1. Introduction

This research is part of the contemporary debate on digital accessibility, bilingual education, and teacher training, offering insights for the formulation of institutional policies and pedagogical strategies that recognise deafness not as a disability, but as a difference that requires specific approaches based on equity, respect for linguistic identity, and the effective participation of deaf individuals in educational processes.

The purpose of this study is to analyse the process of creating and making accessible digital teaching materials available in undergraduate courses offered by a Brazilian public university. The research covers both face-to-face courses, such as LIBRAS Language and Literature, and distance learning programmes offered by the Open University of Brazil (UAB).

The research is based on the recognition that the educational inclusion of deaf students in higher education is not limited to physical or virtual presence, but depends on effective linguistic, communicational and cultural participation in the teaching-learning process.

According to the

IBGE (

2021), Brazil has a population of over 213 million inhabitants distributed across a land area of 8,510,345 km

2, divided into five regions with specific characteristics that influence education at all levels. In this context, face-to-face teaching alone does not meet the demand for higher education, which has led to the adoption of strategies to expand access, particularly in teacher training (

Senkevics, 2022). Between 1991 and 2020, enrolment increased significantly, driven by public policies targeting low-income students and historically excluded groups. In this scenario, the Open University System of Brazil (UAB), created in 2006, played a key role in strengthening internalisation and distance learning, with the objective of reducing regional inequalities and training teachers on a large scale.

With regard to distance learning (DL) and the inclusion of deaf people, we intuit that there is an additional complexity regarding the choices and use of inclusive teaching materials and other resources involved (communication, human, technological, physical infrastructure), whether in a normal context or in an emergency context, as was the case with the COVID-19 pandemic, which exacerbated pre-existing inequalities, exposing critical gaps in the preparation of teachers for inclusive online teaching.

In teacher training courses, these difficulties become even more critical, since any shortcomings compromise not only the individual learning of deaf students, but also the training of future educators in terms of their commitment to inclusion.

With regard to the challenges of including deaf students, although online education offers flexibility (geographical, schedule and location, autonomy and time management, reduced travel costs, among others), it often does not meet the specific needs of deaf students, given that deafness, due to its linguistic and cultural differences, requires a specific educational approach that goes beyond the simple adaptation of textual content, considering that it requires pedagogical and technological adaptations that are often absent in digital platforms.

Almeida (

2009) states that by associating assistive technologies with distance learning, it is possible to expand access and promote greater autonomy for people with disabilities, transforming virtual environments into more inclusive and democratic spaces. However, in distance learning or remote teaching, the predominance of text-based digital platforms, the scarcity of videos in LIBRAS, the limited training of teachers in the use of assistive technologies, and the absence of clear institutional guidelines on accessibility create barriers to the full participation of deaf students in academic life.

However, the effective inclusion of students with disabilities—particularly deaf students—continues to pose a substantial challenge, both in face-to-face courses and in programmes mediated by digital technologies. In this scenario, the production of inclusive teaching materials for people with hearing impairments stands out.

According to

Tavares and Höfling (

2024), the creation of accessible teaching materials for deaf students requires a thorough understanding of their linguistic, communicative, and cognitive needs. The production of teaching materials adapted to LIBRAS strengthens a truly inclusive and equitable education.

The materials must take into account the visual-spatial modality of LIBRAS, the linguistic differences in relation to spoken and written Portuguese, and the importance of visual resources such as sign language videos, qualified subtitles, graphic elements, and multimodal interaction, according to

R. M. d. Quadros (

2004).

Additionally, it is necessary to recognise that the production of these materials is not limited to a technical process, but involves pedagogical, epistemological, and cultural choices that require collaboration between teachers, interpreters, accessibility specialists, instructional designers, and deaf students themselves.

When it comes to the specific experiences and needs of deaf students, it can be inferred that they may have unique learning experiences influenced by factors such as linguistic identity (e.g., the use of sign language), access to appropriate educational resources, and engagement with the deaf community.

According to

Kermit and Holiman (

2018), deaf individuals represent a linguistic and cultural group that often relies on interpreters to facilitate communication between teachers and students in the classroom. However, effective communication depends on the collaboration and responsibility of both parties, and to this end, it is necessary to choose the educational model that best suits the teaching of deaf students.

Regarding innovative pedagogical approaches,

Araújo et al. (

2021) discuss various educational models, addressing the different roles that teachers play—Pedagogy, Andragogy, and Heutagogy.

Blaschke (

2012), when discussing heutagogical practice, emphasises self-determined learning and its application in lifelong learning. Heutagogy can be an effective approach for the deaf population, as it respects individual differences and accommodates diverse learning styles.

Among the innovations in inclusive pedagogy for the deaf, one proposal is translation into sign languages assisted by Artificial Intelligence (AI), using translators such as VLibras and Hand Talk. According to

Mello and Lodi (

2015), the application of these translators in the classroom remains sporadic and often misaligned with contextual needs and marked by inconsistencies and a lack of integration with pedagogical actions.

