1. Introduction

The rapid acceleration of digital education globally has foregrounded the importance of teacher digital competencies, particularly in rural and under-resourced contexts where infrastructure and support systems are often lacking. While the South African Department of Basic Education (DBE) has increasingly prioritised digital integration in schools, rural teachers continue to experience systemic barriers in adopting and meaningfully implementing digital technologies in their teaching practice (

Aluko & Ooko, 2022;

Nyathi & Joseph, 2024). In Saudi Arabia,

Althubyani (

2024) similarly reported that teacher digital competence was moderate overall, with contextual factors such as workload and access strongly influencing adoption. Similar disparities have been observed in Nigeria, where teachers in public schools struggled with access and training in Microsoft tools, unlike their private school counterparts (

Abdullahi & Mohammed, 2022). These challenges are compounded by uneven professional development (PD) opportunities, generational and gender disparities in digital fluency, and insufficient institutional support mechanisms (

Wade & Mestry, 2021;

Flowers & Tanner, 2024).

International literature reflects similar patterns in low- and middle-income countries, where digital teacher training initiatives are often fragmented and short-term, resulting in inconsistent uptake and limited long-term impact (

Soekamto et al., 2022;

Xu, 2024). In response, scholars have called for more embedded, differentiated, and sustained models of professional development tailored to the contextual realities of rural educators (

Korsager et al., 2022;

Okoed & Bileti, 2024).

In the South African context, studies show that rural teachers remain enthusiastic about acquiring digital skills, yet they face major constraints, including unreliable internet access, device shortages, and training formats that fail to reflect rural pedagogical needs (

Aluko & Ooko, 2022;

Nyathi & Joseph, 2024). The persistence of outdated cascade training models, limited classroom-level mentoring and inadequate alignment between training content and daily teaching demands further exacerbate these barriers (

Nhlumayo, 2022). Teachers in resource-poor schools often rely on mobile phones, limiting their exposure to more robust digital platforms (

Flowers & Tanner, 2024;

Nyathi & Joseph, 2024).

Against this backdrop, the present study investigates the digital training needs of Grade 8–12 teachers in Mpumalanga’s Libangeni Circuit, a rural region emblematic of the broader challenges facing South African education in the digital age. Guided by the principles of Teacher Professional Development (

Desimone, 2009) and the Interconnected Model of Teacher Professional Growth (

Clarke & Hollingsworth, 2002), the study aims to map both the systemic and individual dimensions of professional learning in digitally evolving classrooms. This dual-theoretical lens enables a nuanced understanding of how institutional provision interacts with teachers’ beliefs, practices, and aspirations.

Ultimately, this study seeks to inform more inclusive, responsive, and sustainable digital training models by centring teachers’ voices and surfacing the specific supports they identify as necessary for digital integration. It contributes to the growing body of research advocating for locally grounded interventions that bridge the gap between national digital education policy and classroom realities in underserved contexts. This study emerges from engaged scholarship in which the Department of Mathematics Education collaborates with educators in the Libangeni Circuit. The survey formed part of an ongoing partnership to identify teachers’ digital training needs, with the explicit aim of designing targeted intervention strategies to empower Grade 8–12 teachers in the circuit. Framing the work within this collaborative endeavour underscores the study’s applied relevance and its contribution to sustainable professional development pathways. Comparative longitudinal work in Serbia also showed how the pandemic accelerated digital competence gains, though sustained support remained essential (

Ivanov et al., 2025).

Therefore, this study sought to answer the following research questions, which are framed by the dual-theoretical lens which links institutional provision with teachers’ beliefs, practices, and confidence.

RQ1: What are the digital training needs of Grade 8–12 teachers in the rural Libangeni Circuit?

RQ2: What levels of digital tool proficiency do these teachers currently report?

RQ3: What forms of institutional support do teachers identify as essential for effective digital integration in their classrooms?

These research questions were shaped by the study’s dual-theoretical framing: Desimone’s Teacher Professional Development framework guided the focus on institutional provision and system-level training needs (RQ1 and RQ3), while Clarke and Hollingsworth’s Interconnected Model of Teacher Professional Growth informed the exploration of teachers’ beliefs, practices, and self-efficacy (RQ2 and RQ3).

Despite the increasing prioritisation of digital education, rural teachers’ training needs remain under-examined in South Africa. Much of the existing research has focused on urban contexts or broad measures of digital readiness (

Wade & Mestry, 2021;

Flowers & Tanner, 2024), leaving rural realities insufficiently understood. Recent studies highlight that rural teachers often face fragmented, short-term professional development initiatives that frequently fail to translate into sustained classroom practice (

Soekamto et al., 2022;

Xu, 2024). Other research notes persistent gendered and generational disparities in technology adoption, yet limited empirical evidence exists on how these differences shape training needs and institutional support in rural circuits (

Nyathi & Joseph, 2024;

Shambare & Simuja, 2024).

This study addresses these gaps by focusing on the Libangeni Circuit, a rural South African context where infrastructural barriers and uneven access continue to constrain meaningful digital integration. Unlike previous research that emphasises national or provincial trends, this study provides a circuit-level analysis of digital tool proficiency, training demands, and institutional support requirements. By situating the inquiry within engaged scholarship and aligning it with established frameworks of professional growth, the study contributes new empirical insights into how rural teachers articulate their own digital training needs and the context-sensitive support mechanisms they view as most urgent. In doing so, it extends the current literature by foregrounding teachers’ voices and offering practical implications for designing differentiated, embedded, and sustainable digital training models in under-resourced settings.

2. Theoretical Framework

This study adopts a dual theoretical framing combining the principles of Teacher Professional Development (TPD) and the Interconnected Model of Teacher Professional Growth (

Clarke & Hollingsworth, 2002). Together, these frameworks provide a holistic understanding of both the systemic provision of training and the personal, reflective processes through which teachers enact professional change in digitally evolving classrooms.

Desimone’s (

2009) framework, later elaborated with

Desimone and Garet (

2015), remains seminal in defining the five core features of effective professional development: content focus, active learning, coherence, duration, and collective participation. Furthermore, together, they guided the research questions on uneven competence, self-efficacy, and systemic support.

More recent scholarship continues to validate and expand these principles, emphasising sustainability, contextual responsiveness, and iterative engagement as critical elements of effective professional development (

Darling-Hammond et al., 2017;

Korsager et al., 2022). This ensures that the theoretical base of the study reflects both its foundational origins and its contemporary extensions. Complementary frameworks such as the Teachers’ Digital Competence Scale (TDiCoS) (

Ergül & Taşar, 2023) and the Digital Competence Scale for Teachers (

Gümüş & Kukul, 2023) provide validated measures that highlight proficiency across dimensions such as pedagogy, ethics, collaboration, and problem-solving. These scales reinforce the multifaceted conceptualisation of competence that underpins this study.

The TPD framework is rooted in the work of

Desimone (

2009), who identified five core features of effective professional development: content focus, active learning, coherence, duration, and collective participation. Later expanded by

Desimone and Garet (

2015), this framework positions professional development as most impactful when it is responsive to teacher needs, aligned with curriculum demands, and embedded within the school’s instructional context. TPD frameworks are particularly useful in assessing whether training opportunities provided to teachers are relevant, sustained, and institutionally supported, a critical consideration in rural schools like those in South Africa’s Libangeni Circuit, where infrastructure and resource gaps often undermine training impact (

DeMara et al., 2019;

Mokgwathi, 2025).

While TPD frameworks offer a blueprint for structuring teacher learning opportunities, they do not sufficiently explain how teachers internalise these experiences or translate them into sustained changes in practice. To address this, the study draws on the Interconnected Model of Teacher Professional Growth (IMTPG) conceptualised by

Clarke and Hollingsworth (

2002). The IMTPG theorises professional growth as a dynamic process across four interconnected domains: the Personal Domain (knowledge, beliefs and attitudes), the External Domain (professional development and resources), the Domain of Practice (classroom experimentation), and the Domain of Consequence (salient teaching outcomes). By framing change in this way, the model emphasises the interplay between individual beliefs, available resources, classroom experimentation and observable outcomes.

Change is driven through iterative cycles of reflection and enactment, meaning that the same professional learning experience may yield different outcomes depending on the teacher’s context, motivation, or beliefs. This model is particularly useful for explaining differential uptake of digital tools among teachers with varying levels of confidence, access, and institutional support.

Together, these two frameworks allow the study to explore both the structural provision of digital training (TPD) and the individualised processes by which teachers act on, resist, or transform their learning (IMTPG). This dual lens is especially important in rural, under-resourced contexts where systemic barriers intersect with teacher agency. It thus enables a more nuanced analysis of what teachers need, how they change, and under what conditions they are most likely to integrate digital tools effectively into their professional practice.

