1. Introduction

1.1. Global and Policy Context of VET

Vocational education and training (VET) plays a crucial role in ensuring the competitiveness of national economies, strengthening social cohesion, and supporting the employability of future generations. International organisations such as the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization), and the European Union have consistently emphasised that modern VET systems must respond to rapidly changing labour market demands, technological development, and the challenges of lifelong learning (

OECD, 2020;

UNESCO, 2015;

European Commission, 2020). In parallel, international comparative studies and reports such as

Eurydice (

2018) and Cedefop (European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training) (

Cedefop, 2020) point out that VET faces significant structural and cultural differences across Europe, particularly regarding its attractiveness, status, and perceived value among students and their families.

These findings suggest that the effectiveness of VET is not only a matter of curricula or institutional structures, but also of the human resources who mediate between education and the labour market. Among these actors, vocational instructors hold a unique position. They are expected to ensure the transmission of up-to-date professional knowledge and practical competencies while also socialising students into the norms, values, and identities of their respective professions. As a result, the quality of instructor education is widely recognised as a decisive factor in the success and sustainability of VET (

OECD, 2019;

Cedefop, 2017;

Bacsa-Bán, 2021).

1.2. Challenges in Teacher and Instructor Education

Across many education systems, the recruitment and retention of qualified teachers and instructors has become a pressing challenge. International research demonstrates that teacher shortages, high attrition rates, and the declining attractiveness of the profession threaten the stability and quality of education worldwide (

Ingersoll, 2001;

European Commission, 2013). Vocational education faces these challenges in an intensified form, as instructors are required to meet dual expectations: they must possess solid technical expertise from their occupational fields while simultaneously developing pedagogical and psychological competencies for effective teaching (

Grollmann, 2008;

Pilz, 2016;

Bacsa-Bán, 2023).

Studies of teacher education highlight that individuals often enter training with a mixture of intrinsic and extrinsic motivations. While intrinsic factors such as personal interest or a desire to contribute to society are common, extrinsic motives like job security or career advancement also play an important role (

Richardson & Watt, 2006;

Watt & Richardson, 2007). These motivations strongly influence professional identity formation, career persistence, and long-term commitment to teaching (

Engler, 2014;

Bükki, 2022).

For vocational instructor trainees, the transition to an educator role involves reconfiguring an already established professional identity. Having previously worked in technical, economic, or service-related occupations, they often bring strong occupational self-concepts into training. The challenge lies in integrating these prior professional identities with newly acquired teaching competences and pedagogical roles (

Grollmann & Rauner, 2007;

Sappa & Aprea, 2014;

Bacsa-Bán & Cserné Adermann, 2025;

Cserné Adermann & Bacsa-Bán, 2024). Understanding how trainees mobilise their personal resources and navigate this process is therefore central to both research and practice in VET instructor education.

1.3. Positive Psychology and the Character Strengths Framework

In recent decades, positive psychology has become a widely recognised paradigm in educational research, shifting the focus from deficits and weaknesses to the recognition and cultivation of individual strengths (

Seligman & Csíkszentmihályi, 2000). Central to this approach is the taxonomy of character strengths and virtues developed by

Peterson and Seligman (

2004), which identifies 24 strengths clustered under six core virtues: wisdom, courage, humanity, justice, temperance, and transcendence. This framework provides a comprehensive model for understanding how personal resources contribute to wellbeing, resilience, and performance.

Research has shown that character strengths play an important role in education by supporting students’ motivation, engagement, and persistence (

Park & Peterson, 2009;

Quinlan et al., 2012). In teacher education specifically, strengths-based approaches have been associated with enhanced self-efficacy, stronger professional identity, and greater commitment to the teaching profession (

Lavy, 2019;

Niemiec, 2020). Despite these promising results, relatively little attention has been devoted to vocational instructor education, where the dual challenge of integrating occupational expertise with pedagogical competences makes character strengths particularly relevant (

Bacsa-Bán, 2022;

Cserné Adermann & Bacsa-Bán, 2024).

By focusing on the strengths that vocational instructor trainees bring with them at the outset of training, a strengths-based perspective has the potential to foster engagement, identity development, and long-term professional resilience. This approach not only complements existing pedagogical frameworks but also responds to the pressing need to support vocational instructors in a context of growing shortages and high professional demands (

Bacsa-Bán & Cserné Adermann, 2025).

1.4. Research Gap and Aim of the Study

Although international research has extensively examined teacher motivation, professional identity formation, and the role of personal resources in teacher education, relatively few studies have addressed these issues in the specific context of vocational instructor education. This gap is particularly striking in Central and Eastern Europe, where VET systems face unique structural and cultural challenges, and where the social recognition of vocational pathways often lags behind that of general or higher education (

Cedefop, 2020;

Pilz & Li, 2020).

In Hungary, vocational instructor education typically recruits students who already possess professional qualifications and substantial occupational experience. As a result, they enter training with well-developed technical identities but limited pedagogical preparation. The integration of these professional identities with emerging teaching roles is therefore a crucial and complex process, which can strongly influence trainees’ motivation, self-efficacy, and persistence in the programme (

Engler, 2014;

Bükki, 2022). Understanding how character strengths contribute to this transition has both theoretical and practical relevance for improving the quality of instructor preparation (

Bacsa-Bán & Cserné Adermann, 2025;

Cserné Adermann & Bacsa-Bán, 2024).

The present study aims to address this research gap by examining the character strengths of vocational instructor trainees at a Hungarian university across four consecutive cohorts (2021–2024). Using the Values in Action (VIA) character strengths inventory, the study identifies the most prominent strengths among trainees and explores how these strengths may serve as resources for professional identity development and long-term career commitment. By applying a strengths-based perspective, the research aims to contribute to the international literature on vocational instructor education and to provide insights that can inform both policy and practice in the field of VET.

The present study adopts an exploratory, problem-identifying approach to examine how vocational instructor trainees’ character strengths are manifested in the context of teacher education. Rather than testing formal hypotheses, the research focuses on identifying relationships and patterns among character strengths. The study was guided by the following research questions:

RQ1. What are the most prominent character strengths among vocational instructor trainees?

RQ2. How are different strengths interrelated, and do they form coherent clusters?

RQ3. Are there any observable differences in the strengths profiles across cohorts between 2021 and 2024?

RQ4. How can the identified strengths inform vocational instructor education and mentoring practices?

These research questions provided the framework for the data collection and analysis presented in the following sections.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

The present study employed a cross-sectional research design to examine the character strengths of vocational instructor trainees at the beginning of their studies. The investigation covered four consecutive cohorts (2021–2024) of students enrolled in a vocational instructor education program at a Hungarian university. The central aim was to explore the dominant strengths of trainees upon entry and to analyse their potential role in professional identity development and persistence in the programme.

2.2. Participants

Altogether, four cohorts participated in the study. The students came from diverse vocational backgrounds, including technical, economic, and service-oriented professions. Many had already accumulated several years of occupational experience before enrolling in the programme, which typically admits adults who wish to formalise their teaching competencies alongside their professional expertise.

