1. Introduction

In Taiwan, a variety of languages are spoken, including Mandarin, Hokkien, Hakka, and several indigenous languages, each reflecting distinct cultural traditions.

Tsao (

2010) explicated the multilingual landscape in his research on language planning in Taiwan, while

S. Chen (

2010) pointed out the three entangled threads of languages, Mandarin, English and local languages, that have been influencing the language policy making in Taiwan. Besides Mandarin as the most widely used language, the Taiwanese government developed two significant language policies in the past decades. First, to preserve and promote linguistic diversity, the government enacted the Development of National Languages Act, which supports the preservation and development of local languages. This policy focuses on the revival of declining local languages and maintaining the cultural identity of various minority groups. Second, due to the increasing emphasis on internationalization, both the government and the public have been placing greater emphasis on the role of English as a global lingua franca to align with the worldwide community and enhance the international competitiveness of the country. As a result, the

Bilingual 2030 policy was announced.

To make Taiwan a pivotal force in the global economy and create higher-quality job opportunities for its citizens, the government launched a top-down initiative—the Bilingual 2030 policy. This reform aims to incubate a more bilingual and globally competitive future generation by enhancing their linguistic skills, cross-cultural insights, cognitive growth, and financial opportunities (

Y. S. Freeman et al., 2018). To achieve this goal, the National Development Council (NDC) and the Ministry of Education (MOE) coordinate all available resources to actively implement the Bilingual 2030 policy in several tasks, including bilingual education in primary, secondary, and higher education, the development of digital learning, the implement of English proficiency test, the enhancement of English proficiency of civil servants, and the establishment of dedicated administrative body to manage the policy’s implementation. At the primary and secondary education levels, the MOE promotes bilingual instruction in specific subject areas, such as physical education (PE), arts, and integrated activities nowadays. Nevertheless, some societal voices oppose the bilingual education policy, citing concerns such as its potential impact on native language policies and the gap between policy and practice in bilingual education (

H. Y. Lin et al., 2025).

Furthermore, several challenges are raised when implementing bilingual instruction in primary schools. The major reason is that pre-service teacher training programs tend to focus on specialized subjects in specific areas. Also, as Taiwan is a Mandarin-speaking society, the training programs are typically delivered in Mandarin. The lack of English language training, bilingual instruction knowledge, and practice in bilingual instruction cause difficulties in implementing bilingual education for teachers in primary schools. Moreover, the implementation of the bilingual education policy has led to curriculum overload for teachers. A significant amount of time and effort is devoted in the bilingual instruction, which might affect their original teaching tasks. Without adequate support, teachers usually feel exhausted and overwhelmed (

Y. P. Huang & Tsou, 2023).

Several approaches are proposed to facilitate the implementation of bilingual instruction from different perspectives (

Y. P. Huang & Tsou, 2023;

T.-B. Lin, 2021c). The first one is focus on the improvement of English capability of teachers who participate in bilingual instruction. Researchers argue that subject teachers should possess at least B2-level language proficiency, holding that bilingual instruction should be aimed at development of students’ content knowledge and language knowledge. Other researchers, however, advocate developing localized bilingual models for subject teachers, insisting that bilingual professional learning community (BPLC) will better support subject teachers for bilingual instruction. Lin, for instance, argues that some subject teachers are not proficient in English, but they can have support in BPLC to better implement bilingual instruction (

T.-B. Lin, 2021a).

Limited studies examine the effective operation of BPLC at the primary school level in Taiwan. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the functionality and benefits of BPLC for subject teachers with limited English proficiency in bilingual instruction. In this study, the BPLC consists of three members: a subject teacher who is responsible for the bilingual PE class, an experienced colleague from the same subject area, and an English teacher with in-depth knowledge of English language and bilingual education. Results show that a well-organized and positive BPLC can effectively help subject teachers with limited English proficiency through real-time support and long-term development guidance in bilingual instruction.

The manuscript is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents a literature review on bilingual education in Taiwan from multiple perspectives.

Section 3 outlines the research method.

Section 4 elaborates on the findings, followed by corresponding discussions in

Section 5. Finally,

Section 6 presents the conclusion and directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

In Taiwan, the Development of National Languages Act and the Bilingual 2030 Policy were enacted by the government to preserve local languages and promote alignment with international standards. The study focuses on the practical implementation of the Bilingual 2030 Policy. This section provides an overview of bilingual education in Taiwan, with a focus on its key challenges. It then discusses localized bilingual instruction models in response to Taiwan’s unique educational context.

