1. Introduction: Linguistic Variation and Discrimination

In some areas of the United States, fewer high school students are enrolling in post secondary education (

Edge & Silverman, 2024) for a number of reasons including increasing tuition and a public discourse suggesting college degrees are not practical. The decrease in enrollment is especially noticeable at regional public universities (

Gardner, 2023). It is also well documented that students who feel like they belong are more likely to persist in higher education (e.g.,

Gopalan & Brady, 2019;

O’Keeffe, 2013). Students of color and students who are the first generation in their families to attend college are more at risk of withdrawing from higher education, in part because they feel they do not belong there. These groups of students are also more likely to speak a language other than English or a non-standard variety at home and may have less exposure to the norms of language required in many higher education institutions (

Smitherman, 2017;

Tomé Lourido, 2024;

Zhang-Wu, 2022). Thus, it is possible that one reason for students dropping out of college or not even enrolling in higher education in the first place may be attitudes (real or perceived) toward the languages and dialects of these (potential) college students.

Unfortunately, linguistic diversity is not a category that is tracked by our own institution nor is it considered in federal reports made about diversity in higher education (

U.S. Department of Education, 2016). Many institutions of higher education in the U.S., including our own, (Portland State University, a public university in the Northwest US), operate with the tacit understanding that the language of teaching and learning (except for language study) will be English. More specifically, it will be the so-called ‘Standard American English’ variety (

McNair & Garrison-Fletcher, 2022). However, it is not well known outside of linguistics that ‘Standard American English’ (SAE) is not only difficult to define (

Preston, 2005) but also that its establishment and use rest on a foundation of racial and class discrimination (

Charity Hudley et al., 2020;

Kundnani, 2023).

Standard American English (SAE) is only one variety of the named language, English, that is derived from the patterns of English-speaking, white European Americans with high levels of education and social capital (

Baker-Bell, 2020). The variety was codified in dictionaries and style manuals as it separated from what was considered the standard variety in Great Britain (

Tieken-Boon van Ostade, 2009). We find it helpful to call SAE the ‘standard

dialect of American English’ to reinforce that it is not ‘proper English’ but one of many varieties of English, each capable of fully expressing the communication needs and desires of one or more speech communities.

There is no agreed upon objective label for this recognized variety of English and so we continue to use standard (SAE) to refer to the variety of language seen in academic papers and heard in the lecture hall. The implicit power of this racialized language variety (

Flores & Rosa, 2015), together with the idea that ‘standard’ English is the sole acceptable language variety in higher education, reflects an often-unacknowledged ideology that fosters and promotes linguistic bias and linguistic discrimination. This ‘standard language ideology’ (SLI) (

Curzan et al., 2023) is embedded within two common myths about language in the USA: (1) that the USA is a monolingual country and (2) that SAE is ‘better’ or ‘correct’ while other varieties are error-ridden versions of the standard language and are, following this myth, justly stigmatized. SLI arises out of the general public’s misunderstanding of the inherent variability in language and ignorance of the systematicity and complexity of all language varieties. It achieves its durability from the prioritization of written language in educational institutions where a prescriptive stance toward forms and structures of the standard dialect is enforced from the start of the schooling system. It is through this subtle insistence of just this one variety being acceptable that an ideology is established. Its mastery becomes a marker for the social and economic status and a gateway to success in other economic and social institutions (

Fairclough, 2010). SLI is also closely tied to attitudes about race and ethnicity and have the potential to act as the cover justification for discrimination against racial and ethnic those who use socially stigmatized varieties of English or languages other than English (

Barrett et al., 2023).

2. Language and Education

For students who speak a non-standard variety of English or otherwise do not conform to the expected language norms in educational settings, linguistic discrimination can cause alienation and hinder their academic success. As described by

Fillmore (

2004, n.p.), “[W]hat is it that differentiates students who make it from those who do not? This list is long, but very prominent among the factors is mastery of academic language.” While all students must learn SAE for purposes of academic writing when they begin attending school in the U.S., students who speak varieties aligned with SAE at home do not encounter as many differences in the academic register of SAE used at school. The issue of the development of conventions for standard academic English writing has been prominent, and as a result of that research, educational policies have been designed to address the needs of minoritized and first-generation university students, as well as students who have learned English as an additional language (e.g.,

Cummins, 2009;

Schleppegrell, 2004). However, considerably less attention has focused on the struggles that many other groups also routinely experience, including native and expert English speakers of regional or “non-standard” varieties of English, many of whom find academic language (“school English” in the words of

Charity Hudley & Mallinson (

2011)) to be new, difficult, and exclusionary. In both cases, students can experience negative bias, due to their communicative repertoires, which can preclude full participation in academic settings.

