Inclusive Professional Learning Communities and Special Education Collaboration: A Qualitative Case Study in Texas

Abstract

1. Introduction

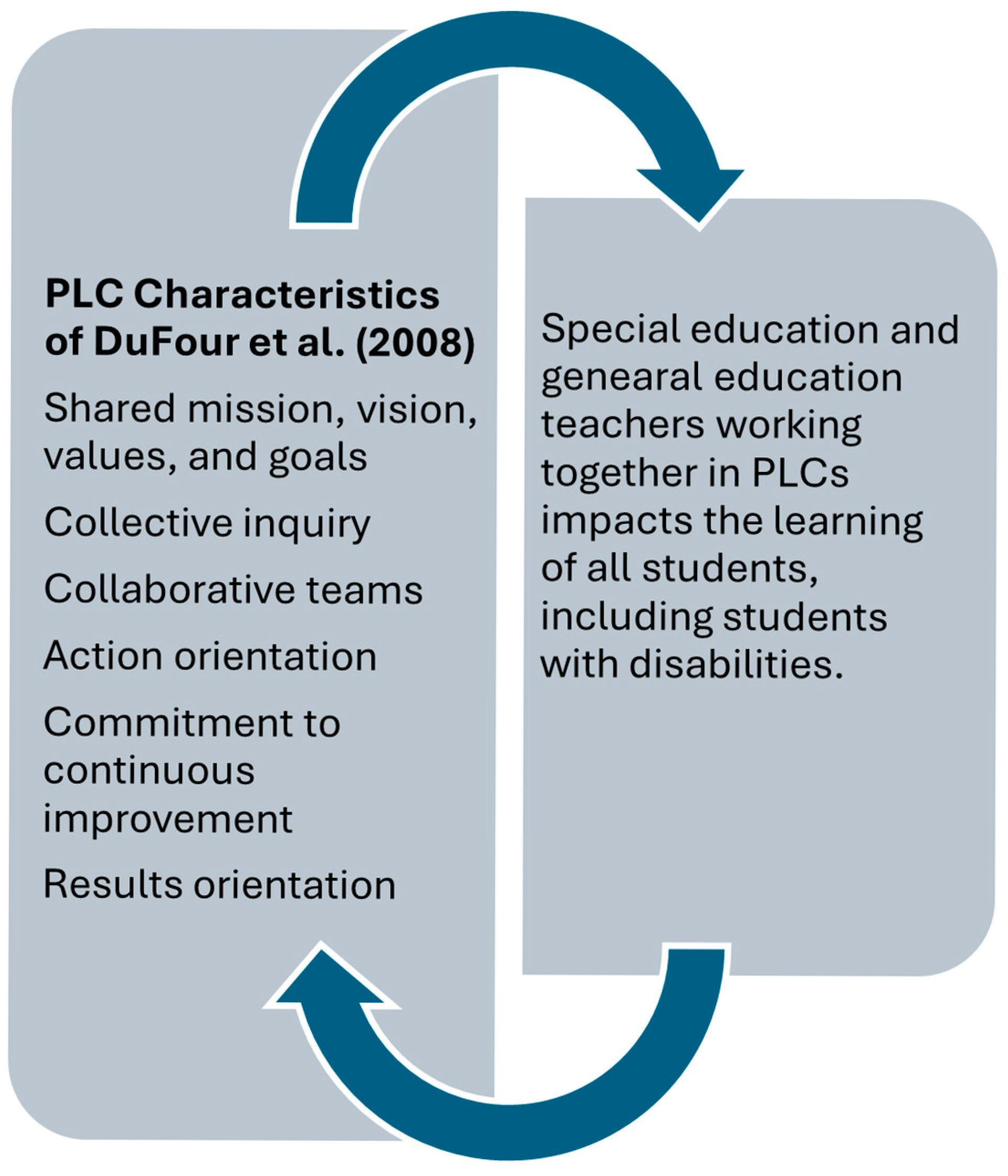

2. Professional Learning Communities

3. General Teachers and Special Education Teachers in PLCs

- When special education teachers are involved in PLCs, general education teachers will acquire more knowledge about how to work with students who are struggling in their classrooms and special education teachers will be able to make linkages between the needs of this student population and the general education curriculum.

