Abstract

Higher education (HE) has become a central site where the relations between democracy, pedagogy and technology are being reshaped through algorithmic infrastructures. In this context, a specific tension becomes visible: as educational processes become intertwined with systems of classification, prediction and optimization, recognition risks becoming conditional on data legibility, while pedagogical judgement is redirected toward procedural efficiency. Against this background, this article investigates how subjectivity, recognition and pedagogical responsibility can be conceptually framed when formative encounters are mediated through pedagogical practice as well as through algorithmic operations. To address this question, it develops the DEA model (Democratic Education under Algorithmic Conditions) as a reflexive, education–theoretical heuristic grounded in educational theory, subjectivation research, democratic thought and critical data studies. The model positions education, democracy and digitalisation as interdependent fields and specifies three analytical dimensions: formative, normative and inferential. These are elaborated through relational vectors and framing structures that include societal discourses, institutional configurations, cultural imaginaries and biographical conditions. The reconstruction shows how pedagogical responsibility becomes vulnerable to displacement by optimization routines, how recognition is reorganised by regimes of data legibility and how didactic relations are reconfigured through automated feedback and recommendation systems. Rather than prescribing technical solutions, the DEA model offers a conceptual orientation for tracing how algorithmic mediation redistributes recognition, responsibility and legitimacy in HE, and for sustaining Bildung and democratic subject formation under digital conditions.

Keywords:

HE; didactics; democratic education; subjectivation; Bildung; digitalisation; algorithmic mediation 1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Context

Throughout history, political struggles have repeatedly revealed the fragility of democratic institutions and the contested role of education in sustaining them. Contemporary analyses diagnose a renewed ‘crisis of democracy’, characterised by declining institutional trust, polarised publics and shrinking spaces of civic participation (Mounk, 2018; Norris & Inglehart, 2019). Recent educational research similarly highlights how these developments affect the formative, deliberative and participatory functions of education (Biesta, 2010; Dewey, 1916; Hess & McAvoy, 2015). The interdependence of democracy and education has long been marked by tensions over legitimacy, participation and recognition. These tensions are not merely discursive but materialise in institutional infrastructures, policy regimes and epistemic orders that shape who can appear as a subject of recognition and dissent within educational contexts (Giroux, 2015; Negt, 2010).

Within this configuration, universities can be read, following Giroux’s understanding of higher education as a democratic cultural infrastructure and Negt’s conception of educational institutions as sites of public formation, as hinge institutions. In this sense, the university is an instructional organisation as well as a socio-political relay in which epistemic authority, recognition and legitimacy are negotiated. Higher education (HE) therefore occupies a structurally ambivalent position: it is simultaneously a pedagogical space of formative address, a field of civic participation and a datafied environment governed through metrics, classifications and optimisation signals. In this context, digitalisation and algorithmic infrastructures do not merely modernise existing educational processes but transform the pedagogical and institutional conditions of academic life. They shape what can be seen, measured and acted upon in educational practice. Against this horizon, the question emerges of how recognition, subjectivity and pedagogical responsibility can be conceptualised when formative encounters are mediated both through pedagogical judgement and through inferential procedures embedded in software infrastructures.

1.2. Problem Statement and Research Gap

While these implications intersect with established frameworks in digital education, they articulate a distinct theoretical perspective. Whereas models such as Community of Inquiry (Garrison et al., 2000), TPACK (Mishra & Koehler, 2006), SAMR (Puentedura, 2013) and DigCompEdu (Redecker, 2017) focus on the alignment of instructional design and competence mapping, they do not address how legibility, recognition and legitimacy are reconfigured when governance shifts from dialogical justification to algorithmic inference. Read in dialogue with Foucault’s analyses of classificatory regimes and Butler’s account of recognition as a contested performative field, algorithmic mediation is understood here not as a neutral layer of optimisation but as an inferential dispositif that preconfigures the field of possible pedagogical response. In contrast to Habermasian orientations that foreground communicative justification, algorithmic systems enact forms of pre-emptive ordering in which justification is displaced by technical legitimacy. Situated within an education–theoretical horizon, this article therefore reframes Artificial Intelligence (AI) not as an efficiency-enhancing instrument but as a mediating infrastructure that reorganises recognition, judgement and addressability in HE (Hummel et al., 2025, in press; Von Thiessen & Volz, 2023). AI is approached here not as a discrete technology but as an inferential architecture that structures visibility and governs subject positions. In parallel to AI governance debates focused on fairness, transparency and accountability (Barton & Pöppelbuß, 2022; Dignum, 2019; Donner & Hummel, in press), the DEA framework translates these values into pedagogical coordinates such as recognition, contestability, reflective autonomy and institutional responsiveness and locates them within concrete didactic relations. Rather than optimising alignment between pedagogy and technology, the framework invites diagnostic inquiry into how algorithmic mediation redistributes recognition and responsibility in HE (Galle, 2021; Ifenthaler, 2023; Pelletier et al., 2021; Williamson & Eynon, 2020).

1.3. Purpose and Research Objective

Current developments in HE cannot be reduced to curricular reform or incremental pedagogical innovation. Platformised assessment cultures, analytics-driven advising systems and data governance regimes signal a deeper structural shift in how educational legitimacy is organised. Two major constellations emerge. First, pedagogical judgement is increasingly reoriented toward optimisation logics that prioritise procedural efficiency. Second, recognition becomes tied to regimes of data legibility, which determine who is seen, classified and supported. These systems do not simply assist existing practices but alter the formative conditions of academic life. They intervene in how knowledge is encountered, how assessments are negotiated and how subjectivity becomes actionable within institutional systems. Studies on dashboards, predictive analytics and adaptive tutors show how learners are labelled, ranked and nudged based on statistical inference rather than relational judgement (Bartok et al., 2023; Knox et al., 2020; Williamson & Eynon, 2020). Amoore (2020) argues that such systems generate their own categories of recognition and governability, while Feenberg’s (1999, 2002) concept of the technical code clarifies how technologies encode assumptions about knowledge and agency. Insights from critical pedagogy and subjectivation research remind us that these processes have consequences for democratic capacities of voice, agency and recognition (Dewey, 1916; Rancière, 1991).

1.4. Research Question and Conceptual Aim

Against this background, this article investigates how recognition, subjectivity and pedagogical responsibility are reconfigured under algorithmic mediation and what conceptual resources are required to sustain Bildung and democratic formation under digital conditions. The guiding research question is: How can subjectivity, recognition, and pedagogical responsibility be conceptualised when formative encounters are mediated both by pedagogical practice and by algorithmic operations? To address this question, the article develops the DEA model as a conceptual framework that maps the asymmetries between pedagogical and algorithmic framings of education and offers a heuristic lens for analysing how these configurations intersect with democratic capacities of voice, recognition and agency.

2. Theoretical Background

Research in education, philosophy and social theory has produced a wide spectrum of approaches to understanding how subjectivity, democracy and pedagogy take shape. Building on classical didactic traditions, many contributions in general didactics have examined the relational structures of teaching and learning and the forms of responsibility that arise in asymmetrical constellations between teacher, learner and content. Subjectivation theory, by contrast, shifts attention to how individuals are positioned within institutional and discursive orders, making visible how power, recognition and agency are distributed. Education theory adds a distinctly educational perspective by stressing the formative and normative weight of encounters with knowledge, tradition and alterity.

