Tandem Teaching for Quality Physical Education: Primary Teachers’ Preparedness and Professional Growth in Slovakia and North Macedonia

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Challenges in the Delivery of Physical Education at Primary Level

1.2. Tandem Teaching as a Professional Development Strategy

1.3. Variations in Tandem Teaching Models in Physical Education

1.4. Rationale and Aim of the Study

- Investigate generalist teachers’ self-perceived level of preparedness for specific pedagogical and organizational aspects of PE lessons, and how they attribute this preparedness to their initial university education, following their experience in a tandem teaching model.

- Assess and prioritize generalist teachers’ self-identified needs for future professional development (e.g., workshops, seminars) that will enhance the quality of PE instruction within the tandem teaching model.

- Compare and contrast the findings between the Slovakian (generalist teachers with external sports coaches) and North Macedonian (generalist teachers with internal PE teachers) models to draw conclusions about the impact of each on teacher preparedness and professional development.

2. Materials and Methods

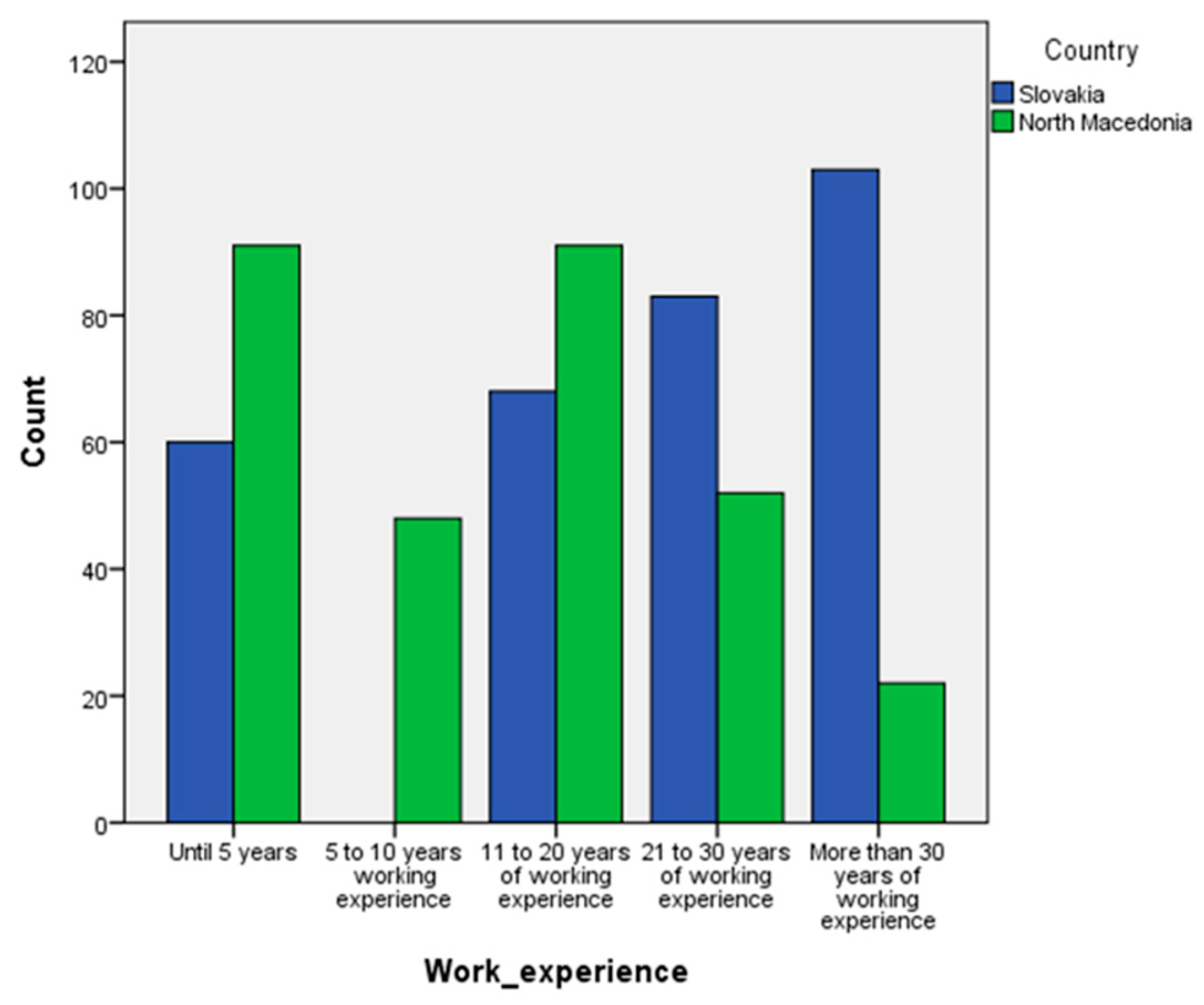

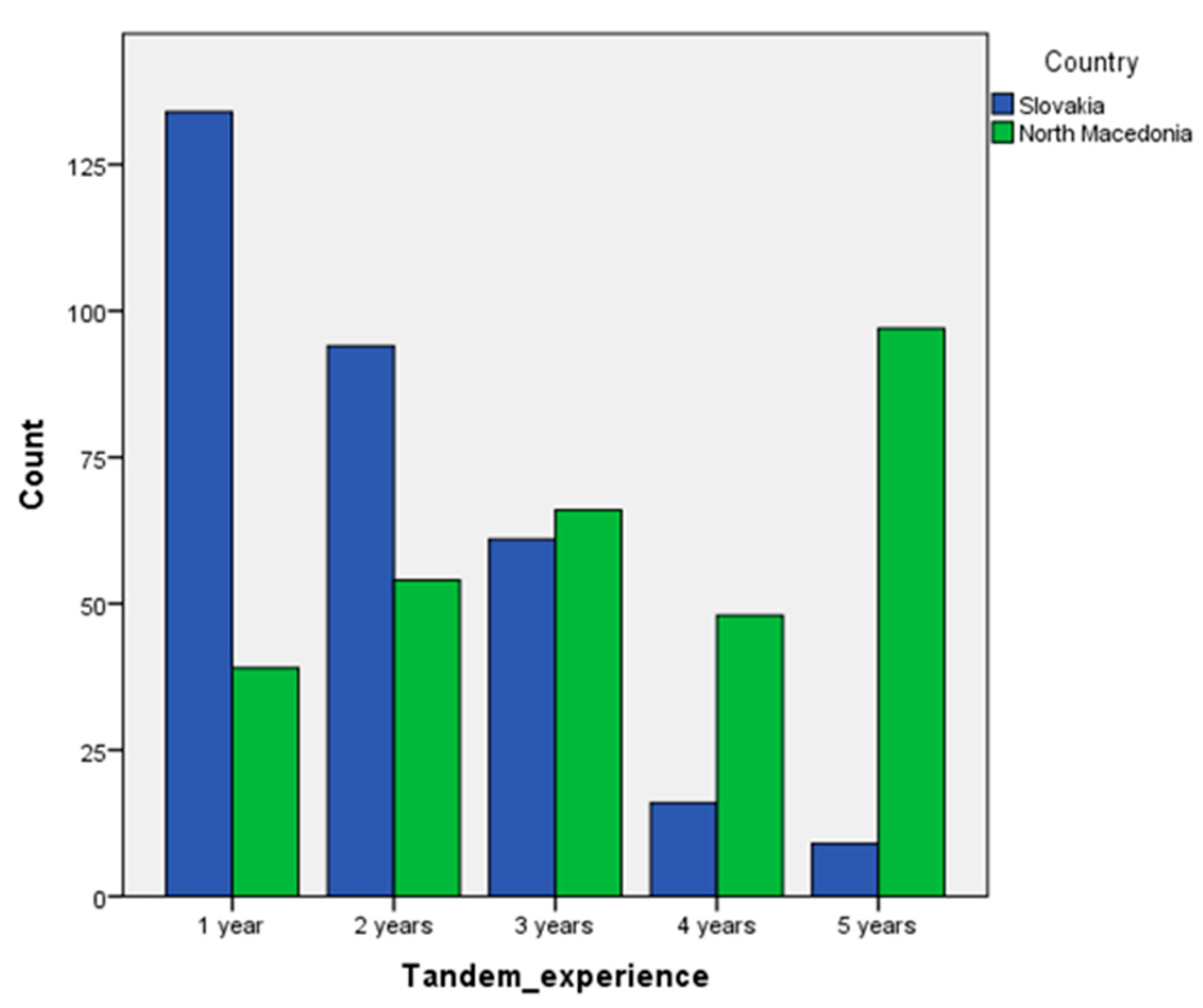

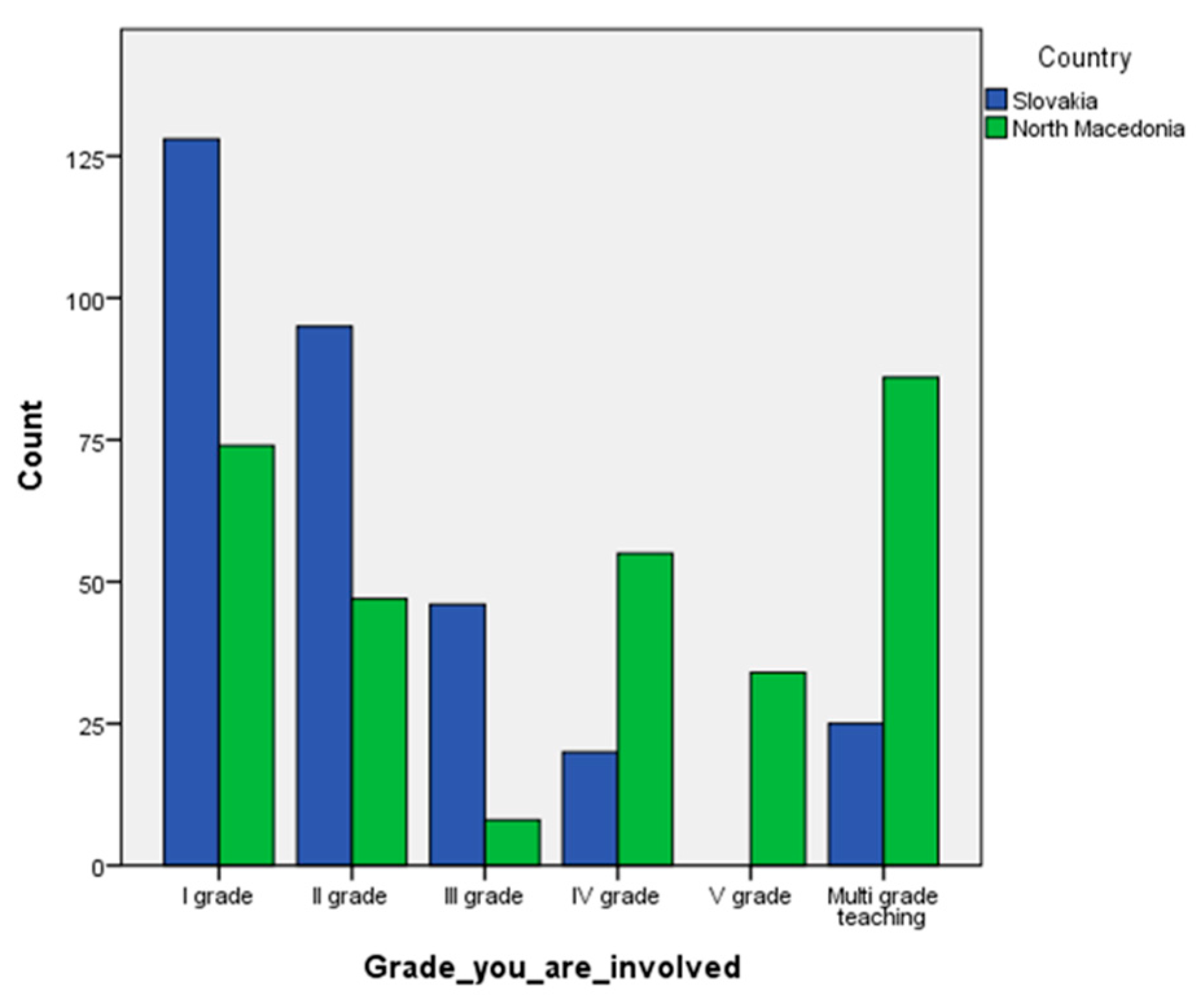

2.1. Study Participants

Ethical Approval

2.2. Data Collection

Validity and Reliability

- Expert Review for Content Validity: The questionnaire was developed and reviewed by a team with expertise in physical education and education, which functioned as an internal expert committee. This ensured the instrument was precisely tailored to capture a comprehensive and relevant range of topics (content validity) related to tandem teaching. It used clear, specific language to minimize ambiguity. For example, the questions about teacher preparedness (Question 3) included detailed options on a Likert-type scale, ranging from “I was completely prepared” to “I was not prepared well.”