Demographic data were collected to characterise the sample. The gender distribution across cohorts showed a slight predominance of women, although men were also consistently represented. The age distribution reflected the adult learner profile: the majority were between 25 and 45 years old, with smaller groups of both younger entrants (under 25) and older participants (over 45). Cohort sizes varied between the years, with an overall increasing trend in student numbers from 2021 to 2024.

2.3. Instrument

Data were collected using the Values in Action (VIA) Inventory of Strengths developed by

Peterson and Seligman (

2004). This instrument measures 24 distinct character strengths grouped under six universal virtues: wisdom, courage, humanity, justice, temperance, and transcendence. The VIA has been widely validated in psychological and educational research across multiple cultural contexts.

The Hungarian version of the VIA was employed in the present study. This adaptation preserves the structure of the original questionnaire and has demonstrated adequate reliability and validity in Hungarian samples. The instrument provides both individual scores for each of the 24 strengths and aggregate measures for the six overarching virtues, enabling both detailed and comparative analysis.

2.4. Data Collection Procedure

Data were gathered in the first semester of studies, shortly after enrolment. Students completed the questionnaire online under supervised classroom conditions to ensure standardised administration. Participation was voluntary and anonymous, and respondents were assured that their answers would not influence their academic progress. The questionnaire required approximately 30 min to complete.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

The study was conducted in full compliance with the ethical guidelines of the host university and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained from the university’s institutional research ethics committee. Informed consent was secured from all participants prior to the survey. Data were anonymised and processed confidentially.

2.6. Data Analysis

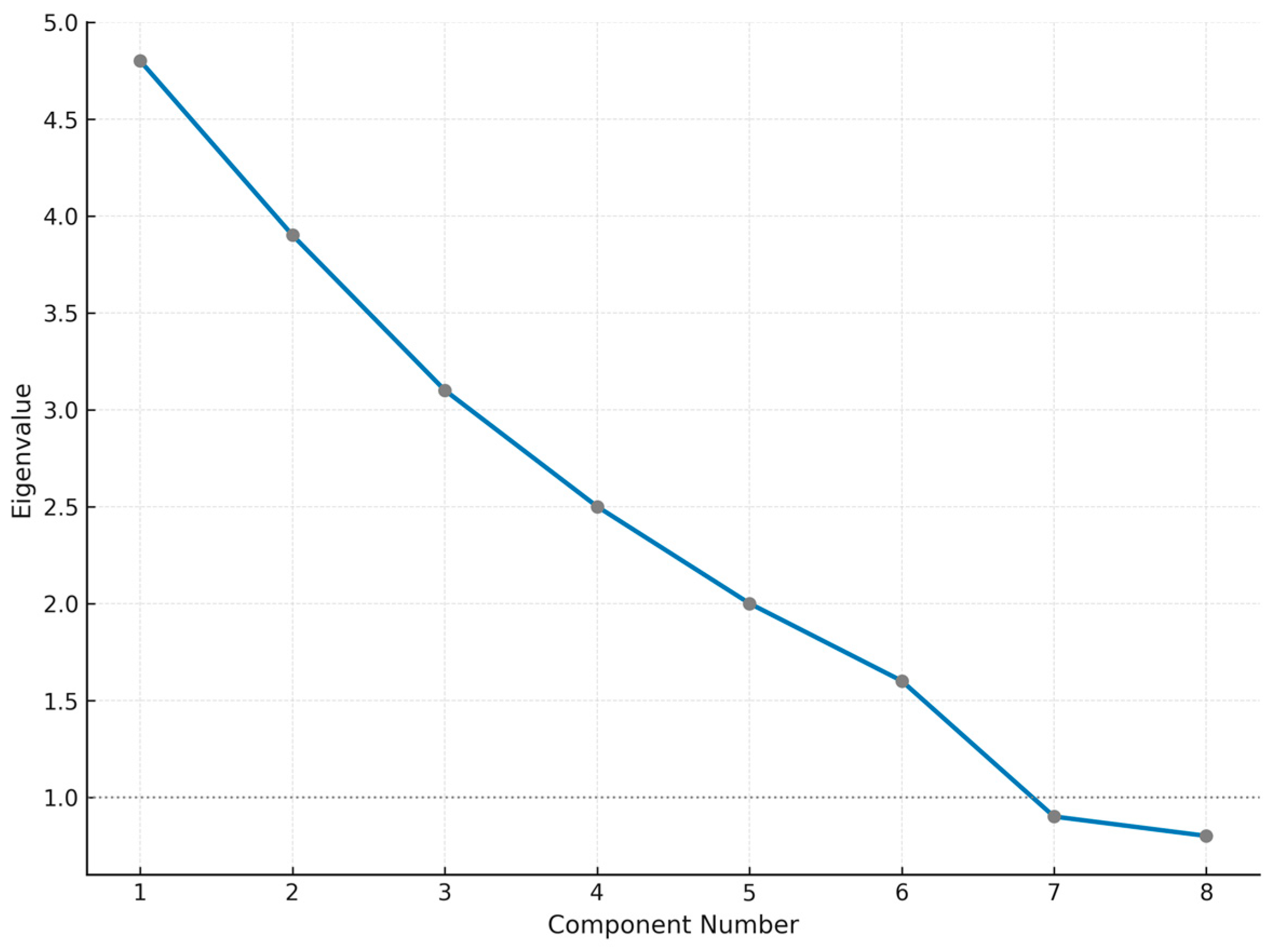

Descriptive statistics were calculated to provide an overview of the sample characteristics and mean scores for each of the 24 VIA character strengths. Pearson correlation analysis was applied to explore the relationships between individual strengths, as the variables were continuous and approximately normally distributed. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to examine potential cohort-level differences across the years 2021–2024. The results of the ANOVA showed no significant group differences (p > 0.05), suggesting that the strengths profiles remained stable over time.

To identify underlying structures among the 24 strengths, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was performed with varimax rotation. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure verified sampling adequacy (KMO = 0.84), and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant (

p < 0.001), confirming the suitability of the data for factor analysis. Components with eigenvalues greater than 1 were retained, and the scree plot inspection suggested a six-factor solution, explaining approximately 60% of the total variance. This result aligns with the theoretical six-virtue framework proposed by

Peterson and Seligman (

2004).

All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics (version 26.0).

