Abstract

In Georgia (Sakartvelo), a program promoting bilingual education in preschool institutions was formally adopted in 2020. It aligns with the objectives of the 2021–2030 State Strategy for Civic Equality and Integration Plan, which envisions a comprehensive reform of bilingual education across Georgia’s regions. Any reform requires research and evaluation to measure how effectively it is being implemented and whether the intended outcomes have been achieved. The bilingual education initiative pursues a dual objective: to preserve the native languages of minority communities while ensuring effective acquisition of the state language. This dual mandate is intrinsically linked to state language policy and constitutes a sensitive issue for local communities, parents, and preschool administrators, thereby necessitating a careful and nuanced approach. The present study analyzed the readiness of the social environment to support the implementation of bilingual education programs at the preschool level in the regions of Georgia in which ethnic minorities live side by side. Research was carried out in two ethnically diverse regions—Kvemo Kartli and Samtskhe–Javakheti. The author conducted individual and group interviews, and the elicited data were analyzed with the help of content and thematic analyses. This study examines key attributes of the ongoing preschool reform to identify factors that facilitate the effective implementation of early bilingual education initiatives. The findings highlight both commonalities and regional variations in parental attitudes toward the bilingual education reform.

1. Introduction

Georgia (Sakartvelo) is a country of ethnic, linguistic, cultural, and religious diversity, and it actively protects the identity of each citizen. Assessing multilingual education in the Republic of Georgia involves considering its historical, sociopolitical, linguistic, and educational contexts. Georgia presents a special case due to its unique Caucasian language, specific alphabet, geopolitical space, ethnic and linguistic diversity, its post-Soviet nation-building project, and its efforts to balance national unity with minority rights.

A high level of economic migration driven by globalization, as well as ongoing wars and armed conflicts, has shaped the current political agenda related to minority rights. Many governments and the international community have come to acknowledge that cultural diversity and minorities’ desire to safeguard their rights are fundamental aspects of contemporary society. This recognition began in the aftermath of World War II, marked by the establishment of a robust international legal framework. The founding of the United Nations (UN) in 1942, the Council of Europe in 1949, and the subsequent development of international legal instruments provided momentum for advancing human rights and global cooperation (Kevlishvili et al., 2005). Since then, the protection of human rights has become a shared responsibility and a central focus of governmental and international bodies. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, Georgia became actively involved in these processes.

In the global perspective, minority integration is viewed through a legal lens as the right to education and participation in economic life. This is articulated in Article 15 of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities—a comprehensive treaty adopted by the Council of Europe in 1994 that is now in force in 38 states (https://www.coe.int/en/web/minorities/at-a-glance, accessed on 27 June 2025). This article emphasizes not only the elimination of discrimination and the protection of formal equality but also the implementation of effective measures to ensure genuine inclusion in educational, economic, and social life (Phillips, 2005, pp. 287–306). It is important to highlight that under international human rights law, these rights are considered to be interconnected and of equal importance, forming a comprehensive and indivisible framework. Georgia joined the convention in 2005, committing itself to respecting minority identities and creating conditions for the maintenance of their rights. The current State Strategy for Civic Equality and Integration Plan covers the period from 2021 to 2030 and aims to ensure effective integration policies through the protection of ethnic diversity (https://smr.gov.ge/uploads/Files/_%E1%83%98%E1%83%9C%E1%83%A2%E1%83%94%E1%83%92%E1%83%A0%E1%83%90%E1%83%AA%E1%83%98%E1%83%90/Concept_ENG21.12.pdf, accessed on 27 June 2025). The state focuses on creating equal opportunities for all citizens, regardless of ethnic or cultural backgrounds (e.g., Tabatadze, 2021).

These national and international documents stipulate that ethnic minorities should be provided with the opportunity to advocate collectively for their social rights in collaboration with the local communities (Isakadze, 2023). This inclusive approach serves as a crucial foundation for the social and economic advancement of the country as a whole. Furthermore, the international community has taken additional steps by introducing tools to assess countries’ performance in managing cultural diversity, notably through the development of the Multiculturalism Policy Index (MCP Index, 2025), also known as the Kymlicka Index (see, e.g., Kymlicka, 2007; Migration Policy Hub, 2011). Among the different indicators used in this index, two specifically relate to education: one of them assesses the extent to which multiculturalism is reflected in the school curriculum; the other evaluates the level of funding allocated to bilingual education. The government of Georgia is determined to preserve the identities of national minorities, including their religion, language, culture, and traditions. The constitution guarantees equality among citizens regardless of ethnicity, religion, or language, allowing everyone to preserve and develop their culture and use their native language in both private and public life. Civic engagement and political participation are encouraged, ensuring that minorities are involved in the country’s social and political life.

It is widely acknowledged that children’s education significantly influences the degree and quality of ethnic minority integration and serves as one of its defining characteristics. The importance of education is underscored by the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child, which asserts that “access to education is becoming a key instrument of social benefits and development in the future.” (UNESCO, 2019).

One of the most pressing challenges in preschool education in regions densely populated by ethnic minorities is the effective teaching of the state language. Over the years, the Ministry of Education and Science has implemented several programs aimed at teaching Georgian as a second language. Notably, in 2020, a program promoting bilingual education in preschool institutions was approved. This initiative, aligned with the state strategy for civic equality, seeks to reform bilingual education practices in these regions. As with any innovation, such reforms require systematic research and evaluation. However, there remains a significant gap between the stipulated goals and facts on the ground, and it is this problem that this paper seeks to address.

The purpose of this study is to evaluate how external, system-level, proximal, and community-level factors support or hinder the implementation of preschool bilingual education aimed at developing state-language (Georgian) proficiency among children from ethnic minority communities in Kvemo Kartli and Samtskhe–Javakheti. This study focuses on three interacting levels: state policy and its implementation mechanisms; municipal governance and kindergarten management; and practices and attitudes of educators, bilingual assistants, parents, and local communities.

The research questions are as follows: RQ1. To what extent do national legal and strategic frameworks for minority rights and bilingual preschool education (laws, standards, and strategies) align with implementation processes at municipal and institutional levels? RQ2. What administrative procedures, staffing models (including bilingual assistants), training, and monitoring mechanisms are in place in pilot kindergartens, and how do they facilitate or constrain state-language learning for minority children? RQ3. How do parents, caregivers, and local communities perceive and support bilingual preschool education, and what forms of collaboration with educators occur in practice? RQ4. What changes do stakeholders report in children’s participation, exposure to Georgian, and readiness for transition to primary school as a result of the pilot? What barriers persist?

Georgia has robust human rights commitments and minority protection frameworks; teaching Georgian as a second language is a long-standing challenge, and bilingual preschool reforms began only recently, with uneven implementation. This study provides one of the first multi-level qualitative assessments of the preschool bilingual-education pilot in two minority-dense regions, triangulating policy analysis with stakeholder interviews and focus groups to reveal the specific policy–practice gaps and the conditions under which implementation succeeds.