- Linguistic Equivalence for Reliability: A formal back-translation procedure (Macedonian → English → Slovak) was performed. This was a critical step in ensuring semantic and conceptual equivalence across the different language versions, thereby supporting the reliability and consistency of the instrument across both countries.

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

4.2. Cross-Country Differences

4.3. Casual Factors: Tandem Teaching Structure and Experience

5. Conclusions

- Tandem Teaching as Job-Embedded CPD: Generalist teachers in both countries reported overall moderately high perceived competence across most PE domains. This finding challenges the widespread generalization of low preparedness stemming from ITE deficits. This strong self-perception suggests that tandem teaching acts as a potent, job-embedded professional development strategy that compensates for initial weaknesses and elevates self-reported competence over time.

- The Critical Role of Model Structure and Experience: Despite comparable ITE deficits, North Macedonian teachers, who participate in a sustained, long-term partnership with an internal PE teacher for all weekly lessons, reported being significantly better prepared across most pedagogical and organizational domains than their Slovakian counterparts. This disparity highlights that the structure and longevity of the tandem partnership are critical determinants of professional growth, with consistent collaboration yielding superior results compared to short-term, rotational models.

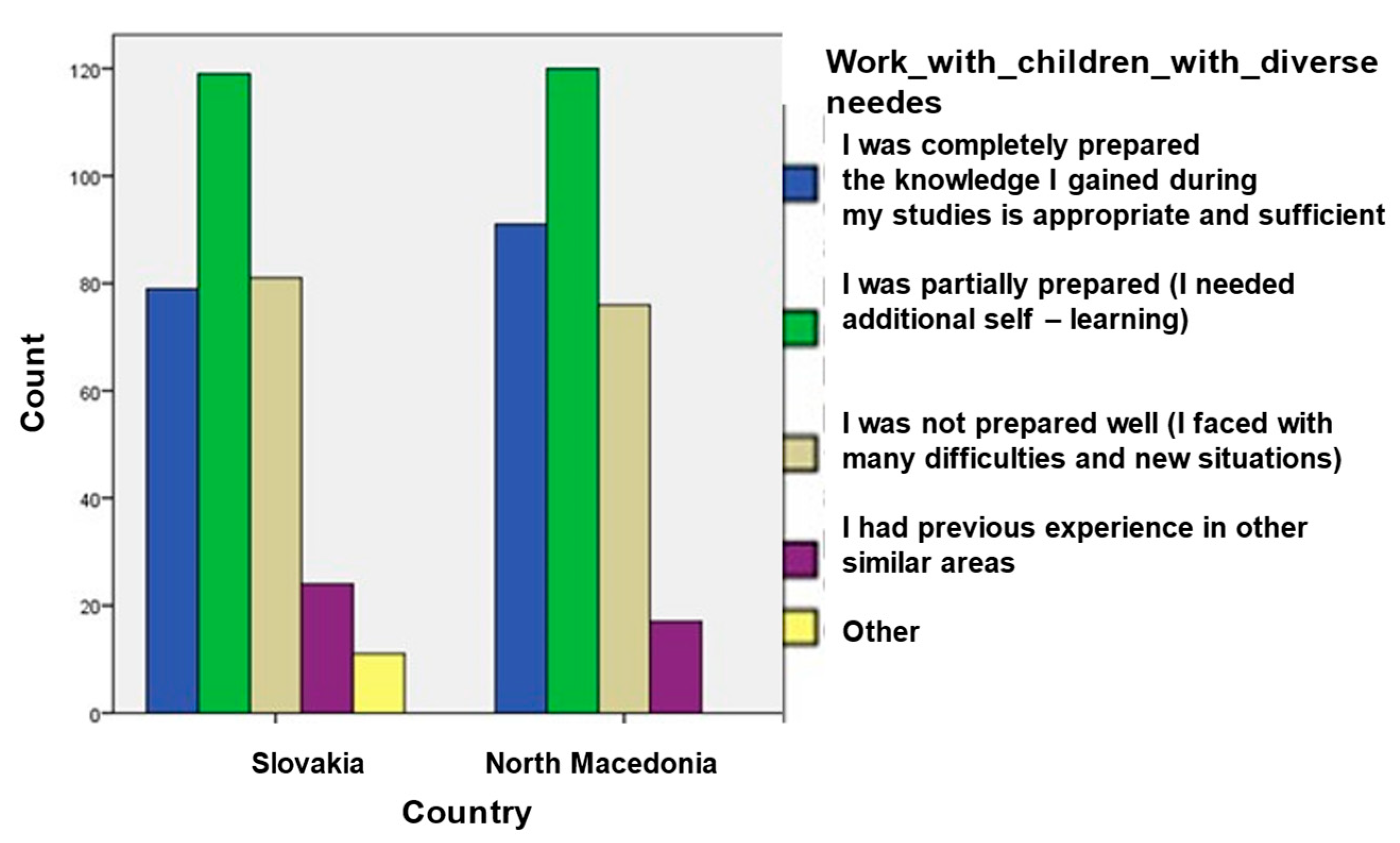

- Shared Systemic Deficit in Inclusive Practice: The only area of consistently low preparedness shared by both cohorts was working with children with diverse learning needs. This consensus identifies a shared systemic weakness in primary teacher education across both national contexts, necessitating targeted ITE enhancement and CPD intervention.

