“I Am for Diversity…”: How a Victimhood Legal Formula Weaponizes Faculty Academic Freedom Against Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Social Justice

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Weaponizing Academic Freedom and Freedom of Speech to Mischaracterize DEI

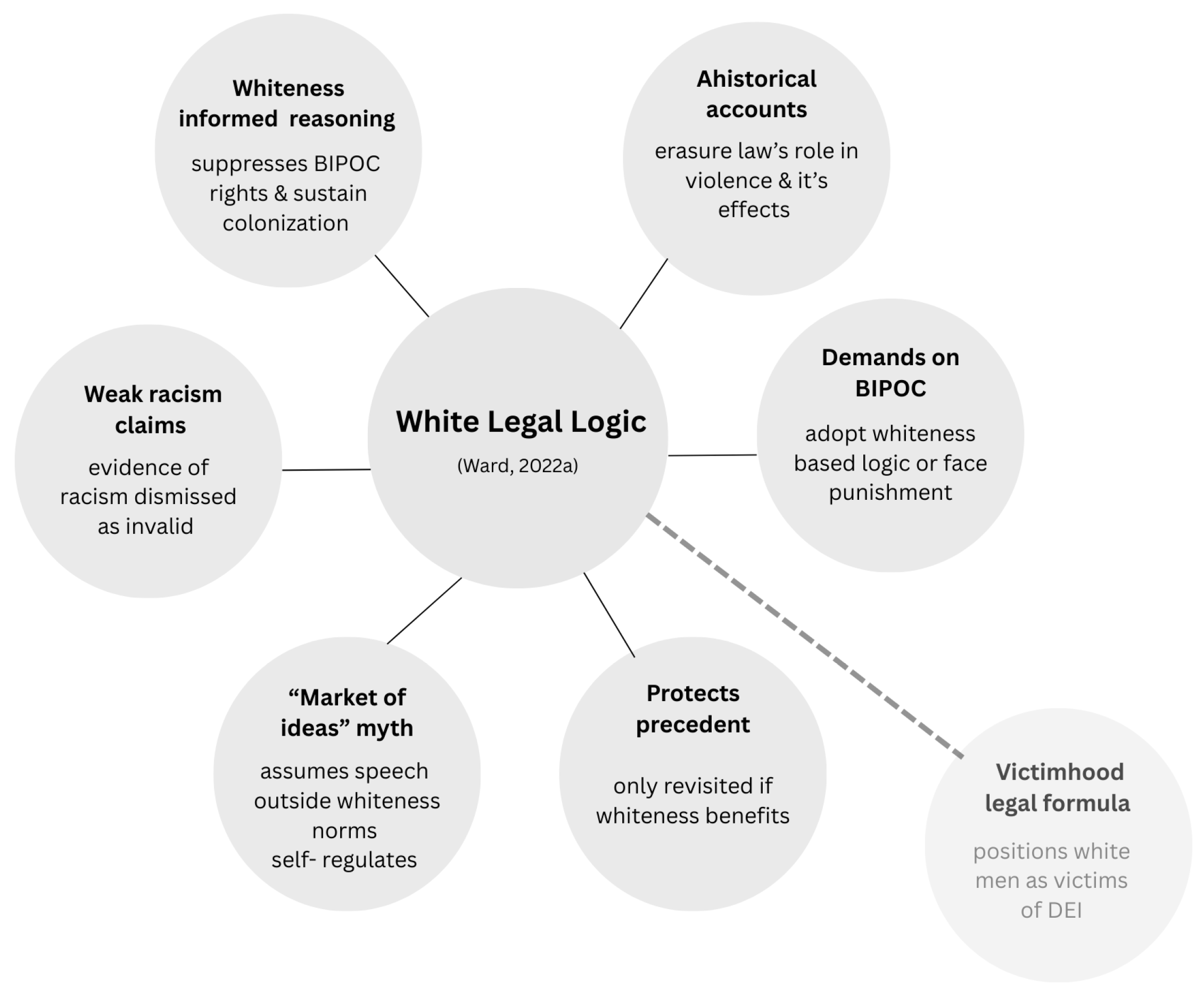

1.2. Theoretical Framework

2. Methodology

2.1. Researchers’ Positionality

2.2. Methods

“1. Identify relevant social identities and explore how power dynamics (historical and contemporary), legal discourse(s), and hegemonic processes obfuscate or normalize subordination and discrimination. 2. Identify legal framing that sets up the boundaries of laws (i.e., what is included and excluded), “relevant facts” that align with current laws, law’s application to the relevant facts, and resulting legal decisions. 3. Analyze discursive tactics employed in a court’s explanation and justification of frames, name rhetorical practices, and clarify ideologies that go into making up the law’s articulations. 4. Critique how legal framing and discourse of court (s) relate to and connect with the racialized practices, institutional arrangements, and structures that maintain white supremacy, genderism, heteronormativity, and other systems of subordination”.

