1. Introduction

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental condition characterized by difficulties in communication and social interaction, along with restricted or repetitive patterns of behavior, interests, and activities (

APA, 2013;

Purpura et al., 2022). It presents substantial heterogeneity: some individuals demonstrate high functionality and outstanding specific abilities, while others require extensive daily life support (

Genovese & Butler, 2020;

Mottron & Bzdok, 2020). This variability has led to its conceptualization as a spectrum, reflecting the diversity of profiles and the complexity of its educational and clinical care (

Lord et al., 2022).

The prevalence of ASD has increased markedly over the past decade. In Spain, it represents around 1% of students in non-university stages and nearly 30% of those with special educational needs (

Plaza, 2025). Internationally, approximately one in 31 eight-year-old children meets diagnostic criteria (

Shaw et al., 2025), a growing trend also observed in other countries (

Talantseva et al., 2023). Contributing factors include the broadening of diagnostic criteria, greater awareness, early detection, and increased visibility of previously underdiagnosed profiles—such as female autism (

Rippon, 2024)—alongside biological and environmental influences (

Love et al., 2024).

This increase has a direct impact on the educational system, with a growing presence of students with ASD from early childhood through university, particularly among those with more autonomous functional profiles (

Anderson et al., 2019). This scenario poses challenges in terms of inclusion, support, and institutional adaptation. Within this context, teacher preparation becomes crucial, understood as the set of knowledge, skills, and socio-emotional resources that enable educators to recognize needs, design tailored supports, and create equitable learning environments.

1.1. Teachers’ Professional Competence in the Inclusion of Students with ASD

According to the model of professional teaching competence proposed by

Baumert and Kunter (

2013), this construct is understood as multidimensional, encompassing several interrelated components: domain-specific professional knowledge, pedagogical attitudes, motivation, and self-regulation. This theoretical framework, widely supported by empirical evidence across various educational contexts, has served as a key reference for research focused on teaching quality and the implementation of inclusive educational practices.

In the context of educational inclusion for students with ASD, recent studies (

Russell et al., 2023;

Wittwer et al., 2024) have shown that teachers’ inclusive competence depends on multiple interconnected factors, including specialized training, conceptual and applied knowledge of ASD, prior experience with this student population, and socio-emotional competencies (such as attitudes and self-efficacy). These factors significantly influence teachers’ readiness for inclusion and, consequently, the quality of educational responses. Moreover, the practical implementation of observable inclusive strategies in the classroom represents the pedagogical manifestation of such competencies, linking teachers’ personal resources with students’ effective participation (

Bolourian et al., 2022;

Gal et al., 2025).

In this context, the frameworks developed by the Autism Education Trust (AET) constitute one of the most recent and specific references for guiding the educational support of students with ASD. In their current formulation, outlined in the School Competency Framework

AET (

2022) and the Schools Standards Framework (

AET, 2023), professional competence is organized around four integrated areas: Learning & Development, Positive & Effective Relationships, Enabling Environments, and Personalised Support. These areas can be conceptually linked to the general components described by

Baumert and Kunter (

2013), as they translate them into the realm of inclusion and diversity. In addition, they emphasize the need for ongoing professional development, the cultivation of socio-emotional competencies, and the creation of accessible and inclusive environments.

Nevertheless, despite its relevance, the AET framework is presented as a reference model and formative guide, rather than as a psychometric instrument for standardized assessment. Consequently, the questionnaire developed in this study provides added value by operationalizing these competencies in an empirically validated format, contextualized to the Spanish educational system. Its design was grounded in previous evidence on inclusive teaching competence (

Baumert & Kunter, 2013;

Russell et al., 2023;

Wittwer et al., 2024) and in studies emphasizing the importance of specialized training, theoretical and applied knowledge, direct experience with students with ASD, and socio-emotional competencies, as well as the essential role of inclusive classroom practices in fostering participation and learning (

AET, 2022,

2023;

Bolourian et al., 2022;

Gal et al., 2025).