In recent years, these established perspectives have increasingly been intersected by analyses of digitalisation and algorithmic infrastructures. Rather than replacing earlier theoretical frameworks, these approaches introduce new sites of friction by showing how classificatory and predictive systems intervene in the conditions under which recognition, responsibility and subjectivity are negotiated in HE. In current debates on AI-supported teaching and learning, as Schmohl et al. (2023) note, discussions of digital transformation oscillate between promises of personalisation and efficiency and concerns about opacity and displacement. Comparable observations can be found in Knox et al. (2020), who emphasise how digital infrastructures restructure visibility and legibility in HE, and in Feenberg (1999), who highlights how technical systems are never neutral but embed particular assumptions about agency and knowledge. From this perspective, questions of pedagogy cannot be examined in isolation from the broader educational, philosophical and democratic traditions that continue to shape their meaning. The task, therefore, is not to discard existing theories but to put them into deliberate dialogue with digital perspectives in order to clarify how education, democracy and subjectivity are being reconfigured today.1

2.1. Subjectivation and Recognition

Questions of subjectivity and recognition have long been addressed in educational theory, though with different emphases and vocabularies. Building on didactic traditions, the didactic triangle (Klafki, 1996; Terhart, 2011, 2019) and general didactics (Gudjons, 2012) conceptualise education through the relational configuration of teacher, learner and content. This framing makes clear that education is never neutral but always shaped by asymmetries of responsibility. Biesta’s (2010, 2017) distinction between qualification, socialisation and subjectification sharpens this view. By emphasising subjectification as an irreducible dimension of education, he insists that learning is not limited to acquiring competencies or reproducing norms but becomes a space in which learners appear as subjects through interpretation, dialogue and responsibility.

By contrast, subjectivation theory approaches recognition from a different angle. Foucault (1982) shows how subject positions take shape through technologies of the self that render individuals visible and governable within regimes of power and knowledge. Butler (1997), partially reorienting this perspective, stresses that recognition is never settled but constantly reiterated in performative acts. While Foucault highlights the classificatory conditions under which subjects become intelligible, Butler draws attention to the instability and contingency of recognition. Honneth (1994) intervenes at this point by grounding subjectivity in intersubjective recognition, positioning mutual acknowledgment as a condition for democratic participation and self-realisation. His focus on reciprocity responds to Foucault’s classification and Butler’s instability, yet his framework has been criticised for paying insufficient attention to the technological conditions that determine who is rendered recognisable at all. These contrasts reveal both complementarities and tensions. Foucault uncovers how power organises subject positions but offers little normative orientation. Butler makes visible the fragility of recognition but gives limited guidance for pedagogical structures. Honneth centres recognition as a condition of subjectivity but does not fully address how digital infrastructures shape legibility. Together, their differences indicate the need for an integrated perspective if subject formation in education is to be understood in its full depth (Egger, 2006, 2008).

Education theory in the sense of Bildung deepens this picture by explicitly situating subjectivation within pedagogical and normative horizons. Koller (2023) emphasises the formative encounter with alterity as a site of friction and transformation, a view that aligns with Butler’s attention to instability but anchors it in concrete pedagogical practice. Benner (2025) foregrounds Bildung’s historical and normative embeddedness, offering a corrective to Foucault’s focus on disciplinary orders by drawing attention to continuity and tradition. Von Hentig (1996) contributes an essayistic but influential perspective by describing Bildung as an orientation toward openness, judgement and responsibility throughout life, which gives it democratic weight. Biesta (2015, 2017) makes clear that subjectification must be treated as a distinct educational dimension that cannot be reduced to qualification or socialisation, thereby linking Bildung theory back to pedagogical responsibility. In their differences, these theorists illuminate complementary emphases such as alterity, tradition, openness and pedagogical irreducibility, while also revealing blind spots such as the risk of overlooking structural and technological conditions. At this point, digitalisation introduces an additional level of complexity. Algorithmic mediation renders learners legible through dashboards, recommender systems and predictive classifiers in ways that echo Foucault’s technologies of governmentality and Butler’s account of performative reiteration, while simultaneously shifting recognition in Honneth’s sense from dialogical acknowledgment to data-driven legibility. The pedagogical horizon, understood here as the normative–relational space in which recognition and responsibility take shape, becomes precarious when recognition is bound to classificatory routines that reduce opacity and negotiability. Eubanks (2018) shows how algorithmic profiling stabilises systemic inequities, while Barocas et al. (2023) demonstrate how inferential modelling narrows the scope for contextual judgement. Knox et al. (2020) add that personalisation architectures and visibility regimes restructure the conditions of legibility in HE. See also Chen et al. (2020) for an overview of data governance logics in educational platforms.

The result is a dual positioning. Learners appear as educable subjects within dialogical relations and at the same time as profiles within algorithmic infrastructures. This raises both pedagogical and democratic concerns. As Bünger and Jergus (2023) emphasise, recognition is inseparable from power and visibility. Algorithmic mediation therefore participates in regimes of intelligibility, rendering some positions visible while obscuring others. Egbringhoff et al. (2023), drawing on labour sociology and digital governance, underline that algorithmic infrastructures reorganise subject positions in ways that directly affect agency and recognition, thereby redefining the conditions under which responsibility and recognition are negotiated in HE.

2.2. Democracy and Education

Democracy and education have been theorised from multiple directions, yet what unites these approaches is the assumption that democratic life depends on formative processes. Dewey (1916) describes democracy as a mode of associated living and argues that education is its condition, since reflection, deliberation and collective inquiry are learned rather than innate. His emphasis on experience resonates with Nussbaum’s (2000, 2010) claim that democratic citizenship requires cultivated capabilities of reasoning, imagination and responsiveness to vulnerability. While Dewey foregrounds shared problem-solving, Nussbaum turns attention to the inner dispositions that make such engagement possible.

In contrast, Habermas (1981) shifts the focus toward public justification. For him, legitimacy depends on communicative rationality, where norms are justified through processes of dialogue oriented toward mutual understanding. Meanwhile, Rancière (1991) unsettles this orientation by defining democracy not as consensus but as dissensus, a moment in which unexpected voices interrupt established orders of intelligibility. His view collides with Habermas’s concern for normative stability yet complements it by insisting that democratic life requires the capacity to disrupt existing hierarchies of sense. Building on these tensions, Uljens (2023) introduces an education–theoretical inflection by conceptualising democracy as dialogical openness and self-limitation. His perspective can be read as an attempt to mediate between Dewey’s participatory horizon and Habermas’s communicative model while also leaving room for the interruptions emphasised by Rancière. Giroux (2015) adds a structural dimension by showing that educational institutions do not operate in abstract spaces but are shaped by neoliberal rationalities and technological infrastructures. Seen together, these approaches do not converge into a single definition but form a constellation of tensions. Dewey and Nussbaum stress experiential formation and capability, Habermas grounds democracy in justification, Rancière highlights interruption, Uljens foregrounds dialogical openness and Giroux draws attention to structural constraint. Their divergences are not deficiencies but resources for understanding how education is constitutive of democratic life across different dimensions. At this point, algorithmic mediation introduces a new layer to this constellation. Systems of classification and prediction risk displacing communicative justification, central to Habermas, with procedural operations that are opaque and non-negotiable. Optimisation logics suppress the disruptive moments that Rancière identifies as democratic events, while predictive pathways constrain the exploratory inquiry valued by Dewey. Personalisation architectures narrow the exposure to alterity that Nussbaum sees as crucial for imagination and empathy. Uljens’s dialogical openness becomes fragile when pedagogical interactions are pre-structured by algorithmic norms, and Giroux’s concern with structural pressures—stemming from neoliberal performance metrics and efficiency regimes—is intensified when data-driven infrastructures entrench expectations of efficiency and performance.

