del profesor en el rendimiento académico. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 11(1), 75–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R. M., & Saccuzzo, D. P. (2009). Psychological testing: Principles applications and issues (7th ed.). Wadsworth, Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Kleeberg-Hidalgo, F., & Ramos-Ramírez, J. C. (2009). Aplicación de las técnicas de muestreo en los negocios y la industria. Ingeniería Industrial, 27(027), 11–40. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12724/2462 (accessed on 16 November 2025). [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kuhn, M., & Johnson, K. (2013). Applied predictive modeling. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamas, H. A. (2015). Sobre el rendimiento escolar. Propósitos y Representaciones, 3(1), 313–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, R., Gullickson, A., & Harrison, J. A. (2025). Inequality in measuring scholarly success: Variation in the h-index within and between disciplines. PLoS ONE, 20(1), e0316913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limiñana Gras, R. M., Corbalán, J., & Sánchez López, M. P. (2010). Creatividad y estilos de personalidad: Aproximación a un perfil creativo en estudiantes universitarios. Anales de Psicología, 26(2), 273–278. [Google Scholar]

- López Martín, E., & Ardura Martínez, D. (2023). El tamaño del efecto en la publicación científica. Educación XX1, 26(1), 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Roldán, P., & Fachelli, S. (2015). Metodología de la investigación social cuantitativa. Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona (Spain). Available online: https://ddd.uab.cat/pub/caplli/2015/142929/metinvsoccua_cap3-12a2016v2.pdf (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Lyubomirsky, S., & Lepper, H. S. (1999). A measure of subjective happiness: Preliminary reliability and construct validation. Social Indicators Research, 46(2), 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCann, C., Jiang, Y., Brown, L. E., Double, K. S., Bucich, M., & Minbashian, A. (2020). Emotional intelligence predicts academic performance: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 146(2), 150–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maharaj, P., & Ramsaroop, A. (2024). Enhancing emotional intelligence for well-being in higher education: Supporting SDG 3 amid adversity. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 22, 2705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manso, J., & Thoillez, B. (2015). La competencia emprendedora como tendencia educativa supranacional en la Unión Europea. Bordón. Revista de Pedagogía, 67(1), 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderi, H., Abdullah, R., Aizan, H. T., Sharir, J., & Kumar, V. (2010). Relationship between creativity and academic achievement: A study of gender differences. Journal of American Science, 6(1), 181–190. [Google Scholar]

- Orejarena Silva, H. A. (2020). Relación entre inteligencia emocional, estilos de aprendizaje y rendimiento académico en un grupo de estudiantes de psicología. Inclusión y Desarrollo, 7(2), 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osornio, C. L., Sánchez, T. H., Heshiki, H. L., & Veladez, N. S. (2011). El bienestar psicológico, predictor del rendimiento académico en estudiantes de la carrera de médico cirujano. Archivos en Medicina Familiar, 13(3), 111–116. [Google Scholar]

- Panicello, V. (2022). La creatividad impulsa el futuro. Universitat Carlemany. Planeta Training and Universities. [Google Scholar]

- Pardo, M., & Ruiz, M. (2013). Análisis de Datos en Ciencias Sociales y de la Salud III. Síntesis. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, J. D. A., Summerfeldt, L. J., Hogan, M. J., & Majeski, S. A. (2004). Emotional intelligence and academic success: Examining the transition from high school to university. Personality and Individual Differences, 36(1), 163–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peña, I., Guerrero, M., González-Pernía, J. L., & Montero, J. (2018). GEM, Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, Informe España. 2017–2018. University of Cantabria, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez Ordóñez, C., Torres Martín, J. L., Castro Martínez, A., & Villena Alarcón, E. (2021). La creatividad en la universidad española. Un análisis crítico de los planes de estudio, la actividad docente y las necesidades del sector profesional en los grados de comunicación audiovisual, publicidad y relaciones públicas. Icono14, 19(2), 36–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez Pérez, N., & Castejón, J. L. (2006). Relaciones entre la inteligencia emocional y el cociente intelectual con el rendimiento académico en estudiantes universitarios. Revista Electrónica de Motivación y Emoción REME, 9(22), 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Puertas Molero, P., Zurita Ortega, F., Chacón Cuberos, R., Castro Sánchez, M., Ramírez Granizo, I., & González Valero, G. (2020). La inteligencia emocional en el ámbito educativo: Un metaanálisis. Anales de Psicología, 36(1), 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quílez-Robres, A., Usán, P., Lozano-Blasco, R., & Salavera, C. (2023). Emotional intelligence and academic performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 49, 101355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez, P. E., & Fuentes, C. A. (2013). Felicidad y rendimiento académico: Efecto moderador de la felicidad sobre indicadores de selección y rendimiento académico de alumnos de ingeniería comercial. Formación Universitaria, 6(3), 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Raschka, S., & Mirjalili, V. (2019). Python machine learning: Machine learning and deep learning with Python, scikit-learn, and TensorFlow 2. Packt Publishing Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Romero Caballero, S., Hernández Sánchez, I., Barrera Villarreal, R., & Mendoza Rojas, A. (2022). Inteligencia emocional y desempeño académico en el área de las matemáticas durante la pandemia. Revista de Ciencias Sociales, 28(2), 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar Almeida, P. A. (2021). Inteligencia emocional y su influencia en el rendimiento académico en estudiantes universitarios. Revista de Investigación Enlace Universitario, 20(2), 88–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salovey, P., & Mayer, J. D. (1990). Emotional intelligence. Imagination, Cognition, and Personality, 9, 185–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Ruiz, S. (2020). Inteligencia emocional, creatividad, bienestar subjetivo y rendimiento académico en alumnos universitarios [Ph.D. thesis, Camilo José Cela University]. Institutional repository. [Google Scholar]