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Sample

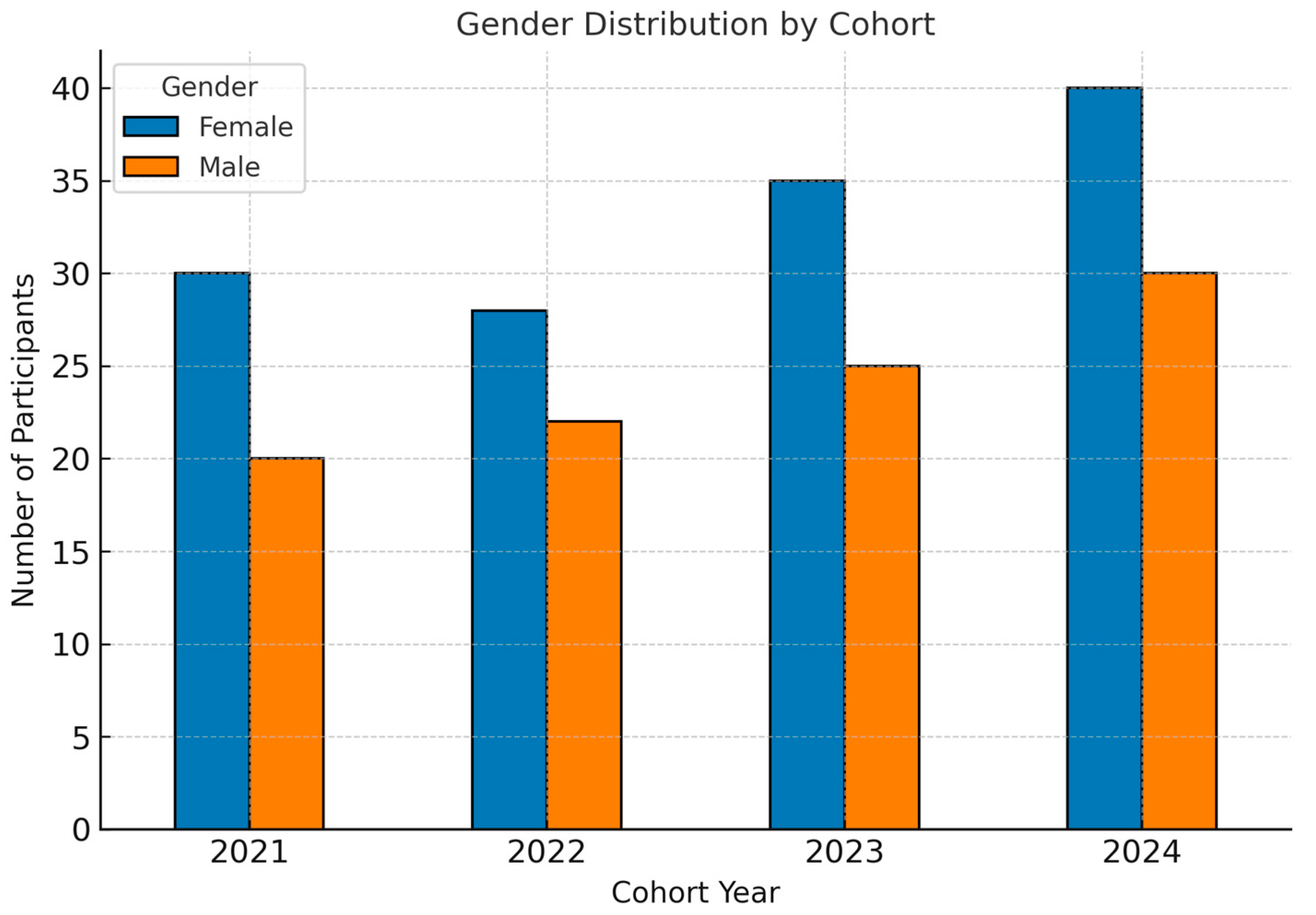

The demographic profile of the four cohorts reflects the adult learner population typical of vocational instructor education in Hungary. Gender distribution shows a slight predominance of female participants, although male trainees were represented in all cohorts (see

Figure 1).

This pattern is consistent with broader European trends in teacher education, where women often outnumber men, particularly in the humanities and service-related vocational fields (

European Commission, 2013;

Engler, 2014).

The age profile indicates that most trainees entered the programme as adult learners with prior occupational experience. The majority were between 25 and 45 years old, suggesting that vocational instructor education often attracts individuals who have already established themselves in their professions and now wish to formalise their teaching role. Smaller groups of younger participants (under 25) and older participants (over 45) were also present, highlighting the heterogeneity of the student body. This diversity in age and professional background provides a rich foundation for the exchange of experiences during training (

Bacsa-Bán, 2021;

Bükki, 2022).

