1. Introduction

Engineering education is at a pivotal moment, requiring approaches that extend beyond technical expertise to encompass the holistic well-being of students who will become tomorrow’s problem-solvers. Mental health is a critical yet often overlooked aspect of this transformation. Not only can mental health affect engineering students during their education, but a mentally healthy engineering workforce is more capable of innovating responsibly, adapting to rapid technological change, and contributing to inclusive and ethical global solutions. Indeed, employee mental health has been empirically linked to higher job performance through enhanced work engagement and innovative behavior (

Lu et al., 2022), while poor mental health has been associated with productivity losses via absenteeism and presenteeism (i.e., showing up at the workplace despite an illness) across sectors (

de Oliveira et al., 2023). Despite this, engineering students have consistently reported high rates of mental health concerns (

Danowitz & Beddoes, 2022), and evidence from a national study indicates that distressed undergraduate engineering students are less likely to seek professional help than their peers in other majors, even when controlling for demographic differences (

Lipson et al., 2016;

Whitwer et al., 2025a). Untreated mental health concerns can become more severe over time (

Barrett et al., 2008;

Wang et al., 2007), undermine quality of life (

Connell et al., 2012), and threaten academic persistence and performance (

Eisenberg et al., 2009). Because professional help can alleviate these concerns and support academic success (

Barnett et al., 2021;

Mitchell et al., 2017), addressing the treatment gap (i.e., the difference between how many people need care vs. how many receive it) among undergraduate engineers is essential for rethinking engineering education in ways that promote equity, resilience, and holistic professional development.

To foster a mentally well engineering workforce that is resilient, inclusive, and effectively prepared for the challenges of the future, it is essential to understand the factors underlying the treatment gap. The Undergraduate Engineering Mental Health Help Seeking Instrument (UE-MH-HSI) was developed to identify the mechanisms and beliefs influencing engineering students’ decision to seek help (

Hammer et al., 2024b). Using this instrument to collect data from a large sample of engineering students, our interdisciplinary research team sought to answer the following research questions:

- RQ1.

How are engineering students’ mental health help-seeking attitude, perceived norm, and personal agency individually and collectively linked with their help-seeking intention?

- RQ2.

What specific beliefs most strongly predict engineering students’ mental health help-seeking intention?

Together, this will allow for identification of key intervention targets aimed at improving help seeking across the undergraduate engineering student population.

1.1. Undergraduate Engineering Student Mental Health and Help Seeking

Overall, engineering students are experiencing high rates of mental health concerns (

Whitwer et al., 2025a). Engineering has been described as a “meritocracy of difficulty” (

Stevens et al., 2007, p. 1) fostering a “culture of stress” (

Jensen & Cross, 2021, p. 372) that negatively impacts students’ mental health. This culture not only normalizes unhealthy levels of pressure, but also disproportionately burdens students from historically marginalized groups (

Cech et al., 2017;

Danowitz & Beddoes, 2022;

Sánchez-Peña & Kamal, 2023;

Vick et al., 2025), creating systemic barriers to their persistence and success. Rethinking engineering education therefore requires cultivating learning environments that affirm mental health as integral to professional development, reduce structural inequities in student experiences, and actively support and normalize help-seeking as a critical component of inclusion.

Due to the negative impacts of untreated mental illness on students’ capacity for success, it is important for distressed engineering students to seek help when they need it. However, students majoring in engineering are among the least likely to seek professional help for their mental health, even when controlling for sociodemographic factors such as gender identity, race/ethnicity, and financial stress (

Whitwer et al., 2025a). For example, in 2021–2022, 44.4% of engineering students who responded to the Healthy Minds Study reported symptoms associated with clinically significant depression or anxiety (

Whitwer et al., 2025a). However, of those nearly 2000 distressed students, only 40.4% had sought therapy/counseling in the past year, and only 38.2% had ever received a diagnosis for their condition (

Whitwer et al., 2025a). Similarly, in a study conducted in 2020, 50% of surveyed engineering students screened positive for at least one diagnosable condition, but only 16% had received a diagnosis (

Danowitz & Beddoes, 2022).

Various studies have attempted to identify the cause for this treatment gap, and several influential factors have been identified. As stated, the culture of engineering programs normalizes stress (

Jensen et al., 2023). This can manifest as an emphasis on productivity over personal well-being (

Beddoes & Danowitz, 2022;

Wright et al., 2023), and a lack of explicit support from engineering faculty can further that narrative in students’ minds (

Ban et al., 2023;

Wright et al., 2023). Additionally, engineering promotes traditionally masculine cultural values, such as emotional control and self-reliance, that have been linked to reduced help seeking (

Akpanudo et al., 2018;

McDermott et al., 2018). For example, undergraduate engineering students have indicated that they might prefer to try to solve their mental health problems on their own (

Wright et al., 2023). Stigma, both perceived and internalized, has also been identified as a barrier to seeking help among engineering students (

Sánchez-Peña et al., 2023). Other structural barriers, such as difficulty finding a mental health professional who is a good fit, have also been cited (

Beddoes & Danowitz, 2022;

Wright et al., 2023).

However, while these factors have been identified, our understanding of the extent to which they influence engineering students’ decision to seek professional help for their mental health is limited. To facilitate the comprehensive comparison of the relative importance of help-seeking factors in shaping help seeking behaviors and identify primary beliefs (the subset of beliefs that are most predictive of intention to seek help), researchers have developed the Undergraduate Engineering Mental Health Help Seeking Instrument (UE-MH-HSI;

Hammer et al., 2024b) under the framework of the Integrated Behavioral Model of Mental Health Help Seeking (IBM-HS;

Hammer et al., 2024a).