Insights from technology and governance research further sharpen this picture. Siemens’s (2013) framework of learning analytics and Ifenthaler’s (2023) Learning Analytics Reference Model illustrate how data practices influence pedagogical decision-making (Bartok et al., 2023; Hummel, 2021). Dignum’s (2017, 2019) work on responsible AI echoes Habermasian concerns about legitimacy and accountability but does not address the formative dimensions emphasised by Dewey or Nussbaum. Williamson and Eynon (2020) demonstrate how policy networks of educational data reconfigure governance logics, thereby empirically grounding Giroux’s critique of structural constraint. In this light, algorithmic infrastructures do not merely augment existing educational practices but recalibrate the democratic conditions of subject-formation by reshaping visibility, recognition and the terms of participation.

2.3. Toward a Heuristic Synthesis

While the existing frameworks have profoundly shaped research in digital education, their underlying orientation remains largely functional and design-based. The Community of Inquiry (Garrison et al., 2000), TPACK (Mishra & Koehler, 2006), SAMR (Puentedura, 2013) and DigCompEdu (Redecker, 2017) each provide valuable structures for aligning technology, pedagogy and content, yet they tend to conceptualise learning in terms of competence acquisition, interactional presence and measurable performance. Their pedagogical logic is instrumental and oriented toward optimisation, assuming that educational improvement follows from the systematic integration of technological affordances. This perspective has advanced instructional design but has paid little attention to the epistemic and ethical implications of digital mediation. What remains underexplored is how algorithmic infrastructures transform visibility, recognition and authority within educational relations and how this transformation affects the conditions of judgement and responsibility in teaching and learning. These frameworks illustrate one powerful orientation in contemporary educational thought. They view teaching as a process that can be enhanced through standardisation, scalability and evidence-based feedback. The assumption is that more data and better design will necessarily produce better learning. Yet this outlook risks overlooking the relational, interpretive and normative character of education itself. When learning becomes framed through metrics, dashboards and predictive models, the very meaning of pedagogical responsiveness begins to shift from interpretive understanding toward procedural efficiency. This shift reveals an epistemic blind spot that cannot be resolved through further design refinement alone.

In contrast, the traditions of Bildung and democratic education adopt a markedly different stance. Dewey (1916) understands education as a form of participatory inquiry through which individuals learn to deliberate and act together. Freire (1970) develops this idea into a pedagogy of emancipation grounded in dialogue and critical consciousness. Biesta (2015, 2017) advances the argument by insisting on subjectification as an irreducible dimension of education that cannot be captured by standards or learning outcomes. These approaches share an understanding of education as a formative and ethical process rather than a technical one. They view judgement, dialogue and responsibility as central to human growth and democratic life. However, even these humanist frameworks require reconsideration under digital conditions. As algorithmic systems increasingly participate in shaping what counts as learning, agency and legitimacy, the formative perspective that Dewey, Freire and Biesta describe becomes entangled with new forms of inference and classification. Educational recognition no longer unfolds only within human relations but is mediated by data architectures that predefine what is visible and actionable. In this sense, the democratic and education-oriented theories, while normatively rich, have not yet fully addressed how algorithmic mediation reconfigures the spaces in which recognition and responsibility take form. Viewed together, these two strands—design-oriented pragmatism and education-oriented normativity—illuminate two distinct epistemic orientations in educational theory. One privileges optimisation, alignment and measurement; the other foregrounds formation, openness and ethical encounter. Both contribute valuable insights, yet each neglects a dimension that the other foregrounds. The design frameworks provide procedural clarity but lack normative depth, while the Bildung and democracy traditions articulate ethical and formative dimensions without adequately engaging the technological infrastructures that now shape educational life. Between these orientations lies a conceptual gap: the absence of a perspective that can relate the procedural rationality of algorithmic systems to the normative rationality of pedagogy.

The DEA framework emerges from this gap. It does not reject earlier models but repositions them within a broader analytical horizon. The framework takes from design-based approaches their systematic attention to structure and process, while grounding them in the formative, normative and democratic concerns of Bildung theory. It thereby establishes a diagnostic heuristic for examining how pedagogical and algorithmic logics intersect and how recognition, legitimacy and responsibility are redistributed through this encounter. The DEA model extends the classical frameworks by shifting the analytical focus from technological alignment to epistemic diagnosis. It reframes digital education not as a question of effective integration but as a problem of how knowledge, subjectivity and democracy are reconstituted under algorithmic conditions. Through this synthesis, the framework provides conceptual tools to analyse education as a field in which optimisation and formation, prediction and responsibility, data and democracy are in constant negotiation. Across these perspectives, education does not appear as a linear process but as contingent and marked by tensions between recognition, responsibility and institutional structuring. Under digital conditions, subjectivation takes shape in moments of friction and opacity, where learners encounter otherness and are prompted to reorient themselves. Insights from labour and organisational sociology reinforce this view by showing that subject positions are not individually experienced as well as historically produced and institutionally organised (Bünger & Jergus, 2023; Egbringhoff et al., 2023). From this angle, algorithmically mediated education does not simply extend existing pedagogical practices but reorganises the conditions under which subjectivity is produced, evaluated and made actionable.