- Special education teachers who, due to their smaller numbers and marginalization and isolation from the general education teachers, will become a more central participant within the school community through their involvement in PLCs which, in turn, will contribute to a shared culture of learning and safe environment for addressing key educational issues within the school.

4. Conceptual Framework

5. Method

5.1. Context of the Study

5.2. Participant Selection

5.3. Data Collection Tool and Procedures

5.4. Data Analysis Strategies

6. Positionality

7. Findings

7.1. Theme 1: Teacher Role and Function in the School Versus on PLC Teams

7.1.1. Role and Function in the School

That comment again shows alignment with the DuFour et al. (2008) PLC characteristic of action and results orientation, as well as the characteristic of collective inquiry.Their job is to support. Well, I mean, really, it’s a team effort, to support the students in being successful with the content that’s being taught. So, the special education teacher is there to support what’s already happening in the classroom. And then I believe the gen ed teacher and the special education teacher should work in a collaborative team to make sure that the students are being successful with that content.

After a pause, Teacher F added several non-instructional duties that general education teachers are expected to fulfill, based on “whatever the principal asks you to do or any extra thing like lunch duty, after school duty or tutoring.” Other special education teachers’ responses were shorter as they stated that it would take forever to answer the question but noted that the role of a general education teacher is to give the students everything that they need to be successful in the future. Regarding the comments about general education teachers, the special education teachers showed an understanding of the DuFour et al. (2008) characteristic of action orientation.Elementary general education teachers] are in charge of at least 20 students, their social wellbeing, their emotional wellbeing, and their academic success. She or he needs to make contact and relationships with parents and build relationships with each of the students. Otherwise, she’s not going to get any of that social and emotional success or academic success. You are responsible for them all day long, minus the 30 or 40 min you get when they go somewhere else; I mean to rotations. Then of course, understanding of all the required TEKS for whatever grade level that you teach.

7.1.2. Role and Function in the PLC

After a benchmark assessment, we will sit down, and we will talk about students. What areas were low, what areas where high, and how do we need to address those low areas together, especially with some of our special education students, and what things could be planned with those teachers, so that when she has got them and she is working with them, if she pulls them out in her classroom, she knows what their areas of weakness are and what we are targeting in class.

In our PLC, we came together, and we collaborated on different hands-on activities that our students can do. We call them arcs, like hands-on bucket activities. It’s kind of like in elementary school where the students go and get the bucket. Once they master that bucket, they can put it back and get another one. We decided to incorporate those activities on the high school level. And some of them are group activities and some are independent. But all of the teachers, and our special education teachers for the English team, we all work together on those, coming up with ideas.

Teacher K stated that the special education teachers in her PLC assist her in teaching the content to all students and finding ways to support all her students.[T]he SPED teachers, their job is to basically make sure that we’re looking at data and comparing it to what their accommodations are actually helping us achieve. If there are some that need to be taken away or some that need to be modified, things like that, that is their job to make sure, because with all the technical jargon, everything that we don’t have, they actually pull in for us and clarify questions that we may have, or they actually give us ideas as well, for ways that we can facilitate those accommodations in certain activities that we do.

7.2. Theme 2: Teacher Teamwork

7.2.1. Team Effort and Collaboration

7.2.2. Special Education Teacher’s Knowledge About How Students Learn and Their Contribution to Student Achievement

We were talking about Cleopatra and how she croaked, and a lot of students might not know who Cleopatra is. So, I had suggested to show a National Geographic five-minute YouTube video to give the kids some background knowledge. That’s one way that I try to not only strengthen those SPED students in the room but the general education students as well.

I can teach them [teachers] a way to present material. Okay, well, the students learn this way. The teacher actually comes back and says, oh, that actually works for like three of my kids. All three do really well. And the other two are not special education, they’re just general education students that have that preferred learning style.