- Sospedra Baeza, M. J., Martínez-Álvarez, I., & Hidalgo-Fuentes, S. (2022). Inteligencias múltiples, emociones y creatividad en estudiantes universitarios españoles de primer curso. Revista Digital de Investigación en Docencia Universitaria, 16(2), e1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strobl, C., Malley, J., & Tutz, G. (2009). An introduction to recursive partitioning: Rationale, application, and characteristics of classification and regression trees, bagging, and random forests. Psychological Methods, 14(4), 323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supervía, P., & Bordás, C. (2019). Relaciones de la inteligencia emocional, burnout y compromiso académico con el rendimiento escolar de estudiantes adolescentes. Archivos de Medicina (Manizales), 19(2), 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (2022). Re|pensar las políticas para la creatividad. UNESCO. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/reports/reshaping-creativity/2022/es/descargar-informe (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- Vugteveen, J., Figueroa Esquivel, F., & Luijer, C. (2025). Defining student success as a multidimensional concept: A scoping review. International Journal of Educational Research Open, 9, 100518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Economic Forum (WEF). (2020). The future of jobs report 2020. World Economic Forum. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/publications/the-future-of-jobs-report-2020/ (accessed on 16 November 2025).

- World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki (WMADH). (2018). Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human subjects. International Journal of Medical and Surgical Sciences, 1(4), 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H., & Wang, J. (2025). Enhancing college students’ creativity through virtual reality technology: A systematic literature review. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 12(1), 693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Success | 153 | 51 |

| Failure | 147 | 49 |

| Mean | Standard Deviation | Coefficient of Variation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TMMS-24 1 | 27.9367 | 6.396 | 0.237 |

| TMMS-24 2 | 27.186 | 6.521 | 0.240 |

| TMMS-24 3 | 28.086 | 6.142 | 0.219 |

| Crea A | 37.246 | 25.703 | 0.690 |

| Crea B | 44.500 | 27.246 | 0.612 |

| Crea C | 68.803 | 27.080 | 0.394 |

| Oxford | 4.508 | 0.621 | 0.138 |

| Subjective happiness | 5.000 | 0.975 | 0.195 |

| Life satisfaction | 7.615 | 1.503 | 0.197 |

| Diener | 5.372 | 1.036 | 0.193 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

| 1. TMMS-24 1 | |||||||||

| 2. TMMS-24 2 | 0.30 ** | ||||||||

| 3. TMMS-24 3 | 0.09 | 0.44 ** | |||||||

| 4. Crea A | −0.11 | −0.10 | −0.06 | ||||||

| 5. Crea B | −0.06 | −0.07 | −0.10 | 0.66 ** | |||||

| 6. Crea C | −0.02 | −0.12 * | −0.07 | 0.60 ** | 0.70 ** | ||||

| 7. Oxford | 0.09 | 0.49 ** | 0.46 ** | −0.02 | −0.04 | −0.03 | |||

| 8. Subjective happiness | 0.00 | 0.43 ** | 0.46 ** | −0.02 | −0.04 | −0.07 | 0.66 ** | ||

| 9. Life satisfaction | 0.02 | 0.44 ** | 0.36 ** | 0.00 | 0.02 | −0.05 | 0.65 ** | 0.68 ** | |

| 10. Diener | 0.05 | 0.43 ** | 0.31 ** | −0.04 | 0.02 | −0.05 | 0.61 ** | 0.57 ** | 0.69 ** |

| Coefficient (ES) | Odds Ratio | Lower Limit | Upper Limit | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Creativity | 0.011 (0.04) | 1.011 * | 1.003 | 1.021 |

| Life Satisfaction | 0.190 (0.082) | 1.209 * | 1.022 | 1.408 |

| Intercept | −2.2514 (0.734) | 0.105 ** | −0.041 | −0.565 |

| Pseudo R2 | 4% |

| Correctly Classified Cases | |

|---|---|

| Random Forest | 0.64 |

| Binary Logistic Regression | 0.59 |

| Decision Tree | 0.63 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Caballero García, P.Á.; Sánchez Ruiz, S.; Constante Amores, A. Emotional Intelligence, Creativity, and Subjective Well-Being: Their Implication for Academic Success in Higher Education. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1562. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111562

Caballero García PÁ, Sánchez Ruiz S, Constante Amores A. Emotional Intelligence, Creativity, and Subjective Well-Being: Their Implication for Academic Success in Higher Education. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1562. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111562

Chicago/Turabian StyleCaballero García, Presentación Ángeles, Sara Sánchez Ruiz, and Alexander Constante Amores. 2025. "Emotional Intelligence, Creativity, and Subjective Well-Being: Their Implication for Academic Success in Higher Education" Education Sciences 15, no. 11: 1562. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111562

APA StyleCaballero García, P. Á., Sánchez Ruiz, S., & Constante Amores, A. (2025). Emotional Intelligence, Creativity, and Subjective Well-Being: Their Implication for Academic Success in Higher Education. Education Sciences, 15(11), 1562. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111562