Empirical reviews of AI in education illustrate these shifts. Studies on adaptive tutoring, predictive analytics and learning dashboards show how digital infrastructures increasingly shape pedagogical conditions (Chen et al., 2020). While such accounts document technological interventions, they often leave open the deeper question of how pedagogical and algorithmic logics intersect. Pedagogical models, grounded in didactic theory and Bildung, emphasise relationality, interpretive judgement and responsibility. Algorithmic systems, in turn, operate through classification, prediction and optimisation, structuring legibility, perceptibility and addressability in ways that recalibrate what can count as recognition and response. At this point, a conceptual clarification becomes necessary. AI in this article is not approached as a technical instrument but as an inferential dispositif that structures what can be seen, measured and acted upon in educational practice. This perspective corresponds to classic analyses of the hidden curriculum (Apple, 1980; Jackson, 1968), which demonstrate that educational visibility and recognition are always mediated by implicit structures of valuation. Engel and Kerres (2023) extend this line of thought into the post-digital condition by arguing that digital infrastructures no longer operate as external tools but actively participate in processes of subjectivation by redistributing perceptibility and agency within educational environments. Through operations of classification, prediction and optimisation, algorithmic systems condition visibility and recognition, thereby redefining how pedagogical judgement can be exercised (Amoore, 2020; Feenberg, 1999; Knox et al., 2020). Rather than adding a layer to existing practices, algorithmic mediation reconfigures the epistemic conditions under which learners and educators become intelligible and governable. This clarifies why questions of democracy and Bildung cannot be addressed without engaging the logics of datafication and governance. A heuristic synthesis is therefore required to analyse the interplay of these dynamics. The following conceptual work proceeds by explicitly contrasting pedagogical and algorithmic logics as interdependent yet tension-filled dimensions of educational modelling. In this perspective, the model operates not as a reconciliatory framework but as an instrument for tracing what becomes recognisable, governable and didactically actionable under algorithmic conditions and what is rendered opaque or foreclosed in the process. This synthesis is conceptual rather than empirical and is designed to clarify how recognition, responsibility and subjectivity are being reshaped under digital governance. Algorithmic infrastructures are treated here as ambivalent: they may extend access and responsiveness while at the same time narrowing the horizon of recognition and agency.

The DEA model is developed through an education–theoretical reconstruction grounded in a Bildung perspective, rather than through empirical induction or design-oriented modelling. In this context, reconstruction refers to a conceptual practice within educational theory that seeks to make visible the normative and epistemic conditions of subject-formation under changing socio-technical environments. The model is therefore not presented as a framework for instructional optimisation but as a diagnostic heuristic that traces how recognition, judgement and legitimacy are reorganised when pedagogical relations intersect with inferential infrastructures. Drawing on subjectivation theory, democratic education and critical data studies, this education–theoretical reconstruction treats interpretive judgement, addressability and pedagogical responsibility as core reference points against which algorithmic mediation in HE can be critically examined. Rather than dissolving tensions between pedagogical and algorithmic logics, the model maintains them as epistemic friction essential to democratic-educational analysis.

3. The DEA Model: Conceptual Premises and Structuring Logics

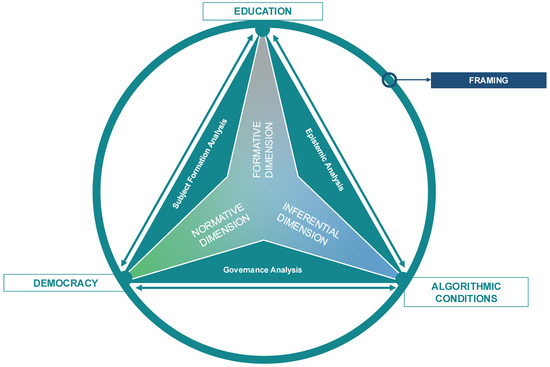

This section develops the DEA model (Democratic Education under Algorithmic Conditions) as a heuristic framework for analysing how pedagogical, democratic and algorithmic logics intersect in HE. Its orientation follows a reflective modelling practice, in the sense that educational theory is understood not merely as describing its objects but as critically interrogating the conditions under which learners are conceptualised, recognised and made governable. The model is not presented as a competence catalogue or instructional tool but as a conceptual lens for examining how recognition, responsibility and legitimacy are redistributed under digital conditions. Within this orientation, the DEA model frames HE as situated at the intersection of democracy, pedagogy and digitalisation. Rather than treating these as separate domains, it conceptualises them as relational fields in which subject formation is continuously shaped by competing claims of legitimacy, efficiency and recognition. The model delineates this field through a triangular constellation of education, democracy, and algorithmic conditions, embedded in wider socio-technical and political configurations (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The DEA Model: Democratic Education under Algorithmic Conditions.

3.1. Vertices of the Model

The DEA model positions Education, Democracy, and Digitalisation as three relational fields that structure subject formation in HE.2 These vertices do not function as separate domains but gain their meaning in relation to one another, insofar as pedagogical responsibility, democratic legitimacy and algorithmic governance intersect in concrete educational practices.

- Education refers to pedagogical and didactic processes oriented toward formation, interpretive judgement and responsibility.

- Democracy designates the normative horizon of recognition, participation and contestation that sustains collective life.

- Digitalisation refers to the infrastructural embedding of data-driven systems in HE, while algorithmic mediation names the specific logics of classification, prediction and optimisation that shape legibility and addressability, as discussed in Section 2.3.

Within this configuration, pedagogical practices are shaped not in isolation but through normative commitments to recognition as well as through the structuring effects of digital infrastructures. Digital systems are therefore understood not as neutral additions but as active elements of governance that condition how subjects become visible and accountable.3 The triangular constellation of Education, Democracy and Digitalisation can thus be read as a field of tension in which recognition, responsibility and governance are continuously renegotiated. To orient this constellation analytically, Table 1 summarises the three vertices together with guiding perspectives and analytical foci.4

Table 1.

The three dimensions of the DEA Model–Democratic Education under Algorithmic Conditions.

3.2. Analytical Dimensions

Three analytical dimensions make it possible to examine how the vertices of the model interact and how subjectivity is reconfigured under algorithmic mediation. The dimensions are conceptually distinct but relationally entangled: each foregrounds a different guiding question-formation in the formative dimension, legitimacy and address in the normative dimension, and inferential operations in the inferential dimension-while allowing overlaps at the level of relational conditions.

3.2.1. Formative Dimension

Building on Section 2.1, which framed Bildung as relational and open-ended, this dimension specifies how formative processes are reshaped under digital conditions. It does so by articulating three relational conditions:

- Locus of judgement—whether interpretive discretion remains with educators or is delegated to algorithmic routines.

- Dialogical recognition—whether learners are addressed as educable subjects or reduced to profiles.

- Temporal openness—whether detour, interruption and delay remain recognised as formative or are eliminated in the name of efficiency.

These conditions indicate core structural configurations of pedagogical responsibility. When judgement migrates into automated routines, dialogical recognition tends to contract and temporal openness is translated into acceleration imperatives. The formative dimension thus clarifies how algorithmic mediation intervenes in the temporal, relational and ethical conditions of Bildung. In institutional analysis, such dynamics become visible in assessment scripts, advising procedures and governance arrangements that either preserve spaces for pedagogical interruption or align interaction with optimisation logics.

3.2.2. Normative Dimension

Extending Section 2.2 and drawing on subjectivation theory (Butler, 1997; Foucault, 1979), this dimension examines how learners are positioned within institutional and discursive orders. Subjectivity is understood here not as a stable essence but as a function of addressability, recognition and participation. Two conditions are central:

- Negotiability of address—whether learner positions can be contested or are stabilised through classificatory routines (Butler, 1997; Fricker, 2007).

- Traceability of performance—whether recognition arises dialogically or becomes bound to data legibility regimes through machine-readable traces.

