1. Introduction

Schools have traditionally held a central role in the transmission of knowledge and the provision of education. However, recent social and technological developments are challenging this position. Digitalisation and artificial intelligence, together with alternative educational institutions and media, increasingly shape the landscape of learning (

Walter, 2024). Education, however, remains valuable for contemporary society, which was already described decades ago as a “knowledge society” or “education society” (

Bell, 1973;

Blau & Duncan, 1967;

Boudon, 1973;

Bowles & Gintis, 1976;

Lane, 1966). At the same time, critical voices have highlighted the risks of commercialisation and market orientation of the educational sector. (

Liessmann, 2009;

Lohmann & Rilling, 2002). In this context, schools’ social and cultural roles remain indispensable, as they represent spaces where values are shared across social differences and where education may contribute to bridging social inequalities.

Since 2004, the Czech Republic has been a member of the European Union (hereinafter “EU”). According to the earlier classification into common and community policies, education does not belong to the common policies within the EU, similar to the broader field of social policy. The EU only has supporting competences in this area (

European Commission, 2024). In practice, this implies that education policies fall exclusively within the competence of member states, while the EU’s role is limited to supporting national initiatives and coordinating selected activities. In the Czech Republic, these competences fall under the Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports (hereinafter “MEYS”).

Among the main international documents addressing educational policy, the Europe 2020 strategy, adopted by the European Council in 2010, holds particular significance. The strategy articulates three fundamental priorities, one of which specifically targets education (

Government of the Czech Republic, 2022). Regarding vocational training, the EU established a forum based on the preceding Lisbon Strategy. This platform, formally designated as Education and Training 2020, facilitates the systematic exchange of best practices, methods, and experience in the field of education.

European cooperation in the field of education and vocational training is implemented through the Copenhagen process (

MEYS, 2024b). Lifelong learning represents an integral part of contemporary education and employment policies. Following the negotiations held during the Lisbon European Council in 2000, the European Commission subsequently adopted the Memorandum on Lifelong Learning.

In the Czech Republic, the main document related to education is the Education Policy Strategy 2030+ (hereinafter “Strategy 2030+”). This document articulates two principal objectives: the transformation of educational content and the reduction in educational inequalities. These goals are operationalised through four strategic lines: (1) the comprehensive transformation of educational processes, (2) the mitigation of educational disparities, (3) the enhancement of teaching staff support and professional development, and (4) the establishment of sustainable financing mechanisms (

MEYS, 2024d).

The implementation of Strategy 2030+ is facilitated through the Long-Term Plan of the Education System of the Czech Republic 2023–2027 (hereinafter “the Long-Term Plan”). This document delineates three priorities: (1) personal development and motivation for lifelong learning, (2) modern education and prepared pedagogues, and (3) a sustainable and effective system based on responsibility for educational results (

MEYS, 2024a). The primary foundation for lifelong learning is established by the Lifelong Learning Strategy of the Czech Republic, adopted by the Government of the Czech Republic through Resolution No. 761 of 11 July 2007 (

MEYS, 2024c).

On the basis of another legal document, the decree on Further Education of Pedagogical Staff, a career regulation (system) was to be introduced from 2014 (

MEYS, 2024e). However, it was rejected by the Chamber of Deputies of the Parliament of the Czech Republic in July 2017 and is currently being revised. Beyond these legislative impediments, the professional development of teaching staff confronts numerous systemic challenges characteristic of combining study with employment. According to data from the Czech Statistical Office (hereinafter “CZSO”), these barriers encompass temporal and financial constraints, insufficient institutional support from employers, and the demanding nature of concurrent study requirements while maintaining professional responsibilities (

CZSO, 2013).

