Exploring the Use of AI to Optimize the Evaluation of a Faculty Training Program

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Faculty Training in Spain

1.2. Evaluating Training Programs in Higher Education

1.3. The Use of ChatGPT to Support Qualitative Analysis: Potential, Limitations and Hybrid Approaches

- To analyze survey responses evaluating the initial teacher training program offered by ICE, with the aim of identifying critical areas and recurring issues and assisted by ChatGPT.

- To explore the root causes of the identified critical aspects through thematic grouping and visual organization into a cause-and-effect diagram, assisted by ChatGPT.

- To propose strategic solutions and concrete actions by compiling a table that links each identified issue with potential interventions, assisted by ChatGPT.

- To formulate student-based recommendations to address the program’s deficiencies, serving as a basis for discussion by the faculty development team, assisted by ChatGPT.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Context and Methodological Framework

2.2. Participants and Sampling

2.3. Data Collection

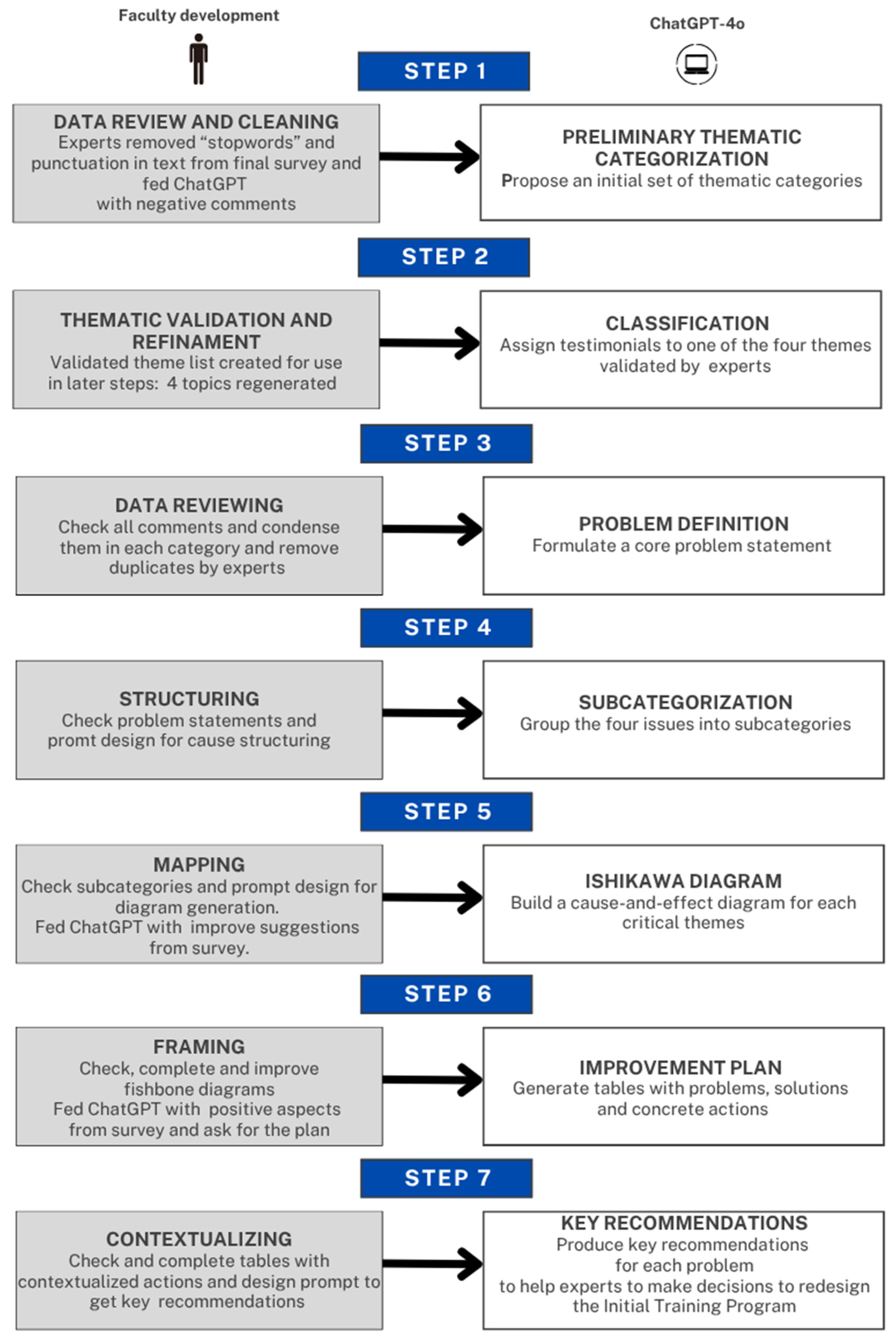

2.4. Data Analysis

2.4.1. Step 1. Data Preprocessing

2.4.2. Step 2. Theme Validation

2.4.3. Step 3. Problem Definition

2.4.4. Step 4. Subcategorization of Main Problems

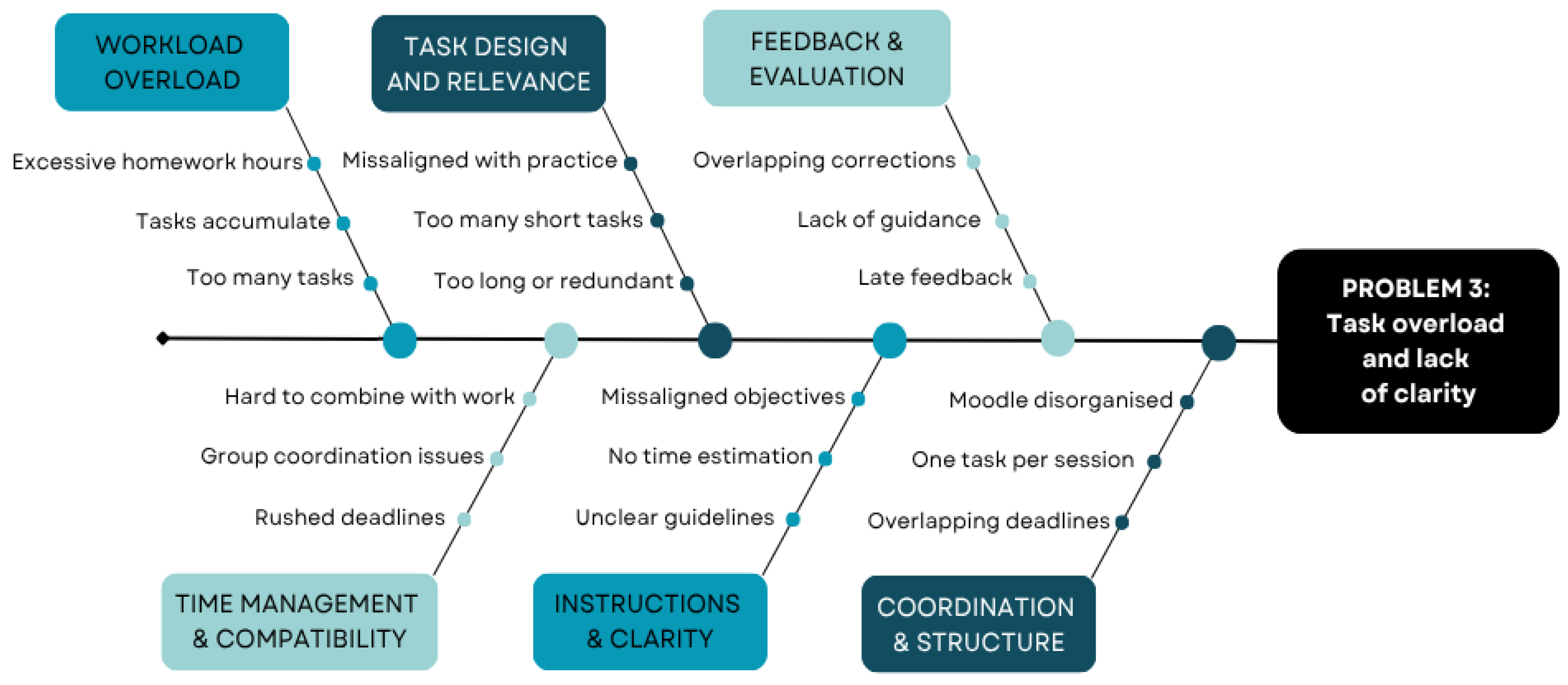

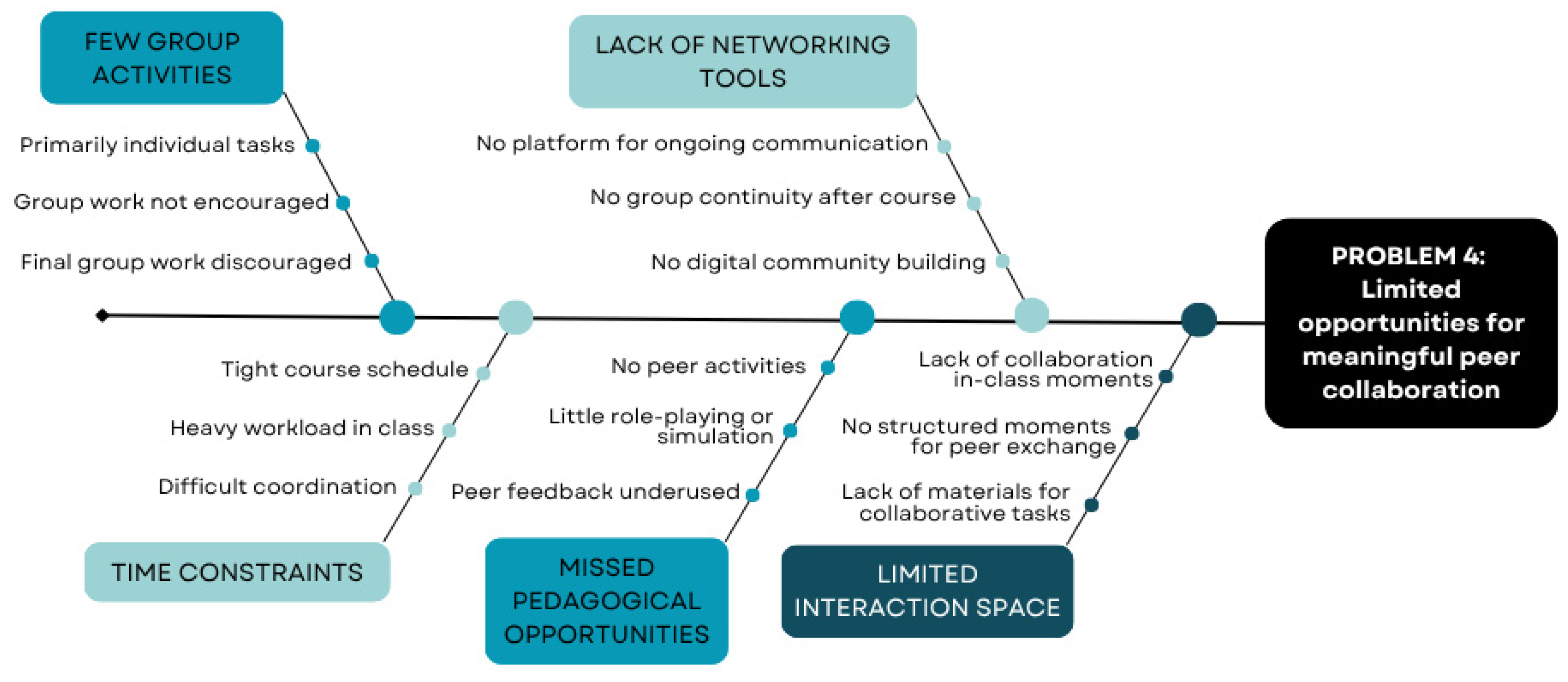

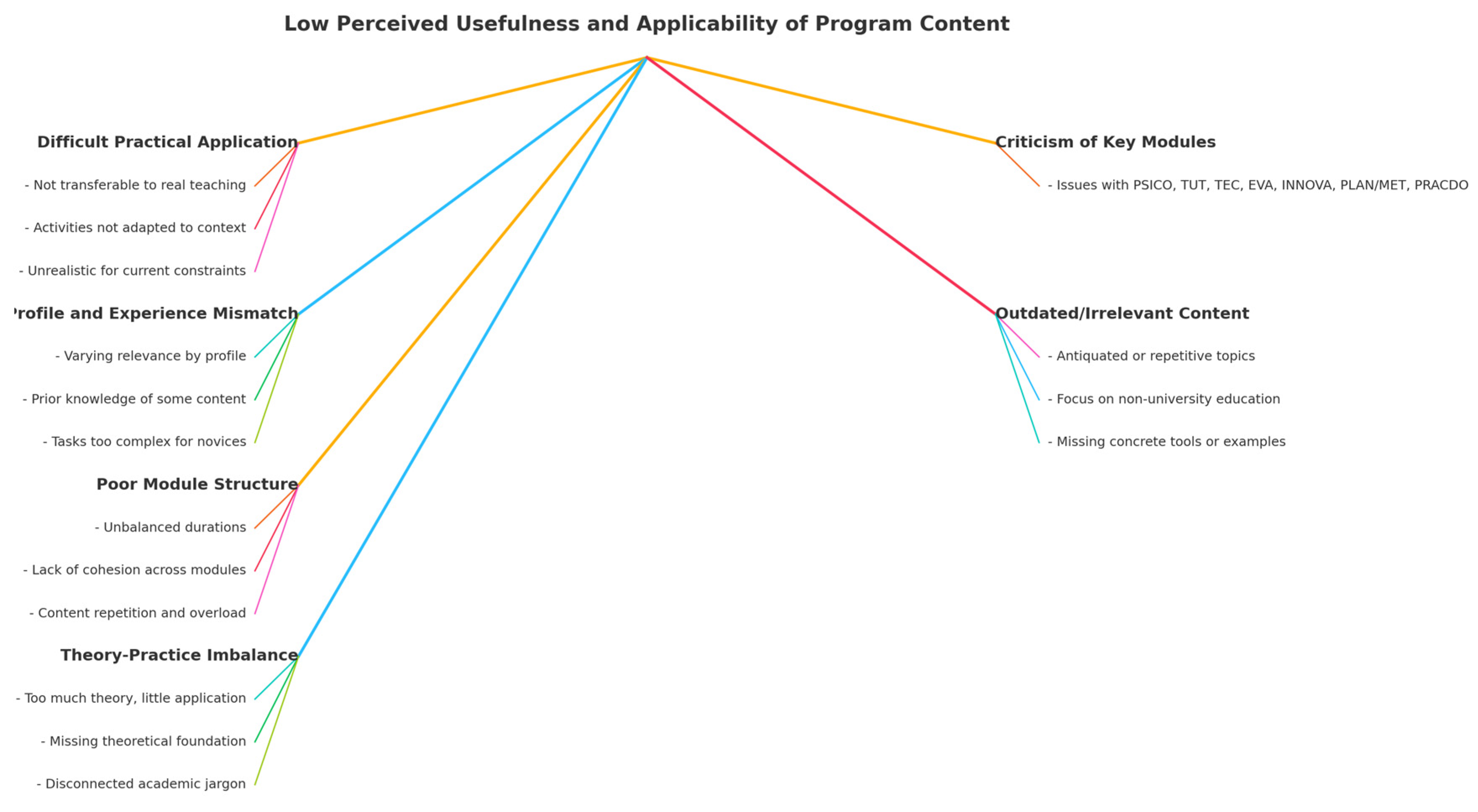

2.4.5. Step 5. Visual Mapping

2.4.6. Step 6. Solution Design

2.4.7. Step 7. Recommendations Extraction

3. Results

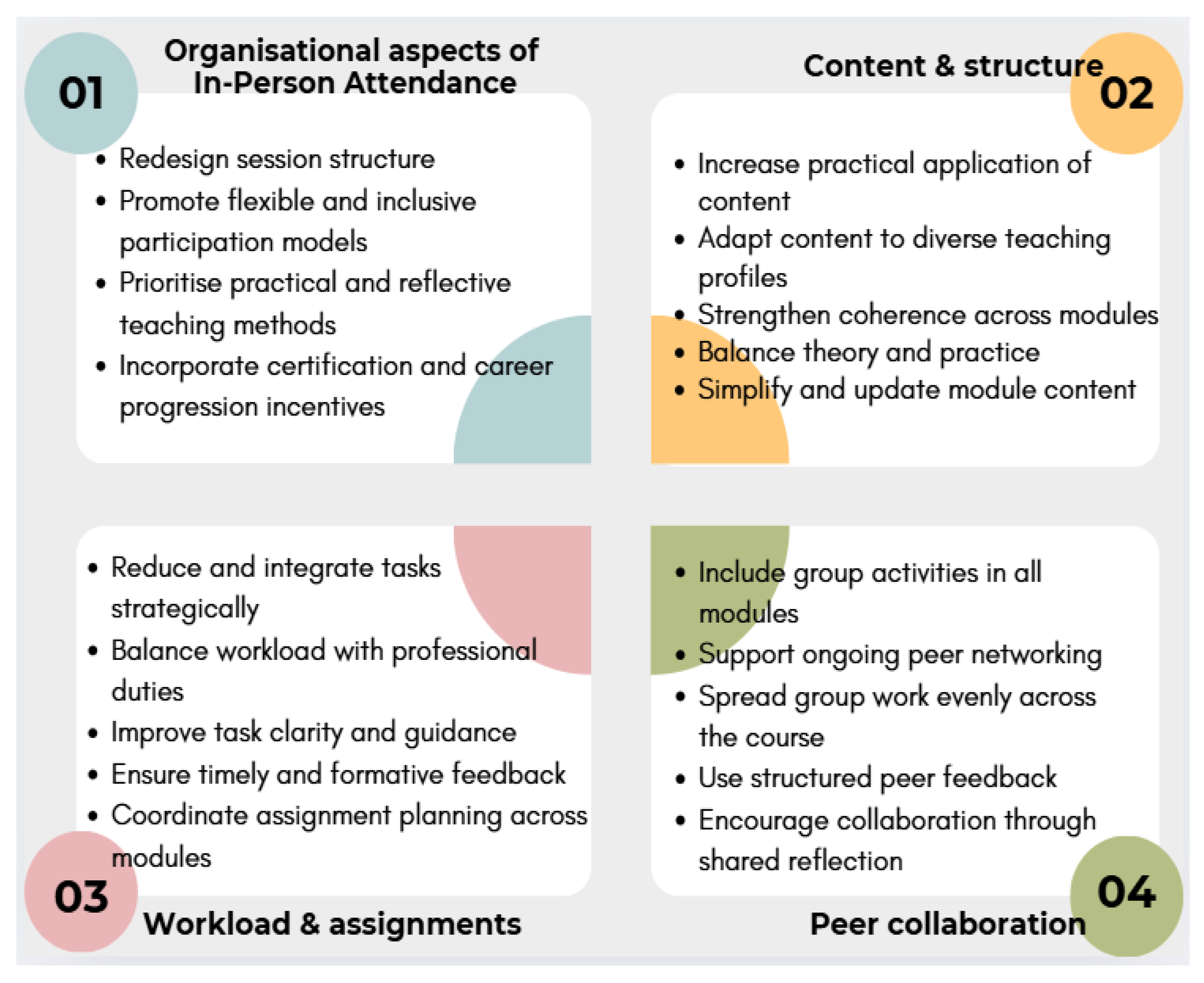

3.1. Critical Areas and Recurring Issues of the Initial Teacher Training Program

- Organizational aspects of in-person attendance.

- Content and structure.

- Workload and assignments.

- Peer collaboration.

3.2. Root Causes of the Critical Aspects and Cause-and-Effect Diagram

3.3. Strategic Solutions and Concrete Actions for Each Problem

