A Portrait of a Native Hawaiian Ethnomathematics Educator

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Research Questions

- (1)

- What contradictions and tensions must C-VMTOC’s occupy and confront if they wish to bring de/colonial and/or ethno-mathematical practices into their teaching praxis?

- (2)

- How do the ‘contradictions and tensions’ referred to in RQ1 impact C-VMTOC’s own burgeoning critical consciousness and complex mathematical personhood (Rezvi, 2025)?

- (3)

- How do C-VMTOC’s work within (and simultaneously subvert) colonial systems of education?

Researcher Ni’yaat (Intention/نِيَّة)ٌ

…portraiture has become the bridge that has brought these two worlds together for me, allowing for both contrast and coexistence, counterpoint and harmony in my scholarship and writing, and allowing me to see clearly the art in the development of science and the science in the making of the art.(2002, p. 3).

3. Theoretical Framework

3.1. MathematX

3.2. Decolonization/Colonization

- Bhattacharya writes,

I have always conceptualized a decolonizing agenda to be forever entangled with colonialism. These terms are binary opposites, with one representing freedom and the other enslavement. However, by writing de/colonizing with a slash I disrupt the notion of a pure, discrete binary relationship between colonial oppression and the decolonial desires of resistance and freedom. I choose this disruption to emphasize that there are no pure (real or imagined), utopian spaces devoid of resistance to colonialism, because the resistance implies being in an oppositional relationship with colonialism. Those of us who resist colonization often live in hybridized spaces where we shuttle between encounters with colonial oppression, internalized forms of colonization, utopian dreams of decolonization, and mitigated resistance to colonial oppression in ways that are strategic to our survival. By introducing a slash in the word, I demonstrate the relationality, the movement, and the impermanence of both colonialism and its resistant counterpart. This move conveys a hybrid state of being, knowing, existing, resisting, and accommodating across, within, and against de/colonialism.(p. 177)

- Bhattacharya’s recognition that de/colonization is entangled with past, present, and future, and that we all, in our complexity (and complicity), live within these hybridized spaces, parallels the multiplicity of knowings Gutiérrez describes in her conceptual framing of mathematX. This also aligns with my theorization of Complex Mathematical Personhood (CMP) as a lens for understanding how teacher identities are constructed and evolve over time. I view Bhattacharya’s call for care and intention when it comes to the term de/colonization as a reminder that all of us are Learning & (Un)Learning [CMP 4] and continuously engaged in the acts of Remembrance and Forgetting [CMP 1] in the ways in which we view and forge our own mathematical identities within the colonial borders of the United States of America.

3.3. Complex Mathematical Personhood

- According to Gordon,

Complex personhood means that all people...remember and forget, are beset by contradiction, and recognize and misrecognize themselves and others. Complex personhood means that people suffer graciously and selfishly too, get stuck in the symptoms of their troubles, and also transform themselves. Complex personhood means that even those called “Other” are never never that. Complex personhood means that the stories people tell about themselves, about their troubles, about their social worlds, and about their society’s problems are entangled and weave between what is immediately available as a story and what their imaginations are reaching towards. Complex personhood means that even those who haunt our dominant institutions and their systems of value are haunted too by things they sometimes have names for and sometimes do not. At the very least, complex personhood is about conferring the respect on others that comes from presuming that life and people’s lives are simultaneously straightforward and full of enormously subtle meaning.(2008, pp. 4–6)

- Inspired by Gordon’s conception of complex personhood and Gutiérrez’s surfacing of mathematX, I suggest that complex mathematical personhood [CMP] can be constructed as a theoretical framework as follows:

4. Definition of Critical Veteran Mathematics Teacher of Color

5. Positionality

6. Methods

6.1. Portraiture and Case Study—An Overview

- As Lightfoot notes,

Surely analysis and solidarity could stand as two poles of scholarship. Much research has neglected the second, studying teachers, for example, as though they were fruit flies…It is in the quest of the empowerment that comes from looking beyond the isolation at the little difference there is between humans, and the supreme importance of that difference. It searches for the energizing shock of sympathy and of the human community.(Oakley, pp. 375–376, as cited by Lightfoot, p. 10)

- I utilize a combination of portraiture and case study methods. Data included collecting teaching artifacts such as student letters that had an affective impact on the participant, copies of unit or lesson plans that were critically oriented in nature, semi-structured interview prompts, and readings and reactions to a poem all participants read. In Kahiau’s case, a picture of a handmade woven vase was emailed to me, and explained in detail about what the weaving represents for his teaching praxis. The data sources provided the ability to develop a thick description and construct analysis via NVivo that proved very generative in connecting larger emergent themes. For much of this study, I connected how the larger macro socio-political context that teachers face can be found in the particular daily milieu that construct VMToC’s experiences in their workplaces and mathematics classrooms. As Geertz (1973) observes, “small facts are the grist for the social theory mill” (p. 23).