3. Literature Review

3.1. Global Context: Digital Training for Rural Teachers

The global shift toward digital education has placed renewed pressure on rural teachers to adapt to technology-mediated pedagogies. Yet, rural educators frequently lack structured access to digital training, infrastructure, and contextualised support. According to

Xu (

2024), rural teachers in developing contexts often report low digital awareness and struggle to integrate technology effectively due to limited access to devices and inadequate systemic support. Similarly,

Soekamto et al. (

2022) found that digital literacy initiatives in countries such as Indonesia and the Middle East remain fragmented, often reliant on temporary donor projects or regional policy variations. Beyond traditional PD, innovative interventions such as digital game-based Excel training have proven highly effective in strengthening teacher proficiency and engagement (

Chen & Tang, 2023).

Emerging responses include hybrid and community-based learning models.

Que and Mo (

2024) implemented a project-based training initiative in rural China that combined mentorship with structured digital tasks, which showed promise in improving both confidence and application among mathematics teachers.

Lu and Sun (

2024) further observed that online courses embedded in professional communities, such as Artificial Intelligence (AI)-enabled teaching modules, enhanced rural teachers’ motivation and digital competence by situating learning within practice-based environments. Similar findings in Uganda by

Okoed and Bileti (

2024) revealed that digital training had the highest impact when coupled with parallel improvements in infrastructure, such as power access and internet connectivity.

3.2. South African Context: Rural Teacher Challenges in Digital Integration

While international studies provide valuable insights into patterns of digital competence and barriers to adoption, these must be interpreted within the realities of the South African education system, where infrastructural disparities and systemic inequalities uniquely shape teachers’ digital practices. Against this backdrop, the following section examines the South African context in greater depth.

In South Africa, digital inequality persists as a legacy of historical and spatial disparities.

Ngoveni (

2025) highlight that rural teachers’ access to digital training is still contingent on factors such as school location, income, and individual initiative. Teachers often rely on outdated cascade models of professional development, with little space for personalised feedback or adaptation (

Nhlumayo, 2022). As a result, training does not always translate into classroom practice.

While teacher enthusiasm remains high, training opportunities are sporadic and poorly matched to rural realities.

Aluko and Ooko (

2022) argue that current training interventions tend to be urban-centric, delivered in inaccessible formats, or assume device ownership and digital fluency.

Nyathi and Joseph (

2024) support this by noting that South African rural teachers require not only technical skills but also guided pedagogical models to apply technology meaningfully in content delivery.

Generational and gender-based disparities also shape training needs. Studies indicate that older educators are often less digitally fluent, not due to resistance but owing to limited exposure, which underscores the value of scaffolded and mentoring-based approaches (

Flowers & Tanner, 2024). Younger teachers, in contrast, tend to be more adaptive to digital tools, benefiting from training that supports interactive and learner-centred applications (

Nyathi & Joseph, 2024). Gendered patterns also influence needs: female teachers, who more frequently rely on mobile devices, require mobile-responsive training, while male teachers show greater interest in data-driven tools like Excel (

Shambare & Simuja, 2024;

Wade & Mestry, 2021).

Although the South African Department of Basic Education has emphasised digital innovation post-COVID, empirical studies show a persistent gap between policy ambitions and on-the-ground implementation. Many school management teams lacked the digital competencies to prioritise teacher development in this area, further marginalising rural educators (

Wade & Mestry, 2021). The urgent need remains for capacity-building in digital leadership at both school and district levels to enable sustainable integration of digital tools in teacher training.

3.3. Towards Inclusive and Contextualised Training Models

Contemporary research increasingly calls for training models that are embedded, responsive and iterative.

Wade and Mestry (

2021) and

Nhlumayo and Chikoko (

2022) emphasise that sustainable digital integration in rural schools is impossible without ongoing support mechanisms, such as school-based mentoring, flexible scheduling and regular technical assistance. In many contexts, teachers rely on self-taught strategies because formal training structures are inadequate (

Nhlumayo & Chikoko, 2022).

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed and deepened pre-existing inequalities in teacher professional development across South Africa, particularly in rural areas. Evidence from a rural school cluster shows that Continuing Professional Teacher Development (CPTD) during the pandemic remained transmissive and top-down, with limited teacher agency, coaching, or reflective integration of digital tools (

Nhlumayo & Chikoko, 2022;

Mphahlele et al., 2024). These low-impact models failed to prepare teachers for digitally mediated teaching during crises, reinforcing the need for transformative CPTD grounded in teacher participation and contextual relevance.

Sehar and Alwi’s (

2023) findings show a strong correlation between teachers’ digital competence and their self-efficacy in designing strategies and engaging learners, while comparable evidence from physical education contexts highlights how low confidence and lack of institutional support can hinder digital integration (

Wallace et al., 2022). Furthermore, a systematic review by

Karimi and Khawaja (

2025) similarly stressed that while teachers rely on basic applications like PowerPoint, meaningful adoption of advanced tools is constrained by limited training and systemic support.

Moreover, the success of digital professional development hinges on the alignment between teacher needs and the design of training programmes. Scholars advocate for differentiated, context-sensitive approaches that accommodate diverse levels of digital competence and provide regular access to devices, school-hour training time and data (

Aluko & Ooko, 2022;

Nyathi & Joseph, 2024). Furthermore, cross-national comparisons from Spain and the USA revealed that teacher self-efficacy with digital tools depended more on training and institutional type than frequency of use alone, again pointing to systemic support as decisive (

García-Martín et al., 2023).

Similarly,

Mphahlele et al. (

2024) demonstrate that effective digital integration in distance and e-learning contexts depends on continuous external supervision that is both pedagogically and contextually responsive. Their findings highlight the importance of aligning support structures with teacher realities, a principle equally applicable in rural school settings where infrastructural limitations mirror those in remote ODeL environments. Extending this argument,

Ngoveni (

2025) argues that the rapid emergence of AI-enabled tools makes institutional support and targeted literacy development urgent priorities, particularly for educators already navigating foundational digital gaps. Evidence from the Philippines further showed that frequent use of tools such as Excel and PowerPoint correlates strongly with teacher confidence, suggesting that structured training can extend this confidence to less-used tools (

Mayantao & Tantiado, 2024). Together, these studies reinforce the case for embedded, responsive training ecosystems that address not only tool proficiency but also evolving technological landscapes.

Finally, models such as the Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge (TPACK) and Interconnected Model of Teacher Professional Growth (

Clarke & Hollingsworth, 2002) increasingly inform teacher learning pathways. As

Shambare and Simuja (

2024) note, informal digital learning remains common among rural teachers, but without formal structures, outcomes vary widely. Structured interventions that reflect both personal and institutional realities are thus essential for scalable digital transformation in rural teaching practice.

4. Methodology

4.1. Research Design

This study employed a quantitative descriptive survey design to explore the digital training needs of secondary school teachers within the Libangeni Circuit, Mpumalanga province. The design was appropriate for capturing broad patterns of digital access, tool usage, and perceived training and support needs across a varied sample. Although thematic coding was applied to open-ended responses, the study remains positioned as quantitative because the dominant data source and analytic approach were numerical survey responses. The open-ended item was intended to capture teachers’ contextual perspectives, and the coding of these responses served to support and clarify the quantitative findings rather than to establish a separate qualitative strand.

4.2. Participants and Context

Participants were drawn from schools offering Grades 8–12 across the Libangeni Circuit. The Libangeni Circuit was purposively selected because it represents one of the most underserved rural contexts in South Africa, characterised by limited infrastructure, persistent connectivity challenges, and uneven access to digital training opportunities. Selecting this site allowed the study to capture the realities of teachers who are most affected by the digital divide. All eligible teachers were invited to participate through school-level communication channels. Participants were included if they were teaching Grades 8–12, were permanently employed at schools within the Libangeni Circuit, and were responsible for integrating digital tools into their subject teaching. A total of 85 teachers responded to the online questionnaire, representing an estimated 71% response rate out of approximately 120 circuit-wide educators.

4.3. Instrumentation

Data were collected using a structured, researcher-designed questionnaire administered through Microsoft Forms. The survey consisted of 28 items in total. Section A contained 6 demographic questions (age, gender, and years of teaching experience). In addition, items on digital access (e.g., device ownership and internet connectivity) were included to contextualise teachers’ proficiency and support needs, and these were integrated into the analysis reported in

Section 5.2 and

Section 5.4. Section B comprised 12 Likert-type items measuring self-reported digital proficiency across common platforms (e.g., Excel, Google Forms, Microsoft Teams). Section C included 10 statements on training needs and institutional support, also measured on a five-point Likert scale.