3.4. Student-Based Prioritized Recommendations to Address the Program’s Deficiencies

- Reduce and Integrate Tasks Strategically:

- Limit the number of assignments per module.

- Merge related tasks into one comprehensive assignment.

- Focus on tasks with high practical relevance, such as designing rubrics or lesson plans.

- Balance Workload with Professional Duties:

- Allow flexible deadlines and extended submission windows.

- Integrate task completion time into in-person sessions when possible.

- Provide alternatives for group work to accommodate varying schedules.

- Improve Task Clarity and Guidance:

- Provide clear instructions, time estimates, and example submissions.

- Link each task explicitly to learning outcomes or module objectives.

- Use standardized templates and rubrics across modules.

- Ensure Timely and Formative Feedback:

- Set maximum time limits for returning feedback (e.g., 2 weeks).

- Offer feedback opportunities during in-class sessions or via peer review.

- Incorporate guided self-assessment as part of the learning process.

- Coordinate Assignment Planning Across Modules:

- Create and share a unified calendar of all course deadlines.

- Avoid overlapping submission dates between modules.

- Organize Moodle task areas consistently to reduce confusion.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Patents

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UPM | Polytechnic University of Madrid |

| ICE | Institute of Educational Sciences |

| PLAN | Teaching planning module |

| MET | University teaching methods |

| TEC | Learning technologies |

| EVA | Assessment |

| TUT | Student guidance |

| PSICO | University organization and applied psychology |

| INNOVA | Educational innovation |

| PRACDO | Classroom practice and communication techniques |

Appendix A

| COURSE EVALUATION SURVEY Initial Training for University Teaching | ||

| Polytechnic University of Madrid (UPM) · Institute of Educational Sciences (ICE) | ||