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Findings

2.5.1. Plaintiffs Constructed a Dual Legal Narrative, Positioning Themselves as Victims and Champions of DEI Initiatives by Simultaneously Mischaracterizing DEI to Align with Their Own Ideological Perspectives

[T]his mode of thinking teaches people to see the worst in other people, promotes a culture of victimhood, and suppresses alternative viewpoints instead of encouraging growth and dialogue… [As] many of the statements that the flier condemns as “microaggressions” can (and should) be interpreted in a benign or positive manner. However, the fliers teach people to focus on the worst possible interpretation of the statement, to disregard the speaker’s intent, and to impute a discriminatory motive to others.

2.5.2. Plaintiffs Weaponized Academic Freedom and Free Speech Legal Precedents to Frame Their Purported Ideological Dissent About DEI Initiatives as a Constitutionally Protected Right

The cornerstone of higher education is the ability of professors to participate freely in the “marketplace of ideas,” where all viewpoints can be debated on their merits… Seeking to participate in this marketplace, Plaintiff Nathaniel Hiers obtained his doctorate in Mathematics.

the teaching of critical race theory to young children… [is] a grave misuse of state fund for public purposes…UT’s use of DEI grants… [is] the diversion of state resources to political advocacy through bureaucratic means and the lack of oversight by elected officials.

3. Discussion

4. Implications

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DEI | Diversity, equity, inclusion |

| BIPOC | Black, Indigenous, and more racially minoritized People of Color |

| AAUP | American Association of University Professors |

| SCOTUS | Supreme Court of the United States |

| IDA | Intersectionality Discourse Analysis |

| CRT | Critical Race Theory |

| CED | College of Education |

| UT | The University of Texas at Austin |

| 1 | We choose to use the color-evasive and gender-evasive in lieu of Carbado’s (2013) two concepts: “color-blind intersectionality” and “gender-blind intersectionality” in our commitment to rethinking and removing ableist language in all aspects of our work, particularly in research and scholarship (Annamma et al., 2013). Carbado (2013) defines color-evasive intersectionality as “instances in which whiteness helps to produce and is part of a cognizable social category but is invisible or unarticulated as an intersectional subjected position” (p. 817) and gender-evasive intersectionality in a “similar intersectional elision with respect to gender” (p. 817). |

| 2 | There appears to be a discrepancy within the Hiers v. The Bd. of Regents of the Univ. of N. Tex. Sys. (2020 complaint. On page 2 paragraph 5, the plaintiff states they wrote, “Don’t leave the garbage lying around.” However, on page 13 paragraph 112, the complaint references the statement as, “Please don’t leave garbage lying around.” |

References

- AAUP. (n.d.). Shared governance. American Association of University Professors. Available online: https://www.aaup.org/our-programs/shared-governance (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Abrams v. United States, 250 U.S. 616. (1919). Available online: https://www.oyez.org/cases/1900-1940/250us616 (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Adam Sachs, J., & Young, J. C. (2025, January 2). For federal censorship of higher education, here’s what could happen in 2025. PEN America. Available online: https://pen.org/for-federal-censorship-of-higher-ed-heres-what-could-happen-in-2025/ (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Altbach, P., Berdahl, R., & Gumport, P. (Eds.). (1999). American higher education in the twenty-first century: Social, political, and economic challenges. Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Annamma, S. A., Connor, D., & Ferri, B. (2013). Dis/ability critical race studies (DisCrit): Theorizing at intersections or race and dis/ability. Race, Ethnicity, and Education, 16(1), 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benitez, L., Reid, A., & Friedman, J. (2025, July 24). With a wave of new bills in 2025, states legislators cast a web of control over higher education. PEN America. Available online: https://pen.org/with-a-wave-of-new-bills-in-2025-state-legislators-cast-a-web-of-control-over-higher-education/ (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Braley-Rattai, A., & Bezanson, K. (2020). Uncharted waters: Ontario’s campus speech directive and the intersections of academic freedom, expressive freedom, and institutional autonomy. Constitutional Forum, 29(2), 65–78. [Google Scholar]