[Int. 1, 4 February 2024, Kahiau]Sara: 44:09...But you know, I’m just really honored that our ancestors, however, they were with us, are here in this conversation today. Like the fact that you brought that up and were willing to share that with me… I’m humbled and I’m honored because this is literally the second time we’re talking and we’re just like sitting here crying…[Sara wiping tears]

Kahiau 44:53...because we’re Indigenous people! That’s what Indigenous people do.[also weeping on camera]

6.2. Hawaiian Contextualization

7. Findings

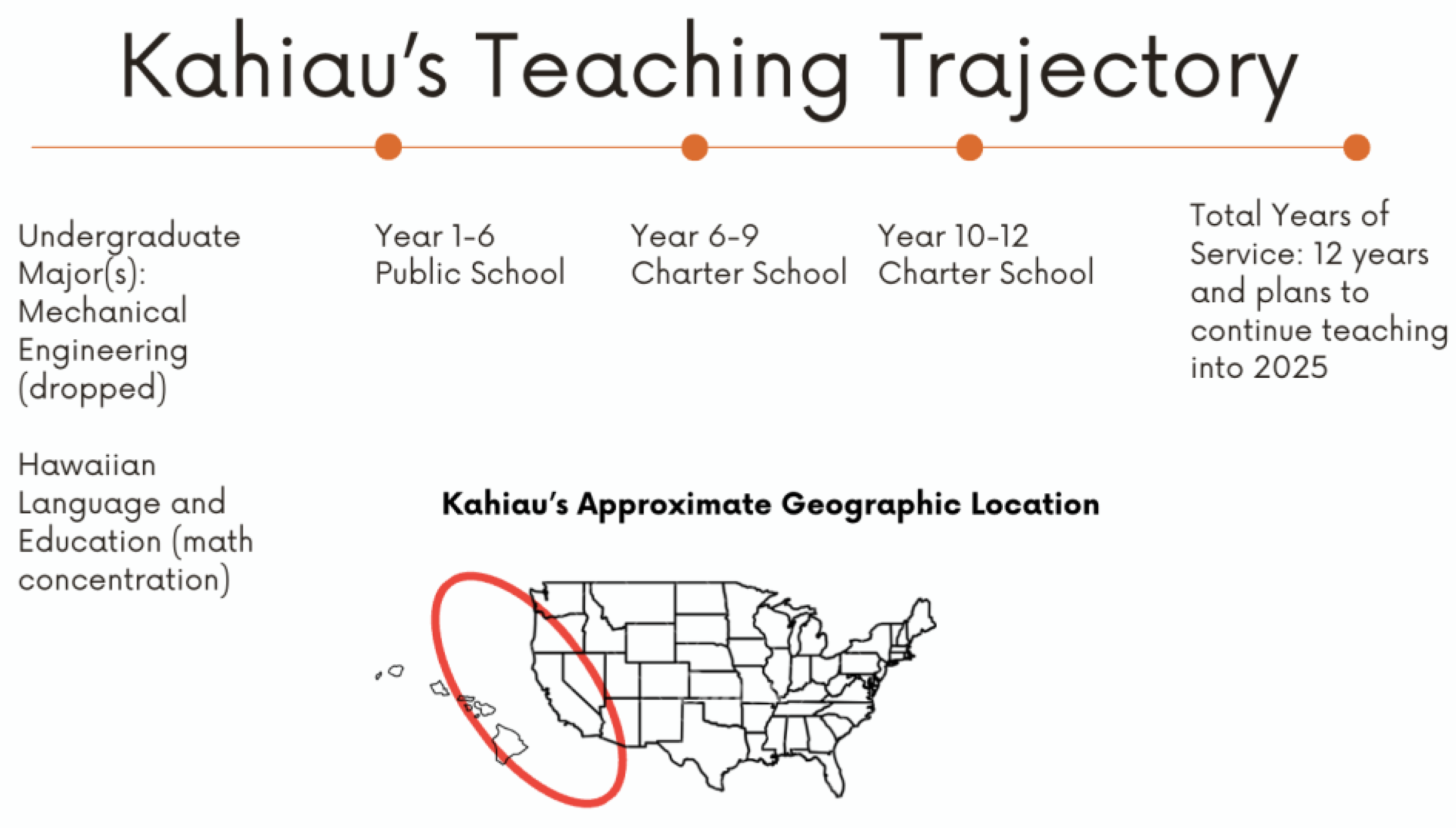

Introducing Kahiau

8. Kahiau’s Portrait

I’m fighting to decolonize. But I don’t recognize that I’m colonized myself~[Kahiau, Int. 1 (pt 1), 17 December 2023]

9. Complex Mathematical Personhood: Socio-Historical and Socio-Cultural Navigations

For me, I guess in Hawaii because of our colonized history there, every Hawaiian person will list you their entire list of mixed race. And I remember, at one point maybe in high school, it came down to who has the most ethnic backgrounds in your ancestry. And I’m actually surprisingly, I’m one of those smaller ones…[my parents] raised us very, what we call, loco style. That’s a term we use in Hawaii... My mom is Filipino-Japanese, my dad was Hawaiian, Chinese, everything else, Samoan, Irish…Also, all I know is that I’m the first in my family, in maybe three or four generations, to speak Hawaiian. My papa, my Filipino grandfather. I know he spoke Bisaya [a FilipinX language]…my mom said they remember as kids hearing it, but they were never spoken to in Bisayan. So it’s just this colonized era, you know the 20th century.~[Int. 1 (pt 1), 17 December 2023]

- The history of the colonization of Hawaii and its ongoing present-day occupation by the United States government reflects and refracts into the dynamics of how Kahiau experiences his day-to-day teaching life. I offer his insights in this section to highlight the linkages between land, Indigeneity, and his ethnomathematics teaching philosophy here in response to the first and second research questions for this study.