Research has shown that students who come to school using languages and linguistic varieties other than SAE do not have the same rate of success as students who do (

Kinzler et al., 2009;

Charity Hudley & Mallinson, 2011;

Murray, 2016;

Preece, 2015). The reasons for this include a lack of adaptation by administrators and teachers to bridge children’s home language and literacy practices with those of the classroom (

Heath, 2012) and instructors penalizing the use of home languages and varieties in school (

Fordham, 1998;

Talmy, 2010;

Wolfram et al., 1999). The differential rate of success for students who use nonstandard varieties of English or languages other than English at home extends to higher education as well. For example, in their study at a large research university,

Dunstan & Jaeger (

2015) interviewed students to determine their degree of use of stigmatized features of Appalachian English. They showed how those students who use these features describe their experiences at the university as being more peripheral than other students. They describe not speaking in class, not interacting with instructors and, in general, not feeling like a scholar. Another qualitative survey of students in higher education in the U.S. showed strategies that Latino students had for persistence in the science courses despite pervasive racial and linguistic discrimination (

Peralta et al., 2013). The study found that the academy does recognize the types of cultural capital valued in the Latino community. This includes the linguistic capital of being bilingual and the ability to interact in multiple languages outside of the standard academic English norm of the university.

High profile cases of discrimination against non-standard language varieties, especially those associated with Black Americans (Ann Arbor King case, Oakland Ebonics case:

Lippi-Green, 2012;

Smitherman, 1977) have raised awareness of this issue among language professionals, discrimination still occurs among educators in elementary and secondary education (

Bucholtz et al., 2018) and to date, has been largely unaddressed in higher education (

Wolf et al., 2018. But for exceptions see

Clements & Petray, 2021;

González et al., 2005;

Wolfram, 2023a). In fact, the kinds and degree of linguistic and dialect diversity of college students is not routinely tracked (

U.S. Department of Education, 2016).

While professional organizations such as the Conference on College Composition and Communication, the National Council of Teachers of English and the Linguistic Society of America have published statements affirming students’ rights to their own language varieties, in practice these ideals have not been systematically implemented at any level. “Unfortunately, language is one of those issues that remains unrecognized in the higher education diversity canon while it insidiously serves as an active agent for promoting inequality in campus life” (

Wolfram, 2023a, p. 37). The webpage of our own university’s Office of Global Diversity and Inclusion, for example, does not mention linguistic bias or discrimination, focusing instead only on discrimination based on federally protected classes. Furthermore, while language-related fields have acknowledged the validity and importance of supporting linguistic diversity, many academics outside these fields are untrained in language issues and are conflicted about how to handle non-standard language use in their classrooms (

Reichelt, 2021). Indeed, even faculty at institutions of higher education in the U.S., whose livelihoods depend on conforming to the conventions of SAE, may feel insecure about their ability to use this variety (

Wolfram & Dunstan, 2021). This insecurity is the result of the myths summarized above and discrimination that some linguistically and racially minoritized faculty have experienced (

Subtirelu, 2015;

Zhang-Wu, 2022). Consider the following reflections on the effect of the use of one’s own variety in these quotations from community members at our institution:

(1) “Speaking Appalachian English gives people a negative opinion of me before they know me… I feel like I have to preface every meeting with ‘I promise I am progressive’ in order to be liked at CLU”

(#1248, Graduate student)

(2) “In my experience, people from the Pacific Northwest negatively stereotype people who speak with a southern English accent or dialect. We are stereotyped as less smart and more politically conservative”

(#256, Faculty member)

(3) “I was the loud one so people don’t like that especially with accent. If I’m German or French that’s celebrated but because of my Japanese, Asian accent, not just my accent but because where the accent is coming from and how I look it’s just not fair”

(Int13, l. 371, Academic staff)

These examples illustrate how a bias against particular variations of English exist at our own institution. Regrettably, other research suggests this bias is pervasive at other institutions of higher education (

Tarantola, 2021;

Wolfram, 2023a). Given how central language is to teaching and learning at the university level, if ignorance about language variation and instances of language bias are left unaddressed, they will continue to perpetuate systemic inequalities and will continue to hinder the success of students who come to the university speaking a non- standard variety or speaking English as a second language. Several ironies present themselves: in a nation that prides itself on individualism, we proscribe ‘non-standard’ varieties of English (

Clements, 2021) and even at institutions of higher learning, people without scientific expertise in language or linguistics feel emboldened to claim that expertise when the issue is language (

Wolfram, 2023b).

As recent work at other institutions of higher learning has shown (

Wolfram, 2023a;

Wolfram & Dunstan, 2021), increasing awareness of exclusionary practices and discrimination based on language dialect use is needed.

Dunstan (

2013) found that university students who used a regional variety of English from Appalachia felt marginalized at their institution and that they needed to work harder than students who did not use this variety.

Wolfram & Dunstan (

2021) reported that a similar stigmatization was felt by university faculty members. Along with the stigmatization, they found attitudes that revalorized SAE as an ideal that students strive to achieve (

Woolard & Schieffelin, 1994).