Although questionnaires were the primary tool in this study, it is widely recognised that combining them with other instruments, such as interviews or classroom observations, often enhances validity through methodological triangulation (

Cohen et al., 2018;

Creswell & Creswell, 2018). In the context of this research, however, logistical and contextual constraints across multiple rural schools made additional methods impractical. To strengthen the trustworthiness of the data, the questionnaire was systematically piloted, reviewed by experts, and aligned with established theoretical frameworks. Furthermore, the interpretation of findings was corroborated by existing literature, a form of theoretical triangulation that reinforces accuracy and accountability when multi-method designs are not feasible (

McMillan & Schumacher, 2014). This approach ensured that, despite relying on a single instrument, the study produced data that were credible, valid, and analytically robust.

The survey included multiple-response questions that captured the types of digital devices used for teaching, teachers’ familiarity with and use of digital tools such as Microsoft Word, Excel and Teams, the areas where training was needed, and the institutional support required. In addition, one open-ended question asked respondents to describe the kind of institutional support they needed to integrate technology effectively into their teaching. While the present survey was researcher-designed, validated instruments such as the TDiCoS (

Ergül & Taşar, 2023) and the Digital Competence Scale for Teachers (

Gümüş & Kukul, 2023) provided conceptual guidance in identifying relevant dimensions of teacher digital competence.

The form allowed for anonymous submission and was mobile-compatible, facilitating accessibility for teachers across school sites. Microsoft Forms’ automatic visualisation features were used for preliminary data viewing, and raw data were exported to Excel and Python 3.11.5 for deeper thematic and statistical analysis.

Although the questionnaire did not undergo full psychometric validation, several steps were taken to strengthen its rigour. Items were piloted with a small group of teachers and refined for clarity, while colleagues with expertise in educational technology reviewed the instrument to ensure alignment with the study’s aims. These measures supported face and content validity, enabling the survey to capture reliable patterns of self-reported competence that are meaningful for the study’s objectives.

In addition, the questionnaire was piloted with a subset of five teachers and reviewed by two experts in digital education to enhance clarity and alignment with research aims. While no inferential statistics were conducted, internal consistency of the Likert-type scales was calculated using Cronbach’s alpha, which yielded excellent reliability (α = 0.93). Thematic coding of the open-ended responses was applied solely for contextual enrichment and not as part of a formal mixed methods design.

4.4. Procedure

A secure link to the questionnaire was distributed through circuit-level coordinators and school principals, who encouraged staff participation. The survey was accessible for one week and participation was entirely voluntary. Respondents completed the survey at their convenience using personal or school-provided devices. No incentives were offered, and no identifying information was collected.

4.5. Data Analysis

Quantitative data were analysed using descriptive statistics, focusing on frequency counts and proportional comparisons across demographic variables. Visualisations were developed using Python (matplotlib) and Microsoft Excel, including bar charts and pie charts to enhance interpretive clarity.

Responses to the open-ended question were analysed using basic thematic coding. Recurring needs such as “internet,” “laptops,” and “projectors” were identified and grouped to infer institutional support gaps. The interpretation remained descriptive and non-inferential, consistent with the quantitative scope of the study.

4.6. Ethical Considerations

The study received ethical clearance from the Research Ethics Committee of the University of South Africa (UNISA). All participants were informed of the voluntary nature of the survey and were assured of anonymity and confidentiality. No personal identifiers were collected. Participants were made aware that completion of the survey implied informed consent. In accordance with the university’s policy and the principles of the Protection of Personal Information Act (POPIA) of South Africa, all data were stored securely and used solely for academic research purposes.

5. Findings

This section presents the findings of the survey, with a specific focus on teachers’ digital training needs, their current proficiency levels, and the institutional support required to enable effective technology integration in classrooms. The analysis draws from a sample of 85 teachers across schools serving Grades 8 to 12 in the Libangeni Circuit, Mpumalanga. Given the varied demographic makeup of the respondents, including differences in age, gender, and years of teaching experience, findings are presented in a cross-thematic manner to reveal how these characteristics shape digital skill levels and influence training and support preferences.

5.1. Respondent Demographics

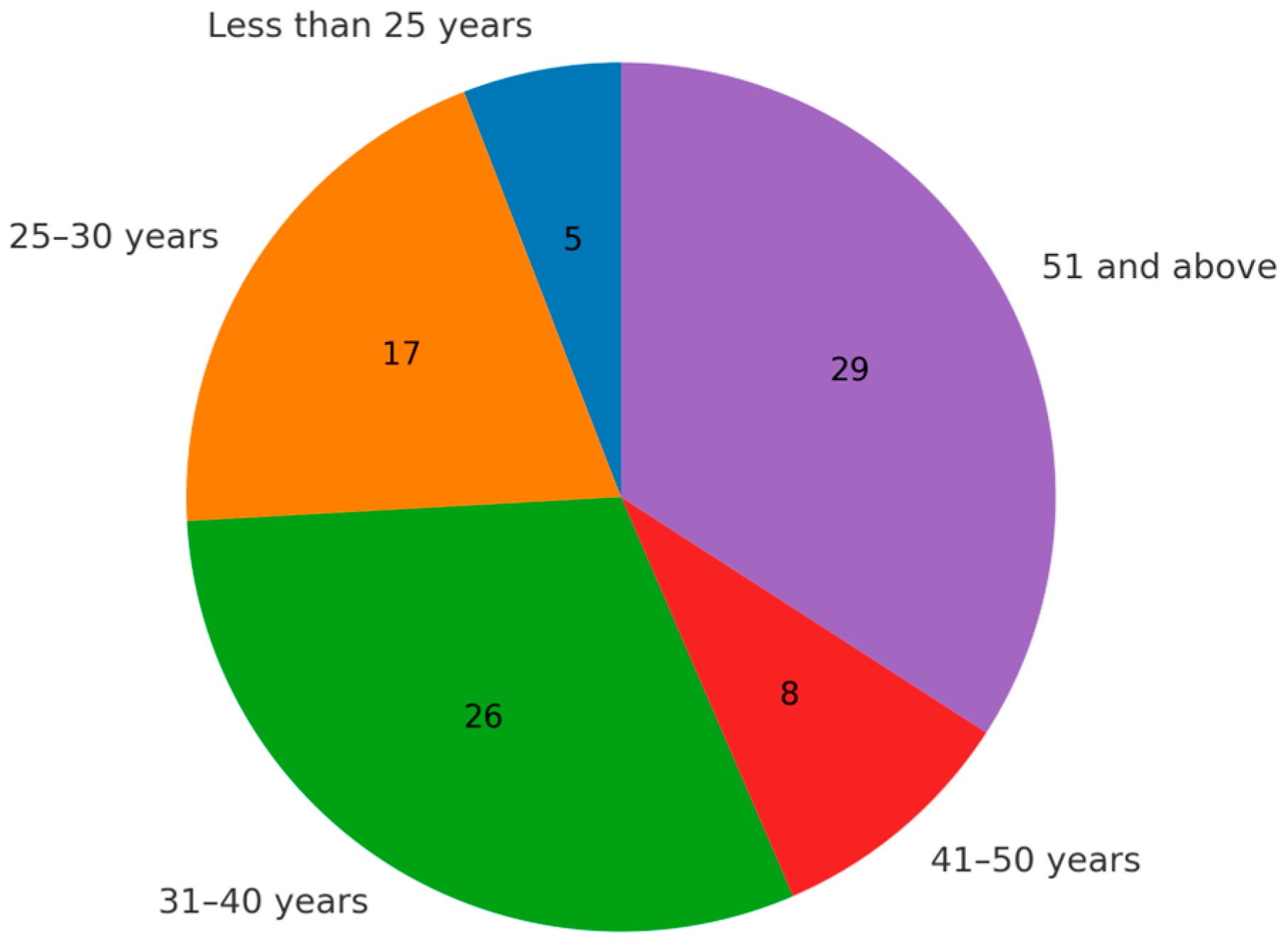

The survey population comprised teachers drawn from Grades 8–12 across eight rural schools. The demographic distribution of respondents offers critical insight into patterns emerging in later sections. The demographic profile of participants by age is shown in

Figure 1. The largest proportion of respondents fell into the 31–40 and 51 and above age brackets. This middle-aged cohort forms the majority of the workforce and plays a pivotal role in mediating curriculum change. A smaller but significant proportion (22) of teachers were 30 years or younger, suggesting that a younger generation is emerging with the potential to shape digital integration moving forward. A relatively small group of teachers (8) were in the 41–50 age category, indicating a gap in representation from this age band. Overall, the distribution reflects a workforce that is both experienced, with a substantial share nearing retirement, and replenished by younger entrants who bring new digital perspectives.