So, for me to identify came down to the food and just the little bits of superstition here and there. But I think that’s why when I finally took Hawaiian language courses and Hawaiian studies courses, I didn’t realize that there’s been in local culture so much Hawaiianness is embedded in there. It just evolved. I got mixed up in the diaspora of everybody else…I’m now identified because I practice my Hawaiian culture.[Int. 1, 17 December 2023]

- For Kahiau, reclaiming language and practicing Hawaiian culture are central to his de/colonization praxis. This includes his evolving spiritual practices rooted in Native Hawaiian traditions such as hula, his commitment to ensuring that future kānaka maoli [Indigenous Hawaiian person] generations do not face the same barriers he encountered in pursuing STEM pathways, and his integration of cultural connections between people, language, and mathematics into his daily teaching.

Well, I’m open to any job. I’m excited…I’m ready to explore whether there’s two major divisions that mechanical engineers are sent to. And there’s just a regular engineering division, HVAC—heating, ventilation. Basic mechanical stuff usually, because it’s Pearl Harbor. It’s a naval fleet. …the other one was nuclear engineering. So, they placed me in nuclear engineering, which is fine. But it was the most boring job ever. And it’s primarily because of all the red tape of the United States government. It was you just sat there the whole summer at a desk. But because I didn’t have top level clearance for a lot of the things in my department, I couldn’t do anything…I got paid a nice federal paycheck to just sit there…Maybe you’re busy in meetings, but that’s like the extent of your social life. It’s just meeting with other engineers talking about how we’re going to maintain the fleet.[Int. 1 (pt 1), 17 December 2023]

- In particular, the beginning of this endeavor was deeply connected to his reconnection to the Hawaiian language. Kahiau clarifies that:

…anywhere in the UH system, it is required that students take a Hawaiian course and take Hawaiian studies, Hawaiian language. So, the majority of students, I would say like 80% plus take Hawaiian studies… And we get a very surface level in the high school system…And I realized, wow, I am a native Hawaiian living in Hawaii. And I don’t know my own language. So, I decided to take the course as an elective, obviously. And eventually I tried to make it a double major with engineering and Hawaiian. And I also participated in this program… where they have year-round weekend or one week, two week long activities for Native Hawaiian students [in] K12. And one of my scholarships I had was to volunteer. So, taking that program, understanding that I am a Hawaiian student who is studying for engineering, and I can help other students K 12, who love STEM, one of the STEM course routes was available and that’s when I realized I wanted to be an educator.[Int. 1 (pt 1), 17 December 2023]

- Connecting language, literacy and mathematics was essential to Kahiau’s mathematical identity as well. However, this was further challenging because he was one of the few native Hawaiian people studying both STEM and Hawaiian language; a reality of both the mathematical field as a largely White institutional space but also the recognition that the field of education is itself also a White institutional space as well. Part of Kahiau’s master’s thesis work involved looking through Hawaiian textbooks that missionaries had translated from French from the 1800s. He describes discovering mathematics as a form of poetry in his native language, an experience that was both exhilarating and isolating, like stumbling upon a secret song with no one else to sing it with.

So, it was…it was hard for me, I had to just navigate it myself. Because I remember when I did my thesis, I looked through textbooks from the 1800s. Because there were Hawaiian textbooks that missionaries translated from French textbooks. So, reading through, they were so fascinating to me, because I had to know Hawaiian language and mathematics…there was a book explaining what a plane was…And the words they were using was like, wow, is there a beautiful Hawaiian word, I feel like looking it up, because I never knew a bunch of them. But [it was said so] beautifully and poetically, where it’s a surface that goes on forever and never without any wrinkles…. beautiful terminology, because Hawaiian is a poetic language. This is beautiful. But no one else can understand this except me. Like, it’s, I felt empowered because I had this little pearl.~[Int. 1 (pt 1), 17 December 2023]

- After teaching in a few different schools during his initial teaching years, Kahiau was hired due to his background in ethnomathematics and his ability to braid Hawaiian culture and STEM at a school that predominantly serves native Hawaiian students. The school itself is engaging in a collective and collaborative act of de/colonizing the curriculum and intentionally creating spaces for faculty and staff to have conversations about how to do this work together, including reading Paulo Freire’s work. Kahiau observes the following:

We had to read excerpts of Paulo Freire. I love…a lot of what Dr. Freire says in his book …it really hit us hard... But once we realized, for me, it was I am the colonizer by continuing this path [referring to working at Pearl Harbor]…Okay, no, I can’t do this. I’m fighting to decolonize. But I don’t recognize that I am colonized myself (emphasis added). Oh, boy [K visibly emotional on camera]. That was the one that did it for me…I need to hold on to my math, I need to hold on to ELA because of math test scores. And then we were like, Wait a minute. Yeah, what are we doing? So it hit us hard. And now we’re just like, alright, let’s just flood the gates. Decolonize everything we’re doing. But for some teachers, it’s very difficult, because they have not hit that wall, or they’re too afraid to hit that wall of, wow, I’m colonized. Some of our White faculty, I think it is also hard…for them to realize too, where they are because of the education system, not because of who they are. It’s the system.[Int. 1 (pt 1), 17 December 2023]

- Kahiau’s observation is revelatory in several ways in response to the second and third research questions, which concern the contradictions and tensions C-VMTOCs occupy and confront in their teaching praxis and the CMP framework: (1) it embodies the ‘epistemology of knowledges’ central to Gutiérrez’s MathematX conceptualization; (2) it highlights [CMP 4], the attribute of learning and (un)learning as mutually entangled phenomena; (3) it underscores that this work is ongoing and shaped dialectically by both individual and collective actions within the school community as described by the slash in Bhattacharya’s explanation of de/colonization; and (4) it invites reflection on how White faculty members may experience and engage with this process differently under systems of oppression as an extension of [CMP 3], socio-historical and socio-cultural navigations.

9.1. Complex Mathematical Personhood: Remembrance and Forgetting

…presenting Western and Indigenous knowledges as “opposites” has been the strategy of colonizers who suggest Indigenous knowledges are in contrast to Western ones that have served as the foundation for progress in the modern world (Harding, 2008). So, while there is no such thing as a single Indigenous “way of knowing” or “worldview,” there are underlying epistemologies (ways of knowing) and ontologies (views of reality) that differ from modern Western/Northern/Eurocentric views and that contribute to Indigenous systems (Battiste et al., 2002; Cajete, 2000)(p. 3)

- In the act of writing and bearing witness to Kahiau’s narration of his complex mathematical personhood and how it has evolved for him over time, I kept returning to Gutiérrez’s (2019) concept of mathematX. I wondered about all the ways in which Kahiau had experienced dispossession both as something that could be seen and observed physically and in what ways he had experienced the kind of dispossession Gutiérrez is describing from an epistemological orientation in mathematics spaces. I respond to the second research question below by offering an example of how Kahiau engages in the act of living mathematX epistemologically and through the lesson plan/unit plan he shared with me along with his thoughts behind the creation of the unit of study.

- RQ (1): What contradictions and tensions must C-VMTOC’s occupy and confront if they wish to bring de/colonial and/or ethno-mathematical practices into their teaching praxis?

…I’m still held to this darn standardized test. And that’s the one that every teacher now that we’re in this decolonization process, every teacher is trying to dismantle. Stop making required standardized test scores…like, stop it…I want to see the progress for sure. But don’t hold it against us. Me and the ELA teacher go back and forth on it…math is not just here’s a score, the score will dictate that if you can maintain this trajectory… you will have the opportunity to get into Stanford or Princeton. You can get to it regardless of that. …I think that’s what I want to be known for. And it just sucks that there’s parts of me that I have to hold it down because I’ve got to teach to the test a little bit.[Int. 1 (pt 2), 4 February 2024]

- The lesson plan Kahiau shared with me reflects his own grappling with the powerful statement he made earlier in our conversation: “I’m fighting to de/colonize. But I don’t recognize that I am colonized myself” [Int. 1, 17 December 2023].

…our school is, I think I mentioned [this]…we’re trying to decolonize our efforts or the histories that we have. So, my team, also last year was our first year of our pilot to Indigenize the school.[Int. 1 (pt 1), 17 December 2023]

- RQ (2): How do the ‘contradictions and tensions’ referred to in RQ1 impact C-VMTOC’s own burgeoning critical consciousness and complex mathematical personhood

Our most successful cornerstone last year that we’re trying to duplicate this year was the Socratic seminar. Because that’s one of the skills for English and they had to debate. If Hawaii had one sustainable food crop, what would it be and why? So they have to take my skills of ratios and, and rates to talk about yields of crops, how much it can feed and how much calories for family and health they learn about calories and the balanced diet. What is a calorie? What is this? Science? They also learn about calories but also…the scientific part: the burning rate? How does it affect your body?[Int. 1 (pt 2), 4 February 2024]

- When describing the unit and the underlying affective goals of what he hoped students would attain out of this experience, Kahiau shared the following:

Students need to play. Students need to value feedback. Students need to have multi-generational teaching practices… We know our ancestral roots; we know our genealogies. And that’s integral in every classroom. And there’s even voice and choice. Every child. Every lesson is personalized to every child, they can do this, this is, and we took that document and we’re like, Hey, what are we going to do for our sixth graders?[Int. 1 (pt 1), 17 December 2023]