1.2. Integrated Behavioral Model of Mental Health Help Seeking (IBM-HS)

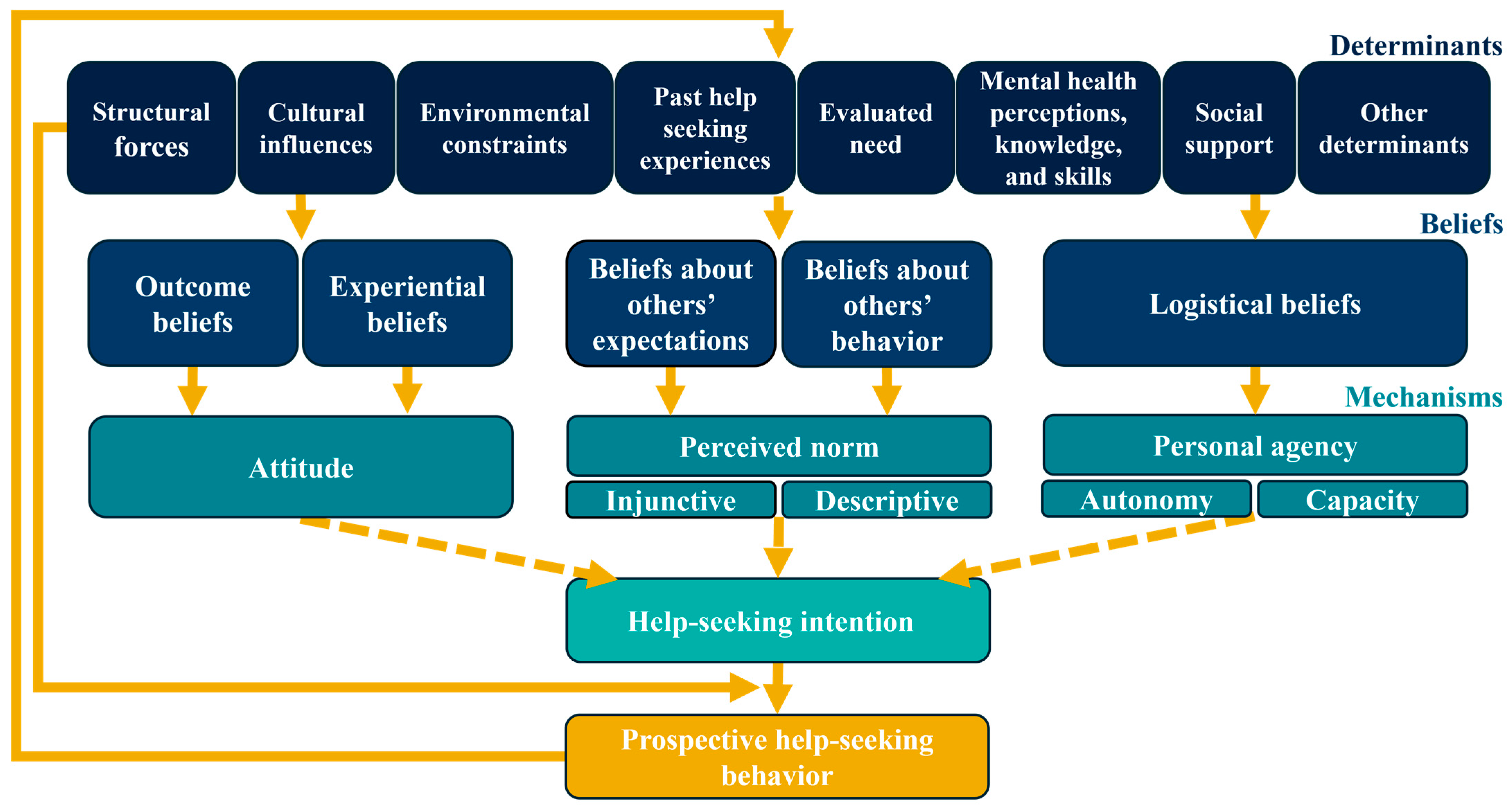

The IBM-HS is a theoretical framework for understanding the factors that influence a person’s decision to seek help for their mental health (

Figure 1;

Hammer et al., 2024a). It is a mental health help-seeking-specific adaptation of the empirically supported Integrated Behavioral Model (IBM;

Montano & Kasprzyk, 2015), part of the reasoned action tradition of theories, which include the Theory of Planned Behavior (

Ajzen, 1985) and Theory of Reasoned Action (

Fishbein & Ajzen, 2010). The reasoned action theoretical tradition is perhaps the most commonly used in the study of mental health help seeking (

Hammer et al., 2024a). In the IBM-HS, help-seeking behavior is primarily driven by help-seeking intention—a person’s self-reported readiness to exert effort to seek help from a mental health professional. Intention is itself informed by five help seeking mechanisms, which are a person’s broad, preconscious (i.e., not in immediate awareness but can be easily retrieved from memory;

Duan, 2024) perceptions about seeking help (

Hammer et al., 2024a). These mechanisms are attitude, perceived norm—injunctive, perceived norm—descriptive, personal agency—autonomy, and personal agency—capacity. Attitude is an individual’s overall evaluation of seeking help, whether positive or negative. Perceived norm is an individual’s idea about the social approval of seeking help. Injunctive perceived norm is the perception of what others would expect them to do, while descriptive perceived norm is the perception of what others would do for themselves in the same position. Personal agency is an individual’s evaluation of their ability to seek help and is composed of the mechanisms of autonomy (a person’s self-perceived personal control over seeking help), and capacity (their self-perceived confidence in their ability to do so).