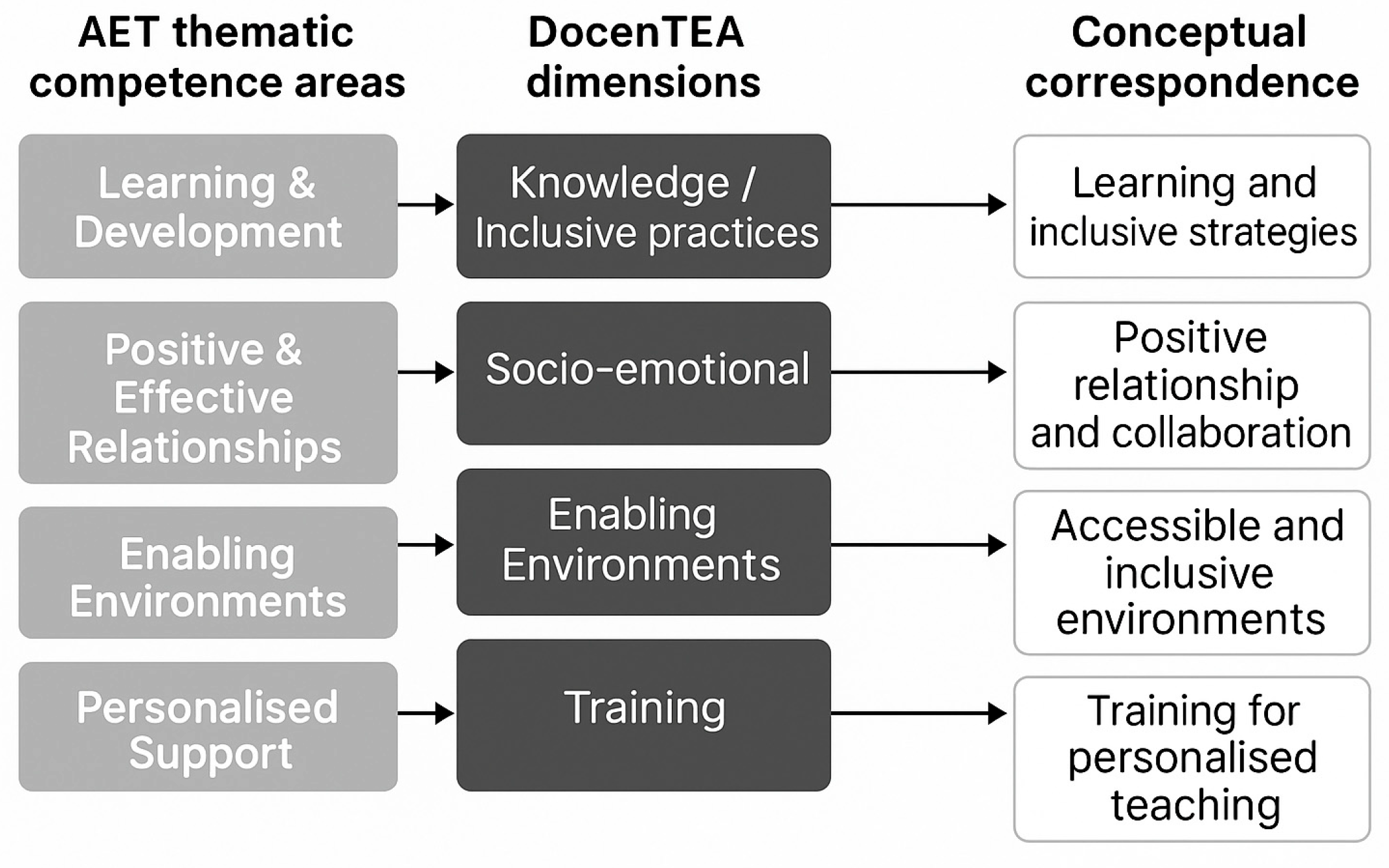

Building on this framework, the

DocenTEA questionnaire was structured around five interrelated dimensions—Training, Knowledge, Experience, Socio-emotional Competence, and Inclusive Pedagogical Practices—whose correspondence with the AET areas is summarized in

Figure 1. It is worth noting that, in this correspondence, some AET areas are linked to more than one teaching dimension, reflecting the conceptual intersection and the complementarity of these approaches.

The following section presents a concise overview of the five dimensions structuring the DocenTEA questionnaire, with the aim of clarifying their conceptual foundations and facilitating understanding of the instrument’s development process.

1.1.1. Training Dimension

Teacher training, both initial and ongoing, constitutes a decisive factor in preparing educators to respond effectively to the needs of students with ASD. It is not limited to the acquisition of theoretical knowledge but also encompasses the development of practical competencies, critical reflection skills, and awareness of diversity—elements that enable the translation of conceptual understanding into appropriate pedagogical practices.

Recent studies (

Russell et al., 2023;

Wittwer et al., 2024) have shown that specialized training in ASD is associated with higher levels of knowledge, self-efficacy, and positive disposition toward inclusion, directly impacting the quality of pedagogical responses. This effect has been observed across diverse educational and cultural contexts, confirming that training is a robust predictor of inclusive competence.

Moreover, previous research (

Gómez-Marí et al., 2021;

Wittwer et al., 2024) has indicated that teachers who receive specialized preparation demonstrate a greater capacity to interpret the behaviors of students with ASD and to implement evidence-based supports, such as differentiated instruction, the use of visual aids, or adapted communication strategies.

However, other studies (

Lee & Abdullah, 2024) highlight that initial training related to ASD remains fragmented and limited, creating a gap between classroom demands and the actual preparedness of teachers at the start of their careers. This training deficit is further exacerbated by the lack of systematic, contextually relevant ongoing professional development programs, hindering the consolidation of inclusive competencies over time.

Within the current framework of the

AET (

2022,

2023), the training dimension is primarily associated with the thematic area of Personalised Support. This approach underscores the need for teachers to have sustained opportunities for professional development that enable them to adapt their practice to the specific needs of students with ASD. From this perspective, training cannot be regarded as a one-off event but rather as a structural and ongoing process, supported by institutional commitment and an inclusive leadership culture that ensures coherent and enduring educational practices (

Padilla Quero & Infante Cañete, 2022).

1.1.2. Knowledge Dimension

Teacher knowledge of ASD constitutes a central component of inclusive professional competence, providing the conceptual and practical foundations necessary to understand students’ characteristics, needs, and potentials. This knowledge encompasses both conceptual aspects—diagnostic criteria, core traits, and variability in spectrum expression—and their pedagogical application, that is, the ability to interpret specific behaviors and plan appropriately tailored educational responses (

APA, 2013;

Lord et al., 2022).