2. Context of This Study

Georgia (Sakartvelo) is a democratic republic where the official language is Georgian, and in the Autonomous Republic of Abkhazia, both Georgian and Abkhazian are official languages. According to the latest data from the National Statistics Office of Georgia (Geostat, 2017), ethnic minorities make up 13.2% of the population. They include Abkhazians, Armenians, Assyrians, Azerbaijanis, Avars, and other peoples of Dagestan, as well as Czechs, Estonians, Germans, Greeks, Jews, Kurds, Latvians, Lithuanians, Ossetians, Poles, Roma, Russians, Vainakhs, Udins, Ukrainians, and Yezidis. Georgia’s ethnic and religious diversity is seen as a national treasure, and the peaceful coexistence of different ethnic groups over centuries has been a source of pride.

The largest ethnic minority groups in Georgia are Azerbaijanis and Armenians. According to the 2014 census conducted by the National Statistics Office, there are approximately 284,761 ethnic Azerbaijanis, making up 6.5 per cent of the total population. Armenians constitute 5.7 per cent of the population, totaling 248,929 individuals. Azerbaijanis primarily reside in regions such as Kvemo Kartli, where they formed 45 per cent of the population in 2002. Armenians are the majority in areas like Akhalkalaki, Ninotsminda, and Tsalka (the latest census of 2014 is analyzed in Geostat, 2017).

The settlement patterns of ethnic minorities in Georgia are as follows: Armenians in Samtskhe–Javakheti; Azerbaijanis in Kvemo Kartli; Kists in the Pankisi Gorge; Ossetians in the Lagodekhi Municipality; and Russians, Kurds, Yezidis, and Roma in Batumi and Tbilisi. In the Soviet era, the language of interethnic communication was Russian (cf. Chachanidze & Guchua, 2024). It served as the lingua franca and dominated education; minority languages were marginalized or maintained in limited contexts. In the post-1991 independent Georgia, a shift to Georgian as the sole state language took place, with efforts to build a strong national identity, which sometimes resulted in tensions between language policy, ethnic minorities, and social integration (cf. Gorgadze, 2016).

Multilingual education in Georgia is often asymmetrical (Misachi, 2017). Minorities (Armenians, Azerbaijanis, etc.) may be bilingual (native language + Georgian or Russian), but many have limited proficiency in Georgian, affecting or limiting their access to higher education and white-collar jobs. Russian remains a highly prestigious language for many minorities, but it is no longer promoted by the state. The insufficient proficiency in Georgian remains a significant obstacle to full integration into the country’s civic and political life. The government’s main goals include democratic development, expanding socio-economic opportunities, and integration into Europe and Euro-Atlantic treaties. The latter requires that fundamental human rights be observed, paving the way to building an equitable society. In its laws and documents, the government values cultural diversity and contributions of ethnic minorities to socio-economic life as key factors of the country’s sustainable development. State policy promotes full integration, cultural diversity, and a fair, safe, and tolerant environment, which should ensure equal rights and opportunities for all citizens. State policies also aim to preserve and develop the cultural identity of ethnic minorities, including language, traditions, creativity, and cultural heritage. Key tasks include discussions on the role of minorities in cultural policy, protection and promotion of minority cultural heritage, and encouragement of cultural diversity (Gabunia et al., 2022). Efforts to achieve these goals involve caring for the material and intangible cultural values of ethnic minorities, such as creating an inventory and professional descriptions of cultural monuments, supporting theaters and museums, and using libraries for intercultural members of the minority groups, especially the youth.

Despite significant progress in integrating ethnic minorities into civic life, challenges remain. The 2020 State Strategy for Civic Equality and Integration outlines a plan to address these challenges, emphasizing access to quality education as a priority. Multi-level courses of the Georgian language are offered to civil servants and to those seeking higher and vocational education. Efforts have been made to raise the effectiveness of teaching the state language to the minorities.

In contrast to the general education sector, empirical research on the preschool level in Georgia remains limited, particularly considering that the implementation of bilingual education at this stage constitutes a relatively recent policy development. This study aims to examine the role of external factors—specifically, the engagement of kindergarten staff, behavior of the local community, and families in support of the acquisition of the state language by preschoolers in the regions predominantly inhabited by ethnic minorities in the context of the ongoing bilingual education reform.

3. Theoretical Framework: Bilingual Education in Early Childhood

Bilingual education (preschool) is understood as the structured use of the home/minority language alongside systematic, developmentally appropriate exposure to the state language to support linguistic, cognitive, and socio-emotional development. Research on bilingual education has long emphasized the dual mandate of supporting children’s heritage or minority languages while ensuring mastery of the majority or state language (Cummins, 2000; García, 2009; Hornberger, 2003; May, 2013). These goals are often in tension: while early bilingual education can foster multilingual competence, cultural continuity, and cognitive flexibility (Bialystok, 2017), state policies frequently prioritize assimilation into the dominant language. Comparative studies of early bilingual education highlight how sociopolitical contexts—ranging from immigrant integration to the protection of indigenous languages—shape the design and outcomes of bilingual programs (García et al., 2017; Hornberger, 2008).

The literature demonstrates that parental and community engagement are decisive in shaping children’s language trajectories. Home language means any language(s) used in the household; it may include multiple languages. Home language practices, parental attitudes, and intergenerational transmission of cultural values strongly influence whether children sustain their heritage languages (De Houwer, 2021; King & Fogle, 2013). Narrative practices such as storytelling, family literacy activities, and shared media use are recognized as effective strategies for strengthening HL skills in early childhood (Anderson et al., 2016). Without such reinforcement, institutional programs alone often fall short of ensuring long-term heritage language maintenance.

Teacher training and agency constitute another critical dimension of early bilingual education. Studies show that educators’ professional knowledge, beliefs, and ability to adapt pedagogical practices play a central role in supporting bilingual development (Pérez-Milans, 2015; Menken & García, 2010; Tollefson, 2015). Teachers who can flexibly employ strategies such as translanguaging—allowing children to draw on their full linguistic repertoires—are better able to accommodate diverse linguistic backgrounds and foster inclusive learning environments (García & Wei, 2014). Conversely, insufficient preparation and lack of institutional support often undermine program effectiveness.

The present study builds on ecological perspectives in bilingual education, which stress the interdependence of home, school, and community in shaping children’s language learning opportunities (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). The concept of the “social environment” is here operationalized to encompass families, educators, institutions, and local communities as actors whose attitudes, resources, and practices influence the success of bilingual education reforms. This aligns with international scholarship demonstrating that effective bilingual education requires systemic support across multiple levels rather than being confined to classroom instruction (Ricento, 2006; Spolsky, 2004).