5.1. Practical Implications and Recommendations

5.2. Study Limitations and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CPD | Continuing Professional Development |

| FMS | Fundamental Movement Skills |

| ITE | Initial Teacher Education |

| MVPA | Moderate-to-Vigorous Physical Activity |

| PE | Physical Education |

| PL | Physical Literacy |

| QPE | Quality Physical Education |

Appendix A

References

- Alfrey, L., & O’Connor, J. (2022). Transforming physical education: An analysis of context and resources that support curriculum transformation and enactment. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 29(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliberti, S., Kaçurri, A., Kasa, A., & Giardullo, G. (2025). Stakeholders’ opinions on teaching movement education in primary schools: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 25(2), 423–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio-Herguedas, J. L., Rodríguez-Medina, J., González-Hernández, J. C., & Fraile-Aranda, A. (2020). Teaching skills assessment in initial teacher training in physical education. Sustainability, 12(22), 9668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armour, K., Quennerstedt, M., Chambers, F., & Makopoulou, K. (2017). What is ‘effective’ CPD for contemporary physical education teachers? A Deweyan framework. Sport, Education and Society, 22(7), 799–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeten, M., & Simons, M. (2014). Student teachers’ team teaching: Models, effects, and conditions for implementation. Teaching and Teacher Education, 41, 92–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balga, T., Luptáková, G., Cihová, I., & Dovičák, M. (2024). Evaluating the impact of tandem teaching with coaches and generalist teachers on primary school students’ perceptions in physical education. Collegium Antropologicum, 48(3), 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barák, A., Gurský, T., Macháček, J., & Sližik, M. (2021). Program Tréneri v škole: Metodická príručka. Belianum, vydavateľstvo Univerzity Mateja Bela v Banskej Bystrici. [Google Scholar]

- Bashan, B., & Holsblat, R. (2012). Co-teaching through modeling processes: Professional development of students and instructors in a teacher training program. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 20(2), 207–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basso, D., & McCoy, N. (2009). The co-teaching manual (4th ed.). Twins Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Beamish, W., Bryer, F., & Davies, M. (2006). Teacher reflections on co-teaching a unit of work. International Journal of Whole Schooling, 2(2), 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Carney, P., & Howells, K. (2008). Defining the specialist teacher of primary physical education. Primary Physical Education Matters, 3(3), iii–iv. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, L., & Friend, M. (1995). Co-teaching: Guidelines for creating effective practices. Focus on Exceptional Children, 28(3), 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- D’Elia, F. (2019a). The core curriculum of university training to teach physical education in Italy. Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 19(Suppl. S5), 1755–1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Elia, F. (2019b). The training of physical education teachers in primary school. Journal of Human Sport and Exercise, 14, S100–S104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Isanto, T., & D’Elia, F. (2021a). Body, movement, and outdoor education in pre-school during the COVID-19 pandemic: Perceptions of teachers. Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 21, 709–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Isanto, T., & D’Elia, F. (2021b). Primary school physical education outdoors during the COVID-19 pandemic: The perceptions of teachers. Journal of Human Sport and Exercise, 16(Proc3), S1521–S1535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dockerty, F., & Pritchard, R. (2023). Reconsidering models-based practice in primary physical education. Education 3-13: International Journal of Primary, Elementary and Early Years Education, 52(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncombe, R., Cale, L., & Harris, J. (2018). Strengthening ‘the foundations’ of the primary school curriculum. Education 3-13: International Journal of Primary, Elementary and Early Years Education, 46(1), 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dyson, B., Gordon, B., Cowan, J., & McKenzie, A. (2016). External providers and their impact on primary physical education in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Asia-Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education, 7(1), 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, G., Ceruso, R., Aliberti, S., D’Isanto, T., & D’Elia, F. (2024b). A comparative study of university training of sports and physical activity kinesiologists. BMC Sports Science, Medicine and Rehabilitation, 16, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, G., Di Domenico, F., Ceruso, R., Aliberti, S., & Raiola, G. (2024a). Perceptions/opinions about the formation of the bachelor program in exercise and sports science by students aimed at the new professional profile of the basic kinesiologist. Sport Science and Health, 20, 659–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francesco, C., Coco, D., Frattini, G., Vago, P., & Andrea, C. (2019). Effective teaching competences in physical education. Journal of Physical Education and Sport, 19, 1806–1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freak, A., & Miller, J. (2015). Magnifying pre-service generalist teachers’ perceptions of preparedness to teach primary school physical education. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 22(1), 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurger, H., & Uzuner, Y. (2011). Examining the implementation of two co-teaching models: Team teaching and station teaching. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 15, 589–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L., & Green, K. (2015). Who teaches primary PE? Change and transformation through the eyes of subject leaders. Sport, Education and Society, 22(6), 759–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkpatrick, L., Searle, M., Smyth, R. E., & Specht, J. (2020). A coaching partnership: Resource teachers and classroom teachers teaching collaboratively in regular classrooms. British Journal of Special Education, 47(1), 24–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klincarov, I., Popeska, B., Mitevski, O., Nikovski, G., Mitevska-Petrusheva, K., & Majeric, M. (2018). Tandem teaching in physical and health education classes from teacher’s perspective. In L. A. Velickovska (Ed.), 3rd International Scientific Conference Research in Physical Education, Sport, and Health (pp. 255–262). Ss. Cyril and Methodius University in Skopje, Faculty of Physical Education, Sport, and Health. [Google Scholar]

- Kyndt, E., Gijbels, D., Grosemans, I., & Donche, V. (2016). Teachers’ everyday professional development: Mapping informal learning activities, antecedents, and learning outcomes. Review of Educational Research, 86(4), 1111–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C., & Lorusso, J. (2016). No PE degree? Foundational knowledge to support generalist teachers of physical education. Teaching and Learning, 11(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luptáková, G., Balga, T., Antal, B., Cihová, I., Argajová, J., Dovičák, M., Sližik, M., Gurský, T., & Macháček, J. (2025). Collaborative instruction with external providers in primary physical education: A three-year comparative analysis of generalist teacher perspective. Kinesiologia Slovenica, 31(1), 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makopoulou, K. (2018). An investigation into the complex process of facilitating effective professional learning: CPD tutors’ practices under the microscope. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 23(3), 250–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangione, J., Parker, M., O’Sullivan, M., & Quayle, M. (2020). Mapping the landscape of physical education external provision in Irish primary schools. Irish Educational Studies, 39(4), 475–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mariën, D., Vanderlinde, R., & Struyf, E. (2023). Teaching in a shared classroom: Unveiling the effective teaching behavior of beginning team teaching teams using a qualitative approach. Education Sciences, 13(11), 1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEvilly, N. (2021). What is PE and who should teach it? Undergraduate PE students’ views and experiences of the outsourcing of PE in the UK. Sport, Education and Society, 28(1), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchie, E., Tuytens, M., Devos, G., & Vanderlinde, R. (2018). Evaluating teachers’ professional development initiatives: Towards an extended evaluative framework. Research Papers in Education, 33(2), 143–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, K., Bryant, A. S., Edwards, L. C., & Mitchell-Williams, E. (2018). Transferring primary generalists’ positive classroom pedagogy to the physical education setting: A collaborative PE-CPD process. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 24(1), 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, P., & Bourke, S. (2005). An investigation of pre-service and primary school teachers’ perspectives of PE teaching confidence and PE teacher education. ACHPER Healthy Lifestyles Journal, 52, 7–13. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, P., & Bourke, S. (2008). Non-specialist teachers’ confidence to teach PE: The nature and influence of personal school experiences in PE. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 13, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neutzling, M., Pratt, E., & Parker, M. (2019). Perceptions of learning to teach in a constructivist environment. Physical Educator, 76(3), 756–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nioda, A. J. B., & Tagare, R. L., Jr. (2024). The experiences of non-physical education generalist teachers in implementing PE in the primary grades: Implications for capability development initiatives. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 16(3), 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ní Chróinín, D., & O’Brien, N. (2019). Primary school teachers’ experiences of external providers in Ireland: Learning lessons from physical education. Irish Educational Studies, 38(3), 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordlund, M. (2003). Differentiated instruction: Meeting the educational needs of all students in your classroom. ScarecrowEducation. [Google Scholar]

- Ofsted. (2022, March 18). Research review series: PE. GOV.UK. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/research-review-series-pe (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Penney, D., Pope, C., Hunter, L., Phillips, S., & Dewar, P. (2013). Physical education and sport in primary schools: Final report. University of Waikato. Available online: https://www.waikato.ac.nz/wmier/projects/physical-education-in-primary-schools (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Petračić, T. (2023). The relationship between factors and the quality of physical education teaching in primary school [Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Faculty of Kinesiology, University of Zagreb]. [Google Scholar]

- Petrie, K. (2011). An enduring issue: Who should teach physical education in New Zealand primary schools? Journal of Physical Education in New Zealand, 44, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrie, K., Penney, D., & Fellows, S. (2014). Health and physical education in Aotearoa New Zealand: An open market and open doors? Asia-Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education, 5, 19–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popeska, B. (2022). Tandem teaching in physical education: Current experiences and possibilities for improvement. Goce Delcev University—Stip, North Macedonia. Available online: https://eprints.ugd.edu.mk/31137/ (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Powell, D. (2015). Assembling the privatisation of physical education and the ‘inexpert’ teacher. Sport, Education and Society, 20(1), 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ptack, K., Tittlbach, S., Brandl-Bredenbeck, H. P., & Kölbl, C. (2019). Eine interventionsstudie zum thema gesundheit im sportunterricht: Evaluation eines kooperativen planungsprozesses in der health-edu-studie. Feldhaus, Edition Czwalina. [Google Scholar]

- Qualls, L. W., Arastoopour Irgens, G., & Hirsch, S. E. (2025). Co-teaching as a dynamic system to support students with disabilities: A case study. Education Sciences, 15(6), 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, V. (2023). ‘We want to, but we can’t’: Pre-service teachers’ experiences of learning to teach primary physical education. Oxford Review of Education, 49(2), 209–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, V., & Fleet, M. (2021). Constructing knowledge in primary physical education: A critical perspective from pre-service teachers. Curriculum Studies in Health and Physical Education, 12(1), 20–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, V., & Griggs, G. (2020). Physical education from the sidelines: Pre-service teachers opportunities to teach in English primary schools. Education 3-13: International Journal of Primary, Elementary and Early Years Education, 49(4), 495–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehgal, P., Nambudiri, R., & Mishra, S. K. (2017). Teacher effectiveness through self-efficacy, collaboration and principal leadership. International Journal of Educational Management, 31, 505–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simons, M., Baeten, M., & Vanhees, C. (2020). Team teaching during field experiences in teacher education: Investigating student teachers’ experiences with parallel and sequential teaching. Journal of Teacher Education, 71, 24–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. (2015). Primary school physical education and sports coaches: Evidence from a study of school sport partnerships in North-West England. Sport, Education and Society, 20(7), 872–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R., Ralston, N. C., Naegele, Z., & Waggoner, J. (2020). Team teaching and learning: A model of effective professional development for teachers. Professional Educator, 43(2), 80–90. [Google Scholar]