| Academic Year 20XX– 20XX | ||

| Below are some questions about the Initial Training course you have completed. Please answer all of them honestly. There are no right or wrong answers; we want to know your opinion. Thank you very much for your participation! | ||

| Write in or mark with an “X” the appropriate response. | ||

| Gender: | □ Male | □ Female |

| Age: _____ | Years of University Teaching Experience: _____ | |

| Field of Knowledge: | ||

| □ Health Sciences | □ Sciences | |

| □ Arts and Humanities | □ Social and Legal Sciences | |

| □ Physical Education | □ Engineering/Architecture/Computer Science | |

| Professional Category: | ||

| □ Predoctoral Researcher | □ Postdoctoral Researcher | |

| □ Assistant Lecturer | □ Doctoral Assistant Lecturer | |

| □ Contracted Doctor | □ Interim Associate Professor | |

| □ Associate Professor | □ Other: _______________ | |

| Circle the response that best applies on a scale from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 6 (Strongly Agree). | Strongly disagree | Strongly agree | |||||

| |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| |||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| |||||||

| 6.1. In your opinion, it should be organized as: | |||||||

| □ Fully face-to-face | □ More face-to-face | ||||||

| □ As it is | □ More online | □ Fully online | |||||

| Very little | Very much | |||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

| |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

Appendix B

Appendix C

- Ishikawa Diagrams Breaking Down Each Main Problem into Specific Causes

Appendix D

- General Solutions and Specific Actions Proposed by ChatGPT to Tackle the Four Problems

| Main Problem 1 *: “Students Consider the In-Person Sessions Inefficient” | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Subcategory | Problem | Strategic Solutions | Specific Actions |