Development of bilingual education programs can be fruitfully framed within an ecological model of language learning, which emphasizes the interplay between individual learners, families, institutions, and broader sociopolitical contexts (Schwartz, 2024). Within this framework, pedagogical innovation may take several directions. First, the incorporation of translanguaging practices allows learners to mobilize their full linguistic repertoires, supporting both cognitive development and identity formation (Cenoz & Gorter, 2021; Dikilitaş et al., 2023; Pontier & Gort, 2016). Second, the use of interactional analysis offers powerful tools for examining classroom discourse and identifying practices that enhance equitable participation (Anatoli, 2025). Third, drawing on research in family language policy, educators can provide structured guidance to parents, helping them establish home-based practices that reinforce heritage language use alongside majority language acquisition (Wright & Higgins, 2021). Finally, the integration of digital resources into bilingual education—ranging from online platforms to interactive storytelling apps—has been shown to extend language learning opportunities beyond the classroom and to foster multimodal forms of literacy (Li, 2024; Wells Rowe & Miller, 2016). Taken together, these perspectives highlight the need for an integrated, multi-level approach that situates bilingual education within changing social, familial, and technological ecosystems.

In this study, the “social environment” is conceptualized ecologically to encompass the family, community, and institutional contexts—including policy, educational structures, and cultural norms—that shape—and are shaped by—interactions around bilingual education. This aligns with Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory, which emphasizes that development results from reciprocal processes among nested environmental systems, ranging from immediate microsystems (e.g., family, school) to broader macrosystems (e.g., cultural and policy contexts) (EBSCO, 2025). By situating Georgia’s 2020 preschool bilingual education reform within this broader field, the present study contributes to understanding how sociopolitical reforms interact with parental attitudes, teacher agency, and institutional structures in ethnically diverse regions. While the global literature has examined similar dynamics in contexts as varied as Latin America, North America, and Northern Europe, relatively little is known about early bilingual education in the South Caucasus. This study thus extends the comparative evidence base by analyzing how the readiness of the social environment shapes the implementation of bilingual education in Georgia’s minority regions.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data Sources

This study combined multiple sources of data to enable a document and policy analysis of early education and preschool institutions in Georgia, with a particular focus on bilingual education in ethnically diverse regions. Statistical data on preschool enrollment in Kvemo Kartli and Samtskhe–Javakheti, disaggregated by municipality, were obtained from the Ministry of Education and Science, the Education Management Information System (EMIS), the National Statistics Office of Georgia, and the National Center for Educational Quality Enhancement (NCEQE). Population census data and region-specific statistics on kindergartens participating in the bilingual education pilot program were also consulted.

To contextualize these findings, international legal frameworks were reviewed, including the UN Declaration on the Rights of Persons Belonging to National or Ethnic, Religious and Linguistic Minorities (UN Declaration, 1992) and the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (Council of Europe, 1995). National legislation and policy documents were analyzed, such as the Law on Early and Preschool Upbringing and Education (2017), the Professional Standard for Early Childhood Teacher-Educators, and accompanying technical regulations. In addition, government and NGO reports were included, such as the 2023–2024 Report of the State Strategy for Civic Equality and Integration (2024), reports by the Public Defender’s Office (2020), UNICEF assessments (Andguladze et al., 2020), and the diagnostic study on early childhood education (Ministry of Education, Science and Youth of Georgia, 2017) commissioned by the government of Georgia (PPMI, 2022; Child Wellbeing in Georgia, 2023). Scholarly literature on the role of parents in early bilingual education was also reviewed (Možný, 1999; Berger, 2000; Fadlillah & Fauziah, 2022). The selected keywords included early education, positive parenting, parents’ role, bilingual education, situation of ethnic minorities, and status and rights of ethnic minorities. They informed the construction of the interview protocols, which were subsequently applied in the analysis of the collected data.

4.2. Fieldwork and Study Sites

Fieldwork was conducted in two regions of Georgia with significant ethnic minority populations: Kvemo Kartli and Samtskhe–Javakheti. Five preschool institutions piloting the bilingual education program were selected as study sites. In Kvemo Kartli, the sites included preschools in Algeti and Sadakhlo (Marneuli Municipality). In Samtskhe–Javakheti, institutions in Akhalkalaki, Ninotsminda, and the village of Gandza were chosen.

4.3. Participants

This study targeted a wide range of stakeholders involved in the design, implementation, and reception of the bilingual education program.

Institutional and policy-level stakeholders included the following:

- (a)

- Officials of the Ministry of Education and Science responsible for program oversight (two in-depth interviews);

- (b)

- Leaders of municipal departments of early care and learning (two in-depth interviews);

- (c)

- Kindergarten directors (three interviews) and methodologists, i.e., professionals overseeing the pedagogical processes in kindergartens (two interviews).

Thirteen focus group discussions were conducted across three municipalities, involving a total of 157 participants. In each kindergarten, one focus group was held with parents or guardians of children enrolled in the program and another with early childhood educators. Additionally, in each municipality, one focus group was organized with specially trained bilingual teachers. All available participants were invited to take part. The sampling was inclusive and voluntary.

All the participants in the project were informed about the goals of the research and gave written consent for their words to be quoted. The interviewees and focus group participants were anonymized.

4.4. Instruments and Data Collection

Semi-structured questionnaires were developed for different respondent groups (Appendix A, Appendix B and Appendix C). The decision-maker questionnaire focused on program design, effectiveness, and institutional collaboration. The educator questionnaire elicited teachers’ experiences with bilingual practices and collaboration with families. The parent questionnaire explored family language practices, attitudes toward bilingualism, and perceptions of program outcomes. Interviews and focus groups followed a structured protocol and were designed to capture both educational practices and broader dimensions of social and cultural integration. The principle of data saturation was applied (Saunders et al., 2018), with data collection continuing until no new themes emerged.

4.5. Data Analysis

Data were analyzed using a hybrid methodological approach, combining elements of systematic and narrative review (Turnbull et al., 2023) with empirical qualitative analysis (content and thematic analyses, e.g., Güler & Taş, 2020; Oldham & McLoughlin, 2025). Primary data (interviews and focus groups) were transcribed and coded using MAXQDA. A qualitative content analysis approach was employed (Mayring, 2000), combining deductive categories based on the conceptual framework (e.g., preschool education, bilingual program, parental role, community attitudes) with inductive codes derived from participant responses. Coding reliability was ensured through (1) external peer review of the coding scheme and (2) re-coding by the author after a three- to four-week interval (Mayring, 2022).

The analysis was further supported by MAXQDA tools (Crosstab, Code Relation Browser, MAXMaps). For data visualization and exploration of intersections between categories, the networkD3 package in R/RStudio was applied. Findings were interpreted within the framework of the Total Quality Framework (TQF) (Roller, 2020), which integrates data collection, analysis, presentation, and interpretation. All materials are available in Georgian only.