Several authors (

Gómez-Marí et al., 2021;

Russell et al., 2023) have shown that a higher level of knowledge promotes more accurate and context-sensitive interpretations of behaviors, reduces stigmatizing attitudes, and encourages the implementation of pedagogical strategies adapted to the individual needs of students with ASD. Such strategies include incorporating visual supports, offering choice in tasks, and adapting communication methods, which have been shown to foster more accessible and inclusive learning environments (

Wittwer et al., 2024).

Research has demonstrated that possessing up-to-date, evidence-based knowledge about ASD enhances the quality of educational responses and contributes to generating more realistic expectations for students (

Gómez-Marí et al., 2021;

Russell et al., 2023). This knowledge enables teachers to recognize core characteristics—for example, patterns of social communication and restricted or repetitive interests—and understand how these influence participation and learning.

However, studies also warn that knowledge deficits remain common among teachers without specialized training or direct experience with this student population, limiting their ability to plan appropriate supports and potentially leading to misunderstandings or lowered expectations (

Lee & Abdullah, 2024).

Wittwer et al. (

2024) observed in a study of 887 teachers in Germany, that despite of the positive attitudes toward inclusion, there were notable gaps persisted in ASD knowledge, particularly among those who had not received formal training. Consistently,

Lee and Abdullah (

2024) concluded that greater knowledge is associated with more favorable attitudes, although it does not always translate into higher perceived self-efficacy.

In the current formulation of the

AET (

2022,

2023), the knowledge dimension is primarily linked to the thematic area Learning & Development. This approach emphasizes the need for teachers to possess solid and up-to-date knowledge of ASD, enabling them to accurately interpret diverse learning profiles and design strategies personalised to individual needs. This articulation supports the idea that teacher knowledge is an essential—but not only—prerequisite for ensuring coherent but also for effective inclusive practices.

1.1.3. Experience Dimension

Several studies have shown that prior experience with students with ASD is a determining factor in the development of inclusive teaching competence, as it provides real opportunities to apply theoretical knowledge, test perceptions, and adjust pedagogical strategies (

Gómez-Marí et al., 2022;

Russell et al., 2023;

Wittwer et al., 2024). This contact can occur in everyday teaching practice, through supervised internships, collaboration with specialized support teams, or participation in inclusive educational projects.

Recent research (

Wittwer et al., 2024) has revealed that direct experience fosters a deeper understanding of the heterogeneity of the spectrum and allows teachers to better understand student behaviors, differentiating between difficulties intrinsic to ASD and contextual factors. This explains a greater ability to adjust pedagogical strategies and support classroom participation.

Regarding inclusive attitudes findings are mixed: some studies report that direct contact is associated with more positive attitudes and a greater willingness to implement adaptations (

Russell et al., 2023), while others warn that experience, in the absence of training and institutional support, can lead to frustration or lower teacher self-efficacy (

Chung et al., 2015).

Despite these differences, most studies agree that practical experience reinforces both knowledge and teacher self-efficacy, promoting a more consistent implementation of inclusive strategies. Learning that occurs through direct interaction with students and reflection on practice, it has been identified as a key pathway for consolidating inclusive competencies throughout a professional career (

Alassaf, 2025;

Gómez-Marí et al., 2022).

In the current frameworks of the

AET (

2022,

2023), this dimension is primarily linked to the thematic area of Enabling Environments. This approach emphasizes that teacher experience with students with ASD not only facilitates the acquisition of technical skills to meet their needs but also enhances collaborative work with other professionals, families, and the students themselves. Therefore, practical experience strengthens teaching competence by connecting conceptual knowledge with direct experience in real educational contexts.

1.1.4. Socio-Emotional Dimension

The socio-emotional dimension, encompassing empathy, inclusive attitudes, and teachers’ ability to manage emotions in diverse educational contexts, is recognized as a key component of teaching competence for the inclusion of students with ASD (

Calandri et al., 2025;

Han & Cumming, 2024). This component goes beyond affective disposition toward students; it also involves understanding that certain behaviors are linked to particular ways of processing information and the environment, as well as the ability to foster a positive classroom climate and manage situations of anxiety, frustration, or challenging behaviors (

Russell et al., 2023).

Recent research has shown that teachers’ socio-emotional competence—including empathy, self-regulation, and socio-emotional management—predicts the quality of school climate, teacher–student relationships, and the effectiveness of inclusive practices (

Calandri et al., 2025;

Dignath et al., 2022;

Johnson et al., 2021). Complementarily, empathy, emotional self-regulation, and the creation of a safe classroom environment have been shown to mediate the relationship between training received and the implementation of inclusive practices (

Han & Cumming, 2024).

Findings from

Wittwer et al. (

2024) reinforce this perspective by showing that perceived self-efficacy constitutes a critical factor in teachers’ preparedness to apply inclusive strategies, distinguishing it from mere conceptual knowledge. This conclusion aligns with the systematic review by

Russell et al. (

2023), which explicitly differentiates between technical knowledge and attitudinal disposition in shaping inclusive competence.

Within the

AET (

2022,

2023), this dimension is primarily linked to the thematic area Positive & Effective Relationships, which emphasizes the need for teachers to combine interpersonal sensitivity with the ability to work collaboratively with students, families, and teaching teams. In this way, socio-emotional competence not only contributes to creating a positive and inclusive classroom climate but also strengthens teachers’ ability to respond sensitively and appropriately to the needs of students with ASD.