| Evaluation and attendance | Attendance requirement is too high (75%) | Offer flexible attendance through hybrid and asynchronous alternatives | Allow students to complete part of the course asynchronously through Moodle forums and assignments. Reduce the 75% attendance requirement. Allow alternatives to mandatory attendance such as evaluative activities or forum participation assignments. |

| Demotivating grading system linked to attendance | Implement competency-based assessment with formative feedback | Introduce competency-based grading with rubrics, self-assessment, and peer feedback. Reduce dependency on attendance as a grading factor. | |

| Course structure and scheduling | Sessions are too long (exceed four hours) | Reduce session duration and space sessions out | Limit sessions to a maximum of three hours. Space sessions out across the semester. Offer modular or two-semester formats to balance workload and certification needs. Alternate weeks classes with self-study to prevent overload. |

| Sessions are scheduled too frequently to meet ECTS requirements | Reorganize the course schedule to balance in-person and asynchronous activities | Space sessions strategically across the semester. Restructure the course into two semesters, offering a mid-year certification to support agencies accreditation. | |

| Teaching methodology and student engagement | Too much theory, not enough practice | Prioritize practical learning | Avoid passive theory-heavy blocks. Adopt problem-based learning and expert-led workshops. Incorporate practical activities: microteaching, case studies with real examples, peer collaboration and feedback, role-playing, etc. Invite guest experts to share real-world teaching experiences. |

| Inefficient teaching techniques | Implementing active learning strategies | ||

| Digitalization and use of resources | Excessive paper-based documentation | Optimize the use of digital resources and promote paperless policies | Minimize the use of printed materials by transitioning to a fully digital format. Printed handouts should be provided only when strictly necessary. |