- Briscoe, K., Jones, V. A., & Guess, A. (2025). Contextualizing the discourses in anti-CRT legislation through faculty counterstories. Innovation Higher Education, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briscoe, K., Jones, V. A., & Whitehead, M. A. (2024). “Behind the veil”: Unmasking anti-blackness in presidential discourse and responses to racialized incidents. The Review of Higher Education, 49(1), 33–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabrera, N. L. (2024). Whiteness in the ivory tower: Why don’t we notice the white students sitting together in the quad? Teachers College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carbado, D. W. (2013). Colorblind intersectionality. Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 38(4), 811–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemerinsky, E. (1998). Is tenure necessary to protect academic freedom? American Behavioral Scientist, 41, 638–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemerinsky, E. (2023). Education, the first amendment, and the constitution. University of Cincinnati Law Review, 92(1), 12–30. [Google Scholar]

- Connick v. Myers, 461 U.S. 138. (1983). Available online: https://www.oyez.org/cases/1982/81-1251 (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Crenshaw, K. (2023). The panic over critical race theory is an attempt to whitewash U.S. history. In E. Taylor, D. Gillborn, & G. Ladson-Billings (Eds.), Foundations of critical race theory in education (pp. 362–364). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado Bernal, D., & Villalpando, O. (2002). An apartheid of knowledge in academia: The struggle over “legitimate” knowledge of faculty of Color. Equity & Excellence in Education, 35(2), 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embrick, D. G., & Moore, W. L. (2020). White space(s) and the reproduction of white supremacy. American Behavioral Scientist, 64(14), 1935–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Executive Order No. 14151, 3 C.F.R. 1. (2025). Available online: https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/ending-radical-and-wasteful-government-dei-programs-and-preferencing/ (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Executive Order No. 14173, 3 C.F.R. 1. (2025). Available online: https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/ending-illegal-discrimination-and-restoring-merit-based-opportunity/ (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Friedman, J., LaFrance, S., & Meehan, K. (2023, August 23). Educational intimidation: How “parents’ rights” legislation undermines the freedom to learn. PEN America. Available online: https://pen.org/report/educational-intimidation/ (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Garcetti v. Ceballos, 547 U.S. 410. (2006). Available online: https://www.oyez.org/cases/2005/04-473 (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Gillborn, D. (2007). Education policy as an act of white supremacy: Whiteness, critical race theory, and education reform. Journal of Education Policy, 20(4), 485–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givhan v. W. Line Consol. Sch. Dist., 439 U.S. 410. (1979). Available online: https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/439/410/ (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Gusa, D. (2010). White institutional presence: The impact of whiteness on campus climate. Harvard Educational Review, 80(4), 464–490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, S. (2012). Race without racism: How higher education researchers minimize racist institutional norms. Review of Higher Education, 36(1), 9–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harper, S., Chang, M. J., Cole, E. R., Patton Davis, L., Gayles, J. G., Jenkins, T. S., Kimbrough, W. M., Park, J. J., Saenz, V. B., Smith, S. M., & Wolf-Wendel, L. (n.d.). Truths about DEI on college campuses: Evidence- based expert responses to politicized misinformation. USC Race and Equity Center. Available online: https://race.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Harper-and-Associates-DEI-Truths-Report.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Harris, A. P. (2019). Racing Law: Legal scholarship and the critical race revolution. Equity & Excellence in Education, 51(1), 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazel, M. (2025). The madness behind the method: What’s really beneath anti-critical race theory legislation. Education Policy, 39(7), 1357–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiers v. The Bd. of Regents of the Univ. of N. Tex. Sys. (2020). Available online: https://casetext.com/case/hiers-v-the-bd-of-regents-of-the-univ-of-n-tex-sys (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Innis, L. B. (2010). A critical legal rhetoric approach to in re African-American slave descendants litigation. Journal of Civil Rights and Economic Development, 24(4), 649–696. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplin, W. A., & Lee, B. A. (2014). The law of higher education (5th ed.). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Keyishian v. Board of Regents, 385 U.S. 589. (1967). Available online: https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/385/589/ (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Ladson-Billings, G. (2000). Racialized discourses and ethnic epistemologies. In N. Denzin, & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (2nd ed., pp. 257–277). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, C. R. (1990). If he hollers let him go: Regulating racist speech on campus. Duke Law Journal, 1990(3), 431–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowery v. Mills. (2023). Available online: https://casetext.com/case/lowery-v-mills-9 (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Moore, W. L. (2014a). The stare decisis of racial inequality: Supreme Court race jurisprudence and the legacy of legal apartheid in the United States. Critical Sociology, 40(1), 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, W. L. (2014b). White lies: Social science research, judicial decision-making, and the fallacy of objectivity. In B. L. Bartels, & C. W. Bonneau (Eds.), Making law and courts research relevant (pp. 79–96). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, W. L. (2020). The mechanisms of white space(s). American Behavior Scientist, 64(14), 1946–1960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñiz, R. (2024). Exploring litigation of anti-crt action: Considering the issues, challenges, & risks in a time of white backlash. Syracuse Law Review, 74(1071), 1071–1110. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Education Statistics. (2024). Fast facts: Race/ethnicity of college faculty. Available online: https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=61 (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Patton, L. D. (2016). Disrupting postsecondary prose: Toward a critical race theory of higher education. Urban Education, 51(3), 315–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedota, J., Garces, L. M., Bentley Epstein, E. M., Cruz, Ngaosi, N., & Khalayleh, N. (2025). “We’re on our own our here”: Faculty member responses to legislative threats to academic freedom and scholarship on race. The Journal of Higher Education, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PEN America. (n.d.). PEN America index of educational gag order laws. Available online: https://pen.org/educational-censorship/index-of-educational-gag-orders/ (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Pickering v. Board of Education, 391 U.S. 563. (1968). Available online: https://www.oyez.org/cases/1967/510 (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Poch, R. K. (1993). Academic freedom in American higher education: Rights, responsibilities and limitations. ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Report No. 4. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED366263.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Porter v. Board of Trustees of N. C. State University. (2022). Available online: https://stephenporter.org/wokejoke/complaint.pdf (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Ray, V. (2019). A theory of racialized organizations. American Sociological Review, 84(1), 26–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenck v. United States, 249. U.S. 47. (1919). Available online: https://www.oyez.org/cases/1900-1940/249us47 (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Slaughter, S., & Rhoades, G. (2004). Academic capitalism and the new economy. Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stefancic, J., & Delgado, R. (2018). Must we defend nazis? Why the first amendment should not protect hate speech and white supremacy. NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- Strasser, M. (2018). Pickering, garcetti, & academic freedom. Brooklyn Law Review, 83(2), 579–612. [Google Scholar]