1.1.5. Inclusive Pedagogical Practices Dimension

The Inclusive Pedagogical Practices dimension refers to the observable strategies that teachers employ to promote the participation, learning, and socio-emotional well-being of students with ASD in mainstream classrooms. This component translates knowledge, experience, and inclusive attitudes into concrete actions, serving as the bridge between teachers’ personal resources and effective educational responses.

Recent research (

Bolourian et al., 2022;

Gal et al., 2025;

Han & Cumming, 2024) has highlighted that the most effective inclusive practices for students with ASD include adapting instruction to individual needs, designing personalized assessments, incorporating students’ interests as motivational resources, managing interpersonal conflicts from an inclusive perspective, and implementing cooperative learning activities that encourage the participation of the entire class. These practices enhance both curricular accessibility and social participation for students with ASD, reducing barriers to learning and peer interaction.

In addition, several studies (

Petersson-Bloom & Holmqvist, 2022;

Shaw et al., 2025) have emphasized that the use of visual support, differentiated instruction, personalized assessment, and collaboration with families and specialized teams are key resources for supporting the participation and learning of students with ASD in inclusive settings. These practices allow educational responses to be tailored to diverse student profiles, strengthening both equity and pedagogical effectiveness. However, evidence also indicates that implementation is uneven: while some teachers apply these practices consistently, in other cases they depend on personal initiative or the availability of institutional resources and support (

Alassaf, 2025;

Gal et al., 2025).

Overall, this evidence supports the idea that teachers’ inclusive competence is not limited to positive attitudes or conceptual knowledge, but must manifest in concrete, systematic, and sustainable practices that facilitate the active participation of students with ASD in both academic and social classroom dynamics.

In the current frameworks of the

AET (

2022,

2023), this dimension is primarily linked to the thematic areas Learning & Development and Enabling Environments. Both emphasize that inclusion depends not only on individual teacher initiative but also on a school environment that fosters collaborative work, provides adequate supports, and sustains an institutional culture oriented toward equity.

Thus, inclusive pedagogical practices constitute the most tangible expression of professional inclusive competence, demonstrating how teachers can explain their knowledge, experience, and dispositions into actual pedagogical actions that promote meaningful participation and learning for students with ASD.

In summary, the five dimensions described—training, knowledge, experience, socio-emotional, and inclusive pedagogical practices—provide a coherent, multidimensional theoretical framework for understanding teachers’ inclusive competence regarding students with ASD, in line with

Baumert and Kunter (

2013) and the current guidelines of the

AET (

2022,

2023). This model conceptually underpins the content of the

DocenTEA questionnaire and highlights that genuine inclusion requires concrete and sustainable pedagogical actions that enable active participation and meaningful learning for students with ASD.

1.2. Tools for Analyzing Teachers’ Attitudes and Knowledge About ASD: A Contextualized Review

Over the past decade, interest has grown in assessing teachers’ positioning regarding the inclusion of students with ASD. However, most available instruments have focused in a fragmented manner on isolated dimensions—attitudes, self-efficacy, or knowledge—without providing a comprehensive view of inclusive teaching competence. Thus, while some scales aim to measure beliefs and dispositions (e.g., the Autism Attitude Scale for Teachers—AAST,

Olley et al., 1981), others have prioritized perceived self-efficacy (e.g., the Autism Self-Efficacy Scale for Teachers—ASSET,

Ruble et al., 2013) or conceptual knowledge of autism (e.g., AKSS,

Derguy et al., 2022).

Although these tools have demonstrated adequate psychometric properties, they present notable limitations. On the one hand, they often address dimensions separately, making it difficult to capture the interaction between cognitive, socio-emotional, and practical factors in teacher preparation (

Gómez-Marí et al., 2021;

Russell et al., 2023). On the other hand, they lack a systematic development that simultaneously integrates training received, prior experience, and the implementation of inclusive classroom practices—dimensions that the literature identifies as critical for ensuring the inclusion of students with ASD (

Han & Cumming, 2024;

Wittwer et al., 2024).

More recent proposals, such as adaptations of the AAST and the ASK-Q in African contexts (

Tsegaye et al., 2025), represent relevant advances in terms of cross-cultural validity. Nevertheless, they still do not incorporate indicators of the actual application of inclusive pedagogical practices, reducing their utility for diagnosing training needs in diverse educational contexts.

Accumulated evidence also suggests that variables such as initial and ongoing training, access to resources, and prior experience with students with ASD influence teachers’ knowledge, attitudes, and self-efficacy (

Chung et al., 2015;

Johnson et al., 2021). However, to date, no instruments integrate these dimensions within a coherent theoretical and empirical framework.

In this context, the design and validation of the DocenTEA questionnaire is presented, conceived to assess in an integrated manner five interrelated dimensions of inclusive teaching competence: training, knowledge, experience, socio-emotional competence, and inclusive pedagogical practices. Unlike previous instruments, DocenTEA does not limit itself to measuring attitudes or knowledge in isolation but links them to accumulated experience and the application of inclusive strategies in actual classroom practice. In this way, it constitutes an innovative and contextualized tool that advances both research and the identification of specific teacher training needs across educational levels.