According to the Ministry of Management and Innovation in Public Services (

MCTI, 2021), the VLibras Suite enables deaf people to access multimedia content in their natural language of communication, thereby enhancing the accessibility of computers, mobile devices, and web pages. The application was developed by the Federal University of Paraíba (UFPB) through the Digital Video Applications Laboratory (LAVID), in partnership with the MGISP, the Secretariat of Digital Government (SGD), the Ministry of Human Rights and Citizenship (MDHC), and the National Secretariat for the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (SNDPD). As an open-source tool adopted by public institutions and universities, VLibras can be integrated with Brazilian government systems. Its target users include public and private institutions, government websites, educational platforms, and deaf individuals who use LIBRAS. However, the application has limitations in both functionality and accuracy, particularly when translating regional idiomatic expressions or technical terminology in fields such as health, education, or mathematics. Furthermore, VLibras translates exclusively from Brazilian Portuguese into LIBRAS and does not support reverse translation from LIBRAS into Portuguese.

According to

Startup Hand Talk (

2022), the Hand Talk application was created and is maintained by the Brazilian company Startup Hand Talk Tecnologia S.A. It functions both as a pocket dictionary and as a translator, supporting the learning and practice of LIBRAS (Brazilian Sign Language), ASL (American Sign Language), and BSL (British Sign Language). This translator can be employed as a teaching resource from primary to higher education and is also applicable in business and social contexts. The app is available for Android and iOS platforms and integrates with WhatsApp, expanding its potential for inclusion and accessibility. Nonetheless, like VLibras, it faces limitations in functionality and accuracy, especially when translating regional idiomatic expressions or specialized terminology in areas such as health, chemistry, or physics. In addition, Hand Talk only performs translation from Portuguese into LIBRAS, ASL, or BSL, sign languages that are mutually distinct and not interchangeable (

Lemaster & Monaghan, 2005, p. 145), and it does not support reverse translation from LIBRAS to Portuguese or from ASL/BSL into English.

In addition to VLibras and Hand Talk, other translators and related tools are also in use, such as the LIBRAS Online Dictionary and the Spreadthesign Dictionary, as well as systems currently under study or development, including SignSpeak and Glove-Based Systems. These initiatives employ artificial intelligence to facilitate communication between deaf and hearing individuals and to support the inclusion of teachers and students in the teaching and learning process for deaf people. They are highlighted here due to their public availability and/or their technological and scientific relevance in both educational and corporate contexts, nationally (Brazil) and internationally.

This means that communication occurs unilaterally, making it incomplete on occasions when communication from English to LIBRAS and vice versa is required. Therefore, it is necessary to be discerning about the characteristics of the teaching material or inclusive resource you intend to use, as well as whether you are qualified to select, produce and use it.

With regard to the selection of inclusive teaching materials and the use of assistive resources, it should be noted that, in addition to training, university teachers need the support of multidisciplinary teams and academic-administrative management to help them design and produce such materials for students with hearing impairments.

Undergraduate courses aimed at training primary school teachers are a requirement under Brazilian law, which states that teaching materials must be inclusive for students with hearing impairments, including Libras, in compliance with Law 9.394, Law 14.191 and Law 10.436, which deal with Brazilian Sign Language (LIBRAS) and bilingual education for the deaf.

LIBRAS, even though officially recognised by Law 10.436 in 2002 as a legal means of communication and expression for the deaf community, remains underutilised in traditional academic settings. Its presence in university curricula and, above all, in digital teaching materials used in virtual learning environments, remains incipient and often restricted to isolated or sporadic initiatives.

The LIBRAS approach in higher education is essential to promote the inclusion and accessibility of deaf students, in addition to expanding the critical and civic education of future professionals. According to

R. M. d. Quadros (

2004), it is essential that higher education institutions offer adequate training on LIBRAS, contributing to the elimination of communication barriers.

2. Brazilian Sign Language (LIBRAS) in Higher Education Practices

The development of accessible teaching materials is a fundamental component in ensuring the full participation of deaf students in higher education, particularly in teacher training programmes. These materials must go beyond content accessibility, meeting the specific linguistic and communicative needs of deaf individuals whose mother tongue (L1) is Brazilian Sign Language. According to

R. M. d. Quadros (

2004), LIBRAS has its own grammatical structure, distinct from the Portuguese language (spoken and written), evidencing its linguistic autonomy as the natural language of deaf communities in Brazil.

University professors, especially those without formal training in inclusive education or accessibility, often face significant challenges when developing such materials. The creation of inclusive educational resources requires pedagogical expertise combined with proficiency in assistive technologies, bilingual education methodologies, and intercultural communication.

As noted by

Ting-Toomey and Dorjee (

2015), inclusive teaching depends on the development of three essential competencies: attitudes, knowledge, and skills—elements that are often underdeveloped in traditional teacher training.

These challenges are exacerbated in distance learning contexts, where instructional content is typically text-based and lacks multimodal support. To ensure comprehension, materials must be made available in a variety of formats, including video resources accompanied by LIBRAS interpretation, texts written in simple language, and visual elements that complement the content.