These conditions align with debates on epistemic injustice (Fricker, 2007), data colonialism (Couldry & Mejias, 2019) and algorithmic governance (Daly et al., 2019). As Barton and Pöppelbuß (2022) note, principles such as fairness, accountability and transparency are increasingly invoked in AI governance, yet their translation into pedagogical and democratic contexts remains unsettled. The educable subject risks being subordinated to the algorithmically inferred profile, thereby shifting legitimacy and agency toward data infrastructures. These shifts can be observed in how institutional procedures allocate recognition: whether appeal mechanisms exist, whether classifications can be contested and to what extent evaluative processes rely on dialogical rather than data-driven recognition.

3.2.3. Inferential Dimension

Elaborating the contrast outlined in Section 2.3, this dimension distinguishes pedagogical from algorithmic logics of modelling. Pedagogical modelling operates through relationality, interpretation and contingency, allowing for unpredictability and delay as integral to formation. Algorithmic modelling, by contrast, is structured through pattern recognition, prediction and optimisation (Ifenthaler, 2023; Knox et al., 2020; Williamson & Eynon, 2020). Their frictions manifest in three domains (see Table 2):

Table 2.

Cross-Dimensional Definitions of the DEA Model: Normative, Formative, Inferential.

- Epistemic: interpretive judgement versus statistical regularity.

- Didactic: formative detour versus linear sequencing.

- Ethical: dialogical recognition versus conditional legibility.

Inferential modelling narrows the space for contextual judgement (Barocas et al., 2023), reshaping how learners become visible and actionable in HE. These dynamics materialise in advisory dashboards and predictive flagging systems. The model distinguishes between opaque inference, such as proprietary systems, and configurable or auditable infrastructures, since degrees of transparency affect both epistemic friction and possibilities for contestation.

3.3. Relational Vectors and Governance

To make the intersections outlined above analytically visible, the DEA model introduces what it terms relational vectors. These vectors do not serve as thematic clusters but as markers of structural tension that have already emerged in Section 2, particularly around agency and dissent, epistemic legibility and institutional accountability. Situated across rather than within individual contexts, they reveal how shifts in one field modulate conditions in the others: Voice, recognition and contestation–located at the intersection of educational and democratic dynamics.

- Epistemic friction and legibility of the subject—emerging between education and digitalisation.

- Accountability, transparency and governance—operating between democracy and digitalisation.

Seen through this lens, relational vectors make visible how algorithmic mediation reconfigures pedagogical relations. When epistemic friction is minimised through classificatory normalisation, the scope for voice and contestation contracts, and accountability becomes increasingly detached from dialogical justification. In this model, governance is not understood as managerial coordination but as a normative-institutional ordering through which responsibility is distributed, legitimacy negotiated and accountability rendered visible at the intersection of pedagogy, democracy and digital infrastructures. For analytical clarity and future operationalisation, Table 3 specifies the three vectors, their definitions and their guiding diagnostic questions.

Table 3.

Analytical Axes of the DEA Model.

3.4. Framing Structures

Framing functions as a complementary analytical layer that precedes institutional governance. Rather than confining the model to procedural arrangements within HE, the concept draws attention to the broader horizons in which recognition, responsibility and legibility are interpreted before they become formalised in policy or practice. These horizons condition what can appear as pedagogically relevant, democratically legitimate or technically actionable. Within the educational vertex, biographical trajectories and dispositions influence how learners encounter expectations and recognition. Consistent with education–theoretical accounts of contingency, such experiences demonstrate that formation emerges through lived uncertainty and exceeds the inferential logics of algorithmic classification. In this respect, framing draws attention to the epistemic and cultural conditions under which pedagogical, democratic and digital logics are read and enacted.

Four layers can be distinguished analytically:

- Societal discourses—narratives of efficiency, innovation or crisis that legitimise technological interventions and orient expectations towards education.

- Institutional configurations—organisational priorities, accountability metrics and governance arrangements that determine how algorithmic systems enter pedagogical practice.

- Cultural and algorithmic imaginaries—symbolic meanings attached to digitalisation, personalisation or democratisation that shape how technologies are interpreted by actors.

- Biographical and lifeworld conditions—situated experiences through which profiling, recognition and agency are affirmed, negotiated or resisted.

Read in this way, framing makes visible how HE is entangled with wider socio-political struggles over visibility, legitimacy and subjectivity. The principle of non-disposability (Friesen & Kuntze, 2021) is introduced not as a prescriptive demand but as an analytical criterion derived from Bildung theory that marks moments where subjectivity exceeds functional reduction and recognition becomes fragile. While governance concerns the internal coordination of responsibility and accountability within institutions, framing refers to the socio-cultural horizons that shape how such coordination is interpreted and justified. Table 4 maps these framing layers across the three vertices of the DEA model.

Table 4.

Framing Structures of the DEA Model Across Dimensions.

3.5. Integrated Overview

To conclude the conceptual development of the DEA model, this section integrates its vertices, analytical dimensions, relational vectors, governance and framing structures into a coherent scaffold for inquiry. Together, these elements render visible how recognition, judgment and legibility shift when formative, normative and inferential logics intersect under algorithmic mediation. In doing so, the DEA model situates higher education within broader socio-technical and political struggles, rather than treating it as an autonomous pedagogical sphere. Outcome-oriented competence frameworks such as DigComp (Vuorikari et al., 2016), the OECD Learning Compass (Hughson & Wood, 2020) or ICILS (2023) provide structured indicators for evaluating educational performance. The DEA model approaches these frameworks from a different epistemic angle by interrogating how such indicators themselves emerge from shifting regimes of recognition and legibility. Rather than aligning educational processes to predefined metrics, it traces the conditions under which visibility, evaluability and legitimacy are produced in the first place. This diagnostic orientation does not aim to dissolve tensions but to make them analytically productive, showing where pedagogical discretion, democratic contestation or algorithmic governance become dominant in practice. In methodological terms, the framework supports diverse analytical strategies, including interface ethnographies, policy and document analyses, audit studies of algorithmic systems and qualitative reconstructions of recognition practices. Calibrated to higher education, the model responds to dynamics generated by assessment cultures, autonomy regimes and platform integrations. Applications in other educational sectors remain possible but would require re-specification of boundary conditions such as age-based governance, compulsory curricula and sector-specific data infrastructures. Table 5 consolidates these components into a single analytical matrix and locates their intersections across Education, Democracy and Digitalisation.

Table 5.

Components of the DEA Model across Education, Democracy and Algorithmic conditions.

4. Theoretical and Democratic-Pedagogical Implications for HE

The implications derived from the DEA framework address how pedagogical responsibility, democratic subject-formation and didactic relations change when algorithmic mediation becomes a normal condition of HE. Rather than prescribing fixed solutions, these implications identify zones of tension that invite empirical research, institutional reflection and pedagogical experimentation. Each field is directly linked to the relational logics and vectors developed in Section 3 and translates conceptual distinctions into operational entry points for inquiry and practice.