- Sperka, L. (2020). (Re)defining outsourcing in education. Discourse Studies in Culture Politics Education, 41, 268–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperka, L., & Enright, E. (2018). The outsourcing of health and physical education: A scoping review. European Physical Education Review, 24(3), 349–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sperka, L., Enright, E., & McCuaig, L. (2018). Brokering and bridging knowledge in health and physical education: A critical discourse analysis of one external provider’s curriculum. Physical Education and Sport Pedagogy, 23(3), 328–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spittle, S., Spittle, M., Encel, K., & Itoh, S. (2022a). Confidence and motivation to teach primary physical education: A survey of specialist primary physical education pre-service teachers in Australia. Frontiers in Education, 7, 1061099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spittle, S., Spittle, M., & Itoh, S. (2022b). Outsourcing physical education in schools: What and why do schools outsource to external providers? Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 4, 854617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strogilos, V., & Tragoulia, E. (2013). Inclusive and collaborative practices in co-taught classrooms: Roles and responsibilities for teachers and parents. Teaching and Teacher Education, 35, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šumanović, M., Tomac, Z., & Košutić, M. (2016). Primary school teachers’ attitudes about difficulties in physical education (PE). Croatian Journal of Education, 18(Sp.Ed.No.1), 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trenéři ve škole. (n.d.). Available online: www.treneriveskole.cz (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Trenéri v škole. (n.d.). Available online: www.trenerivskole.sk (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Truelove, S., Johnson, A. M., Burke, S. M., & Tucker, P. (2021). Comparing Canadian generalist and specialist elementary school teachers’ self-efficacy and barriers related to physical education instruction. Journal of Teaching in Physical Education, 40, 10–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. (2015). Quality physical education: Guidelines for policy-makers. UNESCO. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000231101 (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- UNESCO & Loughborough University. (2024). The global state of play: Report and recommendations on quality physical education. UNESCO. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000390593 (accessed on 23 July 2025).

- Van Garderen, D., Stormont, M., & Goel, N. (2012). Collaboration between general and special educators and student outcomes: A need for more research. Psychology in the Schools, 49, 483–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangrieken, K., Dochy, F., Raes, E., & Kyndt, E. (2015). Teacher collaboration: A systematic review. Educational Research Review, 15, 17–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, T. (2022). ‘Promoted widely but not valued’: Teachers’ perceptions of team teaching as a form of professional development in post-primary schools in Ireland. Professional Development in Education, 48(4), 688–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whipp, P., Hutton, H., Grove, J., & Jackson, B. (2011). Outsourcing Physical Education in primary schools: Evaluating the impact of externally provided programmes on generalist teachers. Asia-Pacific Journal of Health, Sport and Physical Education, 2(2), 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, B. J., & Macdonald, D. (2015). Explaining outsourcing in health, sport and physical education. Sport, Education and Society, 20(1), 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Slovakia | North Macedonia | |||

| Gender | Male | 10 | 93 | 103 |

| Female | 304 | 211 | 515 | |

| Total | 314 | 304 | 618 | |

| Slovakia | North Macedonia | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region | Teachers (n = 85) | Percentage (%) | Region | Teachers (n = 89) | Percentage (%) |

| Košicke region | 19 | 22.35 | Vardar region | 14 | 15.73 |

| Žilina region | 15 | 17.65 | East Region | 11 | 12.36 |

| Bratislava region | 12 | 14.12 | South–west region | 9 | 10.11 |

| Prešov region | 11 | 12.94 | South–east region | 12 | 13.48 |

| Banská Bystrica region | 10 | 11.76 | Pelagonia region | 12 | 13.48 |

| Nitra region | 7 | 8.24 | Polog region | 5 | 5.62 |

| Trenčín region | 6 | 7.06 | North–east region | 7 | 7.87 |

| Trnava region | 5 | 5.88 | Skopje region | 19 | 21.35 |

| Variable | Category | Slovakia | North Macedonia | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) 314 (50.8) | n (%) 304 (49.2) | n (%) 618 (100) | ||

| 1. Use of movement games at PE classes | Completely prepared | 124 (39.5) | 150 (49.3) | 274 (44.3) |

| Partially prepared | 136 (43.3) | 105 (34.5) | 241 (39.3) | |

| Not well prepared | 20 (6.4) | 29 (9.5) | 49 (7.9) | |

| I had previous experience in similar areas | 33 (10.5) | 20 (6.6) | 53 (8.6) | |

| Other | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) | |

| 2. Selection of activities and contents appropriate for children’s age and abilities | Completely prepared | 132 (42) | 168 (55.3) | 300 (48.5) |

| Partially prepared | 137 (43.6) | 90 (29.6) | 227 (36.7) | |

| Not well prepared | 25 (8) | 24 (7.9) | 49 (7.9) | |

| I had previous experience in similar areas | 19 (6.1) | 22 (7.2) | 41 (6.6) | |

| Other | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) | |

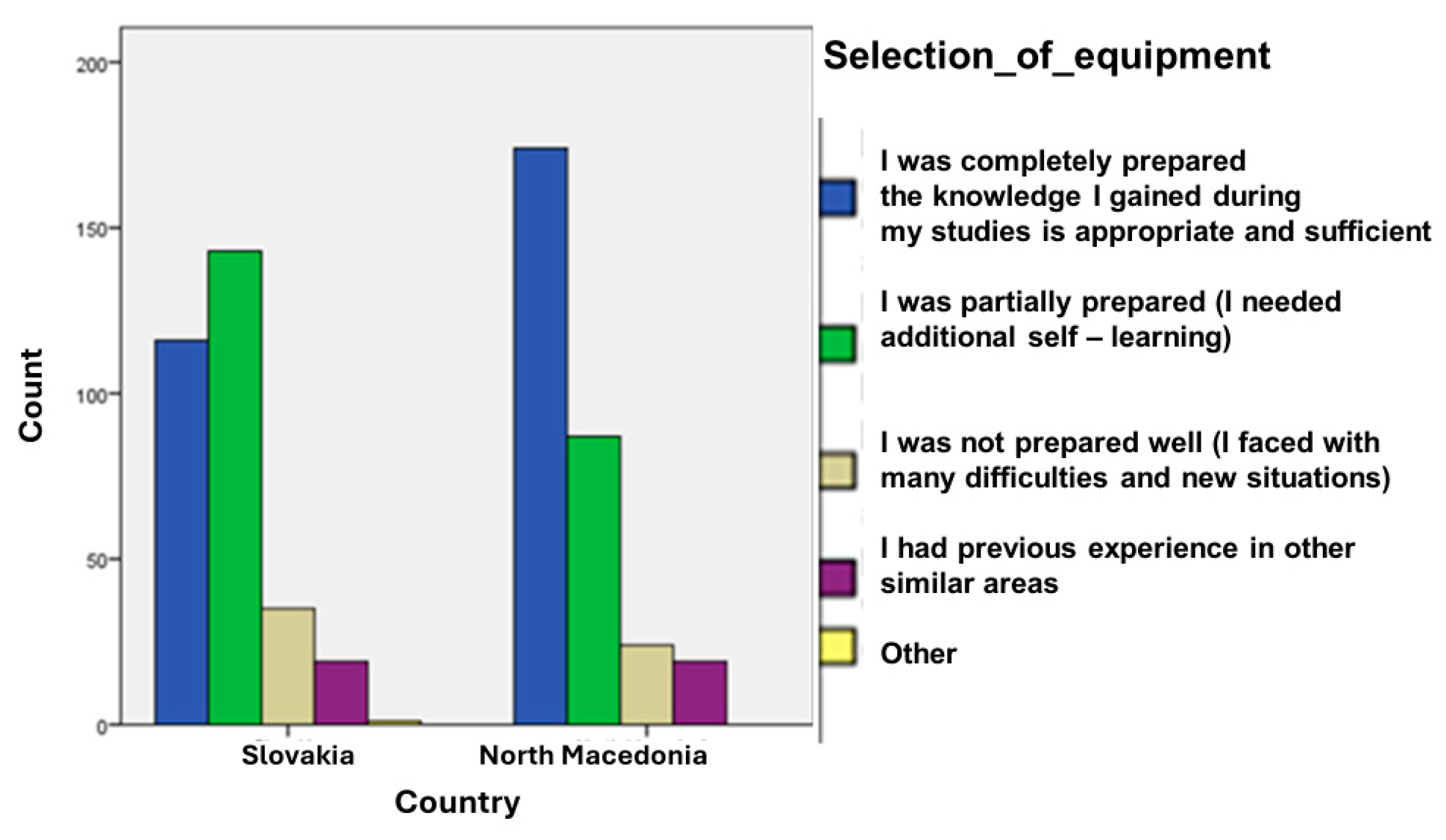

| 3. Selection of equipment appropriate for children’s age and abilities | Completely prepared | 116 (36.9) | 174 (57.2) | 290 (46.9) |

| Partially prepared | 143 (45.5) | 87 (28.6) | 230 (37.2) | |

| Not well prepared | 35 (11.1) | 24 (7.9) | 59 (9.5) | |

| I had previous experience in similar areas | 19 (6.1) | 19 (6.3) | 38 (6.1) | |