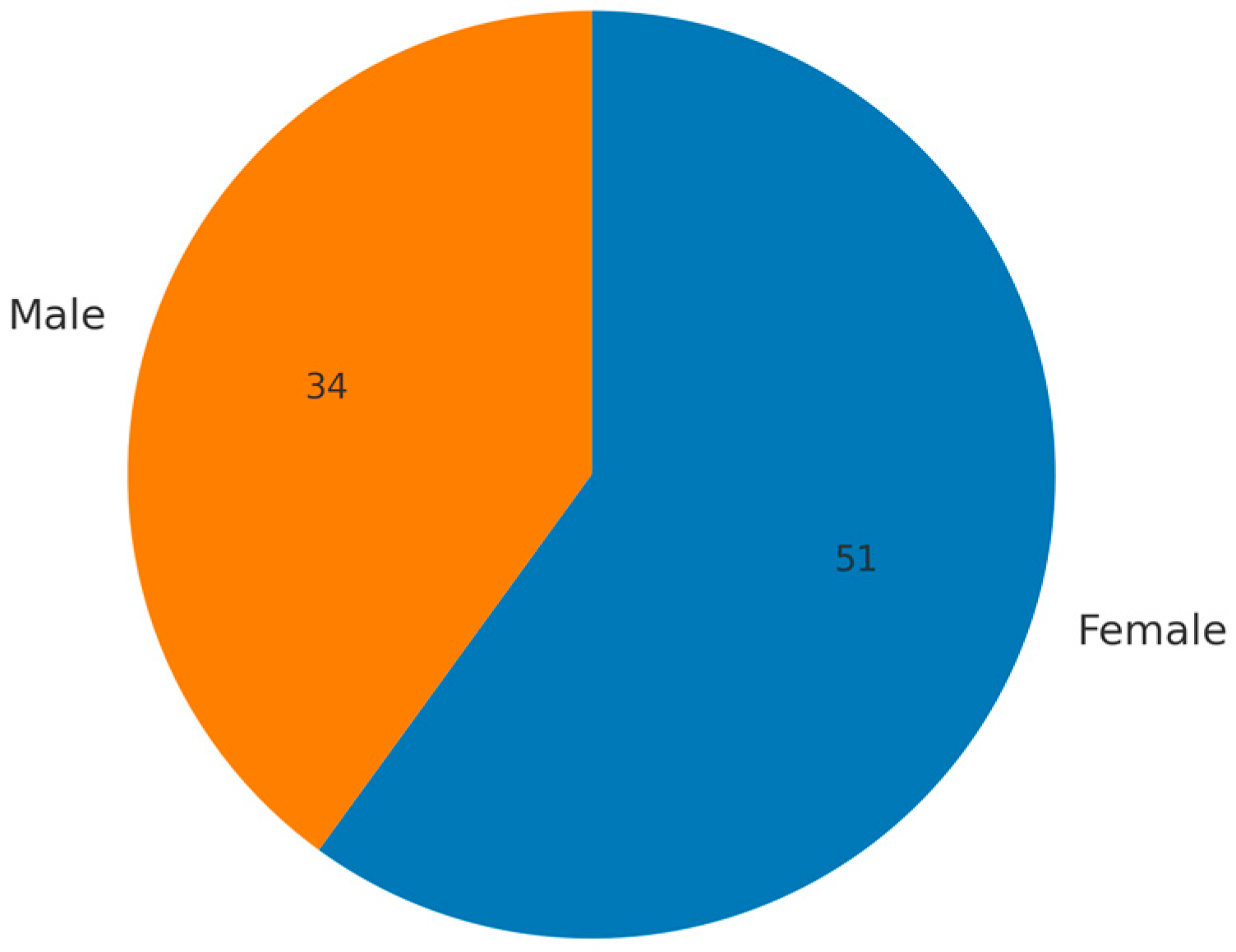

Figure 2 presents the gender distribution of participants, showing a relatively balanced profile with a slight majority of female respondents; this balance enables comparative analysis between male and female digital access patterns, particularly regarding professional development preferences and device usage.

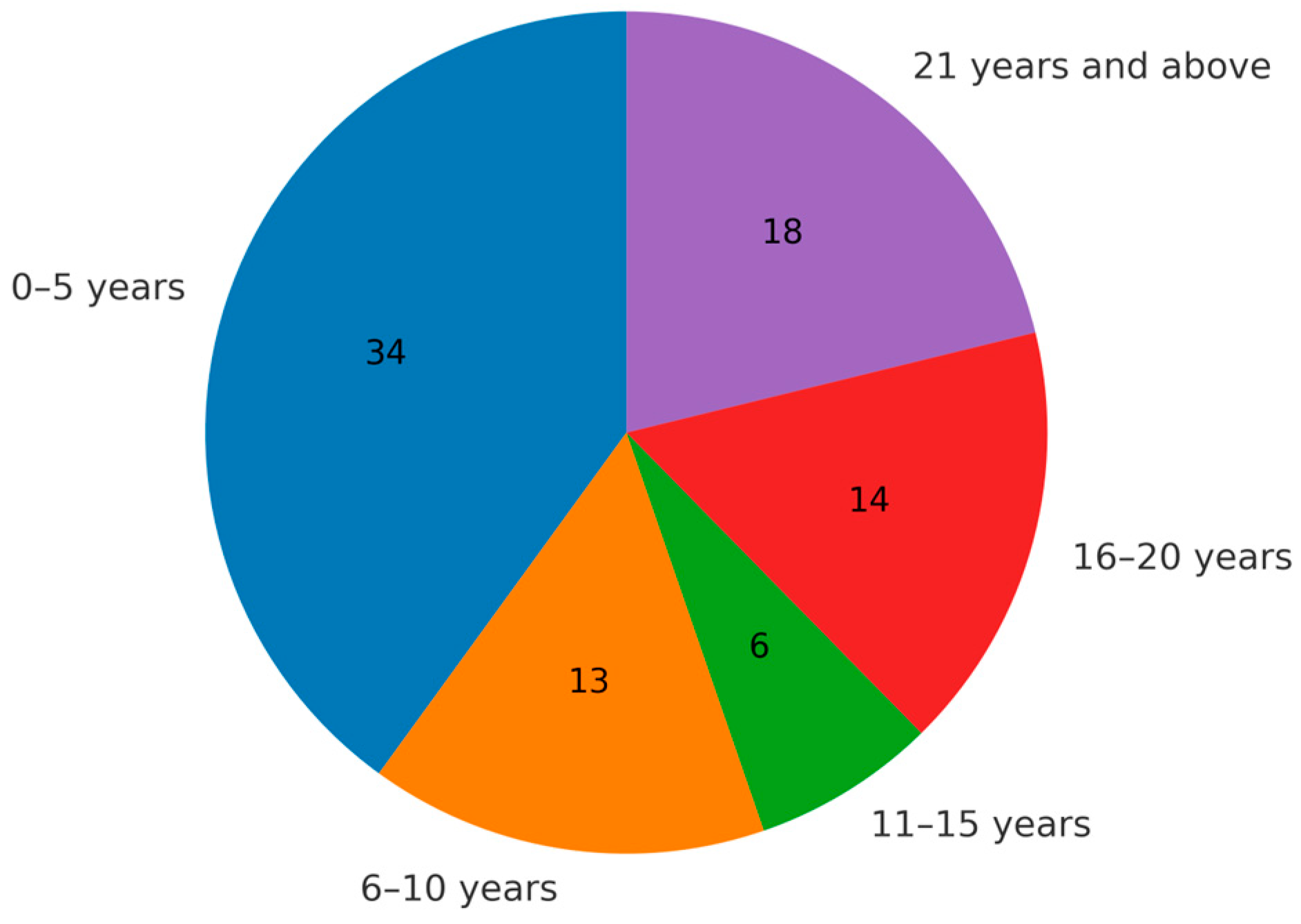

Figure 3 shows the distribution of participants according to their years of teaching experience, ranging from novice teachers with less than five years in the profession to those with over two decades of service. Experience levels varied widely, with the largest group of respondents having 0–5 years of teaching experience (34 teachers), followed by a substantial proportion with more than 21 years (18 teachers). Smaller groups fell within the 6–10 years (13 teachers), 16–20 years (14 teachers), and 11–15 years (6 teachers) categories. This distribution highlights a workforce composed of both novice teachers and highly experienced educators, enabling comparisons of how years in service relate to technological confidence and support needs. These demographic factors serve as interpretive anchors for the analysis that follows.

5.2. Digital Tool Proficiency: A Stratified Landscape

This section focuses on teachers’ self-reported proficiency in five key digital tools: Microsoft Word, Excel, PowerPoint, Teams, and Outlook. These tools were selected due to their direct relevance to teaching, communication, and classroom management tasks in a digitally integrated environment. Unlike hardware or infrastructure (e.g., smartboards, laptops), which are addressed under institutional support, these software platforms reflect competencies that can be developed through professional development and are central to daily instructional practices.

