What Role Does Occupational Well-Being During Practical Field Experiences Play in Pre-Service Teachers’ Career-Oriented Reflections?

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Career-Oriented Reflection in Teacher Education

1.2. Occupational Well-Being in Teacher Education

1.3. Connections Between Occupational Well-Being and Reflection in Teacher Education

1.4. Present Study

- How does the field experience change job satisfaction as well as positive and negative emotions of pre-service teachers?

- 2.

- Which career-oriented reflection processes do pre-service teachers report after the field experience?

- 3.

- Can pre-service teachers’ occupational well-being predict their career-oriented reflections?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design and Sample

2.2. Instruments

2.2.1. Career-Oriented Reflection

2.2.2. Occupational Well-Being

2.3. Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Changes in Occupational Well–Being

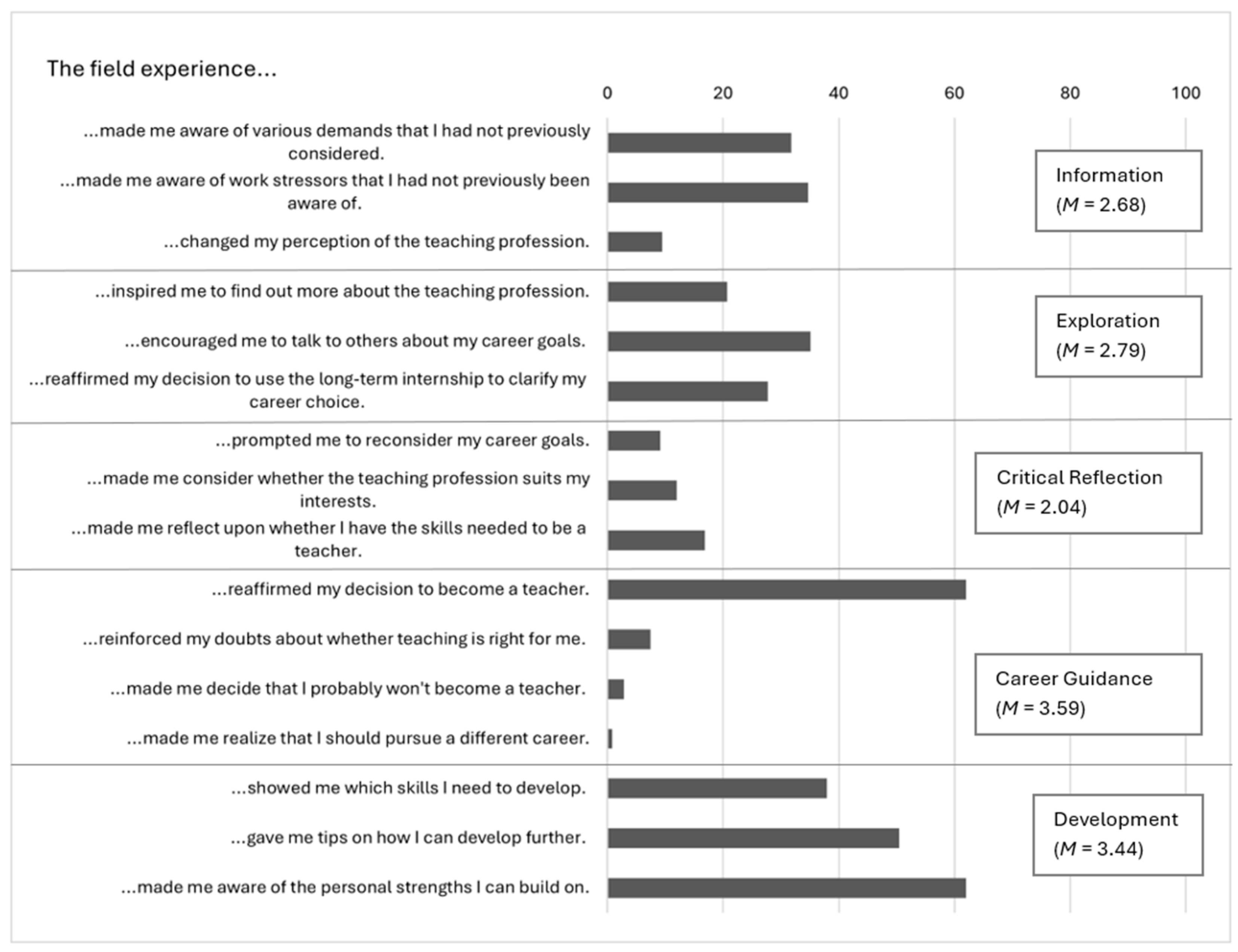

3.3. Career-Oriented Reflection Processes

3.4. Influence of Occupational Well-Being on Career-Oriented Reflection

4. Discussion

4.1. Practical Implications

4.2. Limitations and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviation

| PFE | Practical field experience |

References

- Aliakbari, M., Khany, R., & Adibpour, M. (2019). EFL teachers’ reflective practice, job satisfaction, and school context variables: Exploring possible relationships. TESOL Journal, 11, e00461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arendt, K., Stark, L., Friedrich, A., Brünken, R., & Stark, R. (2025). Reflexion von unterricht in der lehrkräftebildung—Ein scoping-review. Unterrichtswissenschaft, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arens, A. K., & Morin, A. J. S. (2016). Relations between teachers’ emotional exhaustion and students’ educational outcomes. Journal of Educational Psychology, 108(6), 800–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, K. H., Gröschner, A., & Hascher, T. (2014). Pedagogical field experiences in teacher education: Introduction to the research area. In K. H. Arnold, A. Gröschner, & T. Hascher (Eds.), Schulpraktika in der Lehrerbildung/Pedagogical field experiences in teacher education. Theoretische Grundlagen, Konzeptionen, Prozesse und Effekte/Theoretical foundations, programmes, processes, and effects (pp. 11–28). Waxmann. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumert, J., Blum, W., Brunner, M., Dubberke, T., Jordan, A., Klusmann, U., Krauss, S., Kunter, M., Löwen, K., Neubrand, M., & Tsai, Y.-M. (2009). Professionswissen von Lehrkräften, kognitiv aktivierender Mathematikunterricht und die Entwicklung von mathematischer Kompetenz (COACTIV): Dokumentation der Erhebungsinstrumente. Max-Planck-Institut für Bildungsforschung. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, K., Opara-Nadi, L. K., & Catchings-Shelby, K. (2024). Supporting the well-being of pre-service teachers during field practice. Journal of Education and Human Development, 13(2), 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caires, S., Almeida, L., & Vieira, D. (2012). Becoming a teacher: Student teachers’ experiences and perceptions about teaching practice. European Journal of Teacher Education, 35(2), 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choy, D., Wong, A. F. L., Chuan Goh, K., & Ling Low, E. (2013). Practicum experience: Pre-service teachers’ self-perception of their professional growth. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 51(5), 472–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarà, M. (2015). What is reflection? Looking for clarity in an ambiguous notion. Journal of Teacher Education, 66(3), 261–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, E., Hoz, R., & Kaplan, H. (2013). The practicum in preservice teacher education: A review of empirical studies. Teaching Education, 24(4), 345–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, L. M., Clifton, R. A., Perry, R. P., Mandzuk, D., & Hall, N. C. (2006). Student teachers’ competence and career certainty: The effects of career anxiety and perceived control. Social Psychology of Education, 9, 405–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darge, K., Valtin, R., Kramer, C., Ligtvoet, R., & König, J. (2018). Die Freude an der Schulpraxis: Zur differenziellen Veränderung eines emotionalen Merkmals von Lehramtsstudierenden während des Praxissemesters. In J. König, M. Rothland, & N. Schaper (Eds.), Learning to practice, learning to reflect? Ergebnisse aus der Längsschnittstudie LtP zur Nutzung und Wirkung des Praxissemesters in der Lehrerbildung (pp. 241–264). Springer VS. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands–resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewey, J. (1933). How we think: A restatement of the relation of reflective thinking to the educative process. D.C. Heath. [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125(2), 276–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreer, B. (2023). Witnessing well-being in action: Observing teacher well-being during field experiences predicts student teacher well-being. Frontiers in Education, 8, 967905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eğinli, İ., & Solhi, M. (2021). The impact of practicum on pre-service EFL teachers’ self-efficacy beliefs: First step into professionalism. Shanlax International Journal of Education, 9(4), 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eren, A. (2017). Professional aspirations among pre-service teachers: Personal responsibility, time perspectives, and career choice satisfaction. The Australian Educational Researcher, 44, 275–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Festinger, L. (1957). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56, 218–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenzel, A. C., Goetz, T., Lüdtke, O., Pekrun, R., & Sutton, R. E. (2009). Emotional transmission in the classroom: Exploring the relationship between teacher and student enjoyment. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101, 705–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, P. S., & Matthews, B. (2011). Listening to the concerns of student teachers in Malaysia during teaching practice. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 36(3), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isen, A. M. (1984). Toward understanding the role of affect in cognition. In R. S. Wyer, & T. K. Srull (Eds.), Handbook of social cognition (Vol. 3, pp. 179–236). Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Y., Oubibi, M., Chen, S., Yin, Y., & Zhou, Y. (2022). Pre-service teachers’ emotional experience: Characteristics, dynamics and sources amid the teaching practicum. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 968513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, R. M., & Chiu, M. M. (2011). The occupational commitment and intention to quit of practicing and pre-service teachers: Influence of self-efficacy, job stress, and teaching context. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 36(2), 114–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleinknecht, M., & Schneider, J. (2013). What do teachers think and feel when analyzing videos of themselves and other teachers teaching? Teaching and Teacher Education, 33, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klusmann, U., Kunter, M., Trautwein, U., Lüdtke, O., & Baumert, J. (2008). Teachers’ occupational well-being and quality of instruction: The important role of selfregulatory patterns. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100(3), 702–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KMK. (2013). Empfehlungen zur Eignungsabklärung in der ersten Phase der Lehrerausbildung. Available online: https://www.kmk.org/fileadmin/veroeffentlichungen_beschluesse/2013/2013-03-07-Empfehlung-Eignungsabklaerung.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Korthagen, F. A. J., & Wubbels, T. (1995). Characteristics of reflective practitioners: Towards an operationalization of the concept of reflection. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice, 1(1), 51–72. [Google Scholar]