These materials must also be adaptable for offline use: downloadable, printable, and accompanied by clear technical instructions. Although resources such as VLibras and Hand Talk offer potential for automatic translation, their practical application remains limited due to insufficient contextual adaptation and a lack of teacher training.

Furthermore, in today’s media-saturated environment, characterised by student engagement with platforms such as YouTube, Instagram, and TikTok, educational content must also be designed to be visually dynamic and pedagogically engaging for all students.

Barbosa et al. (

2017) argue that social media platforms, although originally intended for entertainment, can contribute to the development of multisemiotic literacy when intentionally integrated into teaching strategies.

Currently, some university courses still rely on outdated formats, such as static PDFs, which do not address the multimodal needs of deaf students and fail to ensure equal access for all learners. According to

Oliveira and Paulo (

2023, p. 7), the use of materials produced for distance learning courses is closely related to the interaction among the main actors: tutors, teachers, and students. The authors emphasise that, in organising a course, both the quality and frequency of pedagogical interactions must be taken into account, as well as the student’s role—whether positioned as a passive recipient or as an active builder of their own knowledge.

Regarding the creation and use of videos, it is necessary to pay attention to and adhere to regulatory standards. In Brazil, the standards of the Brazilian Association of Technical Standards (ABNT) are essential in the selection of resources for teaching practices, in order to ensure worry-free accommodations. Specific Brazilian Regulatory Standards (NBR), such as ABNT 15.290 (

ABNT, 2016) and ABNT 15.999 (

ABNT, 2008), guide the use of videos in academic courses, with an emphasis on communication in LIBRAS.

An example of the potential of AI in education is its application in adapting videos so that deaf people can understand them. This process involves resources such as accessible subtitling, sound description, and translation into sign language. AI tools, such as Natural Language Processing (NLP) and sound recognition algorithms, facilitate the automation of these subtitles.

According to

Aenor (

2012), subtitling for the deaf and hard of hearing (LSE) goes beyond the transcription of dialogue. It includes:

Description of non-verbal sounds: Indicating sounds relevant to the context, such as “[Door creaking]” or “[Siren sound in the background]”.

Timing and synchronisation: Ensuring that subtitles are aligned with visual and audio events in the video.

Despite the advantages of AI in education, its effective implementation requires adequate training of teachers and infrastructure that enables the creation and use of resources. Therefore, it is essential to structure the educational environment and adapt curricula to ensure that AI complements the role of the educator, promoting a collaborative approach. This collaboration can improve communication, encourage innovation, and promote both personal and professional development, leading to more creative solutions to educational challenges.

For

R. M. Quadros (

2010), the current scenario of cultural and technological development helps us understand the communication processes of deaf people in interaction through different modalities (signs and writing), with the support of digital technologies (DTs). The use of these technologies by university professors is interesting because it can make teaching materials accessible and suitable for both deaf and hearing students at the same time, regardless of whether the courses are offered in person or remotely.

The promotion of inclusion also depends on sustained professional development and institutional support.

Araújo et al. (

2021) emphasise that initial teacher training alone is insufficient to deal with the complexities of teaching deaf students, reinforcing the need for continuous and specialised training.

In addition, the production of inclusive materials should be a collaborative and interdisciplinary effort, involving educators, sign language interpreters, educational psychologists, instructional designers, and other professionals with experience in special education. Equally important is the inclusion of deaf students in the design process, ensuring that educational content reflects their linguistic and cultural experiences and directly responds to their learning needs.

This accessibility requirement should be explicitly stated in educational materials. Technical procedures, such as access, download, and printing, should also be addressed. According to

Freire (

1996), No one can walk without first learning how to walk; without first learning how to embark on a journey on foot; without first learning how to reimagine and refine the dream that sets us off on our travel.. (p. 155). Teaching materials must be inclusive for students with hearing impairments, in accordance with Brazilian legislation, Law 9.394, and subsequent amendments, such as Law 14.191 and Law 10.436, which deal with Brazilian Sign Language (LIBRAS) and bilingual education for the deaf.

3. LIBRAS: Incorporation into Teaching Processes

Although Brazilian Sign Language is officially recognised as the main language of the deaf community in Brazil, its effective incorporation into educational practice remains limited. Several structural barriers—such as a shortage of qualified personnel, the absence of institutional policies, and a lack of systemic planning—continue to hinder the integration of LIBRAS into higher education curricula

IPAESE (

2021). As a result, the use of LIBRAS is often restricted to specific contexts for the deaf, leaving educators and hearing students without the tools necessary for effective communication.

This linguistic disconnect represents a significant obstacle to inclusive education. Although some hearing students are interested in interacting with their deaf peers, their limited sign language proficiency often results in superficial or ineffective exchanges, according to

Lopes and Goettert (

2015), and

Amka and Mirnawati (

2020). Consequently, deaf students may experience social isolation and academic disengagement, resulting in high dropout rates and poor academic performance, according to

Maia (

2016). Although inclusive practices have advanced in early childhood education,

Jorge and Ferreira (

2007) point out that higher education institutions remain unprepared to accommodate linguistic diversity and cultural specificity.