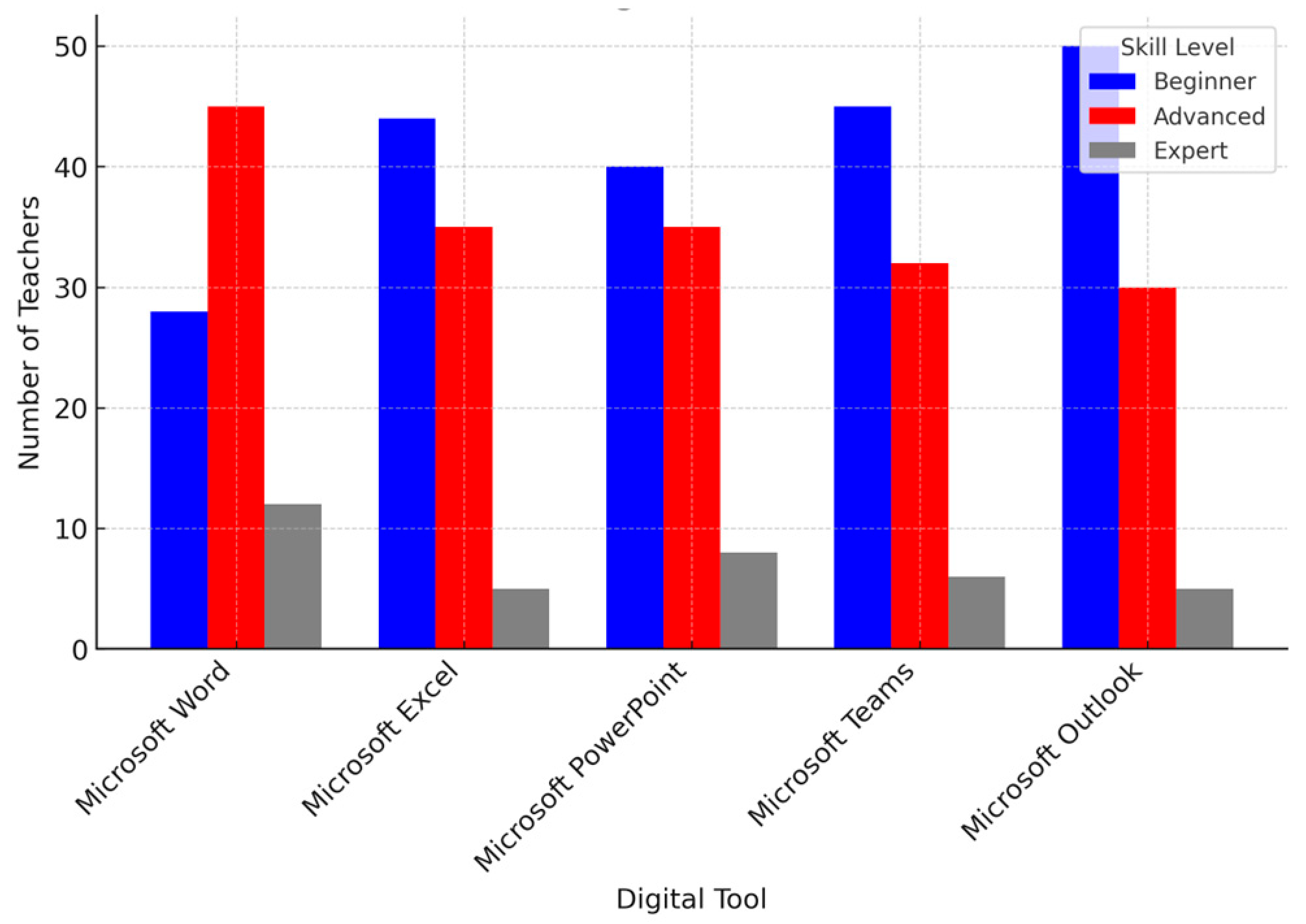

Figure 4 illustrates teachers’ self-reported proficiency in five Microsoft applications: Word, PowerPoint, Excel, Teams, and Outlook, classified into beginner, advanced, and expert levels. The y-axis represents the number of teachers in each proficiency category. Basic applications like Microsoft Word and PowerPoint were widely used, especially by teachers aged 36–45 with 11–20 years of experience. However, proficiency in tools requiring advanced digital engagement, Excel, Teams, and Outlook was significantly lower, particularly among teachers above 50 or with 25+ years of teaching. This generational divide was further mirrored by gender: female teachers were comfortable with Word and PowerPoint but underrepresented in Excel and Teams proficiency. Teachers using only smartphones (more common among female and older respondents) were more likely to lack confidence in platforms like Teams or Outlook, which are less mobile-friendly. This suggests a correlation between hardware access and skill development, reinforcing the view that digital exclusion is compounded by both resource and training gaps.

5.3. Identified Training Needs: Matching Gaps with Aspirations

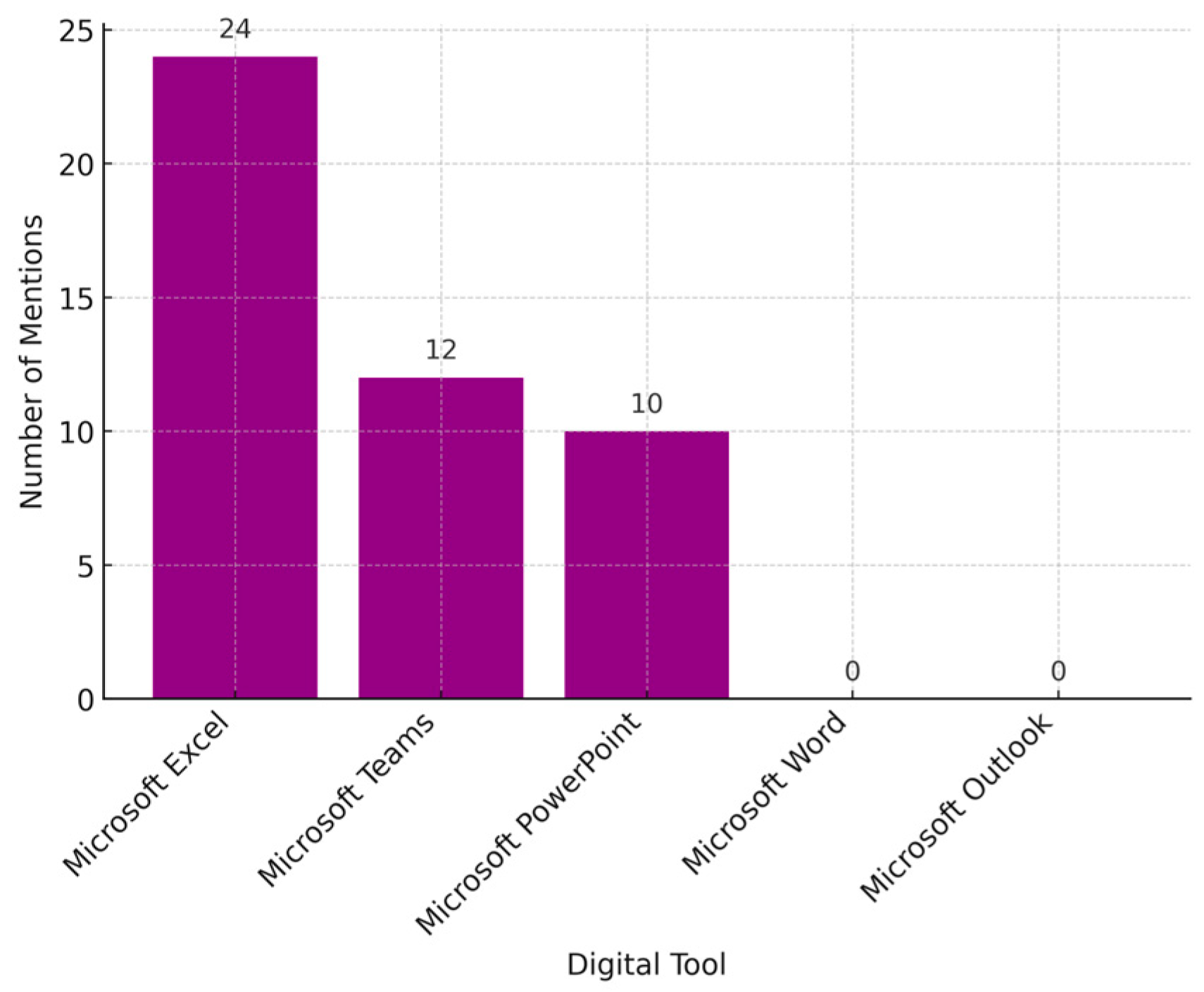

Teachers were also asked to identify the digital tools in which they would most like to receive training.

Figure 5 presents the frequency of responses, highlighting Excel, Teams, and PowerPoint as the most requested areas for professional development. Notably, the strongest demand for training arose in the very tools where confidence was weakest, suggesting a high level of reflective awareness. Teachers in the early-career group (<5 years) were eager to upskill in Teams, Google Forms, and interactive assessment platforms, tools increasingly embedded in digital pedagogy. In contrast, veteran teachers (21+ years) requested foundational support in Outlook and Teams, signalling that their main barrier is not resistance but opportunity and pace of exposure.