Despite increasing recognition of the role of teacher professional development, several gaps persist in the current literature. As

Richter et al. (

2025) point out, most studies measure teachers’ motivation without a specific focus on their specialisation. Much of the existing literature focuses on technical training aspects, with limited examination of how professional development influences teachers’ attitudes and motivation (

Amemasor et al., 2025). Methodologically, only a limited number of studies employ rigorous experimental designs (

Ventista & Brown, 2023), while the current literature overlooks context-specific evaluations for socio-economic conditions (

Liu & Li, 2025). Recent studies emphasise barriers, including inadequate institutional support and heavy workloads (

Eroglu & Donmus Kaya, 2021), yet comprehensive longitudinal analyses examining employer support-motivation relationships remain scarce. As

Rodríguez-Rivero et al. (

2023) note, professional well-being and motivation are influenced by factors such as personal values, available time, and institutional context. This perspective situates our study within the broader international discourse on teacher motivation and lifelong learning.

This study addresses these gaps by examining the intersection of labour market position, study motivation, and perceived barriers among Czech secondary school teachers through a mixed-method approach. The research offers a comprehensive analysis of employer-driven versus self-motivated professional development participation within the specific context of Czech educational policy frameworks, contributing both theoretical insights into motivation-barrier relationships and practical recommendations for policy enhancement.

2. Materials and Methods

The first research technique employed is document analysis. The method was applied to three key documents. The primary document analysed was “Education at a Glance,” which presents annual survey results conducted by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (hereinafter “OECD”) and enables a comparison of education systems in OECD countries through selected indicators. The second document examined was Education and training in the EU—facts and figures, in which Eurostat presents findings from its annual survey on education across EU member states. The final document utilised is the publication Teaching and Learning International Survey 2018 Results (hereinafter “TALIS 2018”), which is available on the website of the Czech School Inspectorate (hereinafter “CSI”).