2.1. Bilingual Education in Taiwan

According to the 2030 Bilingual Policy announced by Taiwan’s Executive Yuan in 2018, it is expected to strengthen citizens’ English communication skills, particularly among young people, and enhance their global competitiveness (

National Development Council, 2018). However, the policy documents provide limited clarity regarding language use, instructional time, and implementation standards for bilingual education. This ambiguity has led to varied interpretations and inconsistent practices among educational institutions and teachers (

Ferrer & Lin, 2024).

According to the 2030 Bilingual policy and the 12-Year Basic Education Curriculum Guidelines, English should be both an academic subject and a language of communication in schools. However, Taiwan is a Mandarin-speaking society, and the availability of qualified subject teachers capable of delivering bilingual instruction remains a significant concern (

Wang, 2020,

2024). Although the MOE has authorized universities to conduct bilingual enhancement programs for in-service teachers since 2020, the development of adequate bilingual teaching skills and lesson planning abilities cannot be fully achieved within the limited duration of these training programs. It remains challenging to implement bilingual instruction effectively.

During the implementation of bilingual instructions, teachers encounter diverse difficulties and challenges in different aspects. When interpreting the policy, unclear policy directives often lead to implementation struggles in bilingual education (

K. M. Graham & Yeh, 2023;

K. M. Graham et al., 2021). Furthermore, models used abroad (

S. W. Chen & Chou, 2019;

C. Y. D. Chen & Lin, 2021;

H. L. S. Chen & Yeh, 2024) may not be suitable for the educational context in Taiwan. Based on the perspective of two in-service subject teachers who participated in bilingual enhancement programs provided by the MOE,

Lo (

2021) revealed the struggles from both the teacher’s and learners’ aspects. The study revealed that the content instruction in two languages was too challenging for some students to comprehend. Subject teachers invested more time and effort in lesson preparation when collaborating with foreign teachers, as co-teaching is expected in bilingual instruction. They mentioned that they expected support from English teachers, despite their language proficiency being at the B1–B2 level. Similarly,

H. H. Chen (

2023) investigated the professional identity transition of five in-service teachers involved in implementing a science-CLIL project. Moreover, researchers advocate that Taiwan cannot simply transplant bilingual instruction models from other countries (

T.-B. Lin, 2021b,

2021c). Instead, Taiwan’s bilingual instruction model should be developed to reflect its specific educational and social context, whereas various models of bilingual instruction are practiced in schools.

2.2. Models of Bilingual Education and Challenges in Taiwan

To implement bilingual education, most schools in Taiwan participated in bilingual education projects supported by local governments or the MOE. It has been reported that nearly one-third of public schools in Taiwan offer bilingual education (

H. P. Huang, 2021;

Liang, 2022). Ideally, each school adopts a bilingual instruction model that suits its educational context. Among various approaches, three common bilingual models in public schools are commonly observed, including Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL), English as a Medium of Instruction (EMI), and immersion (

H. P. Huang, 2021). Several studies introduced CLIL concepts and shared lesson learned drawn from teachers’ experiences and administration’s perspective in Tainan City (

Tsou & Kao, 2018;

Y. P. Huang & Tsou, 2022;

Kao, 2021). In addition,

Luo (

2021) provides specific insights into CLIL through a questionnaire and interviews from teachers’ perspectives. It also revealed several challenges within the CLIL model, including teachers’ unfamiliarity with the concept, the lack of CLIL-specific textbooks, gaps in subject teachers’ language proficiency, and teacher pushback.

However, the implementation of the immersion and EMI model also faces challenges, including the development of bilingual teaching materials, assessment practices, and issues related to language proficiency. According to

T.-B. Lin and Wang (

2023), bilingual instruction should prioritize the delivery of content knowledge rather than English. Strategies such as increased listening input, visual support, and targeted keywords may help students to learn subject matter more effectively. In other words, language proficiency and curriculum design represent core challenges in bilingual instruction. More support should be given to subject teachers in either CLIL or immersion models, particularly in terms of instructional resources and professional development (

H. H. Chen, 2023;

Luo & Chen, 2022).

Notably, Lin advocated for a localized model for designing and implementing bilingual education in Taiwan, known as the FERTILE model (

T.-B. Lin, 2021c).

Chang and Tsou (

2025, p. 158) illustrated the key idea behind the model:

Lin states that bilingual education is the enactment of “linguistic pluralism” and a form of resistance towards a “monolinguist” one nation-one language perspective (in the case of Taiwan, it would be to go beyond the scope of Mandarin). … he further challenges the idea of “standard English”: if the goal of bilingual education is communication, it is more crucial to embrace diverse varieties of English.

