Characteristics of Effective Elementary Mathematics Instruction: A Scoping Review of Experimental Studies

Abstract

1. Introduction

Aim and Research Questions

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

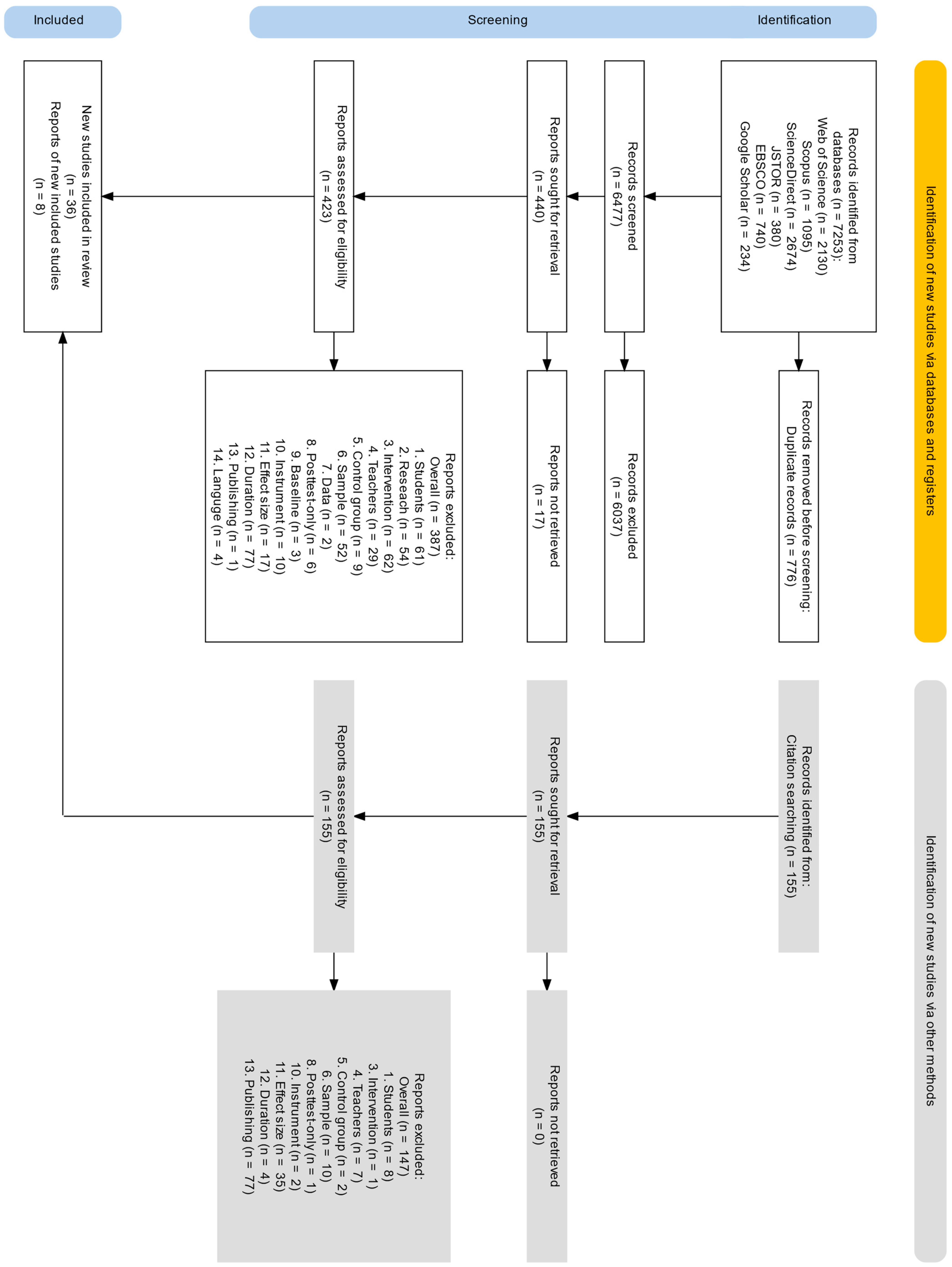

2.2. Search Strategy and Selection Studies

2.3. Extracting and Analyzing Data

3. Results and Discussion

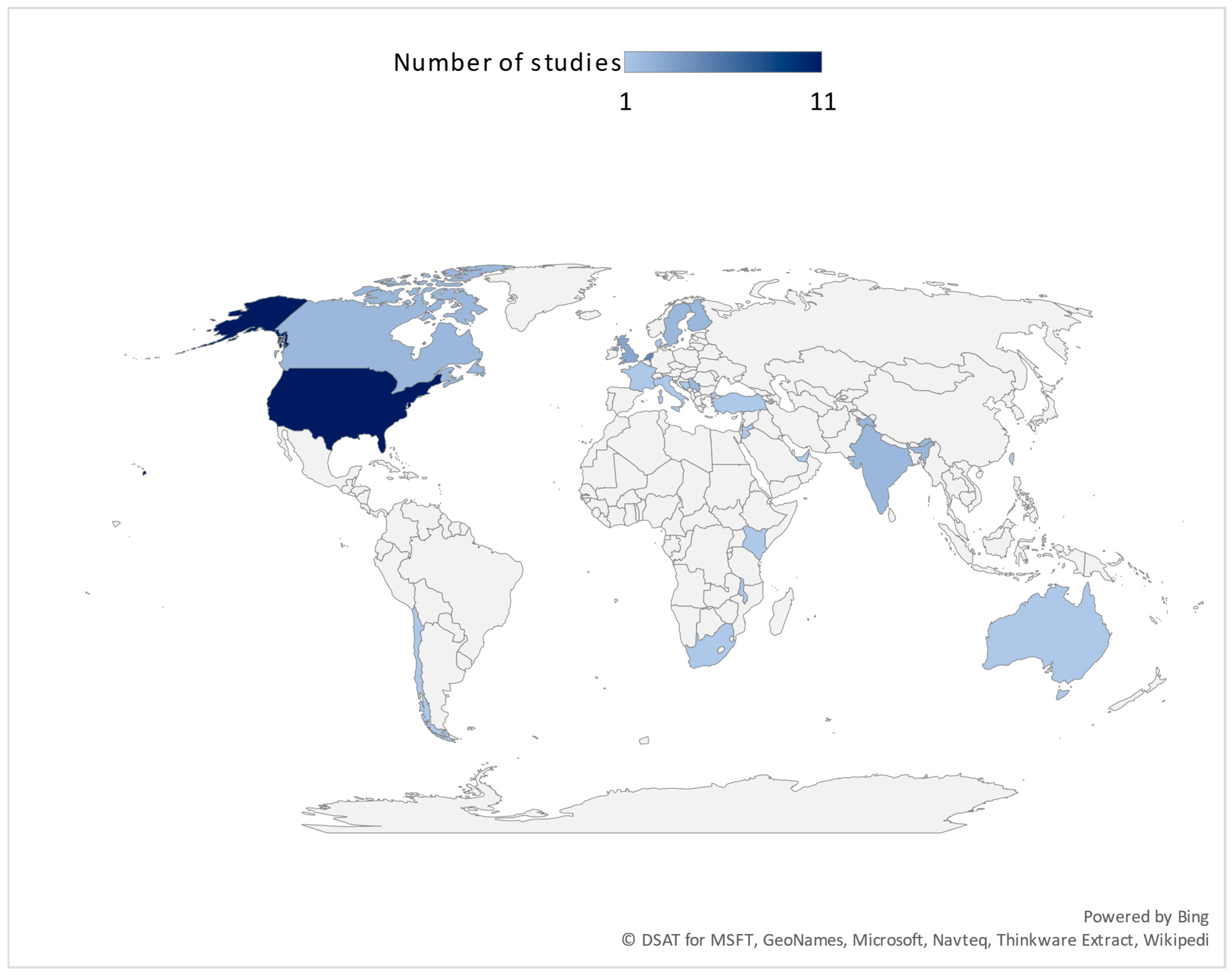

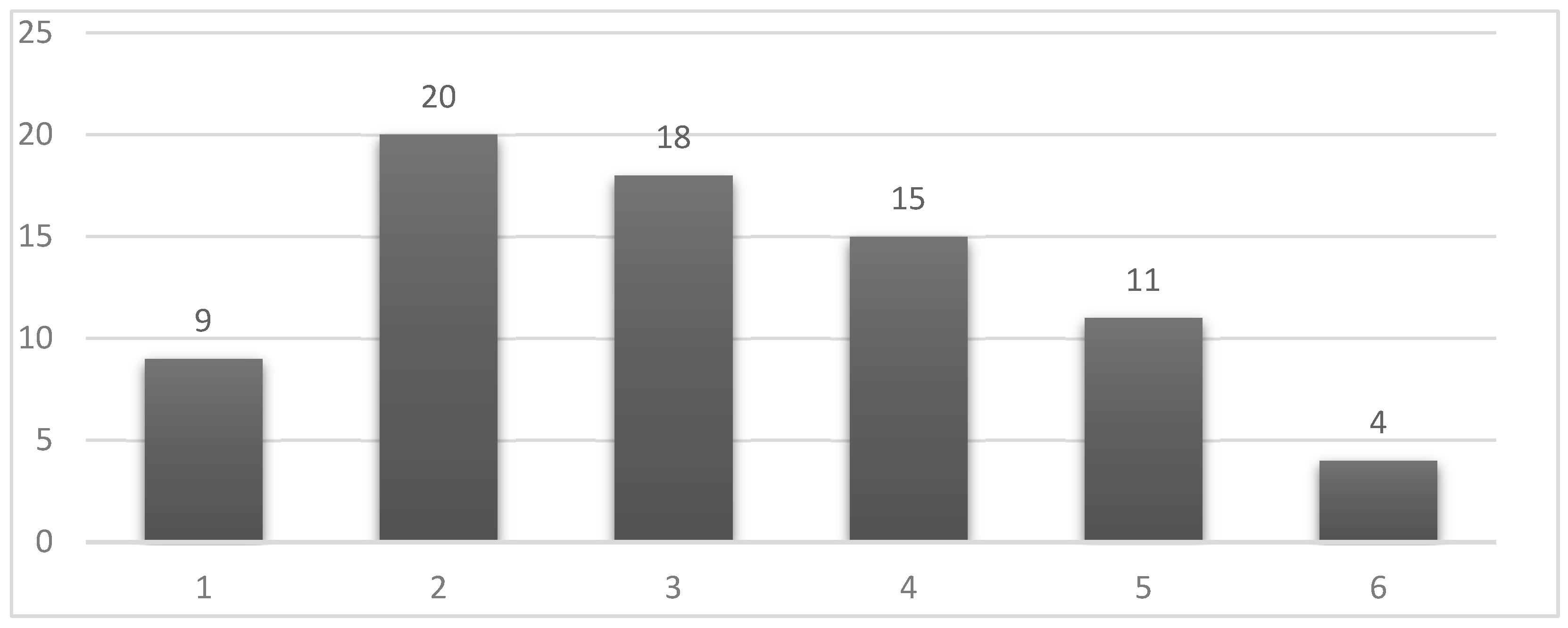

3.1. What Are the Main Characteristics of Studies That Address Effective Mathematics Interventions in Elementary School?

3.2. What Characteristics of Mathematics Instruction Are Found in the Selected Studies?

| Theme | Characteristic | Characteristic Count | Theme Count |

|---|---|---|---|

| Use of digital technology and non-digital teaching materials | Using digital technology in mathematics learning | 21 | 30 |

| Teaching materials | 12 | ||

| Cognitive engagement, conceptual understanding, and procedural fluency | Reasoning and problem-solving | 26 | 29 |

| Procedural and conceptual knowledge | 15 | ||

| Realistic mathematics education | 9 | ||

| Monitoring students’ progress and adaptivity | Feedback and formative assessment | 23 | 29 |

| Differentiation and individualization | 19 | ||

| Incremental progression | 10 | ||

| Using students’ prior knowledge | 9 | ||

| Scaffolding | 7 | ||

| Active learning and educational games | Active learning | 17 | 26 |

| Educational games | 17 | ||

| Social forms of learning | Cooperative learning | 17 | 19 |

| Frontal instruction | 11 | ||

| Individual practice | 7 | ||

| Connecting mathematical representations to enable abstract thinking | Manipulatives and visualizations | 18 | 19 |

| Multiple representations | 7 | ||

| From concrete to abstract | 6 | ||

| Mathematical communication | Mathematical discussions | 11 | 13 |

| Questioning | 6 | ||

| Metacognition | Metacognitive strategies | 12 | 13 |

| Goal setting | 6 | ||

| Analyzing students’ errors | 2 | ||

| Critical thinking | 2 | ||

| Curriculum | Integrated curriculum | 7 | 10 |

| New curriculum | 4 | ||