- Ward, L. W. M. (2022a). A critical race theory perspective on assaultive speech in U.S. campus communities. Equity & Excellence in Education, 55(3), 244–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, L. W. M. (2022b). Weaponizing free speech protections in US higher education: The ugly impact of assaultive speech on Black women students. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 2022, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waters v. Churchill, 511 U.S. 661. (1994). Available online: https://www.oyez.org/cases/1993/92-1450 (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Whitney v. California, 274 U.S. 357. (1927). Available online: https://www.oyez.org/cases/1900-1940/274us357 (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Williamson-Lott, J. A. (2018). Jim Crow campus: Higher education and the struggle for new social order. Teacher College Press. [Google Scholar]

- Zuberi, T., & Bonilla-Silva, E. (Eds.). (2008). White logic, white methods: Racism and methodology. Rowman & Littlefield. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ward, L.W.; Rodriguez, D. “I Am for Diversity…”: How a Victimhood Legal Formula Weaponizes Faculty Academic Freedom Against Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Social Justice. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1364. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101364

Ward LW, Rodriguez D. “I Am for Diversity…”: How a Victimhood Legal Formula Weaponizes Faculty Academic Freedom Against Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Social Justice. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1364. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101364

Chicago/Turabian StyleWard, LaWanda Wynette, and Daisy Rodriguez. 2025. "“I Am for Diversity…”: How a Victimhood Legal Formula Weaponizes Faculty Academic Freedom Against Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Social Justice" Education Sciences 15, no. 10: 1364. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101364

APA StyleWard, L. W., & Rodriguez, D. (2025). “I Am for Diversity…”: How a Victimhood Legal Formula Weaponizes Faculty Academic Freedom Against Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Social Justice. Education Sciences, 15(10), 1364. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101364