The measurement focus is on perceptions of effectiveness, descriptions of practices, and documented procedures. Evidence comes from policy texts, administrative records, and stakeholder narratives; we do not claim standardized learning outcomes.

5. Results

5.1. Quantitative Analysis of the Interviews and Focus Group Discussions

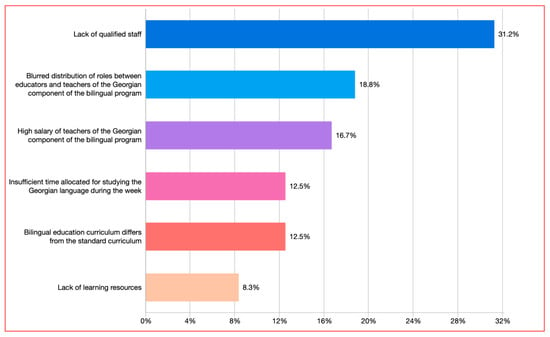

The primary challenges associated with bilingual education in the kindergartens selected for research are multifaceted and include the following (see Figure 1). The distribution points to implementation frictions rather than gaps in formal policy. Items such as “blurred distribution of roles” and “bilingual education curriculum differs from the standard curriculum” suggest that policy intent has not been fully operationalized into clear role definitions, guidance, and compatible curricular frameworks at the preschool level. The leading challenge—lack of qualified staff—is the primary capacity bottleneck. It is compounded by role ambiguity, uneven remuneration structures, and resource constraints. Together, these indicate weaknesses in recruitment, training, role design, and provisioning that directly affect delivery quality. None of the top items explicitly references parents or community; this implies that the most acute problems identified by institutions are internal (staffing, curriculum, time, resources). However, insufficient instructional time may also reflect scheduling pressures shaped by local expectations and collaboration patterns with families. Insufficient weekly time for Georgian and lack of resources likely limit children’s exposure and practice opportunities, which stakeholders elsewhere in this study linked to participation rather than measurable proficiency gains.

Figure 1.

Challenges related to bilingual education in the kindergartens researched.

With 31.2% citing a lack of qualified staff and 18.8% reporting blurred roles, capacity building should prioritize (a) clear job descriptions distinguishing early childhood educators and Georgian component teachers, (b) targeted pre-/in-service training in preschool second-language pedagogy, and (c) mentoring for bilingual assistants. The “high salary of teachers of the Georgian component” (16.7%) appears as a perceived inequity that can undermine team cohesion and retention of other staff. Harmonizing pay scales or introducing transparent role-based differentials with clear advancement pathways may mitigate friction. The 12.5% indicating insufficient weekly time suggests schools need minimum time allocations for the Georgian component, integrated into daily routines (circle time, play-based centers) to increase exposure without displacing core ECE activities. Differences between the bilingual and standard curricula (12.5%) call for crosswalks, pacing guides, and exemplar lesson sequences to ensure the bilingual strand is developmentally appropriate and coherent with national ECE standards. Although “lack of teaching resources” is the least-cited issue (8.3%), it constrains quality. A centralized repository of age-appropriate Georgian L2 materials, bilingual storybooks, and play-based tasks—paired with teacher guides—would support consistency.

5.2. Alignment of National Legal and Strategic Frameworks with Local Implementation

The social environment of bilingual preschool education encompasses not only families and educators but also the interaction between national policy and municipal governance. The findings reveal that although Georgia’s legal and strategic frameworks provide a foundation for bilingual education, their implementation at the local level remains inconsistent and poorly coordinated.

An official of the ministry (N.G.) acknowledged, “At the start of the program our communication with the mayors was bad and hampered proper working process. Now, after we have worked individually with the heads of the departments of early care and learning [explaining the goals of the program], they understand [what is required of them]. They do not create obstacles in anything, but it would not be true to say that they help us a lot.”

Methodologists at municipal departments of early care and learning were described as indifferent: “Since methodologists in the municipalities do not really care, we in the Ministry have to involve staff from local resource centers, and this works out more or less successfully.” (T.J.).

After a difficult period of trial-and-error and adjustment to the new situation, the heads of the municipal departments of early care and learning seem to be satisfied with the cooperation with the ministry. Despite these shortcomings, some municipal heads later reported positive collaboration: “We are constantly in touch with the Ministry, i.e., our methodologist collaborates with them.” (Z.K.); “It was a good idea [to collaborate], the program runs really well now.” (A.M.). These accounts illustrate that the social environment of bilingual education is weakened by institutional misalignment but can be strengthened through sustained dialogue between national and local actors.

5.3. Administrative Procedures, Staffing Models, Training, and Monitoring

Another critical dimension of the social environment is the administrative and institutional capacity to deliver bilingual education. Here, the data reveal a combination of insufficient preparation, staffing tensions, and uneven professional standards. Kindergarten associations reported they were not consulted in advance: “Yes, we received a letter asking if we would agree to participate in the program of bilingual teaching. After that, they had no contact with us.” (Head of the Kindergarten Association—A.M.); “I heard all this when they announced it to teachers… Later, when the ministry had difficulty with administrative management and needed help, there was an online meeting and at that meeting they told me that as the head of the association I should be in charge, but what exactly I should do and control, I don’t really know.” (Head of the Kindergarten Association—A.A.).

As one ministry official explained: “This is a very difficult process. Suddenly you enter kindergartens, you try to introduce bilingual education, but the parents look at you very skeptically. In fact, not only the parents, but also kindergarten employees, and the municipality—they simply don’t understand what you actually want.” (N.G.).

Concerns were also raised about instructional time: “My recommendation is to increase the time allocated for Georgian language learning.” (K.M., Ninotsminda); “Classes two days a week is too little for children. If you could inform the Ministry and recommend an ease in teaching hours, it would be great.” (A.A., Akhalkalaki).

Tensions also arose around staffing and salaries: “From what I understand, they have high salaries because they were trained [to teach Georgian in bilingual classes], they passed some exams and now they look down on our teachers... Our teachers were very upset at first, but now they have calmed down.” (Kindergarten manager—T.J.); “These girls, teachers of Georgian, you know, they worked just two days a week and earned 900 GEL [GEL is the currency code of Georgian money known as “lari”] a week, while our teacher, who works every single day, his salary is only 500 GEL. I think this is unfair.” (Kindergarten manager—A.A.).

Qualifications also varied significantly: “I have nothing against these girls, but they sent us a weak teacher, my teacher knows more.” (Kindergarten manager—A.M.); “The trouble is that the training courses provided for them are in the remote mode and they cannot replace university education. Ultimately, all this is reflected in the quality of the program and the teachers’ relations with parents.” (Methodologist, Ninotsminda Kindergarten Agency).

These findings underscore that without sufficient staffing models and professional development, the broader social environment for bilingual learning is compromised.