| Big ideas | 4 |

3.3. How Are the Identified Characteristics Applied in Elementary School Mathematics Teaching?

3.3.1. Use of Digital Technology and Non-Digital Teaching Materials

3.3.2. Cognitive Engagement and Conceptual Understanding

3.3.3. Assess Learning Progress and Adapt Teaching to the Students’ Mathematical Results

3.3.4. Active Learning and Educational Games

3.3.5. Social Forms of Learning

3.3.6. Connecting Mathematical Representations to Enable Abstract Thinking

3.3.7. Mathematical Discussions and Questioning

3.3.8. Metacognition

3.3.9. (Integrated) Curriculum

4. Conclusions

5. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix B

| (References) Intervention Title (Duration), Country (TIMSS or PISA Results 1) | Research Aim | Sample Type of Study, Type of Measurement Instrument Comparison of Hedges’ g and MDES 2 (Significance) |

|---|---|---|

| (Al-Mashaqbeh, 2016) IPad in Elementary School Math (3 months), Jordan (420) | The aim of this study was to investigate the impact of traditional teaching methods compared to the use of iPads for teaching mathematics in first grade. | 1st grade (42E, 42C) quasi-experiment, researcher-made 0.56 * > 0.55 (p = 0.01) |

| (Araya & Diaz, 2020) Government Elementary Math Exercises Online (12 weeks), Chile (441) | The aim of the study was to evaluate the effectiveness of an online math platform for primary school pupils developed by the Chilean Ministry of Education. | 4th grade (659E, 538C) RCT, standardized 0.13 < 0.14 (p < 0.04) |

| (Bakker et al., 2015) Mathematics Mini Games (2 years), the Netherlands (538) | This study investigated the effects of solving multiplication problems in online mini-games on the mathematical results of elementary school students. | 2nd and 3rd grade (78E, 327C) RCT, researcher-made 0.22 < 0.31(p < 0.05) |

| (Blanton et al., 2019) Early Algebra Learning Progression (6 months), the USA (535) | The aim was to investigate the effectiveness of an early algebra intervention with a heterogeneous student population. | 3rd grade (1637E, 1448C) RCT, researcher-made correctness: 0.80 > 0.09 (p < 0.01) |