Moreover, the FERTILE model suggests seven principles, ranging from macro-level considerations at the school level to micro-level practices in bilingual classrooms. The principles are as follows:

Flexibility: maintain flexibility when designing and implementing bilingual education;

Environment: environment establishment is also a key to successful bilingual education;

Role modeling: stakeholders, such as subject teachers, English teachers, and administrative roles can be role models to students;

Time: allocate sufficient time for the development of bilingual education in schools;

Instructional strategies: develop appropriate instructional strategies such as applying multimodal resources;

Learning needs analysis and differentiated instruction: provide differentiated instruction based on precise identification of students’ subject knowledge and English proficiency;

Engaging stakeholders: all the stakeholders need to proactively participate in the promotion of bilingual education.

The FERTILE model approaches bilingual education from a more comprehensive and macro perspective (

T.-B. Lin & Wu, 2021;

Tsai, 2024). Furthermore, Lin advocates for building a bilingual community as a response to bilingual education, recognizing that in-service subject teachers may initially lack sufficient language proficiency or confidence during the early stages of implementation (

T.-B. Lin, 2021a,

2021b).

3. Methods

This study aims to investigate the functionality and benefits of BPLC in bilingual instruction. It seeks to address the following two main research questions:

How can a BPLC support bilingual teachers in their teaching and help bridge language gaps?

How can bilingual teachers with limited English proficiency develop bilingual teaching procedures through participation in a BPLC?

The qualitative case study approach is employed to gain an in-depth and holistic understanding from the perspective of BPLC, with a focus on the aspects of English language usage and the significant transition of the subject teacher. The two aspects are comprehensively documented and analyzed in order to explicate the support provided by BPLC.

A bilingual PE class in an elementary school is selected as the case for observation. Data collection lasted for eight months, from October 2024 to June 2025. The types of data include field notes from classroom observations, records of BPLC discussions, semi-structured interviews, and the researcher’s reflections. Two semi-structured interviews, each lasting about one hour, were conducted with the subject teacher with limited English proficiency to gain more insights into the challenges and supports from BPLC. With various data sources, triangulation has been carefully conducted to ensure the validity of the study.

3.1. Context: The Research Field

The field of this study is at an affiliated elementary school located in eastern Taiwan. With a total of 42 classes, it is the largest elementary school in the county. Like other affiliated elementary schools, policy enactment is one of their primary responsibilities. Therefore, since 2020, the school has been required to invest significant effort in implementing the Integrated Bilingual Teaching in Selected Subjects project (the flagship bilingual teaching program funded by the Ministry of Education) and the Taiwan Foreign English Teacher Program (TFETP) in support of the 2030 Bilingual Policy. Under the Integrated Bilingual Teaching in Selected Subjects project, English is used as one of the languages of instruction in art and PE classes at the fourth grade. All fourth-grade students will have two visual art periods and three PE periods each week, both delivered through bilingual instruction. These classes are taught by local subject teachers. Additionally, through TFETP, one foreign English teacher is recruited to create more opportunities for students to learn English at the school. The foreign English teacher is responsible for English language classes only and does not participate in bilingual instruction.

In summary, the affiliated elementary school has qualified and stable teachers, good academic performance, and a positive learning environment, making it suitable for implementing new educational policies and conducting corresponding research studies.

3.2. Research Participants

The members of the BPLC comprise three subject teachers, focusing on English, PE, and the educational field (see

Table 1). Each member has over ten years of experience in their specific domain. Notably, the community is a bottom-up BPLC initiative led by the English teacher (ET), who is also the researcher of this study and has strong interests in both the research and practice of bilingual instruction. The PE teacher (PET) is a novice at bilingual instruction. She is open-minded and willing to open her class for classroom observation. The English teacher also invites a homeroom teacher (HT) to participate in this bottom-up community to further explore the issues in bilingual instruction. All members participate actively in the BPLC. Reflecting on the collaboration, the subject teacher stated “

I am so joyful about all that we’ve done in this academic year”.

In addition to their teaching experiences, it is worth noting their academic background. The homeroom teacher obtained a Doctor of Philosophy degree in 2024 by conducting bilingual action research applying the FERTILE model. She possesses extensive experience in lesson planning and school administration. The English teacher holds a degree in TESOL and participated in the “Integrated Bilingual Teaching in Selected Subjects” project from 2021 to 2022. Regarding the subject teacher, she is an expert in PE but lacks proficiency in English. Her English proficiency is at the CEFR A1 level. She can use basic sentences to introduce herself and use simple words or limited daily expressions to communicate with others. However, she sometimes has difficulty with pronunciation and unfamiliar expressions in the context of bilingual instruction. As she mentioned, “Although my English skills are limited, I’m making an effort to learn for bilingual instruction.”