4.1. Pedagogical Responsibility: Negotiating Judgement Under Algorithmic Conditions

In education-oriented didactics (in the sense of Bildung), pedagogical responsibility is tied to interpretive judgement and attentiveness to learners as subjects of formation (Benner, 2025; Klafki, 1996). At its core, this understanding links professional responsibility to the educator’s capacity for discernment and to dialogical relations that cannot be automated. With the integration of algorithmic signalling systems, responsibility begins to operate in a hybrid regime where formative judgement coexists with procedural accountability to classificatory outputs. This tension reflects a broader shift from pedagogical discretion to data-driven standardisation. Comparable tensions have been observed in research on analytics-based governance, where data-driven indicators begin to reorient pedagogical agency (Williamson & Eynon, 2020). While current debates in digital citizenship education (Pangrazio & Sefton-Green, 2020; Selwyn, 2022) often focus on learners’ ability to navigate platforms critically, the DEA framework asks a different question: under what institutional and epistemic conditions can pedagogical judgement persist when algorithmic outputs start to claim authority over what counts as relevant? Teachers are expected to respond to learners directly while simultaneously acknowledging system-generated signals that claim evidential authority over performance and risk. This introduces a dual demand structure that makes (a) Recognition a contested practice, as educational visibility is negotiated between dialogical encounter and data legibility, while (c) Reflective Autonomy becomes crucial for sustaining interpretive agency. Empirical and pedagogical inquiry can therefore address how educators justify decisions that diverge from algorithmic prompts, how students interpret automated feedback in relation to their own judgement and how institutional expectations shape the balance between discretion and procedural compliance.

4.2. Democratic Subject-Formation: Visibility, Labelling and the Politics of Participation

As HE institutions integrate dashboards, recommender systems and predictive filters, learners appear as profiles that circulate through data infrastructures rather than as subjects encountered dialogically. This structural transformation raises a democratic question about who is visible, representable and heard within algorithmic environments. The shift resonates with critiques of data colonialism, which examine how legibility regimes redistribute epistemic authority (Couldry & Mejias, 2019). Work in democratic education (Amsler, 2015; Hess & McAvoy, 2015) highlights participation and voice. The DEA framework moves one analytical step further by asking what happens before participation becomes possible at all, namely, who is rendered visible in the first place and who remains outside the field of recognition. It invites democratic-pedagogical inquiry into whose contributions become visible, which trajectories remain opaque and how institutional labelling practices influence participation, dissent and self-perception. Pedagogical formats can respond by turning algorithmic categorisation itself into a topic of collective inquiry, allowing students to interrogate the categories that govern their visibility and to deliberate on fairness, bias and legitimacy. In terms of situated ethics, this implication is anchored in (a) Recognition and (b) Contestability, as it concerns both being seen and being able to question the terms of visibility.

4.3. Didactic Relations and Epistemic Authority: Algorithmic Guidance and Pedagogical Space

Teacher–learner, learner–content and teacher–content relations increasingly take shape through adaptive sequencing and recommendation architectures. Within these hybrid environments, pedagogical and algorithmic forms of guidance intertwine. These infrastructures reposition epistemic authority by placing algorithmic guidance alongside curricular design. Research on adaptive tutoring shows how learners oscillate between algorithmic advice and pedagogical instruction, adjusting their trust in each depending on perceived credibility (Ifenthaler, 2023). Building on this research, didactic inquiry can examine how educators recalibrate their role within such hybrid ecologies and how pedagogical norms evolve when sequencing and feedback are partially automated. For example, experimental curricula might intentionally introduce points of deviation from algorithmic pathways to foster reflective navigation of guidance and agency. Under a situated-ethical lens, this field foregrounds (c) Reflective Autonomy in relation to (d) Institutional Responsiveness, since meaningful engagement depends both on learners’ capacity to position themselves within algorithmic guidance and on institutions’ willingness to adjust infrastructures when classifications are contested.

4.4. Research Agendas and Institutional Development: From Diagnosis to Design

At the institutional level, the DEA framework extends beyond classroom interaction and can orient broader research and policy development. Debates on AI ethics emphasise transparency, fairness and accountability as institutional values, yet their translation into pedagogical settings remains unsettled (Dignum, 2019). Institutional approaches to AI ethics often reduce democratic values to procedural compliance—checklists and audits—rather than lived responsibility (Williamson, 2023). By contrast, the DEA framework brings these values back into the lived space of teaching and learning, where responsibility and responsiveness have to be negotiated in situated ways rather than proceduralised. Within democratic theory and sociology of education, the model offers analytical coordinates for examining how digital governance reshapes recognition, participation and professional responsibility. On a practical level, institutions can draw on these insights to develop participatory audit formats in which students and educators jointly evaluate classification procedures. Teacher education may include case-based exercises focused on interpreting and contesting algorithmic prompts, while governance bodies can embed (b) Contestability and (d) Institutional Responsiveness as explicit criteria in platform governance and procurement policies. Across these developments, the DEA framework transforms abstract ethical criteria into diagnostic instruments that connect recognition, autonomy, contestability and responsiveness with concrete pedagogical and institutional practices in HE.

Taken together, these implications show how the DEA framework functions as a situated-ethical matrix that links (a) Recognition, (b) Contestability, (c) Reflective Autonomy and (d) Institutional Responsiveness to concrete pedagogical practice, democratic participation and institutional governance in HE. The four criteria do not remain abstract but operate as diagnostic handles that support empirical research, didactic reflection and infrastructure design. Table 1 and Table 2 should therefore be read not as static summaries but as analytical tools, helping readers locate each implication within the model’s architecture and translate situated-ethical criteria into concrete strategies for action.

5. Conclusions and Outlook

The DEA framework has been introduced as a reflexive heuristic for examining how algorithmic mediation reshapes the formative and normative horizons of HE. Its contribution lies not in offering technical prescriptions but in articulating a conceptual orientation that resists both technological solutionism and nostalgic pedagogy. By situating higher education within a triangular constellation of education, democracy and digitalisation, the framework clarifies how pedagogical responsibility and democratic subjectivity can be interrogated without presuming their stability. In doing so, it reinforces the role of universities as spaces where educational formation and democratic publicness intersect.

From an education–theoretical perspective, the DEA approach extends classical accounts by showing that the unfinished character of formation requires systematic engagement with the technological and political conditions that co-structure the university. The theoretical significance of the framework lies in holding open the tensions that constitute democratic education under digital conditions. Rather than collapsing Bildung into competence acquisition, it foregrounds judgement, recognition and contestation as irreducible dimensions of subject-formation. This provides educational research with a diagnostic vocabulary for identifying when pedagogical responsibility drifts into algorithmic optimisation, when recognition becomes tethered to data legibility and when opportunities for dissent are displaced by procedural regularity. Such an understanding resonates with Biesta’s notion of subjectification, Rancière’s emphasis on interruption and Klafki’s conception of Bildung as critical engagement with the present.

Future research can extend these insights along three directions. First, empirical studies are needed to analyse how algorithmic infrastructures are embedded in governance regimes across institutional contexts and how they redistribute recognition and responsibility. Second, didactic experimentation could explore pedagogical practices that treat epistemic friction, delay and ambiguity not as deficits but as educational resources, for example in assessment formats that combine automated feedback with dialogical interpretation. Third, theoretical work can deepen the exchange between educational theory and democratic thought by placing deliberative and agonistic approaches in dialogue with the realities of digital governance. Such investigations may also draw on the evaluative coordinates of the framework (recognition, contestability, reflective autonomy and institutional responsiveness) to guide comparative analysis.