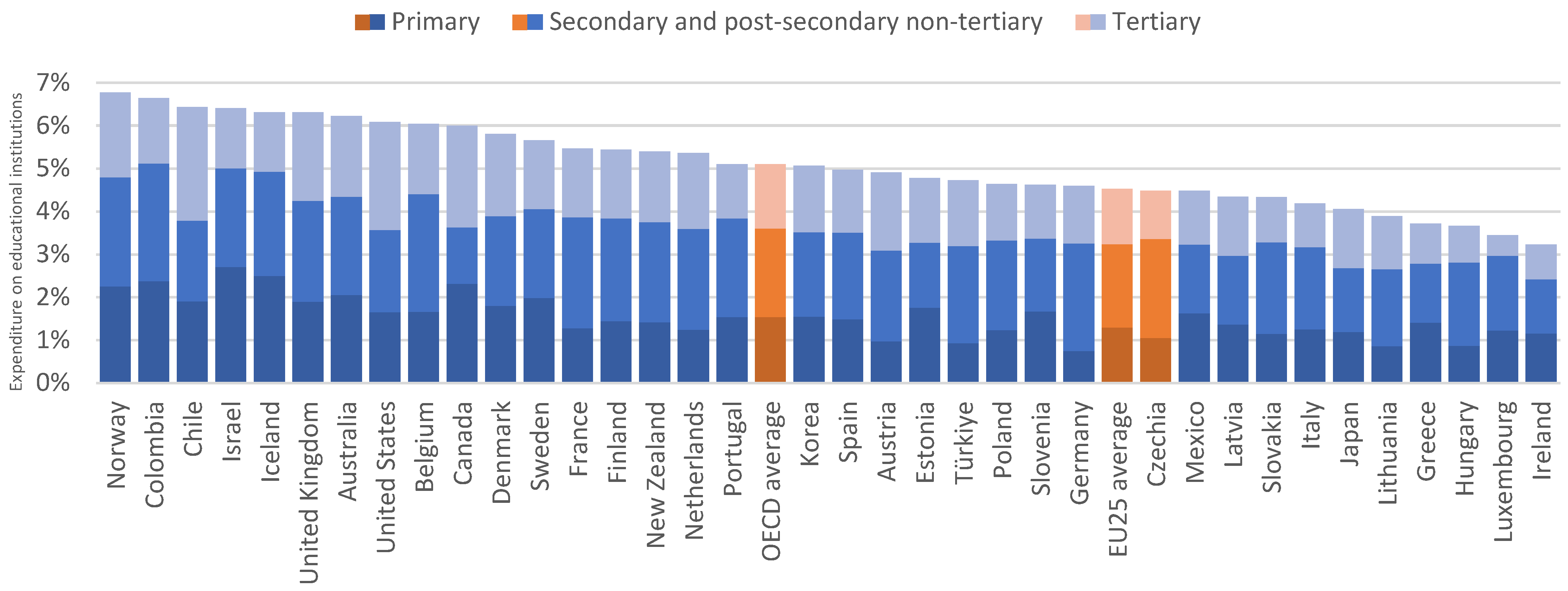

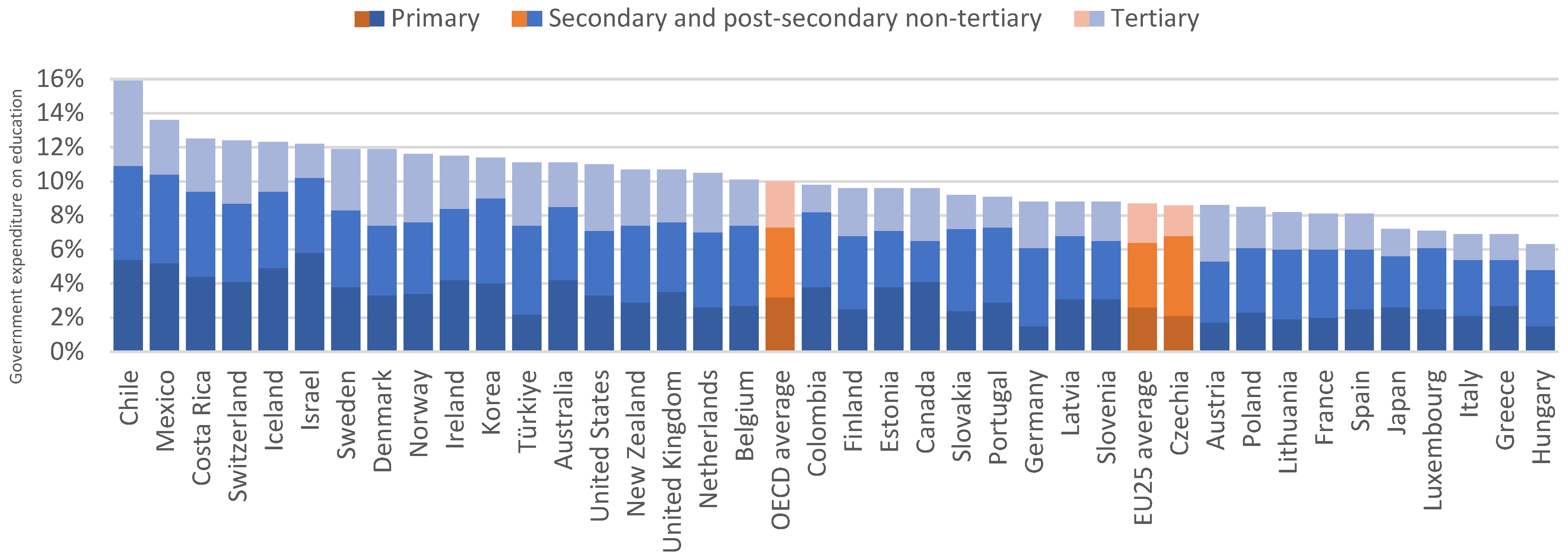

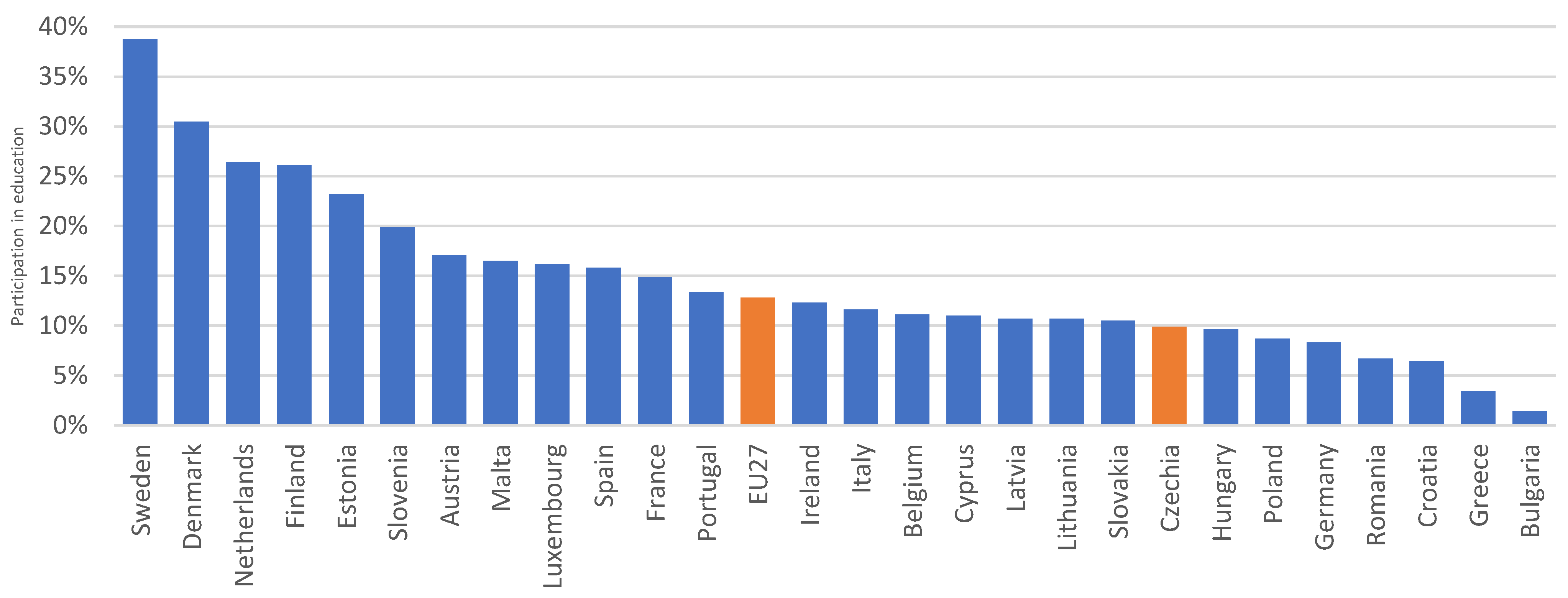

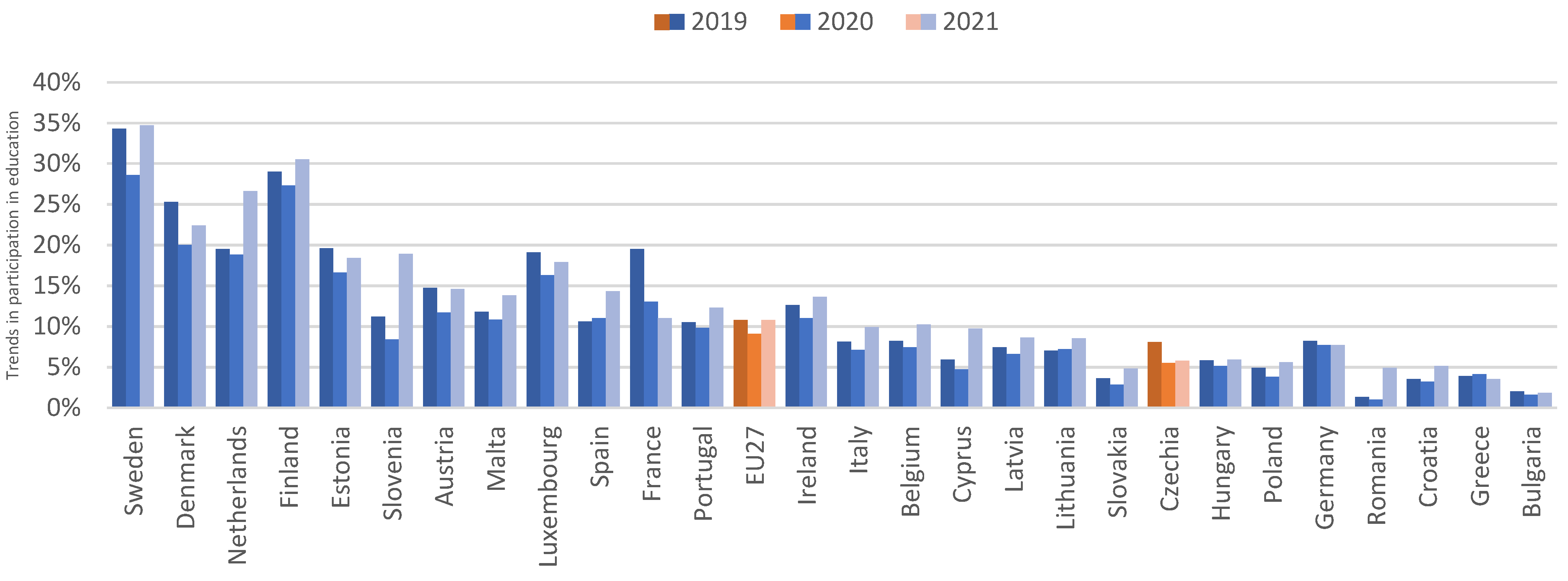

The analysis employs eight criteria to assess educational priorities and the attractiveness of the teaching profession across countries. The first criterion examines expenditure on education as a percentage of GDP, while the second focuses on government expenditure on education. The third criterion analyses the educational attainment of EU residents aged 25–34 years. The fourth criterion considers participation rates in education and vocational training amongst individuals aged 25–64 years. The fifth criterion analyses university graduates’ decisions to pursue teaching careers, and the sixth criterion assesses teachers’ professional satisfaction levels. The seventh criterion compares teachers’ salaries with those of other university-educated professionals, which is complemented by the eighth criterion—a comparison of salary levels for teachers with 15 years of professional experience across OECD countries.