Gendered preferences emerged again: male teachers preferred data-driven applications (Excel, Outlook), while female teachers gravitated toward organisational and classroom tools, aligning with different pedagogical orientations and classroom management strategies. These patterns suggest that training content should be pedagogically differentiated as well as technically scaffolded.

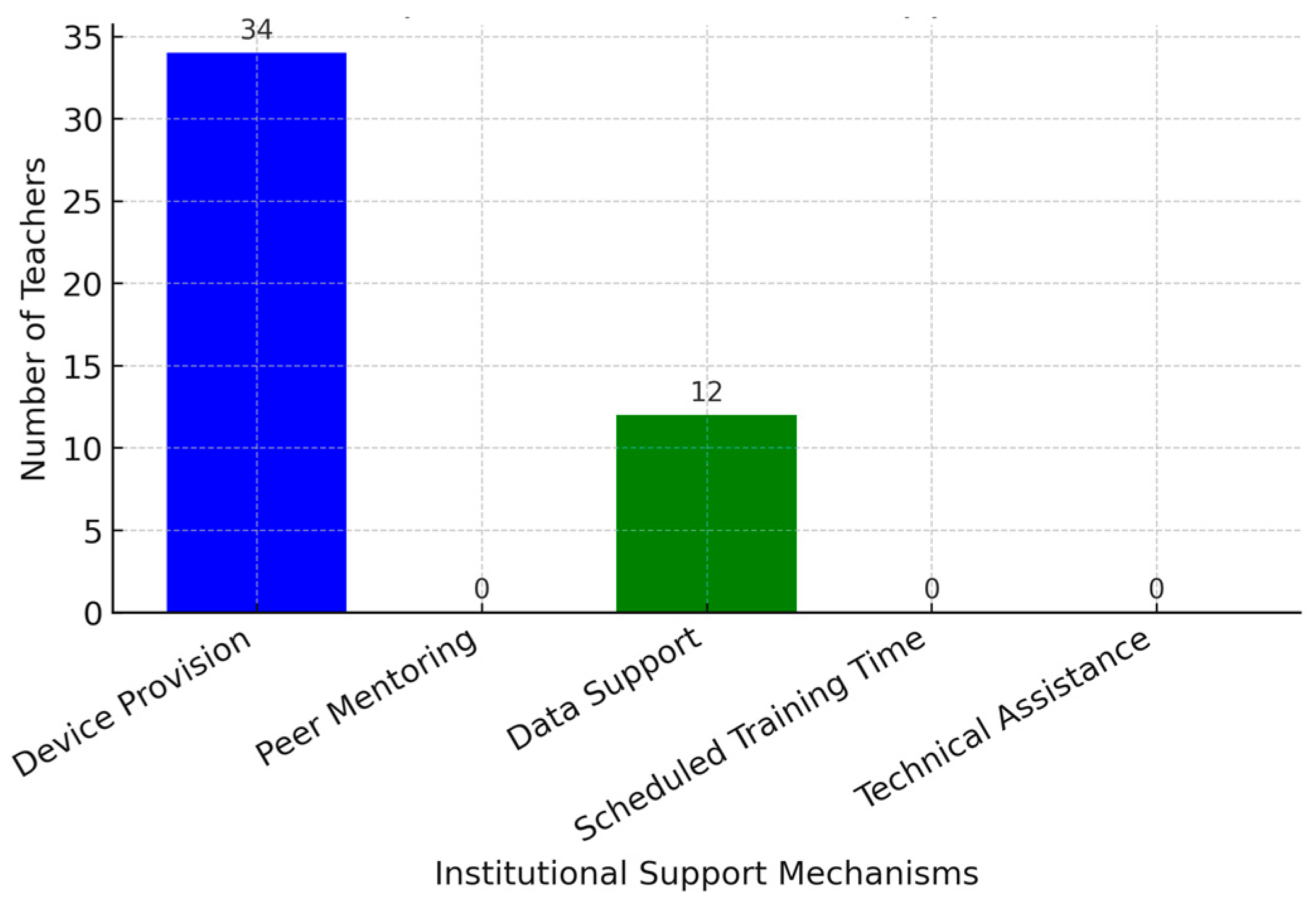

5.4. Institutional Support Needs: Bridging the Capacity Gap

Figure 6 illustrates teachers’ requested institutional support mechanisms, including device provision, peer mentoring, data support, scheduled training time, and technical assistance. The analysis of institutional support requests shows that Device Provision (e.g., laptops, projectors, smartboards) was by far the most frequently cited need, with 34 teachers identifying it as essential. Data Support (e.g., internet, Wi-Fi, routers, connectivity) followed with 12 mentions. Although no responses explicitly mentioned Peer Mentoring, Scheduled Training Time, or Technical Assistance, this may reflect the framing of the open-ended question and the clustering of responses around more general categories of institutional support. Future research could refine survey items or coding frameworks to probe such needs more directly.

Demographic patterns reveal that early-career teachers (0–5 years), often assumed to be digitally equipped, made the highest number of requests for both Device Provision (19) and Data Support (3). This challenges the “digital native” stereotype and reinforces the view that resource constraints affect all career stages. Late-career teachers (21+ years) and those over 51 also recorded notable hardware needs, reflecting a widespread dependency on institutional resourcing. Gender patterns show slightly more Data Support requests from female teachers, often linked to mobile-only access. Overall, these findings confirm that in the Libangeni Circuit, digital readiness is fundamentally contingent on equitable access to devices and reliable connectivity. Without addressing these structural gaps, even motivated and tech-aware teachers will struggle to embed digital tools meaningfully into classroom practice.

5.5. Cross-Cutting Patterns and Emerging Insights

The results demonstrate a misalignment between teacher enthusiasm and systemic provision. Despite uneven proficiency, most respondents expressed clear intentions to upskill, particularly if training were flexible, practical and linked to their subject needs. One surprising pattern was the strong motivation among older and female teachers, who are often stereotyped as technology-averse. Rather than resistance, their responses suggest an unmet demand for context-sensitive and affirming professional development. Similarly, the group with 11–20 years’ experience emerged as a critical leverage point. This group appears well-positioned to take on mentoring roles, but their responses suggest an absence of formal structures to enable this.

6. Discussion

The findings from the Libangeni Circuit confirm long-standing claims in the rural-education literature that professional development succeeds only when it knits together teachers’ emergent digital identities with concrete structural supports.

Desimone’s (

2009) framework positions coherence and active learning as the most powerful levers for sustained change; yet the teachers in this study describe workshop experiences that are episodic and concept-driven, echoing

Flowers and Tanner (

2024), who critique that South African PD often “talks technology” without “teaching with technology”. In other words, training aligns weakly with teachers’ daily pedagogical demands, violating Desimone’s coherence principle and leaving the domain of practice (

Clarke & Hollingsworth, 2002) under-populated with authentic experimentation.

The stronger proficiency observed in Word and PowerPoint compared to Excel, Teams, and Outlook is consistent with earlier studies. Applications such as Word and PowerPoint are deeply embedded in daily administrative and instructional routines, which explains their greater familiarity and use among teachers (

Abdullahi & Mohammed, 2022;

Mayantao & Tantiado, 2024). By contrast, tools like Excel and collaborative platforms demand higher levels of technical expertise and rely more heavily on institutional support, training, and infrastructure, factors often limited in under-resourced contexts (

Wallace et al., 2022;

Althubyani, 2024). This contrast highlights an important point in the scientific field: digital adoption is not merely a matter of individual willingness, but the result of interaction between teacher experience, tool accessibility, and systemic provision. As

Karimi and Khawaja (

2025) argue, teachers frequently remain anchored in basic applications unless professional development and institutional scaffolding deliberately extend their practice into more advanced digital domains.

These results align with

Mphahlele et al.’s (

2024) observation that teacher capacity-building is most effective when supported through structured, ongoing supervision rather than one-off workshops. In their work on mathematics teaching in ODeL environments, sustained engagement with teachers proved critical to converting digital skills into applied classroom strategies. Likewise,

Ngoveni (

2025) emphasises that without institutional mechanisms to anticipate and integrate emerging technologies such as AI, even motivated educators risk falling further behind in the digital adoption curve. The Libangeni findings suggest that similar principles apply in rural schooling: structural support and anticipatory training can bridge the gap between teachers’ aspirations and the fast-changing demands of educational technology.