| Poor Moodle content organization | Standardize and organize Moodle course content into a clear and consistent structure | Standardize the structure of all Moodle course modules. Ensure consistent use of themes, materials and sections across modules. Organize the grading section for transparency and usability. Digitize all course documentation. Promote a fully paperless learning environment wherever possible. | |

| Flexibility and accessibility | Hard to balance with professional work | Offer hybrid formats and modular course structures | Provide modular course options so teachers can progress at their own pace. Offer alternative schedules to fit their professional duties. |

| No hybrid/online option for those who cannot attend in person | Offer hybrid formats with asynchronous participation options | Introduce a hybrid format with recorded key sessions available online. Record sessions and allow flexible completion through Moodle-based activities. Support those with heavy teaching loads with flexible, blended participation. | |

| Course recognition and motivation | Lack of professional incentives or certification value | Integrate the course into a modular master’s program | Integrate the course into a modular postgraduate program with official credit and recognition: Certify the training as part of a structured Master’s track, offering interim credentials and aligning it with UPM’s accreditation systems. Establish the course as a formal requirement for new faculty, reinforcing its role in academic career progression. |

| Demotivating grading system (Pass/fail) | Implement a traditional grading system | Adopt a standard letter-grade system (F to A) to reflect a student’s performance. | |

| Main Problem 2: “Low Perceived Usefulness and Applicability of Program Content” | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Problems | General Solutions * | Specific Actions |

| Difficult practical application | Not transferable to real teaching practice | Increase connection with teaching practice including more classroom-tested strategies | Include activities directly applicable to real subjects, with contextualized and real cases. Redesign modules to include more hands-on activities, simulations, real case studies, and examples directly applicable to university teaching contexts. |

| Activities not adapted to context | Design specific tasks for university environments, connecting tasks to real teaching experiences | Differentiate tasks according to teaching profile and real teaching subjects. | |

| Unrealistic for current constraints | Make realistic and scalable proposals by adapting activities to various disciplines and teaching scenarios | Provide examples adapted to large classes or limited resources. Design tasks grounded in participants’ real teaching contexts. | |

| Profile and experience mismatch | Varying relevance by profile | Make the program design more flexible, design leveled content paths | Offer differentiated pathways based on faculty level teaching experience. Adapt content and tasks to different levels of teaching experience and disciplinary backgrounds by providing alternative routes or task options based on participants’ roles and expertise. |

| Prior knowledge required for some content | Ensure leveling or base support for participants | Create optional or elective pathways according to previous experience and individual needs. Provide introductory materials or bridge modules for teachers without prior teaching experience. | |

| Contents are too complex for novices | Adapt the level of task difficulty | Offer graded or progressive versions of tasks based on experience level. Include step-by-step guides to support completion. | |

| Poor module structure | Unbalanced durations | Reorganize the duration of content modules to better match their workload | Reduce or adjust the length of less valued modules: student guidance (TUT), university organization and applied psychology (PSICO). Expand classroom practice and communication techniques (PRACDOs). |

| Lack of cohesion across modules | Improve coordination among teachers and promote more instructional design consistency | Stable teaching teams for each thematic module. Improve the logical sequence of contents. Strengthen connections among modules to avoid repetition, overload, or inconsistencies in terminology and focus. | |

| Content repetition and overload | Review the sequence of modules and eliminate overlaps | Streamline overlapping content to remove redundancies and better balance the theoretical and practical workload. | |

| Theory- practice imbalance | Too much theory, little application * | Reversing the teaching approach to integrate theory with hands-on tasks | Apply the flipped classroom model: theory as reading, practice in class. Dedicate face-to-face time to project design, peer learning, or classroom simulations. Use classroom time for active learning, not lecturing. |

| Missing theoretical foundation | Balancing theory and practice through offering real-life examples from university teaching | Introduce brief, clear and practical fundamentals. Combine theory with micro-workshops or hands-on activities. | |

| Incomprehensible pedagogical jargon | Clarify pedagogical concepts with concrete examples | Use a teaching glossary and link terms to their use in the university classroom. Align theoretical concepts across modules with consistent vocabulary and complementary timing and reinforce key ideas across sessions. | |

| Outdated and irrelevant content | Antiquated or repetitive topics | Update content and focus regularly | Update content with current references. Review content to avoid redundancy and outdated materials, ensure clarity, and provide context-specific examples, especially in modules like TEC, PSICO, and INNOVA. |

| Focus on non-university education | Prioritize higher education contexts | Use examples and activities specific to university teaching. | |

| Missing concrete tools or examples | Incorporate current ready-to-use tools | Add practical sessions on Moodle use, authentic assessment, mentoring for master’s Theses, etc. | |

| Criticism of key modules | PSICO: obvious or poorly applicable content | Prioritize the redesign of these modules to make them more practical, relevant and better aligned with the needs of faculty | Redesign PSICO to include more applied content and sessions focused on real classroom situations and student management. |

| TUT: impractical approach and low utility | Refocus TUT on realistic tutorial scenarios. | ||

| TEC: outdated basic content; difficult to apply in a face-to-face setting | Update TEC contents and replace generic digital literacy topics with practical training on Moodle and UPM- specific tools. | ||

| EVA and INNOVA: missing concreteness and currently successful practices | Revise EVA and INNOVA to include current practices and successful case examples. | ||

| PLAN and MET: excessive load, dense and repetitive content | Make PLAN and MET more interactive and modular in structure. | ||

| PRACDO: need for more practical work and time dedication | Restructure the program to allocate more time to observing teaching practice. Implement guided microteaching sessions and include several feedback loops. | ||

| Main Problem 3: “Students Perceive the Workload and Task Design as Excessive, Unclear, and Difficult to Balance with Their Academic Responsibilities” | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Problems | General Solutions * | Specific Actions |

| Workload overload | Too many tasks | Limit number of tasks | Provide one integrated task per module and avoid duplication. Limit the number of assignments per module. Merge related tasks into a single comprehensive assignment whenever possible. |

| Excessive homework hours | Adjust estimated task time to align with ECTS credit guidelines | Estimate actual workload hours and adjust accordingly to match ECTS credits. | |

| Tasks accumulate across modules | Distribute tasks more evenly across the course timeline | Set assignment deadlines using a shared planning tool. | |

| Time management and compatibility | Hard to combine with work | Include in-class time for working on tasks | Reserve part of the in-person session to start or complete tasks. Integrate task completion time into in-person sessions when possible. |