- König, J., Darge, K., & Kramer, C. (2020). Kompetenzentwicklung im Praxissemester: Zur Bedeutung schulpraktischer Lerngelegenheiten auf den Erwerb von pädagogischem Wissen bei Lehramtsstudierenden. In I. Ulrich, & A. Gröschner (Eds.), Praxissemester im Lehramtsstudium in Deutschland: Wirkungen auf studierende (Edition ZfE 9) (pp. 67–96). Springer VS. [Google Scholar]

- Krohne, H. W., Egloff, B., Kohlmann, C.-W., & Tausch, A. (1996). Untersuchungen mit einer deutschen Version der “Positive and Negative Affect Schedule” (PANAS). Diagnostica, 42, 139–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhbandner, C., & Frenzel, A. C. (2019). Emotionen. In D. Urhahne, M. Dresel, & F. Fischer (Eds.), Psychologie für den Lehrberuf (pp. 185–206). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Kumschick, I. R., Thiel, F., Goschin, C., & Froehlich, E. (2020). Decision-making in teaching processes and the role of mood: A study with preservice teachers in Germany. International Journal of Emotional Education, 12(2), 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, T., Cakmak, M., Gündüz, M., & Busher, H. (2015). Research on teaching practicum—A systematic review. European Journal of Teacher Education, 38(3), 392–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenske, G., & Lohse-Bossenz, H. (2023). Stichwort: Reflexion im pädagogischen Kontext. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 26, 1133–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lermer, S., Mayr, J., & Nieskens, B. (2017). Reflektieren vor dem Studieren. Online-Beratung und Praktikum als Einstieg in die Lehrerlaufbahn. In C. Berndt, T. Häcker, & T. Leonhard (Eds.), Reflexive Lehrerbildung revised. Traditionen—Zugänge—Perspektiven (pp. 105–115). Julius Klinkhardt. [Google Scholar]