Accordingly, the main objective of the present study was to design and validate the DocenTEA questionnaire, intended to assess teachers’ competencies and attitudes at different educational levels with students with ASD. To achieve this, a rigorous process was followed, including content validation through expert judgment, pilot testing of the instrument, and construct validation via exploratory factor analysis. The identification of a five-dimensional structure aims to provide a robust and contextualized tool that contributes both to research and to the detection of teacher training needs regarding the inclusion of students with ASD.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This study adopts a quantitative and instrumental approach, with the primary objective of designing and validating a questionnaire aimed at assessing teachers’ competencies and attitudes toward the inclusion of students with ASD across different educational levels. The validation process was carried out in successive phases, which included: (a) the initial construction of the instrument, (b) the evaluation of content validity through expert judgment, (c) the analysis of internal reliability using Aiken’s V, and (d) construct validation through exploratory factor analysis (EFA), conducted with SPSS software (version 25) based on data collected in a pilot application.

Prior to the development of the questionnaire, all necessary institutional authorizations were obtained. The study was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of CEU San Pablo University (code CECO: 401.998), in accordance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and with European and national regulations governing research involving human participants.

Furthermore, the project was funded by the CEU San Pablo University Research Project Program, within the framework of institutional projects (reference MPF 124GG/1), which facilitated both the development of the instrument and the pilot application for its empirical validation.

2.2. Participants

The study involved two groups of participants: in-service teachers and a panel of experts.

In-service teachers: The sample consisted of 270 in-service teachers, selected through non-probability incidental (convenience) sampling, representing different educational levels: early childhood, primary, secondary, vocational training, and higher education. Regarding sociodemographic characteristics (see

Table 1), the sample showed a predominance of women (75.9%) compared to men (23%), as well as a concentration in the age range of 41–50 years (34.4%), followed by the groups aged 36–40 years (15.6%) and 51–55 years (11.5%), while the extreme ranges (20–25 and 66–70 years) presented marginal frequencies.

Regarding academic background, most teachers held a university degree, and a significant proportion had completed postgraduate studies, including master’s or doctoral degrees. Teaching experience was also diverse, with the largest representation in the 21–30 years of professional experience group. In terms of the educational level taught, primary and secondary stages were the most represented, whereas vocational training and higher education showed lower participation. It should be noted that this variable was collected as a multiple-response question, as many teachers work across more than one educational level. For this reason, the sum of the frequencies by level (380) exceeds the total sample size (N

n= 270), reflecting the multi-stage nature of teaching practice. The academic and professional profile of the participants is presented in

Table A1 (see

Appendix A).

- 2.

Expert panel: For content validation, a panel of five expert judges was formed, selected based on their experience in educational inclusion and working with students with ASD. Efforts were made to ensure diversity in experience and representation across professional fields, including university professors in education and psychology, school counselors, and non-university teachers with specialized training in autism. The group was balanced in terms of sex and provided a multidimensional perspective on the appropriateness, clarity, and relevance of the items (see

Table 2 for their demographic and professional characteristics).

2.3. Instrument

The

DocenTEA questionnaire consists of 25 items distributed across five theoretical dimensions: Training (items 1–5), Knowledge (items 6–10), Experience (items 11–15), Socio-emotional (items 16–20), and Inclusive Pedagogical Practices (items 21–25).

Appendix A (

Table A2) presents the items of the questionnaire, organized according to their respective dimension. Responses were recorded using a five-point Likert scale, with values ranging from 0 to 4 [0 = Never, 1 = Almost never, 2 = Sometimes, 3 = Almost always, and 4 = Always]. Scores, both by dimension and total, can be obtained by directly summing the values assigned to each item, with higher scores indicating a greater level of the characteristic being assessed.

2.4. Procedure

The final version of the DocenTEA questionnaire, after content validation, was distributed digitally between (September/2024–December/2024) using a combined strategy to ensure broad and diverse participation. The dissemination was carried out through professional teaching associations, regional educational networks, and direct e-mail invitations to schools.

To minimize response bias and preserve anonymity, no personal identifiers were collected. Participants could withdraw at any time without consequences. The survey was open for responses during a period of 4 months. Data were collected securely through Google Forms and stored on encrypted servers accessible only to the research team.

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Committee (CECO: 401.998) and conducted in accordance with national and international ethical standards for research involving human participants. (

World Medical Association, 2013).

A total of 270 teachers completed the questionnaire in full and were included in the analyses. The subsequent sections report the validation procedures: first, the content validity assessment through expert judgment (

Section 2.5), followed by the construct validity and reliability analyses based on the study sample (

Section 2.6).

The instrument was developed based on a comprehensive theoretical review and the consensus of a panel of specialists composed of professionals in education, psychology, and biomedical sciences. The formulation of the items was grounded in the literature on professional teaching competence in inclusive contexts, with particular attention to the inclusion of students with ASD. As reference frameworks, Baumert and Kunter’s model, which conceives teaching competence as a multidimensional construct encompassing cognitive, attitudinal, and motivational components, was considered, along with the current frameworks of

AET (

2022,

2023), which operationalize these competencies from an inclusive perspective.

Furthermore, recent evidence emphasizing the interaction between knowledge, attitudes, and self-efficacy in teachers’ disposition toward inclusion (

Russell et al., 2023;

Wittwer et al., 2024) was integrated, as well as research highlighting the value of observable pedagogical practices as concrete manifestations of these competencies (

Aiello & Sharma, 2018). Each item was designed to clearly represent one of the proposed dimensions, ensuring conceptual relevance, linguistic clarity, and appropriateness for the Spanish educational context.