| Rushed deadlines | Allow flexible deadlines whenever possible | Allow submission windows longer than one week. Offer flexible deadlines with extended submission periods. | |

| Group coordination issues | Offer individual alternatives to group assignments | Offer individual alternatives to group work for participants with scheduling conflicts. | |

| Task design and relevance | Too long tasks or redundant | Align tasks with essential teaching activities | Design tasks focused on practical activities such as lesson planning, rubric creation, and real case studies. |

| Misaligned with real teaching | Adapt tasks to different academic profiles | Include flexible options based on role. | |

| Too many short tasks | Prioritize integrated tasks that offer clear practical value | Replace small, unfocused tasks with a single comprehensive assignment that applies the course content in a practical context. | |

| Instructions and clarity | Unclear guidelines | Clarify and improve task instructions | Provide concise instructions for each task. Include grading rubrics and templates. Upload sample tasks to Moodle with estimated completion times. Offer clear examples to guide participants. |

| No time estimation | Add time estimate | Include estimated durations for each task. Require students to note the time they spend on each task. Balance and regulate workload based on students’ records. | |

| Misaligned objectives | Align each task with specific learning goals | Map each task explicitly to its corresponding module objective. Link every task directly to the module’s defined learning outcomes. | |

| Feedback and evaluation * | Late feedback | Establish deadline for returning feedback | Provide feedback within two weeks of submission. Set a maximum time of two weeks for all feedback. |

| Overlapping corrections | Feedback should be part of each module session | Allocate time in each module session to discuss tasks. Return oral and group feedback on assignments. Offer feedback opportunities during in-class sessions using instructor-led discussions or via peer review. | |

| Lack of guidance | Use guided rubrics | Use standardized rubrics across all modules to clarify the criteria for task assessment and provide formative feedback. Incorporate guided self-assessment and peer-review activities as part of the learning process. | |

| Coordination and course structure | Overlapping deadlines | Create shared calendars for all tasks | Publish a course-wide calendar with all deadlines Create and share a unified calendar of all course deadlines. Avoid overlapping submission dates between modules. |

| One task per session | Reduce frequency of required submissions | Limit tasks to one every 2–3 sessions if possible | |

| Moodle disorganized | Standardized task posting and deadlines on Moodle | Unify format and deadlines for all tasks in Moodle. Organize Moodle task areas consistently to reduce confusion. | |

| Main Problem 4: “Limited Opportunities for Meaningful Peer Collaboration” | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Category | Problems | General Solutions | Specific Actions |

| Few group activities | Most tasks are individual | Increase the number of group-based tasks | Design specific group assignments within core modules to foster peer collaboration. |

| Group work not encouraged across modules | Standardize the inclusion of group tasks | Include at least one collaborative activity across all modules. | |

| Final group work discouraged | Emphasize the value of teamwork in assessment criteria | Incorporate mixed assessment formats (individual and group) taking advantage of the added value of teamwork for developing teaching competences related to collaborative skills. | |

| Lack of networking tools | No platform for ongoing communication | Enable digital tools to support networking and peer interaction | Activate Moodle forums to encourage discussion among peers. Suggest professional networks such as LinkedIn for ongoing peer connection. |

| No group continuity after course | Facilitate alumni connections | Create an ICE alumni mailing list to keep contact and share information about university teaching events. Invite to webinars and meet-ups to support continued learning and networking. | |

| No digital community building | Use online platforms for community development | Launch Slack or Teams group to share teaching resources and program updates and events. | |

| Time constraints | Tight course schedule | Rebalance program schedule | Distribute collaborative tasks in a balanced and systematic way throughout the weeks to avoid clustering. |

| Heavy workload in class moments | Reduce individual workload | Replace one long individual task with a shorter group task. | |

| Difficult coordination | Use asynchronous collaboration | Enable collaborative documents and forum debates to allow flexibility between participants. | |

| Missed pedagogical opportunities | No peer teaching activities | Include peer instruction | Assign microteaching activities where participants teach their peers. |

| Little role-playing or simulation | Use experiential learning techniques | Add role-play activities across module sessions. | |

| Peer feedback underused | Include structured peer review | Use peer-evaluation rubrics in PRACDO and MET module tasks | |

| Limited interaction spaces | Lack of collaboration in-class moments | Incorporate group tasks * | Introduce debate techniques, case study or any methodology which means exchanging views * |

| No structured moments for peer exchange | |||

| Lack of materials for collaborative tasks | Provide resources for teamwork | Offer templates, post-its, shared documents, or digital whiteboards | |

Appendix E

- Original Cause–Effect Diagrams Generated by ChatGPT

References

- Benavides, C., & López, N. (2020). Retos contemporáneos para la formación permanente del profesorado universitario. Educación y Educadores, 23(1), 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borakati, A. (2021). Evaluation of an international medical E-learning course with natural language processing and machine learning. BMC Medical Education, 21(1), 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buils, S., Viñoles-Cosentino, V., Esteve-Mon, F. M., & Sánchez-Tarazaga, L. (2024). La formación digital en los programas de iniciación a la docencia universitaria en España: Un análisis comparativo a partir del DigComp y DigCompEdu. Educación XX1, 27(2), 37–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgasí Delgado, D. D., Cobo Panchi, D. V., Pérez Salazar, K. T., Pilacuan Pinos, R. L., & Rocha Guano, M. B. (2021). El diagrama de Ishikawa como herramienta de calidad en la educación: Una revisión de los últimos 7 años. Revista Electrónica Tambara, 14(84), 1212–1230. [Google Scholar]

- Chaves, A. A., & Saborío-Taylor, S. (2025). Integración de la inteligencia artificial en los procesos de investigación educativa y evaluación de aprendizajes: Una experiencia con estudiantes de la carrera de Estudios Sociales y Educación Cívica en la Universidad Nacional de Costa Rica. Revista de Investigación e Innovación Educativa, 3(1), 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristi-González, R., Mella-Huenul, Y., Fuentealba-Ortiz, C., Soto-Salcedo, A., & García-Hormazábal, R. (2023). Competencias docentes para el aprendizaje profundo en estudiantes universitarios: Una revisión sistemática. Revista de Estudios y Experiencias en Educación, 22(50), 28–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Cruz, M. Á. (2000). Formación pedagógica inicial y permanente del profesor universitario en España: Reflexiones y propuestas. Revista Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 37(1), 95–114. [Google Scholar]