Clarke and Hollingsworth’s Interconnected Model clarifies why this gap matters. Examination of the external domain shows that teachers receive software tutorials, but the personal domain, their beliefs about instructional relevance, remains untouched because demonstrations occur outside their curricular context. Without that personal resonance, the iterative “reflection–enactment” loop stalls; teachers return to class with isolated skills rather than integrated strategies. Studies from Uganda (

Okoed & Bileti, 2024) and Indonesia (

Soekamto et al., 2022) similarly report that rural teachers abandon new tools when they cannot see immediate curricular value, reinforcing the present finding that mere exposure is insufficient.

These findings align with

Sehar and Alwi’s (

2023) evidence that teachers’ digital competence is strongly correlated with their self-efficacy in designing instructional strategies and engaging learners. Comparable evidence from

Wallace et al. (

2022) shows that when institutional support is weak, even motivated teachers report low confidence, particularly in adopting advanced tools. Similarly,

Mayantao and Tantiado (

2024) found that frequent use of Excel and PowerPoint reinforces teacher confidence, although uptake of less common tools remains limited. In contrast,

Althubyani (

2024) reported medium competence among Saudi teachers, suggesting that while contextual barriers differ, the interplay between competence, confidence, and systemic conditions is a recurring theme across settings.

The pattern of greater confidence in Word and PowerPoint but anxiety around collaborative tools aligns with Mishra and Koehler’s TPACK model, which argues that teachers must learn not only the technology itself but also its pedagogical and content intersections. In Libangeni, training has stopped at technological competence, rarely venturing into the pedagogical layer.

Flowers and Tanner (

2024) demonstrate that when PD explicitly scaffolds these intersections, showing, for instance, how Teams can facilitate subject-specific formative assessment, uptake rises markedly. Thus, future programmes must reframe Excel or Teams not as stand-alone packages but as vehicles for curriculum delivery and learner engagement. Infrastructure constraints complicate this agenda.

Wade and Mestry (

2021) emphasise that rural South African teachers are better able to adopt digital innovations when professional development is intentionally designed around the connectivity and infrastructural realities of their schools. The Libangeni teachers’ preference for mobile-friendly applications underscores that relevance is partly technological (What tools can run on limited bandwidth?) and partly pedagogical (How can those tools enrich learning goals?). Here, Desimone’s duration characteristic becomes critical: only longitudinal mentoring allows teachers to experiment with low-bandwidth solutions, reflect on learner outcomes, and iterate practices that remain viable in resource-scarce settings.

Teacher agency emerges in the desire of mid-career educators to mentor peers. This volunteerism resembles the “nested professional communities” described by

Wade and Mestry (

2021), where informal leadership spurs diffusion of practice. Libangeni’s context suggests latent capacity for such communities, but without distal support, time allocation, data subsidies, recognition, they risk becoming what Desimone terms “invisible labour”. Embedding these communities within official PD policy would mobilise the collective participation element of Desimone’s framework, enabling teachers to co-construct knowledge in a manner attuned to rural realities.

The gendered and generational gaps reported here expand earlier findings by

Aluko and Ooko (

2022) and

Nyathi and Joseph (

2024) that women and older teachers rely disproportionately on mobile devices. The present study nuances that claim: these teachers are not technophobic; rather, their technology ecosystems are narrower, limiting opportunities for higher-level tool adoption. Clarke and Hollingsworth remind us that professional growth hinges on supportive feedback cycles; ensuring device diversity and tailored mentoring for these cohorts would multiply pathways through the model’s growth loops. In short, the findings reveal a professional development ecology that is aspirationally rich but structurally thin, leaving teacher agency to shoulder burdens that policy and infrastructure ought to bear.

This pattern echoes findings from Uganda (

Okoed & Bileti, 2024) and Indonesia (

Soekamto et al., 2022), where teachers reported high motivation but limited uptake due to infrastructure and lack of contextualised training. These cross-national comparisons reinforce the importance of designing PD that aligns with lived realities. Moreover, the assumption that younger teachers are inherently more capable is challenged by the findings: the high demand for device and data support among early-career teachers supports critiques of the ‘digital native’ narrative (

Kirschner & De Bruyckere, 2017), which oversimplifies the relationship between age and digital competence.

In addition, the pattern that early-career teachers recorded the highest requests for device provision and data support challenges the assumption that younger teachers require less institutional support. Rather than reflecting generational competence, this points to structural barriers such as device access and data affordability. This interpretation aligns with critiques of the ‘digital native’ narrative, which argue that age alone does not determine digital competence and that opportunity and systemic provision are decisive (

Kirschner & De Bruyckere, 2017).

This study makes a distinct contribution to the field of digital competence research by illustrating how disparities in tool proficiency emerge within a South African rural context. Whereas earlier studies have reported general barriers such as lack of infrastructure, workload, and insufficient training (

Wallace et al., 2022;

Althubyani, 2024), the present findings extend this knowledge by demonstrating how these barriers manifest in uneven adoption across specific Microsoft applications. The stronger reliance on Word and PowerPoint, contrasted with weaker engagement in Excel, Teams, and Outlook, provides empirical evidence of how competence is shaped by familiarity, accessibility, and institutional support. Scientifically, the study advances understanding of the interaction between competence, confidence, and systemic provision (

Sehar & Alwi, 2023;

Karimi & Khawaja, 2025). In educational practice, the findings provide a foundation for designing context-sensitive professional development programmes that can help teachers move beyond routine tool use towards more advanced and collaborative digital practices, thereby strengthening equitable technology integration in teaching and learning.

7. Conclusions

Teachers reported higher proficiency in widely used applications such as Word and PowerPoint, reflecting their routine integration into daily teaching and administrative work, while confidence and competence were notably weaker in Excel, Teams, and Outlook, which require advanced technical engagement. These uneven patterns indicate that teachers’ digital competence is shaped not only by individual familiarity but also by access to infrastructure, training opportunities, and institutional support. Overall, the findings reveal that digital adoption follows a stratified trajectory where basic tools are mastered, but progression to more complex or collaborative applications remains limited, underscoring the need for targeted interventions that build both competence and confidence across the full spectrum of digital tools.

8. Limitations

Despite yielding valuable insights into the digital training needs of rural teachers, this study is subject to several limitations. Firstly, the reliance on self-reported data introduces the possibility of response bias, as teachers’ perceived proficiency and needs may not accurately reflect their actual digital competencies. Secondly, the findings are contextually bound to the Libangeni Circuit and cannot be generalised to all rural districts or the broader national teacher population. Additionally, the study’s cross-sectional design captures a single moment in time and does not allow for the observation of longitudinal growth or the impact of training interventions over time. Lastly, while the survey instrument was systematically developed and piloted, it lacked item-level validation against established digital competency frameworks, which may limit the precision of inferences drawn regarding specific skills.

While these constraints limit the generalisability of findings to all rural districts, the study nevertheless offers transferable principles. Training should be designed to build progressively on existing competence while responding to teachers’ self-identified needs; motivation to learn is evident across demographic groups, challenging common stereotypes; and digital professional development is most impactful when combined with improvements in infrastructure, particularly device provision and affordable connectivity. These principles can inform professional development and policy in other under-resourced educational settings.

Despite these limitations, the findings offer transferable principles relevant to other under-resourced contexts. These include the value of progressive, scaffolded training aligned with teachers’ existing competencies; the persistence of digital motivation across age and gender groups; and the critical importance of synchronising PD design with infrastructural realities. Future work should triangulate survey data with interviews or classroom observations to capture the complexity of practice more fully.

Finally, the study relied solely on survey data, which, while useful for mapping broad patterns, does not capture the full complexity of teachers’ digital practices. Future research should therefore employ a sequential explanatory design that supplements the survey with interviews, classroom observations, and document analysis. This triangulation would enrich interpretation, mitigate the risks of bias associated with self-reports, and provide deeper insight into the mechanisms by which training and infrastructure shape digital competence.

9. Recommendations

In response to the findings, a set of evidence-based recommendations is proposed to support more equitable and sustainable digital teacher development in rural settings.

For Teacher Development Programmes, the design of tiered training modules is strongly recommended, beginning with basic digital fluency and progressively introducing pedagogical integration strategies. These programmes should be explicitly contextualised to reflect rural teaching conditions, including adaptations for mobile-based environments where device access is constrained. Furthermore, schools could benefit from a structured mentorship approach whereby mid-career teachers, particularly those with 11–20 years of experience, are capacitated to serve as peer mentors who facilitate sustained learning within school communities.

For Schools and District Officials, strategic steps should include the integration of protected training time within teachers’ existing timetables to promote active engagement without adding to their workload. Investment in essential digital infrastructure, such as smartboards, laptops, projectors, and subsidised mobile data, must be prioritised to bridge the current access gap. Additionally, circuit-based technical support personnel should be deployed to offer ongoing, on-demand assistance in addressing hardware and software challenges, thereby reducing teacher frustration and ensuring continuity in digital uptake.