| Other | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) | |

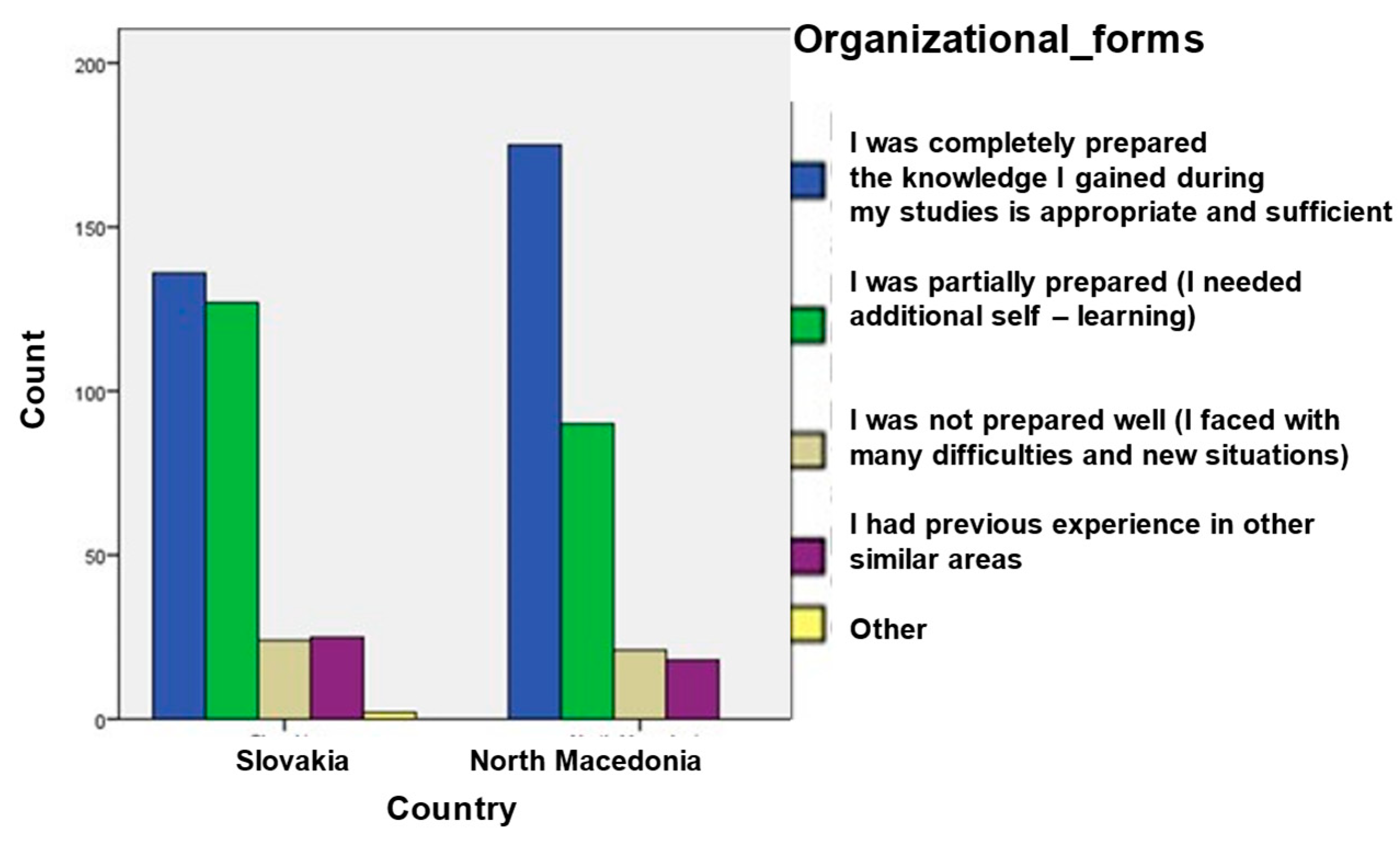

| 4. Choosing organizational forms according to students’ age and abilities | Completely prepared | 136 (43.3) | 175 (57.6) | 311 (50.3) |

| Partially prepared | 127 (40.4) | 90 (29.6) | 217 (35.1) | |

| Not well prepared | 24 (7.6) | 21 (6.9) | 45 (7.3) | |

| I had previous experience in similar areas | 25 (8.0) | 18 (5.9) | 43 (7.0) | |

| Other | 2 (0.6) | 0 (0) | 2 (0.3) | |

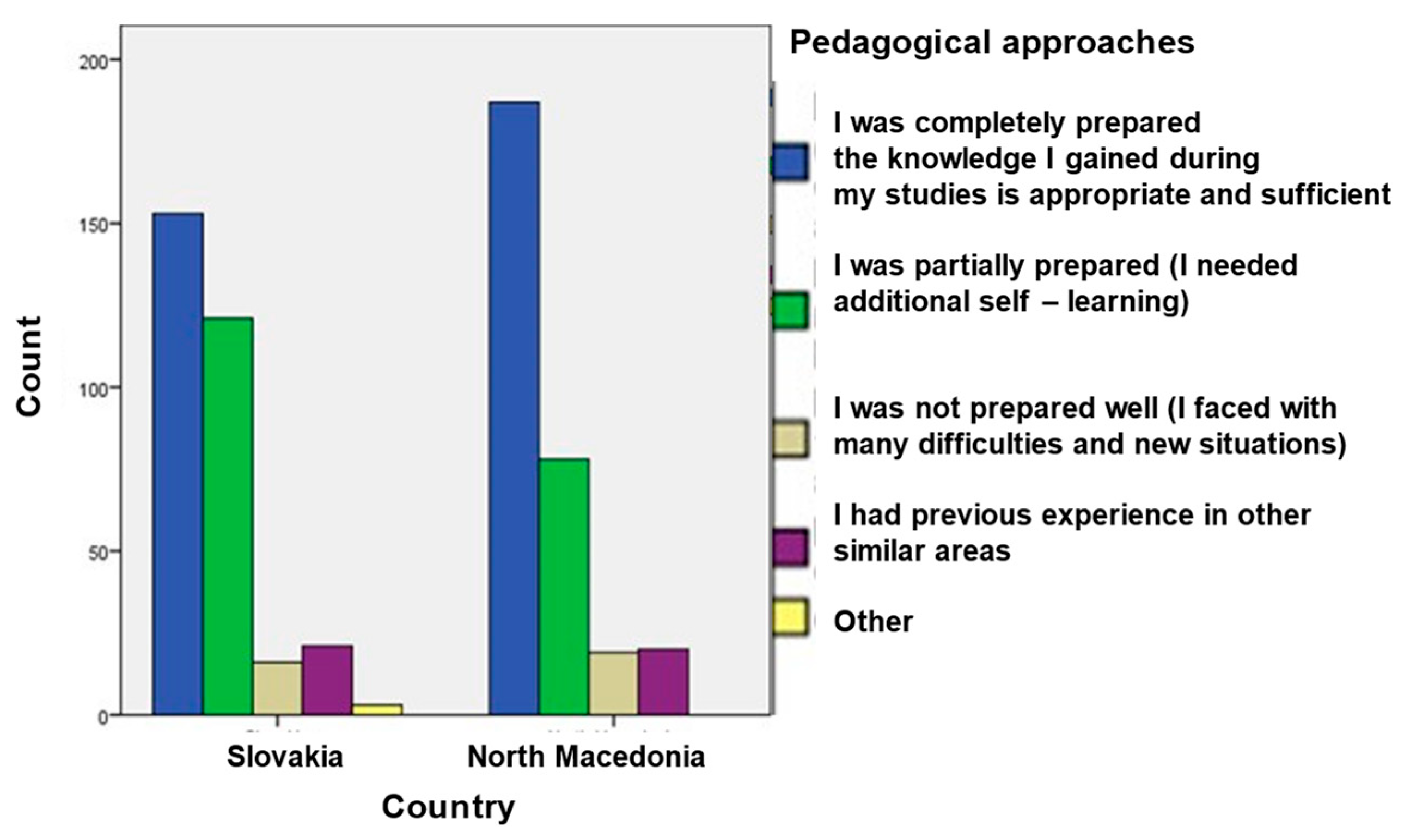

| 5. Pedagogical approaches appropriate for working with children at younger age | Completely prepared | 153 (48.7) | 187 (61.5) | 340 (55.0) |

| Partially prepared | 121 (38.5) | 78 (25.7) | 199 (32.2) | |

| Not well prepared | 16 (5.1) | 19 (6.3) | 35 (5.7) | |

| I had previous experience in similar areas | 21 (6.7) | 20 (6.6) | 41 (6.6) | |