The broader implication is that HE cannot seek to eliminate tensions between pedagogy, democracy, and technology. Instead, it is called to develop reflexive pedagogies and democratic practices that inhabit these tensions productively. By sustaining opacity, alterity and contestation as conditions of learning, the DEA framework contributes to an educational orientation in which Bildung persists as an open and contested process and in which HE remains accountable to its democratic promise within digitally mediated environments. In this sense, the DEA framework can operate as a conceptual lens while also functioning as an orienting tool for institutional reflection and governance decisions under conditions of digitalisation.

Funding

The APC was funded by the Open Access Publication Fund of the SLUB/TU Dresden.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| DEA | Democratic Education under Algorithmic Conditions |

| HE | Higher Education |

Notes

| 1 | The theoretical perspectives discussed in this chapter do not aim to provide an exhaustive reconstruction of democratic, pedagogical or subjectivation theory. They offer a heuristic selection of influential approaches that illuminate different and sometimes conflicting dimensions of subject formation, recognition and democracy. Extending these perspectives to algorithmic mediation is a deliberate interpretive move that reveals how tensions reappear under digital conditions while maintaining the original orientation of the theories. |

| 2 | Digitalisation here designates the broader embedding of digital infrastructures, while the more specific logics of algorithmic mediation are addressed in Section 2.3. |

| 3 | The choice of education, democracy and algorithmic conditions as the vertices of the DEA model is deliberate, as they define the main conditions of higher education under digitalisation. Other domains such as economy or culture are considered only insofar as they affect pedagogy, legitimacy and digital infrastructures. The triangular constellation thus serves as a focused heuristic that highlights where formative, normative and technological forces converge. |

| 4 | The information presented in the tables of this paper represents illustrative examples of possible perspectives rather than comprehensive or exhaustive specifications. |

References

- Amoore, L. (2020). Cloud ethics: Algorithms and the attributes of ourselves and others. Duke University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amsler, S. S. (2015). The Education of radical democracy. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Apple, M. W. (1980). The other side of the hidden curriculum: Correspondence theories and the labor process. The Journal of Education, 162(1), 47–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barocas, S., Hardt, M., & Narayanan, A. (2023). Fairness and machine learning: Limitations and opportunities. MIT Press. Available online: https://fairmlbook.org/pdf/fairmlbook.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Bartok, L., Donner, M.-T., Ebner, M., Gosch, N., Handle-Pfeiffer, D., Hummel, S., Kriegler-Kastelic, G., Leitner, P., Tang, T., Veljanova, H., Winter, C., & Zwiauer, C. (2023). Learning Analytics—Studierende im Fokus. Zeitschrift für Hochschulentwicklung: ZFHE; Beiträge zu Studium, Wissenschaft und Beruf, 18, 223–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, M.-C., & Pöppelbuß, J. (2022). Prinzipien für die ethische Nutzung künstlicher Intelligenz. HMD Praxis der Wirtschaftsinformatik, 59, 468–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benner, D. (2025). Allgemeine Pädagogik. Eine systematisch-problemgeschichtliche Einführung in die Grundstruktur pädagogischen Denkens und Handelns (9th ed.). Beltz Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Biesta, G. J. J. (2010). Good education in an age of measurement: Ethics, politics, democracy. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Biesta, G. J. J. (2015). What is education for? On good education, teacher judgement, and educational professionalism. European Journal of Education, 50(1), 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biesta, G. J. J. (2017). The rediscovery of teaching. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, J. (1997). Excitable speech: Politics of the performative. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bünger, C., & Jergus, K. (2023). Bildung und Subjektivierung. Systematische Spannungslinien des Subjektivierungskonzepts im Kontext von Optimierung, Digitalisierung und Migration. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 26, 1389–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L., Chen, P., & Lin, Z. (2020). Artificial intelligence in education: A review. IEEE Access, 8, 75264–75278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Couldry, N., & Mejias, U. A. (2019). The costs of connection: How data is colonizing human life and appropriating it for capitalism. Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, A., Hagendorff, T., Li, H., Mann, M., Marda, V., Wagner, B., Wei Wang, W., & Witteborn, S. (2019). Artificial intelligence, governance and ethics: Global perspectives (The Chinese University of Hong Kong Faculty of Law Research Paper No. 2019-15). Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3414805 (accessed on 19 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education: An introduction to the philosophy of education. Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Dignum, V. (2017, August 19–25). Responsible autonomy: AI, ethics, and policy. Twenty-Sixth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence (IJCAI’17) (pp. 4698–4704), Melbourne, Australia. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dignum, V. (2019). Responsible artificial intelligence: How to develop and use AI in a responsible way. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donner, M.-T., & Hummel, S. (in press). Systematic literature review of AI-based mentoring in HE. In H.-W. Wollersheim, T. Köhler, & N. Pinkwart (Eds.), Scalable mentoring in HE. Technological approaches, teaching patterns, and AI techniques. in press. Springer.

- Egbringhoff, J., Kleemann, F., Matuschek, I., & Voß, G. G. (2023). Subjektivierung von Bildung bildungspolitische und bildungspraktische Konsequenzen der Subjektivierung von Arbeit. Arbeitsbericht. Institut Arbeit und Gesellschaft (INAG). [Google Scholar]

- Egger, R. (2006). Gesellschaft mit beschränkter Bildung. Eine empirische Studie zur sozialen Erreichbarkeit und zum individuellen Nutzen von Lernprozessen. Leykam. [Google Scholar]

- Egger, R. (2008). Biografie und Lebenswelt. Möglichkeiten und Grenzen der Biografie- und Lebensweltorientierung in der sozialen Arbeit. In J. Bakic, M. Diebäcker, & E. Hammer (Eds.), Aktuelle Leitbegriffe der sozialen Arbeit. Ein kritisches Handbuch (pp. 40–55). Löcker. [Google Scholar]

- Engel, J., & Kerres, M. (2023). Bildung in der nächsten Gesellschaft—Eine postdigitale Sicht auf neue formen der Subjektivierung. Ludwigsburger Beiträge zur Medienpädagogik (LBzM), 23, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eubanks, V. (2018). Automating inequality: How high-tech tools profile, police, and punish the poor. St. Martin’s Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feenberg, A. (1999). Questioning technology. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Feenberg, A. (2002). Transforming technology: A critical theory revisited. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. (1979). Überwachen und Strafen: Die Geburt des Gefängnisses. Suhrkamp. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. (1982). The subject and power. Critical Inquiry, 8, 777–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Continuum Books. [Google Scholar]