- Part of the act of CMP 4 (learning and (un)learning) and CMP 1 (remembrance and forgetting) Kahiau is describing in this narration is the importance of honoring the humanity and ancestral ties of every single child in his mathematics classroom. As readers who have been in the K12 classroom might attest, this is easier said than done; those that are the most vulnerable are the ones who are most often invisibilized daily in mathematics spaces. For middle and high school mathematics teachers, the desire to fully see and personalize the teaching experiences for every child can be in direct tension with the structural reality of scheduling and attempting to create these spaces for upwards of a 100+ children daily. It was the school’s explicit commitment to de/colonizing that made interdisciplinary planning possible, allowing Kahiau and his colleagues to engage in this level of intentional collaboration as a team, rather than attempting to do so in isolation.

9.2. Complex Mathematical Personhood: Harm and Joy

- RQ (3): How do teachers of color work within (and simultaneously subvert) colonial systems of education?

I learned that in Hawaiian pedagogy, it’s… usually the Elder, the Kūpuna, the ancestor, grandparent, that teaches the child, while the adult parent is the one hunting or fishing or farming or doing that…all those things. And learning was always one on one, or one on two, very small, very small ratio. And I’m like, I can’t teach this class of 25 with these struggles, like there’s gotta be something better. And that’s how I stumbled upon ethnomath.[Int. 1 (pt 1), 17 December 2023]

- When describing the actual enactment of the unit plan summarized in Table 2, Kahiau noted the powerful line from one of his students emphasized below:

We had our Socratic seminar. The kids were doing their thing. I was like, wow, these kids were amazing…They’re sixth graders, and they’re debating about whether we want kalo [taro plant in the Hawaiian language] or [not]... And we’re amazed…And watching some of these kids have good audience technique to present in front of their entire class [of more than a hundred] sixth graders, and they watched every single debate…it was amazing. And one of the comments that made us like… (Kahiau stops and gets visibly emotional) one student said, I have permission to be smart (emphasis added). You see why? Okay, that was like, oh my god, this works. We teach an Indigenous way that works.[Int. 1 (pt 2), 4 February 2024].

- I am reflecting on a question Gutiérrez asks regarding the embedded ways in which Western/Eurocentric mathematics serves as a site of dispossession. She wonders: ‘What is lost in mathematics as a whole, and in global society, if we continue to dispossess people of valuable knowings that support them to be whole—to continually remake themselves and fulfill their responsibilities—and that have the potential to enrich the lives of others, including our other-than-human relatives? (Gutiérrez, 2019, p. 5).’

9.3. Complex Mathematical Personhood as Revolution

When I was taught to weave, my kumu [teacher] said not to fight the lau [leaf]. Let the lau do what it wants to do and I am merely there to guide the leaf into place. The same goes for our students, I do my very best not to indoctrinate and try to just guide them. Once the weaving project is complete, the interconnectedness of each leaf creates a beautiful artifact and with our students, we always connect them and network with them with their peers, their families, and the community. Ultimately, we want them to network with each other because this creates our beautiful lāhui [nation] and kaiāulu [community]. Our Hawaiian values are built upon community and proactive planning rather than the individual nuclear families and selfish behavior. I also wove three flowers (in order from L to R, loke [rose], anthurium, and putiputi [Māori flower]. These flowers are three different techniques that come with networking with people from outside our community. We can still learn from people that are different from us and that will only make us more beautiful. I also took this photo on my front patio. I have been learning to become more patient every time I work in my front yard which in turn is helping me become more patient with my 6th graders.[Personal Correspondence, 5 March 2024]

My teacher of hula would always tell us when we do particular chants for either rain or the sun for inspiration. She always tells us…when you get your answer, don’t be surprised. You asked for it. And if you are genuine, it’s going to come to you. So don’t be surprised when it actually happens. Every time I ask for my prayer, I do my chanting. I’m not shocked anymore.~[Int. 3, 3 March 2024]

- Kahiau’s reclamation of spiritual traditions like hula, weaving, and ethnomathematical teaching practices are prayers answered for him. In our final interview together, we both wept from our corners (and digital screens) in the world at the beauty and grief of bearing witness to our respective experiences and for allowing the universe to connect us together. In the writing of this portrait, I am grateful for my own prayers answered on what it means to be a principled remainer in our current socio-political realities.