Following its construction, the questionnaire underwent a content validation process through expert judgment and Aiken’s V coefficient (acceptance threshold ≥ 0.70), as described in

Section 2.5. After incorporating the revisions suggested by the expert panel, the final version of the instrument was distributed digitally through social media, professional associations, and direct contact with educational institutions.

2.5. Content Validation

Once the preliminary version of the

DocenTEA questionnaire was developed, content validation was carried out using the expert judgment technique (

Escobar-Pérez & Cuervo-Martínez, 2008), aiming to ensure the adequacy, clarity, and relevance of the included items. This procedure is particularly useful for determining whether the proposed items accurately reflect the theoretical constructs they intend to measure.

The selection of experts aimed to ensure a representative and contextually grounded perspective on the study object. Although all participants were specialists in the field, priority was given to their teaching experience across different levels of the educational system. The panel was composed of professionals from academic and educational backgrounds, including university professors specializing in education and psychology, school counselors, and non-university teachers with specific training in autism.

Each expert received an evaluation guide and a rubric containing the items classified into two dimensions. They were asked to assess each item based on three criteria (

Aiken, 1985):

Clarity: The degree of linguistic precision and comprehensibility of each item was evaluated, with particular attention to the absence of ambiguity or confusing wording.

Relevance: The appropriateness and consistency of the item content were analysed in relation to the theoretical dimension it aimed to measure.

Significance: The importance of each item within the overall instrument was assessed, considering its utility for measuring valid constructs.

To facilitate evaluation, a five-point ordinal scale was designed: optimal, high, moderate, low, and none. These qualitative ratings were subsequently converted into numerical values (5 to 1) for quantitative analysis.

Furthermore, the formulation of the questionnaire items was based on a comprehensive review of the literature on professional teaching competence in inclusive contexts, with a particular emphasis on the inclusion of students with ASD. Well-established theoretical frameworks were used as references, particularly the model proposed by

Baumert and Kunter (

2013), which conceptualizes teaching competence as a multidimensional construct encompassing cognitive, attitudinal, and motivational components.

Recent studies highlighting the interaction between knowledge, attitudes, and self-efficacy in inclusive teaching (

Russell et al., 2023;

Wittwer et al., 2024) were also considered, as well as research emphasizing the importance of pedagogical strategies as observable manifestations of inclusive disposition (

Aiello & Sharma, 2018). Each item was designed to clearly and specifically represent one of the five dimensions of the instrument, with special attention to conceptual relevance, linguistic clarity, and appropriateness for the Spanish educational context.

In addition, a quantitative analysis of the expert evaluations was conducted using Aiken’s V coefficient (

Penfield & Giacobbi, 2004), which estimates the degree of consensus among experts regarding the content validity of the items. The qualitative ratings were first converted to a numerical scale (1 = none, 5 = optimal).

The procedure was then applied accordingly. A threshold value of 0.70 or higher was established as the acceptance criterion. This value indicates substantial agreement among the experts and serves as evidence that the item in question is clear, pertinent, and/or relevant within the framework of the assessment instrument. The results of the expert evaluation of the items’ clarity, relevance, and significance are summarized in

Table 3.

As shown in

Table 3, all items met the acceptance threshold except for items 8 and 9 in the clarity parameter. These two items were subsequently revised to improve linguistic precision and reduce potential ambiguities before proceeding with the pilot administration of the questionnaire. Afterward, a qualitative analysis of the evaluations provided by the experts was conducted. The content of these evaluations was essential for making additional adjustments to the wording of the items. At this stage, subtle but strategic modifications were introduced to improve the coherence, appropriateness, and terminological accuracy of the statements. Following the modifications suggested by the expert panel, the questionnaire was piloted with the 270 participating teachers. The data collected during this phase enabled the subsequent psychometric analyses to assess the instrument’s construct validity, internal reliability, and overall consistency, the results of which are presented in the following section.

2.6. Construct Validity Analysis

To evaluate the construct validity of the DocenTEA questionnaire, we conducted EFA using the Unweighted Least Squares (ULS) extraction method and Promax oblique rotation with Kaiser normalization, given the expected correlations among factors. Items were retained based on theoretical coherence, factor loadings ≥ 0.30, and communalities ≥ 0.20. The analysis yielded a five-factor solution: Inclusive Practices, Training, Knowledge, Experience and Socio-emotional explaining 60.43% of the total variance. Reliability was assessed for each factor using Cronbach’s α and McDonald’s ω, both meeting or exceeding the recommended 0.70 threshold. Data processing and analysis were carried out using the statistical software SPSS (version 25).

First, the suitability of applying EFA was evaluated using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure and Bartlett’s test of sphericity. The KMO value obtained was 0.898, which, according to conventional criteria (

Kaiser, 1970), indicates excellent sample adequacy (values ≥ 0.80). Additionally, Bartlett’s test of sphericity (

Bartlett, 1951) yielded a statistically significant result (χ

2 = 3082.845; df = 300;

p < 0.001), rejecting the null hypothesis that the correlation matrix is an identity matrix and confirming sufficient correlations among variables to justify the application of dimensionality reduction techniques. Taken together, these results confirm that the data were appropriate for conducting an EFA.