Teacher B further stated that the special education teacher’s commitment to growth inspired her to learn new instructional strategies to share with the team.I feel like the input that our special education teachers give us in PLC, it adjusts and affects my teaching strategies every single time we talk. All the input that they give us on their students that they’re working with or the things that they’ve seen be successful with a group of students, they openly share that information with us all the time. My inclusion teacher is constantly learning and growing, and she is constantly sharing that information with me.

Other general education teachers agreed and were supportive of the learning the special education teachers provide.I’m all for whichever way the kid learns best. So, if they learn from a different method, then I’m fine with you using that. But it was a way that I was never taught. So, seeing them factor that way was pretty cool and the kids really liked it. That’s one way that I have changed my teaching due to special education teachers.

There are things that she has a little bit more knowledge on, like how to get something across to a special ed student that some of us are not getting. And so there have been times when yes, she has been able to say, “With these kinds of students, you are going to need to do this.” And so, she’s been able to explain, “Well, in my room, I take it step by step. I do this. These are the things that we’re doing with this. We are using pictures to do this.”

7.2.3. Special Education Teachers Feeling Like a Part of the PLC Team

7.2.4. PLC Team Involvement Leads to Changing One’s Instructional Practice

7.2.5. Wish Lists and Recommendations for Improvement

8. Discussion

8.1. Teacher Role and Function in the School Versus on PLC Teams

8.2. Teacher Teamwork

8.3. Implications for Practice and Recommendations for Research

8.4. Limitations

9. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. One-On-One Interview Questions

- Talk to me about how the special education/general education teacher functions on your campus.

- How do they function as a member of your PLC?

- What kind of contributions or insights do they bring to the overall functioning of your PLC team?

- Please discuss your participation in PLC team meetings.

- What role do you play in the growth of students?

- What role do general education/special education teachers play in supporting each other in the PLC team and student learning?

- Describe examples of your contributions in PLC meetings that have led to increased student achievement.

- Share a time when the participation of general education/special education teachers in a PLC team meeting worked well together to improve students’ academic performance.

- Share a time during your PLC team meetings when the input of a special education/general education teacher changed the general education teacher’s instructional practice.

- Can you think of any additional examples?

- Describe a time during a PLC meeting when a special education teacher/general education teacher filled the knowledge gap of the other?

- Describe a time during your PLC team meetings when a special education/general education teacher supported and changed the growth of general education/special education teachers in how students learn.

- If you had three wishes for making your PLCs team more effective, what would they be?

- Do you have any final comments or anything else you want to add?

References

- Ahn, J., Flores, O. J., Welton, A. D., & Hackmann, D. G. (2024). Challenges in sustaining professional learning communities focused on equity. Journal of Educational Change, 26(1), 57–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bemiller, M. (2019). Inclusion for all? An exploration of teacher’s reflections on inclusion in two elementary schools. Journal of Applied Social Science, 13(1), 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanton, L. P., & Perez, Y. (2011). Exploring the relationship between special education teachers and professional learning communities: Implications of research for administrators. Journal of Special Education Leadership, 24(1), 6–16. [Google Scholar]

- Boom-Muilenburg, S. N., Vries, S., Veen, K., Poortman, C. L., & Schildkamp, K. (2021). Understanding sustainable professional learning communities by considering school leaders’ interpretations and educational beliefs. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 27(4), 934–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brantlinger, E., Jimenez, R., Klingner, J., Pugach, M., & Richardson, V. (2005). Qualitative studies in special education. Exceptional Children, 71(2), 195–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clausen, A. M., Anderson, A., Spooner, F., Walker, V. L., & Hujar, J. (2023). Preparing general education teachers to include students with extensive support needs: An analysis of “SPED 101” courses. Teacher Education and Special Education, 46(2), 146–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornelius, K. E., & Gustafson, J. A. (2021). Relationships with school administrators: Leveraging knowledge and data to self-advocate. Teaching Exceptional Children, 53(3), 206–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2022). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (6th ed.). Sage. [Google Scholar]