The second research technique employed was a questionnaire survey conducted by our university. The respondents were selected from students enrolled in the bachelor’s study programme “Pedagogy for teachers of practical training”. This programme represents the only pedagogical degree offered by our university and attracts not only teachers of practical subjects at secondary vocational schools or training schools who require formal qualifications for their profession, but also employees from other sectors and self-employed individuals seeking to enter the teaching profession.

The survey included all students enrolled in the programme. This comprehensive approach was feasible due to the programme’s manageable size, with approximately 30–40 students per year of study. Data collection was conducted across four distinct periods: academic years 2014–2015, 2017–2018, 2020–2021, and 2023–2024. The three-year intervals between data collection periods matched the programme’s duration, which ensured complete participant turnover with each cohort participating only once. The total sample comprised 404 respondents.

The questionnaire comprised six questions, with questions 1–3 collecting data on respondents’ year of study, gender, and age. The main focus of the research centred on questions 4–6, which were as follows:

Question 4: What is your position in the labour market?

Question 5: What was the reason for starting your studies at the Institute of Education and Communication?

Question 6: What was the biggest obstacle to studying at the Institute of Education and Communication?

To identify dependencies between data obtained in questions 4–6, the chi-squared test of independence was employed. Where dependence had been statistically confirmed, a more detailed analysis was conducted using the so-called sign scheme. The sign scheme is based on the values of adjusted standardised residuals. When the observed frequency was significantly greater than the expected frequency, a “+” sign was assigned to the cell. Conversely, a “−” sign indicates that the observed frequency was substantially lower than the expected frequency. The number of signs corresponds to the significance level, as presented in

Table 1.