5.4. Parental, Caregiver, and Community Perceptions and Collaboration

The family and community dimension of the social environment plays a decisive role in the reception and sustainability of bilingual programs. Parents and local staff conveyed a positive orientation toward the initiative, though their involvement was often mediated by inconsistent communication.

Educators highlighted parental acceptance: “Everyone is satisfied. I really haven’t met anyone disappointed who said, ‘Why did you have to do this or that?’ We really haven’t had complaints.” (Focus group with educators).

However, parents mostly learned about the program informally. A focus group revealed that 80% of parents were informed by teachers rather than official channels. Kindergarten managers contested this, insisting on active outreach: “Parents are really happy and are very well informed, because we have talked about it many times; we disseminated information through local media.” (Kindergarten Manager—I.K.)

Parents expressed both optimism and concern: “To be honest, the results are not very good, but I hope that they will be in 1–2 years.” (A.M.); “I want my child to be able to speak fluently when he finishes the kindergarten and goes to school. But I haven’t seen such results yet.” (A.M.); “So far, everything has been going well. The changes are excellent. Bilingual education is worth the effort.” (Z.K.).

Regional contrasts were also evident: in Ninotsminda and Akhalkalaki, parents were more critical and demanded higher standards, often raising issues of nutrition, while in Gandza and Marneuli, parents tended to be more accepting but less engaged.

5.5. Reported Changes in Children’s Participation, Exposure to Georgian, and School Readiness

The child-centered dimension of the social environment reflects how program implementation affects children’s daily participation and learning trajectories. Educators pointed to gradual but meaningful improvements: “Yes, if a child understands basic things and can explain them to you, that’s a big deal!” (G.I.).

Longer-term effects were also noted: “On the contrary, now the trend is in favor of Tbilisi. Our young people are going there now when they finish high school. In the past they couldn’t because they were not proficient in the Georgian language. Now they speak Georgian and are no longer afraid.” (Educator—S.B.).

Although uneven, these reports suggest that the program is beginning to enhance children’s readiness for primary education and expand their future educational opportunities.

5.6. Cross-Stakeholder and Regional Similarities and Differences

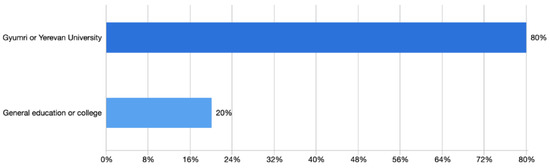

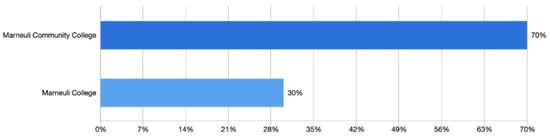

Taken together, the data demonstrate that across all stakeholder groups—ministry officials, municipal administrators, educators, and parents—communication gaps, staffing challenges, and insufficient Georgian-language hours are perceived as persistent barriers. However, stakeholder perspectives diverge in emphasis. Ministry officials stress structural challenges, while educators focus on classroom realities and fairness in staffing. Kindergarten managers defend municipal support, while teachers emphasize tensions with bilingual specialists. Parents, meanwhile, are generally positive but vary regionally: those in Ninotsminda and Akhalkalaki are more critical and demanding, whereas parents in Marneuli and Gandza are more accepting but less engaged. These findings confirm that the “social environment” of bilingual preschool education is multifaceted, requiring alignment across institutions, staff, families, and communities to ensure sustained success. The educational background of the educators is presented in Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Educational background of educators: Ninotsminda and Akhalkalaki.

Figure 3.

Educational background of educators: Marneuli.

The contrasts between stakeholder perspectives and regional contexts underscore the complexity of the social environment in which bilingual education unfolds. Interpreted through an ecological lens (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Schwartz, 2024), these findings highlight that language development cannot be explained solely by individual or classroom-level dynamics. Rather, it emerges from the interactions across multiple layers of the ecosystem—family practices and parental expectations, institutional structures and teacher preparation, and broader policy frameworks and state strategies. This multi-level perspective reveals how alignment, or misalignment, across these layers can either support or constrain the effectiveness of bilingual preschool education.

6. Discussion

The findings of this study can be understood within broader theoretical perspectives on bilingual education, particularly ecological models of language development (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Schwartz, 2024), family language policy (King et al., 2008; Wright & Higgins, 2021), and translanguaging practices (García & Wei, 2014; Dikilitaş et al., 2023). These frameworks allow us to situate the challenges and successes of the Georgian bilingual preschool initiative within international scholarship on early bilingual education. Importantly, the contrasts between stakeholder perspectives and between regions reveal the complexity of the social environment in which bilingual education unfolds (Tian & Huber, 2020). In line with ecological theory, the results demonstrate that language development cannot be reduced to individual or classroom-level factors but must instead be understood as the outcome of interactions across family, institutional, and policy layers.

The misalignment between national legislation and municipal practice illustrates the tension between macro-level policy design and meso-level implementation. Within the ecological model, this gap underscores the importance of institutional mediation between central frameworks and local practice. The observed lack of coordination between the Ministry of Education and municipal governments reflects a broader systemic weakness: interviews and focus groups reveal a lack of proactive engagement, unclear distribution of responsibilities, and insufficient preparatory work before the program was launched. Local authorities and educators were not adequately informed about the program’s goals or their expected roles, which led to confusion, inconsistent assessments of outcomes, and weak collaboration. Similar challenges of policy–practice alignment have been documented in other contexts (Turnbull et al., 2023), highlighting the need for stronger multi-level governance and sustained communication.

Staffing, training, and monitoring emerged as critical factors shaping the quality of children’s learning environments. While translanguaging research underscores the importance of teacher collaboration and professional development for creating flexible language practices (Pontier & Gort, 2016), in Georgia, these efforts are undermined by uneven teacher qualifications, limited training opportunities, and salary disparities between ministry-appointed bilingual teachers and local educators. These inequalities fuel tensions and undermine trust, even though they have not escalated into open conflict. Human resource challenges are particularly acute: demand for Georgian-speaking professionals is rising, yet only seven percent of surveyed bilingual teachers hold formal pedagogical degrees. Short-term training cannot replace university-level preparation, and this shortfall negatively affects instructional quality and parental confidence.

Despite these systemic shortcomings, parents and communities demonstrate largely positive attitudes toward the bilingual program. Many parents view Georgian language acquisition as essential for their children’s integration into Georgian society and future socio-economic mobility. However, communication remains problematic: most parents first learned about the program through informal conversations with teachers rather than through official channels. This lack of structured dissemination contributes to inflated expectations and occasional misunderstandings. Parental support, nevertheless, affirms the significance of family language policy and community involvement (Fadlillah & Fauziah, 2022; King & Fogle, 2013). Yet, levels of engagement vary across regions: in Samtskhe–Javakheti, parents are more educated, more critical, and hold higher expectations; in Kvemo Kartli, parental involvement is lower, and concerns are more often directed at issues such as nutrition rather than pedagogy.