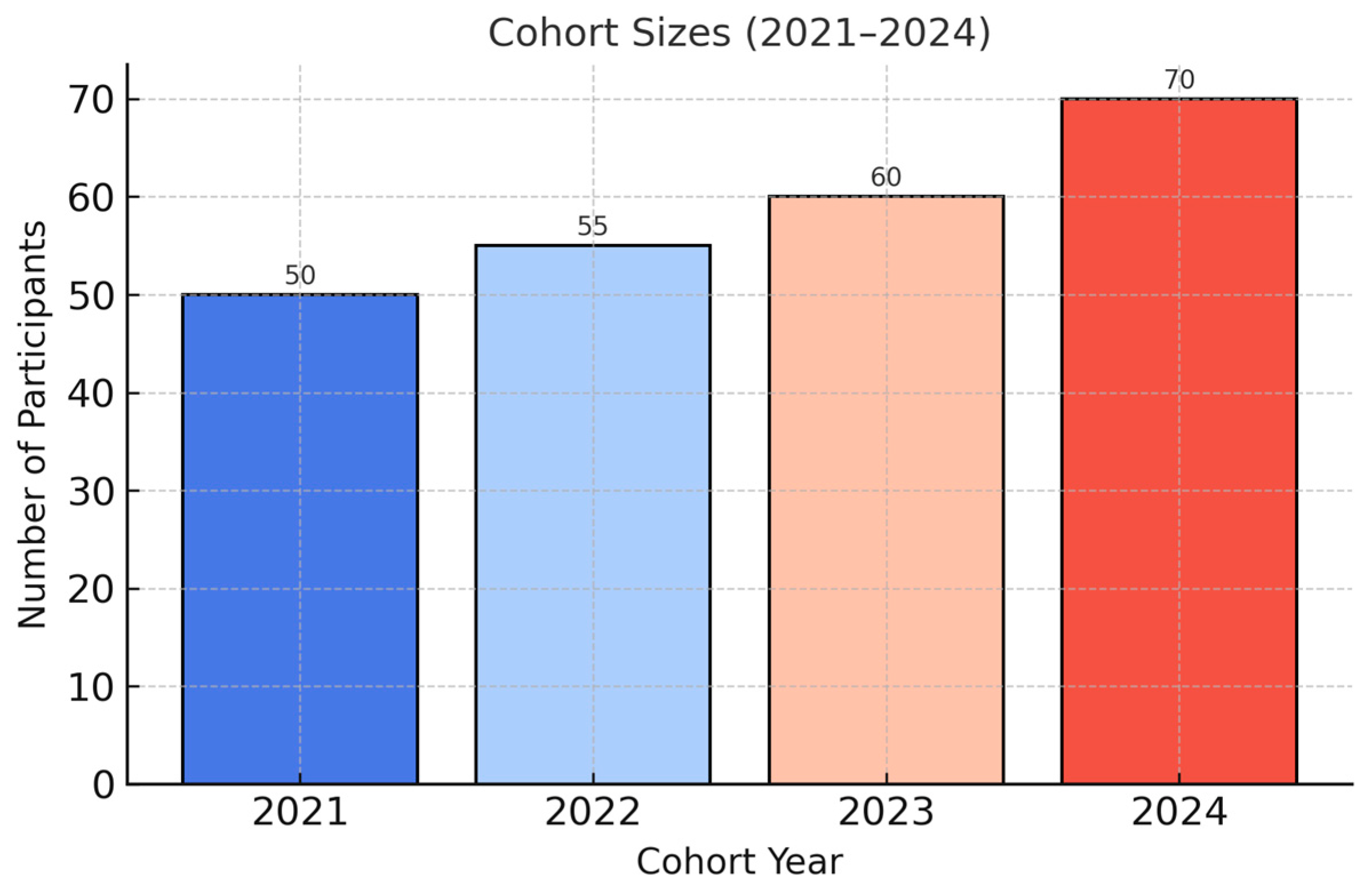

Cohort sizes varied over the four years, with a general increase from 2021 to 2024 (see

Figure 2).

This upward trend reflects both the growing recognition of the importance of vocational instructor education and policy initiatives aimed at strengthening the VET system in Hungary (

Bacsa-Bán & Cserné Adermann, 2025). The variation in cohort sizes also offers a useful perspective for analysing potential differences in strength profiles between smaller and larger groups.

3.2. Overall Distribution of Character Strengths

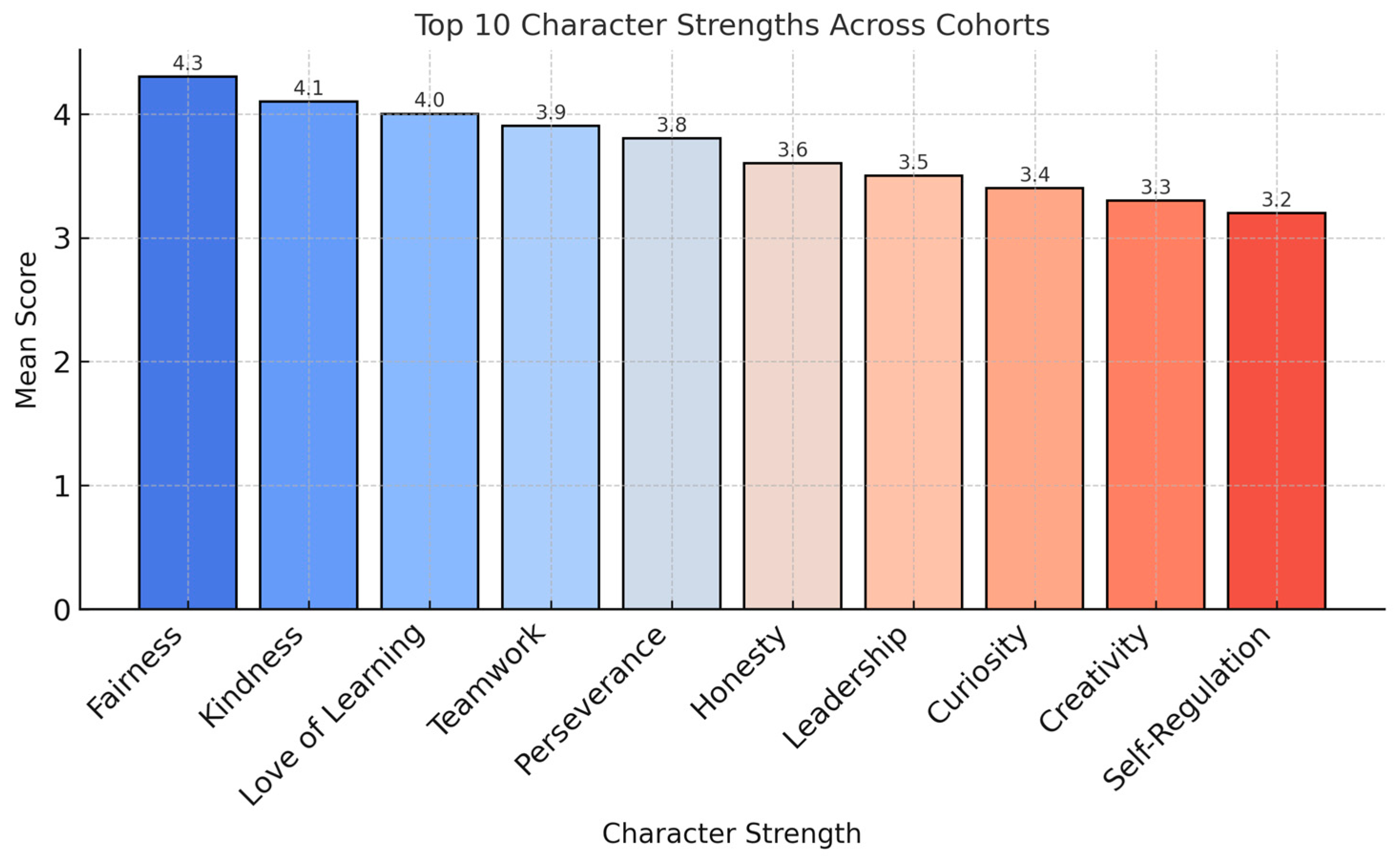

The analysis of the VIA Inventory revealed a consistent pattern of character strengths across the four cohorts. When considering the entire sample, the most prominent strengths were fairness, kindness, love of learning, teamwork, and perseverance (see

Figure 3).

These strengths achieved the highest mean values, indicating that vocational instructor trainees tend to bring with them resources that combine interpersonal sensitivity, intellectual curiosity, and persistence (

Cserné Adermann & Bacsa-Bán, 2024).

Fairness emerged as the single most dominant strength, suggesting that trainees place a high value on justice, impartiality, and treating others equitably. This is particularly relevant in the context of teaching, where instructors are expected to act as mediators and role models for professional ethics. Similar findings have been reported in Hungarian research emphasising the ethical dimension of teaching and the social responsibility of professional educators (

Falus, 2010;

Bacsa-Bán, 2021).

Kindness and teamwork further highlight the importance of interpersonal competencies, which are essential not only for classroom management but also for collaboration with colleagues and employers in dual training systems. Hungarian studies of vocational pedagogy similarly point to the need for cooperation and partnership skills in the VET context (

Engler, 2014;

Bükki, 2022).

Love of learning represents a cognitive strength that directly supports the acquisition of pedagogical knowledge and the continuous updating of technical expertise. Perseverance, as an intrapersonal strength, reflects the ability to sustain effort and overcome challenges—an attribute of special importance in a demanding educational environment that requires balancing occupational, personal, and academic responsibilities (

Bacsa-Bán, 2023).