| (Bodner & Coulson, 2021) ST Math (34 weeks), the USA (535) | The study was designed to provide empirical evidence of the effectiveness of the ST Math add-on software, in which students solve problems presented in a fun way and use virtual manipulatives. | 4th grade (2255E, 2395C) 5th grade (2226E, 2437C) RCT, standardized 4th grade: 0.06 < 0.07 (p < 0.00) 5th grade: 0.10 > 0.07 (p < 0.00) |

| (Brezovszky et al., 2019) Number Navigation Game (10 weeks), Finland (532) | The study tested the effectiveness of a game-based learning environment to strengthen the adaptive numerical knowledge of elementary school students. | 4th, 5th, and 6th grade (642E, 526C) RCT, researcher-made correct solutions, multi-op. solutions, and arithmetic fluency: 0.16 * > 0.15 (p < 0.05) |

| (Christopoulos et al., 2020) Exercise-based Learning Environment Eduten Playground (8 weeks), the United Arab Emirates (544) | The aim of the study was to investigate the extent to which curriculum-driven learning software improves students’ mathematical mastery and numeracy skills compared to the traditional didactic approach. | 3rd grade (65E, 70C) quasi-experiment, researcher-made 0.40 * < 0.43 (p = 0.02) |

| (Copeland et al., 2023; An et al., 2022; Bashkov, 2021) IXL Math (14 or 15 weeks), the USA (535) | The aim of the study was to determine the effects of the adaptive learning platform IXL Math on students’ mathematical performance. | grades 3–5 (263E, 282C) RCT, standardized 0.13 < 0.21 (p = 0.01) |

| (de Kock & Harskamp, 2014) A Metacognitive Computer Programme for Word Problem Solving (10 weeks), the Netherlands (538) | Investigating the effectiveness of a metacognitive computer program designed to help students in the problem-solving process by visualizing clues in the form of a staircase. | 5th grade (280E, 110C) quasi-experiment, researcher-made analyzing word problems: 0.26 * < 0.28 (p = 0.02), solving word problems: 0.29 * > 0.28 (p < 0.01) |

| (Delić-Zimić & Destović, 2019) Mathematical Modeling (18 weeks), Bosnia and Herzegovina (452) | The aim was to apply mathematical modeling in problem-based teaching and to demystify its role and importance in improving the educational effect. | 4th grade (52E, 214C) quasi-experiment, researcher-made 0.55 * > 0.39 (p < 0.01) |

| (Đokić, 2015) Realistic Mathematics Education (3 months), Serbia (508) | The aim was to test whether an innovative textbook based on Realistic Mathematics Education has a positive impact on students’ performance in geometry. | 4th grade, (73E, 75C) RCT, researcher-made 0.88 * > 0.41 (p < 0.01) |

| (Eddy et al., 2014; HMH, 2023) GO Math! (2 years), the USA (535) | The study evaluated the impact of GO Math! program, which is based on the common core state standards for mathematics, on student achievement. | grade 1–3 (1382E, 978C) RCT, standardized 0.50 > 0.10 (p < 0.01) |

| (Erol & Batdal Karaduman, 2018) Brain Based Learning (3 months), Turkey (523) | The aim was to investigate the effects of brain-based learning activities on the mathematical success of fourth graders. | 4th grade (46E, 45C) quasi-experiment, researcher-made 0.86 * > 0.53 (p < 0.01) |

| (Faber et al., 2017) A Digital Formative Assessment Tool: Snappet (5 months), the Netherlands (538) | The aim of the study was to investigate the effect of the digital tool Snappet, which enables formative feedback, on students’ mathematical performance. | 3rd grade (822E, 986C) RCT, standardized 0.43 * > 0.12 (p < 0.01) |

| (Fischer et al., 2019) Arithmetic Comprehension at Elementary School—ACE (1 year), France (485) | The aim of the study was to investigate the development of young students’ understanding of the mathematical concept of equality. | 2nd grade (1140E, 1155C) quasi-experiment, researcher-made 0.56 * > 0.10 (p = 0.00) |

| (Hall et al., 2020, 2022) Bridges in Mathematics (6 months), the USA (535) | The goal was to investigate the effectiveness of the student-centered and standards-based Bridges in Mathematics curriculum. | 5th grade (1,839E, 3,354C) quasi-experiment, standardized 0.25 > 0.07 (p = 0.00) |

| (Hassler Hallstedt et al., 2018) Mathematics Tablet Intervention for Low Performing Second Graders (20 weeks), Sweden (521) | The aim was to determine the effectiveness of a tablet intervention in improving the mathematical skills of students who initially showed a lower level of performance in mathematics. | 2nd grade (151E, 130C) RCT, standardized addition 0–12, subtraction 0–12, subtraction 0–18: 0.56 * > 0.30 (p = 0.00) |

| (Have et al., 2018) Physical Activity Improves Children’s Math Achievement (9 months), Denmark (525) | The aim of the study was to find out how the integration of physical activity into mathematics lessons can influence educational outcomes. | 1st grade (268E, 182C) RCT, standardized 0.38 > 0.24 (p = 0.01) |

| (Jaciw et al., 2016; HMH, 2017, 2020) Math in Focus (1 year), the USA (535) | The study evaluated the effectiveness of the Math in Focus program based on the teaching methods used in Singapore. | grade 3–5 (744E, 702C) RCT, standardized 0.15 > 0.13 (p = 0.05) |

| (Kutnick et al., 2017) Relation-Based Group Work Approach (7 months), Hong Kong—China (602) | This study examined whether the relational approach to group work, which focused on developing social relationships, communication, and cooperative problem solving, can improve students’ mathematical performance. | 3rd grade (319E, 185C) quasi-experiment, researcher-made 0.20 < 0.23 (p = 0.00) |

| (Lambert et al., 2014) Accelerated Math (1 year), the USA (535) | The aim was to evaluate the impact of a technology-based learning progress monitoring tool on student outcomes. | grade 2–5 (356E, 340C) RCT, standardized 0.47 * > 0.19 (p < 0.05) |

| (Lazić et al., 2021) Project Based Learning (3 months), Serbia (508) | The aim was to investigate the effectiveness of project-based learning in elementary school mathematics lessons. | 3rd grade (77E, 70K) quasi-experiment, researcher-made 1.04 * > 0.41 (p = 0.00) |

| (Lindorff et al., 2019) Inspire Maths (1 year), the UK (556) | The aim was to investigate the use of a mathematics textbook based on the Singapore elementary school teaching approach. | 1st grade (249E, 281C) RCT, standardized 0.42 > 0.22 (p < 0.05). |

| (Lowrie et al., 2017) Visuospatial reasoning (10 weeks), Australia (516) | The aim was to evaluate the effects of a visuospatial intervention program on students’ mathematical performance. | 6th grade (120E, 66C) quasi-experiment, researcher-made 0.40 > 0.38 (p < 0.02) |

| (Magistro et al., 2022) Physically Active Mathematics Lessons (2 years), Italy (515) | The aim was to investigate how the inclusion of physical activities in mathematics lessons affects students’ mathematical performance and gross motor skill development. | 1st and 2nd grade (36E, 46C) quasi-experiment, standardized arithmetic: 0.90 > 0.56 (p = 0.00) |

| (McDonald Connor et al., 2018), Individualizing student instruction in mathematics (ISI-Math) (6 months), the USA (535) | The aim was to investigate whether individualized mathematics lessons are more effective than non-individualized lessons. | 2nd grade (209E, 161C) RCT, standardized math fluency: 0.60 > 0.26 (p = 0.00) KeyMath: 0.41 > 0.26 (p = 0.00) |

| (McNeil et al., 2015) Modified Arithmetic Practice (12 weeks), the USA (535) | The aim was to investigate whether a modified version of arithmetic practice and workbooks can improve students’ understanding of mathematical equations. | 2nd grade (83E, 83C) quasi-experiment, researcher-made 0.37 < 0.39 (p = 0.00) |