The gradual improvement in children’s exposure to Georgian and their readiness for school reflects the micro-level impact of the reform within the ecological model. Educators report greater confidence among children and a growing tendency for young people to pursue education in Tbilisi rather than abroad—an indicator of shifting linguistic motivation. These findings resonate with international evidence that early bilingual education supports not only language proficiency but also long-term academic achievement (Cummins, 2000; De Houwer, 2021). At the same time, progress is hindered by insufficient instructional time in Georgian, which many educators identify as a major obstacle to achieving program goals.

Overall, the Georgian bilingual preschool initiative is still in its infancy. The findings highlight both its potential and the obstacles that must be addressed for the program to succeed. Systemic weaknesses include poor coordination between national and municipal levels, unclear communication with educators and parents, inadequate preparatory work, and a lack of professional standards for bilingual teachers. At the same time, community goodwill, parental support, and the openness of educators create a foundation for improvement. Drawing on international models, the program could be strengthened by clearer job descriptions, standardized competencies, sustained professional development, and systematic workshops for educators. Methodologists, administrators, and advisors should also learn from countries with established bilingual systems. Addressing these issues will require better alignment between national, municipal, and institutional stakeholders to ensure that the program meets its long-term objectives of promoting both minority language preservation and state-language acquisition.

Taken together, these findings affirm the value of an ecological perspective for understanding bilingual education reform in Georgia. At the macro level, national policies establish ambitious frameworks, but without sufficient mediation at the meso level of municipalities and preschool institutions, their implementation remains inconsistent. At the micro level, the everyday interactions of children, parents, and educators reveal both the promise and fragility of the reform. This layered interplay underscores that the success of bilingual education depends not only on the design of language policies but also on the dynamic interconnections between families, communities, educators, and institutions that shape children’s opportunities to thrive.

This study’s contributions lie in offering a multi-level, qualitative picture that links national policy intent to on-the-ground delivery in two minority-dense regions, highlighting specific points where implementation falters and where it can be strengthened. Limitations include the geographically bounded sample, reliance on stakeholder self-reports, and the absence of standardized child language measures. Consequently, findings should be interpreted as indicative of processes and conditions rather than causal effects on proficiency.

7. Conclusions

This study demonstrates that Georgia’s preschool bilingual education pilot rests on solid legal and strategic foundations, yet its implementation encounters persistent challenges at municipal and institutional levels. The clearest facilitators of success are stable staffing models, the presence of trained bilingual assistants, structured professional development for early childhood educators in second-language methodologies, and sustained two-way engagement with parents. Where these conditions are present, stakeholders report more consistent exposure to Georgian and greater participation by minority children. This study contributes a multi-level qualitative account that links national policy intent with on-the-ground delivery in two minority-dense regions, pinpointing where the process falters and where it may be strengthened. At the same time, its geographically bounded sample, reliance on stakeholder self-reports, and the absence of standardized measures of child language outcomes indicate that findings should be interpreted as indicative of processes rather than causal effects on proficiency.

The analysis further highlights the crucial role of parents, educators, and local communities in shaping the trajectory of the reform. Parental attitudes are generally positive, although they remain tempered by limited information about the program’s goals and structure. Education levels and parental motivation emerge as strong predictors of children’s academic outcomes, most evident in regions such as Akhalkalaki and Ninotsminda, where parents display both critical scrutiny and creative engagement with the initiative. Concerns about teacher qualifications are widespread, with parents stressing the need for educators formally trained in language pedagogy. Respondents also underscored the lack of preparatory consultation with local communities before the program’s launch, a gap that continues to undermine trust and transparency. Parents and educators expressed dissatisfaction with the limited involvement of preschool management, perceiving it as detrimental to the program’s effectiveness. Finally, tensions between local educators and ministry-trained bilingual teachers underscore socio-economic inequalities, particularly salary disparities that appear unjust given the higher qualifications of many local staff. These dynamics point to the need for stronger communication, more equitable professional standards, and closer alignment between central authorities, municipalities, and preschool institutions if Georgia’s bilingual education initiative is to achieve its long-term objectives.

Future work should pair qualitative monitoring with developmental benchmarks and classroom observation rubrics, expand to additional municipalities, and pilot low-cost tools for tracking children’s language participation and exposure over time. Within Georgia’s broader commitment to minority rights and inclusion, strengthening institutional capacity and parent–school collaboration in preschool settings appears essential to realizing the promise of bilingual education.

In the future, studies should also prioritize the inclusion of children’s perspectives, using age-appropriate methods such as observation, interviews, or language tasks to better understand how the children experience bilingual education. Similarly, the role of teacher training deserves further attention. Research should explore the effectiveness of current training models and assess the need for formal bilingual teacher education tracks at Georgian universities. Another promising area for exploration is the relationship between community involvement and program success. Understanding how parental attitudes, family language policies, communication strategies, and local trust-building efforts influence outcomes could help design more responsive and inclusive educational policies. The further development of bilingual education methods, including translanguaging, will also be beneficial.

Comparative studies across different regions and ethnic groups would also help to identify context-specific challenges and successful practices. Lastly, more detailed analyses of institutional coordination and governance—particularly between the Ministry of Education and municipal structures—would be valuable for improving policy coherence and implementation effectiveness. While this study sheds light on the current state of bilingual education in Georgia, it also highlights the need for deeper, broader, and more inclusive research to support its long-term success and refinement.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The research permission was received from the Akaki Tsereteli State University (official address: Tamar Mepe Street 59, Kutaisi 4600, Georgia) on 21 June 2023, registration number MES 9 230000732223.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed written consent was obtained from all participants in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Available with restrictions upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Questionnaire for Decision-Makers

The questionnaire is designed to study the perspectives of decision-makers involved in the implementation of the ongoing pilot program for early bilingual education. The aim is to analyze methodological approaches introduced to parents and the community within the framework of this project.

Objective: To analyze the methodological approaches introduced to parents and the community in the context of the ongoing pilot program for early bilingual education.

Respondents:

- Representatives from the Ministry of Education and Science (3 individuals);

- Directors of kindergarten associations (2 individuals).

Instructions: In-depth interviews will be conducted with respondents. Personal data (name, surname, position) will not be included in the final analysis of the dissertation.

Questions:

1. Name and surname

2. Position

3. Job responsibilities

4. Involvement with the early bilingual program

5. What age group of children is involved in the bilingual program?

6. Evaluate the challenges of the ongoing bilingual program at the preschool level (strengths and weaknesses).

7. Does the current self-assessment process of kindergartens include the evaluation of the component of working with parents?

8. Does the current self-assessment process of kindergartens include the evaluation of the component of community interaction/collaboration?

9. Are approaches tailored to national minorities considered in the component of working with parents?

10. How does the “Law on Early and Preschool Education” and the “State Standard for Early and Preschool Education” define the planning and monitoring of the component of working with parents and the community?