The distribution of the 24 character strengths further illustrates that, although the five listed above dominate the overall profile, other strengths such as honesty, leadership, and curiosity also play an important role. However, these appeared with somewhat lower mean values. The balance between interpersonal, cognitive, and self-regulatory strengths suggests that trainees enter vocational instructor education with a multidimensional resource base, which may be effectively built upon during training (

Bacsa-Bán & Cserné Adermann, 2025).

3.3. Cohort-Level Comparisons

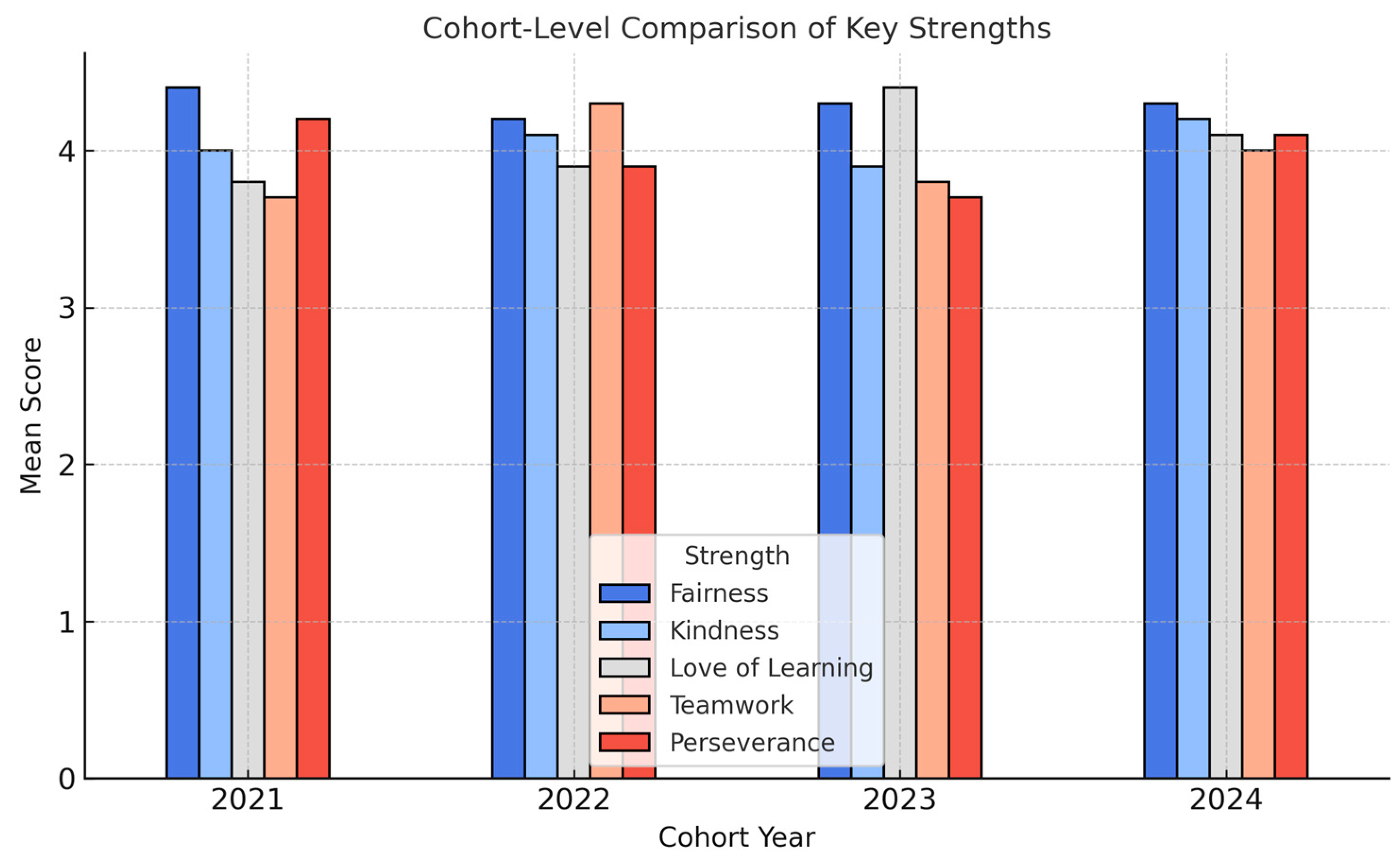

While the overall distribution of strengths was relatively stable across cohorts, certain variations emerged that highlight the dynamic nature of vocational instructor education. These differences may reflect generational factors, the composition of each cohort, or contextual influences related to admission periods.

In the 2021 cohort, perseverance and fairness were particularly pronounced, suggesting that students entering the programme in the first year relied strongly on qualities of endurance and ethical responsibility. This may also indicate the resilience of learners who embarked on training during a period marked by the lingering effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, when uncertainty and adaptability were key resources (

Bacsa-Bán, 2023).

The 2022 cohort, by contrast, showed a higher relative mean in teamwork compared to other years (see

Figure 4).

This finding suggests that group cohesion and collaborative orientation were especially characteristic of this group, which may have been shaped by both the social composition of the cohort and the teaching strategies employed during that academic year (

Engler, 2014;

Bükki, 2022).

In the 2023 cohort, love of learning became more dominant than in earlier groups. This indicates that intellectual curiosity and openness to knowledge were particularly salient among these trainees. The increasing role of digitalisation and the rapid pace of change in vocational fields may have contributed to this emphasis on continuous learning (

Cserné Adermann & Bacsa-Bán, 2024).

Finally, in the 2024 cohort, the profile revealed a balance of the previously dominant strengths, with fairness, perseverance, and kindness all appearing at comparably high levels. This balanced profile may reflect the stabilisation of recruitment patterns in the programme, as vocational instructor education gained wider recognition and popularity over time (

Bacsa-Bán & Cserné Adermann, 2025).

Although the observed cohort differences were not large in magnitude, they suggest that contextual and temporal factors may influence the emphasis placed on certain strengths. These patterns underline the importance of viewing vocational instructor education not only as an individual process but also as one shaped by broader social and institutional contexts (

Durkó, 2004;

Falus, 2010).

3.4. Interrelationships Among Strengths

Beyond identifying the most prominent individual strengths, the analysis also examined how the 24-character strengths related to one another. Correlation analyses revealed several meaningful associations that suggest strengths often appear in clusters rather than as isolated traits. For example, perseverance was strongly correlated with self-regulation, indicating that the ability to sustain effort is closely linked with skills of planning and self-discipline. Similarly, kindness showed significant associations with teamwork and forgiveness, suggesting that interpersonal strengths tend to reinforce one another (

Bacsa-Bán, 2022).

These patterns highlight that vocational instructor trainees do not rely on single strengths in isolation, but rather on interconnected constellations of personal resources. This finding resonates with previous research emphasising that strengths function most effectively when integrated into broader personality and identity structures (

Park & Peterson, 2009;

Lavy, 2019;

Bacsa-Bán & Cserné Adermann, 2025).