3. The Project

The student population at our own institution has become increasingly more diverse with respect to race, ethnicity, and gender identity, and while Portland State University is designated a “majority-minority serving institution”, we noticed little attention being paid to diversity of languages and dialects found on campus over the years and developed a project designed to answer these questions:

Inspired by the work of

Wolfram & Dunstan (

2021), and supported by a small grant from our university, we began the multi-year project to describe the rich linguistic diversity on campus as well as community members’ attitudes toward their own and other community members’ linguistic repertoires with a goal of using our findings to systematically raise awareness of multilingualism and unspoken valuations of language on our own university campus. The Linguistic Diversity and Discrimination Awareness Project (LiDA) is an interdisciplinary, multiyear, mixed method research and dissemination project to raise awareness of language bias within the Portland State community and begin to develop institutional capacity to address language bias and discrimination campus wide. By documenting the level of linguistic and dialectal diversity and recording the experiences students, faculty, and staff regarding their language use we will be in the position to develop models of educational materials for different audiences that could be used for faculty/staff development, in student orientations or first year inquiry classes, and by the Office of Global Diversity and Inclusion (OGDI) as part of their ongoing training. To address these goals, this project consisted of three major components: A Linguistics Road Show, a campus-wide survey, and in-depth interviews and panel discussions. Below, we describe the project in detail to encourage similar projects at other institutions.

3.1. Linguistic Road Show

Starting in 2022, we have developed and presented activities and information via ‘Linguistic Road Show’ events. Staffed primarily by students, the Roadshow is a portable set of technologies and materials that can be easily set up in different spaces around campus. The technologies and materials (recording equipment, video displays, surveys) are used to raise awareness of basic concepts in linguistics, including attitudes towards languages and dialects. Activities include quiz games about interesting linguistic facts, real-time vowel description and mapping, and dialect attitude tests. Roadshow events also advertised the project’s survey (see next section) for community members who did not see the email solicitation.

3.2. Survey

We developed, piloted and distributed a 43-question language use survey via email to 24,351 members of the Portland State community and received an almost 10% response rate (2216) (It is important to mention for the numbers seen in the statistical analysis that more participants answered questions about languages spoken (2216) which came first in the survey, while fewer answered the questions about dialects and language bias experiences (1526). In future versions of the survey, we would reduce the number of total questions so that more participants would answer this question about dialect which came near the end of the survey). Questions asked community members about languages they spoke and in what contexts, what dialects of English they spoke, and whether they have experienced or witnessed discrimination based on their language use practices.

3.3. Interviews

Survey respondents were asked to contact us if they were interested in speaking more in a one-on-one interview. We have completed 55 interviews to date. Interviews asked participants about their language use practices at Portland State, their perceptions of language use practices on campus, and whether they perceive their own or others’ language use practices to be valued or devalued.

3.4. Panel Discussions

We have completed three moderated panel discussions at which various stakeholders (staff, faculty, administration, students) talked about their experiences with language in the education system and at Portland StatePortland State, specifically. In the panel discussion for faculty and staff, three of the five participants described themselves as bilingual and all expressed their opinion that faculty and staff at Portland StatePortland State need a greater awareness of the diversity of language and language varieties on campus. They also recognized that the institution itself could help in that effort through simple efforts such as recognizing and valuing students’ linguistic repertoires, using multilingual signage on campus and languages other than English on websites, and facilitating awareness raising workshops. We are in the process of analyzing two panel discussions for students and plan to hold a future panel as a live event before an audience on campus.