11. Share what you know about strategies developed by other countries for working with parents and the community.

12. Was the experience of any country shared in planning the early bilingual program for working with parents and the community? Which country specifically? What type of experience is discussed?

13. In your opinion, what specific activities should be planned in preschool institutions to actively involve parents in the bilingual program?

14. Are specialists in early education and quality assurance, as well as curriculum experts, selected to evaluate work with parents and the community in kindergartens within their competencies? If yes, what tool will be used? How will the evaluation be conducted?

15. The ministry has officially announced plans for a continuous cycle of training for educators in preschool institutions. Is there any type of training developed for working with parents and the community? Does the respondent know when the training will be conducted?

Appendix B. Questionnaire for Educators

The questionnaire is designed to study the attitudes and perceptions of educators involved in the ongoing pilot project of early bilingual education in preschool institutions. The aim is to analyze methodological approaches introduced to parents and the community within the framework of this project.

Objective: To analyze the methodological approaches introduced to parents and the community in the context of the ongoing pilot project for early bilingual education.

Respondents: Educators from preschool institutions involved in the pilot program for early bilingual education.

Instructions: A focus group is planned with respondents. Personal information (name and surname) will not be included in the final analysis of the dissertation. Information obtained from the research, such as age, education, ethnicity, gender, residence, and region, will be generalized for analysis and reflected in the dissertation. Selection of participants for focus groups will be based on linguistic competence assigned within the program, distinguishing between first language (native) and second language (state) teachers.

Questions for the Pedagogical Staff

1. Name and surname

2. Education

3. Place of residence

4. Which regulatory documents on preschool education are you familiar with?

5. Have you heard about the ongoing self-assessment process? What do you know specifically?

6. What does the legislation foresee regarding work with parents and the community?

7. Describe the relationship between first language and second language teachers (personal level, cooperation quality).

8. What approaches and strategies do preschool educators use in the bilingual education process (language alternation, children’s competencies in native and target languages)?

9. What challenges do you face when working with parents and the community?

10. Is the implementation of the early bilingual education program effective?

11. Does the early bilingual education program improve children’s language competencies?

12. How do you assess the role of parents in the program implementation process?

13. Are specific activities planned to involve parents in the process? What do you know about this?

14. Educators’ findings and advice to decision-makers for implementing early bilingual education.

Appendix C. Questionnaire for Parents

The questionnaire is designed to study the attitudes and perceptions of parents involved in the ongoing pilot project of early bilingual education. The aim is to analyze methodological approaches introduced to parents and the community within the framework of this project.

Objective: To analyze the methodological approaches introduced to parents and the community in the context of the ongoing pilot project for early bilingual education.

Respondents: Parents of children involved in the pilot program for early bilingual education.

Instructions: A focus group is planned with respondents. Personal information (name and surname) will not be included in the final analysis of the dissertation. Information obtained from the research, such as age, education, employment, ethnicity, gender, residence, and region, will be generalized for analysis and reflected in the dissertation. This study will explore the perspectives of two categories of parents: those whose children are involved in bilingual education and those who have not yet decided.

Questions:

1. Name and surname

2. Age

3. Gender

4. Education

5. Employment

6. Place of residence

7. What do you know about the pilot program for early bilingual education?

8. Is your child involved in the pilot program for early bilingual education? If yes, what are your expectations?

9. Based on your experience, do you consider the wide implementation of bilingual education programs as a method to be appropriate? Why?

10. What activities are planned in the kindergarten to involve parents? What have you heard about the planned activities?

11. In which activities planned by the preschool institution have you participated?

12. Describe your child’s attitude towards the teacher of their first language (native language).

13. Describe your child’s attitude towards the teacher of the second language (state language) which is of a different language/culture.

14. What has your child learned about Georgian culture through the program? Has their knowledge increased?

15. Has your child learned the state language? Over what period?

16. Have your expectations about the program been met?

17. Does your child know about Azerbaijani culture? How is this culture introduced at home and in the kindergarten?

18. What do parents themselves say about Georgian culture?

19. What challenges do parents face in interacting with preschool institutions? How do they cope with these challenges?

20. Parents’ wishes and advice to the program implementers.

References

- Anatoli, O. (2025). Multimodality, embodiment, and language learning in bilingual early childhood education: Enskilment practices in a Swedish–English preschool. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 50, 100879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, J., Anderson, A., & Sadiq, A. (2016). Family literacy programmes and young children’s language and literacy development: Paying attention to families’ home language. Early Child Development and Care, 187(3–4), 644–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andguladze, N., Gagoshidze, T., & Kutaladze, I. (2020). Education policy and research association: Early childhood development and education in georgia. UNICEF. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/georgia/media/5796/file/Early_Development_Report_EN.pdf (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Berger, E. (2000). Family involvement: Essential for a child’s development. In E. H. Berger (Ed.), Parents as partners in education. Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Bialystok, E. (2017). The bilingual adaptation: How minds accommodate experience. Psychological Bulletin, 143(3), 233–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cenoz, J., & Gorter, D. (2021). Pedagogical translanguaging. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chachanidze, I., & Guchua, T. (2024). Russification of language and culture in Soviet Georgia (according to the Georgian émigré press). International Journal of Multilingual Education, 25(1), 81–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Child Wellbeing in Georgia. (2023). Results of the child welfare survey (CWS) conducted by the national statistics office of Georgia (Geostat), with support from UNICEF. Available online: https://www.geostat.ge/media/52968/Child-Welfare-Survey-%28CWS%29.pdf (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Council of Europe. (1995). Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities (CAHMIN). Available online: https://rm.coe.int/16800c10cf (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Cummins, J. (2000). Language, power, and pedagogy: Bilingual children in the crossfire. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- De Houwer, A. (2021). Bilingual development in childhood. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dikilitaş, K., Bahrami, V., & Erbakan, N. T. (2023). Bilingual education teachers and learners in a preschool context: Instructional and interactional translanguaging spaces. Learning and Instruction, 86, 101754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EBSCO Research Starters. (2025). Social ecological model. EBSCO knowledge advantage. Available online: https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/environmental-sciences/social-ecological-model (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Fadlillah, M., & Fauziah, S. (2022). Analysis of Diana Baumrind’s parenting style on early childhood development. Al-Ishlah: Jurnal Pendidikan, 14(2), 2127–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabunia, K., Gochitashvili, K., & Shabashvili, G. (2022). Ways and needs of transition from monolingual to multilingual teaching model in the Georgian education system. Educational Role of Language Journal, 7(1), 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, O. (2009). Bilingual education in the 21st century: A global perspective. Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- García, O., Lin, A. M. Y., & May, S. (Eds.). (2017). Bilingual and multilingual education. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- García, O., & Wei, L. (2014). Translanguaging: Language, bilingualism and education. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Geostat. (2017). Population census 2014. Data in-depth analysis. Available online: https://www.geostat.ge/en/single-news/1022/population-census-2014-data-in-depth-analysis (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Gorgadze, N. (2016). Rethinking integration policy–Dual ethnic and cultural Identity. International Journal of Multilingual Education, 1(8), 6–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güler, H., & Taş, E. (2020). Thematic content analysis for pre-school science education research areas in Turkey. Journal of Computer and Education Research, 8(15), 323–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornberger, N. H. (Ed.). (2003). Continua of biliteracy: An ecological framework for educational policy, research, and practice in multilingual settings. Multilingual Matters. [Google Scholar]