The “0” sign indicates that the difference between observed and expected frequency in the particular cell is statistically insignificant at the 0.05 significance level. All data processing was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics 30.

4. Conclusions

Among the examined occupational categories, employees in education represent the most significant group. The first statistical test revealed that the primary reason for study enrolment among education employees is employer requirements, with non-education employees predominantly citing alternative motivations.

The second statistical test identified time requirements as the most common barrier to study. Although this does not represent a statistically significant dependency for education employees, it is noteworthy that 135 out of 221 education employees cited time constraints as problematic. This finding is particularly concerning given that, according to provisions from Section 24, Paragraph 7 of the Act on Teaching Staff, teaching personnel are entitled to 12 working days of study leave annually (

MEYS, 2024f). Additionally, in accordance with § 232 of the Labour Code, employees are entitled, when furthering their qualifications, to paid leave of absence corresponding to their average earnings. This entitlement covers the time necessary to attend classes, 2 working days for preparing for and taking the examination, 10 working days for preparing for and defending a bachelor’s thesis, and 40 working days for preparing for and taking the final state examination. These provisions apply to all employees, not exclusively to teaching staff.

The persistence of time-related barriers suggests that the formal framework does not translate into practical feasibility in the Czech Republic. The relatively low participation of adults in lifelong learning mirrors international patterns observed in systems where professional learning is not yet fully institutionalised, as also noted in global studies on teachers and personal development (

Ovenden-Hope & Kirkpatrick, 2024).

The second most frequently cited barrier was lack of employer support. While this does not constitute a statistically significant dependency for education employees, the finding that 40 education employees reported inadequate employer support remains concerning, particularly given that employer requests were the predominant motivation for their studies.

The third statistical test revealed no statistically significant relationship between study motivation and perceived barriers. This absence of association can be considered a positive outcome, indicating that employers’ lack of support does not undermine employees’ participation in further education.

According to the fourth line of Strategy 2030+ (the establishment of sustainable financing mechanisms), the Czech Republic aims to enhance the attractiveness of the teaching profession by increasing education funding to OECD average levels. Recent amendments to the Act on Pedagogical Workers have set 130% of the average wage as the compensation for teachers. However, shortcomings persist in teacher professional development, particularly in terms of employer support. A comprehensive international study in 2016 came to similar conclusions: “All the participants had plans for their further professional development but sometimes foresaw hindrances to the realisation of those plans, such as a lack of resources and time” (

Van der Klink et al., 2017).

Continued efforts to enhance motivation among both employers and employees remain necessary. Enhanced tax reliefs for employers represent one potential solution. While costs associated with employee qualification improvement are already tax-deductible under the Labour Code, this applies only when the education relates to the company’s business. Future tax relief provisions could extend to employee education in other areas.

Regional education receives co-financing through European Structural and Investment Funds (hereinafter “ESI”) development programmes. More effective utilisation of these resources could advance pedagogical competence development. Research confirms that “the practice architectures of professional learning in an age of standards work to support instrumental forms of professional learning while constraining the possibility of more authentic or generative forms of professional learning and consequently, teacher professionalism” (

Mockler, 2022).

Understanding different teacher roles will strengthen the entire educational system (

Antonsen et al., 2024), with teacher career system completion representing an integral component. The Czech Republic continues to reform its teacher training systems and support beginning teachers as a priority under Strategy 2030+. Since January 2024, the Teaching Staff Act has implemented mentoring teacher roles. International research indicates that schools can provide enhanced support for beginning teachers (

Mockler, 2022), including mentoring programmes (

Chalies et al., 2021).

Recent changes to accreditation procedures for professional development providers should reduce beginning teacher concerns about the demanding profession while increasing practice motivation. Current solutions rely primarily on ESI project-based support. Strategy 2030+’s second strategic line proposes developing professional standards for teachers and school directors, similar to those implemented in Scotland (

Forde et al., 2016).