These mechanisms are further influenced by mental health help-seeking beliefs (

Hammer et al., 2024a). Attitude is guided by (a) outcome beliefs, which are the anticipated results and attributes of seeking help and (b) experiential beliefs, the emotions associated with the idea of seeking help. The injunctive aspect of perceived norm is guided by beliefs about others’ expectations, that is, whether an individual believes that the people important to them would expect the individual to seek help for their mental health if needed. The descriptive aspect is influenced by beliefs about others’ behavior; whether an individual believes that the people important to them would seek help for themselves if needed. Finally, personal agency is guided by logistical beliefs—beliefs about informational, material, procedural, and performance factors that help or hinder an individual’s ability to seek help.

These beliefs are shaped by underlying help-seeking determinants such as structural forces and cultural factors (

Hammer et al., 2024a). Certain help-seeking determinants and other moderating factors can also influence a person’s efforts to act on their intention to seek help, which can impact their success in acquiring mental health care. Finally, the experience of seeking help can reciprocally shape certain help seeking determinants and beliefs, resulting in a feedback loop.

1.3. Current Study

To improve engineering student mental health help-seeking, we need to understand the reasons why the majority (60–70% per

Whitwer et al., 2025a) of engineering students with clinically significant levels of psychological distress do not seek help from a mental health professional. Therefore, this study aimed to use the UE-MH-HSI to:

Objective 1. Determine the degree to which engineering students’ mental health help-seeking attitude, perceived norm, and personal agency are individually and collectively associated with their help-seeking intention. (RQ1)

Objective 2. Identify the primary mental health help-seeking beliefs most strongly associated with help-seeking intention. (RQ2)

This knowledge will provide higher education professionals with evidence-based targets for future interventions designed to close the mental health treatment gap for this underserved population.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Recruitment

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Kentucky. After IRB approval, survey participants were recruited from five institutions across the United States between Fall 2023 and Spring 2025. The five institutions included a public southern Historically Black College or University (HBCU), a large public southern Hispanic-serving institution (HSI #1), a large public southeastern HSI (HSI #2), a large public predominantly white institution in the southeast (PWI #1), and a large public PWI on the west coast (PWI #2). Two primary recruitment strategies were used. First, an email invitation was distributed to a mailing list of undergraduate engineering students enrolled at the five institutions. Second, students completed the survey for an assignment as part of a First Year Engineering course at PWI #1 at the beginning of Fall 2024. Additional recruitment efforts at each institution involved asking engineering course instructors to share the study information with their students and hanging posters around areas frequented by engineering students. Participants were incentivized to take the survey with a USD 5 e-gift card and some were offered entry into a raffle for the potential to win an additional e-gift card of a larger value in Fall 2023.

Participants were able to skip questions they did not wish to answer and could opt out of their responses being used for research. Cases which did not consent to participate in the study, self-reported being under 18 years old, incorrectly responded to instructed response (i.e., attention check) items, indicated when asked that we should not use their data, and/or answered fewer than 12 out of the 92 items (i.e., the first four pages of the survey, or half of the mechanism items) were deleted, resulting in a final sample size of 1903 responses. A breakdown of the sample by institution and sociodemographics can be found in

Table 1.

2.2. Survey Procedures and Measures

The Undergraduate Engineering Mental Health Help Seeking Instrument (UE-MH-HSI) was developed for the purpose of identifying beliefs predictive of intention to seek professional help for a mental health concern (

Hammer et al., 2024b). It uses various multi-item self-report scales to measure the help-seeking mechanisms and intention, referred to here as direct measures. This study used Version 2 of the UE-MH-HSI (

Whitwer et al., 2025b). A summary of the measures included in the instrument is provided in

Table 2, including the name and definition of the construct, the number of items composing the measure, and the scaling for the measure. The stem question for each belief measure is included in subsequent tables, as appropriate. Higher scores on the direct measures indicate more positive/pro-help-seeking perceptions of seeking help. Higher scores on the belief measure items indicate stronger endorsement of those specific beliefs. Note, because three of the outcomes (e.g., result in a mental health diagnosis) are evaluated differentially (as bad versus good) by members of this population, it was also necessary to include three 5-point Likert outcome evaluation items (e.g., “a mental health diagnosis would be a [bad/good] thing”) corresponding to those three outcome belief items. This permitted calculation of a weighted belief score for each of these three beliefs (i.e., the product between the belief evaluation and the outcome evaluation), which was used in the analyses in lieu of the unweighted score for those three beliefs. A planned missingness strategy was used to reduce the length of the survey. Through this strategy, participants were randomly presented 66% of the items within each intention and the direct measures. For the Fall 2023 data collection from the HBCU, HSI #1, and PWI #1, participants were presented with either the outcome belief and experiential belief measures or the items for beliefs about others’ expectations and behaviors and logistical beliefs. For Spring 2024 through Spring 2025, participants from all five institutions were randomly presented 66% of all items within each belief measure.

2.3. Data Analysis

IBM SPSS Version 29 was used for all analyses. In the retained sample, unplanned missing data on the study measures ranged from a low of 0.7% to a high of 7.3%, with an overall unplanned missing data rate for the variable set of approximately 4.6%. To impute missing values for the study measures, we used a Predictive Mean Matching (PMM) scale model with 20 iterations to create 30 imputed SPSS datasets. In addition to including all direct and belief measure items, we included dummy-coded variables for participant institution, gender identity, race/ethnicity, international status, first-generation status, and current financial stress as additional predictor variables during the PMM process. For RQ1, Pearson correlation was used to investigate the relationship between the help-seeking mechanisms and intention mean score, and multiple linear regression was used to identify their relative importance after verifying that the appropriate assumptions were met. For RQ2, Pearson correlation was used to investigate the relationships between the belief items and intention. Correlation, rather than regression, was used to get a comprehensive list of beliefs associated with intention.