4. Preliminary Findings

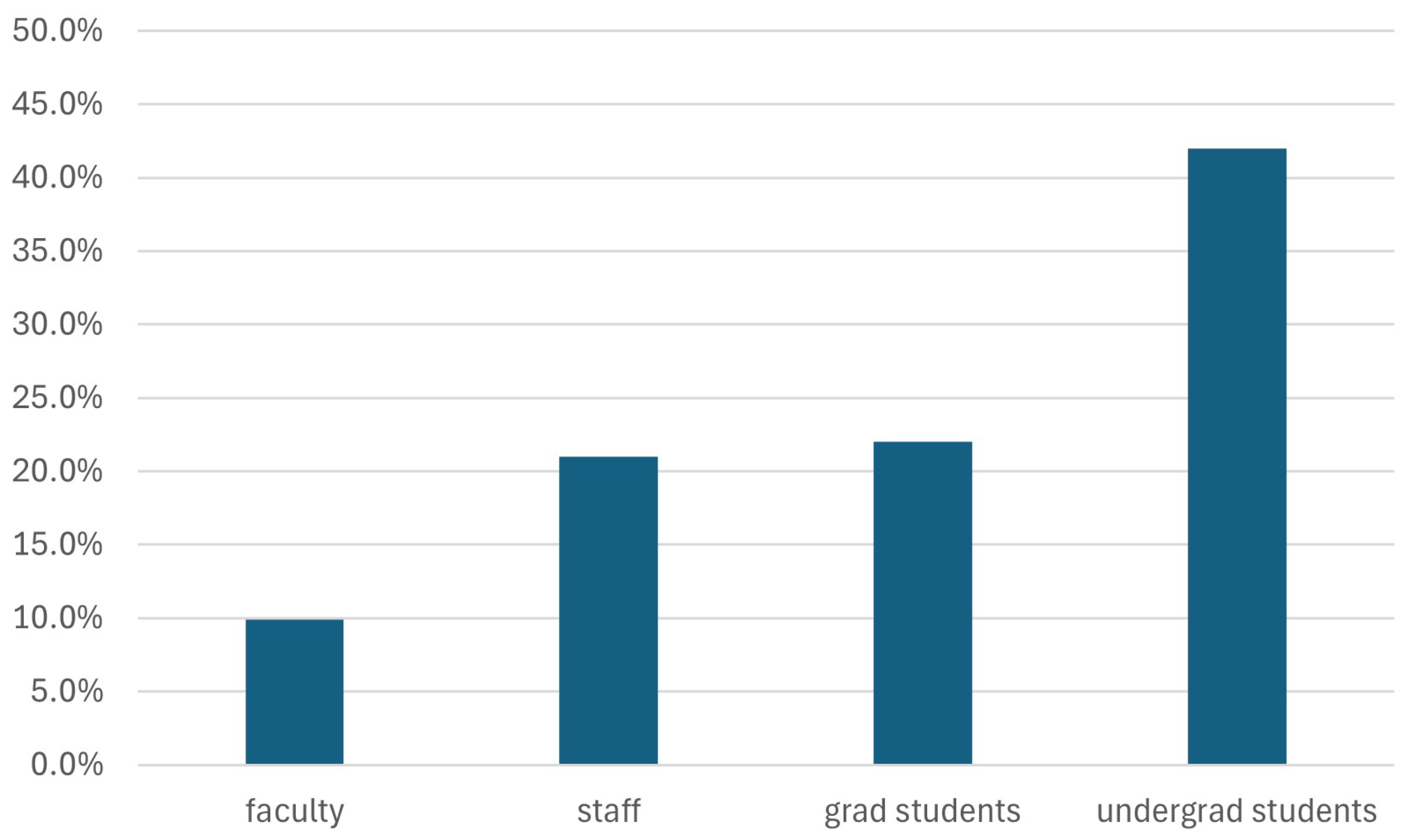

Survey responses reflect the proportion of responses by members of the different roles of the university (

Figure 1).

Languages used by survey respondents (other than English) were similar to the population of our metropolitan area: Spanish, Mandarin, Vietnamese and Russian with Japanese also highly represented due to the large numbers of students who study it formally at Portland State.