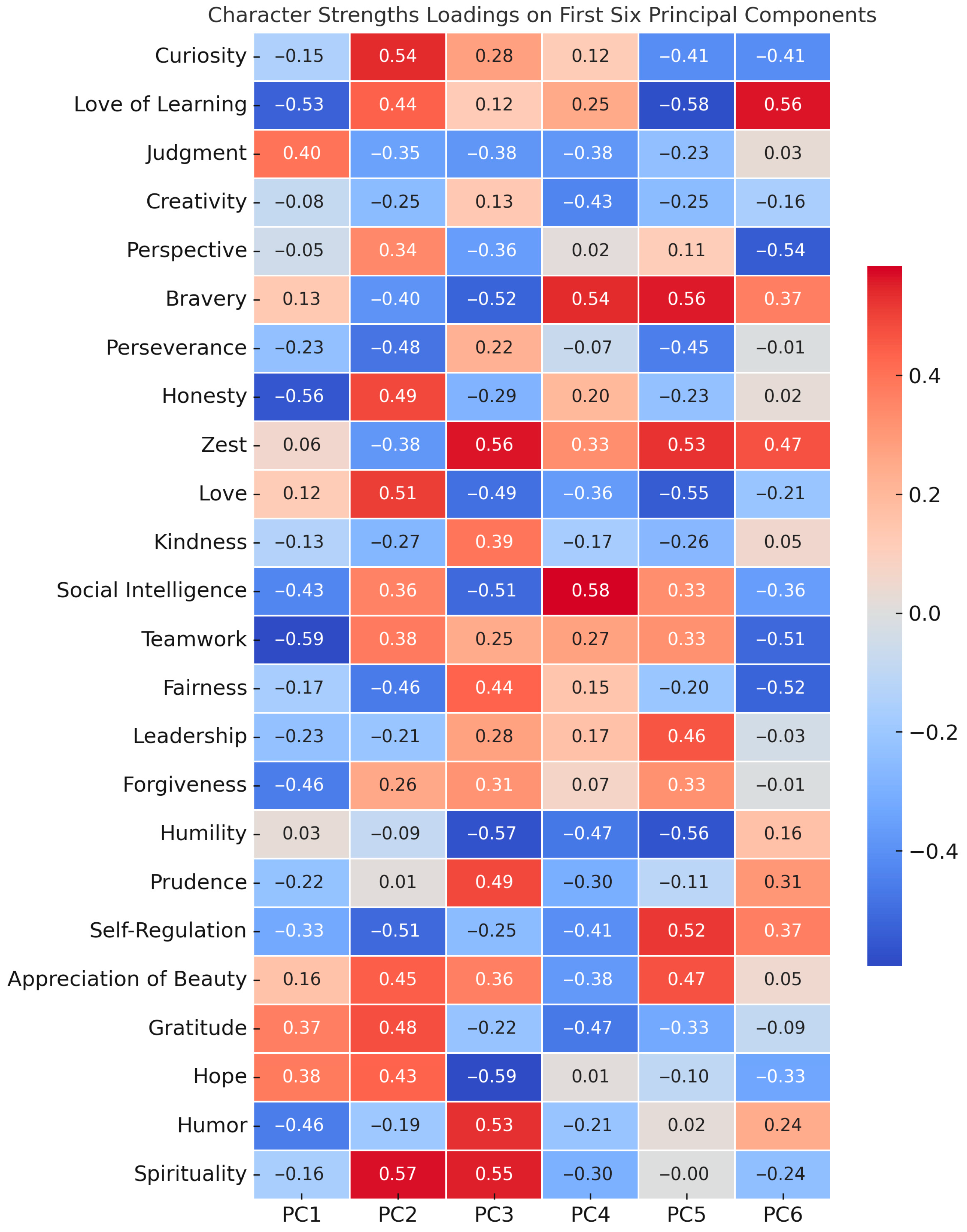

To explore these interrelationships more systematically, a principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted. The results indicated that the 24 strengths could be grouped into a smaller number of latent dimensions, largely aligning with the six higher-order virtues proposed by

Peterson and Seligman (

2004). For instance, strengths such as curiosity, creativity, and love of learning loaded together on a component corresponding to wisdom, while teamwork, kindness, and fairness clustered under humanity and justice (see

Figure 5).

Hungarian studies have similarly emphasised the significance of holistic personality development and the interconnection of competencies in vocational and teacher education (

Falus, 2010;

Engler, 2014).

This dimensional structure suggests that vocational instructor trainees’ strengths are not randomly distributed but organised into broader categories that may play a role in shaping professional identity. From a pedagogical perspective, this implies that strengthening one cluster of traits may have a reinforcing effect on related strengths, providing a more holistic approach to personal development in instructor education (

Cserné Adermann & Bacsa-Bán, 2024).

3.5. ANOVA and Correlation Findings

A one-way ANOVA was performed to examine cohort-level differences among vocational instructor trainees who entered the programme between 2021 and 2024. The analyses revealed no statistically significant differences in mean scores for any of the 24 character strengths (all p > 0.05). These findings indicate that the strengths profiles remained stable across cohorts, suggesting a consistent pattern of character-strength manifestations over time.

Pearson correlation analysis was used to explore the interrelations among the 24 character strengths. Strong positive correlations were found between perseverance and integrity (r = 0.97,

p < 0.001), and between kindness and teamwork (r = 0.89,

p < 0.001). Moderate associations were observed between curiosity and love of learning (r = 0.39,

p < 0.001), and between humility and prudence (r = 0.31,

p < 0.01). These results confirm that certain strengths tend to co-occur and may represent higher-order domains such as self-regulation, interpersonal engagement, and cognitive openness.

Table 1 presents the Pearson correlation coefficients among the main character strengths, highlighting the strongest associations.

Principal Component Analysis (PCA) with varimax rotation identified six latent components with eigenvalues greater than 1, explaining approximately 60% of the total variance. The first three components represented cognitive, interpersonal, and self-regulatory strengths, while the remaining three reflected affective, motivational, and civic orientations. These results align with the six-virtue model proposed by

Peterson and Seligman (

2004), confirming that the VIA framework can be meaningfully applied in vocational instructor education.

Figure 6 presents the scree plot illustrating the proportion of variance explained by each component. The eigenvalue “elbow” at the sixth factor supports the six-factor solution, consistent with the six-virtue model proposed by

Peterson and Seligman (

2004).

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Key Findings

The study investigated the character strengths of vocational instructor trainees across four cohorts in Hungary, offering insights into how personal resources shape the early stages of professional identity development. The analysis revealed several consistent patterns: trainees entered with a profile dominated by fairness, kindness, love of learning, teamwork, and perseverance, strengths that collectively reflect ethical commitment, interpersonal sensitivity, intellectual curiosity, and resilience (

Bacsa-Bán, 2021;

Bacsa-Bán, 2022).

Cohort-level comparisons indicated minor but noteworthy differences: teamwork was more salient in the 2022 cohort, while love of learning became more pronounced in the 2023 group, and the 2024 cohort displayed a more balanced strengths profile. These variations suggest that contextual and temporal factors may influence the prominence of certain strengths (

Engler, 2014;

Bükki, 2022).