| Other | 3 (1.0) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.5) | |

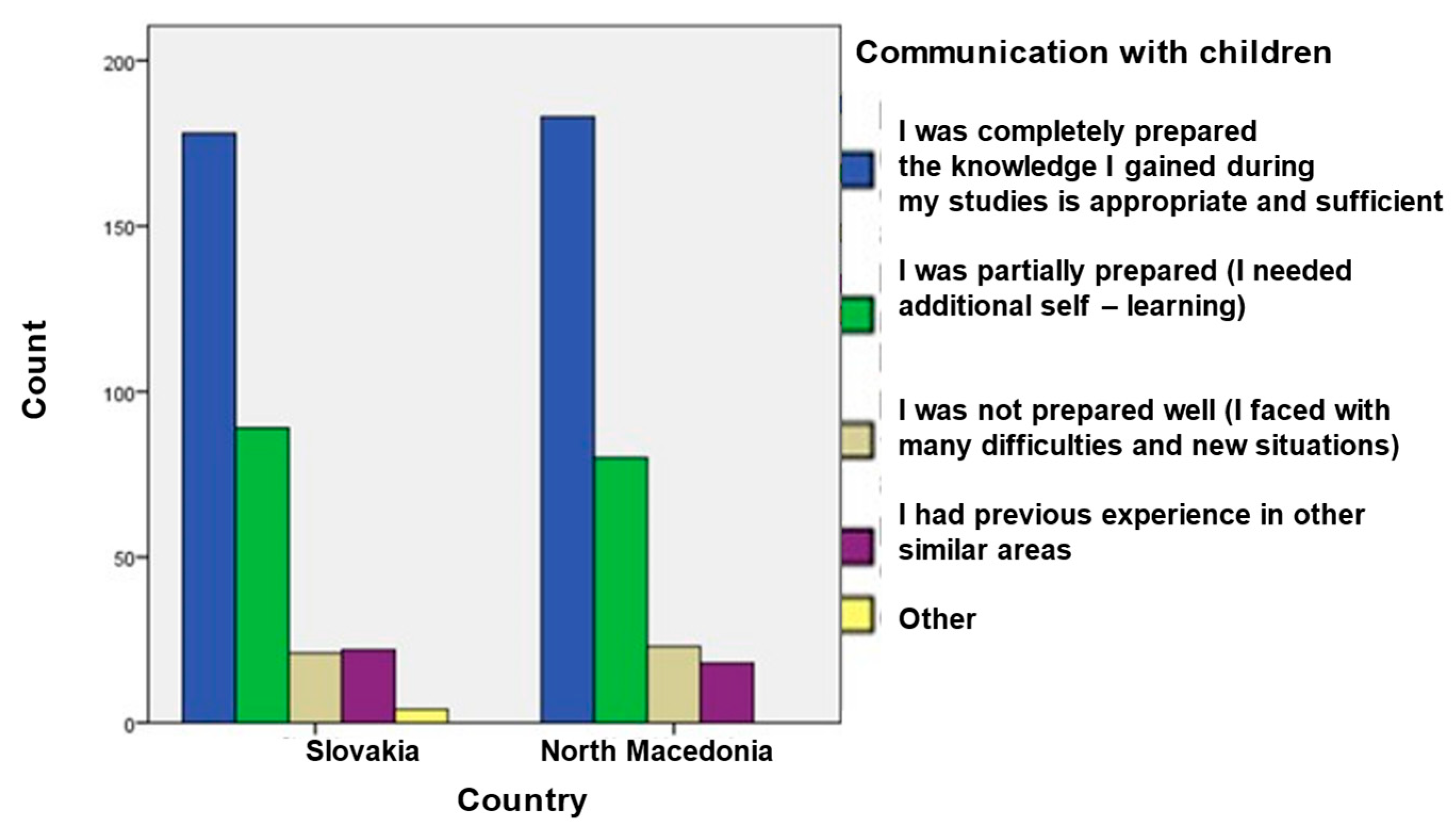

| 6. Communication with children in early school period | Completely prepared | 178 (56.7) | 183 (60.2) | 361 (58.4) |

| Partially prepared | 89 (28.3) | 80 (26.3) | 169 (27.3) | |

| Not well prepared | 21 (6.7) | 23 (7.6) | 44 (7.1) | |

| I had previous experience in similar areas | 22 (7.0) | 18 (5.9) | 40 (6.5) | |

| Other | 4 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 4 (0.6) | |

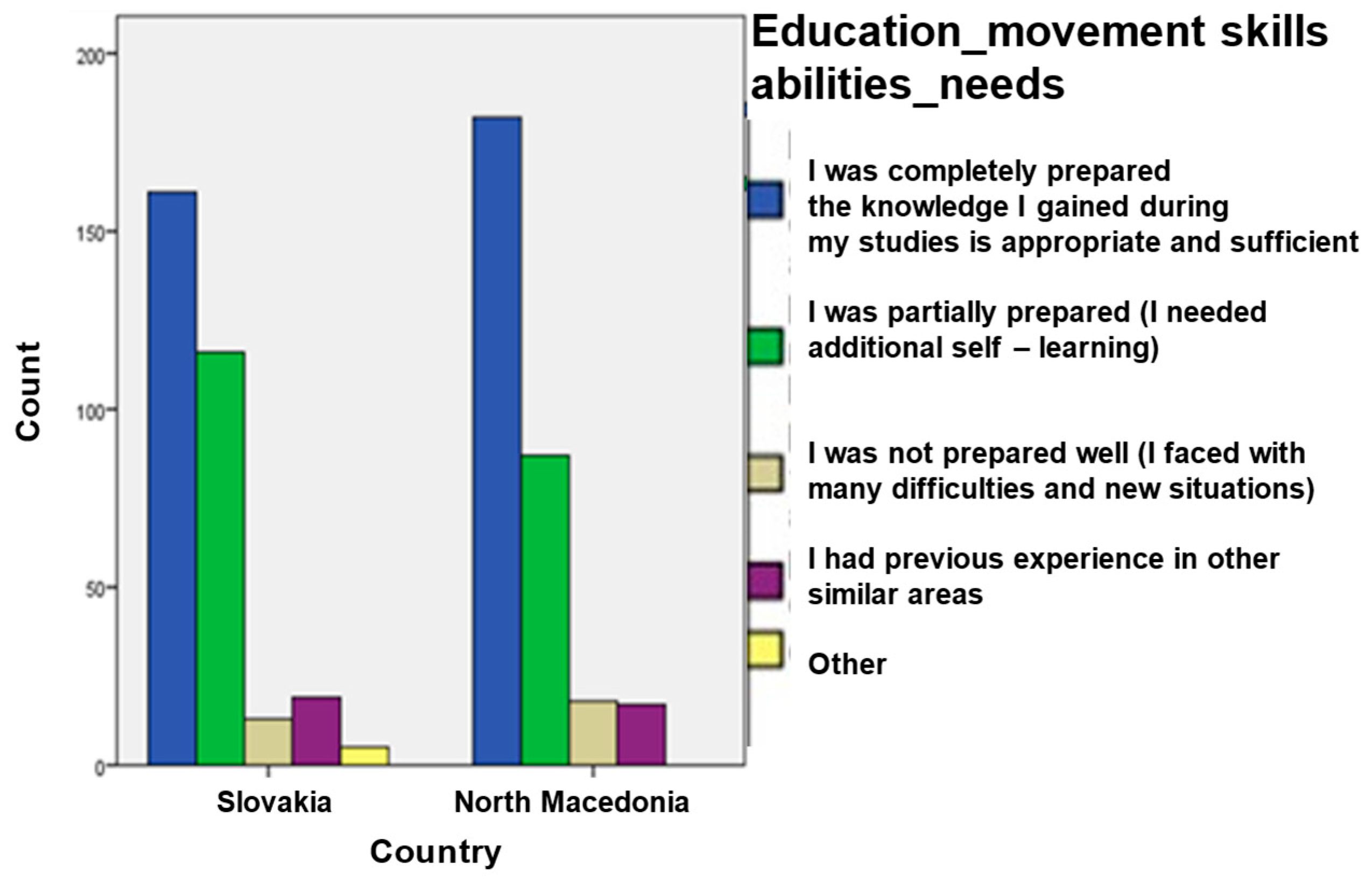

| 7. Movement skills, abilities and needs of children in early-school period | Completely prepared | 161 (51.3) | 182 (59.9) | 343 (55.5) |

| Partially prepared | 116 (36.9) | 87 (28.6) | 203 (32.8) | |

| Not well prepared | 13 (4.1) | 18 (5.9) | 31 (5.0) | |

| I had previous experience in similar areas | 19 (6.1) | 17 (5.6) | 36 (5.8) | |

| Other | 5 (1.6) | 0 (0) | 5 (0.8) | |

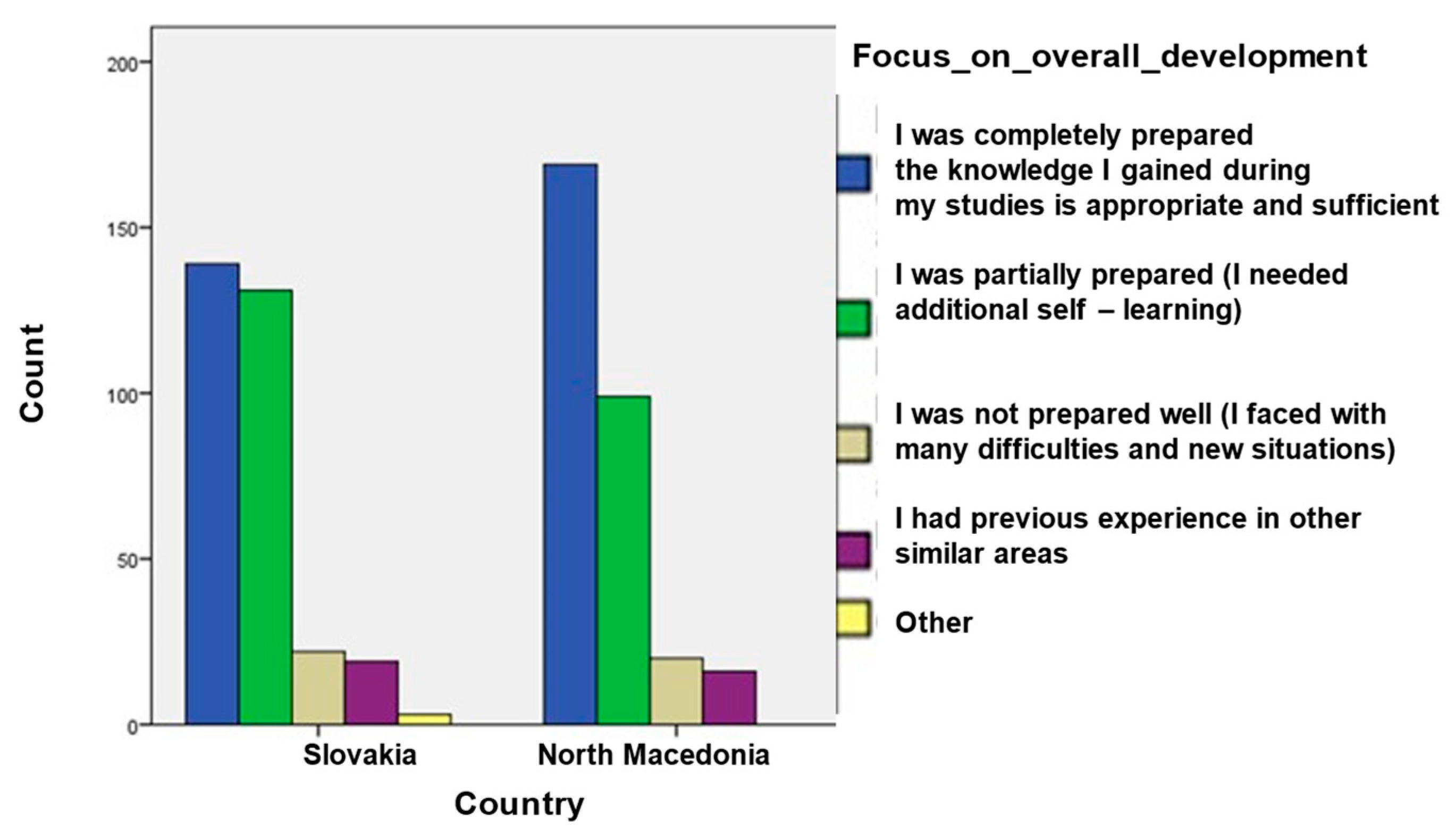

| 8. Approach focused on overall development, not just on development of movement skills | Completely prepared | 139 (44.3) | 169 (55.6) | 308 (49.8) |