Specifically, the homeroom teacher served as a research witness in the study. She not only participated in classroom observations but also contributed to discussions in the BPLC meetings. Through interactions with other community members, she gained insights into bilingual teaching strategies and instructional language use. Additionally, she generously shared her perspectives on curriculum design during the BPLC meetings.

3.3. Landscape of the Bilingual Classroom

The Integrated Bilingual Teaching in Selected Subjects project was implemented with fourth-grade students. These students have one English class per week under the K–12 curriculum guidelines in Taiwan, as well as a school-based curriculum focused on cultural learning with English teachers. Most of the students’ English proficiency levels are below the Pre-A1 level.

The bilingual PE class offers an alternative pathway for students to acquire English within the school context. Given the limited English proficiency of both the PE teacher and the students, the CLIL and Immersion models of bilingual instruction were not considered suitable for this context. Instead, English was integrated into routine classroom interactions to create opportunities for language use between teachers and students. Mandarin remains the primary medium for delivering subject-specific content knowledge, thereby ensuring conceptual clarity and promoting student engagement.

3.4. Data Collection and Analysis

The data for this study were collected through long-term classroom observations, BPLC discussions, and semi-structured interviews with the subject teacher responsible for bilingual instruction. The research focuses on teachers, aiming to enhance their practices. Data on classroom observations of the teacher’s bilingual instruction were collected each period, lasting 40 min, and were conducted weekly.

The non-participant observation approach was employed in the classroom observations to collect data from natural learning environments. In addition, data from the BPLC discussions were collected through a participatory approach, focusing on the subject teacher’s thoughts and findings related to bilingual instruction, including teacher-student English use, classroom management, and lesson planning.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted at the end of the semester to revisit the instruction from the subject teacher’s perspective. The interview guide explored the following areas: (1) teachers’ experiences in bilingual instruction, (2) the impact of the BPLC, and (3) the features of bottom-up BPLC. Grounded theory was employed to analyze the data through an iterative and comparative process, using inductive analysis of all sources (

Creswell & Poth, 2023). The data were coded and categorized inductively based on issues that emerged during the BPLC meetings in order to identify the main benefits of the BPLC and the transformation experienced by the teacher. To enhance the trustworthiness of the findings, triangulation of data sources and member checking were implemented throughout the process of data collection and analysis.

4. Findings

Based on classroom observations, BPLC discussions, and semi-structured interviews, the functionalities and benefits of the BPLC are identified. In analysing the data, two knowledge categories emerge: (1) Real-time feedback: Revisit the BPLC perspective and (2) Long-term development guidance: BPLC as an incubator. Each category is unique in terms of the issue it addresses and the source from which it came. Findings and supporting evidence are introduced in the following sections.

4.1. Real-Time Feedback: Revisit BPLC Perspective

Subject teachers with limited English proficiency often face difficulties in conducting bilingual instruction. Without the help of BPLC, subject teachers encountered difficulties in wording, pronunciation, and timing when using English. The situation could have a negative impact on the originally planned curriculum. The subject teacher provides lesson plans and materials that she intends to teach during bilingual lessons. Thus, BPLC members can gain more knowledge about the class in advance and provide suggestions (e.g., precise or proper wording and sentences) to the subject teacher. Additionally, the English teacher conducts classroom observations on a weekly basis. After the class, all BPLC members will have a discussion covering topics such as language usage, classroom management, and lesson planning. This kind of real-time feedback from BPLC provides instant support and facilitates the implementation and reflection of bilingual instruction at the classroom level.

4.1.1. BPLC as a Supporting System

Bilingual instruction presents a significant challenge for subject teachers in their professional careers. Nevertheless, it also serves as an alternative approach to curriculum reinvention, promoting teachers’ professional development. The BPLC can accompany subject teachers on this challenging journey. For instance, the language teacher shared a teaching method, Total Physical Response (TPR), in the field of English pedagogy (

D. L. Freeman & Anderson, 2011). In this method, the meaning of the target language can be conveyed through physical actions. This effectively helps students and subject teachers connect actions with words during learning and teaching.

Through classroom observations and discussions facilitated by BPLC, subject teachers received support via brainstorming, feedback, and suggestions from various perspectives, including English language usage, classroom management, and lesson planning in the bilingual instructional setting.

ET: Put tissue paper in the box (with gestures)

PET: How to spell the word … “tissue”

(The subject teacher tried to write down the sentences)

ET: Or you can try this sentence …

PET: Hold on! Hold on!

HT: She is overloaded now.