Overcoming this gap requires the development of teaching materials that are linguistically accessible and culturally responsive. Such materials must be adapted to the visual-spatial modality of LIBRAS and incorporate elements of Deaf Culture to preserve semantic and pragmatic accuracy.

For example, the interpretation of metaphorical or abstract content often requires cultural adaptation to maintain the intended meaning (

C. S. Rodrigues & Valente, 2012). Written materials must also be structured with exceptional clarity, as they lack paralinguistic resources, such as facial expressions and body language, which aid comprehension in sign language.

The linguistic differences between Portuguese and LIBRAS further reinforce the need for a well-thought-out instructional design, considering that the avatar or written language will act in different contexts and as if they were human beings communicating in person.

Santos (

2015, p. 126) states that:

LIBRAS-Portuguese translators and interpreters constantly receive various requests to work in different contexts, such as: medical and hospital care and clinical care (expert reports, consultations, emergencies, psychological treatments and others); religious contexts (ecumenical services at graduations or other activities); legal contexts (meetings with prosecutors, advisors or lawyers); administrative contexts (meetings in pro-rectorates, rectorates, departments, among others) The implementation of the Libras-Portuguese translation and interpretation service… technical visits and others); conference contexts in different fields of knowledge; audiovisual translation contexts (subtitling, dubbing and others); artistic-cultural contexts (festivals, musicals, shows, theatre and others) or even contexts such as environmental emergencies (tragedies involving fires, floods, in support of government agencies such as civil defence and others).

Santos’ statements about LIBRAS translators and interpreters show how challenging it is to effectively incorporate them into educational practice, especially in the production and use of inclusive teaching materials for deaf people, because they will have to be adapted so that there are no failures in communication or in the understanding of the content made available to students in real time or made available in an online repository.

According to Santos, “[…] translating from LIBRAS to Portuguese is just one variable. However, there are others, such as contextualising the conversation, understanding grammatical structures, gender issues and various other differences.” […]. When translating sentences from Portuguese into Sign Language, which has no verb conjugation (verbs are always in the infinitive) and requires facial and/or body expression, specific strategies are needed for translating and adapting written content into LIBRAS.

Table 1, adapted from

Honora (

2017), describes the main structural distinctions between Portuguese and LIBRAS, highlighting the importance of these considerations in the development of educational resources.

Adapting written materials into LIBRAS is not merely a literal translation; it involves a process of linguistic and visual restructuring. Translators must consider verb tense, gender, sentence structure, and lexical complexity to ensure that the message is both accessible and natural for deaf audiences.

Integrating LIBRAS into teaching practices is not simply a matter of direct translation, but rather a complex pedagogical undertaking. It requires intentional curriculum planning, linguistic competence, and institutional commitment to accessibility. Effective inclusion is only possible through coordinated collaboration between teachers, sign language interpreters, instructional designers, and accessibility specialists.

Such efforts must be supported by systemic policies that recognise the unique linguistic rights of the deaf community and integrate LIBRAS as a legitimate means of instruction at all levels of higher education. Understanding the nuances of LIBRAS, including elements such as movements and facial expressions, is essential for effective communication with deaf people.

4. Methodology

By favouring a qualitative approach, the study seeks to understand the practices and perceptions of teachers, coordinators and deaf students regarding the educational resources used in their courses. Based on the analysis of the materials available in virtual learning environments and the feedback from the subjects involved, the aim is to contribute to the development of pedagogical proposals that value linguistic diversity and ensure equitable learning conditions. In addition, the study questions the limits and possibilities of digital technologies—including machine translation tools and LIBRAS support platforms—in the context of inclusive higher education.

4.1. Study Design

This study used a qualitative case study design to explore the accessibility and development of inclusive teaching materials for deaf students in higher education. The research was conducted at the Federal University of Alagoas (UFAL), Brazil, and focused on ten undergraduate courses offered in both face-to-face and distance learning modalities.

The methodology was based on authors such as

Gray (

2012), who emphasises the careful selection of research instruments and the management of collected data. The research was also guided by the ideas of

Minayo (

2009), who states that research connects theory with the practical realities of a specific context.

The sample included nine distance learning courses, namely, Social Sciences, Physics, Geography, Languages (Portuguese, English, Spanish), Mathematics, Pedagogy, and Chemistry, taught by the Open University of Brazil (UAB). In addition, the face-to-face course in Brazilian Sign Language (LIBRAS) was analysed, as it was not available in online format. All programmes were coordinated by UFAL faculty and designed to prepare future teachers for basic education.

Participants were selected by purposive sampling and included 12 teachers (deaf and hearing), 3 course coordinators, and 6 deaf students. All participants were affiliated with teacher training programmes. The study complied with Brazilian ethical standards for research involving human subjects, ensuring informed consent and confidentiality. To ensure anonymity, the following codes were used: ‘PS’ means ‘deaf teacher,’ ‘PO’ means ‘hearing teacher,’ AO means ‘deaf student,’ and “CC” means ‘course coordinator.’