- De Neve, D., Devos, G., & Tuytens, M. (2015). The importance of job resources and self-efficacy for beginning teachers’ professional learning in differentiated instruction. Teaching and Teacher Education, 47, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dooley, K. (2021). Legislative update: Training and staff development. Texas Association of School Boards. Available online: https://www.tasb.org/services/hr-services/hrx/hr-laws/legislative-update-raining-and-staff-development.aspx (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- DuFour, R., DuFour, R., & Eaker, R. (2008). Revisiting professional learning communities at work: New insights for improving schools. Solution Tree. [Google Scholar]

- DuFour, R., DuFour, R., Eaker, R., Many, T. W., & Mattos, M. (2016). Learning by doing (3rd ed.). Solution Tree Press. [Google Scholar]

- Endrew F. v. Douglas County School District. (2017). 137 S. Ct. 988. Available online: https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/580/15-827/ (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- Goddard, A. K. (2023). Transforming Arkansas schools: Leadership practices to promote the inclusion of students with disabilities [Ph.D. dissertation, Arkansas State University]. ProQuest database (Order No. 30690673). [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, J. L. (2013). Professional learning communities’ impact on student achievement [Ph.D. dissertation, Saint Mary’s College of California]. ProQuest database (Order No. 3568312). [Google Scholar]

- Hesse-Biber, S. N. (2017). The practice of qualitative research (3rd ed.). Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Hord, S. M. (2009). Professional learning communities: Educators work together toward a shared purpose—Improve student learning. Journal of Staff Development, 30(1), 40–43, 78. [Google Scholar]

- Jarvie, L., & Waldow, J. (2021). Professional learning communities: An inclusive solution for engagement and collaboration. In D. Aucoin (Ed.), Building integrated collaborative relationships for inclusive learning settings (pp. 216–239). IGI Global. [Google Scholar]

- King-Sears, M. E., Stefanidis, A., Berkeley, S., & Strogilos, V. (2021). Does co-teaching improve academic achievement for students with disabilities? A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 34(1), 100405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovett, B. J. (2021). Educational accommodations for students with disabilities: Two equity-related concerns. Frontiers in Education, 6, 795266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McConnell, T. J., Parker, J. M., Eberhardt, J., Koehler, M. J., & Lundeberg, M. A. (2012). Virtual professional learning communities: Teachers’ perceptions of virtual versus face-to-face professional development. Journal of Science Educational Technology, 22, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeskey, J., Maheady, L., Billingsley, B., Brownell, M. T., & Lewis, T. J. (Eds.). (2019). High leverage practices for inclusive classrooms. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Merriam, S. B. (1998). Qualitative research and case study applications in education (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Middlestead, A. (2020). Do local educators need to care about independent alignment studies of summative assessments? Educational Measurement: Issues & Practice, 39(2), 35. Available online: https://doi-org.libproxy.library.unt.edu/10.1111/emip.12335 (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- No Child Left Behind Act of 2001. (2002). Pub. L. No. 107–110, 115 Stat. 1425. Available online: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/PLAW-107publ110/pdf/PLAW-107publ110.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- Overall, C. P. (2021). Exploring the impact of special education professional learning communities on students with disabilities [Ph.D. dissertation, Middle Tennessee State University]. ProQuest database (Order No. 28412121). [Google Scholar]

- Paulsrud, D., & Nilholm, C. (2023). Teaching for inclusion: A review of research on the cooperation between regular teachers and special educators in the work with students in need of special support. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 27(4), 541–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prince, A. M. T., Yell, M. L., & Katsiyannis, A. (2017). Endrew F. v. Douglas County School District (2017): The U.S. Supreme Court and special education. Intervention in School and Clinic, 53(5), 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasberry, M. A., & Mahajan, G. (2008, September). From isolation to collaboration: Promoting teacher leadership through PLCs (pp. 1–24). Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED503637 (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- Robbins, S. C. (2013). A study of teachers’ perceptions of participating in professional learning communities and the relationships between general and special education [Ph.D. dissertation, The University of North Carolina at Greensboro]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global; Social Science Premium Collection (Order No. 3592831). [Google Scholar]

- Schechter, C., & Feldman, N. (2019). The principal’s role in professional learning community in a special education school serving pupils with autism. Journal of Special Education Leadership, 32(1), 17–28. [Google Scholar]