| (Motteram et al., 2016) ReflectED Programme (28 weeks), the UK (556) | The aim was to evaluate the impact of the ReflectED metacognitive skills program on students’ academic outcomes in mathematics. | 5th grade (839E, 731C) RCT, standardized 0.30 > 0.13 (p = 0.05) |

| (Mullender-Wijnsma et al., 2015) Fit and Academically Proficient at School (2 years), the Netherlands (538) | The aim was to evaluate the effectiveness of integrating physical activity into mathematics education. | 2nd and 3rd grade (249E, 250C) RCT, standardized mathematics speed test: 0.51 * > 0.33 (p = 0.00) general mathematics: 0.42 * > 0.22 (p = 0.00) |

| (Murtagh et al., 2022) Playfulmaths! (6 months), Palestinian Authority (366*) | The aim was to investigate the relationship between learning through play and students’ performance in mathematics. | grade 1–4 (415E, 444C) quasi-experiment, researcher-made 0.09 * < 0.17 (p = 0.00) |

| (Pareto, 2014) The Teachable Agent Game (3 months), Sweden (521) | The study investigated how the interactive learning platform with a teachable agent can influence conceptual understanding and reasoning in mathematics. | grade 2–6 (154E, 129C) quasi-experiment, researcher-made 0.34 * > 0.30 (p = 0.00) |

| (Piper et al., 2016) Primary Math and Reading (PRIMR) Initiative (1 year), Kenya (NA) | The goal was to determine the impact of the PRIMR program, which provides students with learning materials and helps teachers with professional development, on students’ mathematical performance. | 1st and 2nd grade (3097E, 1166C) RCT, standardized/ procedural index: 1st grade: 0.20 > 0.09 (p = 0.03) 2nd grade: 0.37 > 0.09 (p = 0.00) conceptual index in 2nd grade: 0.33 > 0.09 (p < 0.01) |

| (Pitchford, 2015) Maths Tablet Intervention (8 weeks), Malawi (NA) | The study investigated the impact of using tablets to improve students’ performance in mathematics. | grade 1–3 (104E, 100C) RCT, researcher-made 0.32 < 0.35 (p < 0.05) |

| (Polotskaia & Savard, 2018; Savard & Polotskaia, 2017) Equilibrated Development Approach (3 years), Canada (512) | The aim was to investigate the effectiveness of the relational approach in solving additive word problems. | 2nd grade (216E, 196C) quasi-experiment, researcher-made 0.44 > 0.25 (p = 0.05) |

| (Pongsakdi et al., 2016) Word Problem Enrichment Program (WPE) (2 months), Finland (532) | The study investigated whether teacher-created word problems can help “improve student mathematical modeling and problem-solving skills” (p. 23) | 4th and 6th grade (97E, 70C) quasi-experiment, researcher-made word problem solving: 0.55 * > 0.39 (p = 0.00) application word problem: 0.28 * < 0.39 (p < 0.05) |

| (Schwarz, 2019) Symphony Math (1 year), the USA (535) | The aim was to determine the effectiveness of the intervention based on the web-enabled Symphony Math application. | grade 1–4 (579E, 624C) quasi-experiment, standardized 0.42 * > 0.14 (p = 0.00) |

| (Sharma & Singh, 2019) Interweaving Mathematics Pedagogy and Contents of Teaching (IMPACT) (6 months), India (337*) | The aim was to investigate the effectiveness of the IMPACT program using the mathematics toolkit. | 2nd grade (125E, 125C) quasi-experiment, researcher-made 1.27 * > 0.32 (p = 0.00) |

| (Sides & Cuevas, 2020) Student Goal Setting (8 weeks), the USA (535) | The aim of the study was to investigate whether setting goals can motivate students to learn and improve their self-efficacy and performance in mathematics. | 3rd and 4th grade (37E, 33C) quasi-experiment, researcher-made 1.59 * > 0.60 (p = 0.00) |

| (Solomon et al., 2019) JUMP Math program (6 months), Canada (512) | The aim of the study was to determine whether the JUMP Math program, which is based on findings documented in the scientific literature, leads to students’ better performance in mathematics. | 2nd grade (350E, 204C) 5th grade (348 E, 244C) RCT, standardized 2nd grade: 0.26 > 0.22 (p < 0.01), 5th grade: 0.22 > 0.21 (p = 0.04) |

| (Vazou & Skrade, 2017) Move for Thought (8 weeks), the USA (535) | The aim was to investigate whether integrating physical activity into mathematics lessons would improve students’ mathematical performance. | 4th and 5th grade (107E, 118C) quasi-experiment, standardized 0.55 * > 0.33 (p = 0.00) |

| (Veldhuis & van den Heuvel-Panhuizen, 2020) Classroom Assessment Techniques (CATs) (6 months), the Netherlands (538) | The aim was to investigate the effects of teachers’ assessment methods in the classroom on students’ performance in mathematics. | 3rd grade (207E, 99C) RCT, standardized 0.13 < 0.30 (p = 0.04) |

| (Worth et al., 2015) Mathematics and Reasoning (10 to 12 weeks), the UK (556) | The aim was to determine the effectiveness of the intervention aimed at developing children’s understanding of the logical principles of mathematics. | 2nd grade (517E, 848C) RCT, standardized 0.20 > 0.14 (p = 0.05) |

| (Yeh et al., 2019) Math Island (2 years), Taiwan (599) | The aim was to investigate the effects of the online game Math Island on students’ mathematical performance. | 2nd and 3rd grade (209E, 125C) quasi-experiment, standardized 0.48 * > 0.28 (p < 0.05) |

| (Zahedi et al., 2023) Blended Learning (3 years) India (337 *) | The aim of the study was to evaluate blended learning in mathematics education using a platform for adaptive digital online content. | 2nd grade, (108E, 113C) quasi-experiment, researcher-made 0.34 = 0.34, (p < 0.05) |