9.4. Limitations of the Study

9.5. Further Discussion

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CMP | Complex Mathematical Personhood |

| C-VMTOC | Critical Veteran Mathematics Teachers of Color |

| 1 | I align with Rosemary Campbell-Stephen’s definition of global majority as a [collective term that first and foremost speaks to and encourages those so-called to think of themselves as belonging to the global majority. It refers to people who are Black, Asian, Brown, dual-heritage, indigenous to the global south, and/or have been racialized as ‘ethnic minorities’] from her LinkedIn talk Global Majority; Decolonising the language and Reframing the Conversation about Race (2020). Due to the current literature that uses the term ‘people of color’, I use Global Majority and people of color synonymously but define both terms. |

| 2 | to the extent that this is even possible given the ways in which academia, writ large, is constructed and in which I am also complicit and constructed with(in). |

| 3 | Out of respect for Kahiau’s learning community and his request to keep parts of the data he shared with me private, I will not be sharing the other aspects connected to what his colleagues were simultaneously teaching in their science, language arts, and social studies classes. |

References

- Alsup, J. (2006). Teacher identity discourses: Negotiating personal and professional spaces. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson-Pence, K. L. (2015). Ethnomathematics: The role of culture in the teaching and learning of mathematics. Utah Mathematics Teacher, 3(2), 52–60. [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, D. J. C., & Castillo, B. M. (2016). Humanizing pedagogy for examinations of race and culture in teacher education. In Race, equity, and the learning environment (pp. 112–128). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum, P., & Davila, E. (2007). Math education and social justice: Gatekeepers, politics and teacher agency. Philosophy of Mathematics Education Journal, 22, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, C. N. (2024, February 8). Project 2025: The right’s dystopian plan to dismantle civil rights and what it means for women. Ms. Magazine. Available online: https://msmagazine.com/2024/02/08/project-2025-conservative-right-wing-trump-woke/ (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Battey, D., & Franke, M. L. (2008). Transforming identities: Understanding teachers across professional development and classroom practice. Teacher Education Quarterly, 35(3), 127–149. [Google Scholar]

- Battiste, M., Bell, L., & Findlay, L. M. (2002). Decolonizing education in Canadian universities: An interdisciplinary, international, indigenous research project. Canadian Journal of Native Education, 26(2), 82–95. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, K. (2019). (Un)settling imagined lands: A par/des(i) approach to de/colonizing methodologies. In P. Leavy (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of methods for public scholarship (p. 34). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Borba, M. C. (1987). Urn Estudo De Etnomatematica: Sua incorporaçao na elaboraçao de uma proposta pedagogica para o “Nucleo-Escola” da Vila Nogueira-Sâo Quirino [Master’s thesis, UNESP]. [Google Scholar]

- Bullock, E. C., & Meiners, E. R. (2019). Abolition by the numbers mathematics as a tool to dismantle the carceral state (and build alternatives). Theory Into Practice, 58(4), 338–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cajete, G. (2000). Native science. Clear Light Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Clandinin, D. J., Connelly, F. M., & Bradley, J. G. (1999). Shaping a professional identity: Stories of educational practice. McGill Journal of Education, 34(2), 189. [Google Scholar]

- Coates, T.-N. (2017, October). The first white president. The Atlantic. [Google Scholar]

- D’Ambrosio, B., Frankenstein, M., Gutiérrez, R., Kastberg, S., Martin, D. B., Moschkovich, J., Taylor, E., & Barnes, D. (2013). Positioning oneself in mathematics education research: JRME Equity Special Issue Editorial Panel. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 44(1), 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Ambrosio, U. (1985). Ethnomathematics and its place in the history and pedagogy of mathematics. For the Learning of Mathematics, 5(1), 44–48. [Google Scholar]

- Darragh, L. (2016). Identity research in mathematics education. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 93, 19–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drake, C., Spillane, J. P., & Hufferd-Ackles, K. (2001). Storied identities: Teacher learning and subject-matter context. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 33(1), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enyedy, N., Goldberg, J., & Welsh, K. M. (2006). Complex dilemmas of identity and practice. Science Education, 90(1), 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewing, E. L. (2018). Ghosts in the schoolyard: Racism and school closings on Chicago’s South Side. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Finney, B., Kilonsky, B., Somesom, S., & Stroup, E. (1986). Re-learning a vanishing art. Journal of the Polynesian Society, 95, 41–90. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed (M. B. Ramos, Trans.). Herder & Herder. (Original work published 1968). [Google Scholar]

- Frenkel, S., & Odenheimer, N. (2025, April 25). Israel’s A.I. experiments in Gaza war raise ethical concerns. The New York Times. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2025/04/25/technology/israel-gaza-ai.html (accessed on 24 May 2025).

- Furuto, L. H. L. (2014). Pacific ethnomathematics: Pedagogy and practices in mathematics education. Teaching Mathematics and Its Applications:An International Journal of the IMA, 33(2), 110–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, N. K., Heath, G., Cameron, E., Rashid, S., & Redwood, S. (2013). Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gee, J. (2000). Identity as an analytic lens for research in education. Review of Research in Education, 25, 99–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geertz, C. (1973). The intrepretation of cultures. Basic Books. Available online: https://cdn.angkordatabase.asia/libs/docs/clifford-geertz-the-interpretation-of-cultures.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Gordon, A. (2008). Ghostly matters: Haunting and the sociological imagination. University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gresalfi, M. S., & Cobb, P. (2011). Negotiating identities for mathematics teaching in the context of professional development. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 42(3), 270–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, R. (2013). The sociopolitical turn in mathematics education. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 44(1), 37–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, R. (2017). Living mathematx: Towards a vision for the future. North American chapter of the international group for the psychology of mathematics education. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED581384 (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Gutiérrez, R. (2019, January 28–February 2). MathematX: Towards a way of being. 10th International Mathematics Education and Society Conference, Hyderabad, India. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, R. (2023). Mathematx: Towards a way of being (working paper). University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. [Google Scholar]