4.2. Data Collection

Data were collected using three complementary methods:

Semi-structured interviews with teachers, coordinators, and deaf students explored participants’ perspectives on the use of inclusive teaching materials, institutional support, and barriers to accessibility.

Documentary analysis of 657 teaching materials available in UFAL’s Virtual Learning Environment (VLE), hosted on the Moodle platform. The materials were extracted from 20 subjects from various programmes, including Social Sciences, Physics, Geography, Languages, Mathematics, Education and Chemistry. According to the Quality Standards for Distance Higher Education (

BRASIL. MINISTÉRIO DA EDUCAÇÃO, 2007, p. 18), the criteria include “teaching materials (their scientific, cultural, ethical, aesthetic, didactic-pedagogical, and motivational aspects; their suitability for students and for information and communication technologies; their communicative capacity; etc.) as well as the actions of documentation and information centres (media libraries)”;

Review of institutional documents, including the Course Pedagogical Projects (PPCs) and the CIED/UFAL Teaching Guide (

Universidade Federal de Alagoas, 2020) developed during the COVID-19 pandemic, which provided contextual information on educational resources and guidelines for remote teaching.

To ensure a comprehensive understanding of educational practices, challenges, and inclusive resources available to deaf students, two instruments were employed:

- 1.

Structured questionnaire for teachers and coordinators

A structured questionnaire was administered to teachers and course coordinators involved in teacher training programmes at UFAL. The instrument consisted of multiple-choice and open-ended questions designed to assess

Academic training and experience in inclusive education;

Familiarity with Brazilian Sign Language (LIBRAS) and its use in teaching;

Strategies adopted for the inclusion of deaf students in their courses;

Availability and use of teaching materials adapted to the visual-linguistic needs of deaf students;

Experiences with accessibility in virtual learning environments (for UAB programmes);

Perceptions regarding institutional support offered for inclusive practices.

The questionnaire allowed for comparisons between teachers of face-to-face and distance education programmes, focusing on pedagogical planning and accessibility measures. The open-ended responses provided qualitative depth, revealing individual perceptions and challenges in implementing inclusive methodologies. For deaf teachers, the form was administered through interviews conducted in LIBRAS with the support of interpreters.

- 2.

Semi-structured interview for deaf students

Deaf students enrolled in the LIBRAS programme were interviewed individually using a semi-structured script. The protocol consisted of 16 open-ended questions organised into thematic blocks:

Communication experiences on campus and in administrative services;

Perceptions about the implementation and enforcement of the Brazilian Sign Language Law (Law 10.436/2002);

Reflections on bilingual education and inclusive school models;

Personal educational trajectories from early education to higher education;

Adaptation of the LIBRAS undergraduate course to the needs of deaf students;

Quality and accessibility of teaching materials and virtual learning environments (VLE);

Experiences with distance learning and attitudes towards the possibility of a LIBRAS course via UAB;

Knowledge and use of sign language translation technologies and platforms;

Suggestions and reflections on the production of inclusive teaching materials.

These interviews, conducted in LIBRAS with the support of interpreters, captured unique insights into the educational realities of deaf students, focusing on their linguistic, social, and institutional experiences.

The analytical framework was based on the Quality Benchmarks for Distance Higher Education published in 2007 (

Battini et al., 2016), which served as a reference for the evaluation of digital instructional content. A classification of the tools available in the VLE, such as forums, quizzes, glossaries, wikis and videos, was developed based on institutional documentation.

4.3. Data Analysis

To ensure greater rigour in content analysis, inter-coder reliability was considered throughout the process. The three researchers involved in categorisation held a joint meeting to align their understanding of the criteria established based on

Bardin’s (

2016) framework. Subsequently, part of the material was coded independently by two researchers, and any discrepancies were discussed collectively until a consensus was reached. This procedure allowed for standardisation in the application of categories and strengthened the interpretative consistency of the results.

The VLE teaching resources were categorised and quantified to assess the presence of inclusive features, such as videos with LIBRAS interpretation, synchronised subtitles in all videos, textual transcripts of audio and video, chat or forum tools enabling video-based interaction in LIBRAS, texts written in simple and clear language with short sentences to support inclusive interaction between students and teachers, texts produced in sign language, and the use of assistive technologies.

Data triangulation between interviews, VLE content, and institutional documents reinforced the validity of the results, allowing for cross-checking of patterns and gaps in the provision of inclusive education for deaf students.

5. Results and Discussion

This section presents the results obtained through document analysis, review of the content of the Virtual Learning Environment (VLE) and semi-structured interviews with teachers, coordinators and deaf students.

The results are organised into four sections: (1) availability, characteristics and use of inclusive materials in distance education programmes; (2) challenges faced by teachers in producing accessible materials; (3) institutional support and training; and (4) integration of LIBRAS in teaching and learning.