References

- Al-Mashaqbeh, I. (2016). IPad in elementary school math learning setting. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning, 11(2), 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Almeida, L. M. W. D., & Castro, É. M. V. d. (2023). Metacognitive strategies in mathematical modelling activities: Structuring an identification instrument. Journal of Research in Mathematics Education, 12(3), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, X., Schonberg, C., & Bashkov, B. M. (2022). IXL implementation fidelity and usage recommendations. In Online submission. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED629011 (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Anthony, G., & Walshaw, M. (2007). Effective pedagogy in mathematics/Pàngarau best evidence synthesis iteration [BES]. New Zealand Ministry of Education. Available online: https://thehub.sia.govt.nz/assets/documents/42433_BES_Maths07_Complete_0.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Anthony, G., & Walshaw, M. (2009). Effective pedagogy in mathematics. UNESCO International Bureau of Education. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED540738 (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Apugliese, A., & Lewis, S. E. (2017). Impact of instructional decisions on the effectiveness of cooperative learning in chemistry through meta-analysis. Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 18(1), 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araya, R., & Diaz, K. (2020). Implementing government elementary math exercises online: Positive effects found in RCT under social turmoil in Chile. Education Sciences, 10(9), 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Astleitner, H. (2020). Foreword. In H. Astleitner (Ed.), Intervention research in educational practice alternative theoretical frameworks and application problems (pp. 7–16). Waxmann. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babić, T., Kolar, L., & Miličević, M. (2021, 27 September–1 October). Individual, cooperative and collaborative learning and students’ perceptions of their impact on their own study performance. 2021 44th International Convention on Information, Communication and Electronic Technology (MIPRO) (pp. 864–869), Opatija, Croatia. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakar, M. A. A., & Ismail, N. (2020). Metacognitive learning strategies in mathematics classroom intervention: A review of implementation and operational design aspect. International Electronic Journal of Mathematics Education, 15(1), 5937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A., Cai, J., English, L., Kaiser, G., Mesa, V., & Van Dooren, W. (2019). Beyond small, medium, or large: Points of consideration when interpreting effect sizes. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 102(1), 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, M., Van Den Heuvel-Panhuizen, M., & Robitzsch, A. (2015). Effects of playing mathematics computer games on primary school students’ multiplicative reasoning ability. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 40, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcelos, T., Muñoz-Soto, R., Villarroel, R., Merino, E., & Silveira, I. (2018). Mathematics learning through computational thinking activities: A systematic literature review. JUCS—Journal of Universal Computer Science, 24(7), 815–845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartlett, J., & Charles, S. (2022). Power to the people: A Beginner’s tutorial to power analysis using jamovi. Meta-Psychology, 6, 3078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartolini, M. G., & Martignone, F. (2020). Manipulatives in mathematics education. In S. Lerman (Ed.), Encyclopedia of mathematics education (pp. 487–494). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashkov, B. M. (2021). Assessing the impact of IXL Math over three years: A quasi-experimental study. IXL Learning. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED628125 (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Bendixen, L. D. (2016). Teaching for epistemic change in elementary classrooms. In J. A. Greene, W. A. Sandoval, & I. Bråten (Eds.), Handbook of epistemic cognition (pp. 281–299). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Blanton, M., Stroud, R., Stephens, A., Gardiner, A., Stylianou, D., Knuth, E., Isler-Baykal, I., & Strachota, S. (2019). Does early algebra matter? The effectiveness of an early algebra intervention in grades 3 to 5. American Educational Research Journal, 56(5), 1930–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodner, M., & Coulson, A. (2021). Randomized trial of elementary school ST Math software intervention reveals significant efficacy. MIND Research Institute. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED616922 (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Bognar, L., & Matijević, M. (2005). Didaktika [Didactics]. Školska knjiga. [Google Scholar]

- Bonwell, C. C., & Eison, J. A. (1991). Active learning: Creating excitement in the classroom (No. 1; ASHE-ERIC higher education reports). The George Washington University, School of Education and Human Development. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED336049 (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. T., & Rothstein, H. R. (2021). Introduction to meta-analysis (2nd ed.). Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, C. W. (2000). A quantitative literature review of cooperative learning effects on high school and college chemistry achievement. Journal of Chemical Education, 77(1), 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, B., Bremser, P., Duval, A. M., Lockwood, E., & White, D. (2017). What does active learning mean for mathematicians? Notices of the American Mathematical Society, 64(2), 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brezovszky, B., McMullen, J., Veermans, K., Hannula-Sormunen, M. M., Rodríguez-Aflecht, G., Pongsakdi, N., Laakkonen, E., & Lehtinen, E. (2019). Effects of a mathematics game-based learning environment on primary school students’ adaptive number knowledge. Computers & Education, 128, 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruner, J. S. (1964). The course of cognitive growth. American Psychologist, 19(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruner, J. S. (1977). The process of education. Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bruner, J. S., & Kenney, H. J. (1965). Representation and mathematics learning. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 30(1), 50–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J. (2022). What research says about teaching mathematics through problem posing. Éducation et Didactique, 16, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbonneau, K. J., Marley, S. C., & Selig, J. P. (2013). A meta-analysis of the efficacy of teaching mathematics with concrete manipulatives. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105(2), 380–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, A. C. K., & Slavin, R. E. (2013). The effectiveness of educational technology applications for enhancing mathematics achievement in K-12 classrooms: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 9, 88–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, A. C. K., & Slavin, R. E. (2016). How methodological features affect effect sizes in education. Educational Researcher, 45(5), 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopoulos, A., Kajasilta, H., Salakoski, T., & Laakso, M. -J. (2020). Limits and virtues of educational technology in elementary school mathematics. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 49(1), 59–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chwo, G. S. M., Marek, M. W., & Wu, W. -C. V. (2018). Meta-analysis of MALL research and design. System, 74, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, S., Cook, M., Grant, A., & Ross, S. (2023). Randomized-control efficacy study of IXL math in holland public schools. Center for Research and Reform in Education. Available online: https://jscholarship.library.jhu.edu/handle/1774.2/69038 (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Corporation for Digital Scholarship. (2024). Zotero (Version 7.0.10) [Computer software]. Available online: https://www.zotero.org/ (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (3rd ed.). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- de Kock, W., & Harskamp, E. (2014). Can teachers in primary education implement a metacognitive computer programme for word problem solving in their mathematics classes? Educational Research and Evaluation, 20(3), 231–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delić-Zimić, A., & Destović, F. (2019). Mathematical modeling and statistical representation of experimental access. In S. Avdaković (Ed.), Advanced technologies, systems, and applications III: Proceedings of the international Symposium on innovative and interdisciplinary applications of advanced technologies (IAT) (Vol. 1, pp. 36–48). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dienes, Z. P. (2007). Some thoughts on the dynamics of learning mathematics. In B. Sriraman (Ed.), Zoltan Paul Dienes and the dynamics of mathematical learning (pp. 1–118). University of Montana Press. Available online: https://www.zoltandienes.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/ZPD_and_Dynamics_of_Math_Learning-Monograph2_2007.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Đokić, O. J. (2015). The effects of RME and innovative textbook model on 4th grade pupils’ reasoning in geometry. In J. Novotná, & H. Moraová (Eds.), Proceedings: Developing mathematical language and reasoning (pp. 107–117). Charles University, Faculty of Education. Available online: https://www.semt.cz/proceedings/semt-15.pdf#page=108 (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Eddy, R. M., Hankel, N., Goldman, A., & Murphy, K. (2014). Houghton mifflin harcourt GO math! Efficacy study year two final report. Cobblestone Applied Research & Evaluation, Inc. Available online: https://s3.amazonaws.com/prod-hmhco-vmg-craftcms-public/research/HMH_GoMath_RCT_1_3_Final_Report_2014.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Erol, M., & Batdal Karaduman, G. (2018). The effect of activities congruent with brain based learning model on students’ mathematical achievement. NeuroQuantology, 16(5), 13–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evidence for Policy & Practice Information (EPPI) Centre. (2024). EPPI-reviewer (Version 6.15.5.0); [Online app]. Available online: https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Default.aspx?alias=eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/er4 (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Faber, J. M., Luyten, H., & Visscher, A. J. (2017). The effects of a digital formative assessment tool on mathematics achievement and student motivation: Results of a randomized experiment. Computers & Education, 106, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A. -G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A. -G., & Buchner, A. (2007). GPower 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, Behavioral and Biomedical sciences, Beh. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, J. -P., Sander, E., Sensevy, G., Vilette, B., & Richard, J. -F. (2019). Can young students understand the mathematical concept of equality? A whole-year arithmetic teaching experiment in second grade. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 34(2), 439–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, S., Eddy, S. L., McDonough, M., Smith, M. K., Okoroafor, N., Jordt, H., & Wenderoth, M. P. (2014). Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(23), 8410–8415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glatthorn, A. A., Boschee, F. A., Whitehead, B. M., & Boschee, B. F. (2019). Curriculum leadership: Strategies for development and implementation (5th ed.). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Hadie, S. N. H. (2024). ABC of a scoping review: A simplified JBI scoping review guideline. Education in Medicine Journal, 16(2), 185–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, L., & Yasmadi, B. (2021). Conceptual and procedural knowledge in mathematics education. Design Engineering, 9, 1271–1280. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, G. J., Schaefer, P., Hedges, T., & Grodsky, E. (2020). Examining Bridges in Mathematics and differential effects among English language learners. Madison Education Partnership. Available online: https://mep.wceruw.org/documents/MEP-MEMO-Bridges.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Hall, G. J., Schaefer, P., Hedges, T., & Grodsky, E. (2022). Examining bridges in mathematics and differential effects among english language learners. School Psychology Review, 51(4), 392–405. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/2372966X.2020.1871304 (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Hassler Hallstedt, M., Klingberg, T., & Ghaderi, A. (2018). Short and long-term effects of a mathematics tablet intervention for low performing second graders. Journal of Educational Psychology, 110(8), 1127–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Have, M., Nielsen, J. H., Ernst, M. T., Gejl, A. K., Fredens, K., Grøntved, A., & Kristensen, P. L. (2018). Classroom-based physical activity improves children’s math achievement—A randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE, 13(12), e0208787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heinrich-Heine-Hochschule Düsseldorf. (2020, February 21). G*Power: Statistical power analyses for Mac and Windows (Version 3.1.9.7) [Computer software]. Available online: https://www.psychologie.hhu.de/arbeitsgruppen/allgemeine-psychologie-und-arbeitspsychologie/gpower (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Higgins, K., Huscroft-D’Angelo, J., & Crawford, L. (2019). Effects of technology in mathematics on achievement, motivation, and attitude: A meta-analysis. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 57(2), 283–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (HMH). (2017). Math in focus: Elementary grades efficacy study (No. 526);Educational Research Institute of America. Available online: https://s3.amazonaws.com/prod-hmhco-vmg-craftcms-public/research/HMH_Math_in_Focus_RM_3-5_2017SY_Update.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (HMH). (2020). Math in focus: Singapore math by marshall cavendish: Evidence base. Available online: https://s3.amazonaws.com/prod-hmhco-vmg-craftcms-public/research/Math-In-Focus-2020-Foundations-Paper-LR.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Houghton Mifflin Harcourt (HMH). (2023). Go Math!: Research evidence base. Available online: https://s3.amazonaws.com/prod-hmhco-vmg-craftcms-public/documents/HMH-Go-Math-Evidence-Base-Final.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Hull, D. M., Hinerman, K. M., Ferguson, S. L., Chen, Q., & Näslund-Hadley, E. I. (2018). Teacher-led math inquiry: A cluster randomized trial in Belize. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 40(3), 336–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jablonka, E. (2003). Mathematical Literacy. In A. J. Bishop, M. A. Clements, C. Keitel, J. Kilpatrick, & F. K. S. Leung (Eds.), Second international handbook of mathematics education (pp. 75–102). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaciw, A. P., Hegseth, W. M., Lin, L., Toby, M., Newman, D., Ma, B., & Zacamy, J. (2016). Assessing impacts of Math in Focus, a “Singapore Math” program. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 9(4), 473–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, J. E., & Paris, S. G. (1987). Children’s metacognition about reading: Issues in definition, measurement, and instruction. Educational Psychologist, 22(3–4), 255–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobse, A. E., & Harskamp, E. G. (2011). A meta-analysis of the effects of instructional interventions on students’ mathematics achievement. GION, Gronings Instituut voor Onderzoek van Onderwijs, Opvoeding en Ontwikkeling, Rijksuniversiteit Groningen. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/11370/1a0ea36d-3ca3-4639-9bb4-6fa220e50f38 (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Kersaint, G. (2015). Orchestrating mathematical discourse to enhance student learning: Creating successful classroom environments where every student participates in rigorous discussions. Curriculum Associates. Available online: https://www.curriculumassociates.com/programs/i-ready-learning/classroom-math/orchestrating-mathematical-discourse-whitepaper (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Kingston, N., & Nash, B. (2011). Formative assessment: A meta-analysis and a call for research. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 30(4), 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kul, Ü., & Çelik, S. (2020). A meta-analysis of the impact of problem posing strategies on students’ learning of mathematics. Revista Romaneasca Pentru Educatie Multidimensionala, 12(3), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutnick, P., Fung, D., Mok, I., Leung, F., Li, J., Lee, B., & Lai, V. (2017). Implementing effective group work for mathematical achievement in primary school classrooms in Hong Kong. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 15(5), 957–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyndt, E., Raes, E., Lismont, B., Timmers, F., Cascallar, E., & Dochy, F. (2013). A meta-analysis of the effects of face-to-face cooperative learning. Do recent studies falsify or verify earlier findings? Educational Research Review, 10, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakens, D. (2013). Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: A practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 00863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, R., Algozzine, B., & Gee, J. M. (2014). Effects of progress monitoring on math performance of at-risk students. Journal of Education, Society and Behavioural Science, 4, 527–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laski, E. V., Jor’dan, J. R., Daoust, C., & Murray, A. K. (2015). What makes mathematics manipulatives effective? Lessons from cognitive science and montessori education. SAGE Open, 5(2), 2158244015589588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazić, B. D., Knezević, J. B., & Maričić, S. M. (2021). The influence of project-based learning on student achievement in elementary mathematics education. South African Journal of Education, 41(3), 1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenhard, W., & Lenhard, A. (2022). Computation of effect sizes [Online app]. Available online: https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.17823.92329 (accessed on 29 December 2024).