Finally, correlation analyses and PCA highlighted that character strengths are organised into broader constellations corresponding to

Peterson and Seligman’s (

2004) six virtues, confirming that trainees’ resources are multidimensional rather than fragmented. This holistic pattern aligns with Hungarian pedagogical research emphasising that vocational and teacher education should focus not only on isolated competences but also on integrated personality development (

Falus, 2010;

Cserné Adermann & Bacsa-Bán, 2024;

Bacsa-Bán & Cserné Adermann, 2025). These findings further confirm that the six-factor structure identified through PCA is consistent with the VIA framework and the six virtues proposed by

Peterson and Seligman (

2004), providing a robust theoretical foundation for interpreting the strengths-based profile of vocational instructor trainees.

The results confirm that character strengths can be identified among vocational instructor trainees and can serve as reliable indicators of personal and professional resources in the context of teacher education. This interpretation reinforces the theoretical assumption that strengths are not fixed personality traits but develop through reflective practice, social interaction, and professional experience during teacher preparation.

4.2. Comparison with International Literature

The prominence of fairness, kindness, and teamwork among vocational instructor trainees aligns with findings from international studies highlighting the central role of interpersonal and ethical strengths in teacher education. For instance,

Watt and Richardson (

2007) emphasised that prosocial motives such as helping others and contributing to society are strong predictors of commitment to teaching. Similarly,

Grollmann (

2008) and

Pilz (

2016) observed that the dual role of vocational instructors—mediating between the world of work and education—requires a heightened sensitivity to fairness and collaboration, qualities that were strongly reflected in the present study (

Bacsa-Bán, 2021).

The strong presence of love of learning resonates with research by

Park and Peterson (

2009) and

Lavy (

2019), who reported that intellectual curiosity and openness to knowledge are central to sustaining motivation in teaching. This is particularly relevant in VET, where instructors must continuously update their technical expertise in rapidly evolving occupational fields. The elevated scores for love of learning in the 2023 cohort may also reflect broader societal shifts, including the increasing importance of digitalisation and lifelong learning, themes frequently noted in recent OECD and Cedefop reports (

OECD, 2020;

Cedefop, 2020;

Cserné Adermann & Bacsa-Bán, 2024).

The finding that perseverance and self-regulation are closely associated supports earlier studies showing that self-regulatory capacities are essential for teachers’ resilience and professional sustainability (

Quinlan et al., 2012;

Niemiec, 2020). Hungarian contributions have similarly pointed out the importance of self-regulation and reflective practice in teacher and instructor education, emphasising their role in shaping professional identity and persistence in training (

Engler, 2014;

Bükki, 2022).

At the same time, the study highlights a research gap: although the strengths-based approach has been applied in general teacher education, relatively little is known about its specific role in vocational instructor education. By situating the Hungarian results within this international framework, the present research adds new empirical evidence to a field that remains underexplored in both Western and Central–Eastern European contexts (

Durkó, 2004;

Bacsa-Bán, 2023).

4.3. Implications for Vocational Instructor Education

The results of this study hold several important implications for the design and delivery of vocational instructor education programmes. Consistent with the findings of

Niemiec (

2020) and

Biswas-Diener et al. (

2011), strengths-based reflection can be integrated into teacher training to enhance motivation, professional identity, and resilience. Integrating strengths-based reflection into training can enhance motivation, resilience, and self-efficacy among trainees. Structured reflection activities, peer mentoring, and feedback sessions focusing on the recognition and application of personal strengths can foster deeper professional identity development. Such practices also promote a culture of collaboration and positive feedback within training institutions, contributing to long-term professional wellbeing.

The results of this study hold several important implications for the design and delivery of vocational instructor education programmes. First, the consistent dominance of fairness, kindness, teamwork, love of learning, and perseverance suggests that trainees bring with them a robust set of interpersonal, cognitive, and self-regulatory resources. These strengths can be intentionally leveraged in training curricula to foster professional identity development. For example, fairness and teamwork can be integrated into collaborative learning tasks, role plays, and reflective exercises that highlight the ethical and social dimensions of teaching (

Bacsa-Bán, 2021;

Falus, 2010).

Second, the prominence of love of learning provides a strong foundation for encouraging continuous professional development. By designing curricula that promote inquiry-based learning and critical reflection, programmes can channel trainees’ intellectual curiosity into the acquisition of pedagogical knowledge and the updating of occupational expertise. Such an approach aligns with international calls for strengthening lifelong learning in vocational education (

OECD, 2020;

UNESCO, 2015;

Cserné Adermann & Bacsa-Bán, 2024).

Third, the significant role of perseverance and self-regulation indicates that vocational instructor training should also provide structured opportunities for trainees to develop resilience and coping strategies. This aligns with research by

Govindji and Linley (

2007), who emphasised that the awareness and use of one’s character strengths enhances self-efficacy and goal attainment. These qualities are especially relevant given the high demands of VET teaching, which often involves balancing school-based and workplace-based instruction, as well as responding to diverse learner needs. Embedding stress management, time management, and resilience training modules could further support trainees’ long-term career persistence (

Engler, 2014;

Bükki, 2022;

Bacsa-Bán, 2023).

Finally, the identification of strength constellations through PCA suggests that professional development efforts may benefit from focusing on clusters of related strengths rather than isolated traits. This implies that training interventions can be designed to strengthen broader dimensions—such as humanity, justice, or wisdom—that have reinforcing effects across multiple character strengths. Such a holistic, strengths-based approach could not only enhance trainees’ personal growth but also contribute to the quality and attractiveness of the VET teaching profession as a whole (

Durkó, 2004;

Bacsa-Bán & Cserné Adermann, 2025), ultimately supporting their long-term wellbeing and flourishing (

Peterson & Seligman, 2004).

4.4. Limitations of This Study

While the present study provides valuable insights into the character strengths of vocational instructor trainees, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the research was conducted within a single Hungarian university, which may limit the generalisability of the findings.

Second, the study employed a cross-sectional design, which captures strengths profiles at a single point in time—namely, upon entry into the programme. This design does not allow for conclusions regarding how strengths develop during the course of training or how they influence career persistence in the long term.

Third, the research relied exclusively on self-report data collected through the VIA Inventory. While this instrument is widely validated, self-reported measures may be influenced by social desirability or individual response tendencies. Combining self-reports with qualitative methods such as interviews, reflective journals, or peer assessments could provide a richer understanding of trainees’ strengths and their role in professional identity formation (

Cserné Adermann & Bacsa-Bán, 2024).

Finally, while the study applied quantitative analyses, the integration of mixed-method approaches could yield deeper insights into how trainees perceive and apply their strengths in real educational contexts. Future studies might also consider using the VIA Classification of Character Strengths (

VIA Institute on Character, 2020) as a comparative framework to ensure consistency across contexts.