- Dengel, A., Gehrlein, R., Fernes, D., Görlich, S., Maurer, J., Pham, H. H., Großmann, G., & Dietrich genannt Eisermann, N. (2023). Qualitative research methods for large language models: Conducting semi-structured interviews with ChatGPT and BARD on computer science education. Informatics, 10(4), 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiSabito, D., Hansen, L., Mennella, T., & Rodriguez, J. (2025). Exploring the frontiers of generative AI in assessment: Is there potential for a human–AI partnership? New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 182, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Oria, M. (2023). Can AI language models improve human sciences research? A phenomenological analysis and future directions. Encyclopaideia, 27(66), 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice. (2020). The European higher education area in 2020: Bologna process implementation report. Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feixas, M., Lagos, P., Fernández, I., & Sabaté, S. (2015). Modelos y tendencias en la investigación sobre efectividad, impacto y transferencia de la formación docente en educación superior. Educar, 51(1), 81–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, A. (2008). La formación inicial del profesorado universitario: El título de Especialista Universitario en Pedagogía Universitaria de la Universidad Politécnica de Valencia. Revista Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 22(3), 161–187. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, M., & Intriago, L. (2025). Diseño de un plan de autoevaluación para mejorar la calidad educativa en la Educación Superior. Revista Científica Arbitrada Multidisciplinaria Pentaciencias, 7(1), 223–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, G. Y., García, R. I., & Lozano, A. (2020). Calidad en la educación superior en línea: Un análisis teórico. Educación, 44(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, G., & Coffey, M. (2004). The impact of training of university teachers on their teaching skills, their approach to teaching and the approach to learning of their students. Active Learning in Higher Education, 5(1), 87–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobierno de España. (2023, May 23). Ley orgánica 2/2023, de 22 de marzo, del Sistema Universitario. Boletín Oficial del Estado, núm. 70. Available online: https://www.boe.es/eli/es/lo/2023/03/22/2/con (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Goyanes, M., & Lopezosa, C. (2024). ChatGPT en Ciencias Sociales: Revisión de la literatura sobre el uso de inteligencia artificial (IA) de OpenAI en investigación cualitativa y cuantitativa. Anuario ThinkEPI, 18, e18e04. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guijarro, A. D. L. Á. (2024). Impacto de la inteligencia artificial en la evaluación y retroalimentación educativa. Revista Retos para la Investigación, 3(1), 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, L., Elliott, D., Quick, A., Smith, S., & Choplin, V. (2023). Exploring the use of AI in qualitative analysis: A comparative study of guaranteed income data. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 22, 16094069231201504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haras, C. (2018, January 17). Faculty development as authentic professional practice. Higher Ed Today. Available online: https://www.higheredtoday.org/2018/01/17/faculty-development-authentic-professional-practice/ (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Hinojo, F. J., Aznar, I., Rodríguez, A. M., & Romero, J. M. (2020). La carrera docente universitaria en España: Perspectiva profesional de los contratados predoctorales FPU y FPI. Revista Electrónica Interuniversitaria de Formación del Profesorado, 23(3), 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Hunkoog, J., & Minsu, H. (2024). Towards effective argumentation: Design and implementation of a generative AI-based evaluation and feedback system. Journal of Baltic Science Education, 23(2), 280–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Instituto de Ciencias de la Educación–UPM. (2025). Programa superior de formación para la docencia universitaria (15 ECTS). Available online: https://ice.upm.es/formacion/docencia-universitaria (accessed on 7 August 2025).

- Kabir, A., Shah, S., Haddad, A., & Raper, D. M. S. (2025). Introducing our custom GPT: An example of the potential impact of personalized GPT builders on scientific writing. World Neurosurgery, 193, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klyshbekova, M., & Abbott, P. (2024). ChatGPT and assessment in higher education: A magic wand or a disruptor? Electronic Journal of e-Learning, 22(2), 30–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koltai, J., Kmetty, Z., & Bozsonyi, K. (2021). From Durkheim to machine learning: Finding the relevant sociological content in depression and suicide-related social media discourses. In B. D. Loader, M. Stephenson, & J. Busher (Eds.), Pathways between social science and computational social science: Theories, methods, and interpretations (pp. 237–258). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z., Zhang, W., Sun, J., Cheng, H. N. H., Peng, X., & Liu, S. (2016, September 22–24). Emotion and associated topic detection for course comments in a MOOC platform. 2016 International Conference on Educational Innovation through Technology (EITT) (pp. 15–20), Tainan, Taiwan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Losada, L., & Moreno, Ó. (2024). Evaluación de programas diseñados bajo el enfoque de competencias. Validación de un instrumento. In Congreso internacional ideice, volume (Vol. 14, pp. 389–395). Congreso Internacional Ideice. [Google Scholar]

- Malagón, F. J., Cadilla, M., Sánchez-Sánchez, A. M., & Graell, M. (2025). Literatura científica sobre la formación del profesorado universitario en España: Análisis temático. European Public & Social Innovation Review, 10, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín, J. L., Pablo-Lerchundi, I., Núñez-del-Río, M. C., Del-Mazo-Fernández, J. C., & Bravo-Ramos, J. L. (2018). Impact of the initial training of engineering schools’ lecturers. International Journal of Engineering Education, 34(5), 1440–1450. [Google Scholar]

- Montes, D. A., & Suárez, C. I. (2016). La formación docente universitaria: Claves formativas de universidades españolas. Revista Electrónica de Investigación Educativa, 18(3), 51–64. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, D. L. (2023). Exploring the use of artificial intelligence for qualitative data analysis: The case of ChatGPT. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 22, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moustakas, C. (1994). Phenomenological research methods. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Natukunda, A., & Muchene, L. K. (2023). Unsupervised title and abstract screening for systematic review: A retrospective case-study using topic modelling methodology. Systematic Reviews, 12(1), 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ochoa Oliva, M. (2022). Aseguramiento y reconocimiento de la calidad en la Educación Superior a través de las nuevas formas de medición: Desafíos, oportunidades y mejores prácticas. Tecnología Educativa. Revista CONAIC, 8(3), 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogundoyin, S. O., Ikram, M., Asghar, H. J., Zhao, B. Z. H., & Kaafar, D. (2025). A large-scale empirical analysis of custom GPTs’ vulnerabilities in the OpenAI ecosystem. arXiv, arXiv:2505.08148. [Google Scholar]

- OpenAI. (2025a). GPT-4o and more tools to ChatGPT free. OpenAI. Available online: https://openai.com/index/gpt-4o-and-more-tools-to-chatgpt-free/ (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- OpenAI. (2025b). ChatGPT (o4-mini) [Large language model]. Available online: https://chat.openai.com/ (accessed on 5 August 2025).