- Li, Q., & Ma, X. (2010). A meta-analysis of the effects of computer technology on school students’ mathematics learning. Educational Psychology Review, 22(3), 215–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindorff, A. M., Hall, J., & Sammons, P. (2019). Investigating a Singapore-based mathematics textbook and teaching approach in classrooms in England. Frontiers in Education, 4, 00037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipsey, M. W., Puzio, K., Yun, C., Hebert, M. A., Steinka-Fry, K., Cole, M. W., Roberts, M., Anthony, K. S., & Busick, M. D. (2012). Translating the statistical representation of the effects of education interventions into more readily interpretable forms (No. NCSER 2013-3000). National Center for Special Education Research, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Available online: https://ies.ed.gov/ncser/pubs/20133000/pdf/20133000.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Lowrie, T., Logan, T., & Ramful, A. (2017). Visuospatial training improves elementary students’ mathematics performance. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 87(2), 170–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucangeli, D., Fastame, M. C., Pedron, M., Porru, A., Duca, V., Hitchcott, P. K., & Penna, M. P. (2019). Metacognition and errors: The impact of self-regulatory trainings in children with specific learning disabilities. ZDM, 51(4), 577–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magistro, D., Cooper, S. B., Carlevaro, F., Marchetti, I., Magno, F., Bardaglio, G., & Musella, G. (2022). Two years of physically active mathematics lessons enhance cognitive function and gross motor skills in primary school children. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 63, 102254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R. E. (2002). Cognitive theory and the design of multimedia instruction: An example of the two-way street between cognition and instruction. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2002(89), 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald Connor, C., Mazzocco, M. M. M., Kurz, T., Crowe, E. C., Tighe, E. L., Wood, T. S., & Morrison, F. J. (2018). Using assessment to individualize early mathematics instruction. Journal of School Psychology, 66, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNeil, N. M., Fyfe, E. R., & Dunwiddie, A. E. (2015). Arithmetic practice can be modified to promote understanding of mathematical equivalence. Journal of Educational Psychology, 107(2), 423–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeil, N. M., Hornburg, C. B., Brletic-Shipley, H., & Matthews, J. M. (2019). Improving children’s understanding of mathematical equivalence via an intervention that goes beyond nontraditional arithmetic practice. Journal of Educational Psychology, 111(6), 1023–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (3rd ed.). SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Motteram, G., Choudry, S., Kalambouka, A., Hutcheson, G., & Barton, H. (2016). ReflectED: Evaluation report and executive summary. Education Endowment Foundation. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED581262 (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Moyer-Packenham, P. S., & Westenskow, A. (2013). Effects of virtual manipulatives on student achievement and mathematics learning. International Journal of Virtual and Personal Learning Environments (IJVPLE), 4(3), 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mullender-Wijnsma, M. J., Hartman, E., de Greeff, J. W., Bosker, R. J., Doolaard, S., & Visscher, C. (2015). Improving academic performance of school-age children by physical activity in the classroom: 1-year program evaluation. Journal of School Health, 85(6), 365–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z., Pollock, D., Khalil, H., Alexander, L., Mclnerney, P., Godfrey, C. M., Peters, M., & Tricco, A. C. (2022). What are scoping reviews? Providing a formal definition of scoping reviews as a type of evidence synthesis. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 20(4), 950–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murtagh, E., Sawalma, J., & Martin, R. (2022). Playful maths! The influence of play-based learning on academic performance of Palestinian primary school children. Educational Research for Policy and Practice, 21(3), 407–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musna, R. R., Juandi, D., & Jupri, A. (2021). A meta-analysis study of the effect of Problem-Based Learning model on students’ mathematical problem solving skills. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1882(1), 012090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mužar Horvat, S. (2024). Značajke učinkovite početne nastave matematike: Sustavni pregled literature [Features of effective elementary mathematics instruction: A systematic literature review]. Marsonia: Časopis za društvena i humanistička istraživanja, 3(1), 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- Myers, J. A., Witzel, B. S., Powell, S. R., Li, H., Pigott, T. D., Xin, Y. P., & Hughes, E. M. (2022). A meta-analysis of mathematics word-problem solving interventions for elementary students who evidence mathematics difficulties. Review of Educational Research, 92(5), 695–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM). (2000). Principles and standards for school mathematics. National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. [Google Scholar]