- Fricker, M. (2007). Epistemic injustice: Power and the ethics of knowing. Oxford Academic. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesen, M., & Kuntze, S. (2021). How context specific is teachers’ analysis of how representations are dealt with in classroom situations? Approaching a context-aware measure for teacher noticing. ZDM Mathematics Education, 53, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galle, M. (2021). Personalisiertes Lernen als pädagogisch-psychologisches didaktisches Konzept. In M. Galle (Ed.), Unterrichtszentrierte Schulentwicklung (pp. 29–37). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, D. R., Anderson, T., & Archer, W. (2000). Critical inquiry in a text-based environment: Computer conferencing in higher education. The Internet and Higher Education, 2, 87–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giroux, H. A. (2015). Neoliberalism’s war against he and the role of public intellectuals. Revista Interdisciplinaria de Filosofía y Psicología, 10(34), 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Gudjons, H. (2012). Pädagogisches Grundwissen (11th ed.). Verlag Julius Klinkhardt. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, J. (1981). Theorie des kommunikativen Handelns. Suhrkamp. [Google Scholar]

- Hess, D. E., & McAvoy, P. (2015). The political classroom. Evidence and ethics in democratic education. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Honneth, A. (1994). Kampf um Anerkennung: Zur moralischen Grammatik sozialer Konflikte. Suhrkamp. [Google Scholar]

- Hughson, T. A., & Wood, B. E. (2020). The OECD learning compass 2030 and the future of disciplinary learning: A bernsteinian critique. Journal of Education Policy, 37(4), 634–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel, S. (2021). Learning analytics—Ein hochschuldidaktisches Begleitprogramm zur prozessorientierten Lernunterstützung. FNMA-Magazin, 21–24. Available online: https://fnma.at/content/download/2305/12827?version=2 (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Hummel, S., Donner, M.-T., Abbas, S. H., & Wadhwa, G. (2025). Bildungstechnologiedesign von KI-Gestützten Avataren zur Förderung Selbstregulierten Lernens. In T. Köhler, E. Schopp, N. Kahnwald, & R. Sonntag (Eds.), Community in new media. Trust in crisis: Communication models in digital communities: Proceedings of 27th conference GeNeMe (pp. 197–209). TUDpress. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel, S., Donner, M.-T., & Egger, R. (in press). Turning tides in HE? Exploring AI’s role in qualification, self-education and socialization. In H.-W. Wollersheim, T. Köhler, & N. Pinkwart (Eds.), Scalable mentoring in HE. Technological approaches, teaching patterns and AI techniques. in press. Springer.

- Ifenthaler, D. (2023). Ethische Perspektiven auf künstliche Intelligenz im Kontext der Hochschule. In T. Schmohl, A. Watanabe, & K. Schelling (Eds.), Künstliche Intelligenz in der Hochschulbildung. Chancen und Grenzen des KI-gestützten Lernens und Lehrens (pp. 71–86). Transcript. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Computer and Information Literacy Study (ICILS). (2023). Main findings and educational policy implications. Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2766/5221263 (accessed on 19 September 2025).

- Jackson, P. (1968). Life in classrooms. Holt, Rinehart & Winston. [Google Scholar]

- Klafki, W. (1996). Neue Studien zur Bildungstheorie und Didaktik: Zeitgemäße Allgemeinbildung und Kritisch-Konstruktive Didaktik (7th ed.). Beltz. [Google Scholar]

- Knox, J., Williamson, B., & Bayne, S. (2020). Machine behaviourism: Future visions of ‘learnification’ and ‘datafication’ across humans and digital technologies. Learning, Media and Technology, 45(1), 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koller, H.-C. (2023). Bildung anders denken. Einführung in die Theorie transformatorischer Bildungsprozesse (3rd ed.). Kohlhammer. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, P., & Koehler, M. J. (2006). Technological pedagogical content knowledge: A framework for teacher knowledge. Teachers College Record, 108(6), 1017–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mounk, Y. (2018). The people vs. democracy: Why our freedom is in danger and how to save it. Harvard University Press. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv24trckb (accessed on 10 September 2025).

- Negt, O. (2010). Der politische Mensch. Demokratie als Lebensform. Gefälligkeitsübersetzung: The political person. Democracy as a way of life. Steidl Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, P., & Inglehart, R. (2019). Cultural backlash: Trump, brexit and authoritarian populism. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum, M. C. (2000). Women and human development: The capabilities approach. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussbaum, M. C. (2010). Not for profit: Why democracy needs the humanities. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pangrazio, L., & Sefton-Green, J. (2020). The social utility of data literacy. Learning, Media and Technology, 45(2), 208–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, K., Brown, M., Brooks, D. C., McCormack, M., Reeves, J., & Arbino, N. (2021). 2021 educause horizon report, teaching and learning edition. Educause. [Google Scholar]

- Puentedura, R. R. (2013). SAMR: Getting to transformation. Available online: http://www.hippasus.com/rrpweblog/archives/2013/04/16/SAMRGettingToTransformation.pdf (accessed on 14 September 2025).

- Rancière, J. (1991). The ignorant schoolmaster: Five lessons in intellectual emancipation. Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Redecker, C. (2017). European framework for the digital competence of educators: DigCompEdu (EUR 28775 EN). Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmohl, T., Watanabe, A., & Schelling, K. (2023). Künstliche Intelligenz in der Hochschulbildung: Chancen und Grenzen des KI-gestützten Lernens und Lehrens. Eine Einführung in die Beiträge des Bandes. In T. Schmohl, A. Watanabe, & K. Schelling (Eds.), Künstliche Intelligenz in der Hochschulbildung (pp. 7–26). Transcript Verlag. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selwyn, N. (2022). The future of AI and education: Some cautionary notes. European Journal of Education, 57(4), 620–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemens, G. (2013). Learning analytics: The emergence of a discipline. American Behavioral Scientist, 57, 1380–1400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terhart, E. (2011). Lehrerberuf und Professionalität. Gewandeltes Begriffsverständnis–Neue Herausforderungen. In W. Helsper, & R. Tippelt (Eds.), Pädagogische Professionalität (pp. 202–224). Beltz. [Google Scholar]

- Terhart, E. (2019). Lehren und Lernen. In J. Drerup, & G. Schweiger (Eds.), Handbuch Philosophie der Kindheit (pp. 145–151). J.B. Metzler. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uljens, M. (2023). Non-affirmative theory of education and bildung. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Von Hentig, H. (1996). Bildung. Ein essay. Beltz Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Von Thiessen, R., & Volz, S. (2023). Künstliche Intelligenz in der Bildung. Rechtliche Best Practices. Kanton Zürich. Available online: https://www.zh.ch/content/dam/zhweb/bilder-dokumente/themen/wirtschaft-arbeit/wirtschaftsstandort/dokumente/best_practices_ki_bildung_de_v2.pdf (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Vuorikari, R., Punie, Y., Carretero Gómez, S., & Van den Brande, G. (2016). DigComp 2.0: The digital competence framework for citizens. Update phase 1: The conceptual reference model (EUR 27948 EN). Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, B. (2023). Governing through infrastructural control: Artificial intelligence and cloud computing in the data-intensive state. In W. Housley, A. Edwards, R. Beneito-Montagut, & R. Fitzgerald (Eds.), The sage handbook of digital society (pp. 521–539). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson, B., & Eynon, R. (2020). Historical threads, missing links, and future directions in AI in education. Learning, Media and Technology, 45(3), 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).