- Senge, P. M. (1990). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. Doubleday/Currency. [Google Scholar]

- Senge, P. M. (2000). A fifth discipline resource: Schools that learn. Doubleday. [Google Scholar]

- TEA. (2019). Texas Education Agency 2019 STAAR performance. Available online: https://bit.ly/2TCJZWd (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- Thacker, T. D. (2013). Professional learning communities: An analysis of fifth grade special education student achievement and teacher longevity in two Texas school districts [Ph.D. dissertation, Texas A&M University—Commerce]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global; Social Science Premium Collection (Order No. 3595359). [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull, H. R., Turnbull, A. P., & Cooper, D. H. (2018). The Supreme Court, Endrew, and the appropriate education of students with disabilities. Exceptional Children, 84(2), 124–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Education. (2015). Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). Available online: https://www.ed.gov/laws-and-policy/laws-preschool-grade-12-education/every-student-succeeds-act-essa (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- U.S. Department of Education. (2017, March). Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA). 20 U.S.C. § 1232g; 34 CFR Part 99. Available online: https://studentprivacy.ed.gov/resources/family-educational-rights-and-privacy-act-regulations-ferpa (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- U.S. Department of Education. (2024, March). 45th annual report to Congress on the implementation of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, 2023. Available online: https://sites.ed.gov/idea/files/45th-arc-for-idea.pdf (accessed on 3 June 2025).

- Voelkel, R. H., & Chrispeels, J. H. (2017). Within school differences in professional learning community effectiveness: Implications for leadership. Journal of School Leadership, 27(3), 421–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voelkel, R. H., Fiori, C., & van Tassell, F. (2021). District leadership in redefining roles of instructional coaches to guide professional learning communities through systemic change. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 22(1), 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wexler, J., Shelton, A., Stark, K., Hogan, E., Chow, J., & Fisk, R. (2024). Professional development as a pathway for sustaining teachers. In E. D. McCray, E. Bettini, M. T. Brownell, J. McLeskey, & P. T. Sindelar (Eds.), Handbook of research on special education teacher preparation (pp. 319–340). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Woulfin, S. L., & Jones, B. (2021). Special development: The nature, content, and structure of special education teachers’ professional learning opportunities. Teaching and Teacher Education, 100, 103277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pseudonym | Grade Level Group | Teaching Assignment | Content Area |

|---|---|---|---|

| Teacher A | Elementary | General Education | Reading |

| Teacher B | High School | General Education | Reading |

| Teacher C | Elementary | Special Education | Reading |

| Teacher D | High School | Special Education | Reading |

| Teacher E | High School | General Education | Mathematics |

| Teacher F | Elementary | Special Education | Mathematics |

| Teacher G | Middle School | General Education | Reading |

| Teacher H | Middle School | Special Education | Mathematics |

| Teacher I | High School | Special Education | Mathematics |

| Teacher J | Middle School | Special Education | Reading |

| Teacher K | Middle School | General Education | Mathematics |

| Teacher L | Elementary | General Education | Mathematics |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wilshire, J.M., II; Voelkel, R.H., Jr.; Pazey, B.; Van Tassell, F. Inclusive Professional Learning Communities and Special Education Collaboration: A Qualitative Case Study in Texas. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1279. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101279

Wilshire JM II, Voelkel RH Jr., Pazey B, Van Tassell F. Inclusive Professional Learning Communities and Special Education Collaboration: A Qualitative Case Study in Texas. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1279. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101279

Chicago/Turabian StyleWilshire, John Mark, II, Robert H. Voelkel, Jr., Barbara Pazey, and Frances Van Tassell. 2025. "Inclusive Professional Learning Communities and Special Education Collaboration: A Qualitative Case Study in Texas" Education Sciences 15, no. 10: 1279. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101279

APA StyleWilshire, J. M., II, Voelkel, R. H., Jr., Pazey, B., & Van Tassell, F. (2025). Inclusive Professional Learning Communities and Special Education Collaboration: A Qualitative Case Study in Texas. Education Sciences, 15(10), 1279. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101279