- National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM). (2014). Principles to actions: Ensuring mathematical success for all. National Council of Teachers of Mathematics. [Google Scholar]

- Odani, A. O., & Orongan, R. C. (2020). Critical thinking, mathematical dispositions, and metacognitive awareness of students: A causal model on performance. International Journal of Science and Research, 10(7), 698–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odum, M., Meaney, K. S., & Knudson, D. V. (2021). Active learning classroom design and student engagement: An exploratory study. Journal of Learning Spaces, 10(1), 27–41. Available online: https://libjournal.uncg.edu/jls/article/view/2102 (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- OECD. (2023). PISA 2022 assessment and analytical framework. PISA, OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, R., Shahrill, M., Mohd Roslan, R., Nurhasanah, F., Zakir, N., & Asamoah, D. (2022). The questioning techniques of primary school mathematics teachers in their journey to incorporate dialogic teaching. Southeast Asian Mathematics Education Journal, 12(2), 125–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., & Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5(1), 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pareto, L. (2014). A teachable agent game engaging primary school children to learn arithmetic concepts and reasoning. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 24(3), 251–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellegrini, M., Lake, C., Inns, A., & Slavin, R. E. (2018). Effective programs in elementary mathematics: A best-evidence synthesis [Best Evidence Encyclopedia]. Johns Hopkins University School of Education’s Center for Research and Reform in Education (CRRE). Available online: http://173.213.237.113/word/elem_math_Oct_8_2018.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Pellegrini, M., Lake, C., Neitzel, A., & Slavin, R. E. (2021). Effective programs in elementary mathematics: A meta-analysis. AERA Open, 7, 2332858420986211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perugini, M., Gallucci, M., & Costantini, G. (2018). A practical primer to power analysis for simple experimental designs. International Review of Social Psychology, 31(1), 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M. D. J., Marnie, C., Tricco, A. C., Pollock, D., Munn, Z., Alexander, L., McInerney, P., Godfrey, C. M., & Khalil, H. (2020). Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 18(10), 2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piaget, J. (2003). The psychology of intelligence (M. Piercy, & D. E. Berlyne, Trans.). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Piper, B., Ralaingita, W., Akach, L., & King, S. (2016). Improving procedural and conceptual mathematics outcomes: Evidence from a randomised controlled trial in Kenya. Journal of Development Effectiveness, 8(3), 404–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitchford, N. J. (2015). Development of early mathematical skills with a tablet intervention: A randomized control trial in Malawi. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polotskaia, E., & Savard, A. (2018). Using the relational paradigm: Effects on pupils’ reasoning in solving additive word problems. Research in Mathematics Education, 20(1), 70–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polya, G. (1988). How to solve it: A new aspect of mathematical method (2nd ed.). Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pongsakdi, N., Laine, T., Veermans, K., Hannula-Sormunen, M. M., & Lehtinen, E. (2016). Improving word problem performance in elementary school students by enriching word problems used in mathematics teaching. Nordic Studies in Mathematics Education, 21(2), 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prediger, S., Götze, D., Holzäpfel, L., Rösken-Winter, B., & Selter, C. (2022). Five principles for high-quality mathematics teaching: Combining normative, epistemological, empirical, and pragmatic perspectives for specifying the content of professional development. Frontiers in Education, 7, 969212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putra, R. W. Y., Sunyono, S., Haenilah, E. Y., Hariri, H., Sutiarso, S., Nurhanurawati, N., & Supriadi, N. (2023). Systematic literature review on the recent three-year trend mathematical representation ability in scopus database. Infinity Journal, 12(2), 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rittle-Johnson, B. (2019). Iterative development of conceptual and procedural knowledge in mathematics learning and instruction. In J. Dunlosky, & K. A. Rawson (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of cognition and education (pp. 124–147). Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rösken, B., & Rolka, K. (2006). A picture is worth a 1000 words—The role of visualization in mathematics learning. In Proceedings 30th Conference of the International Group for the Psychology of Mathematics Education (Vol. 4, pp. 457–464). Charles University in Prague, Faculty of Education. [Google Scholar]