3. Results

3.1. Help-Seeking Mechanisms Shaping Intention

Table 3 summarizes the correlations and regression of the help-seeking mechanisms with help-seeking intention. While all mechanisms were significantly correlated with intention, attitude and injunctive perceived norm demonstrated large effects, based on the guidelines laid out by

Cohen (

1988) for correlation coefficient effect sizes in the behavioral sciences: small (

r = 0.1), medium (

r = 0.3), and large (

r = 0.5).

After conducting the linear regression between the help-seeking mechanisms and intention, we see that all mechanisms except for personal agency—autonomy account for unique variance in intention. Notably, personal agency—autonomy also had the lowest correlation coefficient and the highest mean score of the help-seeking mechanisms. That high mean score of 4.92 out of six indicates that, on average, undergraduate engineering students “moderately” agreed with the idea that seeking help is under their personal control, and most students (82.8%) agreed with it to some extent.

3.2. Outcome Beliefs Shaping Intention

To identify primary outcome beliefs, we conducted Pearson’s correlation analyses between the outcome belief items and intention (

Table 4). The most strongly correlated positive beliefs were associated with the perceived efficacy of professional treatment. Students who believed that seeking help would have positive effects on their lives were more likely to intend to seek help. In this case, students who believed that they would receive a diagnosis and/or be given medication were more likely to intend to seek help, but only if they also believed that those would be positive outcomes. Conversely, students who believed either of those outcomes to be likely while also viewing them negatively were less likely to intend to seek help. Also relating to the efficacy of treatment, engineering students who believed that seeking help would require them to invest too much time into seeking treatment, and/or that it would be a waste of time, were less likely to intend to seek help.

Perceptions of stigma (internal and external) were also found to be negatively associated with intention, where students who indicated that seeking help would hurt their pride, be a sign of weakness, or disappoint their family were less likely to intend to seek help. Finally, believing that seeking help would go against the expectations of the engineering community or that it would make them feel like an imposter in engineering were also associated with lower intention.

On the other hand, beliefs related to students’ cultural background (e.g., seeking help would reinforce negative stereotypes about people from their cultural background, the mental health professional would not understand their cultural background) had a very small or nonsignificant effect. However, the small effects of these items could be because nearly 60% of our respondents identified as White, which may have limited the influence of these culturally relevant beliefs at the general engineering student body level.

3.3. Experiential Beliefs Shaping Intention

As shown in

Table 5 for the Pearson’s correlations of the experiential belief items with intention, all three experiential beliefs were moderately positively correlated with intention. Feeling a sense of hope, relief, and confidence at the idea of seeking help was associated with increased intention.

3.4. Beliefs About Others’ Expectations and Beliefs About Others’ Behaviors Shaping Intention

Table 6 shows the results for the Pearson’s correlations between the beliefs about others’ expectations and intention. These results show that the expectations of most people in students’ lives were important to their intention to seek help, where belief that those people would expect them to seek help if they needed it was linked to higher intention. Of particular importance to stakeholders in colleges of engineering at colleges and universities in the US, classmates, advisors, professors, and industry professionals’ opinions about seeking help all appear to be tied to engineering students’ intention to seek help.

Pearson’s correlations were conducted between the beliefs about others’ behaviors and intention (

Table 7). In short, perceptions of whether those around them would seek help are indeed connected to their own intention to seek help. Comparison of

Table 6 and

Table 7 reveals two notable patterns. First, engineering students’ perceptions of what those around them expect has a stronger relationship with engineering students’ intention to seek help than does their perception of whether those around them would themselves seek help if in distress (higher correlation coefficients). Second, on average, engineering students perceive that the people around them are more likely to expect the engineering students to seek help than to seek help themselves (higher mean score values).

3.5. Logistical Beliefs Shaping Intention

Finally, we identified the primary logistical beliefs using Pearson’s correlations with intention. These results are shown in

Table 8. Beliefs related to information and accessibility of resources, the time requirements and/or opportunity costs of seeking help, and crisis-oriented views about help-seeking were all associated with reduced intention. Factors related to academics, such as not having free time due to academic workload and prioritizing academic success over mental health, were found to negatively correlate with intention to seek help. Most logistical barriers, such as cost, scheduling difficulties, and appointment availability, were nonsignificant or showed small effects in their correlation with students’ intentions to seek help. This suggests that these factors are viewed as routine aspects of the help-seeking process, rather than major obstacles.