5.1. Availability, Characteristics, and Use of Inclusive Materials in Distance Learning Programmes

The resources identified in the university’s VLE for teaching and interaction with students and tutors were chat, forum, glossary, wikis, assessment activities, questionnaires, and tasks. A brief description of these tools is presented below.

The characterisation of these digital educational tools was based on the Teaching Guide of the CIED/UFAL, developed during the COVID-19 pandemic to support teachers in planning virtual classes for undergraduate and postgraduate programmes, whether taught remotely or in a hybrid format.

Characterisation

The chat module allows synchronous discussions in real time over the internet, while the forum facilitates asynchronous interaction between teachers, tutors and students for the discussion of specific topics. The glossary function allows for the collaborative construction and continuous updating of thematic dictionaries. Quizzes serve as assessment tools, offering various formats, such as multiple choice, true/false and matching questions. Finally, wikis allow students to collaboratively create and edit documents based on topics proposed by the teacher, fostering cooperative learning and co-construction of content.

5.2. Challenges Faced by Teachers in Producing Accessible Materials

The analysis of 657 teaching resources from 20 distance learning courses at UAB/UFAL, as shown in

Figure 1, revealed a strong predominance of written and textual materials—particularly books in PDF format, discussion forums, and quizzes (assessment activities). In the forums alone, 4145 messages were posted in 18 of the 20 subjects analysed—two subjects related to LIBRAS did not use this resource. These messages were exchanged between 2336 students, 46 tutors and 20 teachers. The forums were used to share institutional communications, clarify doubts, and assess learning. However, no course used written sign language, and only a few subjects (20%) incorporated videos with LIBRAS content.

According to the distance learning teachers surveyed, 70% stated that their materials had not been adapted to meet the needs of deaf students, while 30% responded with uncertainty or delegated responsibilities to other departments. This pattern reflects the lack of coordination and institutional guidance to produce inclusive digital content.

In contrast to distance learning programme teachers, deaf teachers in the face-to-face Libras Language programme demonstrated greater engagement with inclusive practices. Although limited by a lack of resources and institutional support, they regularly adapted teaching materials using visual strategies, simplified texts in Portuguese, and selected LIBRAS video content—mainly from open sources such as YouTube.

The responses also revealed the absence of a standardised approach or institutional guidelines for adapting materials, as illustrated by the following comments:

PS1 “I use some texts in Portuguese; I organise the content and make adaptations so that students understand Libras. I always make adaptations.”

PS2 “I take videos from YouTube and make them available for deaf students to study at home because they cannot understand the text written in Portuguese. During class, I supplement them. Each teacher makes visual adaptations to these materials, with slides, examples, or videos to present to deaf students.”

PS3 “The materials I use in my classes are general and adapted. I use both.”

These practices were informal and varied, lacking standardisation, but they reflected a deeper pedagogical commitment and cultural awareness of the specific linguistic needs of deaf students. This reinforces the importance of involving deaf educators in content development, given their first-hand understanding of what accessibility entails.

Thematic analysis of interviews with deaf and hearing teachers revealed five main challenges: lack of formal training in LIBRAS and inclusive pedagogy; time constraints and high workload; difficulty in translating complex academic texts into LIBRAS; limited access to accessible design tools; and lack of reliable reference materials adapted for LIBRAS.

PO1 “I am not fluent in Sign Language”.

PO2 “I need training in education and special education”.

PO3 “All of them, because I am not prepared to receive deaf students in the classroom”.

PO5 “Lack of prior information about students with this difficulty in the classroom and I also need guidance on how to proceed”.

PO9 “I am not prepared or trained for this”; “Lack of time, availability or resources to translate texts into Libras”.

PS1 “There are few references in this area. Depending on the profile of the students, I make adaptations. But it’s a lot of work”.

PS2 “I have many difficulties, especially with the theoretical basis, which is very heavy; you have to read a lot and make comparisons”.