- Lohse-Bossenz, H., Lenske, G., & Westphal, A. (2025). Let me think about it—Establishing. “Need to reflect” as a motivational variable in reflection processes. Education Sciences, 15(6), 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohse-Bossenz, H., Schmitt, M., & Lenske, G. (2023). „The same or different?”—Effekte von Unterrichtsanalyse und Unterrichtsreflexion auf die Veränderung kognitiver und motivationaler Merkmale professioneller Lehrkompetenz. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 26, 1281–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K., & Cavanagh, M. S. (2018). Classroom ready? Pre-service teachers’ self-efficacy for their first professional experience placement. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 43(7), 134–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R. L. C., & Phillips, L. H. (2007). The psychological, neurochemical and functional neuroanatomical mediators of the effects of positive and negative mood on executive functions. Neuropsychologia, 45(4), 617–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moors, A., Ellsworth, P. C., Scherer, K. R., & Frijda, N. H. (2013). Appraisal theories of emotion: State of the art and future development. Emotion Review, 5(2), 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, P. T., Lim, K. M., Low, E. L., & Hui, C. (2018). Provision of early field experiences for teacher candidates in Singapore and how it can contribute to teacher resilience and retention. Teacher Development, 22(5), 632–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekrun, R. (2006). The control-value theory of achievement emotions: Assumptions, corollaries, and implications for educational research and practice. Educational Psychology Review, 18(4), 315–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porsch, R., & Gollub, P. (2018). Angst zu unterrichten bei Lehramtsstudierenden vor und nach dem Praxissemester. In L. Pilypaitytė, & H. S. Siller (Eds.), Schulpraktische Lehrerprofessionalisierung als Ort der Zusammenarbeit (pp. 237–245). Springer VS. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, C. (2002). Defining reflection: Another look at John Dewey and reflective thinking. Teachers College Record, 104(4), 842–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvagioni, D. A. J., Melanda, F. N., Mesas, A. E., Gonz’alez, A. D., Gabani, F. L., & de Andrade, S. M. (2017). Physical, psychological and occupational consequences of job burnout: A systematic review of prospective studies. PLoS ONE, 12(10), e0185781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scherer, K. R. (2000). Psychological models of emotion. In J. C. Borod (Ed.), The neuropsychology of emotion (pp. 137–162). Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schulze-Hagenest, T., Carstensen, B., Weber, K. E., Jansen, T., Meyer, J., Köller, O., & Klusmann, U. (2023). Teachers’ emotional exhaustion and job satisfaction: How much does the school context matter? Teaching and Teacher Education, 136, 104360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, A., & Schaper, N. (2018). Die Veränderung von Selbstwirksamkeitserwartungen und der Berufswahlsicherheit im Praxissemester. Empirische Befunde zur Bedeutung von Lerngelegenheiten und berufsspezifischer Motivation der Lehramtsstudierenden. In J. König, M. Rothland, & N. Schaper (Eds.), Learning to practice, learning to reflect? Ergebnisse aus der Längsschnittstudie LtP zur Nutzung und Wirkung des Praxissemesters in der Lehrerbildung (pp. 195–222). Springer VS. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2011). Teacher job satisfaction and motivation to leave the teaching profession: Relations with school context, feeling of belonging, and emotional exhaustion. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27, 1029–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svojanovsky, P. (2017). Supporting student teachers’ reflection as a paradigm shift process. Teaching and Teacher Education, 66, 338–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, T., Wagner, W., Klusmann, U., Trautwein, U., & Kunter, M. (2017). Changes in beginning teachers’ classroom management knowledge and emotional exhaustion during the induction phase. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 51, 170–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warr, P. (1999). Well-being and the workplace. In D. Kahneman, E. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology (pp. 392–412). Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Wartenberg, G., Aldrup, K., Grund, S., & Klusmann, U. (2023). Satisfied and high performing? A meta-analysis and systematic review of the correlates of teachers’ job satisfaction. Educational Psychology Review, 35, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, K. E., Prilop, C. N., & Kleinknecht, M. (2023). Effects of different video-or text-based reflection stimuli on pre-service teachers’ emotions, immersion, cognitive load and knowledge-based reasoning. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 77, 101256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalcin Arslan, F., & Ilin, G. (2018). The effects of teaching practicum on EFL pre-service teachers’ concerns. Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies, 14(2), 265–282. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H., & Zhang, X. (2017). The influence of field teaching practice on pre-service teachers’ professional identity: A mixed methods study. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| N | M | SD | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Affect (1) | 238 | 3.56 | 0.72 | |||||||