Once the appropriateness of the analysis was confirmed, the EFA was performed. To select the most suitable extraction method, the normality assumption of the observed variables (items) was assessed using skewness and kurtosis statistics, following the criteria of

Ferrando and Anguiano-Carrasco (

2010) and

Muthén and Kaplan (

1985,

1992), who consider values within the ±1 range as indicative of univariate normality. As some items exceeded this threshold (see

Table 4), a robust extraction method against non-normality was employed: Unweighted Least Squares (ULS). This procedure allows for valid estimates without requiring the assumption of normal distribution (

Finney & DiStefano, 2013), ensuring the robustness of the results obtained in the factor analysis.

Regarding the rotation procedure, since the factors were expected to be correlated, an oblique rotation was applied, specifically the Promax method with Kaiser normalization. By adjusting factor loadings prior to rotation, this method balances the influence of all items, improves the stability of the factorial solution, and facilitates the interpretation of the underlying factor structure by simplifying item loadings while maintaining the possibility of correlations between factors (

García Jiménez et al., 2000).

Factor retention criteria were based on eigenvalues greater than 1, according to

Kaiser’s (

1960) criterion, and the theoretical interpretability of the resulting dimensions. Item retention criteria were based on factor loadings (λ ≥ 0.30), the absence of significant cross-loadings, consistency with the proposed theoretical dimension, and communality values (h

2 ≥ 0.20). Additionally, the impact of each item on the internal consistency of the scale was considered.

Finally, to assess the internal consistency of the scale, reliability analysis was conducted using

Cronbach’s (

1951) alpha coefficient along with

McDonald’s (

1999) omega, an estimator considered more accurate than Cronbach’s alpha, particularly in factorial structures with unequal item loadings, ensuring a robust evaluation of the questionnaire’s reliability. In both cases, values equal to or greater than 0.70 were considered acceptable (

Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994).

Furthermore, Cronbach’s alpha analysis allowed for the examination of not only the overall reliability of each factor but also the individual contribution of items through two key indicators: the corrected item–total correlation and the change in alpha coefficient when each item is deleted. The corrected item–total correlation evaluates the extent to which each item correlates with the total scale score, excluding the item itself from the calculation. Values above 0.30 indicate adequate item discrimination, whereas lower values suggest low consistency with the measured construct. Additionally, the analysis of the change in alpha deleting each item allows to identify whose removal would improve the overall reliability of the scale.

Although the criterion adopted for item retention was a factor loading of ≥0.30 (

Field, 2018), item 18 (λ = 0.269) was provisionally retained. This decision was justified by its conceptual relevance in representing teachers’ emotional self-regulation in situations of anxiety and frustration, a central component of the socio-emotional dimension. Moreover, the item showed a satisfactory corrected item–total correlation (r = 0.49), and its removal did not substantially improve the internal consistency of the socio-emotional factor (α = 0.76 vs. 0.73). Therefore, it was retained for future review and re-evaluation in confirmatory studies (CFA).

Together, these analyses allowed for verification of both the adequacy of the proposed factorial structure and the internal consistency of each dimension, providing robust evidence of the instrument’s validity and reliability.

4. Discussion

The results of this study provide preliminary evidence of the validity and reliability of the

DocenTEA questionnaire, designed to assess inclusive teaching competence in relation to students with ASD. Exploratory factor analysis confirmed a five-dimension structure—Inclusive Practices, Training, Knowledge, Experience and Socio-emotional—consistent with the professional competence model proposed by

Baumert and Kunter (

2013) and aligned with the current frameworks of the

AET (

2022,

2023). This dual convergence reinforces the conceptual relevance of the instrument, supports its alignment with international standards, and facilitates translating the results into practical guidance for teacher training, peer mentoring, and institutional planning.

Among the most notable findings is the central role of Inclusive Practices (Factor 1), the dimension that explained the largest proportion of variance and encompassed indicators of pedagogical adaptation, conflict management, and cooperative strategies. This result is consistent with previous studies identifying observable practice as the core of inclusive competence (

Bolourian et al., 2022;

Gal et al., 2025) and aligns with the AET’s Learning & Development area, which translates beliefs and knowledge into classroom actions.

Training (Factor 2) also emerged as a robust factor closely linked to Experience supporting the interdependence between continuous professional development and situated learning. This finding aligns with the AET, which positions professional development and school environments (Personalised Support and Enabling Environments) as structural levers for inclusion. Knowledge (factor 3) was identified as a distinct dimension, consistent with the AET’s Learning & Development area and evidence indicating that technical understanding of ASD does not always correlate with attitudes or self-efficacy (

Lee & Abdullah, 2024;

Russell et al., 2023). The Experience (factor 4) relates closely to the AET’s emphasis on Enabling Environments and reflective practice in real-world contexts. Finally, the Socio-emotional (factor 5) underscores the importance of empathy and self-regulation in building inclusive environments, consistent with the Positive & Effective Relationships area of current AET frameworks.

Regarding internal consistency, reliability indices met or approached the 0.70 benchmark across factors (F1 α = 0.86–0.89; F2 α = 0.81–0.85; F3 α = 0.65–0.75; F4 ≈ 0.70 after addressing item 14; F5 α = 0.76, ω = 0.69), which is considered adequate for an exploratory phase. Items with suboptimal performance (particularly items 14 and 18) will be refined in subsequent iterations. Item 14, initially worded in reverse, was not recoded but deliberately removed from the analysis to improve the reliability indices. This decision was taken consciously in the exploratory phase, and the item will be revised or rewritten for future iterations.