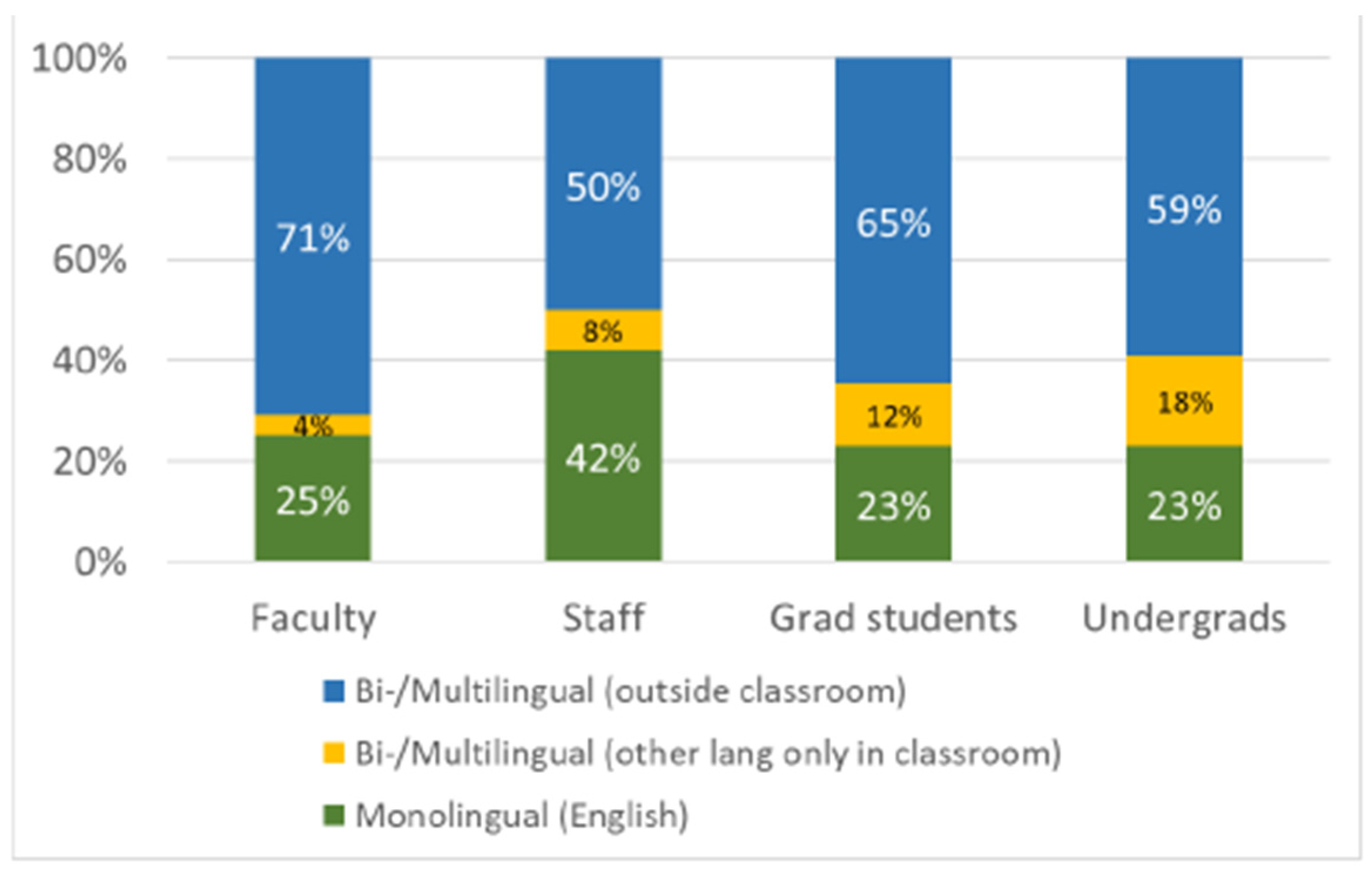

The survey shows us the level of multilingualism of the respondents (

Figure 2) with 71% of faculty, 65% of the grad students, 59% of the undergraduates, and 50% of staff indicating they use one or more languages outside the classroom in addition to English.

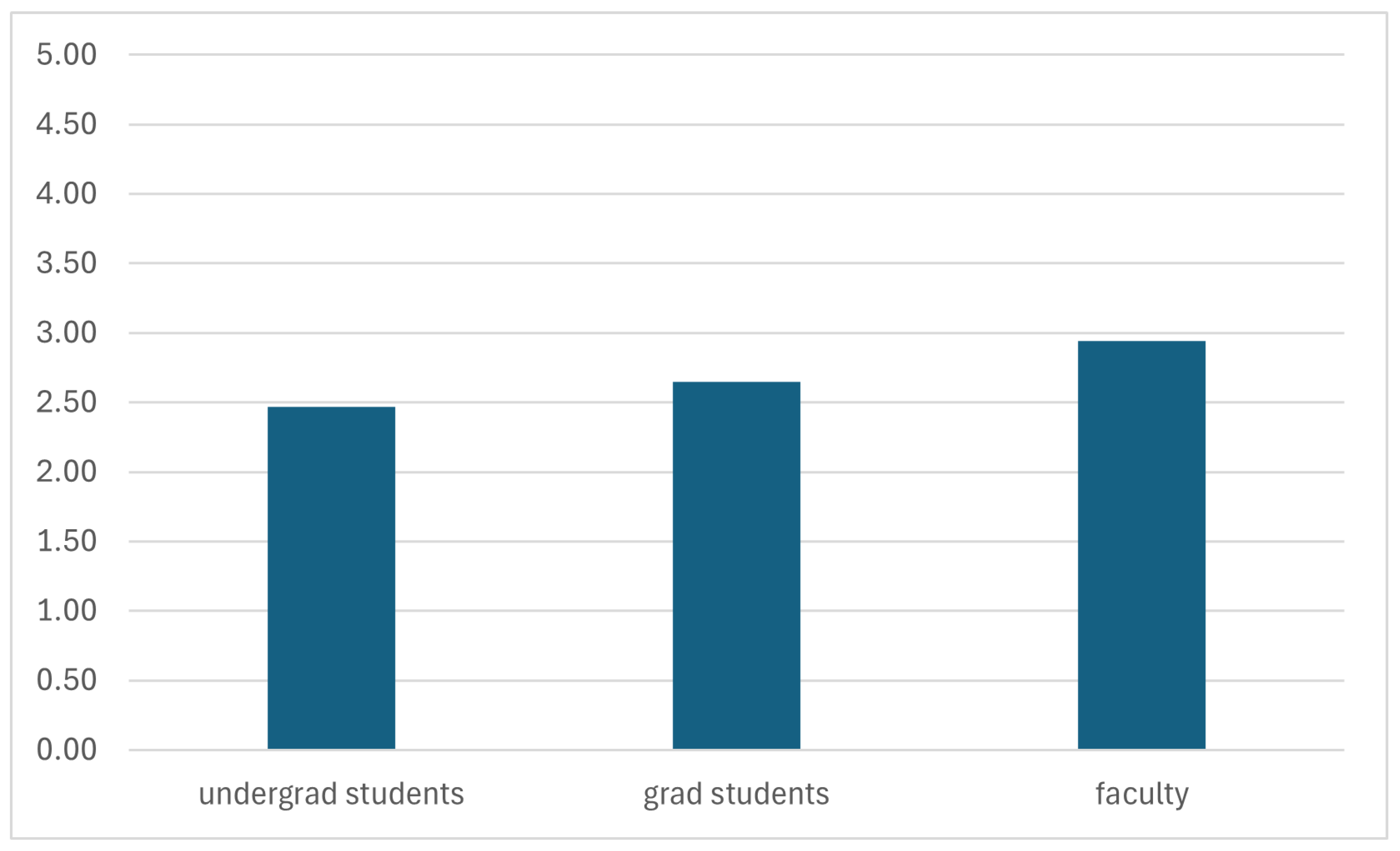

Despite the high level of multilingualism among student respondents, there is an understanding that sounding like a speaker of SAE is highly valued. In a five-point Likert scale response to the statement “I feel I will be equally successful at PSU if I speak standardized English or another dialect” with 1 being strongly disagree and 5 being strongly agree, the mean response for all participants was 3.70 (see

Figure 3).