4. Discussion

In the context of calls to transform engineering education into a more inclusive and sustainable system, understanding the role of student mental health is essential. Mental health concerns do not affect all students equally. Students from racially minoritized, gender-expansive, and other historically excluded groups often experience compounded stressors and systemic barriers that exacerbate both mental health challenges and the stigma of seeking help. Therefore, this study used the UE-MH-HSI to (Objective 1) determine the degree to which engineering students’ mental health help-seeking attitude, perceived norm, and personal agency are individually and collectively associated with their help-seeking intention and (Objective 2) identify the primary mental health help-seeking beliefs most strongly associated with help-seeking intention. Regarding Objective 1, whereas all five mental health help-seeking mechanisms were bivariate associated with intention, the most important unique predictor of intention was attitude, followed by injunctive perceived norm, and lastly personal agency—capacity and descriptive perceived norm. In other words, engineering students’ intention was most strongly linked to whether they personally viewed seeking help as good or bad, followed by their perception that important others expected them to seek help, and finally by both their confidence in their own ability to seek help and their belief that peers would do the same when in distress. In contrast, perhaps because these students’ sense of personal control over the decision to seek help (i.e., personal agency—control) was quite high (per sample mean scores), that mechanism was not meaningfully associated with their intention to seek help. These findings indicate that attitude is the most important target to improve engineering student help seeking, while the other mechanisms are important to a lesser extent. They also highlight a critical dimension of engineering education reform: the need to address not only technical learning but also the cultural and psychological factors that enable students to thrive and persist. In this way, mental health becomes integral to building a more equitable and adaptive engineering workforce. However, the practical implications of this finding are limited, as the help-seeking mechanisms do not provide topically specific targets for future intervention. This is why assessing the relationship between specific help-seeking beliefs and intention is essential, hence the use of undergraduate engineering student-specific belief measures to address Objective 2.

Regarding Objective 2, we identified the primary mental health help-seeking beliefs that most strongly differentiate undergraduate engineering students who do not intend to seek help from those who do. Our findings revealed that students with lower intention to seek help also reported lower endorsement of key beliefs that mirror patterns documented in the broader engineering education literature. These belief patterns underscore how cultural norms within engineering shape students’ perceptions of help-seeking, highlighting an often-overlooked dimension of systemic transformation needed to foster equity and sustainability in the profession.

4.1. Outcome & Experiential Beliefs

We found that perceived efficacy of professional treatment is an important factor in engineering students’ decision to seek help for their mental health and is a key aspect of mental health literacy (

Jorm, 2012). Beliefs that seeking help would result in improved mental health symptoms, or that they would be able to find a good fit with a mental health professional were associated with increased intention to seek help. Similarly, students who believed that seeking help would require too much time investment, that they would have little free time due to their academic workload, or that they would prioritize their academic success over their mental health, were also less likely to intend to seek help. This is supported in prior literature which indicates that the perceived time requirements and the opportunity costs associated with seeking help were also an important factor in engineering students’ mental health (

Sánchez-Peña et al., 2023;

Wright et al., 2023).

We also found that students’ beliefs that seeking help would require them to be too vulnerable, that it would be a sign of weakness, or that it would result in them being negatively judged by others, were all associated with reduced help seeking. Consistent with this, stigma, both personal and external, have been identified as a source of resistance to professional help-seeking, and have significant effect on engineering students’ perceptions of mental health and help seeking (

Sánchez-Peña et al., 2023). Relatedly, experiencing positive emotions toward the prospect of seeking help was also associated with increased intention. In particular, feeling a sense of hope was a strong predictor of intending to seek help, which aligns with the psychotherapy meta-analytic literature indicating that positive client expectations about their treatment is one of the strongest predictors of improvement in talk therapy (

Wampold, 2015).

4.2. Beliefs About Others’ Expectations & Behaviors

We found that students’ perceptions of the expectations and behaviors of their engineering peers and role models are significantly associated with their intention to seek help. If engineering students think that their peers and professors would expect them to seek help, and/or that those people would seek help for themselves if they needed to, they were more likely to intend to seek help. The culture of engineering, specifically in engineering education programs, has been well documented in the effects it has on engineering students and their mental health (

Ban et al., 2023;

Beddoes & Danowitz, 2022;

Jensen et al., 2023). Engineering students have reported that they and their peers act and communicate in ways that normalize high stress in their programs and set expectations about what engineering students “should” be (

Beddoes & Danowitz, 2022;

Jensen et al., 2023). We also found that engineering students believed that important others expected them to seek help (as seen in the high mean scores for these items), yet they were less likely to believe those same people would seek help themselves. This gap extends to faculty and could indicate that students rarely see professors model help-seeking for mental health, leaving them with few role models. Consistent with this,

Busch et al. (

2024) found that the scarcity of such role models among professors limited students’ perceptions that faculty understand their struggles. In addition, engineering students have reported receiving implicit messages from their engineering professors and advisors that indicate that they might not be supportive of their mental health help seeking (

Ban et al., 2023). Therefore, engineering students might neglect their mental health due to the belief that their professors might not understand what they are going through and so would not be supportive of their help seeking. Without normalized discussions about mental health, there is little to challenge these notions (

Jensen et al., 2023;

Wright et al., 2023). Together, this results in an engineering culture that contributes to low help-seeking intention among engineering students.

4.3. Logistical Beliefs

In this study, students with low intention to seek help were more likely to endorse the beliefs that they would have little free time due to their academic workload and that they would prioritize their academic success over their mental health. Further, low intention was associated with the belief that they would only seek help when they reach a breaking point. Notably, all of these concerns have been brought up in other studies as common aspects of engineering culture that influence students’ mental health (

Jensen et al., 2023;

Wright et al., 2023). Engineering students were more likely to intend to seek help if they believed they would recognize when a concern was serious enough. This reliance on self-recognition is concerning: not only do many students anticipate delaying help-seeking until a breaking point, but they may also struggle to identify the signs of a mental health concern even once that point is reached. As a result, students may not seek help until their distress has deepened, placing them at greater risk for worsening symptoms, academic decline, and broader negative impacts on their well-being.

Finally, students who believed they would be familiar with the resources available to them, or that they would know how to find information about those resources, were more likely to intend to seek help. Concerns about knowledge of resources and how to access them have also been brought up by engineering students in previous studies (

Jensen et al., 2023;

Wright et al., 2023). As mental health literacy also includes knowledge of quality resources, the ability to provide support to others, and the ability to recognize the signs of a mental health concern (

Jorm, 2012), these findings provide additional support to the notion that engineering students with low help-seeking intention may have low mental health literacy.