- Gutstein, E. (2006). Reading and writing the world with mathematics: Toward a pedagogy for social justice. Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Gutstein, E., & Peterson, B. (2006). Rethinking mathematics: Teaching social justice by the numbers. Rethinking Schools, Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Hammond, Z. (2014). Culturally responsive teaching and the brain: Promoting authentic engagement and rigor among culturally and linguistically diverse students. Corwin Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harding, S. (2008). Sciences from below: Feminisms, postcoloniality, and modernities. Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hauser, C., & Vigdor, N. (2025, January 24). U.S. embassy flag rules now ban BLM and pride flags. The New York Times. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2025/01/24/us/embassy-us-flag-blm-gay-pride.html (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Hogan, M. P. (2008). The tale of two Noras: How a Yup’ik middle schooler was differently constructed as a math learner. Diaspora, Indigenous, and Minority Education, 2(2), 90–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, J. D., Smail, L., Corey, D., & Jarrah, A. M. (2022). Using Bayesian Networks to provide educational implications: Mobile learning and ethnomathematics to improve sustainability in mathematics education. Sustainability, 14(10), 5897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, E. (1988). The Carolinian cane as a navigation instrument. Pacific Island Focus, 1, 14–33. [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel, M. (2013). Angry white men: American masculinity at the end of an era. Nation Books. [Google Scholar]

- Kokka, K. (2018). Healing-Informed social justice mathematics: Promoting students’ sociopolitical consciousness and well-being in mathematics class. Urban Education, 54(9), 1179–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokka, K. (2020). Social justice pedagogy for whom? Developing privileged students’ critical mathematics consciousness. The Urban Review, 52(4), 778–803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokka, K., & Chao, T. (2023). ‘How I show up for Brown and Black students’: Asian American male mathematics teachers seeking solidarity. In Men educators of color in US public schools and abroad (pp. 152–173). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Ladson-Billings, G. (2018). But that’s just good teaching! In Thinking about schools (pp. 107–116). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladson-Billings, G. (2021). Just what is critical race theory and what’s it doing in a nice field like education? In Critical race theory in education (pp. 9–26). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larnell, G. V., Bullock, E. C., & Jett, C. C. (2016). Rethinking teaching and learning mathematics for social justice from a critical race perspective. Journal of Education, 196(1), 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence-Lightfoot, S. (1983). The good high school: Portraits of character and culture (Vol. 5134). Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence-Lightfoot, S. (2005). Reflections on portraiture: A dialogue between art and science. Qualitative Inquiry, 11(1), 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence-Lightfoot, S., & Davis, J. H. (2002). The art and science of portraiture. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Lerman, S. (2000). The social turn in mathematics education research. Multiple Perspectives on Mathematics Teaching and Learning, 1, 19–44. [Google Scholar]

- Lerman, S. (2001). A review of research perspectives on mathematics teacher education. In Making sense of mathematics teacher education (pp. 33–52). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Love, B. L. (2019). We want to do more than survive: Abolitionist teaching and the pursuit of educational freedom. Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, D. B. (2013). Race, racial projects, and mathematics education. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education, 44(1), 316–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merriam, S. B. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applications in education. revised and expanded from “Case study research in education”. Jossey-Bass Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Moses, R., & Cobb, C. E. (2002). Radical equations: Civil rights from Mississippi to the Algebra Project. Beacon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nicol, C., Knijnik, G., Peng, A., Cherinda, M., & Bose, A. (Eds.). (2024). Ethnomathematics and mathematics education: International perspectives in times of local and global change. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Oluo, I. (2020). Mediocre: The dangerous legacy of white male America. Seal Press. [Google Scholar]

- Paris, D. (2017). On culturally sustaining teachers. In Equity by design: Midwest & plains equity. Assistance Center (MAP EAC). [Google Scholar]

- Phipps, A. (2021). White tears, white rage: Victimhood and (as) violence in mainstream feminism (Version 2). University of Sussex. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10779/uos.23477795.v2 (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Rezvi, S. K. (2025). Towards a theory of complex mathematical personhood: Math teachers of color in the workplace [Doctoral dissertation, University of Illinois at Chicago]. [Google Scholar]