A one-way ANOVA comparing the effect of role at the university on agreement with this statement revealed a statistically significant difference in the way different members of the PSU community responded to this question. (F(3,1407) = 3.966, p = 0.008. The post hoc LSD test found that the mean value for agreement with the statement was significantly different between faculty and undergraduate students (p < 0.001), 95% C.I. = [0.211, 0.713]) and graduate students (p = 0.043, 95% C.I. [0.006, 0.547]. Faculty responses demonstrated a statistically significant difference from student responses with faculty being more likely to agree (2.94/5) than students were (2.65/5 for graduate students; 2.47/5 for undergraduate students). This result suggests that students recognize the value of speaking the standardized variety and faculty may feel freer to use non-standardized varieties than students.

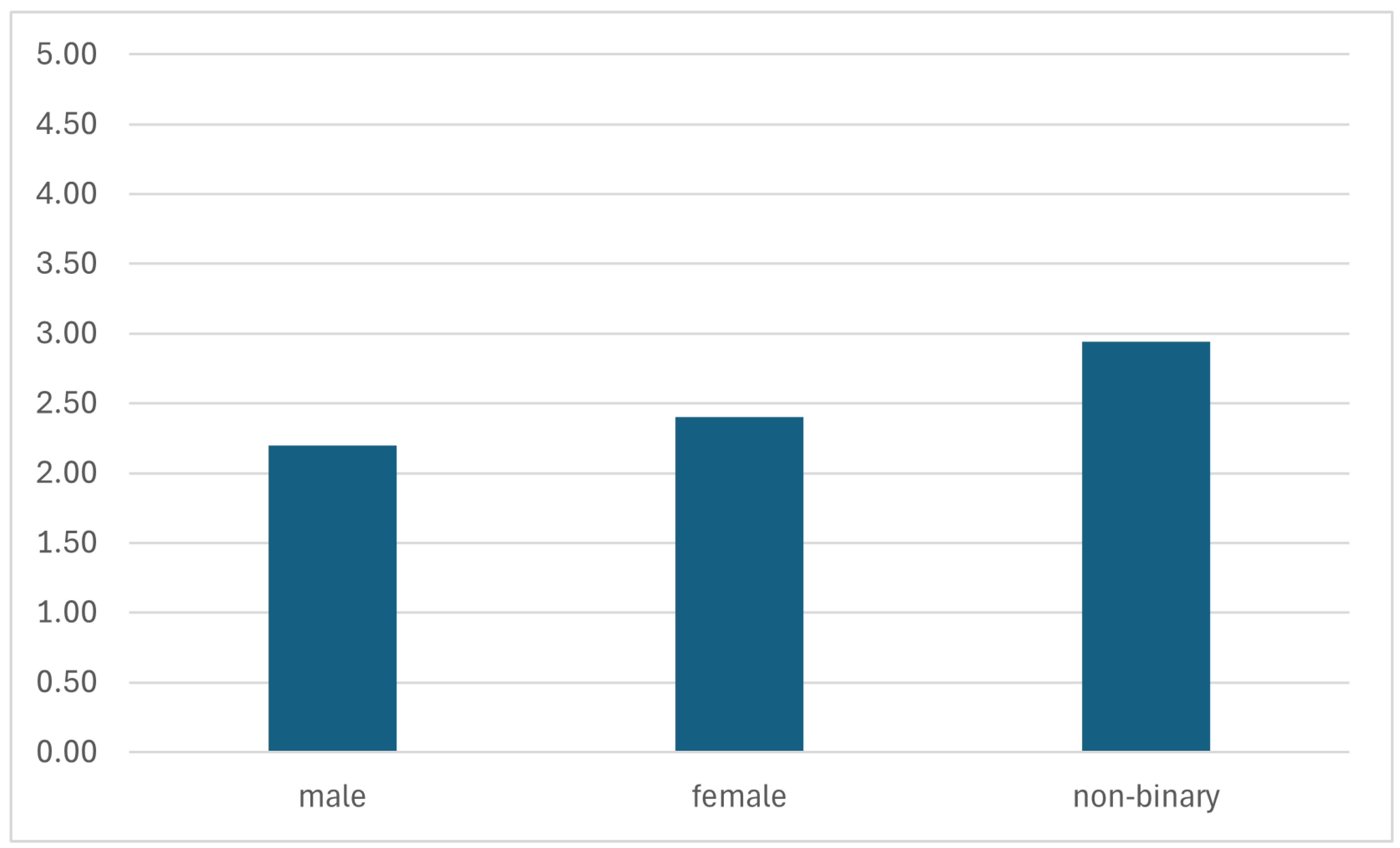

The intersection of language use and gender is seen in the response to the statement “I’ve felt pressure to adopt grammar/words that do not match my core identity at PSU”.