5. Limitations and Future Work

This study has limitations that need to be addressed by future research. First, the sample is primarily confined to the South/Southeast, with only one West coast institution, and no representation in the Great Plains, Midwest, Pacific Northwest, or Northeast. Additionally, we only have one HBCU represented in our data, with a limited sample size compared to other institutions. A majority of the sample is taken from large PWIs, with a single institution accounting for almost 60% of the sample data. This means that the generalizability of these findings may be limited, as these bulk findings are likely most representative of the majority population. Future work will collect data from additional institutions, targeting diverse populations across a wider geographic area.

Additionally, the planned missingness strategy, while necessary to keep survey time at a minimum, resulted in a large portion of missing data for certain items and identity groups. While multiple imputation was used to maximize the amount of usable data, there was risk that the estimates among these smaller sample size groups could be pulled towards the numerical majority. In response to this, we verified that the mean scores and correlations were not significantly different between the original and imputed data, which suggests that within-group response patterns were strong enough to mitigate the influence of the majority. However, this highlights another limitation of this work, which did not control for the effects of institution, gender, race/ethnicity, etc. on the mechanisms and primary beliefs. Since we know, both from prior literature and the structure of the IBM-HS, that these sociodemographic factors impact these relationships, future work will need to control for them and implement methodology that can identify differences in the mechanisms and primary beliefs between groups.

Finally, self-selection bias is another factor limiting the potential generalizability of this study. Even though all first-year engineering students at PWI #1 took the survey as an assignment, and we paid our other participants, students who are more comfortable talking about mental health are more likely to respond and consent to use their data. This could mean that the findings are more generalizable to students who hold less stigma around the topic of mental health and mental health help seeking.

6. Implications and Conclusions

This study offers important evidence about the cultural and psychological factors shaping engineering students’ help-seeking, with implications for transforming engineering education into a more inclusive and sustainable system. The UE-MH-HSI was used to explore the relationship between intention to seek professional help for a mental health concern and the mechanisms outlined in the IBM-HS, as well as to identify primary beliefs linked with intention for a semi-national sample of undergraduate engineering students. These primary beliefs can be used to inform interventions designed to improve help seeking.

Many beliefs, such as those associated with the efficacy of treatment and treatment options, as well as students’ ability to recognize a mental health concern, indicate that mental health literacy could be an important focus of interventions. Workshops can do more than simply provide students with the locations of campus resources and the services they offer; they can also supply direct links to webpages with operating hours, appointment availability, and phone numbers, making access to care more immediate and visible. In one recent study, college students advocated for additional outreach from resources, with information shared through text-messaging and in-person events, and for schools to implement incentives for attending those events and for using campus resources (

Barr & McNamara, 2022). Large-scale interventions have also proven effective for reducing stigma (

Pescosolido et al., 2020), suggesting that similar interventions specifically developed for engineering students could be effective. However, given that short-term interventions often achieve limited impact (

Reis et al., 2022), sustained, longer-term approaches should be pursued to increase the likelihood of meaningful change (

Lai et al., 2022;

Pescosolido et al., 2020). Furthermore, as noted by a World Health Organization study, a ‘one size fits all’ approach is unlikely to be effective (

Ebert et al., 2019). Interventions should consider individual characteristics and target engineering students specifically, accounting for elements of engineering culture that influence help-seeking intention. This could be done through integration of quantitative and qualitative data from prior research studies on engineering student populations or through inclusion of anecdotes that help students to connect the training to their own experiences.

Notably, many of the primary beliefs identified in this study provide a strong incentive for rethinking engineering education to create a more inclusive culture that better prepares students to solve complex global challenges. Driving cultural change within engineering can be accomplished by normalizing discussions around mental health in engineering classrooms and promoting healthy coping mechanisms among engineering students. Consistent with prior research, our findings also highlight the critical role of professors and advisors, where students’ perceptions of their expectations and behaviors were linked with help-seeking intention. As such, it is vital for engineering faculty, staff, and administration to demonstrate explicit support for their students by implementing flexible course policies, offering accommodations such as mental health days, and modeling balanced professional practices (

Wilson & Jensen, 2023).

While many faculty rely on a “flexibility as needed” approach, this often fails to ensure equitable access to these accommodations, since students who do not feel comfortable disclosing their challenges (mental health or otherwise) may be unwilling to request support (

Wilson & Jensen, 2023). By integrating flexible course policies (e.g., assignment extensions, unexcused absences, and similar supports) directly into the syllabus, instructors can expand access to accommodations for all students, rather than limiting these benefits to those who are willing or able to request formal support. For example, a syllabus might allow students to submit late work for two out of 10 homework assignments without penalty, or take up to two unexcused absences during the semester. These built-in flexibilities can help reduce barriers related to stigma, self-advocacy, and unequal access to institutional resources. However, faculty beliefs, departmental norms, and institutional expectations can strongly influence whether such flexible practices are adopted or sustained. Future work could examine how faculty perceptions of rigor, fairness, and responsibility interact with student needs and shape the broader culture around help-seeking in engineering education.

Faculty can further serve as role models by engaging in open conversations with students about well-being strategies, setting boundaries around communication outside of work hours (and clearly communicating the rationale for these boundaries to students), and sharing information with students about their hobbies and out of work interests. Modeling these behaviors helps normalize self-care and demonstrates that success in engineering is compatible with maintaining balance and authenticity. When students see faculty practicing and valuing wellness, they are more likely to feel permission to do the same, which can counter the pervasive “always-on” culture that contributes to burnout and disengagement. These small but intentional actions signal to students that caring for one’s mental health is not a weakness but a professional strength. Such cultural changes are essential if engineering is to be reimagined as a discipline where prioritizing mental health and seeking care are viewed not as exceptions but as integral to student success and professional development.