- Hornberger, N. H. (Ed.). (2008). Can schools save indigenous languages? Policy and practice on four continents. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Isakadze, A. (2023). Guarantees of the right to education of ethnic minorities and best approaches to its protection. Available online: https://socialjustice.org.ge/ka/products/etnikuri-umtsiresobebis-ganatlebis-uflebis-garantiebi-da-misi-datsvissauketeso-midgomebi (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Kevlishvili, E., Alexandria, N., & Mushkudiani, N. (2005). General overview of international organizations and their cooperation with Georgia. Available online: https://www.nplg.gov.ge/greenstone3/halftone-library/collection/civil2/document/HASH018eb24b8c617aa8226a299c;jsessionid=702A134F7A66DFFC96B2200072470FAB?ed=1b (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- King, K. A., & Fogle, L. (2013). Family language policy and bilingual parenting. Language Teaching, 46(2), 172–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, K. A., Fogle, L., & Logan-Terry, A. (2008). Family language policy. Language and Linguistics Compass, 2(5), 907–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kymlicka, W. (2007). Multicultural odysseys: Navigating the new international politics of diversity. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Law on Early and Preschool Upbringing and Education. (2017). Available online: https://sansad.in/getFile/BillsTexts/RSBillTexts/Asintroduced/playschl-E-151217.pdf?source=legislation (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Li, Y. (2024, July 12). Technological advances in early childhood bilingual learning: A quantitative analysis. 5th International Conference on Education Innovation and Philosophical Inquiries (pp. 14–20), Huntsville, AL, USA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- May, S. (Ed.). (2013). The multilingual turn: Implications for SLA, TESOL, and bilingual education. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring, P. (2000). Qualitative content analysis. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 1(2), 20. [Google Scholar]

- Mayring, P. (2022). Qualitative content analysis: A step-by-step guide. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Menken, K., & García, O. (Eds.). (2010). Negotiating language policies in schools: Educators as policymakers. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Migration Policy Hub. (2011). Migration policy index. Available online: https://migrationresearch.com/item/multicultural-policy-index/474317# (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Ministry of Education, Science and Youth of Georgia. (2017). Early and preschool state standards of education. Available online: https://mes.gov.ge/content.php?id=7761&lang=eng (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Misachi, J. (2017). What Languages are spoken in Georgia? Available online: https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/what-languages-are-spoken-in-georgia.html#:~:text=There%20are%20approximately%2014%20languages%20spoken%20in%20Georgia,is%20the%20official%20and%20primary%20language%20of%20Georgia (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Možný, I. (1999). Sociology of family. SLON. [Google Scholar]

- Oldham, P., & McLoughlin, S. (2025). Character education empirical research: A thematic review and comparative content analysis. Journal of Moral Education. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Milans, M. (2015). Language education policy in late modernity: (Socio)linguistic ethnographies in the European Union. Language Policy, 14(2), 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, A. (2005). The framework convention for the protection of national minorities and the protection of the economic rights of minorities. European Yearbook of Minority Issues, 3, 287–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontier, R., & Gort, M. (2016). Coordinated translanguaging pedagogy as distributed cognition: A case study of two dual language bilingual education preschool coteachers’ languaging practices during shared book readings. International Multilingual Research Journal, 10(2), 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PPMI. (2022). Diagnostic study of early childhood education (ECE) in Georgia. Available online: http://iiq.gov.ge/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Diagnostic-Study-of-Early-Childhood-Education-ECE-in-Georgia.pdf (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Public Defender’s Office. (2020). Results of the monitoring of preschool and educational institutions conducted by the public defender’s office. Available online: https://ombudsman.ge/eng/190307051819angarishebi/special-report-on-monitoring-of-preschool-institutions (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Report of the State Strategy for Civic Equality and Integration. (2024). Decree №356 of the government of Georgia July 13, 2021 Tbilisi. Available online: https://smr.gov.ge/uploads/Files/_%E1%83%98%E1%83%9C%E1%83%A2%E1%83%94%E1%83%92%E1%83%A0%E1%83%90%E1%83%AA%E1%83%98%E1%83%90/Concept_ENG21.12.pdf (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Ricento, T. (2006). An introduction to language policy: Theory and method. Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Roller, M. R. (2020). The in-depth interview method: 12 articles on design and implementation. Available online: https://rollerresearch.com/MRR%20WORKING%20PAPERS/IDI%20Text%20April%202020.pdf (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Saunders, S., Sim, J., Kingstone, T., Baker, S., Waterfield, J., Bartlam, B., Burroughs, H., & Jinks, C. (2018). Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality & Quantity, 52(4), 1893–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, M. (2024). Ecological perspectives in early language education: Parent, teacher, peer and child agency in interaction. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Spolsky, B. (2004). Language policy: Key topics in sociolinguistics. Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tabatadze, S. (2021). Reconsidering monolingual strategies of bilingual education through translanguaging and plurilingual educational approaches. Are we moving back or forward? International Journal of Multilingual Education, 17, 48–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The MCP index project. (2025). Available online: https://www.queensu.ca/mcp/about (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Tian, M., & Huber, S. G. (2020). Mapping educational leadership, administration and management research 2007–2016: Thematic strands and the changing landscape. Journal of Educational Administration, 58(2), 129–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tollefson, J. W. (2015). Language education policy in late modernity: Insights from situated approaches—Commentary. Language Policy, 14(2), 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turnbull, D., Chugh, R., & Luck, J. (2023). Systematic-narrative hybrid literature review: A strategy for integrating a concise methodology into a manuscript. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 7(1), 100381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Declaration. (1992). Declaration on the rights of persons belonging to national or ethnic, religious and linguistic minorities. 18 December’ general assembly resolution 47/135. Available online: https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/declaration-rights-persons-belonging-national-or-ethnic (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- UNESCO. (2019). Right to Education Handbook. Available online: https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000366556 (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Wells Rowe, D., & Miller, M. E. (2016). Designing for diverse classrooms: Using iPads and digital cameras to compose eBooks with emergent bilingual/biliterate four-year-olds. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 16(4), 425–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, L., & Higgins, C. (Eds.). (2021). Diversifying family language policy. Bloomsbury Academic. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).