- OpenAI. (n.d.) CHATGPT general FAQ. OpenAI help center. Available online: https://help.openai.com/en/articles/6783457-chatgpt-general-faq (accessed on 16 February 2023).

- Oshanova, A., Sargeant, J., Karim, M., & Yates, M. (2025). Assessing the efficacy of an artificial intelligence–driven essay feedback tool in undergraduate education: A randomized controlled trial. Computers & Education, 216, 104870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paricio, J., Fernández, A., & Fernández, I. (2019). Cartografía de la buena docencia universitaria: Un marco para el desarrollo del profesorado basado en la investigación (Vol. 52). Narcea Ediciones. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, R. D., Mancini, K., & Abram, M. D. (2023). Natural language processing enhanced qualitative methods: An opportunity to improve health outcomes. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 22, 280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, R., & Ruiz, C. (2020). Evaluación de impacto de los programas formativos: Aspectos fundamentales, modelos y perspectivas actuales. Revista Educación, 44(2), 541–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Rodríguez, N. (2019). Programas de formación docente en educación superior en el contexto español. Investigación en la Escuela, 97, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porlán, R., Martín-Lope, M., Villarejo, Á. F., Moncada, B., Obispo, B., Morón, C., Aguilar, D., Campos, M., & Rubio, M. R. (2024a). Recomendaciones estratégicas para la formación docente de ayudantes doctores: Hacia un modelo docente centrado en el aprendizaje activo del estudiante. Red Colaborativa Interuniversitaria de Formación, Innovación e Investigación Docente. Available online: https://institucional.us.es/fidopus/ (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Porlán, R., Pérez-Robles, A., & Delord, G. (2024b). La didáctica de las ciencias y la formación docente del profesorado universitario. Enseñanza de las Ciencias, 42(1), 5–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QS Top Universities. (2025). University subject rankings: Engineering and technology. Available online: https://www.topuniversities.com/university-subject-rankings/engineering-technology (accessed on 8 August 2025).

- Reyes-Zúñiga, C. G., Sandoval-Acosta, J. A., & Osuna-Armenta, M. O. (2024). Integración de IA en la retroalimentación académica: Un análisis exploratorio en ingeniería en sistemas computacionales. Revista Interdisciplinaria de Ingeniería Sustentable y Desarrollo Social, 10(1), 330–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosalind, J., & Suguna, S. (2022). Predicting students’ satisfaction towards online courses using aspect-based sentiment analysis. In E. J. Neuhold, X. Fernando, J. Lu, S. Piramuthu, & A. Chandrabose (Eds.), Computer, communication, and signal processing: ICCCSP 2022 (Vol. 651, pp. 27–39). IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rué, J., Arana, A., González de Audícana, M., Abadía Valle, A. R., Blanco Lorente, F., Bueno García, C., & Fernández March, A. (2013). Teaching development in higher education in Spain: The optimism of the will within a black box model. Revista de Docencia Universitaria, 11(3), 125–158. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Cabezas, A., Medina-Domínguez, M. C., Subía-Álava, A. B., & Delgado-Salazar, J. L. (2022). Evaluación de un programa de formación de profesores universitarios en competencias: Un estudio de caso. Formación Universitaria, 15(2), 41–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltos-García, P. A., Zambrano-Loja, C. M., Rodríguez-Carló, D. F., & Cobeña-Talledo, R. A. (2024). Análisis del impacto de las estrategias de seguimiento académico basados en la inteligencia artificial en el rendimiento de estudiantes universitarios en programas de administración. MQRInvestigar, 8(2), 1930–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez Núñez, J. A. (2007). Formación inicial para la docencia universitaria. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación, 42(5), 1–17. Available online: https://rieoei.org/historico/deloslectores/sanchez.PDF (accessed on 1 February 2025).

- Sbalchiero, S., & Eder, M. (2020). Topic modeling, long texts and the best number of topics: Some problems and solutions. Quality & Quantity, 54(4), 1095–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaik, T., Tao, X., Li, Y., Dann, C., McDonald, J., Redmond, P., & Galligan, L. (2022). A review of the trends and challenges in adopting natural language processing methods for education feedback analysis. IEEE Access, 10, 56720–56737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejada, J., & Ferrández, E. (2012). El impacto de la formación continua: Claves y problemáticas. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación, 58(3), 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tello Díaz-Maroto, I. (2010). Modelo de evaluación de la calidad de cursos formativos impartidos a través de Internet. RIED. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación a Distancia, 13(1), 209–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiana, A. (2013). Tiempos de cambio en la universidad: La formación pedagógica del profesorado universitario en cuestión. Revista de Educación, 362, 12–38. [Google Scholar]

| Question | Response Options |

|---|---|

| (8) What aspects of the course did you like the most, and why? * | Free text |

| (9) What aspects of the course did you like the least, and why? * | Free text |

| (10) What suggestions do you have to improve this program? * | Free text |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Míguez-Souto, A.; Gutiérrez García, M.Á.; Martín-Núñez, J.L. Exploring the Use of AI to Optimize the Evaluation of a Faculty Training Program. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1394. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101394

Míguez-Souto A, Gutiérrez García MÁ, Martín-Núñez JL. Exploring the Use of AI to Optimize the Evaluation of a Faculty Training Program. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1394. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101394

Chicago/Turabian StyleMíguez-Souto, Alexandra, María Ángeles Gutiérrez García, and José Luis Martín-Núñez. 2025. "Exploring the Use of AI to Optimize the Evaluation of a Faculty Training Program" Education Sciences 15, no. 10: 1394. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101394

APA StyleMíguez-Souto, A., Gutiérrez García, M. Á., & Martín-Núñez, J. L. (2025). Exploring the Use of AI to Optimize the Evaluation of a Faculty Training Program. Education Sciences, 15(10), 1394. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101394