Finally, while resources can be limited, attempts to change student beliefs are not a zero-sum game. Even weakly correlated beliefs can be targeted, especially if they share conceptual similarities with other beliefs, since interventions can address several at once. For example, a workshop focused on mental health literacy can do more than inform students of available resources and how to access them. It can also emphasize the efficacy of those resources and highlight the link between mental health and academic success, preparing students to adapt and thrive in challenging environments. When faculty are engaged in delivering this content, such efforts can also normalize conversations about mental health in the engineering classroom and encourage students to discuss struggles with one another. Additionally, because engineering students’ help-seeking intention is shaped by engineering culture, college-sponsored interventions that prioritize mental health send a powerful message that their program and the broader engineering education system value equity, inclusion, and student well-being. By intentionally addressing these interconnected beliefs and cultural factors through sustained, engineering-specific interventions, institutions can advance the transformation of engineering education into a system that not only develops technical proficiency but also fosters ethical awareness, adaptability, and resilience. In this way, promoting mental health becomes inseparable from preparing a more diverse, innovative, and socially responsible engineering workforce capable of tackling complex global challenges.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.D.W., S.A.W. and J.H.H.; Methodology, M.D.W., S.A.W., J.H.H. and B.G.; Validation, M.D.W.; Formal analysis, M.D.W.; Investigation, M.D.W.; Resources, S.A.W. and J.H.H.; Data curation, M.D.W.; Writing—original draft, M.D.W.; Writing—review and editing, M.D.W., S.A.W., J.H.H., B.G. and E.V.; Visualization, M.D.W., S.A.W., J.H.H., B.G. and E.V.; Supervision, S.A.W. and J.H.H.; Project administration, S.A.W. and J.H.H.; Funding acquisition, S.A.W. and J.H.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 2225567. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Kentucky (protocol code 79499, approved 29 September 2022; and protocol code 70818, approved 19 August 2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their gratitude to Andrew Danowitz, Pamela Dickrell, Sherri Frizell, Jerrod Henderson, and Douglass Kalika for their valuable support in participant recruitment for this study. The authors also thank Joshua Duruttya for his assistance with grant management and participant incentives. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, GPT-5) to assist in refining the writing for clarity, cohesion, and concision. The authors have thoroughly reviewed and edited all content generated with this tool and take full responsibility for the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funding sponsors had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, and in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Ajzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Akpanudo, U. M., Huff, J. L., & Godwin, A. (2018, October 3–6). Exploration of relationships between conformity to masculine social norms and demographic characteristics. 2018 IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference (FIE) (pp. 1–6), San Jose, CA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Ban, N., Mensah, L. O., Whitwer, M., Hargis, L. E., Wright, C. J., Hammer, J. H., & Wilson, S. A. (2023, June 25–28). “It’s very important to my professors… at least most of them”: How messages from engineering faculty and staff influence student beliefs around seeking help for their mental health. 2023 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition, Baltimore, MD, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Barnett, P., Arundell, L.-L., Saunders, R., Matthews, H., & Pilling, S. (2021). The efficacy of psychological interventions for the prevention and treatment of mental health disorders in university students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 280, 381–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barr, M. L., & McNamara, J. (2022). Community-based participatory research: Partnering with college students to develop a tailored, wellness-focused intervention for university campuses. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19, 16331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, M. S., Chua, W.-J., Crits-Christoph, P., Gibbons, M. B., & Thompson, D. O. N. (2008). Early withdrawal from mental health treatment: Implications for psychotherapy practice. Psychotherapy, 45(2), 247–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beddoes, K., & Danowitz, A. (2022, June 26–29). In their own words: How aspects of engineering education undermine students’ mental health. 2022 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition, Minneapolis, MN, USA. Available online: https://peer.asee.org/40378 (accessed on 1 October 2025).