| Partially prepared | 131 (41.7) | 99 (32.6) | 230 (37.2) | |

| Not well prepared | 22 (7.0) | 20 (6.6) | 42 (6.8) | |

| I had previous experience in similar areas | 19 (6.1) | 16 (5.3) | 35 (5.7) | |

| Other | 3 (1.0) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.5) | |

| 9. Work with children with diverse learning needs | Completely prepared | 79 (25.2) | 91 (29.9) | 170 (27.5) |

| Partially prepared | 119 (37.9) | 120 (39.5) | 239 (38.7) | |

| Not well prepared | 81 (25.8) | 76 (25.0) | 157 (25.4) | |

| I had previous experience in similar areas | 24 (7.6) | 17 (5.6) | 41 (6.6) | |

| Other | 11 (3.6) | 0 (0) | 11 (1.8) | |

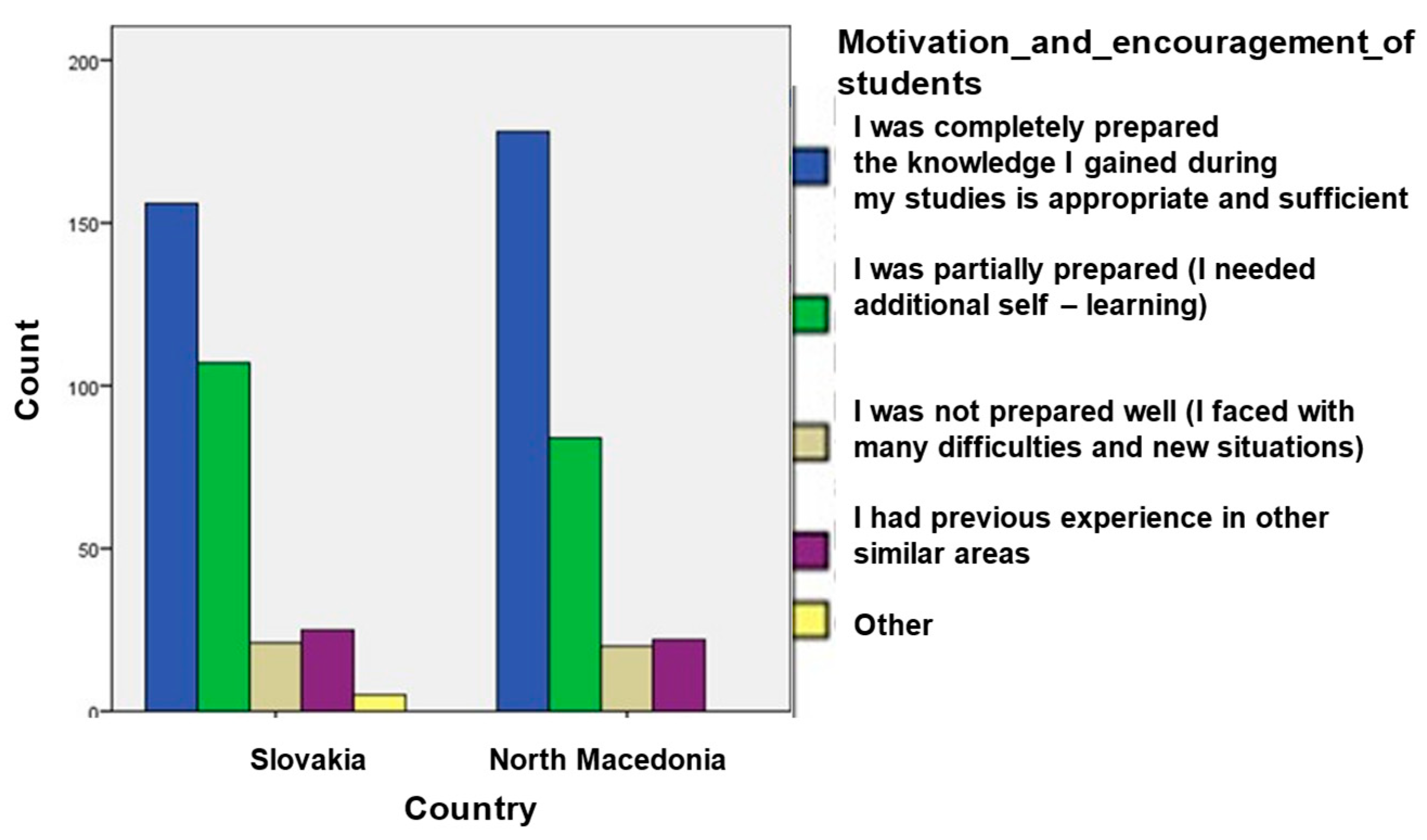

| 10. Motivation and encouragement of students | Completely prepared | 156 (49.7) | 178 (58.6) | 334 (54.0) |

| Partially prepared | 107 (34.1) | 84 (27.6) | 191 (30.9) | |

| Not well prepared | 21 (6.7) | 20 (6.6) | 41 (6.6) | |

| I had previous experience in similar areas | 25 (8.0) | 22 (7.2) | 47 (7.6) | |

| Other | 5 (1.6) | 0 (0) | 5 (0.8) | |

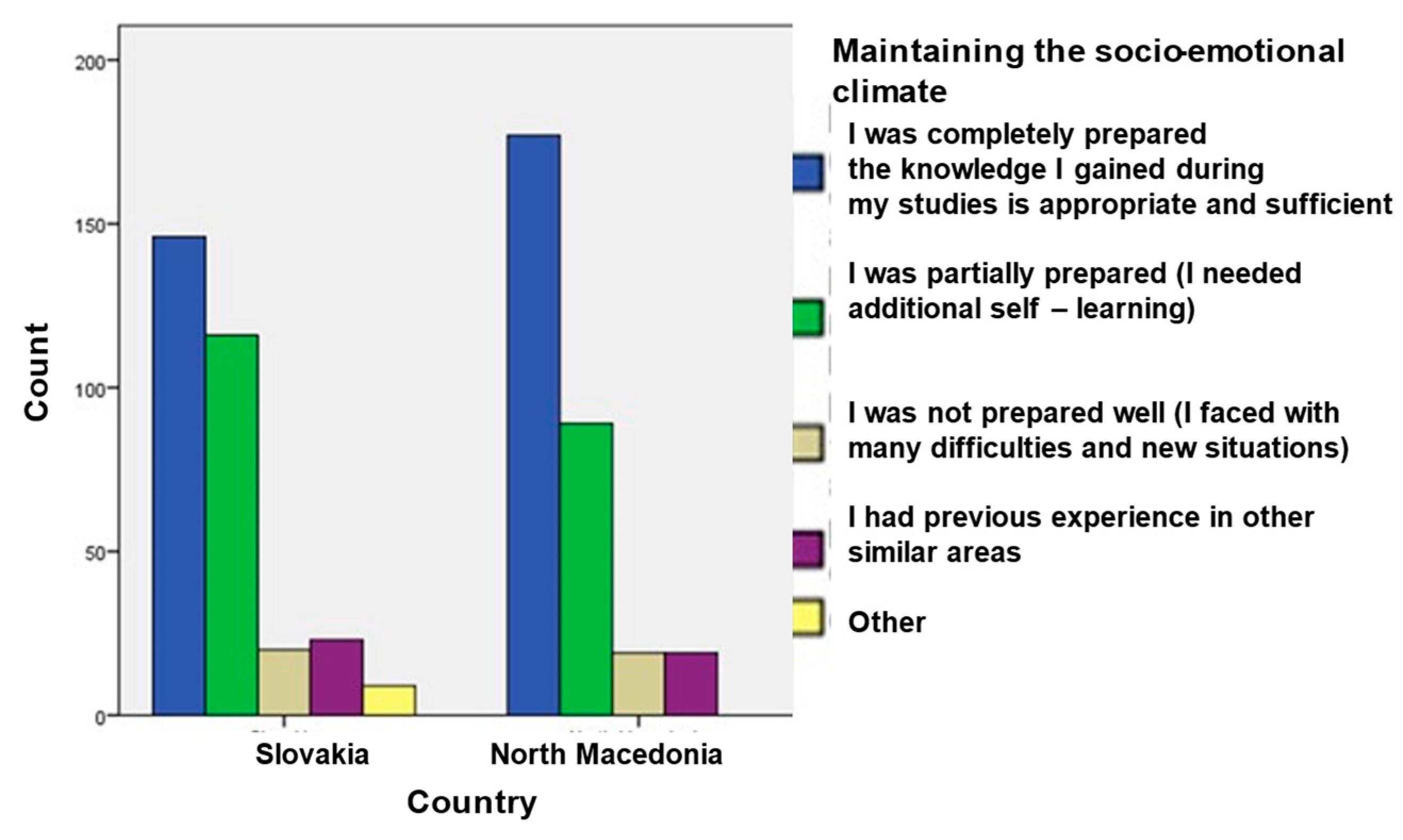

| 11. Maintaining the socio-emotional climate in the class during PE lessons | Completely prepared | 146 (46.5) | 177 (58.2) | 323 (52.3) |