A one-way ANOVA comparing the effect of gender identification on agreement with this statement revealed a statistically significant difference in the way different gender identities responded to this question. (F(3,1478) = 7.46,

p < 0.001. The post hoc LSD test found that the mean value for agreement with the statement was significantly different between male participants and female participants (

p = 0.002, CI [−0.36, −0.08]), male participants and non-binary participants (

p < 0.001, CI [−0.70, −0.28]), and female participants and non-binary participants (

p = 0.005 CI [−0.46, −0.08]). Participants who identified as female were more likely than males to agree, and participants who identified as non-binary/gender queer were more likely than females and males to agree (see

Figure 4). The answers to this question show that the participants who are in the historically more marginalized groups feel less secure about the way they speak, and correspondingly, feel a greater need to modify their language use in order to fully participate in university education and social life.

4.1. Visibility

Our qualitative analysis of the interviews and focus group provides evidence for the need for greater awareness of the diversity of language and dialect use on campus as well as for instances of discrimination that have occurred. Faculty and staff with years of experience working at our university point to the symbolic violence (

Bourdieu, 1991) of a pervasive and hegemonic standard language ideology on campus (

Zhang-Wu, 2022). This occurs due to a lack of awareness regarding language varieties and the connection between language variation, standard language ideology, and learning. The following comments from faculty show that they understand SAE speakers’ frequent lack of awareness of language variation and the potential for discrimination that may arise out of such ignorance.

(4) “when I say [to members of my department] you do realize we have a certain rhetorical style in which we’re all expected to speak, people are stunned and they don’t want to acknowledge it. So I think if we acknowledge such differences in language exist, we can also understand it”

(31SC:242)

(5) “at our university languages other than English don’t really come up to be blunt…I don’t know that people know or care”

(11RB:232)

(6) “Until monolingual speakers can appreciate the significance of language difference as an aspect of our being, of how we think, of who we are, it’s going to be very difficult to even come up with pedagogical strategies”

(IE3YL:187)

(7) “Speaking SAE is something that I take for granted… the fact that that is something that I don’t have to put any mental real estate towards”

(6JB: 595)

One personal reflection about visibility from a library faculty member is important to consider with respect to the numbers of reported multilingual members of the community. In both an interview and focus group discussion, ‘Lisa’ noted the linguistic diversity among faculty and how that language expertise is not supported.

(8) “I wonder what the academy is reinforcing with our lack of non-English research materials and accommodation of different ideas. The academy starts looking awfully white and Western so that concerns me. I feel we’re giving the message that English is the only language that counts in academia”.

(IE1LA: 102)

4.2. Hegemony and Discrimination

We heard stories of students’ and faculty members’ use of home (non-standard) varieties of English not being valued and even ridiculed both at the university and in the workplace. These include comments like (9) & (10) from a staff member and alumni whose home dialect was not welcomed at our institution.

(9) “I was a monolingual first generation person coming from a very different class background entering into our university. I was very early and very clearly told that it was not okay to use non academic English. So it’s kind of a sink or swim environment that may be unspoken”

(IE2CF: 33)

(10) “I remember so clearly I had a paper where I wrote a sentence that was something along the lines of feeling poverty in my bones and my professor ripped that paper apart and told me that was a completely inappropriate way to approach an academic paper”

(IE2: 44)

Another staff member who came to the US as an international student (11) described the importance of language to one’s identity.

(11) “As a student, I had to unlearn how my Japanese brain worked to write a beautiful essay because otherwise I couldn’t pass. But language is the foundation of who we are …and just because the dominant culture says this is how we should write it’s like we are denied who we are”

(IEML:160)

A faculty member summarized (12) the value of Standard English and what those who do not use it face.

(12) “it’s kind of the currency for belonging and if you are not able to pay in that currency then then you sink and it’s okay for you to sink”

(IE3: 133)

The selected illustrative Quotations (4)–(12), illustrate the connection of language to identity and how attitudes toward SAE have an unseen regulatory effect. SAE is never overtly discussed as the best or only way to express oneself. Those who do not conform to the norms of SAE, however, may be corrected by faculty members or other institutional authorities in a private way. No one authority is cited as being politically incorrect or abusing power by prescribing SAE rules. Rather, the enforcement of SAE in higher education comes about from the continued lack of questioning of differential value for varieties of English. SAE is symbolically revalorized (

Woolard & Schieffelin, 1994), purported to be the neutral dialect, something understood by the general public. In this way, non dominant social groups can continue to be marginalized. not for their racial, ethnic, or gender identities, but rather, because they are not using recognized conventions for SAE.

We can see this primacy of SAE with some of the survey responses noting and even advocating for the use of SAE at the university.