- Busch, C. A., Barstow, M., Brownell, S. E., & Cooper, K. M. (2024). Why U.S. science and engineering undergraduates who struggle with mental health are left without role models. PLoS Mental Health, 1(7), e0000086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cech, E. A., Waidzunas, T. J., & Farrell, S. (2017, June 24–28). The inequality of LGBTQ students in U.S. engineering education: Report on a study of eight engineering programs. 2017 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition, Columbus, OH, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Connell, J., Brazier, J., O’Cathain, A., Lloyd-Jones, M., & Paisley, S. (2012). Quality of life of people with mental health problems: A synthesis of qualitative research. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 10, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danowitz, A., & Beddoes, K. (2022). Mental health in engineering education: Identifying population and intersectional variation. IEEE Transactions on Education, 65(3), 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, C., Saka, M., Bone, L., & Jacobs, R. (2023). The role of mental health on workplace productivity: A critical review of the literature. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy, 21(2), 167–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H. (2024). Preconscious. In Z. Kan (Ed.), The ECPH encyclopedia of psychology (p. 1121). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebert, D. D., Franke, M., Kählke, F., Küchler, A., Bruffaerts, R., Mortier, P., Karyotaki, E., Alonso, J., Cuijpers, P., Berking, M., Auerbach, R. P., Kessler, R. C., & Baumeister, H. (2019). Increasing intentions to use mental health services among university students. Results of a pilot randomized controlled trial within the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health International College Student Initiative. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 28(2), e1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, D., Golberstein, E., & Hunt, J. B. (2009). Mental health and academic success in college. The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy, 9(1), 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (2010). Predicting and changing behavior: The reasoned action approach. Psychology Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, J. H., Vogel, D. L., Grzanka, P. R., Kim, N., Keum, B. T., Adams, C., & Wilson, S. A. (2024a). The integrated behavioral model of mental health help seeking (IBM-HS): A health services utilization theory of planned behavior for accessing care. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 71(5), 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammer, J. H., Wright, C. J., Miller, M. E., & Wilson, S. A. (2024b). The Undergraduate Engineering Mental Health Help-Seeking Instrument (UE-MH-HSI): Development and validity evidence. Journal of Engineering Education, 113(4), 1198–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, K. J., & Cross, K. J. (2021). Engineering stress culture: Relationships among mental health, engineering identity, and sense of inclusion. Journal of Engineering Education, 110(2), 371–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, K. J., Mirabelli, J. F., Kunze, A. J., Romanchek, T. E., & Cross, K. J. (2023). Undergraduate student perceptions of stress and mental health in engineering culture. International Journal of STEM Education, 10(1), 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorm, A. F. (2012). Mental health literacy: Empowering the community to take action for better mental health. The American Psychologist, 67(3), 231–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, H.-J., Lien, Y.-J., Chen, K.-R., & Lin, Y.-K. (2022). The effectiveness of mental health literacy curriculum among undergraduate public health students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(9), 5269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipson, S. K., Zhou, S., Wagner, B., Beck, K., & Eisenberg, D. (2016). Major differences: Variations in undergraduate and graduate student mental health and treatment utilization across academic disciplines. Journal of College Student Psychotherapy, 30(1), 23–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X., Yu, H., & Shan, B. (2022). Relationship between employee mental health and job performance: Mediation role of innovative behavior and work engagement. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(11), 6599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDermott, R. C., Smith, P. N., Borgogna, N., Booth, N., Granato, S., & Sevig, T. D. (2018). College students’ conformity to masculine role norms and help-seeking intentions for suicidal thoughts. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 19(3), 340–351. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, C., McMillan, B., & Hagan, T. (2017). Mental health help-seeking behaviours in young adults. British Journal of General Practice, 67, 8–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montano, D. E., & Kasprzyk, D. (2015). Theory of reasoned action, theory of planned behavior, and the integrated behavioral model. Health Behavior: Theory, Research and Practice, 70(4), 231. [Google Scholar]

- Pescosolido, B. A., Perry, B. L., & Krendl, A. C. (2020). Empowering the next generation to end stigma by starting the conversation: Bring change to mind and the college toolbox project. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 59(4), 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, A. C., Saheb, R., Moyo, T., Smith, C., & Sperandei, S. (2022). The impact of mental health literacy training programs on the mental health literacy of university students: A systematic review. Prevention Science, 23(4), 648–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Peña, M. L., & Kamal, S. A. (2023, October 23–27). A comparative analysis of mental health conditions prevalence and help seeking attitudes of engineering students at two institutions in the U.S.A. 2023 World Engineering Education Forum—Global Engineering Deans Council (WEEF-GEDC) (pp. 1–9), Monterrey, Mexico. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Peña, M. L., McAlister, A. M., Ramirez, N., Samuel, D. B., Kamal, S. A., & Xu, X. (2023, June 25–28). Stigma of mental health conditions within engineering culture and its relation to help-seeking attitudes: Insights from the first year of a longitudinal study. 2023 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition, Baltimore, MD, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens, R., Amos, D., Jocuns, A., & Garrison, L. (2007, June 24–27). Engineering as lifestyle and a meritocracy of difficulty: Two pervasive beliefs among engineering students and their possible effects. 2007 Annual Conference & Exposition (p. 12.618.1), Honolulu, HI, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Vick, E., Wilson, S. A., Hammer, J. H., Whitwer, M. D., & Gentry, A. N. (2025, June 22–25). Engineering student mental health status across gender identities: Analysis of data from the healthy minds study. 2025 ASEE Annual Conference and Exposition, Montréal, QC, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Wampold, B. E. (2015). How important are the common factors in psychotherapy? An update. World Psychiatry: Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 14(3), 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P. S., Angermeyer, M., Borges, G., Bruffaerts, R., Chiu, W. T., de Girolamo, G., Fayyad, J., Gureje, O., Maria Haro, J., Huang, Y., Kessler, R. C., Kovess, V., Levinson, D., Nakane, Y., Browne, M. A. O., Ormel, J. H., Posada-Villa, J., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Alonso, J., … Uestuen, T. B. (2007). Delay and failure in treatment seeking after first onset of mental disorders in the World Health Organization’s World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry, 6(3), 177–185. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Whitwer, M. D., Wilson, S. A., Hammer, J. H., & Gomer, B. (2025a). Mental health and treatment use in undergraduate engineering students: A comparative analysis to students in other academic fields of study. Journal of Engineering Education, 114(1), e20629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitwer, M. D., Wilson, S. A., Hammer, J. H., Henderson, J. A., & Frizell, S. S. (2025b, June 22–25). Creation of an intervention-focused mental health help-seeking beliefs instrument for engineering students. 2025 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition, Montréal, QC, Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, S. A., & Jensen, K. J. (2023). Strategies to integrate wellness into the engineering classroom. Chemical Engineering Education, 57(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, C. J., Wilson, S. A., Hammer, J. H., Hargis, L. E., Miller, M. E., & Usher, E. L. (2023). Mental health in undergraduate engineering students: Identifying facilitators and barriers to seeking help. Journal of Engineering Education, 112, 963–986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).