Overall, the discussion above highlights how character strengths function both as individual resources and as collective values in vocational instructor education. The findings form the conceptual foundation for the

Section 5, which summarises the study’s contributions and outlines directions for future research.

5. Conclusions

This study examined the character strengths of vocational instructor trainees and explored how these strengths cluster into broader dimensions. The results revealed six components—cognitive, interpersonal, self-regulatory, affective, motivational, and civic—that correspond to the VIA model and demonstrate that strengths-based profiles can be meaningfully identified in vocational teacher education.

Rather than testing hypotheses, the research adopted an exploratory, problem-formulating approach to reveal how personal strengths function as developmental resources in the process of becoming a vocational instructor. This contributes to the growing body of literature on positive education by extending the strengths-based perspective to vocational and professional training contexts.

In practical terms, the findings highlight that integrating reflection on personal strengths into instructor education may enhance motivation, resilience, and professional identity formation. Based on these findings, VET teacher educators should intentionally integrate strengths-based reflection, mentoring, and feedback into their training courses. They should help trainees identify and apply their character strengths in teaching practice, encourage peer collaboration, and model the use of positive psychology principles in pedagogical design. Such practices can foster more positive, collaborative learning environments and strengthen the long-term attractiveness of the VET teaching profession.

Despite its contributions, the study is limited by its national scope and cross-sectional design. Future research should include longitudinal and cross-national comparisons to explore how strengths evolve over time and across cultural contexts.

Overall, the study emphasises the value of recognising and developing character strengths as a foundation for both individual wellbeing and professional growth in vocational instructor education.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.B.-B. and G.C.A.; methodology, A.B.-B. and G.C.A.; software, A.B.-B.; validation, A.B.-B. and G.C.A.; formal analysis, A.B.-B., G.C.A., and M.B.; investigation, A.B.-B. resources, G.C.A.; data curation, A.B.-B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.B.-B. and G.C.A.; writing—review and editing, A.B.-B., G.C.A., and M.B.; visualisation, A.B.-B. and G.C.A.; supervision, A.B.-B. and G.C.A.; project administration, A.B.-B. and G.C.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Dunaújváros (protocol code DUE-KB-2/2025, with approval granted on 23 September 2025).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Similarly, written informed consent has been obtained from the participants to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| Cedefop | European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training |

| OECD | Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| UNESCO | United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization |

| VET | Vocational Education and Training |

| VIA | Values in Action |

References

- Bacsa-Bán, A. (2021). Challenges and opportunities in vocational instructor education. DUE Press. (In Hungarian) [Google Scholar]

- Bacsa-Bán, A. (2022). Strengths-based pedagogy in vocational instructor training. MELLearN. (In Hungarian) [Google Scholar]

- Bacsa-Bán, A. (2023). Resilience and identity in adult learning. JATE Press. (In Hungarian) [Google Scholar]

- Bacsa-Bán, A., & Cserné Adermann, G. (2025). Holistic approaches in vocational teacher education: A strengths-based perspective. University of Debrecen Press. (In Hungarian) [Google Scholar]

- Biswas-Diener, R., Kashdan, T. B., & Minhas, G. (2011). A dynamic approach to psychological strength development and intervention. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 6(2), 106–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bükki, E. (2022). Student motivation and self-regulation in teacher education. Eötvös Lorand University. (In Hungarian) [Google Scholar]

- Cedefop. (2017). The changing nature and role of vocational education and training in Europe. Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Cedefop. (2020). Vocational education and training in Europe 1995–2035: Scenarios for European vocational education and training. Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Cserné Adermann, G., & Bacsa-Bán, A. (2024). Positive pedagogy and lifelong learning in vocational education (Vol. 12, pp. 45–67). MELLearN Books. (In Hungarian) [Google Scholar]

- Durkó, M. (2004). Borderlands between andragogy and pedagogy. Gondolat Publishing. (In Hungarian) [Google Scholar]

- Engler, Á. (2014). Motivation and student pathways in teacher education. University of Debrecen Press. (In Hungarian) [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. (2013). Supporting teacher educators for better learning outcomes. European Commission. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. (2020). European skills agenda for sustainable competitiveness, social fairness and resilience. European Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Eurydice. (2018). The teaching profession in Europe: Practices, perceptions, and policies. Education, Audiovisual and Culture Executive Agency. [Google Scholar]

- Falus, I. (2010). Methodology of pedagogical research. National Textbook Publishing. (In Hungarian) [Google Scholar]

- Govindji, R., & Linley, P. A. (2007). Strengths use, self-concordance and well-being: Implications for strengths coaching and coaching psychologists. International Coaching Psychology Review, 2(2), 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grollmann, P. (2008). The quality of vocational teachers: Teacher education, institutional roles and professional reality. European Educational Research Journal, 7(4), 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grollmann, P., & Rauner, F. (2007). International perspectives on teachers and trainers in technical and vocational education. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Harzer, C., & Ruch, W. (2013). The application of signature character strengths and positive experiences at work. Journal of Happiness Studies: An Interdisciplinary Forum on Subjective Well-Being, 14(3), 965–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingersoll, R. (2001). Teacher turnover and teacher shortages: An organizational analysis. American Educational Research Journal, 38(3), 499–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavy, S. (2019). A strengths-based approach to teacher learning: The use of character strengths in supporting teacher well-being and professional identity. Teaching and Teacher Education, 77, 117–127. [Google Scholar]

- Niemiec, R. M. (2020). Character strengths interventions: A field guide for practitioners. Hogrefe. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2019). Teachers and school leaders as lifelong learners. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- OECD. (2020). Vocational education and training in a changing world. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Park, N., & Peterson, C. (2009). Character strengths: Research and practice. Journal of College and Character, 10(4), 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pilz, M. (2016). Training teachers for vocational education: A comparative perspective. European Journal of Education, 51(2), 203–216. [Google Scholar]

- Pilz, M., & Li, J. (2020). Comparative research on vocational education and training: Methodological considerations. European Educational Research Journal, 19(3), 249–264. [Google Scholar]

- Quinlan, D., Swain, N., & Vella-Brodrick, D. (2012). Character strengths interventions: Building on what we know for improved outcomes. Journal of Happiness Studies, 13(6), 1145–1163. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, P. W., & Watt, H. M. G. (2006). Who chooses teaching and why? Profiling characteristics and motivations across three Australian universities. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 34(1), 27–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sappa, V., & Aprea, C. (2014). Teachers’ professional identity development in vocational education: A cross-cultural perspective. International Journal for Research in Vocational Education and Training, 1(1), 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Seligman, M. E. P., & Csíkszentmihályi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55(1), 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- UNESCO. (2015). Re-thinking education: Towards a global common good? UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- VIA Institute on Character. (2020). The VIA classification of character strengths. VIA Institute on Character. Available online: https://www.viacharacter.org (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Watt, H. M. G., & Richardson, P. W. (2007). Motivational factors influencing teaching as a career choice: Development and validation of the FIT-choice scale. Journal of Experimental Education, 75(3), 167–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).