- Salam, M., Misu, L., Rahim, U., Hindaryatiningsih, N., & Ghani, A. (2020). Strategies of metacognition based on behavioural learning to improve metacognition awareness and mathematics ability of students. International Journal of Instruction, 13(2), 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sargeant, J. M., & O’Connor, A. M. (2020). Scoping reviews, systematic reviews, and meta-analysis: Applications in veterinary medicine. Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 7, 00011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savard, A., & Polotskaia, E. (2017). Who’s wrong? Tasks fostering understanding of mathematical relationships in word problems in elementary students. ZDM, 49(6), 823–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, W. H., Cogan, L. S., & McKnight, C. C. (2011). Equality of educational opportunity: Myth or reality in U.S. schooling? American Educator, 34(4), 12–19. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ909927 (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Schnepel, S., & Aunio, P. (2022). A systematic review of mathematics interventions for primary school students with intellectual disabilities. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 37(4), 663–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenherr, J., Strohmaier, A. R., & Schukajlow, S. (2024). Learning with visualizations helps: A meta-analysis of visualization interventions in mathematics education. Educational Research Review, 45, 100639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schraw, G. (1998). Promoting general metacognitive awareness. Instructional Science, 26(1), 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarz, P. (2019). Raising the bar district-wide using Symphony Math. Symphony Learning. Available online: https://content.symphonylearning.com/assets/web/SLC_Graves_2020_02_27.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Sercenia, J. C., & Prudente, M. S. (2023). Effectiveness of the metacognitive-based pedagogical intervention on mathematics achievement: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Instruction, 16(4), 561–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A., & Singh, S. (2019). IMPACT: Interweaving mathematics pedagogy and content of teaching-at elementary level. International Journal of Advance and Innovative Research, 5(4), 13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Sides, J. D., & Cuevas, J. A. (2020). Effect of goal setting for motivation, self-efficacy, and performance in elementary mathematics. International Journal of Instruction, 13(4), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simms, V., McKeaveney, C., Sloan, S., & Gilmore, C. (2019). Interventions to improve mathematical achievement in primary school-aged children. Nuffield Foundation. Available online: https://pure.ulster.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/76895050/Math_interventions.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Slavin, R. E. (1986). Best-evidence synthesis: An alternative to meta-analytic and traditional reviews. Educational Researcher, 15(9), 5–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slavin, R. E. (1995). Best evidence synthesis: An intelligent alternative to meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 48(1), 9–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Slavin, R. E., & Lake, C. (2008). Effective programs in elementary mathematics: A best-evidence synthesis. Review of Educational Research, 78(3), 427–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snilstveit, B., Stevenson, J., Menon, R., Phillips, D., Gallagher, E., Geleen, M., Stamp, M., Jobse, H., Schmidt, T., & Jimenez, E. (2015). The impact of education programmes on learning and school participation in low-and middle-income countries. International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolowski, A. (2018). The effects of using representations in elementary mathematics: Meta-analysis of research. The International Academic Forum (IAFOR), 6(3), 129–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, T., Dupuis, A., O’Hara, A., Hockenberry, M. -N., Lam, J., Goco, G., Ferguson, B., & Tannock, R. (2019). A cluster-randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of the JUMP math program of math instruction for improving elementary math achievement. PLoS ONE, 14(10), e0223049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sortwell, A., Trimble, K., Ferraz, R., Geelan, D. R., Hine, G., Ramirez-Campillo, R., Carter-Thuiller, B., Gkintoni, E., & Xuan, Q. (2024). A systematic review of meta-analyses on the impact of formative assessment on K-12 students’ learning: Toward sustainable quality education. Sustainability, 16(17), 7826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springer, L., Stanne, M. E., & Donovan, S. S. (1999). Effects of small-group learning on undergraduates in science, mathematics, engineering, and technology: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 69(1), 21–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svane, R. P., Willemsen, M. M., Bleses, D., Krøjgaard, P., Verner, M., & Nielsen, H. S. (2023). A systematic literature review of math interventions across educational settings from early childhood education to high school. Frontiers in Education, 8, 1229849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takele, M. H. (2020). Implementation of active learning methods in mathematics classes of Woliso town primary schools, Ethiopia. International Journal of Science and Technology Education Research, 11(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Ting, F. S. T., Shroff, R. H., Lam, W. H., Garcia, R. C. C., Chan, C. L., Tsang, W. K., & Ezeamuzie, N. O. (2023). A meta-analysis of studies on the effects of active learning on Asian students’ performance in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) subjects. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 32(3), 379–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toit, S. d., & Kotze, G. (2009). Metacognitive strategies in the teaching and learning of mathematics. Pythagoras, 70, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). (2024). Breaking the gridlock: Reimagining cooperation in a polarized world. Available online: https://hdr.undp.org/system/files/documents/global-report-document/hdr2023-24reporten.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Vale, I., & Barbosa, A. (2023). Active learning strategies for an effective mathematics teaching and learning. European Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 11(3), 573–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazou, S., & Skrade, M. A. B. (2017). Intervention integrating physical activity with math: Math performance, perceived competence, and need satisfaction†. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 15(5), 508–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veldhuis, M., & van den Heuvel-Panhuizen, M. (2020). Supporting primary school teachers’ classroom assessment in mathematics education: Effects on student achievement. Mathematics Education Research Journal, 32(3), 449–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verschaffel, L., De Corte, E., Lasure, S., Van Vaerenbergh, G., Bogaerts, H., & Ratinckx, E. (1999). Learning to solve mathematical application problems: A design experiment with fifth graders. Mathematical Thinking and Learning, 1(3), 195–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, B. D. (2023). Practical meta-analysis effect size calculator (Version 2023.11.27) [Online app]. Campbell Collaboration. Available online: https://www.campbellcollaboration.org/calculator/ (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Worth, J., Sizmur, J., Ager, R., & Styles, B. (2015). Improving numeracy and literacy: Evaluation report and executive summary. Education Endowment Foundation. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED581142 (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Yeh, C., Cheng, H., Chen, Z., Liao, C., & Chan, T. (2019). Enhancing achievement and interest in mathematics learning through Math-Island. Research and Practice in Technology Enhanced Learning, 14(1), 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahedi, S., Bryant, C., Iyer, A., & Jaffer, R. (2023). The use of blended learning to promote learner-centered pedagogy in elementary math classrooms. Educational Research for Policy and Practice, 22(3), 389–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L., Stylianides, G. J., & Stylianides, A. J. (2024). Enhancing mathematical problem posing competence: A meta-analysis of intervention studies. International Journal of STEM Education, 11(1), 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria |

|---|---|

| 1. The study involves elementary school students from 1st to 5th grade, including 6th grade if it is part of elementary school. | 1. The study involves preschool children, secondary school students, or college students. |

| 2. Experimental research focuses on improving students’ outcomes in elementary mathematics. | 2. Experiments without a control group, non-experimental research, or studies that do not focus on students’ mathematical performance. |

| 3. The mathematical intervention program conducted in experimental classrooms is described in detail. | 3. Insufficient information about the mathematics intervention program, the intervention had nothing to do with elementary mathematics teaching, or it was conducted out of classroom context (e.g., in laboratory). |

| 4. At least two primary school teachers were involved in conducting the lessons and 30 students took part in the intervention and control group. | 4. There is only one elementary school teacher in the experimental and control groups, or the lessons are conducted by researchers or individuals associated with the research. 5. There is no control group in which the lessons are conducted as usual. 6. The student sample is smaller than 30 in one or both groups. |

| 5. The study includes quantitative results of the pupils’ mathematical performance from pretests (where the difference between the control and the experimental group is not greater than 25% of the standard deviation) and posttests, from which the effect size can be calculated or has already been calculated. | 7. The research includes only qualitative data or quantitative data from which the effect size cannot be calculated. 8. A pretest was not performed. 9. The difference between the control and the experimental group at baseline is greater than 25% of the standard deviation. |

| 6. Performance was measured using a general mathematics test that was fair to both the experimental and control groups. | 10. The instrument does not measure general mathematical performance, or it is biased toward the intervention group. |

| 7. The study showed a positive and statistically significant (p ≤ 0.05) effect size. | 11. There is no positive effect size, or it is not statistically significant (p > 0.05). |

| 8. Interventions lasted at least 8 weeks. | 12. Interventions lasted less than 8 weeks. |

| 9. The research was published between 2014 and 2023. | 13. The research was published before 2014 or after 2023. |

| 10. The study must be available in English, regardless of the country in which it was conducted. | 14. The research is not written in English. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bognar, B.; Mužar Horvat, S.; Jukić Matić, L. Characteristics of Effective Elementary Mathematics Instruction: A Scoping Review of Experimental Studies. Educ. Sci. 2025, 15, 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15010076

Bognar B, Mužar Horvat S, Jukić Matić L. Characteristics of Effective Elementary Mathematics Instruction: A Scoping Review of Experimental Studies. Education Sciences. 2025; 15(1):76. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15010076

Chicago/Turabian StyleBognar, Branko, Sanela Mužar Horvat, and Ljerka Jukić Matić. 2025. "Characteristics of Effective Elementary Mathematics Instruction: A Scoping Review of Experimental Studies" Education Sciences 15, no. 1: 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15010076

APA StyleBognar, B., Mužar Horvat, S., & Jukić Matić, L. (2025). Characteristics of Effective Elementary Mathematics Instruction: A Scoping Review of Experimental Studies. Education Sciences, 15(1), 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15010076