PET: You can read my mind!

ET: I see! “Put “it” in the box.” (Total Physical Response)

(BPLC note, December 2024)

PET: I am a subject teacher as well as a language learner. Throughout this semester’s discussions, I acquired practical approaches and gained my bilingual teaching practices.

(Interview, January 2025)

PET: Regularly meet after classroom observation, and both of you provide feedback on English usage, teaching procedure, or learners’ performance. Sometimes, May (HT) shared her ideas, and we refined the content and made it more comprehensive. We tried to create more chances to use English in teaching. These discussions were focused on the teacher’s and students’ interactions during the session, making them both timely and effective.

(Interview, January 2025)

PET: I really appreciate our weekly discussions. I’ve learned a lot from each one, whether it’s about curriculum ideas or bilingual teaching.

ET: I’ve noticed you’re more confident in using English during your teaching than you were last semester. It’s great to see that you can sometimes aware and correct mispronunciations immediately.

(BPLC note, March 2025)

PET: I truly appreciate this BPLC in this academic year. You provide suggestions on teaching materials and strategies, and help shorten my sentences when I struggle to speak.

(Interview, June 2025)

The subject teacher with limited English proficiency struggles to maintain the planned teaching progress during bilingual instruction. In such situations, students may lose interest or feel uncomfortable, which will negatively impact the learning process. The BPLC members offer practical strategies for managing the classroom in convenient English to be applied through discussions. This reduces the burden on the subject teacher and makes the bilingual class run more smoothly.

PET: The kids are too noisy. … Using English slows down my teaching pace. When I use English, I can’t catch their attention immediately.

ET: I read some articles that other teachers have the same experience at the beginning of bilingual teaching.

PET: Really! I struggle to teach as smoothly as before when using English. My English is poor.

ET: Simple words, gestures, and a raised tone are tips to catch kids’ attention. We can try it in the future.

(BPLC note, October 2024)

PET: I applied the classroom management tips you shared last week to my other classes. It works!!

(BPLC note, April 2025)

PET: I love it when we discuss how to refine bilingual teaching in post-classroom observation meeting.

ET: You’re using English more naturally during your teaching than you were last semester. It’s great to see that you are aware and self-monitor in bilingual instruction.

PET: Hope we have time to focus on the bilingual teaching issue in the new semester.

ET: I appreciate your trust and I also learn some PE knowledge from each discussion.

(BPLC note, May 2025)

PET: The discussion group is a unique bilingual professional learning community; we were involved in bilingual teaching.

(Interview, June 2025)

4.1.2. From Errors to Mistakes: Revisit the Language Use in Class

The subject teacher with limited English proficiency makes errors during bilingual instruction. It is difficult for the subject teacher to diagnose the mistakes during teaching. Thus, through classroom observations and discussions by BPLC members, mistakes can be recorded, identified, and addressed. The subject teacher can receive real-time feedback and suggestions to make corrections or refinements after each bilingual lesson.

PET: Good afternoon, boys and girls… *rise/raɪz/your hand…

(Classroom observation filed note, October 2024)

ET: I recorded one pronunciation error with the word ‘raise’ in the phrase raise your hand. PET: raise your hand (repeat 2 times)

(BPLC note, October 2024)

PET: Boys and Girls, let’s *read together.

(Classroom observation filed note, November 2024)

ET: I recorded one pronunciation problem with the word ‘read’ in the class. In the context, the vowel a long vowel, not a short vowel/rɛd/.

ET: read (basic form)-read (past simple)

PET: I see! (Take notes and repeat several times)

(BPLC note, November 2024)

With the support of BPLC, the subject teacher’s language awareness is gradually being established. In the later phase of the observation period, subject teacher can recognize the mistakes and make the correction immediately. The improvement in bilingual instruction of the subject teacher can be attributed to the involvement of the BPLC. The following examples illustrate the subject teacher’s self-correction of pronunciation and word choice.

ET: (A slip of the tongue), “*rise your hand” appeared in teaching, you corrected the pronunciation “raise” immediately.

PET: I said the phrase, and immediately corrected it when I was aware of pronunciation mistakes... I still remember tips on how to pronounce ‘raise’ and ‘rise’ correctly.

ET: GREAT!

(BPLC note, April 2025)

ET: The box is in your hand, you said ‘Guess, what’s *that?’ The correct sentence is ‘What’s in the box?’ or ‘what’s this inside the box?’ this means ‘close to you’.

PET: Can you say the sentence again? (PET take notes)

ET: … The word ‘this’ means ‘close to you’, and ‘that’ means ‘far away’. (ET says two words slowly and uses gestures to explain the concept of position)

(BPLC note, March 2025)

PET: What’s tha. (A slip of the tongue) What’s this?