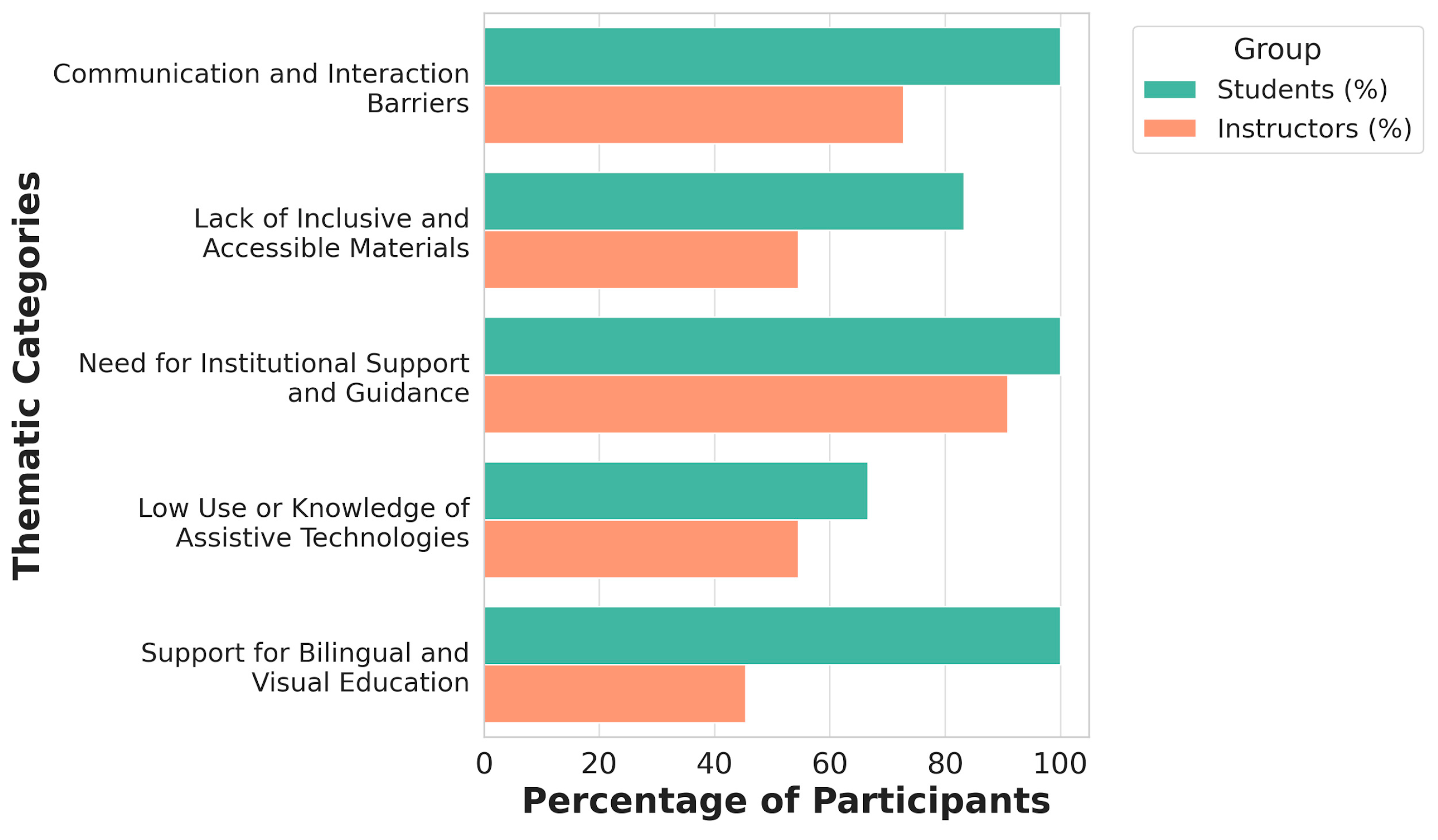

To better understand the distribution of these barriers, the responses were grouped and analysed by type of participant (students and teachers).

Figure 2 presents a comparative view of the most frequently mentioned obstacles, normalised by group size.

As shown, both groups emphasised the lack of institutional guidance and the need for bilingual and visual strategies. However, teachers more frequently reported issues related to time and tool availability, while students highlighted communicational exclusion and the ineffectiveness of machine translation tools.

5.3. Institutional Support and Training

Only one teacher among the twelve interviewed reported receiving any guidance related to the creation of accessible materials. Most were unaware of the existence of the UFAL Accessibility Centre or were unclear about its role. Several teachers pointed out the need for institutional initiatives, such as mandatory training and interdisciplinary collaboration, to support the design of inclusive teaching. Below are some testimonials from teachers about the support they received for the production of inclusive teaching materials.

PS3 “There has never been any such guidance. I organise and prepare my classes on my own”.

PO8 “I can’t see any such movements”.

PS2 “There isn’t any. I do this technical work myself…”.

The absence of a structured plan for capacity building in inclusive education, especially in distance learning programmes, was consistently cited as a barrier. In addition, when asked about the existence of multidisciplinary teams, 92% of teachers responded negatively or stated that they were unaware of such support in their courses.

When teachers were asked about the existence of a multidisciplinary team with professionals experienced in Libras and digital technologies to support the production of teaching materials and their integration into the VLE, the responses were:

PO1 “I don’t know.”

PO2 “I don’t know but based on the Accessibility Centre and the Libras course (faculty of languages), I believe there is.”

PO3 “No”

PO4 “I can’t say”

PO5 “I am not aware of it”

PO6 “I am not aware of it”

PO7 “I cannot comment on this item”

PO8 “This is one of the major problems in all public institutions, as there is a general shortage of IT professionals… I am not aware of any trained professionals assigned to these Digital Technology activities with an accessibility profile."

PO9 “I am not aware of any.’