For Policy and National Stakeholders, the study advocates for a shift away from cascade models of professional development toward more continuous, differentiated CPD platforms. These platforms should be flexible, context-aware, and aligned with teachers’ evolving digital needs. Moreover, policies aimed at promoting digital inclusion should incorporate mechanisms to recognise and incentivise schools that demonstrate innovation and effectiveness in integrating technology into their teaching and learning environments.

This study extends the practical application of the TPD and IMTPG frameworks in low-resource educational settings. The findings demonstrate that professional growth is most likely to occur where external support intersects with teacher motivation and reflective engagement. Future research should consider longitudinal studies that track the impact of training interventions and explore the role of teacher identity and school culture in digital integration.

Practically, the study confirms that without sustained infrastructural investment and pedagogically coherent training models, digital equity remains aspirational in rural South African schools. Theoretically, it affirms the value of using dual frameworks to account for both systemic provision and personal enactment in understanding professional learning.

Future Research Directions: Future studies could adopt longitudinal designs to track how teachers’ digital competence evolves over time, particularly in relation to ongoing professional development and systemic support. Expanding the sample across different provinces and school contexts would allow for broader generalisation and comparative analysis. Further research could also explore how specific interventions, such as targeted training in advanced applications like Excel and Teams, affect both competence and confidence. In addition, qualitative approaches such as classroom observations and interviews could provide deeper insights into how teachers integrate digital tools into pedagogy. Finally, future studies might examine the relationship between teacher digital competence and learner outcomes, thereby linking digital proficiency more directly to educational quality and equity.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.A.N., L.M.M., R.V.M., R.M.T., E.M.P., and G.T.M.; methodology, M.A.N., L.M.M., R.V.M., R.M.T., E.M.P., and G.T.M.; writing, original draft preparation, M.A.N.; data collection, L.M.M., R.V.M., R.M.T., and E.M.P.; writing, review and editing, L.M.M., R.V.M., R.M.T., E.M.P., and G.T.M.; funding acquisition, G.T.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the University of South Africa, project CN4800. The University of South Africa also provided financial support for the article processing charges.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and formed part of the engaged scholarship project CN4800 within the Department of Mathematics Education, University of South Africa. Ethical clearance for the project was granted by the University of South Africa Research Ethics Committee (90031113/09/AM, 2023-04-12).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available to protect the privacy and confidentiality of participants.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the use of artificial intelligence tools for language editing during the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Abdullahi, K. M., & Mohammed, M. T. (2022). Teachers’ perceptions of the impact of Microsoft learning tools in teaching of science in the FCT-senior secondary schools, Nigeria. International Journal of Arts, Sciences and Education, 3(1), 98–106. [Google Scholar]

- Althubyani, A. R. (2024). Digital competence of teachers and the factors affecting their competence level: A nationwide mixed-methods study. Sustainability, 16(7), 2796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aluko, F. R., & Ooko, M. A. (2022). Enhancing the digital literacy experience of teachers to bolster learning in the 21st century. Journal of Learning for Development, 9(3), 420–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M. Y., & Tang, J. T. (2023). Developing a digital game for Excel skills learning in higher education: A comparative study analyzing differences in learning between digital games and textbook learning. Education and Information Technologies, 28(4), 4143–4172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, D., & Hollingsworth, H. (2002). Elaborating a model of teacher professional growth. Teaching and Teacher Education, 18(8), 947–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education (8th ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Darling-Hammond, L., Hyler, M. E., & Gardner, M. (2017). Effective teacher professional development. Learning Policy Institute. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMara, R. F., Tian, T., & Howard, W. (2019). Engineering assessment strata: A layered approach to evaluation spanning Bloom’s taxonomy of learning. Education and Information Technologies, 24(2), 1147–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desimone, L. M. (2009). Improving impact studies of teachers’ professional development: Toward better conceptualizations and measures. Educational Researcher, 38(3), 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desimone, L. M., & Garet, M. S. (2015). Best practices in teachers’ professional development in the United States. Psychology, Society, & Education, 7(3), 252–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ergül, D. Y., & Taşar, M. F. (2023). Development and validation of the teachers’ digital competence scale (TDiCoS). Journal of Learning and Teaching in Digital Age, 8(1), 148–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flowers, B., & Tanner, M. (2024). Exploring the digital readiness of underprivileged secondary schools in South Africa. In Implications of information and digital technologies for development (Vol. 708, pp. 328–341). IFIP advances in information and communication technology. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Martín, J., Rico, R., & García-Martín, S. (2023). The perceived self-efficacy of teachers in the use of digital tools during the COVID-19 pandemic: A comparative study between Spain and the United States. Behavioral Sciences, 13(3), 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gümüş, M. M., & Kukul, V. (2023). Developing a digital competence scale for teachers: Validity and reliability study. Education and Information Technologies, 28(3), 2747–2765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanov, A., Radonjić, A., Stošić, L., Krčadinac, O., Đokić, D. B., & Đokić, V. (2025). Teachers’ digital competencies before, during, and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability, 17(5), 2309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, H., & Khawaja, S. (2025). Exploring digital competence among higher education teachers: A systematic review. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 24(1), 199–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirschner, P. A., & De Bruyckere, P. (2017). The myths of the digital native and the multitasker. Teaching and Teacher Education, 67, 135–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korsager, M., Reitan, B., Dahl, M. G., Skår, A. R., & Frøyland, M. (2022). The art of designing a professional development programme for teachers. Professional Development in Education, 50(6), 1286–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y., & Sun, Z. (2024). AI-enabled education: Innovative design and practice of online training for rural teachers. In Proceedings of the 2024 10th International Conference on Frontiers of Educational Technologies (ICFET ‘24) (pp. 60–66). Association for Computing Machinery. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayantao, R., & Tantiado, R. C. (2024). Teachers’ utilization of digital tools and confidence in technology. International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Analysis, 7(5), 1945–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, J. H., & Schumacher, S. (2014). Research in education: Evidence-based inquiry (7th ed.). Pearson Higher Ed. [Google Scholar]

- Mokgwathi, M. S. (2025). Investment in mathematics education and curriculum reform in South Africa: Addressing inequities and bridging the achievement gap. In Diversity, equity, and inclusion for mathematics and science education: Cases and perspectives (pp. 189–232). IGI Global Scientific Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mphahlele, R. S., Ngoveni, M. A., & Mphuthi, G. T. (2024). Enhancing mathematics teaching in open distance and e-learning: Effective external supervision strategies. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 23(12), 216–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngoveni, M. A. (2025). Bridging the AI knowledge gap: The urgent need for AI literacy and institutional support. The International Journal of Technologies in Learning, 32(2), 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhlumayo, B. S. (2022). The implementation of school-based teacher professional development in a selected South African rural context: A need for change to deal with crises. E-Journal of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences, 3(11), 51–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nhlumayo, B. S., & Chikoko, V. (2022). Continuing professional teacher development (CPTD) in South Africa in the time of COVID-19: Evidence from a school cluster in a rural context. Alternation Interdisciplinary Journal for the Study of the Arts and Humanities in Southern Africa, 29, 63–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyathi, T., & Joseph, R. M. (2024). Empowering South African educators: Navigating the challenges of digital teaching and learning competencies. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 22, e1–e10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okoed, M., & Bileti, E. A. (2024). Digital literacy training: Its impact on teachers in Busoga region, Eastern Uganda. International Journal of Recent Educational Research, 5(3), 612–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Que, X., & Mo, X. (2024, November 23–25). Construction of learning community for rural math teachers and normal school students based on digital literacy enhancement: Value, features, and pathways. 2024 IEEE First International Conference on Data Intelligence and Innovative Application (DIIA) (pp. 1–4), Nanning, China. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehar, S., & Alwi, S. K. K. (2023). Correlation between teachers’ digital competency and their self-efficacy in managing online classes. Pakistan Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 11(2), 2196–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shambare, B., & Simuja, C. (2024). Unveiling the TPACK pathways: Technology integration and pedagogical evolution in rural South African schools. Computers and Education Open, 7, 100206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soekamto, H., Nikolaeva, I., Abbood, A. A. A., Grachev, D., Kosov, M., Yumashev, A., Kostyrin, E., Lazareva, N., Kvitkovskaja, A., & Nikitina, N. (2022). Professional development of rural teachers based on digital literacy. Emerging Science Journal, 6(6), 1525–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, J., & Mestry, R. (2021). The perceptions and experiences of school management teams and teachers regarding continuing professional development of teachers in digital literacy amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. Alternation, 28(1), 338–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallace, J., Scanlon, D., & Calderón, A. (2022). Digital technology and teacher digital competency in physical education: A holistic view of teacher and student perspectives. Curriculum Studies in Health and Physical Education, 14(3), 271–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y. (2024). The value implication and path discussion of rural teacher’s digital literacy under the background of digital empowerment. Journal of Higher Vocational Education, 1(2), 73–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).