(13) “I’m a white guy so maybe it isn’t my place to say this, but being graded on writing/speaking proper English is not racist and it is insane to think so”

(student)

(14) “I have seen only encouragement to speak “properly” in every academic setting I’ve encountered including PSU. If there is someone encouraging students to speak the dialect they are most comfortable with I have not heard them”

(student)

(15) “I would certainly hope that student grammar is being corrected on writing assignments. Certain “PSU settings”, such as formal writing, are not settings where one’s “core identity” should play a role”

(student)

(16) “Properly enunciated English makes for clearer communication and slang from English dialects can interfere”

(student)

5. Next Steps

As the analysis of survey, interview, and panel discussion data draws to a close, our next steps include a report to our Office of Global Diversity and Inclusion (OGDI) which will offer to work with OGDI to include information on linguistic diversity and linguistic bias as part of their resources and training materials. In collaboration with our office of Academic Innovation and our dean’s office, we will develop multimedia presentations and workshops for students, faculty, and staff that illustrate the linguistic diversity in the university community and portray multilingualism and multi-dialectalism as assets or resources for the university. The multimedia presentation will, in turn, become part of the Linguistics Road Show. These presentations will also be posted to a YouTube channel and our university’s media space to increase awareness and visibility of our efforts to address language bias and promote linguistic diversity. We will also develop a set of workshops aimed at faculty and TAs to be delivered in conjunction with our Office of Academic Innovation and include speakers of different languages and linguistic varieties. We are also beginning the process of expanding the project to local community colleges.

The establishment of LiDA has strengthened the mentoring of graduate and undergraduate students from historically underserved populations into the disciplinary community (

Charity Hudley, 2018), work that we started in several research groups since 2015 with the [name of group]. Although students continue to participate in the research group on a volunteer basis, we have seen the need to make the LiDA project a part of the undergraduate curriculum as we did with earlier projects on linguistic landscapes (

Hellermann et al., 2021). This coming academic year, one required course for undergraduate majors, a senior seminar, will be built around the project, reporting on the existing findings and implementing new rounds of data collection and analysis. First findings show the need for increased attention to linguistic diversity and cases of linguistic discrimination on our campus. But as part of an iterative process of integrating research and practice, we want to continue LiDA as a research-for-practice project to ensure that language-related policy at our university is informed by research. In the classes, we will develop new materials for the Linguistics Road Show which we then hope will become a regular component of events such as onboarding new faculty/staff, training TAs, a program at the university for incoming first-generation students, and other orientation events for students.

6. Conclusions

Our university is the most racially, ethnically, and linguistically diverse higher education institution in our state (

Powell, 2023). Our project has increased our university’s ability to achieve equity goals by making linguistic diversity on campus more visible and by demonstrating the need to acknowledge and value linguistic diversity. The work will allow the university to reimagine itself as a place for students whose language backgrounds include languages other than English and varieties of English beyond SAE and who may have previously felt like they did not belong in higher education. Additionally, this project increases our ability to achieve racial equity goals by unpacking the connections between language use, race, ethnicity, and social class, showing how when one stigmatizes a language or linguistic variety, this is often a proxy for discrimination based on (among other things) race or ethnicity (

Baugh, 2018;

Woolard & Schieffelin, 1994). Thus, the project addresses issues of systemic bias that affect students from different backgrounds and begins to develop a climate where linguistic diversity is supported and valued. This will, in turn, create a more welcoming discourse community on campus to attract students who formerly may not have felt part of a more traditional academic discourse community.

The project develops capacity and understanding at the institutional level for honoring the backgrounds of our increasingly diverse student body and addressing their specific linguistic experiences and needs. The work addresses the lack of visibility of traditionally stigmatized or undervalued languages and linguistic varieties in a university community in the 21st century. Many faculty, staff, and students are unaware of how students’ different linguistic backgrounds yield variable preparation for the use of academic English. Faculty may also not be aware of how different ascribed linguistic identities of students (e.g., non-native speaker, bilingual, speaker of Black English, speaker of rural English, speaker of Alabama English) potentially affect whether and how students participate in academic discourse. Our presentations and materials will provide resources for continued faculty development in this area and will inform curricula and policy to advocate for and celebrate linguistic diversity on campus.

We acknowledge that academic success currently requires students to use particular forms of language that include academic register, discipline-specific vocabulary, and traditional academic genres. Put more strongly, mastery of academic register language as well as discipline-specific terminology is catalytic of academic success (e.g.,

Halliday, 1993,

2004;

Hyland, 2012). For students whose multilingualism or multi-dialectalism is not valued, a sense of linguistic insecurity, a feeling that they do not belong, may prevent academic success. While the hegemony of SAE remains in place, greater awareness of the nature of multilingualism and language variation may help those of us in higher ed to help students unfamiliar with SAE to see that, given their linguistic background, they are well-prepared to learn another linguistic variety: Standard Academic English. A superordinate goal of the project is to empower students to align their academic and professional communication with expectations of academic language use (i.e., register, genre), while maintaining pride and confidence in their other language varieties.

Curricular changes arising out of research in linguistics and literacy have sought to address the hegemony of SAE in approaches to the assessment of academic writing that accepts the student’s unique language repertoire as a starting point. This translanguaging approach (

Canagarajah, 2011;

Hartse & Kubota, 2014) has not yet become widespread in the writing curriculum of higher education, including at our own university. Given the comments we have seen in our surveys and interviews, such an alternative approach to writing instruction and assessment would not only lead to better outcomes for current students but would be a recruitment tool for students who currently feel intimidated by their lack of experience with SAE.