- Rosa, M., Shirley, L., Gavarrete, M. E., & Alangui, W. V. (Eds.). (2017). Ethnomathematics and its diverse approaches for mathematics education. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenholtz, S. J. (1985). Effective schools: Interpreting the evidence. American journal of Education, 93(3), 352–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, D. A., & Morehouse, L. (2011). Teaching’s conscientious objectors: Principled leavers of high-poverty schools. Teachers College Record, 113(12), 2670–2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, B. S., & de Sousa Santos, B. (2007). Beyond abyssal thinking: From global lines to ecologies of knowledges. Review (Fernand Braudel Center), 30(1), 45–89. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40241677 (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Scafidi, B., Sjoquist, D. L., & Stinebrickner, T. R. (2007). Race, poverty, and teacher mobility. Economics of Education Review, 26(2), 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sfard, A., & Prusak, A. (2005). Telling identities: In search of an analytic tool for investigating learning as a culturally shaped activity. Educational Researcher, 34(4), 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons-Duffin, S., & Stone, W. (2025, January 31). Trump administration purges websites across federal health agencies. NPR. Available online: https://www.npr.org/sections/shots-health-news/2025/01/31/nx-s1-5282274/trump-administration-purges-health-websites:contentReference[oaicite:3]{index=3} (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Su, F. (2020). Mathematics for human flourishing. Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sutcher, L., Darling-Hammond, L., & Carver-Thomas, D. (2016). A coming crisis in teaching? Teacher supply, demand, and shortages in the US. Learning Policy Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Trask, H. K. (1991). Lovely hula hands: Corporate tourism and the prostitution of Hawaiian culture. Contours, 5(1), 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Treisman, R. (2025, March 18). Alien Enemies Act: The 1798 law is Trump’s new deportation tool. NPR. Available online: https://www.npr.org/2025/03/18/nx-s1-5331857/alien-enemies-act-trump-deportations (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Trinder, V. F., & Larnell, G. V. (2015, June 21–26). Toward a decolonizing pedagogical perspective for mathematics teacher education. Eighth International Mathematics Education and Society Conference (p. 219), Portland, OR, USA. Available online: https://mescommunity.info/MES8ProceedingsVol1.pdf#page=219 (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Tuck, E. (2009). Suspending damage: A letter to communities. Harvard Educational Review, 79(3), 409–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuhiwai Smith, L. (2012). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples. Bloomsbury Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Winkler-Morey, A. (2010). The war on history: Defending ethnic studies. The Black Scholar, 40(4), 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, C., & Otis, B. M. (2019). Mathematics for whom: Reframing and humanizing mathematics. Occasional Paper Series, 2019(41), 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, C., Rezvi, S., Martinez, R., & Shirude, S. (2021). Radical love as praxis: Ethnic studies and teaching mathematics for collective liberation. Journal of Urban Mathematics Education, 14(1), 71–95. Available online: https://journals.tdl.org/jume (accessed on 12 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods (Vol. 5). Sage. [Google Scholar]

| CMP 1|Remembrance and Forgetting: CMP 1 means that people remember and forget their mathematical experiences, they flow in and out of different identity locations in their personal and professional lives. |

| CMP 2|Harm and Joy: CMP 2 means that people might experience harm in mathematical spaces but can also potentially experience transformation, joy, and liberation. This is not binary. The way they suffer might reproduce further harm or other sites of possibility. This is not a binary either—it is possible that both might occur concurrently. |

| CMP 3|Socio-Historical and Socio-Cultural Navigations: CMP 3 means that people might experience mathematics classroom spaces as a cross-hatched weaving where the historical exclusionary practices of mathematics are enmeshed when viewed within the current manifestations of White supremacy, patriarchy, colonialism, transphobia, racism, misogyny, sexism, ableism and other forms of exploitation and oppression towards marginalized people. |

| CMP 4|Learning and (Un)Learning: CMP means that people might experience mathematics as a straightforward process and simultaneously a subtle reality where there is the possibility to (un)learn, transform, reject, liberate, and alchemize. The latter can be experienced unconsciously, without acute awareness until other actions bring that to the forefront. |

| Unit Title | Examining Indigenous Sustainable Food Practices |

| Developed by: | Kahiau and School Community |

| Suggested Course/Grade Level | MS Mathematics |

| Mana’o Nui/Big Idea: | A firm foundation in my identity sets the stage for future success. [What is] required for thriving industries and economies in the land? |

| Essential Question | Who am I and what role can I play as the lāhui [Hawaiian nation] seeks to reestablish kuapapa nui [the genealogy of Great Kaua‘i]? |

| Hākilo (Process Look Fors): |

|

| Goal | To convince audience members of the effectiveness of canoe plants as a means of bolstering Food Security in Hawai’i. |

| Situation | Currently 90% of Hawaiʻi’s food comes from external sources, which is not a sustainable practice. |

| Products | Students will participate in a Socratic seminar in which they use data gathered through the lens of their core classes to argue for the native plant that they believe could best be leveraged by our local communities to improve Hawaii’s Food Security. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rezvi, S.K. A Portrait of a Native Hawaiian Ethnomathematics Educator. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1445. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111445

Rezvi SK. A Portrait of a Native Hawaiian Ethnomathematics Educator. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(11):1445. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111445

Chicago/Turabian StyleRezvi, Sara Kanwal. 2025. "A Portrait of a Native Hawaiian Ethnomathematics Educator" Education Sciences 15, no. 11: 1445. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111445

APA StyleRezvi, S. K. (2025). A Portrait of a Native Hawaiian Ethnomathematics Educator. Education Sciences, 15(11), 1445. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15111445