(Classroom observation Filed note, April 2025)

ET: You quickly correct yourself when you make a mistake while speaking.

PET: Absolutely! As soon as I said the sentence, I knew ‘that’ wasn’t the correct word choice.

(BPLC note, April 2025)

4.2. Long-Term Development Guidance: BPLC as an Incubator

In addition to real-time feedback, the BPLC serves as a long term observer and supporter for the subject teacher. For the subject teacher with limited English proficiency, implementing bilingual instruction is also a learning task with its own challenges. Through sustained classroom observations and regularly scheduled discussions, the actual performance of subject teachers can be documented, identified, and analyzed. Thus, BPLC members can gain an overview of the development trajectory of the subject teacher and provide timely and appropriate suggestions. Several questions will be carefully considered during the process, such as (1) Based on the current status of the subject teacher, should the amount of English used in the class be increased or decreased; (2) Based on the current status of the subject teacher, should the variety of wording or sentence pattern be enriched; and (3) Should the status quo be maintained due to the feeling or burden on the subject teacher. Through the continuous observation and evaluation, the BPLC can design a personalized developmental trajectory to support the subject teacher in bilingual instruction.

PET: I’ll never forget my first bilingual PE class—I only used two or three English words. I prepared a lot, but I forgot everything in teaching.

(Interview, January 2025)

ET: I’m glad to take part in your bilingual instruction every week. Your initial experience with bilingual teaching is a wonderful opportunity for in-depth observation.

PET: I appreciate you and May being here with me to refine my teaching. Regular meetings and feedback have greatly supported my bilingual instruction. I’m so grateful for your help.

(Interview, January 2025)

PET: I’ve gained more confidence in bilingual teaching, and I’ve learned a lot from this BPLC. I’m able to notice mistakes during class and correct them immediately.

(June, January 2025)

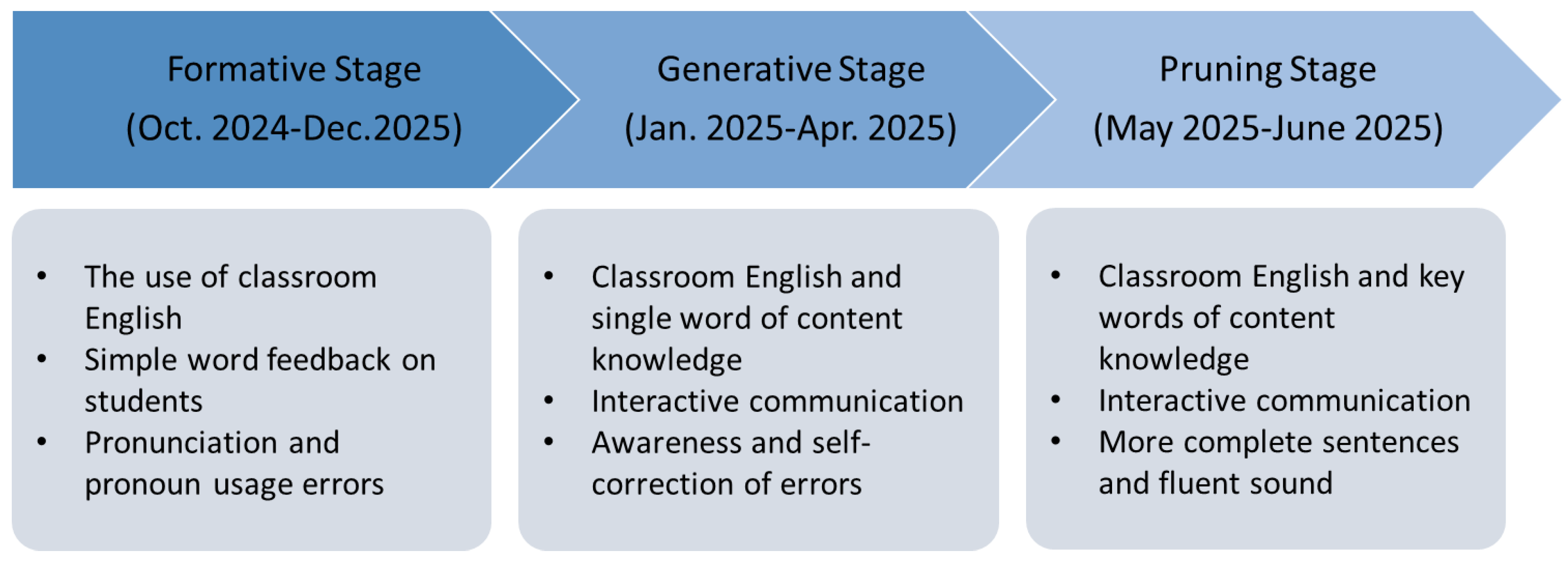

Three distinct stages, including the formative stage, the generative stage, and the pruning stage, were identified through continuous classroom observations and discussions. The trajectory of teacher development over time is illustrated in