| Partially prepared | 116 (36.9) | 89 (29.3) | 205 (33.2) | |

| Not well prepared | 20 (6.4) | 19 (6.3) | 39 (6.3) | |

| I had previous experience in similar areas | 23 (7.3) | 19 (6.3) | 42 (6.8) | |

| Other | 9 (2.9) | 0 (0) | 9 (1.5) |

| Variable | Pearson Chi-Square (N) | df | p-Value | Cramér’s V | Association Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Use of movement games at PE classes | 12.138 (618) | 4 | 0.016 | 0.140 | Weak |

| 2. Selection of activities and contents appropriate for children’s age and abilities | 15.133 (618) | 4 | 0.004 | 0.156 | Weak |

| 3. Selection of equipment appropriate for children’s age and abilities | 28.131 (618) | 4 | 0.000 | 0.213 | Weak |

| 4. Choosing organizational forms according to students’ age and abilities | 14.381 (618) | 4 | 0.006 | 0.153 | Weak |

| 5. Pedagogical approaches appropriate for working with children at younger age | 15.815 (618) | 4 | 0.003 | 0.160 | Weak |

| 6. Communication with children in early school period | 4.879 (618) | 4 | 0.300 | 0.089 | Weak |

| 7. Movement skills, abilities and needs of children in early-school period | 11.187 (618) | 4 | 0.025 | 0.135 | Weak |

| 8. Approach focused on overall development and not just on development of movement skills | 10.568 (618) | 4 | 0.032 | 0.131 | Weak |

| 9. Work with children with diverse learning needs | 13.047 (618) | 4 | 0.011 | 0.145 | Weak |

| 10. Motivation and encouragement of students | 9.275 (618) | 4 | 0.055 | 0.123 | Weak |

| 11. Maintaining the socio-emotional climate in the class during PE lessons | 15.780 (618) | 4 | 0.003 | 0.160 | Weak |

| Options | Slovakia n (%) | North Macedonia n (%) | Total n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

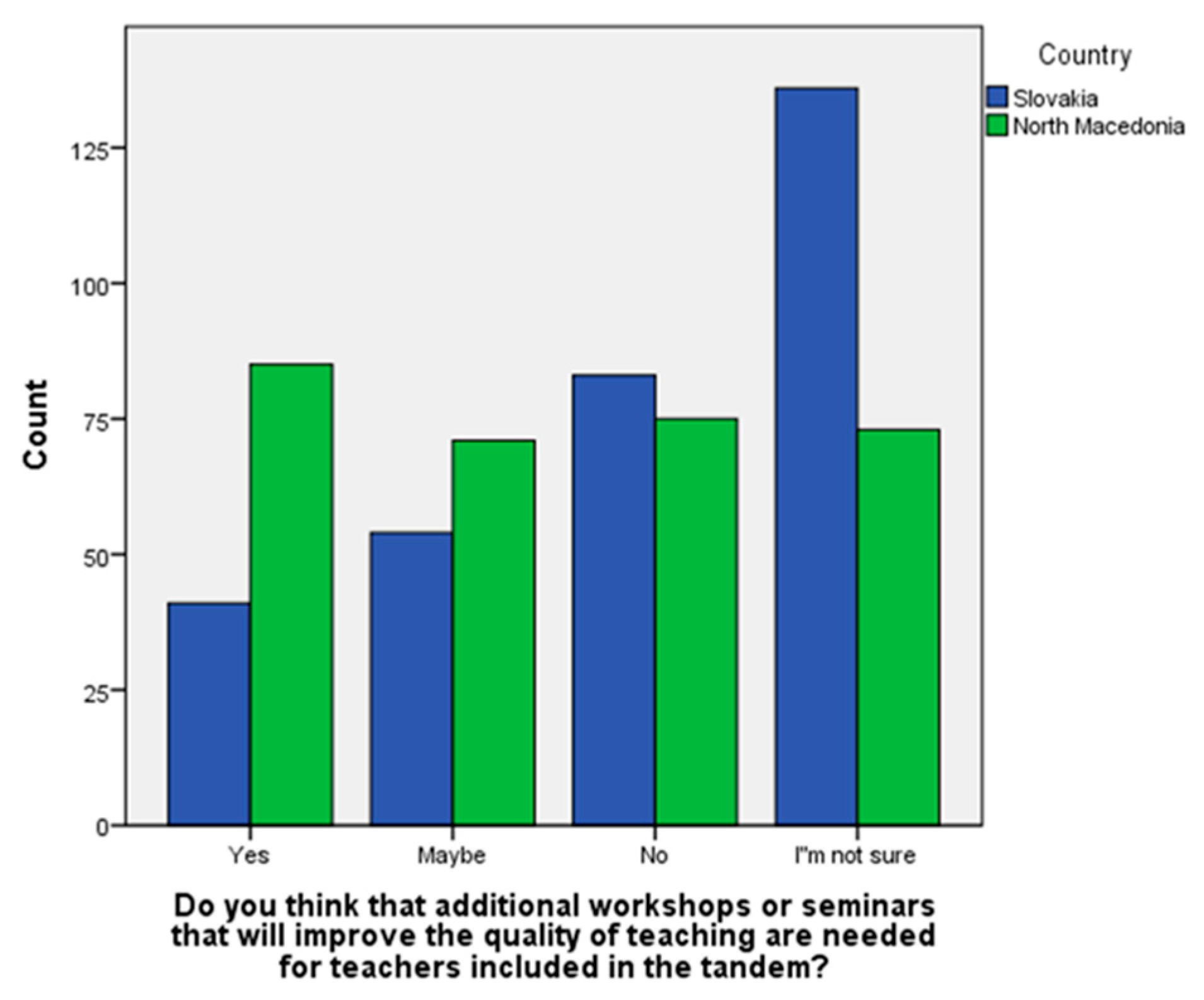

| Do you think that additional workshops or seminars that will improve the quality of teaching are needed for teachers included in the tandem? | Yes | 41 (13.06) | 85 (27.96) | 126 |

| Maybe | 54 (17.20) | 71 (23.36) | 125 | |

| No | 83 (26.43) | 75 (24.67) | 158 | |

| I’m not sure | 136 (43.31) | 73 (24.01) | 209 | |

| 314 (50.8) | 304 (49.2) | 618 |

| Topic | Content | |

|---|---|---|

| Overarching topics | Work with Specific Student Groups | Working with students with diverse learning needs (gifted abilities, learning disabilities, special educational needs). |

| Methodology and Didactics | Improving teaching methods—learning how to create more interactive lessons, manage larger classes effectively, managing PE classes in small spaces or in the classroom, managing PE classes with limited resources and equipment reflection, create a positive and safe classroom environment, new approaches in PE lessons | |

| Communication and Collaboration | Improving communication skills of teachers, learning communication strategies between tandem teachers, with students and parents, strategies for effective teamwork with colleagues. | |

| Specific Subject Matters and holistic learning through PE | Workshops tailored to integrate learning content between PE and other specific subjects (Math, Languages, Music, Art), focusing on innovative teaching strategies for those disciplines | |

| Country-specific topics | ||

| Slovakia | Student Well-being and Mental Health | Managing stress, addressing burnout in both students and teachers, and supporting students with mental health challenges |

| Digital Skills and Technology | Focus on using apps and AI tools, creating effective teaching materials, and using various digital platforms. | |

| North Macedonia | Movement games and sport-based activities | Age-appropriate movement games for different phases of PE lessons, classroom-based movement games, outdoor based movement games and activities, cooperation games, fun and engaging activities |

| Efficient organization of tandem teaching | Seminars for efficient organization of tandem teaching, distribution of tasks and responsibilities, effective communication between teachers. | |

| New approaches in teaching PE | Workshops and seminars for updates with new trends in teaching PE and sport pedagogy, experiences from other countries and teachers, practical workshops with teachers | |

| Supporting materials | Design of manuals, handbooks and other teaching materials and handbooks that will support teachers work in the tandem | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Luptáková, G.; Popeska, B.; Ristevska, H.; Balga, T.; Klincarov, I.; Antala, B. Tandem Teaching for Quality Physical Education: Primary Teachers’ Preparedness and Professional Growth in Slovakia and North Macedonia. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1397. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101397

Luptáková G, Popeska B, Ristevska H, Balga T, Klincarov I, Antala B. Tandem Teaching for Quality Physical Education: Primary Teachers’ Preparedness and Professional Growth in Slovakia and North Macedonia. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1397. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101397

Chicago/Turabian StyleLuptáková, Gabriela, Biljana Popeska, Hristina Ristevska, Tibor Balga, Ilija Klincarov, and Branislav Antala. 2025. "Tandem Teaching for Quality Physical Education: Primary Teachers’ Preparedness and Professional Growth in Slovakia and North Macedonia" Education Sciences 15, no. 10: 1397. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101397

APA StyleLuptáková, G., Popeska, B., Ristevska, H., Balga, T., Klincarov, I., & Antala, B. (2025). Tandem Teaching for Quality Physical Education: Primary Teachers’ Preparedness and Professional Growth in Slovakia and North Macedonia. Education Sciences, 15(10), 1397. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101397