Likewise, item 18, which showed a low loading within factor 5 will be reworded (for example focusing on emotional self-regulation in specific situations) to improve conceptual fit. Regarding this item, although its factor loading was below the previously established threshold (λ = 0.269), it was retained at this exploratory stage due to its strong conceptual relevance in capturing teachers’ emotional self-regulation in situations of anxiety and frustration. In addition, it showed an acceptable corrected item–total correlation (r = 0.49), and its removal did not substantially increase the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the socio-emotional factor (α = 0.76 vs. 0.73). Consequently, it was decided to retain the item for future validation phases, during which its wording will be refined, and its performance re-evaluated through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). This decision reflects the intention to preserve the conceptual coverage of the socio-emotional dimension while continuing to improve the psychometric quality of the instrument.

Furthermore, McDonald’s omega reliability coefficient for Factor 5 (Socio-emotional) was 0.69, a value slightly below the recommended threshold of 0.70. This result is considered acceptable within an exploratory phase, particularly given the small number of items comprising the socio-emotional dimension and their conceptual relevance. Nevertheless, it is acknowledged as a minor limitation of the model, which should be addressed in future refinement and validation phases through the revision of item 18 and the potential inclusion of additional indicators to strengthen the internal consistency of the scale. In addition, Item 19, whose content overlaps with inclusive practices, will be explicitly tested in future confirmatory factor analyses for potential reassignment to factor 1 or for allowing residual correlation in order to ensure structural coherence.

Similarly, it is important to consider the cross-loading observed for item 11, which was theoretically conceived as part of the Experience dimension but showed a higher loading on Factor 2 (Training). This association suggests that teachers may perceive their professional experience as closely linked to their ongoing training, potentially reflecting how learning derived from teaching practice is reinterpreted as part of the broader formative process. This observation does not weaken the model; rather, it provides a valuable perspective for future revisions of the instrument, where it could be explored whether the interrelation between experience and training constitutes an emerging factor or whether the wording of the item requires adjustments to clarify its conceptual focus.

Despite these strengths, several limitations should be noted. The incidental sampling restricts the generalizability of the results, making it advisable to replicate the analysis with larger and more representative samples. The self-report nature may introduce social desirability or common-method biases, suggesting that future studies should be complemented with classroom observations or external reports. Furthermore, the cross-sectional design precludes the analysis of temporal stability and of the sensitivity of the instrument to changes resulting from training interventions; these issues should be addressed through longitudinal studies and criterion-related validity research.

In future research, it would be desirable to complement these efforts with stratified random sampling by region or educational level, in order to increase the representativeness of the findings. Following the promising results of the present exploratory factor analysis (EFA), the logical next step will be to conduct a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) on an independent sample, allowing the five-factor structure to be verified and providing model fit indices (CFI, RMSEA, SRMR), thereby reinforcing the robustness of the structural validity.

Furthermore, the suboptimal performance of items 14 and 18 highlights the need for conceptual review and refinement of their wording to improve psychometric discrimination. Given that some reliability indices were around 0.70, it would be advisable to expand the scale with additional, more complex items that better capture the intra-individual and contextual variability of teachers’ competencies.

Although the present study was conducted in Spain, future research should examine the linguistic and cultural adaptation of the instrument to ensure semantic and functional equivalence in other countries, with the aim of promoting the international comparability of results.

In summary, DocenTEA represents a significant methodological advance and a tool with clear practical potential for educational institutions. By integrating five interrelated dimensions into a single validated instrument, it enables a more comprehensive assessment of teacher preparedness and the identification of both strengths and training gaps in diverse educational contexts. Nevertheless, as an exploratory study, further validation in larger and more diverse samples will be necessary to consolidate its use as a reference instrument in both research and inclusive educational practice.

Building on these findings, the practical implications of this study are noteworthy. The

DocenTEA questionnaire allows for the identification of both teachers’ strengths and training needs and links the results to the competency areas described in current

AET (

2022,

2023) frameworks. For example, deficits in Learning & Development can guide the design of specific continuing professional development modules; low scores in the Inclusive Practices dimension indicate the need to reinforce visual supports, differentiation, or adapted assessment; combined profiles of training and experience can serve as a basis for implementing peer mentoring and learning strategies; and school-level results can inform leadership and school climate plans aligned with international standards. From an ethical perspective, the use of the instrument should focus on formative feedback and avoid any punitive application.

To date, available instruments have contributed valuably to the assessment of specific dimensions of teacher competence in relation to ASD, such as attitudes (AAST,

Olley et al., 1981), self-efficacy (ASSET,

Ruble et al., 2013), or conceptual knowledge (AKSS,

Derguy et al., 2022). However, these tools typically focus on isolated constructs, limiting their capacity to capture the interaction between cognitive, socio-emotional, and practical factors. The

AET (

2022,

2023) Professional Competency Framework has served as an international reference by systematizing key competency areas, although it is primarily conceived as a training guide rather than a validated psychometric scale. In this context, the

DocenTEA questionnaire represents an advance by integrating five interrelated dimensions into a single validated instrument, enabling a more comprehensive assessment of teacher preparedness and the identification of both strengths and training gaps in diverse educational contexts.