Figure 1. Furthermore, the progression of language use and discussion topics related to developing bilingual teaching in the BPLC, as described by its members, is presented in

Table 2. The data reveals the language use features in different stages and the corresponding strategies provided by the BPLC. Based on the suggestions, the subject teacher can shift to advanced stages of bilingual instruction effectively. Regarding the formative stage as the beginning of bilingual instruction, English greetings and end-of-class expressions serve as entry points into bilingual instruction. Using a fixed pattern can be a practical strategy for subject teachers to start bilingual instruction with less stress. Take the following extract, for example:

At the formative stage, the talking points of BPLC primarily focus on providing positive feedback in bilingual instruction, as well as some phonological knowledge in speaking, to enhance the subject teacher’s language knowledge and confidence in bilingual instruction. Providing a basic daily English pattern, such as hurry up, let me see it, watch out in BPLC, is a way to expand the language use of the subject teacher in instruction. Notably, a trusting and supportive atmosphere within the BPLC also helps to reduce the affective load of the subject teacher during classroom observations and discussions.

At the generative stage, the subject teacher demonstrates greater variety and flexibility in language use (e.g., “Look at him”/“Put away your schoolbag”) and asks some yes/no questions to create an authentic, interactive language use environment in teaching. The subject teacher can recognize and self-correct some mistakes (e.g., mispronunciation) immediately while teaching. The English teacher can intentionally suggest and demonstrate key vocabulary related to content knowledge to help bridge the gap between subject and language knowledge. At this stage, BPLC members can provide additional ideas, such as morphological knowledge, the Total Physical Response (TPR) method, and language drill templates, to help the subject teacher develop advanced bilingual instruction skills.

At the pruning stage, the focus is on maintaining the growth of the subject teacher in bilingual instruction through continuous BPLC discussions, as well as refining bilingual teaching. It is time to broaden the focus by establishing a personalized language use pattern or developing a language corpus in bilingual instruction, and by integrating multimodal strategies into bilingual teaching to achieve the previously stated goals.

To sum up, at the micro level of bilingual instruction, using simple greetings with learners at the start of class represents the initial move in bilingual discourse. Straightforward English is then employed to conclude the class, followed by an expansion of language use at both the beginning and end of the lesson. Finally, subject content knowledge is conveyed in simplified English. Through long-term and continuous class observations and discussions, the progress and performance of the subject teacher in bilingual instruction can be systematically and effectively recorded, evaluated, and analyzed. Moreover, based on the collected evidence, the BPLC can provide timely and personalized guidance for the subject teacher, which facilitates the effective implementation of bilingual instruction.

5. Discussion

The challenges that subject teachers face in bilingual instruction are beyond the imagination of those teachers with sufficient English proficiency. The functionalities and benefits provided by BPLC members in supporting the design and implementation of bilingual instruction in an elementary school in Taiwan were investigated in this study. Some recommendations based on the findings are presented below.

The findings highlight the importance of a bottom-up BPLC as a key support system for effective bilingual instruction, particularly for subject teachers with limited English proficiency. Previous studies have revealed that subject teachers face several challenges, including language proficiency gaps, teaching progress, learners’ responses, and teaching anxiety in bilingual teaching (

K. M. Graham & Yeh, 2023;

Lo, 2021). Additionally, the emotional stress and workload associated with both bilingual instruction and original teaching tasks can become overwhelming for subject teachers. Without the support of BPLC, it is challenging for subject teachers to address the above challenges independently. Based on these findings, it is highly recommended that establishing a BPLC support subject teachers in bilingual instruction. This recommendation aligns with the concept of a bilingual professional learning community, as proposed by

T.-B. Lin and Wu (

2021) for junior high school bilingual subject teachers. Our findings prove that it is also functioning well in the elementary setting.

The organisation and composition of the BPLC requires careful consideration to maximise its effectiveness. A local English teacher as a core member in the BPLC is essential because the English teacher can accurately assess the English language proficiency of subject teacher and students during classroom observations, thereby providing timely and appropriate support in the areas of language proficiency and lesson planning. As

T.-B. Lin (

2021a) states, an English teacher can function as an experience sharer, a professional developer, and a supportive partner within a BPLC. Moreover, according to the findings of this study, English teachers provide linguistic insights while subject teachers offer content knowledge, resulting in a synergistic and a win-win collaboration.