| Negative Affect (2) | 238 | 1.70 | 0.50 | −0.186 ** | ||||||

| Job Satisfaction (3) | 236 | 3.22 | 0.57 | 0.470 *** | −0.369 *** | |||||

| Information (4) | 240 | 2.68 | 0.75 | −0.010 | 0.209 ** | −0.212 ** | ||||

| Exploration (5) | 240 | 2.79 | 0.82 | 0.091 | 0.166 ** | −0.075 | 0.331 ** | |||

| Critical reflection (6) | 240 | 2.04 | 0.90 | −0.236 *** | 0.218 *** | −0.461 *** | 0.468 ** | 0.292 ** | ||

| Career guidance (7) | 239 | 3.59 | 0.63 | 0.314 *** | −0.153 * | 0.469 *** | −0.361 ** | −0.136 * | −0.632 ** | |

| Development (8) | 241 | 3.44 | 0.49 | 0.162 ** | 0.012 | 0.118 * | 0.141 * | 0.230 ** | −0.029 | 0.216 ** |

| Mt1 (SD) | Mt2 (SD) | ∆t2−t1 | Test Statistics | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive Affect | 3.56 (0.72) | 4.02 (0.60) | 0.46 | t(237) = −11.577, p < 0.001 |

| Negative Affect | 1.70 (0.50) | 1.63 (0.46) | −0.07 | t(237) = 2.236, p = 0.026 |

| Job Satisfaction | 3.22 (0.57) | 3.27 (0.60) | 0.05 | t(235) = −1.803, p = 0.073 |

| Information | Exploration | Critical Reflection | Career Guidance | Development | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | |||||

| positive affect | 0.117 | 0.164 * | −0.024 | 0.121 | 0.138 |

| negative affect | 0.154 * | 0.161 * | 0.056 | 0.025 | 0.066 |

| job satisfaction | −0.210 ** | −0.093 | −0.429 *** | 0.421 *** | 0.077 |

| Model 2 | |||||

| positive affect | 0.163 | 0.279 ** | −0.078 | 0.308 *** | 0.334 *** |

| negative affect | 0.253 ** | 0.213 * | 0.206 ** | −0.140 * | 0.175 * |

| job satisfaction | −0.281 *** | −0.131 | −0.469 *** | 0.457 *** | 0.119 |

| change in positive affect | 0.044 | 0.168 | −0.098 | 0.308 *** | 0.337 *** |

| change in negative affect | 0.147 | 0.097 | 0.214 ** | −0.208 *** | 0.230 ** |

| change in job satisfaction | −0.309 *** | −0.112 | −0.315 *** | 0.395 *** | 0.151 * |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.167 | 0.046 | 0.381 | 0.578 | 0.115 |

| Difference in F | 10.474 *** | 1.824 | 22.677 *** | 65.361 *** | 9.186 *** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Neuber, K.; Jacobsen, L.; Lohse-Bossenz, H.; Weber, K.E. What Role Does Occupational Well-Being During Practical Field Experiences Play in Pre-Service Teachers’ Career-Oriented Reflections? Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 1269. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101269

Neuber K, Jacobsen L, Lohse-Bossenz H, Weber KE. What Role Does Occupational Well-Being During Practical Field Experiences Play in Pre-Service Teachers’ Career-Oriented Reflections? Education Sciences. 2025; 15(10):1269. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101269

Chicago/Turabian StyleNeuber, Katharina, Lucas Jacobsen, Hendrik Lohse-Bossenz, and Kira Elena Weber. 2025. "What Role Does Occupational Well-Being During Practical Field Experiences Play in Pre-Service Teachers’ Career-Oriented Reflections?" Education Sciences 15, no. 10: 1269. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101269

APA StyleNeuber, K., Jacobsen, L., Lohse-Bossenz, H., & Weber, K. E. (2025). What Role Does Occupational Well-Being During Practical Field Experiences Play in Pre-Service Teachers’ Career-Oriented Reflections? Education Sciences, 15(10), 1269. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15101269