The teachers’ responses indicate a possible failure to publicise specialised teams, such as the Accessibility Centre (NAC). This was deduced because there were inconsistencies between the information provided by the teachers and what is officially described on the UFAL website and in Normative Instruction No. 05/2018/PROEST (

Universidade Federal de Alagoas, 2018). This standard establishes that the NAC, linked to the Directorate of Student Affairs (PROEST), is an existing and functional structure, as detailed in the following articles:

Article 1: The NAC aims to ensure access, retention, and academic success for students with disabilities, autism spectrum disorder, and high abilities/giftedness at UFAL […]

Article 4: The NAC mainly serves undergraduate and graduate students from all UFAL campuses, in addition to involving the entire academic community (teachers and administrative staff).

Article 5: The NAC adopts an interdisciplinary approach and has a multidisciplinary team composed of special education teachers, social workers, psychologists, education specialists, Braille reviewers, sign language interpreters, assistive technology specialists, support staff, and scholarship recipients who support students with disabilities […]

Despite this failure in institutional communication, the study reveals advances in serving students and teachers with special needs.

5.4. Integration of LIBRAS in Teaching and Learning

Deaf students reported multiple communication difficulties with classmates, tutors, and staff, especially outside the LIBRAS Language programme. Their testimonials point to a pattern of social and academic isolation, exacerbated by the lack of interpreters, limited knowledge of LIBRAS among hearing individuals, and dependence on written Portuguese. These findings corroborate the existing literature on linguistic accessibility and the cognitive-linguistic incompatibility between spoken/written language and sign language users. Below are testimonials from deaf students about the difficulties they experience.

AS1 At UFAL, communication was very difficult because neither I nor the other people understood each other in writing. And when I didn’t have internet, I couldn’t talk to anyone by video call.

AS2 "At UFAL, the best place is Letras-Libras. Outside of here, we have no communication. I lip-read, but people speak too fast and I can’t understand them."

AS3 ‘It’s very difficult to communicate. I try to type (the alphabet in Libras) with hearing people. But they don’t even know how to do that (identify or sign the letters in Libras).’

AS6 ‘I went to the University Restaurant and, to find out the menu, the type of meat, I had to mime. They tried to talk to me orally and I said I was deaf, and it was difficult to communicate.’

The word cloud in

Figure 3, generated from transcripts of interviews with deaf students, highlights recurring concepts related to exclusion (barrier, difficulty, frustration; in red) and inclusion (support, visual, bilingual, interpreter; in green).

The predominance of terms related to exclusion reflects the students’ emotional response to their academic experience, while the presence of terms related to inclusion demonstrates their expectations for more equitable communication. These data reinforce the urgent need to structurally incorporate LIBRAS into higher education, not only as content, but as a legitimate language of instruction and interaction.

5.5. Discussion

Evidence indicates that, although regulations and institutional structures such as the NAC exist, their effective implementation and visibility still face significant barriers, reflecting a persistent gap between theory and practice. The predominance of PDF-based materials and the near absence of LIBRAS resources in the virtual environments analysed confirm the linguistic invisibility of deaf students in digital teaching contexts (

Silveira, 2022). The scarcity of bilingual materials (LIBRAS/Portuguese) and the absence of sign language writing further reinforce the monolingual and exclusionary logic of distance learning, which privileges written Portuguese as the primary vehicle of communication and learning.

Challenges reported by teachers—such as work overload, lack of specific training, and insufficient technical support—had already been highlighted by

Sassaki (

2005) and

Mantoan (

2006), who underscore the need for more robust and integrated institutional policies. The finding that only 8% of teachers had received guidance on producing accessible materials underscores a critical shortcoming in training and pedagogical support. This deficiency is exacerbated by the lack of active multidisciplinary teams, which stands in contrast to the intersectoral approach proposed in the literature on inclusion and accessibility (

Sassaki, 2005;

Pletsch, 2010).

In contrast, deaf teachers in the face-to-face Libras course demonstrated greater sensitivity and creativity in adapting materials, even in the absence of institutional support. This aligns with

Skliar’s (

1998) observation that deaf educators possess a deeper and more empathetic understanding of the linguistic and cultural needs of deaf students, making them key agents in inclusive pedagogical practices. The informal use of videos in LIBRAS, visual resources, and textual adaptations highlights a pedagogical expertise that remains underexplored by institutions.

The communication difficulties faced by deaf students, particularly outside the Libras course, corroborate previous studies on the social and academic isolation experienced by this population in higher education (

Ferreira, 2015;

R. M. d. Quadros, 2004). Dependence on written Portuguese, the scarcity of interpreters, and the limited familiarity of hearing students and staff with LIBRAS create exclusionary environments that directly affect student learning and retention.

This study contributes by exposing not only the technical and structural limitations of distance learning, but also the perceptions and strategies of deaf and hearing teachers as well as students, thereby broadening the understanding of the dynamics of inclusion and exclusion in digital contexts.

Finally, the absence of clear and standardised guidelines for the production of accessible materials and the lack of knowledge of the NAC’s activities on the part of teachers suggest a problem of institutional communication, which compromises the effectiveness of inclusive actions. These findings are in line with the concept of ‘symbolic inclusion’ discussed by

F. Rodrigues (

2011), in which policies and structures are formally established but fail in their daily implementation.