Additionally, establishing a sense of trust within the BPLC is crucial for its successful operation (

Tsai, 2024;

Chiang, 2024). Trust is the foundation that enables teachers to support one another and share ideas through conversation (

P. Graham & Ferriter, 2009;

Prestridge, 2009). Teachers could adopt a non-critical and open approach in regular discussion meetings to foster and strengthen trust and build relationships. The BPLC requires a positive and relaxed atmosphere to deliberate on events with the subject teachers in a real-time discussion meeting. Most experienced subject teachers are hesitant about incorporating some English in their teaching; they need more emotional support to nurture their confidence in bilingual instruction. This is another key aspect of a successful BPLC. In addition to supporting language proficiency and lesson planning, regular classroom observations and discussions help prevent burnout and maintain the teaching motivation of subject teachers.

Revisiting the BPLC from a spatial perspective, real-time discussion is a way to recall verbal or non-verbal interaction in the class. Bilingual instruction is a dynamic process which should be monitored and adjusted efficiently. During the discussions, the BPLC members constantly review and modify language use, such as pronunciation, word choice, and sentence patterns, without focusing on accent. Based on the atmosphere of the discussion, the BPLC can use proper language to explain language knowledge to subject teachers. Both language knowledge and lesson planning are refined in the discussions.

From a long-term perspective, regular classroom observation documents reveal the language habits and significant progress of subject teachers in bilingual teaching. BPLC can provide appropriate suggestions for subject teachers based on the evidence. Specifically, the recording and the analysis of field notes data reveal language saturation, which can be evaluated from the perspectives of frequency, interaction (turn-taking), and types of language patterns. In short, the evidence not only includes achievements for subject teachers but also authentic data for BPLC members to study how to provide follow-up guidance.

To sum up, these findings establish stages of English use, providing a basis for investigating the strategies of BPLC in non-dominant English contexts, such as Taiwan. From a practical perspective, the local government can organize and implement BPLCs within the region to support schools that lack sufficient personnel to provide bilingual instruction. For novice bilingual teachers, the framework of language stages outlines the types and characteristics of language at different developmental phases, offering a structured guideline for self-improvement and self-monitoring in bilingual teaching practice. They can also be applied to generate ideas in bilingual instruction, as well as in bilingual professional learning communities, across various national settings.

6. Conclusions

Based on the findings, it can be observed that BPLC provides significant support to subject teachers with limited English proficiency, a common challenge in the educational environment in Taiwan. The establishment and operation of BPLC is a practical and effective approach toward the successful design and implementation of bilingual instruction.

Based on the findings, this study provides the organization and composition of BPLC, and emphasizes the importance of professional English teachers. Moreover, the findings suggest that high agency members in the BPLC can boost positive interaction relationships; in other words, the BPLC is not only a bilingual instruction community but also a cross-disciplinary one in the school. Mutual trust and a supportive atmosphere within the BPLC are essential to facilitate collaboration and development among all members using bilingual instructions.

Regarding the operation of the BPLC, the study highlights the benefits of frequent and continuous classroom observations and discussions. Through the observations and discussions, real-time feedback and support can be provided, especially for subject teachers with limited English proficiency, who often struggle with the wording and pronunciation in bilingual instruction. Moreover, the long-term accumulation of data from classroom observations and discussions allows the BPLC to develop a comprehensive understanding of the subject teacher in bilingual instruction. This understanding helps to construct the language development stages of the subject teacher and suggests the talking points of the BPLC for professional development. Based on the trajectory, the BPLC can offer personalized and appropriate guidance in English language usage, teaching tips, or lesson planning, thereby improving the effectiveness of bilingual instruction and the growth of the subject teacher.

In conclusion, this study investigates the key characteristics of a bottom-up BPLC in supporting subject teachers with limited language proficiency and in bridging the language gap during the implementation of bilingual instruction. The effects of bilingual project participation on learners’ performance warrant further investigation in future research. Although the study is limited by a small number of participants, which may affect the generalizability of the findings, the results offer valuable insights for enhancing support for bilingual teachers in English-as-a-foreign-language educational contexts. Bilingual instruction is a challenging journey for teachers in Taiwan and other non-English-speaking regions. The findings of this study can serve as a stepping stone for future research and practical applications in various educational environments worldwide. As a case study, the findings reveal certain aspects of the operation of a BPLC. More cases can be explored through applying both qualitative and quantitative approaches.